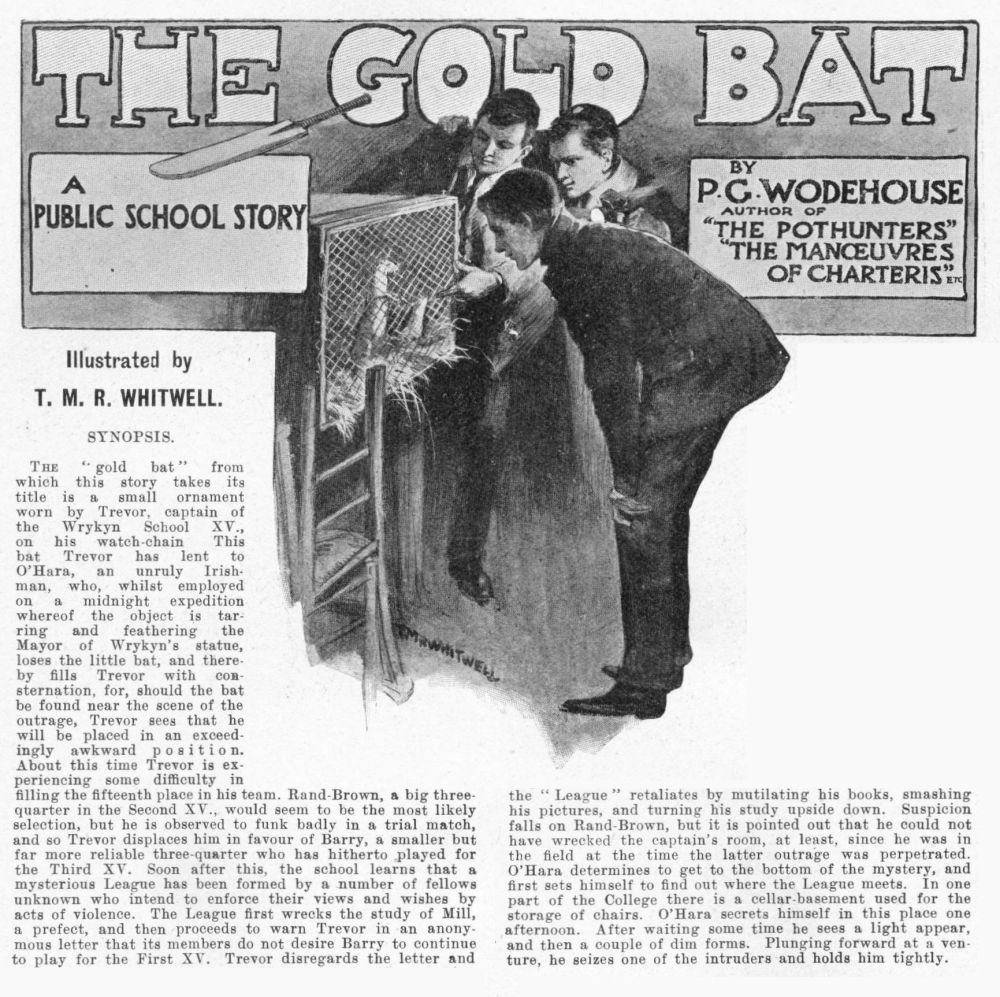

The Captain, December 1903

CHAPTER IX.

Mainly about Ferrets.

W!”

exclaimed the captive, with no uncertain voice. “Let go, you ass, you’re

hurting.”

W!”

exclaimed the captive, with no uncertain voice. “Let go, you ass, you’re

hurting.”

The voice was a treble voice. This surprised O’Hara. It looked very much as if he had put up the wrong bird. From the dimensions of the arm which he was holding, his prisoner seemed to be of tender years.

“Let go, Harvey, you idiot. I shall kick.”

Before the threat could be put into execution, O’Hara, who had been fumbling all this while in his pocket for a match, struck a light. The features of the owner of the arm—he was still holding it—were lit up for a moment.

“Why, it’s young Renford!” he exclaimed. “What are you doing down here?”

Renford, however, continued to pursue the topic of his arm, and the effect that the vice-like grip of the Irishman had had upon it.

“You’ve nearly broken it,” he said, complainingly.

“I’m sorry. I mistook you for somebody else. Who’s that with you?”

“It’s me,” said an ungrammatical voice.

“Who’s me?”

“Harvey.”

At this point a soft yellow light lit up the more immediate neighbourhood. Harvey had brought a bicycle lamp into action.

“That’s more like it,” said Renford. “Look here, O’Hara, you won’t split, will you?”

“I’m not an informer by profession, thanks,” said O’Hara.

“Oh, I know it’s all right, really, but you can’t be too careful. Because one isn’t allowed down here, and there’d be a beastly row if it got out about our being down here.”

“And they would be cobbed,” put in Harvey.

“Who are they?” asked O’Hara.

“Ferrets. Like to have a look at them?”

“Ferrets!”

“Yes. Harvey brought back a couple at the beginning of term. Ripping little beasts. We couldn’t keep them in the house, as they’d have got dropped on in a second, so we had to think of somewhere else, and thought why not keep them down here?”

“Why, indeed?” said O’Hara. “Do ye find they like it?”

“Oh, they don’t mind,” said Harvey. “We feed ’em twice a day. Once before breakfast—we take it in turns to get up early—and once directly after school. And on half-holidays and Sundays we take them out on to the downs.”

“What for?”

“Why, rabbits, of course. Renford brought back a saloon-pistol with him. We keep it locked up in a box—don’t tell any one.”

“And what do ye do with the rabbits?”

“We pot at them as they come out of the holes.”

“Yes, but when ye hit ’em?”

