The Captain, December 1904

—————

CHAPTER IX.

the sensations of an exile.

HAT!”

shouted Kennedy.

HAT!”

shouted Kennedy.

He sprang to his feet as if he had had an electric shock.

Jimmy Silver, having satisfied his passion for the dramatic by the abruptness with which he had exploded his mine, now felt himself at liberty to be sympathetic.

“It’s quite true,” he said. “And that’s just how I felt when Blackburn told me. Blackburn’s as sick as anything. Naturally he doesn’t see the point of handing you over to Kay. But the Old Man insisted, so he caved in. He wanted to see you as soon as you arrived. You’d better go now. I’ll finish your packing.”

This was noble of Jimmy, for of all the duties of life he loathed packing most.

“Thanks awfully,” said Kennedy, “but don’t you bother. I’ll do it when I get back. But what’s it all about? What made Kay want a man? Why won’t Fenn do? And why me?”

“Well, it’s easy to see why they chose you. They reflected that you’d had the advantage of being in Blackburn’s with me, and seeing how a house really should be run. Kay wants a head for his house. Off he goes to the Old Man. ‘Look here,’ he says, ‘I want somebody shunted into my happy home, or it’ll bust up. And it’s no good trying to put me off with an inferior article, because I won’t have it. It must be somebody who’s been trained from youth up by Silver.’ ‘Then,’ says the Old Man, reflectively, ‘you can’t do better than take Kennedy. I happen to know that Silver has spent years in showing him the straight and narrow path. You take Kennedy.’ ‘All right,’ says Kay; ‘I always thought Kennedy a bit of an ass myself, but if he’s studied under Silver he ought to know how to manage a house. I’ll take him. Advise our Mr. Blackburn to that effect, and ask him to deliver the goods at his earliest convenience. Adoo, mess-mate, adoo!’ And there you are—that’s how it was.”

“But what’s wrong with Fenn?”

“My dear chap! Remember last term. Didn’t Fenn have a regular scrap with Kay, and get shoved into extra for it? And didn’t he wreck the concert in the most sportsmanlike way with that encore of his? Think the Old Man is going to take that grinning? Not much! Fenn made a ripping fifty against Kent in the holidays—I saw him do it—but they don’t count that. It’s a wonder they didn’t ask him to leave. Of course, I think it’s jolly rough on Fenn, but I don’t see that you can blame them. Not the Old Man, at any rate. He couldn’t do anything else. It’s all Kay’s fault that all this has happened, of course. I’m awfully sorry for you having to go into that beastly hole, but from Kay’s point of view it’s a jolly sound move. You may reform the place.”

“I doubt it.”

“So do I—very much. I didn’t say you would—I said you might. I wonder if Kay means to give you a free hand. It all depends on that.”

“Yes. If he’s going to interfere with me as he used to with Fenn, he’ll want to bring in another head to improve on me.”

“Rather a good idea, that,” said Jimmy Silver, laughing, as he always did when any humorous possibilities suggested themselves to him. “If he brings in somebody to improve on you, and then somebody else to improve on him, and then another chap to improve on him, he ought to have a decent house in half-a-dozen years or so.”

“The worst of it is,” said Kennedy, “that I’ve got to go to Kay’s as a sort of rival to Fenn. I shouldn’t mind so much if it wasn’t for that. I wonder how he’ll take it! Do you think he knows about it yet? He didn’t enjoy being head, but that’s no reason why he shouldn’t cut up rough at being shoved back to second prefect. It’s a beastly situation.”

“Beastly,” agreed Jimmy Silver. “Look here,” he added, after a pause, “there’s no reason, you know, why this should make any difference. To us, I mean. What I mean to say is, I don’t see why we shouldn’t see each other just as often, and so on, simply because you are in another house, and all that sort of thing. You know what I mean.”

He spoke shamefacedly, as was his habit whenever he was serious. He liked Kennedy better than anyone he knew, and hated to show his feelings. Anything remotely connected with sentiment made him uncomfortable.

“Of course,” said Kennedy, awkwardly.

“You’ll want a refuge,” said Silver, in his normal manner, “now that you’re going to see wild life in Kay’s. Don’t forget that I’m always at home in my study in the afternoons—admission on presentation of a visiting-card.”

“All right,” said Kennedy, “I’ll remember. I suppose I’d better go and see Blackburn now.”

Mr. Blackburn was in his study. He was obviously disgusted and irritated by what had happened. Loyalty to the headmaster, and an appreciation of his position as a member of the staff led him to try and conceal his feelings as much as possible in his interview with Kennedy, but the latter understood as plainly as if his housemaster had burst into a flow of abuse and complaint. There had always been an excellent understanding—indeed, a friendship—between Kennedy and Mr. Blackburn, and the master was just as sorry to lose his second prefect as the latter was to go.

