Meet Mr. Mulliner

by

P. G. Wodehouse

Literary and Cultural References

This is part of an ongoing effort by the members of the Blandings Yahoo! Group to document references, allusions, quotations, etc. in the works of P. G. Wodehouse. These notes are by Neil Midkiff, with contributions from others as noted below.

Meet Mr. Mulliner was first published in the UK by Herbert Jenkins Ltd. on 27 September 1927, and appeared in the US published by Doubleday, Doran & Co. on 2 March 1928. The book is dedicated to the Earl of Oxford and Asquith. The nine stories had appeared in magazines from 1925 through 1927, sometimes in slightly different versions. Further details about the magazine appearances can be found at Neil Midkiff’s web page of the Wodehouse short stories.

Meet Mr. Mulliner was first published in the UK by Herbert Jenkins Ltd. on 27 September 1927, and appeared in the US published by Doubleday, Doran & Co. on 2 March 1928. The book is dedicated to the Earl of Oxford and Asquith. The nine stories had appeared in magazines from 1925 through 1927, sometimes in slightly different versions. Further details about the magazine appearances can be found at Neil Midkiff’s web page of the Wodehouse short stories.

Page references below are to the Herbert Jenkins original UK edition, in which the text runs from p. 7 to p. 312.

The Truth about George

First published in the Strand magazine, July 1926, and in a slightly abridged version in Liberty, July 3, 1926, but with one paragraph not present in other versions.

the Angler’s Rest (p. 7)

In both magazine versions, this is merely “the little fishing inn”; the name “Anglers’ Rest” first appears in “A Slice of Life” in magazines and books. The singular possessive version, as in the heading above, is how it appears in Meet Mr. Mulliner in both UK and US editions, but in this story as collected in The World of Mr. Mulliner it is corrected to “Anglers’ Rest” for consistency with most of the original story appearances.

[A new speculation, March 2022: Could the name be an echo of “The Fisherman’s Rest” in The Scarlet Pimpernel (1905) by Baroness Orczy? This inn at Dover is an important locus in the plot, although there is no one single raconteur there who rules as Mr. Mulliner does at the Anglers’ Rest. —NM]

the story-teller finished his tale and left, he came over to my table (p. 7)

Those of us who have read the Mulliner tales for years might expect “the story-teller” to be Mr. Mulliner himself, but in this, the first of the series, the term refers to the local doctor who had just left, and the “second man” is Mr. Mulliner. In magazines, it is “the other” who “came over to my table” which is clearer than the “he” quoted above from both book editions.

“Fishermen … are traditionally careless of the truth.” (p. 8)

Indeed the OED has citations, mostly American, from the nineteenth century of the phrase “fish story” meaning an unbelieveable yarn, a tall tale. Wodehouse is gently cluing us in that Mr. Mulliner’s stories may well be similarly incredible.

dropsy (p. 8)

Swelling of parts of the body caused by excess watery fluid in the tissues; the modern medical term is edema.

In the US magazine edition, “mumps” is substituted here. See Right Ho, Jeeves.

bought oil stock (p. 8)

Wodehouse had introduced Thomas G. “Soapy” Molloy, champion seller of phony oil stock, the previous year in Sam the Sudden/Sam in the Suburbs (1925).

a gin and ginger-beer (p. 8)

In succeeding tales of the denizens of the Anglers’ Rest, the drinkers are referred to not by name but by their choice of beverage, capitalized almost as a title. A Gin and Ginger Ale in “The Reverent Wooing of Archibald” (1928; in Mr. Mulliner Speaking, 1929), for instance, remarks on the disappearance of the tall, curvaceous, queenly type of girl of earlier days. This initial story has at least the germ of this sort of identification here.

“My name is Mulliner.” (p. 9)

We are told in “Came the Dawn” (later in this volume) that a Sieur de Moulinières came over to England with William the Conqueror.

The French word moulinières is feminine plural, for the women who unwound raw silk fibers from silkworm cocoons and twisted them into thread.

cross-word puzzles (p. 10)

See Sam the Sudden.

Eli, the prophet (p. 10)

See Biblia Wodehousiana.

stearine (p. 10)

See A Damsel in Distress.

crepuscular (p. 10)

An adjective with various meanings related to twilight or similar dim illumination or dawning enlightenment; also referring to animals that are active in the twilight.

plumbing (p. 10)

Any guesses for the seven-letter word?

poppet-valves (p. 11)

See Blandings Castle and Elsewhere. Wodehouse also mentions poppet-valve manufacturers in ch. 2 of Cocktail Time (1958).

disestablishmentarianism (p. 11)

The advocacy of removing any special control, recognition, or privileges granted by a government to a particular religion or church group.

The antonym made with the prefix anti- was popularly supposed to be the longest word in the English language during my school days. [NM]

she was all the world to him (p. 11)

Her voice is low and sweet

And she’s all the world to me

And for Bonnie Annie Laurie

I’d lay me doon and dee.

: Annie Laurie

precious, beloved, darling, much-loved, highly esteemed or valued (p. 11)

It appears that George uses a thesaurus or book of synonyms so often that he thinks in strings of like terms. Diego Seguí found the source in Richard Soule’s A Dictionary of English Synonymes (1871). Richard Soule (1812–1877) was an American lexicographer.

moth-eaten whiskers (p. 11)

Also sported by the house-agent manager spoken to by Ukridge in “Ukridge Sees Her Through” (1923; in Ukridge, 1925).

“I love a lassie” (p. 12)

George is singing the chorus of a 1906 popular song by Harry Lauder and Gerald Grafton, but substituting “purple” for “bloomin’ ” in the third line and altering the last line from “Mary, ma Scotch bluebell” to refer to his Susan. Sheet music online from the University of Maine. Recording sung by Harry Lauder in 1913 on YouTube, in which Lauder sings “purple” in the third line.

“Yes, sir, that’s my baby” (p. 12)

George’s next song is more up to date; this is the title of a 1925 popular song by Gus Kahn and Walter Donaldson. Sheet music online from York University. Period recording sung by Gene Austin on YouTube.

“If you knew Susie like I know Susie” (p. 13)

Another 1925 popular song, by B. G. DeSylva. Sheet music online from York University. 1925 recording sung by Eddie Cantor on YouTube.

ninety-seven point five six nine recurring (p. 13)

As with other statistics quoted by Wodehouse’s “experts” this is not only absurdly precise; this one is mathematically illiterate. A recurring decimal fraction with infinitely repeated nines is numerically indistinguishable from rounding up, so 97.5699999…% is tantamount to 97.57%.

Gunga Din (p. 14)

A famous narrative poem by Kipling; see online text at the Poetry Foundation. Many of Wodehouse’s characters recite it.

putting the tips of his fingers together (p. 14)

Wodehouse regards this as an appropriate pose for various professionals when giving advice, including detectives (perhaps because Sherlock Holmes is described as doing it in five of the twelve stories in the Adventures), lawyers, doctors, and other specialists.

inferiority complex (p. 14)

A fairly new term in popular culture at the time, based on the psychoanalytic theories of Freud and Adler; outside of professional texts the earliest OED citations in print are from the mid-1920s.

suppressed desires or introverted inhibitions or something (p. 14)

Just enough vagueness is present here for Wodehouse to give a subtle laugh at those who were using the new terms of psychology as if by giving something a name it had thereby been explained.

a fee of five guineas (p. 14)

Equal to five pounds and five shillings at the time; see Ukridge. The Bank of England inflation calculator suggests a factor of 62.5 from 1926 to 2020 in consumer price index terms, so the rough equivalent would be £330 or US$450 today.

no Mulliner has ever shirked an unpleasant duty (p. 15)

Mr. Mulliner makes mostly positive claims for his extended family, but occasionally makes negative ones.

No Mulliner has ever taken a prize at a cat show. No Mulliner, indeed, to the best of my knowledge, has even been entered for such a competition.

“Came the Dawn” (1927, later in this collection)

choleric look in his eyes (p. 16)

See the Four Temperaments under phlegmatic at Right Ho, Jeeves.

All we Mulliners have been noted for our presence of mind (p. 16)

The first of the many claims made by Mr. Mulliner for all the members of his extended family.

There is probably no family on earth more nicely scrupulous as regards keeping its promises than the Mulliners

Later in the same story, p. 22.

one of those inspirations which frequently come to Mulliners

Later in the same story, p. 26.

All we Mulliners have been athletes

Later in the same story, p. 31.

though—like all the Mulliners—a man of striking personal charm

“A Slice of Life” (1926; later in this collection)

like all the Mulliners, he was as brave as a lion

“A Slice of Life” (1926; later in this collection)

Augustine, who, like all the Mulliners, loved the truth and hated any form of deception

“Mulliner’s Buck-U-Uppo” (1926; later in this collection)

The commercial interests of the Mulliners have always been far-flung

“The Story of William” (1927; later in this collection)

All the Mulliners have been able speakers

“The Story of William” (1927; later in this collection)

William turned, and being, like all the Mulliners, the soul of modesty

“The Story of William” (1927; later in this collection)

“I generally manage to keep my head fairly well in a crisis. We Mulliners are like that.”

“The Story of William” (1927; later in this collection)

As a family, the Mulliners have always been noted for their reckless courage; and Clarence was no exception to the rule.