“Oh,” said Renford, with some reluctance, “we haven’t exactly hit any yet.”

“We’ve got jolly near, though, lots of times,” said Harvey. “Last Saturday I swear I wasn’t more than a quarter of an inch off one of them. If it had been a decent-sized rabbit, I should have plugged it middle stump; only it was a small one, so I missed. But come and see them. We keep ’em right at the other end of the place, in case anybody comes in.”

“Have you ever seen anybody down here?” asked O’Hara.

“Once,” said Renford. “Half-a-dozen chaps came down here once while we were feeding the ferrets. We waited till they’d got well in, then we nipped out quietly. They didn’t see us.”

“Did you see who they were?”

“No. It was too dark. Here they are. Rummy old crib this, isn’t it? Look out for your shins on the chairs. Switch on the light, Harvey. There, aren’t they rippers? Quite tame, too. They know us quite well. They know they’re going to be fed, too. Hullo, Sir Nigel! This is Sir Nigel. Out of the ‘White Company,’ you know. Don’t let him nip your fingers. This other one’s Sherlock Holmes.”

“Cats-s-s--s!!” said O’Hara. He had a sort of idea that that was the right thing to say to any animal that could chase and bite.

Renford was delighted to be able to show his ferrets off to so distinguished a visitor.

“What were you down here about?” inquired Harvey, when the little animals had had their meal and had retired once more into private life.

O’Hara had expected this question, but he did not quite know what answer to give. Perhaps, on the whole, he thought, it would be best to tell them the real reason. If he refused to explain, their curiosity would be roused, which would be fatal. And to give any reason except the true one called for a display of impromptu invention of which he was not capable. Besides, they would not be likely to give away his secret while he held this one of theirs connected with the ferrets. He explained the situation briefly, and swore them to silence on the subject.

Renford’s comment was brief.

“Golly!” he observed.

Harvey went more deeply into the question.

“What makes you think they meet down here?” he asked.

“I saw some fellows cutting out of here last night. And you say ye’ve seen them here, too. I don’t see what object they could have down here if they weren’t the League holding a meeting. I don’t see what else a chap would be after.”

“He might be keeping ferrets,” hazarded Renford.

“The whole school doesn’t keep ferrets,” said O’Hara. “You’re unique in that way. No, it must be the League, an’ I mean to wait here till they come.”

“Not all night?” asked Harvey. He had a great respect for O’Hara, whose reputation in the school for out-of-the-way doings was considerable. In the bright lexicon of O’Hara he believed there to be no such word as “impossible.”

“No,” said O’Hara, “but till lock-up. You two had better cut now.”

“Yes, I think we’d better,” said Harvey.

“And don’t ye breathe a word about this to a soul”—a warning which extracted fervent promises of silence from both youths.

“This,” said Harvey, as they emerged on to the gravel, “is something like. I’m jolly glad we’re in it.”

“Rather. Do you think O’Hara will catch them?”

“He must if he waits down there long enough. They’re certain to come again. Don’t you wish you’d been here when the League was on before?”

“I should think I did. Race you over to the shop. I want to get something before it shuts.”

“Right O!” And they disappeared.

O’Hara waited where he was till six struck from the clock-tower, followed by the sound of the bell as it rang for lock-up. Then he picked his way carefully through the groves of chairs, barking his shins now and then on their out-turned legs, and, pushing open the door, went out into the open air. It felt very fresh and pleasant after the brand of atmosphere supplied in the vault. He then ran over to the gymnasium to meet Moriarty, feeling a little disgusted at the lack of success that had attended his detective efforts up to the present. So far he had nothing to show for his trouble except a good deal of dust on his clothes, and a dirty collar. But he was full of determination. He could play a waiting game.

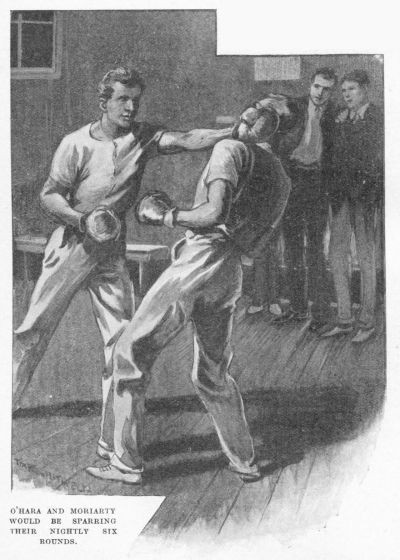

It was a pity, as it happened, that O’Hara left the vault when he did. Five minutes after he had gone, six shadowy forms made their way silently and in single file through the doorway of the vault, which they closed carefully behind them. The fact that it was after lock-up was of small consequence. A good deal of latitude in that way was allowed at Wrykyn. It was the custom to go out, after the bell had sounded, to visit the gymnasium. In the winter and Easter terms, the gymnasium became a sort of social club. People went there with a very small intention of doing gymnastics. They went to lounge about, talking to cronies, in front of the two huge stoves which warmed the place. Occasionally, as a concession to the look of the thing, they would do an easy exercise or two on the horse or parallels, but, for the most part, they preferred the rôle of spectator. There was plenty to see. In one corner O’Hara and Moriarty would be sparring their nightly six rounds (in two batches of three rounds each). In another, Drummond, who was going up to Aldershot as a feather-weight, would be putting in a little practice with the instructor. On the apparatus, the members of the gymnastic six, including the two experts who were to carry the school colours to Aldershot in the spring, would be performing their usual marvels. It was worth dropping into the gymnasium of an evening. In no other place in the school were so many sights to be seen.

