The Captain, July 1911

TO-DAY’S moral story: The brief début of Abdo the Turk. Abdo was an attendant in a Turkish Bath. He was a man of muscle, and one day it occurred to him that he would like to earn some easy money as a pugilist. He had never done anything in that line, but he understood the general idea of the thing—you ran at your man and hit him anywhere north of the belt. The scheme looked good to Abdo. He made a match, and went into training. The night arrived, and he sat in his corner waiting for the gong to sound. Directly it sounded he leaped from his seat, at the same time putting all he knew into a right swing. There was steam behind that swing. It missed the other man by seven feet, and started Abdo spinning on his axis. The other man observed Abdo carefully for a few moments, then, as he came round for the fourth time, leaned forward and hit him under the jaw. Abdo was counted out, and retired from pugilism.

I was reminded of Abdo by some of the bouts at the

Public Schools’ Boxing Competitions this year, especially in the middleweight

division. Nobody could accuse the competitors of not trying. Their fault was

that they tried too hard and at the wrong time. They swung at a venture, and

were only saved from disaster by the fact that the other man was equally wild.

I was reminded of Abdo by some of the bouts at the

Public Schools’ Boxing Competitions this year, especially in the middleweight

division. Nobody could accuse the competitors of not trying. Their fault was

that they tried too hard and at the wrong time. They swung at a venture, and

were only saved from disaster by the fact that the other man was equally wild.

Of course, it is easy enough to lean back in one’s seat and tell boxers to be cool and collected, and I realise that one’s outlook on things is not so judicial in the ring as out of it, but this year most of the heavier boxers were wilder than they need have been.

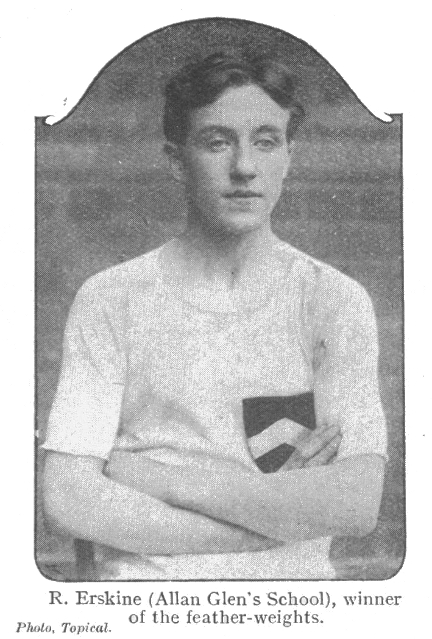

This

year’s Aldershot, however, produced one pugilistic

marvel in R. Erskine (Allan Glen’s School), quite the most scientific boxer who

has ever appeared in the Public Schools’ Championships. Two days before,

Erskine had been runner-up for the Amateur Featherweight Championship at the

Alexandra Palace, which, as men come from every country to compete, is really

the amateur championship of the world.

It was an extraordinary performance for a boy

of eighteen. His victory at Aldershot was, of course,

never in doubt, and it was rather hard luck on an unusually good lot of

feather-weights that their

year should have coincided with his.

This

year’s Aldershot, however, produced one pugilistic

marvel in R. Erskine (Allan Glen’s School), quite the most scientific boxer who

has ever appeared in the Public Schools’ Championships. Two days before,

Erskine had been runner-up for the Amateur Featherweight Championship at the

Alexandra Palace, which, as men come from every country to compete, is really

the amateur championship of the world.

It was an extraordinary performance for a boy

of eighteen. His victory at Aldershot was, of course,

never in doubt, and it was rather hard luck on an unusually good lot of

feather-weights that their

year should have coincided with his.