“Well, Kennedy,” he said, pleasantly. “I hope you had a good time in the holidays. I suppose Silver has told you the melancholy news—that you are to desert us this term? It is a great pity. We shall all be very sorry to lose you. I don’t look forward to seeing you bowl us all out in the house matches next summer,” he added, with a smile, “though we shall expect a few full-pitches to leg, for the sake of old times.”

He meant well, but the picture he conjured up almost made Kennedy break down. Nothing up to the present had made him realise the completeness of his exile so keenly as this remark of Mr. Blackburn’s about his bowling against the side for which he had taken so many wickets in the past. It was a painful thought.

“I am afraid you won’t have quite such a pleasant time in Mr. Kay’s as you have had here,” resumed the housemaster. “Of course, I know that, strictly speaking, I ought not to talk like this about another master’s house; but you can scarcely be unaware of the reasons that have led to this change. You must know that you are being sent to pull Mr. Kay’s house together. This is strictly between ourselves, of course. I think you have a difficult task before you, but I don’t fancy that you will find it too much for you. And mind you come here as often as you please. I am sure Silver and the others will be glad to see you. Goodbye, Kennedy. I think you ought to be getting across now to Mr. Kay’s. I told him that you would be there before half-past nine. Good-night.”

“Good-night, sir,” said Kennedy.

He wandered out into the house dining-room. Somehow, though Kay’s was only next door, he could not get rid of the feeling that he was about to start on a long journey, and would never see his old house again. And in a sense this was so. He would probably visit Blackburn’s to-morrow afternoon, but it would not be the same. Jimmy Silver would greet him like a brother, and he would brew in the same study in which he had always brewed, and sit in the same chair; but it would not be the same. He would be an outsider, a visitor, a stranger within the gates, and—worst of all—a Kayite. Nothing could alter that.

The walls of the dining-room were covered with photographs of the house cricket and football teams for the last fifteen years. Looking at them, he felt more than ever how entirely his school life had been bound up in his house. From his first day at Eckleton he had been taught the simple creed of the Blackburnite, that Eckleton was the finest school in the three kingdoms, and that Blackburn’s was the finest house in the finest school.

Under the gas-bracket by the door hung the first photograph in which he appeared, the cricket team of four years ago. He had just got the last place in front of Challis on the strength of a tremendous catch for the house second in a scratch game two days before the house matches began. It had been a glaring fluke, but it had impressed Denny, the head of the house, who happened to see it, and had won him his place.

He walked round the room, looking at each photograph in turn. It seemed incredible that he had no longer any right to an interest in the success of Blackburn’s. He could have endured leaving all this when his time at school was up, for that would have been the natural result of the passing of years. But to be transplanted abruptly and with a wrench from his native soil was too much. He went upstairs to pack, suffering from as severe an attack of the blues as any youth of eighteen had experienced since blues were first invented.

Jimmy Silver hovered round, while he packed, with expressions of sympathy and bitter remarks concerning Mr. Kay and his wicked works, and, when the operation was concluded, helped Kennedy carry his box over to his new house with the air of one seeing a friend off to the parts beyond the equator.

It was ten o’clock by the time the front door of Kay’s closed upon its new head. Kennedy went to the matron’s sanctum to be instructed in the geography of the house. The matron, a severe lady, whose faith in human nature had been terribly shaken by five years of office in Kay’s, showed him his dormitory and study with a lack of geniality which added a deeper tinge of azure to Kennedy’s blues. “So you’ve come to live here, have you?” her manner seemed to say; “well, I pity you, that’s all. A nice time you’re going to have.”

Kennedy spent the half-hour before going to bed in unpacking his box for the second time, and arranging his books and photographs in the study which had been Weyburn’s. He had nothing to find fault with in the study. It was as large as the one he had owned at Blackburn’s, and, like it, looked out over the school grounds.

At half-past ten the gas gave a flicker and went out, turned off at the main. Kennedy lit a candle and made his way to his dormitory. There now faced him the more than unpleasant task of introducing himself to its inmates. He knew from experience the disconcerting way in which a dormitory greets an intruder. It was difficult to know how to begin matters. It would take a long time, he thought, to explain his presence to their satisfaction.

Fortunately, however, the dormitory was not unprepared. Things get about very quickly in a house. The matron had told the housemaids; the housemaids had handed it on to their ally, the boot boy; the boot boy had told Wren, whom he happened to meet in the passage, and Wren had told everybody else.

There was an uproar going on when Kennedy opened the door, but it died away as he appeared, and the dormitory gazed at the newcomer in absolute and embarrassing silence. Kennedy had not felt so conscious of the public eye being upon him since he had gone out to bat against the M.C.C., on his first appearance in the ranks of the Eckleton eleven. He went to his bed and began to undress without a word, feeling rather than seeing the eyes that were peering at him. When he had completed the performance of disrobing, he blew out the candle and got into bed. The silence was broken by numerous coughs, of that short, suggestive type with which the public schoolboy loves to embarrass his fellow man. From some unidentified corner of the room came a subdued giggle. Then a whispered, “Shut up, you fool!” To which a low voice replied, “All right. I’m not doing anything.”