When you were surfeited with sight-seeing, you went off to your house. And this was where the peculiar beauty of the gymnasium system came in. You went up to any master who happened to be there—there was always one at least—and observed in suave accents, “Please, sir, can I have a paper?” Whereupon, he, taking a scrap of paper, would write upon it, “J. O. Jones (or A. B. Smith or C. D. Robinson) left gymnasium at such-and-such a time.” And, by presenting this to the menial who opened the door to you at your house, you went in rejoicing, and all was peace.

Now, there was no mention on the paper of the hour at which you came to the gymnasium—only of the hour at which you left. Consequently, certain lawless spirits would range the neighbourhood after lock-up, and, by putting in a quarter of an hour at the gymnasium before returning to their houses, escape comment. To this class belonged the shadowy forms previously mentioned.

O’Hara had forgotten this custom, with the result that he was not at the vault when they arrived. Moriarty, to whom he confided between the rounds the substance of his evening’s discoveries, reminded him of it.

“It’s no good watching before lock-up,” he said. “After six is the time they’ll come, if they come at all.”

“Bedad, ye’re right,” said O’Hara. “One of these nights we’ll take a night off from boxing, and go and watch.”

“Right,” said Moriarty. “Are ye ready to go on?”

“Yes. I’m going to practise that left swing at the body this round. The one Fitzsimmons does.” And they “put ’em up” once more.

CHAPTER X.

Being a Chapter of Accidents.

N

the evening following O’Hara’s adventure in the vaults, Barry and McTodd were

in their study, getting out the tea-things. Most Wrykinians brewed in the

winter and Easter terms, when the days were short and lock-up early. In

the summer term there were other things to do—nets, which lasted till a

quarter to seven (when lock-up was), and the baths—and brewing practically

ceased. But just now it was at its height, and every evening, at a

quarter past five, there might be heard in the houses the sizzling of the

succulent sausage and other rare delicacies. As a rule, one or two

studies would club together to brew, instead of preparing solitary

banquets. This was found both more convivial and more economical.

At Seymour’s, studies numbers five, six, and seven had always combined from

time immemorial, and Barry, on obtaining study six, had carried on the

tradition. In study five were Drummond and his friend De Bertini.

In study seven, which was a smaller room and only capable of holding one person

with any comfort, one James Rupert Leather-Twigg (that was his singular name,

as Mr. Gilbert has it) had taken up his abode. The name of Leather-Twigg

having proved, at an early date in his career, too great a mouthful for Wrykyn,

he was known to his friends and acquaintances by the euphonious title of

Shoeblossom. The charm about the genial Shoeblossom was that you could

never tell what he was going to do next. All that you could rely on with

any certainty was that it would be something which would have been better left

undone.

N

the evening following O’Hara’s adventure in the vaults, Barry and McTodd were

in their study, getting out the tea-things. Most Wrykinians brewed in the

winter and Easter terms, when the days were short and lock-up early. In

the summer term there were other things to do—nets, which lasted till a

quarter to seven (when lock-up was), and the baths—and brewing practically

ceased. But just now it was at its height, and every evening, at a

quarter past five, there might be heard in the houses the sizzling of the

succulent sausage and other rare delicacies. As a rule, one or two

studies would club together to brew, instead of preparing solitary

banquets. This was found both more convivial and more economical.

At Seymour’s, studies numbers five, six, and seven had always combined from

time immemorial, and Barry, on obtaining study six, had carried on the

tradition. In study five were Drummond and his friend De Bertini.

In study seven, which was a smaller room and only capable of holding one person

with any comfort, one James Rupert Leather-Twigg (that was his singular name,

as Mr. Gilbert has it) had taken up his abode. The name of Leather-Twigg

having proved, at an early date in his career, too great a mouthful for Wrykyn,

he was known to his friends and acquaintances by the euphonious title of

Shoeblossom. The charm about the genial Shoeblossom was that you could

never tell what he was going to do next. All that you could rely on with

any certainty was that it would be something which would have been better left

undone.

It was just five o’clock when Barry and McTodd started to get things ready. They were not high enough up in the school to have fags, so that they had to do this for themselves.

Barry was still in football clothes. He had been out running and passing with the first fifteen. McTodd, whose idea of exercise was winding up a watch, had been spending his time since school ceased in the study with a book. He was in his ordinary clothes. It was therefore fortunate that, when he upset the kettle (he nearly always did at some period of the evening’s business), the contents spread themselves over Barry, and not over himself. Football clothes will stand any amount of water, whereas McTodd’s “Youth’s winter suiting at forty-two shillings and sixpence,” might have been injured. Barry, however, did not look upon the episode in this philosophical light. He spoke to him eloquently for a while, and then sent him downstairs to fetch more water. While he was away, Drummond and De Bertini came in.

“Hullo,” said Drummond, “tea ready?”

“Not much,” replied Barry, bitterly, “not likely to be, either, at this rate. We’d just got the kettle going when that ass McTodd plunged against the table and upset the lot over my bags. Lucky the beastly stuff wasn’t boiling. I’m soaked.”

“While we wait—the sausages—Yes?—a good idea—McTodd, he is downstairs—but to wait? No, no. Let us. Shall we? Is it not so? Yes?” observed Bertie, lucidly.

“Now construe,” said Barry, looking at the linguist with a bewildered expression. It was a source of no little inconvenience to his friends that De Bertini was so very fixed in his determination to speak English. He was a trier all the way, was De Bertini. You rarely caught him helping out his remarks with the language of his native land. It was English or nothing with him. To most of his circle it might as well have been Zulu.

Drummond, either through natural genius or because he spent more time with him, was generally able to act as interpreter. Occasionally there would come a linguistic effort by which even he freely confessed himself baffled, and then they would pass on unsatisfied. But, as a rule, he was equal to the emergency. He was so now.