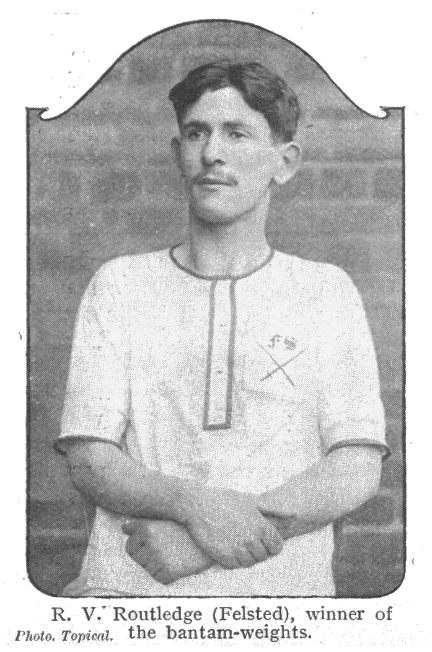

To take the results in detail, the bantam-weights fell once more to R. V. Routledge (Felsted), last year’s holder, whose superior strength and science made him a certain champion from the start. His hardest fight was with J. S. H. Morgan, of Repton. Morgan’s was one of the pluckiest displays of the day. His hurricane effort at the beginning of the second round was enthusiastically cheered, so much so that in the interval between the second and third rounds the M.C., mounting the platform, soaked it to the impulsive spectators in a neat speech. Cheering one man during a round, he very justly pointed out, was hard on the other man. The third round saw Morgan too exhausted for effective work, and Routledge, having the fight in hand, behaved like a good sportsman, and only did just enough to score points.

In

the final Routledge met A. M. MacColl

(Clifton), and beat him in the second round. MacColl,

who was smaller than his opponent, boxed prettily, but without much power. His

ducking was good, but he was not strong enough to keep Routledge

out.

In

the final Routledge met A. M. MacColl

(Clifton), and beat him in the second round. MacColl,

who was smaller than his opponent, boxed prettily, but without much power. His

ducking was good, but he was not strong enough to keep Routledge

out.

The elimination system has the drawback that it sometimes brings the wrong man into the final. On merit, Morgan should have been runner-up in the bantams.

The feathers, the best performers of the day, were also the most numerous. There were twenty-one entries, of whom, after Erskine, the pick were P. L. Roy (St. Paul’s), C. N. Lowe (Dulwich), runner-up to Routledge in last year’s bantams, J. N. Richardson (Repton), and C. N. Ratcliffe (Felsted). One always keeps an eye on the St. Paul’s man, and this year Jerry Driscoll, the king of boxing instructors, had had good material to work on in Roy. Roy keeps both hands going well, and, like most of Jerry’s pupils, understands the use of the straight left. Lowe has the shoulders of a light-weight, and carries a heavy punch in both hands. Richardson is small, but quick and excellent with his left leads. Ratcliffe is much the same on a larger scale. In any ordinary year any of these four might have won, but Erskine was in a class of his own. What was particularly noticeable about Erskine’s boxing was that he always seemed to have something in reserve. In his earlier fights he did enough to win with a comfortable margin, but no more. It was not until the final, when he met Roy, that he came anywhere near exerting himself. For the first time he forced the work and showed a new speed, and, especially with the left, a hard punch. Roy stayed out the three rounds, and, always trying, put up what, in the circumstances, was an excellent fight. His pluck was unlimited. There was, indeed, a good deal of pluck shown in the feathers, notably by Fulton (Rugby) in his bout with Lowe, and Martyn (Bedford) against Roy.