More coughs, and another outbreak of giggling from a fresh quarter.

“Good-night,” said Kennedy, to the room in general.

There was no reply. The giggler appeared to be rapidly approaching hysterics.

“Shut up that row,” said Kennedy.

The giggling ceased.

The atmosphere was charged with suspicion. Kennedy fell asleep fearing that he was going to have trouble with his dormitory before many nights had passed.

CHAPTER X.

further experiences of an exile.

REAKFAST

on the following morning was a repetition of the dormitory ordeal. Kennedy

walked to his place on Mr. Kay’s right, feeling that everyone was looking at

him, as indeed they were. He understood for the first time the meaning of the

expression, “the cynosure of all eyes.” He was modest by nature, and felt his

position a distinct trial.

REAKFAST

on the following morning was a repetition of the dormitory ordeal. Kennedy

walked to his place on Mr. Kay’s right, feeling that everyone was looking at

him, as indeed they were. He understood for the first time the meaning of the

expression, “the cynosure of all eyes.” He was modest by nature, and felt his

position a distinct trial.

He did not quite know what to say or do with regard to his new house-master at this their first meeting in the latter’s territory. “Come aboard, sir,” occurred to him for a moment as a happy phrase, but he discarded it. To make the situation more awkward, Mr. Kay did not observe him at first, being occupied in assailing a riotous fag at the other end of the table, that youth having succeeded, by a dexterous drive in the ribs, in making a friend of his spill half a cup of coffee. Kennedy did not know whether to sit down without a word or to remain standing until Mr. Kay had time to attend to him. He would have done better to have sat down; Mr. Kay’s greeting, when it came, was not worth waiting for.

“Sit down, Kennedy,” he said, irritably—rebuking people on an empty stomach always ruffled him. “Sit down, sit down.”

Kennedy sat down, and began to toy diffidently with a sausage, remembering, as he did so, certain diatribes of Fenn’s against the food at Kay’s. As he became more intimate with the sausage he admitted to himself that Fenn had had reason. Mr. Kay meanwhile pounded away in moody silence at a plate of kidneys and bacon. It was one of the many grievances which gave the Kayite material for conversation, that Mr. Kay had not the courage of his opinions in the matter of food. He insisted that he fed his house luxuriously, but he refused to brave the mysteries of its bill of fare himself.

Fenn had not come down when Kennedy went in to breakfast. He arrived some ten minutes later, when Kennedy had vanquished the sausage, and was keeping body and soul together with bread and marmalade.

“I cannot have this, Fenn,” snapped Mr. Kay; “you must come down in time.”

Fenn took the rebuke in silence, cast one glance at the sausage which confronted him, and then pushed it away with such unhesitating rapidity that Mr. Kay glared at him as if about to take up the cudgels for the rejected viand. Perhaps he remembered that it scarcely befitted the dignity of a house-master to enter upon a wrangle with a member of his house on the subject of the merits and demerits of sausages, for he refrained, and Fenn was allowed to go on with his meal in peace.

Kennedy’s chief anxiety had been with regard to Fenn. True, the latter could hardly blame him for being made head of Kay’s, since he had not been consulted in the matter, and, if he had been, would have refused the post with horror; but nevertheless the situation might cause a coolness between them. And if Fenn, the only person in the house with whom he was at all intimate, refused to be on friendly terms, his stay in Kay’s would be rendered worse than even he had looked for.

Fenn had not spoken to him at breakfast, but then there was little table talk at Kay’s. Perhaps the quality of the food suggested such gloomy reflections that nobody liked to put them into words.

After the meal Fenn ran upstairs to his study. Kennedy followed him, and opened conversation in his direct way with the subject which he had come to discuss.

“I say,” he said, “I hope you aren’t sick about this. You know I didn’t want to bag your place as head of the house.”

“My dear chap,” said Fenn, “don’t apologise. You’re welcome to it. Being head of Kay’s isn’t such a soft job that one is keen on sticking to it.”

“All the same—” began Kennedy.

“I knew Kay would get at me somehow, of course. I’ve been wondering how all the holidays. I didn’t think of this. Still, I’m jolly glad it’s happened. I now retire into private life, and look on. I’ve taken years off my life sweating to make this house decent, and now I’m going to take a rest and watch you tearing your hair out over the job. I’m awfully sorry for you. I wish they’d roped in some other victim.”

“But you’re still a house prefect, I suppose?”

“I believe so. Kay couldn’t very well make me a fag again.”

“Then you’ll help manage things?”

Fenn laughed.

“Will I, by Jove! I’d like to see myself! I don’t want to do the heavy martyr business and that sort of thing, but I’m hanged if I’m going to take any more trouble over the house. Haven’t you any respect for Mr. Kay’s feelings? He thinks I can’t keep order. Surely you don’t want me to go and shatter his pet beliefs? Anyhow, I’m not going to do it. I’m going to play ‘villagers and retainers’ to your ‘hero.’ If you do anything wonderful with the house, I shall be standing by ready to cheer. But you don’t catch me shoving myself forward. Thank ’eaven I knows me place, as the butler in the play says.”