“What Bertie means,” he explained, “is that it’s no good us waiting for McTodd to come back. He never could fill a kettle in less than ten minutes, and even then he’s certain to spill it coming upstairs and have to go back again. Let’s get on with the sausages.”

The pan had just been placed on the fire when McTodd returned with the water. He tripped over the mat as he entered, and spilt about half a pint into one of his football boots, which stood inside the door, but the accident was comparatively trivial, and excited no remark.

“I wonder where that slacker Shoeblossom has got to,” said Barry. “He never turns up in time to do any work. He seems to regard himself as a beastly guest. I wish we could finish the sausages before he comes. It would be a sell for him.”

“Not much chance of that,” said Drummond, who was kneeling before the fire and keeping an excited eye on the spluttering pan, “you see. He’ll come just as we’ve finished cooking them. I believe the man waits outside with his ear to the keyhole. Hullo! Stand by with the plate. They’ll be done in half a jiffy.”

Just as the last sausage was deposited in safety on the plate, the door opened, and Shoeblossom, looking as if he had not brushed his hair since early childhood, sidled in with an attempt at an easy nonchalance which was rendered quite impossible by the hopeless state of his conscience.

“Ah,” he said, “brewing, I see. Can I be of any use?”

“We’ve finished years ago,” said Barry.

“Ages ago,” said McTodd.

A look of intense alarm appeared on Shoeblossom’s classical features.

“You’ve not finished, really?”

“We’ve finished cooking everything,” said Drummond. “We haven’t begun tea yet. Now, are you happy?”

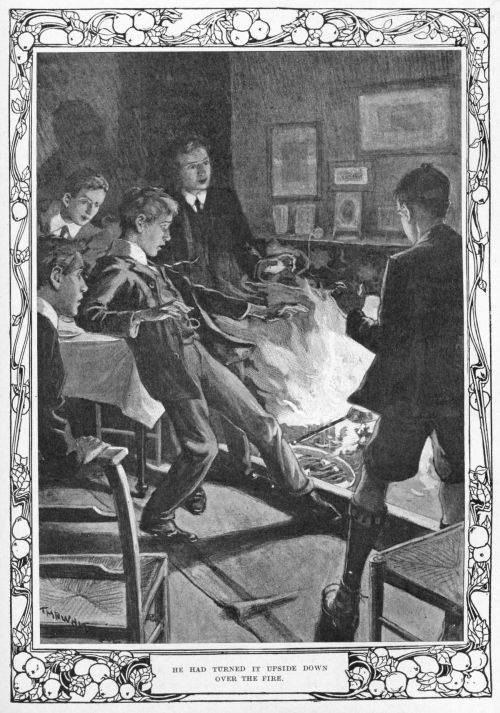

Shoeblossom was. So happy that he felt he must do something to celebrate the occasion. He felt like a successful general. There must be something he could do to show that he regarded the situation with approval. He looked round the study. Ha! Happy thought—the frying-pan. That useful culinary instrument was lying in the fender, still bearing its cargo of fat, and beside it—a sight to stir the blood and make the heart beat faster—were the sausages, piled up on their plate.

Shoeblossom stooped. He seized the frying-pan. He gave it one twirl in the air. Then, before any one could stop him, he had turned it upside down over the fire. As has been already remarked, you could never predict exactly what James Rupert Leather-Twigg would be up to next.

When anything goes out of the frying-pan into the fire, it is usually productive of interesting by-products. The maxim applies to fat. The fat was in the fire with a vengeance. A great sheet of flame rushed out and up. Shoeblossom leaped back with a readiness highly creditable in one who was not a professional acrobat. The covering of the mantelpiece caught fire. The flames went roaring up the chimney.

Drummond, cool while everything else was so hot, without a word moved to the mantelpiece to beat out the fire with a football shirt. Bertie was talking rapidly to himself in French. Nobody could understand what he was saying, which was possibly fortunate.

By the time Drummond had extinguished the mantelpiece, Barry had also done good work by knocking the fire into the grate with the poker. McTodd, who had been standing up till now in the far corner of the room, gaping vaguely at things in general, now came into action. Probably it was force of habit that suggested to him that the time had come to upset the kettle. At any rate, upset it he did—most of it over the glowing, blazing mass in the grate, the rest over Barry. One of the largest and most detestable smells the study had ever had to endure instantly assailed their nostrils. The fire in the study was out now, but in the chimney it still blazed merrily.

“Go up on to the roof and heave water down,” said Drummond, the strategist. “You can get out from Milton’s dormitory window. And take care not to chuck it down the wrong chimney.”

Barry was starting for the door to carry out these excellent instructions, when it flew open.

“Pah! What have you boys been doing? What an abominable smell. Pah!” said a muffled voice. It was Mr. Seymour. Most of his face was concealed in a large handkerchief, but by the look of his eyes, which appeared above, he did not seem pleased. He took in the situation at a glance. Fires in the house were not rarities. One facetious sportsman had once made a rule of setting the senior day-room chimney on fire every term. He had since left (by request), but fires still occurred.

“Is the chimney on fire?”

“Yes, sir,” said Drummond.

“Go and find Herbert, and tell him to take some water on to the roof and throw it down.” Herbert was the boot and knife cleaner at Seymour’s.

Barry went. Soon afterwards a splash of water in the grate announced that the intrepid Herbert was hard at it. Another followed, and another. Then there was a pause. Mr. Seymour thought he would look up to see if the fire was out. He stooped and peered into the darkness, and, even as he gazed, splash came the contents of the fourth pail, together with some soot with which they had formed a travelling acquaintance on the way down. Mr. Seymour staggered back, grimy and dripping. There was dead silence in the study. Shoeblossom’s face might have been seen working convulsively.

