Money for Nothing

by

P. G. Wodehouse

Literary and Cultural References

This is part of an ongoing effort by the members of the Blandings Yahoo! Group to document references, allusions, quotations, etc. in the works of P. G. Wodehouse.

Money for Nothing was originally annotated by Mark Hodson (aka The Efficient Baxter). Notes contributed by the late Terry Mordue are signed [AGOL] (A Gentleman of Leisure). The notes have been reformatted somewhat and have been significantly expanded and updated in 2020 by Neil Midkiff [NM] and others as credited below, but credit goes to Mark and Terry for their original efforts, even while we bear the blame for errors of fact or interpretation.

Money for Nothing first appeared as a serial, slightly abridged, in London Calling in 21 weekly installments from 3 March 1928 through 28 July 1928. In the US Liberty magazine, it appeared at nearly full length in fifteen weekly installments from 16 June 1928 through 22 September 1928.

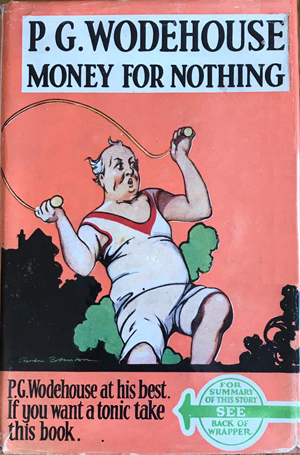

Money for Nothing was first published in book form by Herbert Jenkins in the UK on 27 July 1928 and by Doubleday, Doran in the US on 28 September 1928. The US first edition (as also its only apparent reprint, in 1929 by A. L. Burt from the Doubleday plates) differs from the UK text in having significant additional passages (totaling approximately 1,065 words), many of which are also present in the magazine serials, as well as a few small cuts and many word substitutions. Rather unusually, the US text generally uses UK spellings such as colour and neighbour, but there has been much editorial intervention (probably some done at each publishing house) in capitalization, punctuation, and the setting of compound words as two separate words, one hyphenated word, or one word without hyphens. These notes will include only significant rewordings and interpolated/omitted passages comparing the hardcover first editions, with occasional reference to the magazine serials, but not attempting to annotate all the passages omitted in those.

Mark Hodson’s original annotations relate to the Penguin (UK) reprint currently published, in which the text runs from page 1 to page 274. Newly interpolated notes are added in sequence and flagged with *; significantly updated notes are flagged with °. I [NM] do not have this recent edition; my slightly older Penguin reprints the Autograph Edition plates of 1959, even though its copyright page says “Published in Penguin Books 1991” as the current Penguin paperback also does. I have also not seen the earliest Penguin edition of 1964.

Neither the magazine serials nor the US book have chapter titles; only the UK book editions have chapter titles as given in the headings below.

|

Chapter 1 Chapter 2 Chapter 3 Chapter 4 Chapter 5 Chapter 6 Chapter 7 Chapter 8 |

Chapter 9 Chapter 10 Chapter 11 Chapter 12 Chapter 13 Chapter 14 Chapter 15 |

Money for Nothing (Ch. 0; page 0)

Money for Nothing was first published by Herbert Jenkins in the

UK on 27 July 1928 and by Doubleday, Doran in the US on 28 September 1928.

The book was written between June 1926 and July 1927. Norman Murphy has

worked out that Wodehouse started and finished it at Hunstanton Hall in

Norfolk, and worked in between times at London and Droitwich.

Dedication (Ch. 0; page 0) °

The Scottish writer Ian Hay (Captain Ian Hay Beith, 1876–1952) stayed

with Wodehouse at Rogate Lodge in Sussex in 1928, shortly before Money

for Nothing was published. He was working together with Wodehouse

on the dramatisation of A Damsel in Distress: they subsequently

went on a golfing holiday in Scotland together in Hay’s car.

Hay is perhaps best-known today for the early novel Pip (1907),

but between the wars he was also very successful as a dramatist and screenwriter.

The dedication does not appear in US editions.

Chapter 1 (Ch. 1; page 1)

Introducing a Young Man in Love

Runs from pp. 1 to 15 in the present Penguin edition.

Rudge-in-the-Vale (Ch. 1; page 1)

There is a village called Rudge, and a Rudge Hall, in Shropshire, not

far from Stableford, where Wodehouse’s parents lived for a while.

Of course, the name Rudge is also associated with the Rudge-Whitworth

motorcycle company (also based in the West Midlands) and Dickens’s

Barnaby Rudge. Perhaps the similarity of sound between Carmody

and Barnaby suggested the name?

Jubilee Watering Trough (Ch. 1; page 1) °

In rural districts, a frequent way to commemorate Queen Victoria’s jubilee in 1897 was to erect a watering trough for the benefit of local horses, thus offering them some refreshment while their owners were in the pub. Many small villages in Wodehouse have one.

You can find these in Maiden Eggesford (“Tried in the Furnace,” 1935, and Aunts Aren’t Gentlemen, 1974); Walsingford Parva (Summer Moonshine, 1938); and Steeple Bumpleigh (Joy in the Morning, 1946).

a little group of serious thinkers *

Compare “Comrade Bingo”:

…in front of me there stood a little group of serious thinkers with a banner labelled “Heralds Of The Red Dawn”…

and “The Long Arm of Looney Coote”:

Everybody seemed to be fighting everybody else, and at the back of the hall a group of serious thinkers, in whom I seemed to recognize the denizens of Biscuit Row, had begun to dismember the chairs and throw them at random.

Broadway, Piccadilly, Rue de Rivoli (Ch. 1; page 1)

Famously busy streets in New York, London and Paris, respectively.

grey stone of Gloucestershire... (Ch. 1; page 1)

This, and other evidence later in the book, suggests that the geographical location Wodehouse was thinking of was Droitwich, the small Worcestershire Spa town where part of Money For Nothing was written.

Skirme (Ch. 1; page 1)

Skirme is a surname that occurs occasionally in England, but neither Skirme

nor any of its obvious variants seems to be an existing British placename

or river.

The river at Droitwich is called the Salwarpe.

and lets the world go by (Ch. 1; page 1)

Diego Seguí finds a possible source in the poem “Sunshine” by Robert W. Service (appealing, because PGW quotes Service elsewhere).

Norman church (Ch. 1; page 1)

Like that of Market Blandings, the church dates from the period of roughly a hundred years (1066–1154) which followed the Norman conquest of England. Characteristics of the Norman style of church architecture include: round-headed arches and doorways, the latter often a series of concentric, stepped-backed arches, each with its own columns, and with the doorway head often infilled with a carved tympanum; thick walls, often buttressed; the use of simple barrel or tunnel vaulting in crypts, but rarely in naves, because of the weight and outward thrust on the walls; massive columns with a plain capital, later examples being thinner and with a carved capital. [AGOL]

eleven public-houses (Ch. 1; page 1)

The implausible number of pubs to be found in small English towns is a

running joke in Wodehouse. Again, Market Blandings is singularly well-provided

in this respect.

The reason for the existence of all these pubs is normally that the town

has a weekly market serving a large and prosperous agricultural district,

with a population much bigger than that of the town itself. Farmers attending

the market would need somewhere to eat, drink, and negotiate business;

traders coming from further afield to buy or sell would need to stay overnight.

Automobile Guide (Ch. 1; page 1)

The Automobile Association and the Royal Automobile Club both published guidebooks for their members with details of hotels, garages, and other local information for every town in Britain.

Chas. Bywater, Chemist (Ch. 1; page 1) °

Chas. is a conventional abbreviation for Charles. Wodehouse is quoting

his name as it would appear on the shop sign — another running joke.

He seems to be the only Bywater in the canon, although there are a number

of Attwaters in Wodehouse.

A “Chemist” in Britain is usually a pharmacist who also sells

toiletries and the like: something like a drugstore in the US. (As noted in section II, p. 6, Bywater’s inventory is even more inclusive and varied than most chemists’.)

live wire *

From the original meaning of a wire carrying electricity, the colloquial meaning of an energetic, lively, talented person arose in the US at the end of the nineteenth century. The first use so far found in Wodehouse:

It was about time that Uncle Cooley had a real live-wire looking after the Pulp and Paper Company’s affairs.

Bill the Conqueror, ch. 2 (1924)

Cf. Jno. Banks, hairdresser, the sole live wire in Market Blandings in Leave It to Psmith (1923).

Colonel Meredith Wyvern (Ch. 1; page 2) °

Meredith is a traditional Welsh man’s name (originally Maredudd

or Meredydd). For obscure reasons, Americans seem in recent years to have taken to using

it for girls. A Wyvern is a heraldic creature — a winged

dragon with an eagle’s legs and a serpent’s tail.

Colonel Aubrey Wyvern and his daughter Jill appear in Ring for Jeeves/The

Return of Jeeves (1953).