Kennedy kicked moodily at the leg of the chair which he was holding. The feeling that his whole world had fallen about his ears was increasing with every hour he spent in Kay’s. Last term he and Fenn had been as close friends as you could wish to see. If he had asked Fenn to help him in a tight place then, he knew he could have relied on him. Now his chief desire seemed to be to score off the human race in general, his best friend included. It was a depressing beginning.

“Do you know what the sherry said to the man when he was just going to drink it?” inquired Fenn. “It said, ‘Nemo me impune lacessit.’ That’s how I feel. Kay went out of his way to give me a bad time when I was doing my best to run his house properly, so I don’t see that I’m called upon to go out of my way to work for him.”

“It’s rather rough on me—” Kennedy began. Then a sudden indignation rushed through him. Why should he grovel to Fenn? If Fenn chose to stand out, let him. He was capable of running the house by himself.

“I don’t care,” he said, savagely. “If you can’t see what a cad you’re making of yourself, I’m not going to try to show you. You can do what you jolly well please. I’m not dependent on you. I’ll make this a decent house off my own bat without your help. If you like looking on, you’d better look on. I’ll give you something to look at soon.”

He went out, leaving Fenn with mixed feelings. He would have liked to have followed him, taken back what he had said, and formed an offensive alliance against the black sheep of the house—and also, which was just as important, against the slack sheep, who were good for nothing, either at work or play. But his bitterness against the house-master prevented him. He was not going to take his removal from the leadership of Kay’s as if nothing had happened.

Meanwhile, in the dayrooms and studies, the house had been holding indignation meetings, and at each it had been unanimously resolved that Kay’s had been abominably treated, and that the deposition of Fenn must not be tolerated. Unfortunately, a house cannot do very much when it revolts. It can only show its displeasure in little things, and by an increase of rowdiness. This was the line that Kay’s took. Fenn became a popular hero. Fags, until he kicked them for it, showed a tendency to cheer him whenever they saw him. Nothing could paint Mr. Kay blacker in the eyes of his house, so that Kennedy came in for all the odium. The same fags who had cheered Fenn hooted him on one occasion as he passed the junior day-room. Kennedy stopped short, went in, and presented each inmate of the room with six cuts with a swagger-stick. This summary and Captain Kettle-like move had its effect. There was no more hooting. The fags bethought themselves of other ways of showing their disapproval of their new head.

One genius suggested that they might kill two birds with one stone—snub Kennedy and pay a stately compliment to Fenn by applying to the latter for leave to go out of bounds instead of to the former. As the giving of leave “down town” was the prerogative of the head of the house, and of no other, there was a suggestiveness about this mode of procedure which appealed to the junior dayroom.

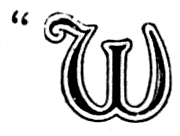

But the star of the junior dayroom was not in the ascendant. Fenn might have quarrelled with Kennedy, and be extremely indignant at his removal from the headship of the house, but he was not the man to forget to play the game. His policy of non-interference did not include underhand attempts to sap Kennedy’s authority. When Gorrick, of the Lower Fourth, the first of the fags to put the ingenious scheme into practice, came to him, still smarting from Kennedy’s castigation, Fenn promptly gave him six more cuts, worse than the first, and kicked him out into the passage. Gorrick naturally did not want to spoil a good thing by giving Fenn’s game away, so he lay low and said nothing, with the result that Wren and three others met with the same fate, only more so, because Fenn’s wrath increased with each visit.

Kennedy, of course, heard nothing of this, or he might perhaps have thought better of Fenn. As for the junior dayroom, it was obliged to work off its emotion by jeering Jimmy Silver from the safety of the touchline when the head of Blackburn’s was refereeing in a match between the juniors of his house and those of Kay’s. Blackburn’s happened to win by four goals and eight tries, a result which the patriotic Kay fag attributed solely to favouritism on the part of the referee.

“I like the kids in your house,” said Jimmy to Kennedy, after the match, when telling the latter of the incident; “there’s no false idea of politeness about them. If they don’t like your decisions, they say so in a shrill treble.”

“Little beasts,” said Kennedy. “I wish I knew who they were. It’s hopeless to try and spot them, of course.”

CHAPTER XI.

the senior dayroom opens fire.

URIOUSLY

enough, it was shortly after this that the junior dayroom ceased almost

entirely to trouble the head of the house. Not that they turned over new

leaves, and modelled their conduct on that of the hero of the Sunday school

story. They were still disorderly, but in a lesser degree; and ragging became a

matter of private enterprise among the fags instead of being, as it had

threatened to be, an organised revolt against the new head. When a Kay’s fag

rioted now, he did so with the air of one endeavouring to amuse himself, not as

if he were carrying on a holy war against the oppressor.