The silence was broken by a hollow, sepulchral voice with a strong Cockney accent.

“Did yer see any water come down then, sir?” said the voice.

Shoeblossom collapsed into a chair, and began to sob feebly.

* * * * * * *

“——disgraceful . . . scandalous . . . get up, Leather-Twigg . . . not to be trusted . . . babies . . . three hundred lines, Leather-Twigg. . . . abominable . . . surprised . . . ought to be ashamed of yourselves . . . double, Leather-Twigg . . . not fit to have studies . . . atrocious . . .——”

Such were the main heads of Mr. Seymour’s speech on the situation as he dabbed desperately at the soot on his face with his handkerchief. Shoeblossom stood and gurgled throughout. Not even the thought of six hundred lines could quench that dauntless spirit.

“Finally,” perorated Mr. Seymour, as he was leaving the room, “as you are evidently not to be trusted with rooms of your own, I forbid you to enter them till further notice. It is disgraceful that such a thing should happen. Do you hear, Barry? And you, Drummond? You are not to enter your studies again till I give you leave. Move your books down to the senior day-room tonight.”

And Mr. Seymour stalked off to clean himself.

CHAPTER XI.

The House Matches.

T

was something of a consolation to Barry and his friends—at any rate, to Barry

and Drummond—that directly after they had been evicted from their study, the

house-matches began. Except for the Ripton match, the house-matches were

the most important event of the Easter term. Even the sports at the

beginning of April were productive of less excitement. There were twelve

houses at Wrykyn, and they played on the “knocking-out” system. To be

beaten once meant that a house was no longer eligible for the

competition. It could play “friendlies” as much as it liked, but, play it

never so wisely, it could not lift the cup. Thus it often happened that a

weak house, by fluking a victory over a strong rival, found itself, much to its

surprise, in the semi-final, or sometimes even in the final. This was

rarer at football than at cricket, for at football the better team generally wins.

T

was something of a consolation to Barry and his friends—at any rate, to Barry

and Drummond—that directly after they had been evicted from their study, the

house-matches began. Except for the Ripton match, the house-matches were

the most important event of the Easter term. Even the sports at the

beginning of April were productive of less excitement. There were twelve

houses at Wrykyn, and they played on the “knocking-out” system. To be

beaten once meant that a house was no longer eligible for the

competition. It could play “friendlies” as much as it liked, but, play it

never so wisely, it could not lift the cup. Thus it often happened that a

weak house, by fluking a victory over a strong rival, found itself, much to its

surprise, in the semi-final, or sometimes even in the final. This was

rarer at football than at cricket, for at football the better team generally wins.

The favourites this year were Donaldson’s, though some fancied Seymour’s. Donaldson’s had Trevor, whose leadership was worth almost more than his play. In no other house was training so rigid. You could tell a Donaldson’s man, if he was in his house-team, at a glance. If you saw a man eating oatmeal biscuits in the shop, and eyeing wistfully the while the stacks of buns and pastry, you could put him down as a Donaldsonite without further evidence. The captains of the other houses used to prescribe a certain amount of self-abnegation in the matter of food, but Trevor left his men barely enough to support life—enough, that is, of the things that are really worth eating. The consequence was that Donaldson’s would turn out for an important match all muscle and bone, and on such occasions it was bad for those of their opponents who had been taking life more easily. Besides Trevor they had Clowes, and had had bad luck in not having Paget. Had Paget stopped, no other house could have looked at them. But by his departure, the strength of the team had become more nearly on a level with that of Seymour’s.

Some even thought that Seymour’s were the stronger. Milton was as good a forward as the school possessed. Besides him there were Barry and Rand-Brown on the wings. Drummond was a useful half, and five of the pack had either first or second fifteen colours. It was a team that would take some beating.

Trevor came to that conclusion early. “If we can beat Seymour’s, we’ll lift the cup,” he said to Clowes.

“We’ll have to do all we know,” was Clowes’ reply.

They were watching Seymour’s pile up an immense score against a scratch team got up by one of the masters. The first round of the competition was over. Donaldson’s had beaten Templar’s, Seymour’s the School House. Templar’s were rather stronger than the School House, and Donaldson’s had beaten them by a rather larger score than that which Seymour’s had run up in their match. But neither Trevor nor Clowes was inclined to draw any augury from this. Seymour’s had taken things easily after half-time; Donaldson’s had kept going hard all through.

“That makes Rand-Brown’s fourth try,” said Clowes, as the wing three-quarter of the second fifteen raced round and scored in the corner.

“Yes. This is the sort of game he’s all right in. The man who’s marking him is no good. Barry’s scored twice, and both good tries, too.”

“Oh, there’s no doubt which is the best man,” said Clowes. “I only mentioned that it was Rand-Brown’s fourth as an item of interest.”

The game continued. Barry scored a third try.

“We’re drawn against Appleby’s next round,” said Trevor. “We can manage them all right.”

“When is it?”

“Next Thursday. Nomads’ match on Saturday. Then Ripton, Saturday week.”

“Who’ve Seymour’s drawn?”

“Day’s. It’ll be a good game, too. Seymour’s ought to win, but they’ll have to play their best. Day’s have got some good men.”

“Fine scrum,” said Clowes.

“Yes. Quick in the open, too, which is always good business. I wish they’d beat Seymour’s.”

“Oh, we ought to be all right, whichever wins.”

Appleby’s did not offer any very serious resistance to the Donaldson attack. They were outplayed at every point of the game, and, before half-time, Donaldson’s had scored their thirty points. It was a rule in all in-school matches—and a good rule, too—that, when one side led by thirty points, the match stopped. This prevented those massacres which do so much towards crushing all the football out of the members of the beaten team; and it kept the winning team from getting slack, by urging them on to score their thirty points before half-time. There were some houses—notoriously slack—which would go for a couple of seasons without ever playing the second half of a match.