Brophy’s Paramount Elixir *

Brophy is a characteristic Irish surname, not used by Wodehouse for any of his onstage characters. Paramount as an adjective means superlative, of highest rank or quality; compare Duff and Trotter’s Paramount Ham in Quick Service (1940). Wodehouse usually uses “elixir” in its generic (and originally alchemical) sense of a liquid with transformative power, when referring to the seemingly magical effects of good alcoholic beverages. This is his only use so far found in the name of a pharmaceutical remedy.

the reign of Queen Elizabeth (Ch. 1; page 2)

This is Elizabeth I, who reigned from 1558–1603, of course. The future Elizabeth II was still wearing nappies when this was written.

a wobbly menace *

The US magazine serial has the form “wabbly” here; see A Damsel in Distress.

as near as a toucher *

British colloquial for “as close as possible without actually touching (or, figuratively, taking place).”

set fire to the train (Ch. 1; page 2)

When blasting with gunpowder, it was the usual practice to lay a “train” of powder along the ground to ignite the main body of the explosive with a suitable time delay. This involved many hazards, especially when working out of doors; with dynamite, one would be more likely to use a detonator with electric ignition.

nobility and gentry *

In the British aristocracy as of the time of writing of this book, “nobility” refers to peers of the ranks of duke, marquess, earl, viscount, or baron, and members of their immediate families who bear courtesy titles or honorifics. “Gentry” refers to non-titled members of their families; to those of the lower ranks of baronet, knight, and dame; and to those bearing formally recognized coats of arms as landowning families from feudal times.

glass going up *

That is, increasing barometric pressure, typically associated with pleasant weather.

thug *

Originally a term (capitalized) for a class of professional stranglers in India; transferred in the late nineteenth century to apply to violent criminals and ruffians in general.

Mr. Lester Carmody (Ch. 1; page 3) °

Carmody is an Irish surname, particularly associated with County

Clare. Mr. Carmody and his nephew Hugo are the only characters of that name

listed in Garrison.

Lester as a first name is more common in the US than in Britain:

it seems to be related to the placename Leicester. There are a few other

Lesters in the canon, e.g. Lester Mapledurham in “Strychnine in the

Soup”; Lester Burdett in Barmy in Wonderland/Angel Cake; Lester Burrowes in The Adventures of Sally; and J. Lester Clam in the Playboy revision of “The Right Approach”.

he stood there with his ears flapping, waiting for details *

The OED’s first citation for “ears flapping” in the sense of “listening attentively” is from Wodehouse:

But, as a matter of fact, it was the work of a moment with me to chuck away my cigarette, swear a bit, leap about ten yards, dive into a bush that stood near the library window, and stand there with my ears flapping.

“Jeeves Takes Charge” (1923)

jelly-bellied *

Probably used in the literal sense of “soft in the abdomen”; Mr. Carmody is a fat man, weighing 220 pounds. But a figurative meaning of “cowardly, not firm in having ‘guts’ ” is also possible. No connection, of course, with the Jelly Belly brand of candies, introduced in 1976.

suing him (Ch. 1; page 5)

Probably the Colonel would have a better case against the men doing the blasting (or Mr. Carmody in his capacity as their employer) for not securing the area properly before setting off the charges. The House of Lords is the highest court of appeal in England and Wales; Wyvern would only have been able to take his case so far if he could get a senior judge to certify that it involved an important new point of law. Juries were still involved in most types of civil action when this was written — nowadays they are only used in defamation cases.

Blackhander (Ch. 1; page 5)

Presumably a reference to Ujedinjenje ili Smrt (Union or Death), also known as the Black Hand, which was a secret terrorist organisation formed in Serbia in 1911 to further the cause of Pan-Serbianism in territories then forming part of the Austrian Empire, especially Bosnia and Herzegovina. They infiltrated Serbian nationalist organisations and were most famously responsible for the assassination of Archduke Franz-Ferdinand in Sarajevo on 28 June 1914.

picking oakum (Ch. 1; page 5)

Oakum is loose fibre obtained by unpicking ropes, and formerly used for

caulking the seams of ships. Picking oakum was a tedious and unpleasant

type of work commonly given to prisoners in the 19th century.

Prison sentences are awarded only in criminal cases. If he wanted to see

Carmody behind bars, Wyvern would have to try to persuade the police (nowadays

it would be the Crown Prosecution Service) to bring a prosecution for

battery.

lint *

A soft wound-dressing material consisting of fibers of flax, made from scraping or shredding linen rags.

arnica (Ch. 1; page 6)

A tincture made from the dried flower heads of the plant Arnica montana is often used to relieve pain when treating minor wounds.

half-crown (Ch. 1; page 6)

See Uncle Dynamite.

Sooth-o *

See Hot Water for other patent medicines whose names end in “-o” as coined by Wodehouse.

Abhik Majumdar suggests that the name is reminiscent of Sugg’s Soothine in Full Moon, which is of course a specific for gnat bites, so is hence a direct competitor to Brophy’s Paramount Elixir (above) rather than Sooth-o, which is recommended more for “cuts, burns, scratches, nettle-stings and dog-bites.”

believed in Preparedness *

The earliest Google Books citations of this phrase in general discussion of military readiness date from 1916. That same year, Wodehouse and Jerome Kern wrote a song titled “Polly Believed in Preparedness” for the musical Have a Heart; the lyric references the Boy Scout motto “Be prepared.” At this distance of time, it is unknown whether the song was the literary source for, or a reaction to, the use of “believed in preparedness” in news and political discussions.

Old Rugbeian (Ch. 1; page 6) °

The grammar school at Rugby in the East Midlands was established by a

London grocer, Lawrence Sheriff, in 1567. It rose to prominence in the

nineteenth century under Thomas Arnold (headmaster 1828–1842; the father

of Matthew Arnold). His educational and organisatory ideas, widely copied

by other schools and publicised in Thomas Hughes’s novel Tom

Brown’s Schooldays, established the notion of ‘Public Schools’

as the key institutions of the English class system: if you had been to

one, you were a gentleman; if not, the best you could hope for was to

send your son to one.

Rugby School is also famous as the birthplace of Wodehouse’s favourite

sport, of course.

The Old Rugbeian tie has broad stripes of navy and green and a narrow stripe of white. (Clicking the link opens a new window with an image from the Rugby school shop.)

Marshall Field (Ch. 1; page 6) °

Marshall Field (1834–1906) started out as a shop assistant, and in 1851

established the Chicago shop which became Marshall Field & Co., the

largest and most famous retail store of its day. The company was taken

over by Target Corporation in 1990, but department stores under the Marshall Field

name still existed in most midwestern cities when Mark Hodson first prepared these notes in 2003. The company was acquired by Federated Department Stores, Inc., in 2005 and the stores were renamed Macy’s in 2006.

(As an aside: his grandson, Marshall Field III (1893–1956), later a successful

newspaper proprietor, would have been at Eton and Cambridge at the same

time as many of Wodehouse’s young men.)

crystal sets (Ch. 1; page 6)

Crystal radio receivers used a ‘cat’s whisker’ diode (a thin wire forming a Schottky contact with a selenium crystal) to separate the signal from the carrier wave. They did not have any amplification, so they could be very cheap and simple, and did not need a battery or mains electricity; the disadvantage was that you could only listen with headphones, and discrimination between stations was poor.

pipe-joy *

Wodehouse named a fictional dog biscuit Donaldson’s Dog-Joy; this is the only use of “pipe-joy” so far found in his works.

her nose edged against the door *

Thus in both US and UK original book editions, but the US serialization Liberty has wedged here; the UK magazine serial omits the sentence.

Robot (Ch. 1; page 6)

The word was invented by Karel Capek (1890–1938) for his play R.U.R.

(‘Rossum’s Universal Robots’) (1920), translated into

English in 1923. Capek also wrote a book called ‘The War of the Newts’

that gave offence to Gussie Fink-Nottle.

like the note of the Last Trump (Ch. 1; page 6)

Behold, I tell you a mystery: We all shall not sleep, but

we shall all be changed,

in a moment, in the twinkling of an eye, at the last trump: for the

trumpet shall sound, and the dead shall be raised incorruptible, and

we shall be changed.

For this corruptible must put on incorruption, and this mortal must

put on immortality.

But when this corruptible shall have put on incorruption, and this mortal

shall have put on immortality, then shall come to pass the saying that

is written, Death is swallowed up in victory.

Bible: 1 Corinthians 15:51–54; see Biblia Wodehousiana.