“The Romance of a Bulb-Squeezer” (1927; later in this collection)

All we Mulliners have been good trenchermen

“The Romance of a Bulb-Squeezer” (1927; later in this collection)

gifted though the Mulliners have been in virtually every branch of life and sport, few of us have ever taken kindly to golf

“Those in Peril on the Tee” (1927; in Mr. Mulliner Speaking, 1929)

the old canny strain of the Mulliners came out in him

“The Reverent Wooing of Archibald” (1928; in Mr. Mulliner Speaking, 1929)

Essentially a modest man, like all the Mulliners

“The Reverent Wooing of Archibald” (1928; in Mr. Mulliner Speaking, 1929)

Handsome, like all the Mulliners

“The Ordeal of Osbert Mulliner” (1928; in Mr. Mulliner Speaking, 1929)

Though, like all the Mulliners, a clear thinker

“The Ordeal of Osbert Mulliner” (1928; in Mr. Mulliner Speaking, 1929)

It has been frequently said of the Mulliners that you may perplex but you cannot baffle them.

“The Ordeal of Osbert Mulliner” (1928; in Mr. Mulliner Speaking, 1929)

like all the Mulliners, his personal appearance was engaging and even—from certain angles—fascinating.

“The Man Who Gave Up Smoking” (1929; in Mr. Mulliner Speaking, 1929)

The Mulliners are by nature a courteous family

“The Man Who Gave Up Smoking” (1929; in Mr. Mulliner Speaking, 1929)

It is characteristic of the Mulliners as a family that, however sore the straits in which they find themselves, they never wholly lose their presence of mind.

“The Story of Cedric” (1929; in Mr. Mulliner Speaking, 1929)

All the Mulliners are clear thinkers

“The Story of Cedric” (1929; in Mr. Mulliner Speaking, 1929)

“Cupid,” proceeded Mr. Mulliner, “has always found the family to which I belong a ready mark for his bow. Our hearts are warm, our passions quick.”

“Unpleasantness at Bludleigh Court” (1929; in Mr. Mulliner Speaking, 1929)

as I say, we Mulliners are quick workers

“Unpleasantness at Bludleigh Court” (1929; in Mr. Mulliner Speaking, 1929)

Like all the Mulliners on the female side, however distantly removed from the main branch, she is remarkably beautiful.

“Something Squishy” (as revised for Mr. Mulliner Speaking, 1929)

She … was fascinated … by the regularity of his features, which, as is the case with all the Mulliners, was considerable

“The Smile That Wins” (1931; in Mulliner Nights, 1933)

a clear voice which, like that of all the Mulliners, however distant from the main branch, was beautifully modulated

“The Story of Webster” (1931; in Mulliner Nights, 1933)

Sturdy common sense is always a quality of the Mulliners, even of the less mentally gifted of the family.

“The Knightly Quest of Mervyn” (as rewritten for Mulliner Nights, 1933)

like all the Mulliners, he was keenly intuitive

“The Voice from the Past” (1931; in Mulliner Nights, 1933)

Sacheverell retained undiminished the clearness of mind which characterizes Mulliners in times of crisis.

“The Voice from the Past” (1931; in Mulliner Nights, 1933)

Eustace, … like so many of the Mulliners, had a strong vein of the poetic in him.

“Open House” (1932; in Mulliner Nights, 1933)

Something of these feelings he would have liked to put into words, but the Mulliners are famous for their chivalry.

“Best Seller” (1930; in Mulliner Nights, 1933)

Like all the Mulliners, [Augustine] was at heart a man of reckless courage.

“Gala Night” (1930; in Mulliner Nights, 1933)

Like all the Mulliners, my distant connection Wilmot had always been a scrupulously temperate man.

“The Nodder” (1933; in Blandings Castle and Elsewhere, 1935)

Like all the Mulliners, his attitude towards Woman had until recently been one of reverence and unfailing courtesy.

“The Juice of an Orange” (1933; in Blandings Castle and Elsewhere, 1935)

All the Mulliners are men of spirit

“The Castaways” (1933; in Blandings Castle and Elsewhere, 1935)

All the Mulliners are the soul of honour

“The Castaways” (1933; in Blandings Castle and Elsewhere, 1935)

My nephew Archibald, like all the Mulliners, is of an honest and candid disposition, incapable of subterfuge…

“Archibald and the Masses” (1935; in Young Men in Spats, 1936)

anything in the nature of eavesdropping was as repugnant [to Mordred] as it has always been to all the Mulliners…

“The Fiery Wooing of Mordred” (1934; in Young Men in Spats, 1936)

Augustus, like all the Mulliners, was a man of action.

“The Right Approach” (as revised for A Few Quick Ones, 1959)

the work of a moment (p. 16)

See A Damsel in Distress.

To get to East Wobsley … change at Ippleton and take the branch-line (p. 17)

Wodehouse apparently enjoyed Paul Rubens’s 1905 musical play Mr. Popple (of Ippleton), in which you have to change to a branch line train at East Wobsley to get to Ippleton, where Popple raises rabbits. Wodehouse remembered these place names, reusing them in “Resting”, Mike, and “All About Shakespeare”. In this story the towns are named in the reverse order on the branch line.

Emperor of Abyssinia (p. 19)

Abyssinia was an alternate name (derived from Arabic) applied by foreigners to the Ethiopian Empire, which at the time of this story’s writing had shaken off one attempt by Italy at conquest in the 1890s, and was independent until a second war in 1935–36 resulted in an Italian victory. It was ruled by Empress Zewditu I (1876–1930) from 1916 through 1930, so there was in fact no “Emperor of Abyssinia” when this story was written.

Shakespeare’s dictum that a friend, when found, should be grappled to you with hooks of steel (p. 19)

A slight misquotation from Hamlet, in which Polonius recommends “hoops of steel”; see Shakespeare Quotations and Allusions in Wodehouse.

[Omitted in US magazine appearance.]

the machine which, in exchange for a penny placed in the slot marked “Matches,” would supply a package of wholesome butter-scotch (p. 20)

“You insert your penny. You … hope for wax vestas, and you get butterscotch.”

A Prefect’s Uncle, ch. 15 (1903)

Even a penny-in-the-slot machine treats you better than that. It may give you hairpins when you want matches, but at least it takes some notice of you.

“Ahead of Schedule” (1911; in The Man Upstairs, 1914)

A confused noise within (p. 22)

See Shakespeare Quotations and Allusions in Wodehouse.

George … took refuge under the seat … perceived feminine ankles (p. 22)

Later the same year, in The Small Bachelor, another George, George Finch, has a very similar experience: he is hiding under a bed when the first thing he sees is an ankle clad in a silk stocking.

Swedish exercises (p. 24)

See Right Ho, Jeeves.

the position of Robinson Crusoe when he saw the footprint in the sand (p. 25)

See The Girl on the Boat.

a full thermos-flask (p. 26)

The principle of making a double-walled bottle which is insulated from heat transfer by removing most of the air from the gap between the inner and outer bottles was invented in 1892 by the Scottish scientist Sir James Dewar; his initial vacuum flask was made of brass. In 1904 two German glassblowers developed this into a commercial product which they named Thermos. Their trademark became a household name for this and similar products, and here in 1926 Wodehouse is using it generically; the company lost their US trademark rights in 1963. But the US magazine appearance in Liberty calls it a vacuum bottle instead here, reserving “thermos” for George’s second song.

In both US and UK magazine versions, instead of “full” before the container, the phrase “full of the right stuff” appears after the name of the container. Possibly “the right stuff” was dropped for the book versions to avoid confusion, as some of Wodehouse’s characters use that phrase for alcoholic liquor. See The Inimitable Jeeves.

a sort of sizzling sound like a cockroach calling to its young (p. 26)

The rich contralto of a female novelist calling to its young had broken the stillness of the summer afternoon.

“Mr. Potter Takes a Rest Cure” (1926; in Blandings Castle and Elsewhere, 1935)

…there has always been something distinctive and individual about Gussie’s timbre, reminding the hearer partly of an escape of gas from a gas pipe and partly of a sheep calling to its young in the lambing season.

The Code of the Woosters, ch. 3 (1938)

Say it with music—that was the thing to do. (p. 26)

Irving Berlin wrote “Say It with Music” as the theme song of the Music Box Revue of 1921. Sheet music from Ithaca College. 1921 recording by Paul Whiteman and His Orchestra on YouTube.

“Tea for two and two for tea and me for you and you for me——” (p. 26)

Popular song composed in 1924 by Vincent Youmans, with lyrics by Irving Caesar, from the musical No, No, Nanette. Sheet music from Wikipedia Commons. 1925 recording by Marion Harris on YouTube.

“I have a nice thermos. I have a full thermos…” (p. 27)

George is fitting his own lyrics to the refrain of another song by Youmans and Caesar from No, No, Nanette. The original lyrics are:

I want to be happy

But I won’t be happy

Till I make you happy too;

Life’s really worth living

When we are mirth-giving,

Why can’t I give some to you?

When skies are gray and you say you are blue,

I’ll send the sun smiling through.

I want to be happy

But I won’t be happy

Till I make you happy too.

Two-page PDF of sheet music refrain (opens in a new browser tab or window). 1924 recording on YouTube.

interest, elevate, and amuse (p. 27)

See Leave It to Psmith.