Having polished off the men of Appleby, the Donaldson team trooped off to the other game to see how Seymour’s were getting on with Day’s. It was evidently an exciting match. The first half had been played to the accompaniment of much shouting from the ropes. Though coming so early in the competition, it was really the semi-final, for whichever team won would be almost certain to get into the final. The school had turned up in large numbers to watch.

“Seymour’s looking tired of life,” said Clowes. “That would seem as if his fellows weren’t doing well.”

“What’s been happening here?” asked Trevor of an enthusiast in a Seymour’s house cap whose face was crimson with yelling.

“One goal all,” replied the enthusiast huskily. “Did you beat Appleby’s?”

“Yes. Thirty points before half-time. Who’s been doing the scoring here?”

“Milton got in for us. He barged through out of touch. We’ve been pressing the whole time. Barry got over once, but he was held up. Hullo, they’re beginning again. Buck up, Sey-mour’s.”

His voice cracking on the high note, he took an immense slab of vanilla chocolate as a remedy for hoarseness.

“Who scored for Day’s?” asked Clowes.

“Strachan. Rand-Brown let him through from their twenty-five. You never saw anything so rotten as Rand-Brown. He doesn’t take his passes, and Strachan gets past him every time.”

“Is Strachan playing on the wing?”

Strachan was the first fifteen full-back.

“Yes. They’ve put young Bassett back instead of him. Sey-mour’s. Buck up, Seymour’s. We-ell played! There, did you ever see anything like it?” he broke off disgustedly.

The Seymourite playing centre next to Rand-Brown had run through to the back and passed out to his wing, as a good centre should. It was a perfect pass, except that it came at his head instead of his chest. Nobody with any pretensions to decent play should have missed it. Rand-Brown, however, achieved that feat. The ball struck his hands and bounded forward. The referee blew his whistle for a scrum, and a certain try was lost.

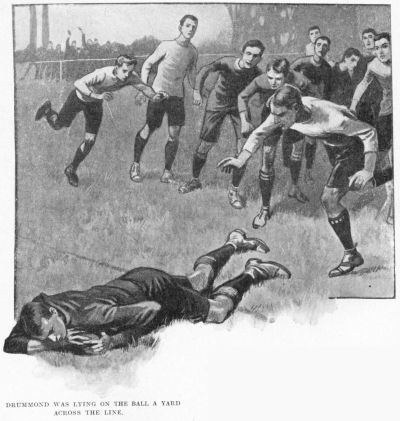

From the scrum the Seymour’s forwards broke away to the goal-line, where they were pulled up by Bassett. The next minute the defence had been pierced, and Drummond was lying on the ball a yard across the line. The enthusiast standing by Clowes expended the last relics of his voice in commemorating the fact that his side had the lead.

“Drummond’ll be good next year,” said Trevor. And he made a mental note to tell Allardyce, who would succeed him in the command of the school football, to keep an eye on the player in question.

The triumph of the Seymourites was not long-lived. Milton failed to convert Drummond’s try. From the drop-out from the twenty-five line Barry got the ball, and punted into touch. The throw-out was not straight, and a scrum was formed. The ball came out to the Day’s halves, and went across to Strachan. Rand-Brown hesitated, and then made a futile spring at the first fifteen man’s neck. Strachan handed him off easily, and ran. The Seymour’s full-back, who was a poor player, failed to get across in time. Strachan ran round behind the posts, the kick succeeded, and Day’s now led by two points.

After this the game continued in Day’s half. Five minutes before time was up, Drummond got the ball from a scrum nearly on the line, passed it to Barry on the wing instead of opening up the game by passing to his centres, and Barry slipped through in the corner. This put Seymour’s just one point ahead, and there they stayed till the whistle blew for no-side.

Milton walked over to the boarding-houses with Clowes and Trevor. He was full of the match, particularly of the iniquity of Rand-Brown. “I slanged him on the field,” he said. “It’s a thing I don’t often do, but what else can you do when a man plays like that? He lost us three certain tries.”

“When did you administer your rebuke?” inquired Clowes.

“When he had let Strachan through that second time, in the second half. I asked him why on earth he tried to play footer at all. I told him a good kiss-in-the-ring club was about his form. It was rather cheap, but I felt so frightfully sick about it. It’s sickening to be let down like that when you’ve been pressing the whole time, and ought to be scoring every other minute.”

“What had he to say on the subject?” asked Clowes.

“Oh, he gassed a bit until I told him I’d kick him if he said another word. That shut him up.”

“You ought to have kicked him. You want all the kicking practice you can get. I never saw anything feebler than that shot of yours after Drummond’s try.”

“I’d like to see you take a kick like that. It was nearly on the touch-line. Still, when we play you, we sha’n’t need to convert any of our tries. We’ll get our thirty points without that. Perhaps you’d like to scratch?”

“As a matter of fact,” said Clowes confidentially, “I am going to score seven tries against you off my own bat. You’ll be sorry you ever turned out when we’ve finished with you.”

CHAPTER XII.

News of the Gold Bat.