Lincoln Hotel, Curzon Street (Ch. 1; page 11)

Curzon Street is in Mayfair (not far from the Drones Club). At present, the only hotel in the street is the Curzon Plaza. There is a Lincoln House Hotel in Marylebone.

a daughter in the post office *

The original independent telegraph companies in the UK were nationalized in 1870 and run by the General Post Office, so postal employees would be able to know the content of telegraphed messages such as this. There is no need to suspect them of opening private letters in this case.

who for some years now had looked after the business of the estate for his uncle *

This phrase is omitted in the US edition, perhaps deemed redundant with the fuller discussion of dairy-farm expenses in chapter V, section iii.

the Dex-Mayo (Ch. 1; page 12)

Seems to be fictitious, but many car makers had hyphenated names of this sort (Rolls-Royce, Mercedes-Benz, Hispano-Suiza, etc.): Mayo is a county in the West of Ireland, of course, so presumably this is meant to be an Irish make of luxury car.

Le Touquet (Ch. 1; page 13) °

Le Touquet–Paris Plage is a seaside resort in northern France, about 15 km south of Boulogne. Still very fashionable in the twenties, although it declined in popularity with the upper classes when they started going to the Riviera in summer as well as winter.

Plum and Ethel Wodehouse stayed there in the mid-1930s, first in hotels, later renting a house called Low Wood, which they bought in 1935. This is where they were living when the Germans invaded France and took Plum as an enemy alien to an internment camp in 1940.

a Puck-like look *

See Shakespeare Quotations and Allusions in Wodehouse.

slight tip-tiltedness *

See A Damsel in Distress.

Doctor Crippen (Ch. 1; page 13)

Peter Hawley Harvey Crippen (1862–1910), an employee of an American patent medicine company (technically his US diploma didn’t entitle him to call himself ‘doctor’ in Britain) poisoned his wife Cora, a music hall singer, in February 1910 and buried her dismembered body in the cellar of their house in Camden Town. When the police became suspicious he fled to Canada with his mistress, Ethel Le Neve. They were spotted and arrested at sea amid huge publicity, thanks to radio telegrams sent by the captain of the ship.

Brides-in-the-bath murderer (Ch. 1; page 13)

Another celebrated murder case of the period: George Joseph Smith (1872–1915) killed three successive wives between 1912 and 1915 by drowning them in the bath. As in the Crippen case, evidence from the forensic pathologist Sir Bernard Spillsbury was crucial in the case against him.

The scales seemed to have fallen from his eyes *

See Biblia Wodehousiana.

Chapter 2 (Ch. 2; page 16)

Healthward Ho

Runs from pp. 16 to 31 in the present Penguin edition.

The US edition breaks this chapter into two sections, i and ii; the UK text has an undivided chapter.

Healthward Ho (Ch. 2; page 16) °

The name of Dr. Twist’s establishment is obviously a reference to Westward Ho!, the only novel by Charles Kingsley to have had a Devon seaside resort named after it. (Surely “Water Babies” would have been a better choice?)

Graveney Court (Ch. 2; page 16)

Graveney is a small village in the marshes of North Kent. Murphy suggests (see also p.68 below) that Healthward Ho/Graveney Court is based on Wodehouse’s grandmother’s house Ham Hill, so perhaps there is an association of ‘ham’ and ‘gravy’ at work here?

New Men for Old (Ch. 2; page 16)

In the story “Aladdin and the enchanted lamp,” one of the standard plots for traditional British pantomime (although it now seems that this ‘traditional Arabian story’ was most probably invented by the French orientalist Antoine Galland in the early 18th century), Aladdin’s wicked uncle deceitfully offers him “new lamps for old.” Dr. Twist is being labelled as a dodgy character.

Mens Sana in Corpore Sano (Ch. 2; page 16)

Latin: a healthy mind in a healthy body (Juvenal).

Formerly a saying frequently used when persuading people of the virtues

of exercise: it has dropped out of favour, presumably because we now value

healthy bodies much more highly than sound minds.

“out of shape” *

Doctor Twist puts the phrase in quotation marks because it is a fairly recent coinage, and an American one at that. The oldest OED citation (in their “Draft additions” section for the word shape) for “out of shape” in the sense of not being in good physical condition is from 1933.

does itself too well when the gong goes *

In large British country houses, a gong was rung by the butler to alert all the household and guests that dinner was ready, and often also a short time in advance (“dressing gong”) to remind people to put on their evening clothes. More modest establishments would have a “dinner bell” instead. Wodehouse is hinting that the sort of customers who would need and could afford his course of treatment probably lived in large houses and indulged themselves freely at elaborate multiple-course dinners.

a better liver *

Popular opinion on medical matters often concentrated on the liver as the seat of health, not only in digestive senses but more generally (“feeling liverish” or “a chill on the liver”). Given its role in processing and storing fats and metabolizing alcohol, Dr. Twist’s patients would not have been too far wrong in attributing at least some of their symptoms of excessive intake to that organ.

ex-Sergeant-Major Flannery (Ch. 2; page 18) °

The Sergeant-Major is the senior warrant officer in an army regiment, who assists the Adjutant and is responsible for matters including the training of recruits. Before the days of specialist sports teachers, retired NCOs were often employed in schools as Physical Training instructors.

Other Wodehouse characters with the same surname:

G. J. Flannery, a literary agent, appears in Bachelors Anonymous.

Otto Flannery, formerly a Hollywood agent, now runs The Happy Prawn and is married to Ivor Llewellyn’s third wife Gloria in Pearls, Girls and Monty Bodkin.

Flannery and Martin own a Sloane Square book shop in The Girl in Blue.

Any of these may or may not be the same as the Flannery that Howard

Saxby Senior keeps mentioning in Cocktail Time, who may be his stockbroker or may be entirely imaginary.

Sherlock Holmes … could have told … *

Wodehouse’s initial readers would have thought of Holmes in contemporary terms; the last of the short stories, “The Adventure of Shoscombe Old Place” was published in magazines in March and April of 1927, and it may not have been clear that the series had concluded. Indeed, in chapter 9 of this book, he is spoken of in the present tense: “Sherlock Holmes can extract a clue from a wisp of straw or a flake of cigar ash.”

Julius Cæsar ... about him (Ch. 2; page 18)

Let me have men about me that are fat;

Sleek-headed men, and such as sleep o’ nights:

Yond Cassius has a lean and hungry look;

He thinks too much: such men are dangerous.

Shakespeare, William (1564–1616): Julius Caesar I,ii

See Shakespeare Quotations and Allusions in Wodehouse for more references to this passage.

Thirty guineas a week… *

See Ukridge for the background of using guineas for professional fees. A guinea was equal to 21 shillings (one pound and one shilling), so the weekly fee would be £31/10/- or 630 shillings. (The equivalent purchasing power in 2020 would be on the order of £2,000 or $2,500 US.) This does indeed work out to 90 shillings or £4/10 per day, three shillings and ninepence per hour (3.75 shillings, and there are twelve pence in a shilling) which works out to 45 pence. A farthing is one-fourth of a penny, so three farthings per minute is an exact calculation. Whatever mental gymnastics it may take for modern readers accustomed to decimal coinage to assimilate these older units, they at least had the advantage of being evenly divisible by factors of two, three, four, five, six, and (for amounts in guineas) seven.

salver *

See Leave It to Psmith.

a lissom young man *

This is our first view of Hugo Carmody, who returns in Fish Preferred/Summer Lightning (1929) and Heavy Weather (1933), and is remembered in Pigs Have Wings (1952).

features of a markedly simian cast *

The US and UK magazine serials and US book omit this phrase.

cold shower *

See A Damsel in Distress.

“Turkish this side, Virginian that.” *

Pongo Twistleton’s cigarette case in Uncle Dynamite, ch. 8.1 (1948) and Judson Phipps’s in “Life with Freddie” (1966, in Plum Pie) both contain the same choice of tobacco sources. Turkish tobacco is sun-cured and was known for being milder and aromatic; former brands such as Murad and Fatima were exclusively Turkish. It is now more expensive, and appears as one component in blended brands such as Camel. Virginia tobacco is heat-cured and grown from varieties developed in the nineteenth century which could grow in less-fertile soils; its stronger yet sweeter flavor became increasingly popular in Europe and the USA in the early twentieth century.

gasper *

See Right Ho, Jeeves.

“it’s no life for a refined Nordic.” *

The US magazine serial and the UK book have “Nordic” here; the UK magazine and US book read “Caucasian” instead. Compare:

…the thunder, lightning and rain which so often come in the course of an English summer to remind the island race that they are hardy Nordics and must not be allowed to get their fibre all sapped by eternal sunshine like the less favoured dwellers in more southerly climes.

Summer Lightning, ch. 12.1 (1929)

The OED cites this sentence from the UK book as an example in its definition of Nordic as a noun.

triturated sawdust (Ch. 2; page 21)

To triturate something is to grind it down to a fine powder or chew it, which seems somewhat redundant in the case of sawdust. Trituration has a special significance in homeopathy, where it is used to “dynamise” substances before dissolving them.

coffin-nail *

Originally US slang for a cigarette; OED citations go back to 1888 and include the present sentence from Wodehouse. The antiquity of the popular term gives the lie to claims that the dangers of cigarettes were not known until the mid-twentieth century. US magazine and book read “coffin nail” without hyphen.

bulldog breed *

Describing the courage and tenacity of what was considered the ideal British character; the “John Bull” personification of an Englishman has often been depicted accompanied by a bulldog.