“Hard-Hearted Hanna, the Vamp from Savannah” (p. 28)

Thus in UK book; US and UK magazines and US book have the correct spelling “Hannah” but the original sheet music gives the title as “Hard Hearted Hannah (The Vamp Of Savannah).” This 1924 song in ragtime rhythms is by Jack Yellen, Milton Ager, Bob Bigelow, and Chas. Bates. It would indeed be difficult to fit new words to its tricky rhythms. A recent piano-vocal performance with the sheet music displayed on YouTube.

points (p. 28)

The British term for a railroad switch, in which tapering movable rails can be set to direct trains to one or the other branch of a Y-shaped junction.

rocketing pheasant (p. 29)

See Right Ho, Jeeves.

navvies (p. 30)

mob-scene which would have made David W. Griffith scream with delight (p. 31)

Griffith (1875–1948) was the producer/director of some of the earliest silent film spectacles with crowds of thousands on enormous sets, such as The Birth of a Nation (1915) and Intolerance (1916).

Guest Night at the Royal Automobile Club (p. 31)

Compare:

On every side, merry matrons sat calling each other names on doorsteps. Cheery cats fought among the garbage-pails. From the busy public-houses came the sound of mouth-organ and song. While, as for the children, who were present in enormous quantities, so far from crying for bread, as he had been led to expect, they were playing hop-scotch all over the pavements. The whole atmosphere, in a word, was, he tells me, more like that of Guest Night at the National Liberal Club than anything he had ever encountered.

“Archibald and the Masses” (1935; in Young Men in Spats, 1936) (found by Diego Seguí)

The US magazine appearance in Liberty omitted the clause, ending the sentence at “delight.”

It is difficult to say precisely (p. 31)

Magazine versions have an additional paragraph preceding this passage, here quoted from Liberty:

The behavior of his fellow traveler did nothing to allay the growing turmoil in George’s soul. She had sprung from the train, and was now standing with her arms around the neck of one of the navvies. In the intervals of allowing her tears to trickle down the man’s spine, she was proclaiming in a voice of extraordinary power and clearness that George was an escaped lunatic and had tried to murder her with a bomb.

sang-froid (p. 31)

French for “coolness of blood”; calmness, poise.

address (p. 31)

A now-rare sense of this word, having to do with the quality of being adroit, resourceful, prepared, ready and able to do something. The OED has only one citation from the twentieth century.

All we Mulliners have been athletes (p. 31)

See above, p. 16.

east as far as Little-Wigmarsh-in-the-Dell and as far west as Higgleford-cum-Wortlebury-beneath-the-Hill (p. 33)

These were such glorious examples of Wodehouse’s ability to mimic the extended style of British place names that they appealed to American humorist Will Cuppy, who in his 1929 How to Be a Hermit wrote of naming his little island shack:

In more literary moments I think of it as one of those P. G. Wodehouse places, but I never can decide between East Wobsley, Little-Wigmarsh-in-the-Dell, Lower-Briskett-in-the-Midden, and Higgleford-cum-Wortlebury-beneath-the-Hill.

Wodehouse himself revisited them in “Christmas in New York” (Punch, 23 December 1953):

I begin to see that there are certain features of the festive season in these parts which distinguish it from the f. s. in—say—Ashton-under-Lyne or such places as Little-Wigmarsh-in-the-Dell and Higgleford-cum-Wortleberry-Beneath-the-Hill.

Diego Seguí found the placename Wigmarsh in Shropshire, parish of Ruyton, northwest of Shrewsbury.

Lesser-Snodsbury-in-the-Vale (p. 33)

There is a real village of Upton Snodsbury in Worcestershire, and Wodehouse would appropriate part of its name for Aunt Dahlia’s local town Market Snodsbury as well.

known to its builder as Chatsworth (p. 34)

It was common for modest family homes to be named after grand country houses and palaces. Chatsworth, near Bakewell in Derbyshire, is the estate of the Dukes of Devonshire.

sentiments warmer and deeper than those of ordinary friendship (p. 36)

For two different comments on this phrase, see Laughing Gas and Thank You, Jeeves.

wife, married woman, matron, spouse, help-meet, consort (p. 37)

For help-meet see Biblia Wodehousiana.

A Slice of Life

First published in the Strand magazine, August 1926, and in Liberty, August 7, 1926, including a few phrases not present in other versions.

“The Vicissitudes of Vera” (p. 39)

Reminiscent of the titles of silent-film cliffhanger serials starring intrepid heroines, especially The Perils of Pauline (1914), but also The Hazards of Helen, The Adventures of Kathlyn, The Exploits of Elaine, and several others.

Wodehouse apparently associated the name Vera with actresses; he mentioned the name “Vera Dalrymple” as early as 1902 in “An Unfinished Collection”, and as late as 1973 in Bachelors Anonymous an actress named Vera Dalrymple is a bossy star who wants all the good lines. Vera Prebble is a parlourmaid aspiring to be a film star in “The Rise of Minna Nordstrom” (1933; in Blandings Castle and Elsewhere, 1935). Vera Silverton, another actress, appears in “A Room at the Hermitage” (1920; in Indiscretions of Archie, 1921). Vera Upshaw is the daughter of an actress in The Girl in Blue (1970).

the Bijou Dream (p. 39)

See Very Good, Jeeves. The Bijou Dream in the High Street near the Anglers’ Rest is also mentioned in “The Nodder” and “The Rise of Minna Nordstrom” (both 1933; in Blandings Castle and Elsewhere, 1935).

into his toils (p. 39)

Under his influence; into a trap. From the now-archaic word toil for a net or snare that confines a hunted animal. Unrelated to the word of the same spelling for hard work or labor.

“Into a lobster” (p. 39)

In all original editions except the US magazine, the indefinite article is italicized, presumably to depict Miss Postlethwaite’s emphatic pronunciation.

Jack Frobisher (p. 40)

The only other man with the surname Frobisher who is important to a plot is Major Augustus “Tubby” Frobisher in Ring for Jeeves (1953), a friend of Captain Brabazon-Biggar out East of Suez. Gwendoline Gibbs in Frozen Assets/Biffen’s Millions, ch. 4.2 (1964) has been reading a romance story about Captain Eric Frobisher of the Guards, who married the governess. In contrast to these heroic Frobishers, there is a mention of a divorce case of Bingley versus Bingley, Botts and Frobisher in Cocktail Time, ch. 2 (1958). More egregiously, Percy Pilbeam’s middle name is Frobisher in Summer Lightning (1929) and Heavy Weather (1933).

Other heroes named Jack include Captain Jack Cotterleigh of the Irish Guards, Sue Brown’s late father mentioned in Summer Lightning and Heavy Weather; Captain Jack Fosdyke in “Monkey Business” (1932; in Blandings Castle and Elsewhere, 1935), Jack Williams, rugby player for England in “The Fifteenth Man” (1906), and Jack Wilton in “Wilton’s Holiday” (1915). See also the fictional Jack Langdale in The Boys of Dormitory Two, which Marjory Jackson is reading in Jackson Junior / Mike (1909).

hot Scotch with a slice of lemon (p. 41)

This is Mr. Mulliner’s usual drink, mentioned in three of the stories in this collection, and at least two dozen times in later Mulliner stories. Bertie Wooster also mentions this drink at least once:

The short afternoon had turned into a rather chilly, misty sort of evening, the kind of evening that sends a fellow’s thoughts straying off in the direction of hot Scotch and water with a spot of lemon in it.

“Jeeves and the Old School Chum” (1930; in Very Good, Jeeves, 1930)

honest blue eyes … “nothing but the bare truth” (p. 41)

Wodehouse is again warning the reader that Mr. Mulliner may be protesting too much.

the toilet (p. 42)

That is, the dressing table, rather than a water-closet. See Thank You, Jeeves.

ills to which the flesh is heir (p. 42)

A glancing allusion to Hamlet’s most famous soliloquy; see Shakespeare Quotations and Allusions in Wodehouse.

Raven Gipsy Face-Cream (p. 42)

The Liberty US magazine appearance spells it “Gypsy” instead.

though—like all the Mulliners—a man of striking personal charm (p. 42)

See above, p. 16.

Cannes (p. 42)

Apparently Wodehouse’s first reference to this French Riviera resort city. See The Luck of the Bodkins.

wholesome, sunburned complexion (p. 42)

This 1926 story would have been written very differently even five years earlier. The upper classes had traditionally valued pale skin as the sign that they didn’t have to work outdoors like the agricultural classes. But as the South of France became a fashionable winter destination in the middle 1920s and celebrities like fashion designer Coco Chanel returned from there with bronzed skins, a suntan became the mark of those who could afford leisure travel to a sunny spot.

half-crown (p. 43)

A coin worth two shillings and sixpence, one-eighth of a pound. From 1919 through 1952 the coin had a 50% silver content. The Bank of England inflation calculator suggests multiplying 1926 values by 62.5 to yield a 2020 equivalent, so this would be approximately £7.80 in modern terms.

seven shillings and sixpence (p. 43)

Exactly three half-crowns in value, so the larger jar is only slightly more economical. Coincidentally this was also the price of the first British edition of Meet Mr. Mulliner in 1927.

“Jer mong feesh der selar” (p. 44)

A phonetic spelling (for speakers of British English) of the French phrase “Je me’en fiche de cela” which roughly translates as “I don’t care about that” or, more forcefully, “I don’t give a damn.”

the pip in canaries (p. 44)

Any of several respiratory diseases of birds, the avian equivalent of the common cold in humans.

ffinch-ffarrowmere (p. 44)

Our good friends at the Grammarphobia blog have a historical survey of this practice of using a double small f instead of a capital F. They even cite this Wodehouse story at the end of their article: That’s all, ffoulkes!.