URIOUSLY

enough, it was shortly after this that the junior dayroom ceased almost

entirely to trouble the head of the house. Not that they turned over new

leaves, and modelled their conduct on that of the hero of the Sunday school

story. They were still disorderly, but in a lesser degree; and ragging became a

matter of private enterprise among the fags instead of being, as it had

threatened to be, an organised revolt against the new head. When a Kay’s fag

rioted now, he did so with the air of one endeavouring to amuse himself, not as

if he were carrying on a holy war against the oppressor.

Kennedy’s difficulties were considerably diminished by this change. A head of a house expects the juniors of his house to rag. It is what they are put into the world to do, and there is no difficulty in keeping the thing within decent limits. A revolution is another case altogether. Kennedy was grateful for the change, for it gave him more time to keep an eye on the other members of the house, but he had no idea what had brought it about. As a matter of fact, he had Billy Silver to thank for it. The chief organiser of the movement against Kennedy in the junior dayroom had been the red-haired Wren, who preached war to his fellow fags, partly because he loved to create a disturbance, and partly because Walton, who hated Kennedy, had told him to. Between Wren and Billy Silver a feud had existed since their first meeting. The unsatisfactory conclusion to their encounter in camp had given another lease of life to the feud, and Billy had come back to Kay’s with the fixed intention of smiting his auburn-haired foe hip and thigh at the earliest opportunity. Wren’s attitude with respect to Kennedy gave him a decent excuse. He had no particular regard for Kennedy. The fact that he was a friend of his brother’s was no recommendation. There existed between the two Silvers that feeling which generally exists between an elder and a much younger brother at the same school. Each thought the other a bit of an idiot, and though equal to tolerating him personally, was hanged if he was going to do the same by his friends. In Billy’s circle of acquaintances, Jimmy’s friends were looked upon with cold suspicion as officious meddlers who would give them lines if they found them out of bounds. The aristocrats with whom Jimmy foregathered barely recognised the existence of Billy’s companions. Kennedy’s claim to Billy’s good offices rested on the fact that they both objected to Wren.

So that, when Wren lifted up his voice in the junior dayroom, and exhorted the fags to go and make a row in the passage outside Kennedy’s study, and—from a safe distance, and having previously ensured a means of rapid escape—to fling boots at his door, Billy damped the popular enthusiasm which had been excited by the proposal by kicking Wren with some violence, and begging him not to be an ass. Whereupon they resumed their battle at the point at which it had been interrupted at camp. And when, some five minutes later, Billy, from his seat on his adversary’s chest, offered to go through the same performance with anybody else who wished, the junior dayroom came to the conclusion that his feelings with regard to the new head of the house, however foolish and unpatriotic, had better be respected. And the revolution of the fags had fizzled out from that moment.

In the senior dayroom, however, the flag of battle was still unfurled. It was so obvious that Kennedy had been put into the house as a reformer, and the seniors of Kay’s had such an objection to being reformed, that trouble was only to be expected. It was the custom in most houses for the head of the house, by right of that position, to be also captain of football. The senior dayroom was aggrieved at Kennedy’s taking this post from Fenn. Fenn was in his second year in the school fifteen, and he was the three-quarter who scored most frequently for Eckleton, whereas Kennedy, though practically a certainty for one of the six vacant places in the school scrum, was at present entitled to wear only a second fifteen cap. The claims of Fenn to be captain of Kay’s football were strong. Kennedy had begged him to continue in that position more than once. Fenn’s persistent refusal had helped to increase the coolness between them, and it had also made things more difficult for Kennedy in the house.

It was on the Monday of the third week of term that Kennedy, at Jimmy Silver’s request, arranged a “friendly” between Kay’s and Blackburn’s. There could be no doubt as to which was the better team (for Blackburn’s had been runners up for the Cup the season before), but the better one’s opponents the better the practice. Kennedy wrote out the list and fixed it on the notice board. The match was to be played on the following afternoon.

A football team must generally be made up of the biggest men at the captain’s disposal, so it happened that Walton, Perry, Callingham, and the other leaders of dissension in Kay’s, all figured on the list. The consequence was that the list came in for a good deal of comment in the senior dayroom. There were games every Saturday and Wednesday, and it annoyed Walton and friends that they should have to turn out on an afternoon that was not a half holiday. It was trouble enough playing football on the days when it was compulsory. As for patriotism, no member of the house even pretended to care whether Kay’s put a good team into the field or not. The senior dayroom sat talking over the matter till lights-out. When Kennedy came down next morning, he found his list scribbled over with blue pencil, while across it in bold letters ran the single word

ROT.