HOEBLOSSOM

sat disconsolately on the table in the senior day-room. He was not happy

in exile. Brewing in the senior day-room was a mere vulgar brawl, lacking

all the refining influences of the study. You had to fight for a place at

the fire, and when you had got it ’twas not always easy to keep it. And there

was no privacy. And the fellows were always bear-fighting, so that it was

impossible to read a book quietly for ten consecutive minutes without some ass

heaving a cushion at you or turning out the gas. Altogether Shoeblossom

yearned for the peace of his study, and wished earnestly that Mr. Seymour would

withdraw the order of banishment. It was the not being able to read that

he objected to chiefly. In place of brewing, the ex-proprietors of

studies five, six, and seven, now made a practice of going to the school

shop. It was more expensive and not nearly so comfortable—there is a

romance about a study brew which you can never get anywhere else—but it

served, and it was not on this score that he grumbled most. What he hated

was having to live in a bear-garden. For Shoeblossom was a man of

moods. Give him two or three congenial spirits to back him up, and he

would lead the revels with the abandon of a Mr. Bultitude (after his

return to his original form). But he liked to choose his accomplices, and

the gay sparks of the senior day-room did not appeal to him. They were

not intellectual enough. In his lucid intervals, he was accustomed to be

almost abnormally solemn and respectable. When not promoting some unholy

rag, Shoeblossom resembled an elderly gentleman of studious habits. He

liked to sit in a comfortable chair, and read a book. It was the

impossibility of doing this in the senior day-room that led him to try and

think of some other haven where he might rest. Had it been summer, he

would have taken some literature out on to the cricket-field or the downs, and

put in a little steady reading there, with the aid of a bag of cherries.

But with the thermometer low, that was impossible.

HOEBLOSSOM

sat disconsolately on the table in the senior day-room. He was not happy

in exile. Brewing in the senior day-room was a mere vulgar brawl, lacking

all the refining influences of the study. You had to fight for a place at

the fire, and when you had got it ’twas not always easy to keep it. And there

was no privacy. And the fellows were always bear-fighting, so that it was

impossible to read a book quietly for ten consecutive minutes without some ass

heaving a cushion at you or turning out the gas. Altogether Shoeblossom

yearned for the peace of his study, and wished earnestly that Mr. Seymour would

withdraw the order of banishment. It was the not being able to read that

he objected to chiefly. In place of brewing, the ex-proprietors of

studies five, six, and seven, now made a practice of going to the school

shop. It was more expensive and not nearly so comfortable—there is a

romance about a study brew which you can never get anywhere else—but it

served, and it was not on this score that he grumbled most. What he hated

was having to live in a bear-garden. For Shoeblossom was a man of

moods. Give him two or three congenial spirits to back him up, and he

would lead the revels with the abandon of a Mr. Bultitude (after his

return to his original form). But he liked to choose his accomplices, and

the gay sparks of the senior day-room did not appeal to him. They were

not intellectual enough. In his lucid intervals, he was accustomed to be

almost abnormally solemn and respectable. When not promoting some unholy

rag, Shoeblossom resembled an elderly gentleman of studious habits. He

liked to sit in a comfortable chair, and read a book. It was the

impossibility of doing this in the senior day-room that led him to try and

think of some other haven where he might rest. Had it been summer, he

would have taken some literature out on to the cricket-field or the downs, and

put in a little steady reading there, with the aid of a bag of cherries.

But with the thermometer low, that was impossible.

He felt very lonely and dismal. He was not a man with many friends. In fact, Barry and the other three were almost the only members of the house with whom he was on speaking-terms. And of these four he saw very little. Drummond and Barry were always out of doors or over at the gymnasium, and as for McTodd and De Bertini, it was not worth while talking to the one, and impossible to talk to the other. No wonder Shoeblossom felt dull. Once Barry and Drummond had taken him over to the gymnasium with them, but this had bored him worse than ever. They had been hard at it all the time—for, unlike a good many of the school, they went to the gymnasium for business, not to lounge—and he had had to sit about watching them. And watching gymnastics was one of the things he most loathed. Since then he had refused to go.

That night matters came to a head. Just as he had settled down to read, somebody, in flinging a cushion across the room, brought down the gas apparatus with a run, and before light was once more restored it was tea-time. After that there was preparation, which lasted for two hours, and by the time he had to go to bed he had not been able to read a single page of the enthralling work with which he was at present occupied.

He had just got into bed when he was struck with a brilliant idea. Why waste the precious hours in sleep? What was that saying of somebody’s, “Five hours for a wise man, six for somebody else—he forgot whom—eight for a fool, nine for an idiot,” or words to that effect? Five hours sleep would mean that he need not go to bed till half past two. In the meanwhile he could be finding out exactly what the hero did do when he found out (to his horror) that it was his cousin Jasper who had really killed the old gentleman in the wood. The only question was—how was he to do his reading? Prefects were allowed to work on after lights out in their dormitories by the aid of a candle, but to the ordinary mortal this was forbidden.

Then he was struck with another brilliant idea. It is a curious thing about ideas. You do not get one for over a month, and then there comes a rush of them, all brilliant. Why, he thought, should he not go and read in his study with a dark lantern? He had a dark lantern. It was one of the things he had found lying about at home on the last day of the holidays, and had brought with him to school. It was his custom to go about the house just before the holidays ended, snapping up unconsidered trifles which might or might not come in useful. This term he had brought back a curious metal vase (which looked Indian, but which had probably been made in Birmingham the year before last), two old coins (of no mortal use to anybody in the world, including himself), and the dark lantern. It was reposing now in the cupboard in his study nearest the window.

He had brought his book up with him on coming to bed, on the chance that he might have time to read a page or two if he woke up early. (He had always been doubtful about that man Jasper. For one thing, he had been seen pawning the old gentleman’s watch on the afternoon of the murder, which was a suspicious circumstance, and then he was not a nice character at all, and just the sort of man who would be likely to murder old gentlemen in woods.) He waited till Mr. Seymour had paid his nightly visit—he went the round of the dormitories at about eleven—and then he chuckled gently. If Mill, the dormitory prefect, was awake, the chuckle would make him speak, for Mill was of a suspicious nature, and believed that it was only his unintermitted vigilance which prevented the dormitory ragging all night.