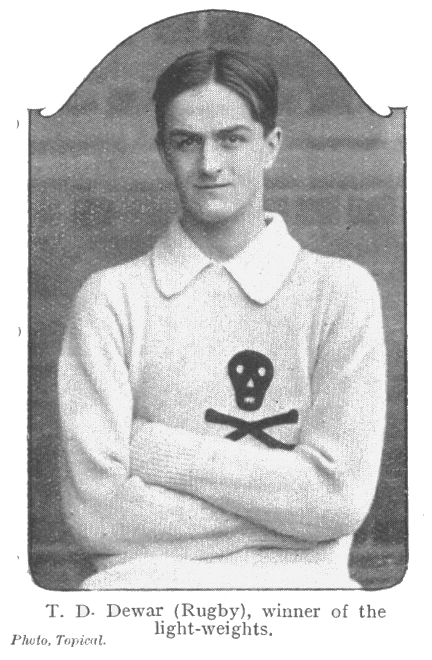

V. C. Farrell (Cranbrook), the light-weight title holder, was down on the card of entries, but, either through illness or excess of weight, did not appear. R. D. Doherty (Dulwich), who showed excellent form last year, was kept away by illness. A. J. R. Anderson (Bedford), who won the feathers in 1909, was up again, but was unexpectedly beaten in his second bout, with T. D. Dewar, of Rugby, who subsequently came out as champion. Dewar is tall, with a good reach, but has a little too much of Abdo the Turk’s methods at present to be quite satisfactory. He is very cheerful and willing about it all, and knows no fear; but an opponent with a good straight left might have had him in difficulties.

The light-weights were chiefly remarkable for sudden lapses of form. On his showing against Webster (Clifton), I had picked L. A. de Yongh (Harrow) as the 1911 champion. In that fight he was boxing excellently. When he met Montague-Marks (St. Paul’s), in the semi-final, however, he developed a quite unexpected taste for clinching. Subsequently he tried body-blows with success, but it was too late, and Marks won with something in hand. Then, again, Marks, when he met Dewar in the final, went all to pieces, and did not get through to the second round. I was sitting on the side of the ring where the fight ended, and Marks did not seem knocked out. He seemed dazed or exhausted. First, there was some scrambling work in Dewar’s corner, and then Marks fell, apparently not from any one blow. Probably a chance punch early in the rally did the real damage.

It would have been interesting to have seen more of W. J. Burt (Felsted), but after beating W. H. Hedges (Malvern) in the second series he retired from the competition. His foot-work was good, and he might have done something against Dewar. On the general run of the form, however, Dewar was the best man in the competition.

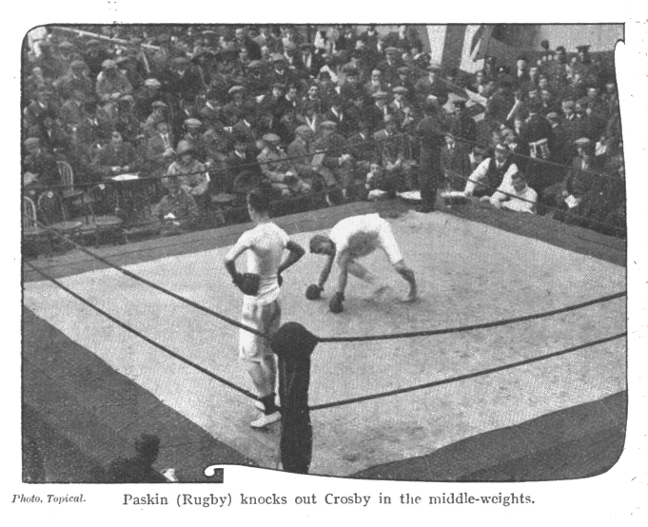

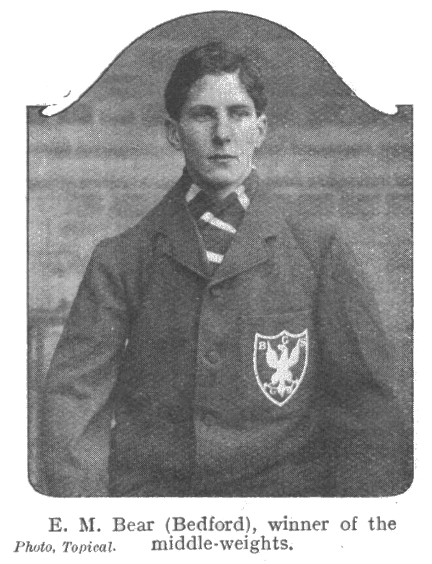

The

middle-weight competition was a mere

brawl. Everyone slogged. There was no foot-work, no ducking, no

side-stepping. Bear, of Bedford, and Rissik, of

Clifton, were a good deal the best of the entrants. Here, again, the legitimate

runner-up was kept from winning a medal by meeting the champion too soon. Bear

and Rissik met in the first series, and an excellent

fight ended in Bear just getting home. After that Bear had no difficulty. He

easily defeated Taggart (King William’s College) in the second series, and in

the final fought Paskin, of Rugby, to a standstill in

the first minute of the third round. Paskin did well

in the first round, but Bear was the stronger, and had really won before the

end of round two.