There has always been something of the good old English bulldog breed about Bingo.

“The Metropolitan Touch” (1922)

Theoretically, no doubt… *

The US book begins section ii of Chapter Two at this point.

that Kruschen feeling (Ch. 2; page 21)

“He’s got that Kruschen feeling” — advertising slogan for Kruschen salts (a proprietary laxative) ca. 1924.

The US magazine serial in Liberty substitutes that good-will-to-all-men feeling here; probably an allusion to Luke 2:14:

Glory to God in the highest, and on earth peace, good will toward men.

sweetness and light *

See Sam the Sudden, and be sure to follow the further link there.

a gallon of petrol *

That would be an imperial gallon, just a little more than 1.2 US gallons, 4.54609 liters.

one shilling and sixpence halfpenny *

Decimalized, about £0.077; in modern purchasing power, roughly five pounds.

bring home the bacon *

See Laughing Gas.

the School-Girl Complexion *

“Keep that schoolgirl complexion” was a long-running slogan of Palmolive soap from 1917 on, praised by advertising experts early on and referred to as “that schoolgirl complexion look” in ads into the middle 1950s.

a noise like a buffalo pulling its foot out of a swamp *

Ambrose, about to follow, was halted by a noise like a buffalo taking its foot out of a swamp, and perceived that his employer, Mr. Llewellyn, wished to have speech with him.

The Luck of the Bodkins, ch. 6 (1935)

I should have expected something that sounded more like a buffalo pulling its foot out of a swamp.

Laughing Gas, ch. 16 (1936)

There are two things I particularly dislike about G. D’Arcy Cheesewright—one, his habit of saying ‘Ho!’, the other his tendency, when moved, to make a sound like a buffalo pulling its foot out of a swamp.

Jeeves and the Feudal Spirit, ch. 3 (1954)

He found speech, if you could call making a noise like a buffalo taking its foot out of a swamp finding speech.

Kipper Herring, in Jeeves in the Offing/How Right You Are, Jeeves, ch. 13 (1960)

His only reply was a sound like a hippopotamus taking its foot out of the mud on a river bank…

Stiff Upper Lip, Jeeves, ch. 24 (1963)

The newcomer’s only response was a bronchial sound such as might have been produced by an elephant taking its foot out of a swamp in a teak forest.

“Sleepy Time” (1965; in Plum Pie)

She uttered a sound rather like an elephant taking its foot out of a mud hole in a Burmese teak forest.

Aunts Aren’t Gentlemen, ch. 10 (1974)

the milk of human kindness *

See Shakespeare Quotations and Allusions in Wodehouse.

put his fortune to the test, to win or lose it all *

See The Girl on the Boat.

“His name’s Fish.” *

In the US book and UK magazine serial, Hugo continues this speech by adding “Ronnie Fish.”

Bond Street (Ch. 2; page 26)

Running between Oxford Street and Piccadilly, Bond Street is home to many of London’s most expensive shops. The name of the street commemorates Sir Thomas Bond, a courtier and property developer who was part of a consortium that acquired the former site of Clarendon House in the late 17th century to build Old Bond Street. Nowadays London’s nightlife is centered a little further east, around Piccadilly Circus/Leicester Square and in Soho.

looney-bin *

The lunatic asylum. See Leave It to Psmith for earlier uses and two other spellings.

Quarrel scene from Julius Caesar (Ch. 2; page 27)

The famous quarrel between Brutus and Cassius forms the first part of

Act IV, Sc. 3 of Shakespeare’s play.

http://www.bartleby.com/70/4043.html

Smokers (Ch. 2; page 27)

A smoking concert was an informal entertainment for the members of a men’s club (or as here, the undergraduates of a college). Normally the members of the club would take it in turns to get up and perform. As there were no ladies present, smoking was permitted.

Mr. Carmody said he did. *

In US and UK magazine serials and US book, this sentence is worded more actively:

“I do,” said Mr. Carmody.

Albert Hall (Ch. 2; page 27)

The construction of this concert and meeting hall in South Kensington

in 1867 was one of the public projects undertaken with funds raised by

the Great Exhibition of 1851. It is a large, circular building, topped

by a shallow dome.

http://www.royalalberthall.com/

Eustace Rodd ... Cyril Warburton (Ch. 2; page 27) °

Both seem to be fictitious. There are no major characters in the canon called Rodd or Warburton, although there are plenty of Todds and there is Lady Anne Warblington in Something Fresh. A Colonel Warburton encourages the Wambledon tennis players with sudden, sharp hunting noises in “Prospects for Wambledon” (1929, collected in Louder and Funnier).

Welter-weight (Ch. 2; page 27) °

Welter-weight boxers have a weight between that of a light-weight and

a middle-weight. At this period, before the weight classes were more finely divided in the mid-twentieth century, a welter-weight weighed over 147 lb. (66.68 kg) but not over 160 lb. (72.57 kg).

Wodehouse had a keen interest in both professional and amateur boxing.

One of his first trips to America was timed to allow him to see an important

fight, and boxing plays an important part in several of his early books

(cf. e.g. The Pothunters, Not George Washington, Psmith

Journalist)

the heavyweight champion of the world is actually named Eugene *

Hugo is mistaken here; “Gene” Tunney (heavyweight champion 1926–28) was actually named James Joseph Tunney (1897–1978). He retired undefeated in 1928.

Boat Race night (Ch. 2; page 27) °

The Oxford and Cambridge boat race takes place on a four and a half mile course on the Thames (between Mortlake and Putney), on a Saturday during the Easter vacation. It was first held in 1829. As it is in the vacation, it used to be an occasion for large numbers of students to gather and celebrate in London. See The Code of the Woosters for additional detail and more Wodehouse references.

at the eleventh hour *

See Biblia Wodehousiana.

“getting along and taking your shower, Mr. Carmody” *

For unknown reasons the US book has “showers” here.

“I hope … you aren’t sore at me for calling you down about those student’s lamps.” *

Thanks to Green’s Dictionary of Slang for pointing us to what must be Wodehouse’s source for this obscure bit of US slang for cigarettes, from one of Plum’s favorite American authors, George Ade, in In Babel, 1903.

stepped on the self-starter *

See Bill the Conqueror.

marts of trade *

A fancy way of referring to retail business:

“It is only to be expected that at a bazaar in aid of a deserving cause the prices of the various articles on sale will be in excess of those charged in the ordinary marts of trade.”

“Buttercup Day” (1925)

Tubby, it was plain, had struck it rich and come a long way since the old Criterion days when he used to plead with her to chalk the price of his modest refreshment up on the slate, explaining that credit was the life-blood of Commerce, without which the marts of trade could have no elasticity.

Pigs Have Wings, ch. 7 (1952)

Sunday, with the marts of trade closed and no chance of going out and doing a little shopping, was always a dullish day for Dolly Molloy…

Ice in the Bedroom, ch. 9 (1961)

Hugo Carmody, the Square Dealer *

See If I Were You.

carolled like a linnet in the springtime *

See the two adjacent notes on linnets for Summer Moonshine.

Chapter 3 (Ch. 3; page 32)

Hugo Does His Day’s Good Deed

Runs from pp. 32 to 36 in the present Penguin edition.

“Yes sir ... that’s my baby” (Ch. 3; page 32)

Song by Gus Kahn and Walter Donaldson. Seems to have first been a hit for Blossom Seeley in 1925: later recorded by many others, of course.

“without a taint of vulgarity or suggestiveness” *

“In my opinion, good clean fun, gratifyingly free from all this modern suggestiveness.”

Hot Water, ch. 2.1 (1932)

“It’s the duty of all of us in these licentious post-war days to put our hands to the plough and quench the flame of this rising tide of unwholesome suggestiveness.”

“The Code of the Mulliners” (1935)

He was genuinely grateful to his recent buddy for having given him five minutes of clean, wholesome entertainment, free from all this modern suggestiveness, and he wished him luck if he was planning to sell that ring to Beefy.

Cocktail Time, ch. 8 (1958)

Hugo, in a similar situation, would have advertised his love like the hero of a musical comedy… *

But there’s no reticence about Bingo. He always reminds me of the hero of a musical comedy who takes the centre of the stage, gathers the boys round him in a circle, and tells them all about his love at the top of his voice.

“Scoring Off Jeeves” (1922)

To hear his aspirations put into bald words like this made him feel as if he were being divested of most of his more important garments in a crowded thoroughfare. *

Listening to “Parted Ways” made him, personally, feel as if he had suddenly lost his trousers while strolling along Piccadilly.