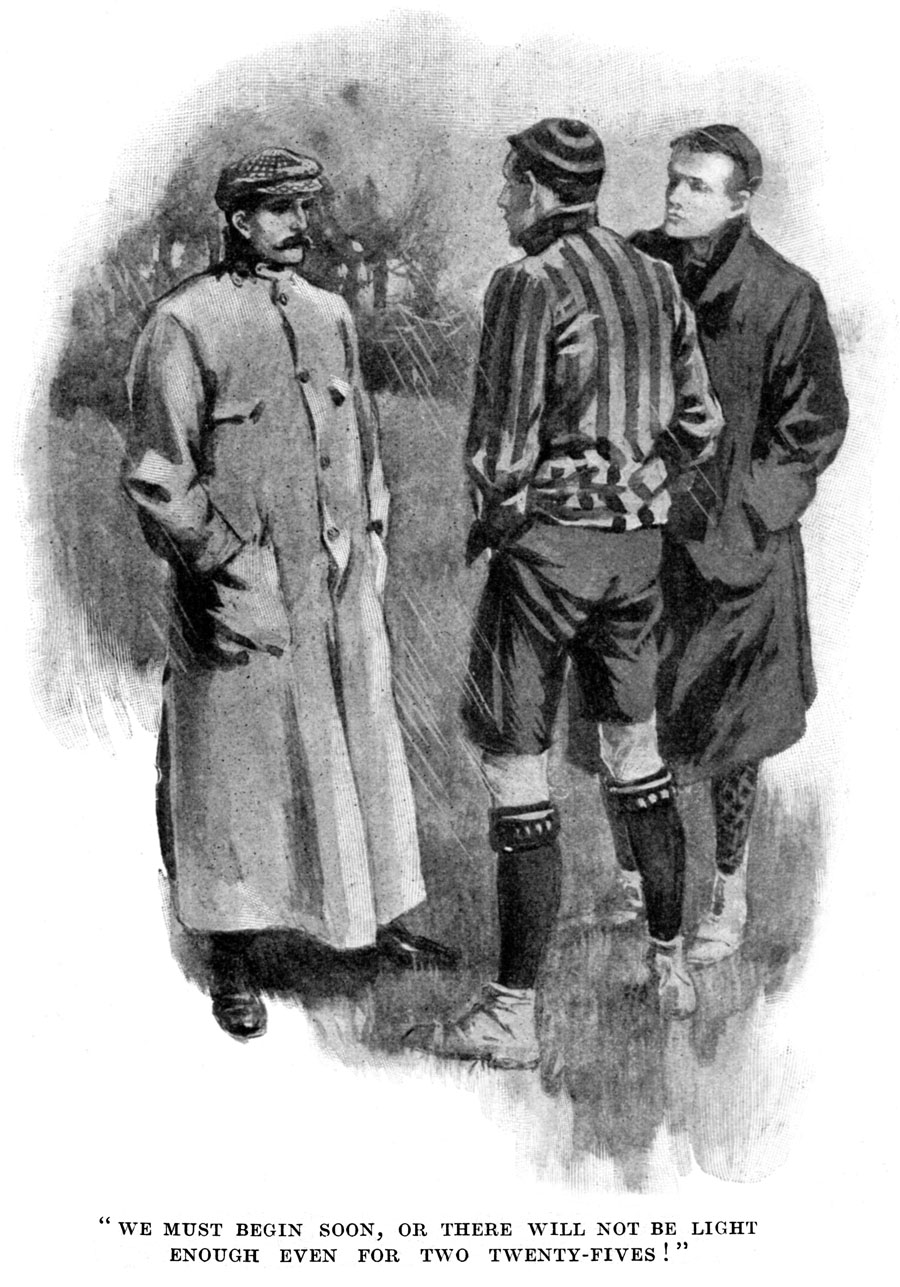

He went to his study, wrote out a fresh copy, and pinned it up in place of the old one. He had been early in coming down that morning, and the majority of the Kayites had not seen the defaced notice. The match was fixed for half-past four. At four a thin rain was falling. The weather had been bad for some days, but on this particular afternoon it readied the limit. In addition to being wet, it was also cold, and Kennedy, as he walked over to the grounds, felt that he would be glad when the game was over. He hoped that Blackburn’s would be punctual, and congratulated himself on his foresight in securing Mr. Blackburn as referee. Some of the staff, when they consented to hold the whistle in a scratch game, invariably kept the teams waiting on the field for half an hour before turning up. Mr. Blackburn, an the other hand, was always punctual. He came out of his house just as Kennedy turned in at the school gates.

“Well, Kennedy,” he said from the depths of his ulster, the collar of which he had turned up over his ears with a prudence which Kennedy, having come out with only a blazer on over his football clothes, distinctly envied, “I hope your men are not going to be late. I don’t think I ever saw a worse day for football. How long were you thinking of playing? Two twenty-fives would be enough for a day like this, I think.”

Kennedy consulted with Jimmy Silver, who came up at this moment, and they agreed without argument that twenty-five minutes each way would be the very thing.

“Where are your men?” asked Jimmy. “I’ve got all our chaps out here, bar Challis, who’ll be out in a few minutes. I left him almost changed.”

Challis appeared a little later, and joined the rest of Blackburn’s team, who were putting in the time and trying to keep warm by running and passing and dropping desultory goals. But, with the exception of Fenn, who stood brooding by himself in the centre of the field, wrapped to the eyes in a huge overcoat, and two other house prefects of Kay’s, who strolled up and down looking as if they wished they were in their studies, there was no sign of the missing team.