Brewer’s Dictionary of Phrase and Fable attributes the practice to a mistaken attempt to render in modern roman type the black-letter manuscript capital F, which often had two broad parallel vertical pen strokes to make the upright of the letter. “Its modern use is an affectation.”

Brewer’s Dictionary of Phrase and Fable attributes the practice to a mistaken attempt to render in modern roman type the black-letter manuscript capital F, which often had two broad parallel vertical pen strokes to make the upright of the letter. “Its modern use is an affectation.”

Bart. (p. 44)

The suffix “Bart.” is short for baronet. Both knights and baronets are addressed as “Sir” followed by their given name, and their wives as “Lady” followed by the family name. But a baronetcy is a hereditary title, passed down to the eldest son, and a knighthood is not inheritable. See Summer Moonshine for more detail and history.

fiend in human shape (p. 46)

See The Mating Season.

vitriol (p. 48)

See Summer Lightning.

bounder (p. 48)

See If I Were You.

mot juste (p. 48)

See Right Ho, Jeeves.

the knuckles stood out white under the strain (p. 49)

See Cocktail Time.

induced this man with bribes to leave suddenly on the plea of an aunt’s illness (p. 49)

In Do Butlers Burgle Banks? (1968) Horace Appleby similarly bribes Coleman the butler to leave suddenly, pleading a father’s illness, and to claim him as a cousin to serve as a substitute.

H2O+b3g4z7–m9z8=g6f5p3x (p. 49)

Other than the chemical formula for water, the rest is gibberish.

well-known costumier’s (p. 50)

Later (p. 59) mentioned as Clarkson; see below.

a cross indicating spot where body was found (p. 50)

See A Damsel in Distress.

a cast in one eye (p. 51)

A slight squint, or a turning of the eye a little to one side.

[John Peters] was not a particularly successful beamer, being hampered by a cast in one eye which gave him a truculent and sinister look.…

Three Men and a Maid/The Girl on the Boat, ch. 8.1 (1922)

“There was a copper with a cast in one eye who kept pinching [Balsam] for street betting.”

A Pelican at Blandings, ch. 6.1 (1969)

like all the Mulliners, he was as brave as a lion (p. 51)

See above, p. 16.

stiffish oxygen and potassium (p. 53)

Once again, chemical gibberish. Potassium in its pure form is highly reactive, a soft metal that easily cuts with a knife. If dropped into water, it combines so readily with the oxygen in the water that the hydrogen is freed and set ablaze by the heat generated as the potassium is oxidized. YouTube video showing potassium metal added to water.

trinitrotoluol (p. 53)

An explosive chemical, commonly called TNT. See A Damsel in Distress.

sold in America as champagne (p. 53)

It was not only in America that counterfeit wines were marketed. In Wodehouse’s early journalism career, an item in the “By the Way” column in the Globe newspaper, June 13, 1903, noted that “The manufacture of weird wines is becoming quite an art.” The reference is to The Lancet of the same date, in an article called “Fictitious Wines: Some Interesting Recipes.”

Esquimaux (p. 54)

See Young Men in Spats.

If he can get at the port (p. 56)

Port, both sweeter and more strongly alcoholic than red table wine, was usually reserved for an after-dinner treat for the men at the dinner table after the ladies had withdrawn to the drawing room. The butler, of course, would have access to port whenever he wanted, and many of Wodehouse’s butlers are described as enjoying it themselves. It would be an unusually lax household in which a valet would get the chance to have port with his luncheon.

a third and supplementary chin (p. 56)

See Very Good, Jeeves.

Clarkson (p. 59)

Willy Clarkson (1861–1934), wigmaker and costume designer, took over his father’s business (founded 1833) in 1878.

“Give me that key, you Fiend.”

“ffiend,” corrected Sir Jasper (p. 59)

The US magazine editor or typesetter somewhat spoiled the joke by failing to capitalize “fiend” in the first sentence.

special licence (p. 59)

See Thank You, Jeeves.

Wilfred staggered, and would have fallen (p. 61)

See Ice in the Bedroom.

piebald (p. 62)

Originally referring to a horse or other animal with black and white patches in its coat; more generally, meaning particolored, as explained in her case in the next paragraph.

upper-cut (p. 62)

A boxing blow delivered in an upwards direction, as to the jaw.

the skin you loved to touch (p. 62)

The J. Walter Thompson advertising agency created the slogan “a skin you love to touch” in 1911 for Woodbury’s Facial Soap; by the later 1920s the ads touted “the skin you love to touch.” The slogan was used for many decades, and its trademark registration expired as late as 1994. Sample advertising pages from 1915 and 1924.

Ponto, my little dog (p. 62)

Wodehouse uses this name in at least two ways: as a name for a faithful dog, and in the phrase “since Ponto was a pup.” The name is derived from Spanish and is often applied to a pointer, as in The Pickwick Papers by Dickens, ch. 2.

“I haven’t been to Rector’s since Ponto was a pup.”

The Prince and Betty, ch. 4 (US edition, 1912)

Your annotator has always assumed that this was a classical reference to a dog of antiquity, but searches have so far been unavailing. Indeed, the earliest instances of this phrase so far found have all been from Wodehouse in 1912–1913. Diego Seguí found a similar phrase, “since Heck was a pup” in use since 1908 at least, and found in such famous works as Babbitt (1922) by Sinclair Lewis. It is tempting to speculate that Wodehouse knew this phrase and changed “Heck” to “Ponto”; without additional data this must remain purely a conjecture.

Faithful dogs named Ponto:

I descended the steep cliffside to the cave on the left of the bay, where, guarded by the faithful Ponto, I was accustomed to disrobe…

Margaret Goodwin, preparing to swim in Not George Washington, ch. 1 (1907)

“I meditate on my faithful dog, Ponto, and wish that I had kicked him overnight.”

“The Sluggard” (1914)

poor old Ponto, who had recently handed in his portfolio after holding office for ten years as the Willoughby family dog

“The Awakening of Rollo Podmarsh” (1923; in The Heart of a Goof, 1926)

“…a tombstone with ‘To Ponto, Ever a Faithful Friend’ on it. Where they buried a dog, I guess.”

Money in the Bank, ch. 14 (1942)

“Stories will be swapped, here an earl speaking of some splendid secretary or estate agent, there a duke eulogizing his faithful dog Ponto, and then Lord Shortlands will top the lot with his tale of you.”

Spring Fever, ch. 14 (1948)

four shillings the medium-sized bottle (p. 63)

Further proof that “Wilfred never forgot that he was a business man” (p. 43). Surely any other man would have supplied the remedy as a gift to his sweetheart rather than mentioning its retail price.

Reduc-o, the recognised specific (p. 63)

Presumably the hyphen in the name is meant to influence the pronunciation to a soft “c” as in “reduce.” A specific is a remedy for a particular disease or symptom, especially a name-branded or patent medicine.

Wodehouse liked to create names ending in -o for his fictional specifics, including Nervino in The Little Warrior/Jill the Reckless (1920), Peppo in “Ukridge Rounds a Nasty Corner” (1924), Ease-o later in this story (p. 66), and of course Buck-U-Uppo in the next story. See Hot Water for more.

Sir Jasper’s weight is down under the fifteen stone (p. 66)

Fifteen stone (at 14 pounds per stone) is equal to 210 pounds. Ian Michaud notes that in the magazine versions, both US and UK, his weight is down under the two hundred pounds, which is a greater reduction from 217 pounds than the fifteen stone mentioned in both US and UK book editions.

rung out a blither peal (p. 66)

“All ended happily, and never had the wedding bells in the old village church rung out a blither peal than they did at the subsequent union.”

Three Men and a Maid/The Girl on the Boat, ch. 15/16 (1922).

preparatory school … Eton (p. 67)

See Thank You, Jeeves.

Mulliner’s Buck-U-Uppo

First published in a slightly cut version in Liberty, September 4, 1926 (but with a paragraph about bad boy Tom Poffley not present in other versions), and in the Strand magazine, November 1926. In both US and UK book editions of Meet Mr. Mulliner, the title is shown on the contents page as Mulliner’s Buck-u-Uppo, but these are the only places so far found where the central "U" is not capitalized, other than the erroneous entry in the McIlvaine bibliography.

Gilbert and Sullivan’s “Sorcerer” (p. 68)

The Sorcerer was the first full-length comic opera written by W. S. Gilbert and Arthur Sullivan for their producing partner Richard D’Oyly Carte. It opened at the Opéra Comique in London in 1877. See the Gilbert and Sullivan Archive for further details, including plot summary, full libretto, vocal score, audio files, and more.

Church Organ Fund (p. 68)

Frequently mentioned in Wodehouse as in need of contributions for the upkeep of what is after all a fairly complicated instrument, and one which can be damaged by cold, damp, mice, and other conditions frequently found in buildings like churches which are often vacant and unheated during the course of a week. See also the notes to Money for Nothing.

“These curates frequently have subscription lists up their sleeves and are extremely apt, unless you are very firm, to soak you for a donation to the church-organ fund or something.”