“Best Seller” (1930, collected in Mulliner Nights)

Widgeon Seven *

See Summer Moonshine.

Blenheim Park (Ch. 3; page 35)

Country estate at Woodstock, about ten miles north of Oxford, given to the first Duke of Marlborough in recognition of his services as a general, or possibly in gratitude for his wife’s friendship to Queen Anne. The Palace (not visible from the road) was designed by Sir John Vanbrugh.

Martyrs’ Memorial (Ch. 3; page 35)

A Victorian obelisk in St. Giles (the continuation of the Woodstock Road into the centre of Oxford), designed by Sir Giles Gilbert Scott, and erected in 1842. It commemorates the three bishops (Cranmer in 1556, Latimer and Ridley in 1555) whom Queen Mary burnt at the stake nearby in Broad Street.

Clarendon Hotel (Ch. 3; page 35)

This ancient coaching inn (known as the Star before it was rebuilt with a new facade in 1743) stood in Cornmarket, a little way south of the Martyrs’ Memorial. It was demolished in a fit of civic vandalism in 1954, to be replaced by a Littlewood’s department store (now in turn replaced by a miniature shopping mall called the Clarendon Centre).

dickey (Ch. 3; page 35) °

In this context, a folding extra seat on the back of a car, usually using the lid of the luggage compartment. Equivalent to the US “rumble seat.”

Chapter 4 (Ch. 4; page 37)

Disturbing Occurrences at a Night Club

Runs from pp. 37 to 65 in the present Penguin edition.

picking a winkle out of its shell *

An edible gastropod (marine snail), in full periwinkle; a mollusk of genius Littorina.

the Portuguese, the Argentines and the Greeks (Ch. 4; page 37) °

Refrain of a mildly ethnocentric comic song by Arthur M. Swanstrom and Carey Morgan, published 1920. In the song, these three nationalities are represented as taking over everything from subway seats to American patriotism.

And a funny thing — when we start to sing

“My country ’tis of thee”

None know the words but the Portuguese,

the Argentines and the Greeks.

Arthur M. Swanstrom & Carey Morgan: The Argentines, the Portuguese and the Greeks

The sheet music is online:

http://scriptorium.lib.duke.edu/sheetmusic/a/a02/a0232/a0232-2-72dpi.html

Wodehouse wrote the introduction to a book by Charles Graves titled —And the Greeks (London: 1930, Geoffrey Bles; New York: 1931, Robert M. McBride) whose title derives from this song.

She extended her hand composedly. *

The UK magazine serial and US book have two additional sentences completing this paragraph:

In her this meeting after long separation had apparently stirred no depths. Her demeanour was friendly, but matter-of-fact.

The US magazine serial includes only the second of these sentences.

as if he was something unpleasant that had come to light in a portion of salad *

Compare:

…he had kept silkworms as a child, and there had been the deuce of a lot of fuss and unpleasantness over them. Getting into the salad and what-not.

Indiscretions of Archie, ch. 7 (1921)

Mr. Llewellyn did not speak, merely looked at Monty as if he had been a beetle in the salad…

The Luck of the Bodkins, ch. 21 (1935)

Other similar references in Wodehouse usually specify a caterpillar, often in the salad of a vegetarian:

Mr. Downing—for it was no less a celebrity—started, as one who perceives a loathly caterpillar in his salad.

Mike, ch. 36 (1909) (“The Lost Lambs”, ch. 7, 1908)

He put up his eyeglass, and stared at the offending journal with the air of a vegetarian who has found a caterpillar in his salad.

The Prince and Betty [US edition], ch. 14 (1912)

It was with the sullen repulsion of a vegetarian who finds a caterpillar in his salad that he now sat glaring at them.

Something New, ch. 1 (1915)

He lugged them out of the drawer as if he were a vegetarian fishing a caterpillar out of the salad.

Jeeves and the purple socks, in “Jeeves and the Chump Cyril” (1918; as “A Letter of Introduction” in The Inimitable Jeeves, 1923)

Nothing, of course, in this world is perfect; and, rosy as were the glasses through which Archie looked on his new surroundings, he had to admit that there was one flaw, one fly in the ointment, one individual caterpillar in the salad.

Indiscretions of Archie, ch. 4 (1921)

But there is always a fly in the ointment, a caterpillar in the salad.

“The Clicking of Cuthbert” (1921)

She stared at him wildly, as she might have stared at a caterpillar in her salad.

“Jane Gets Off the Fairway” (1924)

“Yes,” said Millicent, rather in the tone of voice which Schopenhauer would have used when announcing the discovery of a caterpillar in his salad.

Summer Lightning, ch. 11.3 (1929)

And now she was wearing a look of definite disapproval, like a duchess who has found half a caterpillar in the castle salad.

“The Knightly Quest of Mervyn” (1933; in Mulliner Nights)

She had lowered her knife and fork, and was staring at her plate with a sort of queenly disgust, like Mrs. Siddons inspecting a caterpillar in her salad.

Quick Service, ch. 1 (1940)

He eyed me for a moment as if I had been a caterpillar in some salad of which he was about to partake, and resumed.

Joy in the Morning, ch. 19 (1946)

She gave him a fleeting look, the sort of look a good woman gives a caterpillar on finding it in her salad, and turned back to Gally.

Pigs Have Wings, ch. 4.3 (1952)

It was a cold, disapproving gaze, such as a fastidious luncher who was not fond of caterpillars might have directed at one which he had discovered in his portion of salad, and I knew that the clash of wills for which I had been bracing myself was about to raise its ugly head.

Jeeves and the Feudal Spirit, ch. 1 (1954)

Giving this snail-impersonator a look such as a particularly fastidious princess might have given the caterpillar which she had discovered in her salad, Jane averted her gaze, and was continuing to avert it, when the uncouth intruder spoke.

Something Fishy/The Butler Did It, ch. 10 (1957)

She was looking cold and revolted, like a princess who has discovered a caterpillar in her salad.

“Unpleasantness at Kozy Kot” (1958, in A Few Quick Ones [US edition, 1959])

Where Lady Constance had winced at the sight of Lord Emsworth like a Greek goddess finding a caterpillar in her salad, she smiled upon him as if their meeting were something to which she had been looking forward for years.

A Pelican at Blandings, ch. 1.2 (1969)

He lowered the beaker as I drew near and regarded me in a squiggle-eyed manner like a fastidious luncher observing a caterpillar in his salad.

Aunts Aren’t Gentlemen, ch. 16 (1974)

Cleopatra (Ch. 4; page 41)

Cleopatra VII (69–31 BCE), Macedonian queen of Egypt, the last of the Ptolemies to hold power. As head of the most economically important country in the region, she inevitably became involved in the power struggles for the control of the Roman Empire, marrying Julius Caesar and, after Caesar’s assassination, Mark Anthony (she also had to marry two of her younger brothers and one of her sons at various times to comply with Egyptian dynastic law). When Anthony was defeated by Octavian she committed suicide rather than be humiliated as a Roman captive.

Catherine of Russia (Ch. 4; page 41)

Catherine the Great (1729–1796). German-born princess who overthrew her husband, Peter III, in 1762 to become empress of Russia. During her reign, industries were built up, Russia’s military power consolidated, and the construction of St. Petersburg completed. Russia was exposed to strong cultural influences from the European enlightenment, but none of them seem to have done anything to improve the lot of the peasants, who only suffered from more efficient government control of their lives.

the Laughing Cavalier (Ch. 4; page 43)

The modern name for a portrait by the Haarlem painter Frans Hals (ca.1580–1666), showing a cheerful — if not exactly lissom — young man with a fine upswept moustache and goatee beard. The painting is now in the Wallace Collection in London.

“Mitt … my dear old friend” *

Mitt is US slang for greeting with a handshake, cited in the OED from 1908 onward; probably a jocular combination of “meet” with “mitten” as slang for the hand.

Thomas G. Molloy (Ch. 4; page 43) °

The Molloys and their associate “Chimp” Twist first appeared in Sam the Sudden, three years earlier. In that novel, Soapy took Dolly’s maiden surname for his own alias, pretending to be Thomas G. Gunn, father of Dora “Dolly” Gunn. This is their second outing.

Founder of the Feast *

Reminiscent of Bob Cratchit’s toast to Mr. Scrooge in A Christmas Carol by Charles Dickens.

Ben Baermann’s Collegiate Buddies (Ch. 4; page 45) °

Wodehouse seems to have been fond of popular songs (quite apart from writing

their lyrics himself!), but evidently disliked club musicians: this is by no means

the only place where a nightclub band gets a raw deal from him. Presumably,

in calling the band “collegiate buddies” he wants the reader

to conclude that they are neither.