“I can’t make it out,” said Kennedy.

“You’re sure you put up the right time?” asked Jimmy Silver.

“Yes, quite.”

It certainly could not be said that Kay’s had had any room for doubt as to the time of the match, for it had appeared in large figures on both notices.

A quarter to five sounded from the college clock.

“We must begin soon,” said Mr. Blackburn, “or there will not be light enough even for two twenty-fives.”

Kennedy felt wretched. Apart from the fact that he was frozen to an icicle and drenched by the rain, he felt responsible for his team, and he could see that Blackburn’s men were growing irritated at the delay, though they did their best to conceal it.

“Can’t we lend them some subs?” suggested Challis, hopefully.

“All right—if you can raise eleven subs,” said Silver. “They’ve only got four men on the field at present.”

Challis subsided.

“Look here,” said Kennedy, “I’m going back to the house to see what’s up. I’ll be back as soon as I can. They must have mistaken the time or something after all.”

He rushed back to the house, and flung open the door of the senior dayroom. It was empty.

Kennedy had expected to find his missing men huddled in a semicircle round the fire, waiting for some one to come and tell them that Blackburn’s had taken the field, and that they could come out now without any fear of having to wait in the rain for the match to begin. This, he thought, would have been the unselfish policy of Kay’s senior dayroom.

But to find nobody was extraordinary.

The thought occurred to him that the team might be changing in their dormitories. He ran upstairs. But all the dormitories were locked, as he might have known they would have been. Coming downstairs again he met his fag, Spencer.

Spencer replied to his inquiry that he had only just come in. He did not know where the team had got to. No, he had not seen any of them.

“Oh, yes, though,” he added, as an afterthought, “I met Walton just now. He looked as if he was going down town.”

Walton had once licked Spencer, and that vindictive youth thought that this might be a chance of getting back at him.

“Oh,” said Kennedy, quietly, “Walton? Did you? Thanks.”

Spencer was disappointed at his lack of excitement. His news did not seem to interest him.

Kennedy went back to the football field to inform Jimmy Silver of the result of his investigations.

CHAPTER XII.

kennedy interviews walton.

’M

very sorry,” he said, when he rejoined the shivering group, “but I’m afraid we

shall have to call this match off. There seems to have been a mistake. None of

my team are anywhere about. I’m awfully sorry, sir,” he added, to Mr. Blackburn,

“to have given you all this trouble for nothing.”

’M

very sorry,” he said, when he rejoined the shivering group, “but I’m afraid we

shall have to call this match off. There seems to have been a mistake. None of

my team are anywhere about. I’m awfully sorry, sir,” he added, to Mr. Blackburn,

“to have given you all this trouble for nothing.”

“Not at all, Kennedy. We must try another day.”

Mr. Blackburn suspected that something untoward had happened in Kay’s to cause this sudden defection of the first fifteen of the house. He knew that Kennedy was having a hard time in his new position, and he did not wish to add to his discomfort by calling for an explanation before an audience. It could not be pleasant for Kennedy to feel that his enemies had scored off him. It was best to preserve a discreet silence with regard to the whole affair, and leave him to settle it for himself.

Jimmy Silver was more curious. He took Kennedy off to tea in his study, sat him down in the best chair in front of the fire, and proceeded to urge him to confess everything.

“Now, then, what’s it all about?” he asked, briskly, spearing a muffin on the fork and beginning to toast.

“It’s no good asking me,” said Kennedy. “I suppose it’s a put-up job to make me look a fool. I ought to have known something of this kind would happen when I saw what they did to my first notice.”

“What was that?”

Kennedy explained.

“This is getting thrilling,” said Jimmy. “Just pass that plate. Thanks. What are you going to do about it?”

“I don’t know. What would you do?”

“My dear chap, I’d first find out who was at the bottom of it—there’s bound to be one man who started the whole thing—and I’d make it my aim in life to give him the warmest ten minutes he’d ever had.”

“That sounds all right. But how would you set about it?”

“Why, touch him up, of course. What else would you do? Before the whole house, too.”

“Supposing he wouldn’t be touched up?”

“Wouldn’t be! He’d have to.”

“You don’t know Kay’s, Jimmy. You’re thinking what you’d do if this had happened in Blackburn’s. The two things aren’t the same. Here the man would probably take it like a lamb. The feeling of the house would be against him. He’d find nobody to back him up. That’s because Blackburn’s is a decent house instead of being a sink like Kay’s. If I tried the touching-up before the whole house game with our chaps, the man would probably reply by going for me, assisted by the whole strength of the company.”

“Well, dash it all then, all you’ve got to do is to call a prefects’ meeting, and he’ll get ten times worse beans from them than he’d have got from you. It’s simple.”

Kennedy stared into the fire pensively.