“Buttercup Day” (1925)

“You know, down where I live, in Wiltshire, the local padres always seem to have the deuce of a lot of trouble with their organs. Their church organs, I mean, of course. I’m always getting touched for contributions to organ funds.”

Sam in the Suburbs (ch. 34 of magazine serial)/Sam the Sudden, ch. 23.3 (1925)

The vicar had come seeking subscriptions to the Church Organ Fund, the Mothers’ Pleasant Sunday Evenings, the Distressed Cottagers’ Aid Society, the Stipend of the Additional Curate and the Rudge Lads’ Annual Summer Outing, and there had been moments of mad optimism when he had hoped for as much as a ten-pound note.

Money for Nothing, ch. 5.3 (1928)

“Many’s the time I’ve had an invitation to go and stay for a couple of weeks at some house and wanted to go and found out at the eleventh hour that they were doing A Pantomime Rehearsal or something in aid of the local Church Organ Fund and backed out like a rabbit.”

The Luck of the Bodkins, ch. 17 (1935)

You don’t hear it much nowadays, but at one time you were extraordinarily apt to get it shot at you by bassos at smoking concerts and entertainments in aid of the Church Organ Fund in the old village hall.

“All’s Well with Bingo’ (1937; in The Crime Wave at Blandings, 1937, and Eggs, Beans and Crumpets UK edition, 1940)

His theme was the Church Organ, in aid of which these grim doings had been set afoot, and it was in a vein of pessimism that he spoke of its prospects. The Church Organ, he told us frankly, was in a hell of a bad way. For years it had been going around with holes in its socks, doing the Brother-can-you-spare-a-dime stuff and now it was about due to hand in its dinner pail.

The Mating Season, ch. 22 (1949)

The current pest, he felt morosely, was probably the Vicar, come to try to touch him for a subscription to his church’s organ fund, and he had resolved to stay where he was and let the reverend gentleman go on ringing till his thumb wore out, when he abruptly changed his mind.

Pigs Have Wings, ch. 10.2 (1951)

What, he asked himself bitterly, did the fellow think this was? The revival of Vaudeville? A village concert in aid of the church organ restoration fund?

Ring for Jeeves, ch. 14 (1953)

I was reminded of the time when we did Charley’s Aunt at the Market Snodsbury Town Hall in aid of the local church organ fund…

Jeeves in the Offing (How Right You Are, Jeeves), ch. 15 (1960)

“I played the Usher in Trial by Jury once in my younger days. At a village in Hampshire in aid of the church organ fund.”

“Life with Freddie” (in Plum Pie, 1966)

“He wanted to cry on my shoulder about the church organ, which apparently needs vitamin shots and top dressing with guano and all sorts of things. But nothing, I told him, that a good village concert won’t cure.”

Do Butlers Burgle Banks?, ch. 10 (1968)

“I happened to be talking to the vicar, and he told me what a weight on his mind the church organ was, it being at its last gasp and no money to pay the vet.…”

Aunts Aren’t Gentlemen, ch. 16 (1974)

“Ah me! I was a pa-ale you-oung curate then!” (p. 68)

The refrain of Dr. Daly’s introductory song in The Sorcerer, “Time was when Love and I were well acquainted.”

beefy young fellows (p. 69)

A list of Wodehouse’s athletic curates is in the annotations to vicar … curate at A Damsel in Distress.

[Reference omitted in US magazine version.]

in-the-Midden (p. 69)

Rather an unusual ending for a place name, as a midden is a refuse pile, compost pile, or dung heap in northern British dialect.

meek and mild (p. 69)

Adjectives irrevocably joined in the minds of many who were brought up on the children’s hymn beginning “Gentle Jesus, meek and mild, look upon a little child” (text by Charles Wesley, 1707–1788).

in the ’eighties, or whenever it was (p. 69)

Actually 1877; see above.

heavyweight boxer (p. 70)

Depending on when the Rev. Stanley was attending Cambridge, this class would have had different weight limits. From 1884 to 1913, any boxer over 160 pounds in weight was termed a heavyweight. After 1913, boxers from 161 to 175 pounds were termed light-heavyweight, and a heavyweight was any boxer over 175 pounds.

apse (p. 70)

In church architecture, this refers to a semicircular recess at the altar end of a church, usually with a half-domed or vaulted ceiling above it.

clerestory (p. 70)

In church architecture, this refers to an upper section of windowed walls, admitting light to the nave (center section of the congregational seating), located above the roofs over the side aisles. Mr. Mulliner is probably not remembering the actual pumpkin debate rightly, as there would not usually be any place to locate a pumpkin in the clerestory, and in any case it would be high above eye level if put there.

Cupid makes heroes of us all (p. 70)

Diego Seguí notes that Shakespeare’s line “Thus conscience does make cowards of us all“ (see Shakespeare Quotations and Allusions in Wodehouse for other allusions to this passage) was adapted by Coleridge into “Conscience makes Heroes of us all.” Diego suggests this as an intermediate source for Wodehouse’s phrase above. An Internet search has so far failed to find any earlier citation for this phrase, so it appears to be a Wodehouse invention.

Augustine, who, like all the Mulliners, loved the truth and hated any form of deception (p. 71)

See above, p. 16.

orphrey (p. 72)

An embroidered ornamental design on a liturgical vestment or altar cloth.

chasuble (p. 72)

A sleeveless mantle covering the body and shoulders, worn over other ecclesiastical garb by the priest or celebrant at Mass or the Eucharist.

Boko (p. 72)

A nickname typically applied to a man with a prominent nose; see Ukridge.

You may remember that I once told you (p. 73)

In “A Slice of Life”, earlier in this collection.

vitamines (p. 74)

This is the original spelling of the word, coined in 1912 by Polish biochemist Casimir Funk, who thought that all the essential nutrients that fell under his classification were nitrogen-containing compounds in the class of amines. By 1920 it was recognized that not all vitamins were chemically amines, so the word lost its final ‘e’ and became vitamins as known today. Clearly Angela Mulliner has not been reading Wilfred’s chemical journals closely.

The Liberty editor substituted the more modern spelling vitamins in the US magazine version.

“Oh, dash!” (p. 75)

A substitute oath, for those who do not want to say “damn.” See A Damsel in Distress.

the dogs (p. 75)

“Dogs” as slang for “feet” has been around in US slang since the early 1910s; Wodehouse had used it in Leave It to Psmith in the voice of “Smooth Lizzie” when talking to her confederate Ed Cootes rather than in her poetess persona as Aileen Peavey.

cloth-head (p. 76)

The OED calls this a colloquialism for someone thick-headed; I have always interpreted it to mean “having no more brains than a rag doll.” The first OED citation is this Wodehouse sentence, but he had used it earlier as well:

“I’ve been wanting a shore job ever since I was cloth-head enough to go to sea.”

Hash Todhunter in Sam in the Suburbs, ch. 12 of magazine serial/Sam the Sudden, ch. 12.1 (1925)

Diego Seguí suggests a parallel with the description of Lord Emsworth as “fluffy-minded” in Something New/Something Fresh.

concrete skull (p. 76)

See Very Good, Jeeves.

lip (p. 76)

Slang for impudence, back-talk, unwanted speech; OED has citations beginning 1821.

The meek shall inherit the earth (p. 77)

See Biblia Wodehousiana.

Mem: Must guard agst this (p. 77)

Two conventional abbreviations: memorandum and against.

beetle-wits (p. 78)

Not cited in the OED; this appears to be Wodehouse’s sole usage. Probably derived from the heavy wooden-headed sledgehammer or maul called a “beetle” as used in paving, demolition, and other industrial tasks, rather than referring to the insect of that name; the tool is figuratively used as “the type of heavy dullness or stupidity” in OED citations from the sixteenth to nineteenth centuries. “Dumb as a bag of hammers” might be the modern equivalent.

[Omitted in US magazine version.]

erasing the words with … a thick-leaded pencil (p. 78)

We use erasing today almost exclusively to mean rubbing marks off paper with a rubber eraser, but erase can also mean to obliterate, to block out so as to make illegible.

[Omitted in US magazine version.]

“Mashed potatoes!” (p. 78)

See Money for Nothing.

The Strand magazine version substitutes “Applesauce!” here; the Liberty version omits the sentence entirely.

hymn for those of riper years at sea (p. 78)

In A Wodehouse Handbook, Norman Murphy called this a “PGW blend of two services in the Book of Common Prayer, ‘The Order of Baptism for those of Riper Years’ and ‘Forms of Prayer to be used at Sea’.”