In his liner notes for his recording of the Kern–Wodehouse–Bolton musical

Sitting Pretty, conductor John McGlinn quotes Kern on this subject,

“None of our music now reaches the public as we wrote it except in

the theatre. It is so distorted by jazz orchestras as to be almost unrecognizable.[...]

A composer should be able to protect his score just as an author does

his manuscripts.[...] The public, through the cabaret and radio broadcasting,

is not getting genuine music, only a fraudulent imitation.”

Kern in fact banned the score of Sitting Pretty (1924) from being

broadcast or recorded by dance bands. Wodehouse would surely have been

aware of his partner’s feelings on this subject and presumably agreed

with him. [Ian Michaud/The Mixer]

the same spirit of captious criticism… *

See Sam the Sudden.

Lot ... cities of the plain (Ch. 4; page 45)

In the book of Genesis, Lot is Abraham’s nephew. He goes to live

in the cities of Sodom and Gomorrah in the Jordanian plain. In Gen. 19,

a couple of angels turn up and tell him to take his family and flee, as

the cities are due to be demolished, without a UN mandate, for unspecified

wickedness. (Christian theologians have since had a lot of fun inventing

evil acts that the Sodomites might have been guilty of, had they thought

of them.)

However, there isn’t any specific reference in the text to Lot himself

regarding the cities in a spirit of captious criticism.

See Fr. Rob’s take on this at Biblia Wodehousiana.

The Courtship of Miles Standish (Ch. 4; page 46) °

Miles Standish (ca.1584–1656) was one of the members of the group of colonists

who travelled to America on the Mayflower in 1620. He had been

a professional soldier, and became the military leader and treasurer of

the Plymouth colony.

Longfellow’s blank-verse epic of 1858 seems to have little or no

historical foundation. Standish, a shy widower, sends his beautiful young

secretary, John Alden, to court Priscilla the Puritan Maiden on his behalf.

Although Pat remembers the words, she has got the plot mixed up: Alden

is secretly in love with Priscilla himself, as she quickly realizes, so

she is chiding him for carrying another’s message, not (as Pat thinks)

for relying on a messenger.

Longfellow seems to be critical of Standish not for lacking the courage

to carry his own proposal, but for thoughtlessly putting his friend Alden

in an impossible position.

Thereupon answered the youth:—“Indeed I do not condemn

you;

Stouter hearts than a woman’s have quailed in this terrible

winter.

Yours is tender and trusting, and needs a stronger to lean on;

So I have come to you now, with an offer and proffer of marriage

Made by a good man and true, Miles Standish the Captain of Plymouth!”

Thus he delivered his message, the dexterous writer of letters,—

Did not embellish the theme, nor array it in beautiful phrases,

But came straight to the point, and blurted it out like a schoolboy;

Even the Captain himself could hardly have said it more bluntly.

Mute with amazement and sorrow, Priscilla the Puritan maiden

Looked into Alden’s face, her eyes dilated with wonder,

Feeling his words like a blow, that stunned her and rendered her speechless;

Till at length she exclaimed, interrupting the ominous silence:

“If the great Captain of Plymouth is so very eager to wed me,

Why does he not come himself, and take the trouble to woo me?

If I am not worth the wooing, I surely am not worth the winning!”

Then John Alden began explaining and smoothing the matter,

Making it worse as he went, by saying the Captain was busy,—

Had no time for such things;—such things! the words grating harshly

Fell on the ear of Priscilla; and swift as a flash she made answer:

“Has he no time for such things, as you call it, before he is married,

Would he be likely to find it, or make it, after the wedding?”

…

But as he warmed and glowed, in his simple and eloquent language,

Quite forgetful of self, and full of the praise of his rival,

Archly the maiden smiled, and, with eyes over-running with laughter,

Said, in a tremulous voice, “Why don’t you speak for yourself, John?”

Henry Wadsworth Longfellow: The Courtship of Miles Standish, III

“My Sweetie is a Wow” (Ch. 4; page 47) °

Mark Hodson didn’t find a song with this exact title: he thought it could perhaps be a mixed-up reference to the opening lines of the song “If You Knew Susie” (1925). Despite what Meyer and DeSylva suggest, Shakespeare seems to be innocent of the expression “...is a wow” — the OED records it as 1920s slang, with one of the first examples being from The Small Bachelor.

I have got a sweetie known as Susie

In the words of Shakespeare she’s a “wow”

Though all of you may know her, too

I’d like to shout right now…

B. G. DeSylva & Joseph Meyer: If You Knew Susie

[Note an earlier PGW usage of “is a wow” in Bill the Conqueror from 1924, before this song was published, so the slang phrase itself predated the song. Linking it to “sweetie” may well have been influenced by the song, though the title as quoted here may be a Wodehouse invention, since the only references Google can find are to this story. —NM]

jellyfish ... mind of your own (Ch. 4; page 47)

A jellyfish does have a mind of its own, if not a very highly developed

one. Its nervous system is distributed throughout the body, and there

is no central brain.

Usually, jellyfish in Wodehouse are used to stand for spinelessness, a

quality they indubitably have to excess.

you’ve gone blah (Ch. 4; page 47)

Dull, unadventurous (slang). The OED seems to have missed this one — it records the first use in print as Ngaio Marsh in 1937. (Blah as a noun, used to describe meaningless talk, is also from the 1920s.)

“Our Miss Wyvern appears to have got the wires crossed.” *

See Hot Water.

Keats ... forlorn (Ch. 4; page 49)

Wodehouse seems to have thought Keats wrote knell, not bell. He also uses “the very word is like a knell,” mentioning Keats, in the concert scene of The Girl on the Boat.

... The same that oft-times hath

Charmed magic casements, opening on the foam

Of perilous seas, in faery lands forlorn.

Forlorn! the very word is like a bell

To toll me back back from thee to my sole self!

John Keats: Ode to a Nightingale, 68–72

it simply isn’t on the board *

See Ice in the Bedroom.

Jewish black beetle (Ch. 4; page 50)

Wodehouse experts have never been able to work out how Jewish black beetles are to be distinguished from coleoptera of other faiths, although there have been some ingenious suggestions. Wodehouse didn’t often descend to this sort of cheap and inexact insult: obviously he considered nightclub musicians were not worth the price of a fully-thought-out Wodehouse insult.

Ronald Overbury Fish (Ch. 4; page 51) °

This is his first appearance: he returns in Summer Lightning and Heavy

Weather, with a mention of his marriage in The Luck of the Bodkins. Fish is not an uncommon name, but there must be at least a suspicion

that Wodehouse chose the name so that people could call him “that

poor Fish.”

The village of Overbury, just south of Bredon Hill in Worcestershire,

is close to Hanley Castle and Malvern, where Wodehouse had relatives and

spent time in his youth.

Sir Thomas Overbury (1581–1613) was a poet and courtier of James I, who

died of poisoning while imprisoned in the Tower of London after upsetting

the royal favourite Robert Carr and the influential Howard family.

Eton (Ch. 4; page 51)

Eton College is the oldest public school in England. It was founded in 1440 by King Henry VI as “The King’s College of Our Lady of Eton beside Windsor.” A year later, the king founded King’s College, Cambridge, with the intention that scholars from Eton would continue their education there.

Trinity College, Cambridge (Ch. 4; page 51)

Established in 1546 by Henry VIII. Probably has more famous alumni than the rest of Oxford and Cambridge universities put together. Ronnie and Hugo, assuming they were up in the early 1920s, might have encountered Hardy and Ramanujan, Alfred Whitehead, Lord Rayleigh, Wittgenstein, A. E. Housman, and many other great names.

“Shall I like your uncle?”

“No.” *

US and UK magazine and US book texts have a longer version of the second line:

“No,” said Hugo confidently.

She reminded him of a leopardess, an animal of which he had never been fond. *

US magazine and US book texts omit this sentence. UK magazine omits the entire paragraph.

“Oh?” said John. *

US magazine and book continue this paragraph with:

He supposed the practice of calling a father by a nickname in preference to the more old-fashioned style of address was the latest fad of the Modern Girl.

In the US magazine, “modern girl” is in lower case.

marcelled hair *

Vine Street (Ch. 4; page 56) °

Vine Street is a small side street between Piccadilly and Regent Street, close to Piccadilly Circus. It was the site of a police station, now closed, the headquarters of “C” Division of the Metropolitan Police.

Wodehouse disguises it slightly as “Vinton Street” in Jeeves and the Feudal Spirit (1954).

after hours (Ch. 4; page 56) °

Until quite recently, English licensing laws didn’t make any separate provision for nightclubs, which were (theoretically) supposed to stop serving alcohol at 11 p.m., like pubs.

US magazine serial and book have “after prohibited hours” here.

All quiet along the Potomac (Ch. 4; page 57)

Popular song of the American Civil War. The Potomac is the river which flows through Washington, DC.

“All quiet along the Potomac,” they say,

Except now and then a stray picket

Is shot as he walks on his beat to and fro

By a rifleman hid in the thicket.