Mill was awake.

“Be quiet, there,” he growled. “Shut up that noise.”

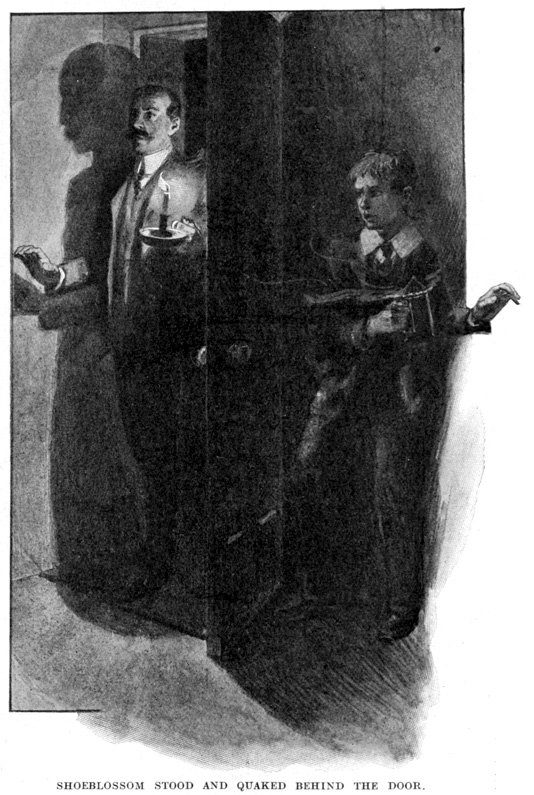

Shoeblossom felt that the time was not yet ripe for his departure. Half an hour later he tried again. There was no rebuke. To make certain he emitted a second chuckle, replete with sinister meaning. A slight snore came from the direction of Mill’s bed. Shoeblossom crept out of the room, and hurried to his study. The door was not locked, for Mr. Seymour had relied on his commands being sufficient to keep the owner out of it. He slipped in, found and lit the dark lantern, and settled down to read. He read with feverish excitement. The thing was, you see, that though Claud Trevelyan (that was the hero) knew jolly well that it was Jasper who had done the murder, the police didn’t, and, as he (Claud) was too noble to tell them, he had himself been arrested on suspicion. Shoeblossom was skimming through the pages with starting eyes, when suddenly his attention was taken from his book by a sound. It was a footstep. Somebody was coming down the passage, and under the door filtered a thin stream of light. To snap the dark slide over the lantern and dart to the door, so that if it opened he would be behind it, was with him, as Mr. Claud Trevelyan might have remarked, the work of a moment. He heard the door of study number five flung open, and then the footsteps passed on, and stopped opposite his own den. The handle turned, and the light of a candle flashed into the room, to be extinguished instantly as the draught of the moving door caught it.

Shoeblossom heard his visitor utter an exclamation of annoyance, and fumble in his pocket for matches. He recognised the voice. It was Mr. Seymour’s. The fact was that Mr. Seymour had had the same experience as General Stanley in The Pirates of Penzance:—

“The

man who finds his conscience ache,

No peace at all enjoys;

And, as I lay in bed awake,

I thought I heard a noise.”

Whether Mr. Seymour’s conscience ached or not, cannot, of course, be discovered. But he had certainly thought he heard a noise, and he had come to investigate.

The search for matches had so far proved fruitless. Shoeblossom stood and quaked behind the door. The reek of hot tin from the dark lantern grew worse momentarily. Mr. Seymour sniffed several times, until Shoeblossom thought that he must be discovered. Then, to his immense relief, the master walked away. Shoeblossom’s chance had come. Mr. Seymour had probably gone to get some matches to relight his candle. It was far from likely that the episode was closed. He would be back again presently. If Shoeblossom was going to escape, he must do it now, so he waited till the footsteps had passed away, and then darted out in the direction of his dormitory.

As he was passing Milton’s study, a white figure glided out of it. All that he had ever read or heard of spectres rushed into Shoeblossom’s petrified brain. He wished he was safely in bed. He wished he had never come out of it. He wished he had led a better and nobler life. He wished he had never been born.

The figure passed quite close to him as he stood glued against the wall, and he saw it disappear into the dormitory opposite his own, of which Rigby was prefect. He blushed hotly at the thought of the fright he had been in. It was only somebody playing the same game as himself.

He jumped into bed and lay down, having first plunged the lantern bodily into his jug to extinguish it. Its indignant hiss had scarcely died away when Mr Seymour appeared at the door. It had occurred to Mr. Seymour that he had smelt something very much out of the ordinary in Shoeblossom’s study, a smell uncommonly like that of hot tin. And a suspicion dawned on him that Shoeblossom had been in there with a dark lantern. He had come to the dormitory to confirm his suspicions. But a glance showed him how unjust they had been. There was Shoeblossom fast asleep. Mr. Seymour therefore followed the excellent example of my Lord Tomnoddy on a celebrated occasion, and went off to bed.

It was the custom for the captain of football at Wrykyn to select and publish the team for the Ripton match a week before the day on which it was to be played. On the evening after the Nomads’ match, Trevor was sitting in his study writing out the names, when there came a knock at the door, and his fag entered with a letter.

“This has just come, Trevor,” he said.

“All right. Put it down.”

The fag left the room. Trevor picked up the letter. The handwriting was strange to him. The words had been printed. Then it flashed upon him that he had received a letter once before addressed in the same way—the letter from the League about Barry. Was this, too, from that address? He opened it.

It was.

He read it, and gasped. The worst had happened. The gold bat was in the hands of the enemy.

(To be continued.)

Madame Eulalie’s Rare Plums

Madame Eulalie’s Rare Plums