See The Order of Baptism and Prayers at Sea from the Church of England web pages.

a healthy tramp across the fields (p. 79)

The Liberty magazine version has a paragraph following this sentence which does not appear in any other edition of the story:

On his way through the village he held his head up, nodded cheerfully at passers-by, and even—an act that he had always longed to perform, but for which he had hitherto lacked courage—caught young Tom Poffley, the local bad boy, by one of his large, red ears, and, pinching it, informed him that, if he wanted six of the best on the seat of his corduroy pants, he could insure them by absenting himself from Sunday-school again. Then, whistling, went out across the country.

gaiters (p. 80)

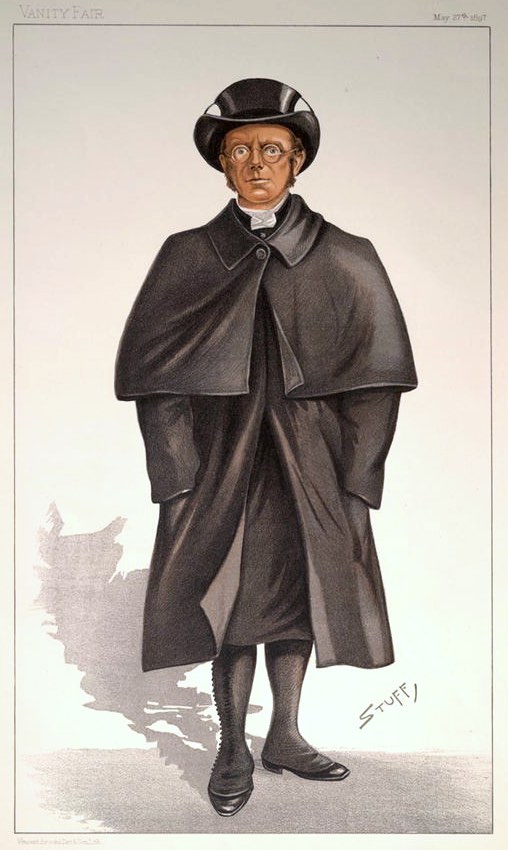

Part of the traditional costume of Anglican bishops, clerical gaiters were protective leggings of black cloth worn over the shoe and lower leg, reaching almost to the knee, buttoned up the side. Their function was originally practical, because bishops historically would be riding on horseback to visit throughout their diocese. At right, the Bishop of Lichfield, from Vanity Fair in 1897.

Part of the traditional costume of Anglican bishops, clerical gaiters were protective leggings of black cloth worn over the shoe and lower leg, reaching almost to the knee, buttoned up the side. Their function was originally practical, because bishops historically would be riding on horseback to visit throughout their diocese. At right, the Bishop of Lichfield, from Vanity Fair in 1897.

dumb friend (p. 80)

See dumb chums in the notes to The Code of the Woosters.

forty-five m.p.h. (p. 81)

See The Girl on the Boat.

The US magazine version has “forty m. p. h.” here.

His eye was not dim (p. 81)

See Biblia Wodehousiana.

Pieface (p. 82)

A nickname given to those with a round, flat face or a typically blank expression. The house detective at the Hotel Cosmopolis, Timothy O’Neill, is called Pie-Face in “Paving the Way for Mabel” (1920; in Indiscretions of Archie, 1921). Occasionally the sobriquet is applied to otherwise anonymous members of the Drones Club in stores from the 1930s.

Great is truth and mighty above all things (p. 83)

See Biblia Wodehousiana.

bishop, his back to the fireplace … hearth-rug (p. 84)

dickey (p. 85)

A false shirt-front and collar, worn under a jacket or dress coat to give the impression of wearing a full shirt.

harlequin (p. 87)

A character from Italian commedia dell’arte and theatrical traditions derived from it such as English pantomime, depicted as playful, nimble, and mischievous. An 1813 citation in the OED mentions “a harlequin-leap through a window.”

sported on the green (p. 88)

See Ukridge.

inked darts (p. 88)

See Right Ho, Jeeves.

hotsy-totsy (p. 89)

See Hot Water.

“I can take them or leave them alone.” (p. 90)

Usually claimed by someone who protests that he is not (or is no longer) addicted to cigarettes, alcoholic drinks, and other tempting indulgences.

As a moderate drinker, you can take your liquor or leave it alone.

Alcoholics Anonymous (the “Big Book”), ch. 12

“If I were you … I would use every effort to prevent this passion for flinging flower-pots from growing upon me. I know you will say that you can take it or leave it alone; that just one more pot won’t hurt you; but can you stop at one?”

Psmith to Baxter in Leave It to Psmith, ch. 11.5 (1923)

“The newts got him. Arrived at man’s estate, he retired to the depths of the country and gave his life up to these dumb chums. I suppose he used to tell himself that he could take them or leave them alone, and then found—too late—that he couldn’t.”

Bertie speaking of Gussie Fink-Nottle in Right Ho, Jeeves, ch. 1 (1934)

I think you should watch yourself in this matter of neck-breaking and check the urge before it gets too strong a grip on you. No doubt you say to yourself that you can take it or leave it alone, but isn’t there the danger of the thing becoming habit-forming?”

Bertie to Spode in Stiff Upper Lip, Jeeves, ch. 14 (1963)

the most consummate address (p. 91)

See page 31, above.

second Sunday before Septuagesima (p. 93)

See Very Good, Jeeves.

Athenæum (p. 94)

See A Damsel in Distress.

a good woman is a wondrous creature (p. 94)

Elin Woodger found this for Norman Murphy’s A Wodehouse Handbook, vol. 2, in an 1839 letter from Tennyson to Emily Sellwood, quoted in The Life and Works of Alfred, Lord Tennyson, vol. 1. The original is very slightly different:

A good woman is a wondrous creature, cleaving to the right and the good in all change, lovely in her youthful comeliness, lovely all her life long in comeliness of heart.

as a jewel of gold in a swine’s snout (p. 95)

See Biblia Wodehousiana.

lobelia (p. 96)

See Leave It to Psmith.

lorgnette (p. 97)

See Summer Lightning.

episcopal (p. 97)

Belonging to or related to the office of a bishop.

jollied her along (p. 97)

Slang for “treated her pleasantly, encouraged her to stay in good humor.”

whistled a few bars of the psalm appointed for the twenty-sixth of June (p. 100)

See Biblia Wodehousiana.

Over the years there have been many musical settings of the psalms, so it is unclear which tune that Augustus would have been whistling.

The Psalter in the Book of Common Prayer is intended to be read through in each month, so it would be the same on the twenty-sixth of January or December as it was for the twenty-sixth of June.

The Morning Prayer for the 26th day begins with Psalm 119:105, “Thy word is a lantern unto my feet: and a light unto my paths” and continues through the psalm. The Evening Prayer for the day concludes with the last verse, Psalm 119:176, “I have gone astray like a sheep that is lost: O seek thy servant, for I do not forget thy commandments.”

Salop (p. 101)

‘Salop’ is a historical name and a conventional abbreviation for the county of Shropshire (from the Anglo-French name, Salopesberia).

C.O.D. (p. 101)

Cash On Delivery, in which the recipient of a parcel pays the carrier upon receiving ordered goods; the carrier then returns the payment (perhaps minus a small fee) to the shipper.

Blessed shall be thy basket and thy store (p. 101)

See Biblia Wodehousiana.

The Bishop’s Move

First published in a slightly abridged version in Liberty, August 20, 1927, and in the Strand magazine, September 1927.

wideawake (p. 102)

A soft felt hat with a broad brim and a low crown; OED citations begin in 1837.

Evensong (p. 102)

A Church of England service held late in the day, with prayers, hymns, Scripture readings, a sermon, and recitations. Bertie Wooster gives a wonderful picture in “The Great Sermon Handicap” (1922):

There’s something about evening service in a country church that makes a fellow feel drowsy and peaceful. Sort of end-of-a-perfect-day feeling. Old Heppenstall was up in the pulpit, and he has a kind of regular, bleating delivery that assists thought. They had left the door open, and the air was full of a mixed scent of trees and honeysuckle and mildew and villagers’ Sunday clothes. As far as the eye could reach, you could see farmers propped up in restful attitudes, breathing heavily; and the children in the congregation who had fidgeted during the earlier part of the proceedings were now lying back in a surfeited sort of coma. The last rays of the setting sun shone through the stained-glass windows, birds were twittering in the trees, the women’s dresses crackled gently in the stillness. Peaceful. That’s what I’m driving at. I felt peaceful. Everybody felt peaceful.

curate (p. 102)

In the Church of England, an assistant to the vicar or rector of a parish.

some gay psalm (p. 103)

See Biblia Wodehousiana.

lumbago (p. 104)

Pain in the muscles of the lower back.

For lo! the winter is past (p. 104)

See Biblia Wodehousiana.

St. Beowulf’s in the West (p. 104)

A rather humorous title for a fictitious church, as Beowulf in the Old English saga lived in pagan Scandinavia of the sixth century and, although heroic, was apparently never canonized then or later.

vacant living (p. 105)

A currently unoccupied position as a vicar or rector of a church; an available job with its accompanying salary.

“Do I click?” (p. 105)

“Am I successful in getting it?” The OED’s first citation of this colloquial sense of click is from 1916, where it is theatrical jargon for going over well with an audience; the second citation is from The Inimitable Jeeves, where in “Pearls Mean Tears” Bertie asks Sidney Hemmingway “Did you click?”—asking if he had won at the Casino.

doesn’t know an alb from a reredos (p. 105)

An alb is a white vestment covering the entire body from shoulders to the feet. A reredos is a covering for the wall at the back of an altar, either an ornamental facing or screen of stone or wood, or (in historical times) a velvet or silk hanging covering that wall.

another along in a minute (p. 106)

A somewhat surprising phrase to use in reference to a church job! See Leave It to Psmith for its more frequent usage in reference to women.

better to dwell in a corner of the housetop (p. 106)

See Biblia Wodehousiana.

A continual dropping in a very rainy day (p. 106)

See Biblia Wodehousiana.

the seventh Henry (p. 107)

King Henry VII of England (1457–1509; ruled 1485–1509), first monarch of the House of Tudor. His father Henry VI had founded Eton College in 1440, so Harchester (fictitious, of course) is not quite as ancient as Eton.