’Tis nothing. A private or two now and then

Will not count in the news of the battle;

Not an officer lost. Only one of the men

Moaning out all alone the death rattle.

All quiet along the Potomac tonight,

Where the soldiers lie peacefully dreaming,

Their tents in the rays of the clear autumn moon,

O’er the light of the watch fires, are gleaming;

There’s only the sound of the lone sentry’s tread

As he tramps from the rock to the fountain,

And thinks of the two in the low trundle bed,

Far away in the cot on the mountain.

His musket falls slack, and his face, dark and grim,

Grows gentle with memories tender,

As he mutters a prayer for the children asleep,

For their mother, may Heaven defend her.

The moon seems to shine just as brightly as then

That night when the love yet unspoken

Leaped up to his lips when low-murmured vows

Were pledged to be ever unbroken.

Then drawing his sleeve roughly over his eyes,

He dashes off tears that are welling,

And gathers his gun closer up to its place

As if to keep down the heart-swelling.

He passes the fountain, the blasted pine tree,

The footstep is lagging and weary;

Yet onward he goes, through the broad belt of light,

Toward the shades of the forest so dreary—

Hark! Was it the night wind that rustled the leaves?

Was it moonlight so wondrously flashing?

It looks like a rifle—“Ah! Mary, good-bye!”

And the lifeblood is ebbing and splashing.

All quiet along the Potomac tonight,

No sound save the rush of the river;

While soft falls the dew on the face of the dead—

The picket’s off duty forever.

Ethelinda Beers (1827–1879): All Quiet Along the Potomac

more or less jake *

US slang for “satisfactory, excellent, fine” dating from 1914; the OED cites Wodehouse’s use in Bill the Conqueror (ch. 6.2 of the book, ch. 8.2 of the magazine serial linked here).

a keen east wind *

In the UK, east winds have traveled over a large Continental land mass, and in winter can be very cold.

a bad quarter of an hour *

A direct translation of the French idiomatic phrase un mauvais quart d’heure, also common in its English version since the middle of the nineteenth century.

A very deep depression off the coast of Iceland … Snow Queen *

More metaphors for the coldness of Pat’s manner as she feels that she has been neglected during the police raid. The first is more meteorological talk; the second is a reference to an 1844 fairy tale by Hans Christian Andersen.

Hell hath no fury like a woman scorned *

See Right Ho, Jeeves.

He likes to nuzzle them. *

The verb has a variety of meanings, some relating to the nose (as a horse might affectionately push its nose up against a person it likes), and some less specifically physical, for cherishing and coddling something, “to provide with a snug place of rest” [OED]. The US book has the misprint “muzzle” here.

An American statistician … nearly fifty different methods of replying in the affirmative *

This appears to be a quotation from Pathfinder, v. 33, p. 16 (1926). Google Books gives only a snippet view, but the “found inside” text says:

Louis Pound, of the University of Nebraska, there are too many substitutes for the word “yes” in the English language. ... The list includes: yeth, yap, yum, yo, yaws, yezz, chess, chass, chahss, chuss, ’es, yair, chow, yip, yaw, yap, yop, yup, yurp, ...

Pots of money. *

See Ukridge.

a twin set of head phones *

As mentioned above, crystal radio receivers did not have amplification so as to be able to drive loudspeakers, so must be listened to with headphones. The picture of husband and wife enjoying the same radio broadcast together is a charming one.

Just a Real Good Face. *

US magazine serial and book omit this sentence.

I suppose I’ve sold more dud oil stock to suckers” *

The US and UK magazine and US book have “bum oil stock”—but the Jenkins editors apparently thought the colloquial UK sense of “bum” as “posterior” necessitated a change for their readers.

“You don’t say!”

“Yes, ma’am!”

“Well, isn’t that great. Is he rich?” *

In US and UK magazines and US book, the second and third lines are:

“I do say!”

“Well, isn’t that the greatest thing. Is he rich?”

US magazine also has an exclamation point after “thing” here.

stately homes of England *

See Leave It to Psmith.

the bulls after us *

US slang for the police; Chapman (New Dictionary of American Slang) says it is from the 1700s.

something attempted, something done… *

Something attempted, something done,

Has earned a night’s repose.

Longfellow: “The Village Blacksmith”

Chapter 5 (Ch. 5; page 66)

Money for Nothing

Runs from pp. 66 to 88 in the present Penguin edition.

compelled to gaze every time they looked out of window *

The UK first edition reads as above; later UK editions (Autograph 1959 and following) and US and UK magazine serials have “out of the window”; the US first edition book reads “out of windows” here.

The older British idiom “out of window” is also found in Summer Lightning, ch. 12.1:

“What have you been doing, Mr. Baxter?”

“Jumping out of window.”

…disappointed with Rudge. *

US and UK magazine serials and US book have a paragraph break following this, and insert:

There are times in everyone’s experience when Life, after running merrily for a while through pleasant places, seems suddenly to strike a dull and depressing patch of road: and this is what was happening now to Pat. The sense, which had come to her so strongly in the lobby of the Lincoln Hotel in Curzon Street, of being in a world unworthy of her—a world cold and unsympathetic and full of an inferior grade of human being, had deepened.

The new paragraph (or two paragraphs in US magazine, with slightly different punctuation) continues with “Her home-coming…” as in UK book.

The phrase “pleasant places” may allude to Psalm 16:6: “The lines are fallen unto me in pleasant places; yea, I have a goodly heritage.”

piazza (Ch. 5; page 67)

In this context, the inner courtyard of a town house (Shakespeare does not use this Italian word).

Capulets ... Montague (Ch. 5; page 67) °

In Shakespeare’s Romeo and Juliet, these are the two feuding families in Verona. Juliet is the daughter of Lord Capulet, and Romeo is a Montague, of course.

US and UK magazines and US book continue the paragraph with:

And, though, being a modern girl, she did not as a rule respond with any great alacrity to parental mandates, she had her share of clan loyalty and realized that she must conform to the rules of the game.

deadline (Ch. 5; page 67)

This is the original meaning of deadline: a line (usually the perimeter of a prison) which may not be crossed on pain of death. The meaning time limit, used in the publishing industry, came in around 1920.

Lowick (Ch. 5; page 68)

Fictitious: obviously a reference to Powick, where Wodehouse’s grandmother lived. It is about twenty miles from Droitwich, the main source for Rudge.

Pat, still distrait *

The adjective, meaning “distracted from attention, absent-minded,” is a borrowing from French. The editor of the US book treated it as a foreign word and used the French feminine form “distraite” here.

diablerie (Ch. 5; page 70)

Devilry, mischief.

life in the old dog yet *

US and UK magazines and US book have considerably more material in this and following paragraphs. The easiest way to show this is to present the passage as in the US book, with material omitted in the UK book in red.

The Dolly whom Colonel Wyvern beheld was a beautiful woman with just that hint of diablerie in her bearing which makes elderly widowers feel that there is life in the old dog yet. Colonel Wyvern was no longer the dashing Hussar who in the ’nineties had made his presence felt in many a dim sitting-out place and in many a punt beneath the willows of the Thames, but there still lingered in him a trace of the old barrack-room fire. Drawing himself up, he automatically twirled his moustache. To Colonel Wyvern Dolly represented Beauty.

To Chas. Bywater, with his more practical and worldly outlook, she represented Wealth. He saw in Dolly not so much a beautiful woman as a rich-looking woman. Although Soapy had contrived, with subtle reasoning, to head her off from the extensive purchases which she had contemplated making in preparation for her visit to Rudge, Dolly undoubtedly took the eye. She was, as she would have put it herself, a snappy dresser, and in Chas. Bywater’s mind she awoke roseate visions of large orders for face creams, imported scents and expensive bath salts.

Emily, it was evident, regarded Mrs. Molloy as Perfection. A dog who, as a rule, kept herself to herself and looked on the world with a cool and rather sardonic eye, she had conceived for Dolly the moment they met one of those capricious adorations which come occasionally to the most hard-boiled Welsh terriers. Hastily swallowing her cough drop, she bounded up and fawned on her.

So far, the reactions caused by the newcomer’s entrance have been unmixedly favourable. It is only when we come to Pat that we find Disapproval rearing its ugly head.

“Disapproval,” indeed, is a mild and inadequate word. “Loathing” would be more correct. Where Colonel Wyvern beheld beauty and Mr. Bywater opulence, Pat saw only flashiness, vulgarity, and general horribleness. Piercing with woman’s intuitive eye through an outer crust which to vapid and irreflective males might possibly seem attractive, Pat saw Dolly as a vampire and a menace—the sort of woman who goes about the place ensnaring miserable fat-headed innocent young men who have lived all their lives in the country and so lack the experience to see through females of her type.