The

middle-weight competition was a mere

brawl. Everyone slogged. There was no foot-work, no ducking, no

side-stepping. Bear, of Bedford, and Rissik, of

Clifton, were a good deal the best of the entrants. Here, again, the legitimate

runner-up was kept from winning a medal by meeting the champion too soon. Bear

and Rissik met in the first series, and an excellent

fight ended in Bear just getting home. After that Bear had no difficulty. He

easily defeated Taggart (King William’s College) in the second series, and in

the final fought Paskin, of Rugby, to a standstill in

the first minute of the third round. Paskin did well

in the first round, but Bear was the stronger, and had really won before the

end of round two.

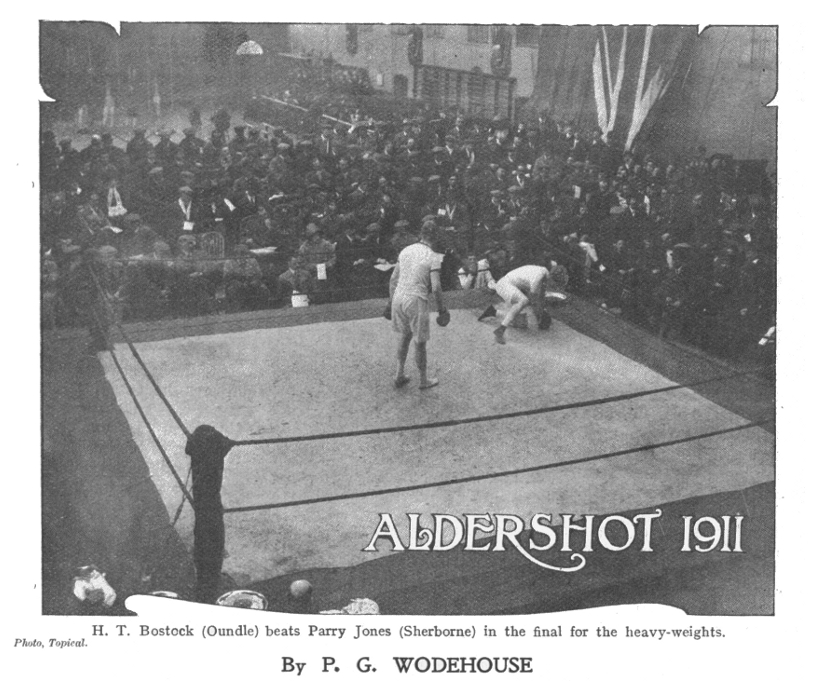

There was only one man in it in the Heavies—H. T. Bostock (Oundle). Not since F. J. V. Hopley’s time has a public-school heavy-weight champion won his title with so little effort. His first fight, with Southern (Clifton), who was runner-up in the Middles last year, was over in half a round. His second, with Norman, of St. Paul’s, only took thirty seconds. And the final, against Parry Jones, of Sherborne, was stopped in the second round. The fact that Bostock’s weight was within a pound of fourteen stone may account for these things. And he did not seem to carry any superfluous flesh. In addition to this, though his knowledge of leading was elementary, he had a good counter with both hands, and a very hard punch with his right. It is difficult to say how he would shape if extended, but I cannot recall any public-school heavy-weight, except Hopley, who would have had a chance against him.

Parry Jones deserves a good deal of credit for staying even a round and a half with him. He was giving away nineteen pounds in weight, but he fought a very game fight, and did most of the leading.

It is hard to say whether the standard of the boxing was equal to that of other years. Of the champions, Erskine is the best feather-weight champion Aldershot has seen; Bostock is better than any heavy-weight since 1902; and Routledge is probably as good a bantam as will be seen in this competition for many years. The general average of the boxing was much about the same as usual, sometimes scientific, sometimes the reverse, but always very much in earnest.

Madame Eulalie’s Rare Plums

Madame Eulalie’s Rare Plums