Alma Mater (p. 107)

Latin for bounteous mother; used in English since the seventeenth century for the school or college that nurtured one’s educational years.

inked darts (p. 109)

See Right Ho, Jeeves.

tuck-shop (p. 109)

A small shop in school where boys could buy sweets, buns, ice creams, etc. [NTPM]

baths (p. 109)

Swimming pool (provided both for exercise and cleanliness).

fives courts (p. 109)

See The Pothunters.

gaitered legs (p. 110)

Gaiters are coverings of cloth or leather which, like spats, cover the upper portion of the shoe as well as the ankle, but which also extend upward over the shin, sometimes almost to the knee. This illustration by Charles Crombie [opens in new browser tab or window] to “Mulliner’s Buck-U-Uppo” in the Strand shows the Bishop in a tree, wearing gaiters.

Old Man (p. 111)

A schoolboy’s term for the headmaster; see The Pothunters.

to roll out sonorous periods (p. 112)

See A Damsel in Distress.

individual and distinctive (p. 114)

See Ukridge for an advertising campaign using these words.

specific (p. 115)

A medicine intended to cure or alleviate one particular illness or symptom; a patent medicine.

sang-froid (p. 115)

French: coolness of blood.

a youngish and rather rowdy fifteen (p. 115)

Compare:

He was thirty-six next birthday, but he felt a youngish twenty-one.

“The Man With Two Left Feet” (1916)

“though sixty if a day, he becomes on arriving in London as young as he feels, which is, apparently, a youngish twenty-two.”

A thoughtful Drone, speaking of Lord Ickenham in Uncle Fred in the Springtime, ch. 3 (1939)

Empire builder (p. 116)

See Very Good, Jeeves.

brown boot-polish spread on bread (p. 117)

“Do you remember Macpherson? Left a couple of years ago. His food ran out, so he spread brown-boot polish on bread, and ate that. Got through a slice, too. Wonderful chap!”

Jackson Junior, ch. 18 (1907; in book form as the first half of Mike, 1909)

The reason, for instance, why Thomas Billing, aged eleven, had eaten a slice of bread covered with brown boot-polish, thereby acquiring a severe bout of sickness and a heavy punishment, was that Rupert Atkinson, aged fourteen, and Alexander Jones, aged twelve, had betted him he wouldn’t.

“Creatures of Impulse” (1914)

Peace be on thy walls … Proverbs cxxi. 6. (p. 118)

See Biblia Wodehousiana.

Despite Fr. Rob’s sober comment at Biblia Wodehousiana, quoting Ring and Jaggard, it appears to me [NM] that the erroneous citation was intentional, in order to show the bishop’s state of intoxication, as Proverbs has only 31 chapters. Apparently a copy-editor at the Strand didn’t recognize the joke and amended the citation to the correct Psalms cxxii.7.

pie-faced (p. 121)

See Very Good, Jeeves.

Something attempted, something done had earned a night’s repose (p. 124)

See Right Ho, Jeeves.

the scent of growing things (p. 125)

The air was full of the scent of growing things; strange, shy creatures came and went about him as he walked; down in the woods a nightingale had begun to sing; and there was something grandly majestic in the huge bulk of the castle as it towered against the sky.

Leave It to Psmith, ch. 11.3 (1923)

“Hullo, Uncle Fred. I say, what a lovely evening!”

“Very.”

“The air! The stars! The scent of growing things!”

Uncle Fred in the Springtime, ch. 17 (1939)

“The cool air. The scent of growing things. That is tobacco plant which you can smell, sir.”

Joy in the Morning, ch. 14 (1946)

For the benefit of the latter I will state that it was a nice evening with gentle breezes blowing and stars peeping out and the scent of growing things and all that, and then I can get down to the res.

Aunts Aren’t Gentlemen, ch. 17 (1974)

boys will be boys (p. 125)

See A Damsel in Distress.

shovel-hat (p. 125)

A stiff broad-brimmed hat, curled up at the sides and projecting in front and back with a shovel-shaped curve, as worn by Church of England bishops. Details and images at Wikipedia.

wings like a dove. Psalm xlv. 6 (p. 129)

See Biblia Wodehousiana.

V.C., K.C.I.E., M.V.O. (p. 129)

The General’s honors include the Victoria Cross, Knight Commander of the Order of the Indian Empire, and Member of the Royal Victorian Order.

It was something other than tomatoes that this lad reminded him. (p. 131)

An editing error in the UK first edition; the Strand version has “It was of something other than tomatoes…” here.

the trend of Modern Thought (p. 133)

See The Old Reliable.

I wash my hands of the whole business (p. 133)

See Biblia Wodehousiana.

whale-oil solution (p. 135)

See A Damsel in Distress.

a couple of quid (p. 136)

Lavish wealth for a schoolboy. The Bank of England inflation calculator suggests that the purchasing power of £2 in 1927 is roughly equivalent to that of £100 in 2023.

Hants (p. 136)

Classical abbreviation for Hampshire, used in postal addresses. Derives from Old English Hantescire as used in the Domesday Book.

the wife of thy bosom (p. 136)

See Biblia Wodehousiana.

a bird of the air (p. 137)

See Biblia Wodehousiana.

Came the Dawn

First published in a slightly abridged version in Liberty, June 11, 1927, and in the Strand magazine, July 1927.

stout-and-mild (p. 138)

A combination of two types of brewed beverage: stout is a dark beer (Guinness is a well-known brand) with a lighter ale brewed with a minimal amount of hops (thus “mild” rather than “bitter”). When served in unmixed layers in the glass, it is sometimes also known as a black-and-tan.

There’s a divinity that shapes our ends (p. 138)

From Hamlet: see Shakespeare Quotations and Allusions in Wodehouse; note also that Wodehouse used “Rough-Hew Them How We Will” as a 1910 story title.

tortoiseshells (p. 138)

See The Old Reliable.

“I have never deviated from the truth in my life” (p. 139)

In the first Mr. Mulliner story, the narrator suggests that fisherman are traditionally careless of the truth, but Mr. Mulliner replies:

“I am a fisherman myself, and I have never told a lie in my life.”

always darkest before the dawn (p. 139)

See The Girl in Blue.

gherkin (p. 141)

A small young cucumber used for making pickles.

Nellie Wallace (p. 141)

Born Eleanor Jane Wallis Taylor (1870–1948), Nellie Wallace was an eccentric comedienne and music-hall singer and dancer, who capitalized on an expressive but strong-featured face for humor rather than beauty, accessorizing with tight skirts and quirkily decorated hats.

companionway (p. 142)

A staircase between decks on a boat.

gimp (p. 142)

Pronounced with a soft ‘g’ and more frequently spelled “jimp” this adjective from Scottish and northern England dialect means “slender, delicate, graceful, neat.”

the Mauve Mouse, the Scarlet Centipede… (p. 143)

See under the Mottled Earwig in Young Men in Spats.

never let his left hip know what his right hip was doing (p. 144)

See Biblia Wodehousiana.

old Colonel Charleston’s favourite son (p. 144)

See Money for Nothing.

Sieur de Moulinières (p. 149)

See p. 9, above.

Junior Lipstick Club (p. 147)

This club for younger women is also mentioned in “The Reverent Wooing of Archibald” (1928; in Mr. Mulliner Speaking, 1929/30), and betting on the outcome of an engagement happens in that story too.

coming straight from the stable (p. 147)

Inside information, in horse-racing jargon.

current form (p. 147)

In racing jargon, up-to-date information on a racehorse’s speed, endurance, and so forth.

the above have arrived (p. 148)

In other words, the contestants are ready to begin the race; see another figurative usage in “The Great Sermon Handicap” (1922).

Captain Coe’s final selection (p. 148)

“Captain Coe” was the pseudonym of the sporting editor of The Sketch, who included tips on horses he thought likely to run well.

stick the gaff into Purvis (p. 148)

Literally, harpoon him, as one would a whale; figuratively, to vanquish in romantic combat.

Young Lochinvar (p. 148)

See Right Ho, Jeeves.

red fire (p. 148)

A type of flash powder used for stage-magical flame effects by conjurers and in fantasy scenes in pantomimes and so forth.

walk-over (p. 148)

See Summer Lightning.

five thousand pounds a year (p. 149)

Lancelot is being optimistic here; in purchasing-power terms, this is roughly equivalent to £250,000 in early 2023.

a quire of the best foolscap (p. 149)

A packet of 24 or 25 large sheets of writing paper, each about 16.5 by 13.5 inches in size.

Promethean fire (p. 150)

In Greek mythology, Prometheus was a Titan, who defied other gods by giving fire to humanity. Some versions of the myth give him credit for creating humanity by animating clay figures with the warmth of life. Thus Promethean fire can be thought of as a metaphor for divinely-given intelligence and inspiration.

morceau (p. 151)

French for a morsel or fragment: either a tidbit of food or a short musical, literary, or poetic composition.

threnody (p. 151)

A poem of lamentation for the dead; a dirge.

including the Scandinavian (p. 151)

See Blanding Castle and Elsewhere.