Hussar *

A light cavalry regiment, deriving its title and some of its ceremonial dress from earlier Central European mounted forces.

vapid and irreflective *

See the notes to episode 5 of The Head of Kay’s for the literary background of this term.

vampire *

Church organ fund... (Ch. 5; page 73)

The regular income of Anglican churches comes mostly from land owned by

the Church Commissioners. This tends to be only barely enough to pay the

clergy, so charity work, social activities and major repairs to church

buildings usually require additional funds from voluntary donations.

The charities listed are mostly obvious. Many churches used to organise

social events for church members under the name Pleasant Sunday Afternoons

(PSA) — presumably Pleasant Sunday Evenings are a variant on this.

A curate is a junior member of the clergy who assists the vicar of a parish.

There would have been at least one in most larger parishes. An Additional

Curate is one not provided for in the regular income of the parish:

the Additional Curates Society is an Anglican charity which has funded

such posts in many poorer parishes since Victorian times.

the actual bag *

The Reverend Alistair uses “bag” in the sporting sense of the quantity of game, fish, etc. shot or caught in one outing, or figuratively the successful output of the day’s efforts.

Five shillings gone—just like that! *

The US magazine serial and US book omit the exclamation point and continue:

—and every moment now he was expecting his nephew John to walk in and increase his expenditure. For just after breakfast John had asked if he could have a word with him later on in the morning, and Mr. Carmody knew what that meant.

John ran the Hall’s dairy farm, and he was always coming to Mr. Carmody for money to buy exotic machinery which could not, the latter considered, be really necessary. To Mr. Carmody a dairy farm was a straight issue between man and cow. You backed the cow up against a wall, secured its milk, and there you were. John always seemed to want to make the thing so complicated and difficult, and only the fact that he also made it pay induced his uncle ever to accede to his monstrous demands.

…never set eyes upon a baser document. *

US and UK magazines and US book have a long passage following this:

He was shuddering at the depths of depravity which it revealed, when the door opened and John came in. Mr. Carmody beheld him and shuddered. John—he could tell it by his eye—was planning another bad dent in the budget.

“Oh, Uncle Lester,” said John.

“Well?” said Mr. Carmody hopelessly.

“I think we ought to have some new Alpha Separators.”

“What?”

“Alpha Separators.”

“Why?”

“We need them.”

“Why?”

“The old ones are past their work.”

“What,” inquired Mr. Carmody, “is an Alpha Separator?”

John said it was an Alpha Separator.

There was a pause. John, who appeared to have something on his mind these days, stared gloomily at the carpet. Mr. Carmody shifted in his chair.

“Very well,” he said.

“And new tractors,” said John. “And we could do with a few harrows.”

“Why do you want harrows?”

“For harrowing.”

Even Mr. Carmody, anxious though he was to find flaws in the other’s reasoning, could see that this might well be so. Try harrowing without harrows, and you are handicapped from the start. But why harrow at all? That was what seemed to him superfluous and wasteful. Still, he supposed it was unavoidable. After all, John had been carefully trained at an agricultural college after leaving Oxford and presumably knew.

“Very well,” he said.

“All right,” said John.

He went out, and Mr. Carmody experienced a little relief at the thought that he had now heard all this morning’s bad news.

But dairy farmers have second thoughts. The door opened again.

“I was forgetting,” said John, poking his head in.

Mr. Carmody uttered a low moan.

“We want some Thomas tap-cinders.”

“Thomas what?”

“Tap-cinders.”

“Thomas tap-cinders?”

“Thomas tap-cinders.”

Mr. Carmody swallowed unhappily. He knew it was no use asking what these mysterious implements were, for his nephew would simply reply that they were Thomas tap-cinders or that they were something invented by a Mr. Thomas for the purpose of cinder-tapping, leaving his brain in the same addled condition in which it was at present. If John wished to tap cinders, he supposed he must humour him.

“Very well,” he said dully.

He held his breath for a few moments after the door had closed once more, then, gathering at length that the assault on his purse was over, expelled it in a long sigh and gave himself up to bleak meditation.

For Alpha Separators, see the note below.

…little to view with alarm. *

US and UK magazines and US book insert following this:

He was sitting pretty, and he admitted it.

churl ... scurvy knave (Ch. 5; page 74)

In Anglo-Saxon times, churl was the lowest category of freeman.

After the Norman Conquest most churls were reduced to the status of villein

(i.e. a peasant who holds his land in return for feudal service to his

lord), and the word also took on this sense.

A knave in feudal times was a male domestic servant. The adjective

scurvy, in the sense of disreputable, worthless, is a 16th century

word, so the expression “scurvy knave,” though popular with

historical novelists, is a little anachronistic.

Modern sons of the soil *

In the US and UK magazines and US book, this phrase is replaced simply with “They”.

He stood at the window and looked out on the sunlit garden. *

In the US and UK magazines and US book, he “wandered to” the window instead, and looked out “at” the sunlit garden.

blue bird (Ch. 5; page 74)

The association of the ‘blue bird’ with elusive happiness comes from Maeterlinck’s play L’Oiseau bleu (translated into English in 1909). Wodehouse uses this image quite often: cf. e.g. “The Crime Wave at Blandings”, Money in the Bank, and Cocktail Time.

July ... golden wings (Ch. 5; page 74)

This may not be a specific allusion, as golden wings are something of

a literary cliché. If looking for this phrase, it would even be possible

to make a case here for “Va, pensiero” from Nabucco..!

Burns’s song “Highland Mary” doesn’t use the exact

expression, but it does associate “the golden hours on angel wings”

specifically with summer.

How sweetly bloom’d the gay, green birk,

How rich the hawthorn’s blossom,

As underneath their fragrant shade,

I clasp’d her to my bosom!

The golden Hours on angel wings,

Flew o’er me and my Dearie;

For dear to me, as light and life,

Was my sweet Highland Mary.

Robert Burns: Highland Mary 9–16

manufacturing diamonds out of coal-tar (Ch. 5; page 75)

Synthetic industrial diamonds (made from graphite, not coal-tar) were first successfully produced about 25 years after the publication of Money for Nothing.

Human Sardine (Ch. 5; page 75) °

Sardines are normally sold packed in vegetable oil and tinned/canned.

“You are a stranger in England,” *

In the US and UK magazines and US book, this is more specific to the vicinity:

“You are a stranger here,”

Worcester is only seven miles away, Birmingham is only eighteen (Ch. 5; page 75)

As Norman Murphy has pointed out, Droitwich is the only place that could

fit this description. Wodehouse was staying in Droitwich during at least

some of the time he was writing this book.

Droitwich is a small town which originally developed as a centre for salt

extraction. When the salt industry started to decline in the late 19th

century, the place rebranded itself as a Spa offering brine baths.

N.T.P. Murphy: In Search of Blandings (1986), p. 205

Job (Ch. 5; page 76)

In the Book of Job, in the Bible, Job is a respectable, god-fearing and reasonably wealthy man, upon whom God inflicts a remarkable series of catastrophes to prove a theological point.

First in war... (Ch. 5; page 77)

To the memory of the Man, first in war, first in peace, and first in the hearts of his countrymen.

Henry Lee: Memoirs (Eulogy on George Washington)

What did Gladstone say in ’88? (Ch. 5; page 77)

W.E. Gladstone (1809–1898), leader of the Liberal Party, was Prime Minister

three times. He doesn’t seem to have said anything especially notable

in 1888, a period when he was out of office.

Ronnie is (mis-)quoting a remark usually attributed to Abraham Lincoln.

You can fool some of the people all of the time, and all of the people some of the time, but you can not fool all of the people all of the time.

Abraham Lincoln (attributed)

John D. Rockefeller (Ch. 5; page 78)

John D. Rockefeller (1839–1937) — Founder of the Standard Oil Company, reputedly the world’s first billionaire. Donated more than US$ 540 million to charitable causes.

Charley Schwab (Ch. 5; page 78) °

Charles M. Schwab (1862–1939). An American steel tycoon who started out working in one of Carnegie’s steelmills — first president of United States Steel, was running the Bethlehem Steel Corporation at the time Wodehouse was writing.

Charles R. Schwab, founder of the present-day investment corporation, is not a relative of the steel Schwab.

how much cash he could get for its contents *

The US and UK magazines and US book replace “its contents” with “this Velasquez or this Gainsborough”.

the iron entered into Lester Carmody’s soul *

A traditional phrase in the Book of Common Prayer version of the Psalms, deriving from Miles Coverdale’s 1539 English version, relying on a mistranslation of a Hebrew phrase in Psalm 105:18. Most modern translations render this as “he was put in irons” or in fetters, but the Latin Vulgate had it as ferrum pertransit animam ejus which says that the iron entered his soul.

Elizabethan salt cellar (Ch. 5; page 81) °

In medieval times, a salt-cellar (often just a box or pot) would be placed

in the middle of the table, marking the boundary between the parts where