Desolation, Doom, Dyspepsia, and Despair (p. 152)

Adding dyspepsia (bad digestion) to a trio of other calamaties; see The Old Reliable.

eyes were protruding (p. 152–53)

See Thank You, Jeeves.

limp leather, preferably of a violet shade (p. 153)

the late Napoleon from Moscow (p. 154)

See The Old Reliable.

rode back to civilisation (p. 154)

Putney is on the Thames, well within Greater London, so this slur on a respectable suburb must be Lancelot’s artistic distaste for the conventional mode of life of its dwellers.

dumb show (p. 155)

What Americans (but not Britons) would call pantomime: acting without speaking.

Berkeley Square (p. 155)

Berkeley Square is in the centre of the wealthy residential district of Mayfair. [MH]

come out of an egg (p. 155)

Of avian or reptilian appearance. Compare:

little Cooley, a glistening child who had the appearance of having recently been boiled, looked like something that had come out of an egg

Bill the Conqueror, ch. 2.3 (1924)

Cork Street (p. 156)

See Ukridge.

follow the dictates of her heart (p. 160)

See Uncle Fred in the Springtime.

vers libre (p. 160)

See The Girl on the Boat.

she inserted a monocle (p. 161)

Monocle-wearing had been a purely masculine fashion in Victorian and Edwardian times, but some of the female Bright Young Things of the 1920s adopted monocles as a sign of their unconventionality. Gladys Bingley, Lancelot Mulliner’s fiancée, vers-libre poetess Gladys Bingley (in “The Story of Webster” and “Cats Will Be Cats”, 1932), also wears a monocle.

“What’s on the mind besides hair?” (p. 161)

“I say there would appear to be something on your mind besides your hair.”

Archie Moffam in “The Man Who Married an Hotel” (1920; in Indiscretions of Archie, 1921)

George Benham … seemed to have something on his mind besides the artistically straggling mop of black hair which swept down over his brow.

“A Room at the Hermitage” (1920; in Indiscretions of Archie, 1921)

He gave me the impression of a two-hundred-pound curate with something on his mind beside his hair.

Stinker Pinker in Stiff Upper Lip, Jeeves, ch. 3 (1963)

washed his hands of me (p. 161)

See Biblia Wodehousiana.

Yes, love indeed is light from heaven (p. 161)

From Lord Byron, The Giaour (1813)

Give me to live with Love alone (p. 162)

Quoting Laman Blanchard, Dolce far Niente.

When beauty fires the blood (p. 162)

Quoting John Dryden, Cymon and Iphigenia, line 41.

Bradshaw’s Railway Guide (p. 162)

See Summer Moonshine. Compare:

It may, however, be noticed that a good many members of the Bradshaw family possess a keen and rather sinister sense of the humorous, inherited doubtless from their great ancestor, the dry wag who wrote that monument of quiet drollery, “Bradshaw’s Railway Guide.”

“A Shocking Affair” (1903)

The race goes by the form-book (p. 162)

See Thank You, Jeeves.

old crocus (p. 162)

This phrase is apparently unique in Wodehouse’s writings, but possible literary sources include:

“I remember Vickery went ashore with our Carpenter Rigdon—old Crocus we called him.”

Rudyard Kipling, “Mrs. Bathurst” in Traffics and Discoveries (1904)

“You delightful, huffy old crocus,” she said; “just now you are a most happy mixture of Ludovic and the Pelican, without, of course, the imperfections of either.”

Lady Margaret Sackville: “The Adventures of Duchess Ingebrun” (1905)

St. George’s, Hanover Square (p. 162)

Church in the Mayfair district of London, noted for fashionable weddings in fact and fiction, including Lord St. Simon’s in the Sherlock Holmes story “The Adventure of the Noble Bachelor.”

eating plover’s eggs in a new dress to the accompaniment of heavenly music (p. 163)

Compare:

“It’s like eating strawberries and cream in a new dress by moonlight on a summer night, while somebody plays the violin far away in the distance, so that you can just hear it,” she said.

The Prince and Betty, ch. 1 (1912)

a bob (p. 163)

A shilling, one-twentieth of a pound sterling.

Seamore Place from the west (p. 164)

Seamore Place was, at the time, a sharp turnoff to the southeast at the west end of Curzon Street, before Curzon Street was connected through to Park Lane in 1937. On Google Maps today it is labeled as Curzon Square. See A London Inheritance.

Charles Street from the east (p. 164)

Probably best known to Wodehouseans as the location of Aunt Dahlia’s town house at Number 47. In real life, 47 Charles Street was the home of Ian Hay, Wodehouse’s theatrical collaborator.

Tempests may lower and a strong man stand face to face with his soul (p. 165)

In the Liberty magazine version, the smooth-faced man’s purple prose is studded with capital letters through “a Wealthier Wooer,” emphasizing that he is quoting platitudes:

“Tempests may Lower and a Strong Man stand Face to Face with his Soul…”

See also Mr. Mulliner Speaking.

Mammon has conquered Cupid (p. 165)

Personifications of Wealth and Love. Mammon is Biblical, coming from the Aramaic word for wealth or profit; Cupid is from Roman mythology, the god of love portrayed as a young boy.

“That afternoon. Her apartment.” (p. 165)

It is now becoming clear that the smooth-faced man is speaking in the language of silent film title cards, which were used to show changes of time and scene as well as to display dialogue and commentary on the action.

Boost for Hollywood (p. 166)

Compare with the “Boost for Birdsburg” buttons in “Jeeves and the Hard-Boiled Egg” (1917; in Carry On, Jeeves, 1925).

Bigger, Better, and Brighter Motion-Picture Company of Hollywood, Cal. (p. 166)

Besides the fictional Hollywood studios that Wodehouse names after their proprietors, he delights in naming even the upstart outfits in humorous ways, often reminiscent of their own press-agents’s puffery.

writing scenarios out in California for the Flicker Film Company

“The Clicking of Cuthbert” (1921)

“Here’s a cable that came this morning from the Super-Ultra-Art Film Company, offering me a thousand solid dollars for the scenario.”

“Lord Emsworth Acts for the Best” (1926; in Blandings Castle and Elsewhere, 1935)

The Finer and Better Motion Picture Company of Hollywood, California

The Small Bachelor, ch. 3.2 (1926/27)

Jacob Z. Schnellenhamer … his own company, the Colossal-Exquisite

“The Rise of Minna Nordstrom” (1933; in Blandings Castle and Elsewhere, 1935)

a fellow that can register the way you can (p. 166)

See Right Ho, Jeeves.

adenoids (p. 167)

See Summer Lightning.

beazle (p. 168)

Spelled thus in all original editions, although beazel is more common in Wodehouse; see Hot Water for more on the term.

ten thousand dollars a week (p. 168)

Measuringworth.com gives a range of relative values to account for inflation since 1927; a simple consumer-price-index adjustment would give roughly $172,000 in purchasing power in early 2023. Their scale of worth for amounts received as a compensation would compare to over $600,000 in modern terms.

Came the Dawn! (p. 169)

A cliché of silent-film title cards; see Blandings Castle and Elsewhere.

The Story of William

First published as “It Was Only a Fire” in a slightly abridged version in Liberty, April 9, 1927, and in the Strand magazine, May 1927.

Hands Across the Sea (p. 170)

Title of an 1899 military march by John Philip Sousa, commemmorating an incident in the Spanish-American War in which a British Navy vessel assisted Admiral Dewey’s fleet at Manila Bay. Audio files and sheet music cover at Wikipedia.

Jewel State of the Union (p. 171)

Though this is capitalized as if it were a well-known slogan, a Google search finds no earlier instance of this phrase.

stalwart men and womanly women (p. 171)

This phrase had been used earlier by Ralph Stock in “The Recipe for Rubber” (1912 serial in Pearson’s; 1913 as a book).

“That was not an earthquake. It was a fire.” (p. 171)

It is true that much of the damage to San Francisco on April 18, 1906 was caused by fire, but many of those fires were initially started by a major earthquake that ruptured gas mains. Later, even more fires were spread by mistaken use of explosives when trying to create a firebreak to keep the fires contained to a small area. Initial use of dynamite to clear out damaged buildings was proper, but when no more dynamite was available, the use of black powder and other “low explosives” actually set more fires than it prevented.

The commercial interests of the Mulliners have always been far-flung (p. 172)

See above, p. 16.

the Golden Gate (p. 173)

The famous suspension bridge across the Golden Gate has usurped the name in popular imagination, but long before the bridge, the strait that connects San Francisco Bay to the Pacific Ocean was called the Golden Gate. Explorer John C. Frémont christened it in 1846, even before the discovery of gold in California. So in 1906, when this story’s action is set, and even in 1927, when the story was first published, “Golden Gate” meant simply the strait.

When this story was written, the bridge had been authorized by an act of the California legislature, but the district set up to finance it was not incorporated until 1928, and construction would not begin until 1933; the bridge opened in 1937.

All the Mulliners have been able speakers (p. 173)

See above, p. 16.

the greatest compliment a man can bestow on a woman (p. 173)

bounder (p. 174)

See If I Were You.

hawk-faced (p. 174)

Wodehouse associates this description with Sherlock Holmes and, from him, with detectives in general. Holmes has a hawk-like nose in “The Red-Headed League” but I have not been able to find “hawk-faced” in Conan Doyle’s Holmes stories.

Lois Denham, the willowy recipient of sunbursts from her friend Izzy of the hat-checks, came by in company with a sallow, hawk-faced young man with a furtive eye, whom Jill took—correctly—to be Izzy himself.

Jill the Reckless/The Little Warrior, ch. 15.1 (1920)