“I don’t know,” he said. “I bar that prefects’ meeting business. It always seems rather feeble to me, lugging in a lot of chaps to help settle some one you can’t manage yourself. I want to carry this job through on my own.”

“Then you’d better scrap with the man.”

“I think I will.”

Silver stared.

“Don’t be an ass,” he said. “I was only rotting. You can’t go fighting all over the shop as if you were a fag. You’d lose your prefect’s cap if it came out.”

“I could wear my topper,” said Kennedy, with a grin. “You see,” he added, “I’ve not much choice. I must do something. If I took no notice of this business there’d be no holding the house. I should be ragged to death. It’s no good talking about it. Personally, I should prefer touching the chap up to fighting him, and I shall try it on. But he’s not likely to meet me half-way. And if he doesn’t there’ll be an interesting turn-up, and you shall hold the watch. I’ll send a kid round to fetch you when things look like starting. I must go now to interview my missing men. So long. Mind you slip round directly I send for you.”

“Wait a second. Don’t be in such a beastly hurry. Who’s the chap you’re going to fight?”

“I don’t know yet. Walton, I should think. But I don’t know.”

“Walton! By Jove, it’ll be worth seeing, anyhow, if we are both sacked for it when the Old Man finds out.”

Kennedy returned to his study and changed his football boots for a pair of gymnasium shoes. For the job he had in hand it was necessary that he should move quickly, and football boots are a nuisance on a board floor. When he had changed, he called Spencer.

“Go down to the senior dayroom,” he said, “and tell MacPherson I want to see him.”

MacPherson was a long, weak-looking youth. He had been put down to play for the house that day, and had not appeared.

“MacPherson!” said the fag, in a tone of astonishment, “not Walton?”

He had been looking forward to the meeting between Kennedy and his ancient foe, and to have a miserable being like MacPherson offered as a substitute disgusted him.

“If you have no objection,” said Kennedy, politely. “I may want you to fetch Walton later on.”

Spencer vanished, hopeful once more.

“Come in, MacPherson,” said Kennedy, on the arrival of the long one; “shut the door.”

MacPherson did so, feeling as if he were paying a visit to the dentist. As long as there had been others with him in this affair he had looked on it as a splendid idea. But to be singled out like this was quite a different thing.

“Now,” said Kennedy, “Why weren’t you on the field this afternoon?”

“I—er—I was kept in.”

“How long?”

“Oh—er—till about five.”

“What do you call about five?”

“About twenty-five to,” he replied, despondently.

“Now look here,” said Kennedy, briskly, “I’m just going to explain to you exactly how I stand in this business, so you’d better attend. I didn’t ask to be made head of this sewage depôt. If I could have had any choice, I wouldn’t have touched a Kayite with a barge-pole. But since I am head, I’m going to be it, and the sooner you and your senior dayroom crew realise it the better. This sort of thing isn’t going on. I want to know now who it was put up this job. You wouldn’t have the cheek to start a thing like this yourself. Who was it?”

“Well—er——”

“You’d better say, and be quick, too. I can’t wait. Whoever it was, I sha’n’t tell him you told me. And I sha’n’t tell Kay. So now you can go ahead. Who was it?”

“Well—er—Walton.”

“I thought so. Now you can get out. If you see Spencer, send him here.”

Spencer, curiously enough, was just outside the door. So close to it, indeed, that he almost tumbled in when MacPherson opened it.

“Go and fetch Walton,” said Kennedy.

Spencer dashed off delightedly, and in a couple of minutes Walton appeared. He walked in with an air of subdued defiance, and slammed the door.

“Don’t bang the door like that,” said Kennedy. “Why didn’t you turn out to-day?”

“I was kept in.”

“Couldn’t you get out in time to play?”

“No.”

“When did you get out?”

“Six.”

“Not before?”

“I said six.”

“Then how did you manage to go down town—without leave, by the way, but that’s a detail—at half-past five?”

“All right,” said Walton; “better call me a liar.”

“Good suggestion,” said Kennedy, cheerfully; “I will.”

“It’s all very well,” said Walton. “You know jolly well you can say anything you like. I can’t do anything to you. You’d have me up before the prefects.”

“Not a bit of it. This is a private affair between ourselves. I’m not going to drag the prefects into it. You seem to want to make this house worse than it is. I want to make it more or less decent. We can’t both have what we want.”

There was a pause.

“When would it be convenient for you to be touched up before the whole house?” inquired Kennedy, pleasantly.

“What?”

“Well, you see, it seems the only thing. I must take it out of some one for this house-match business, and you started it. Will to-night suit you, after supper?”

“You’ll get it hot if you try to touch me.”

“We’ll see.”

“You’d funk taking me on in a scrap,” said Walton.

“Would I? As a matter of fact, a scrap would suit me just as well. Better. Are you ready now?”

“Quite, thanks,” sneered Walton. “I’ve knocked you out before, and I’ll do it again.”

“Oh, then it was you that night at camp? I thought so. I spotted your style. Hitting a chap when he wasn’t ready, you know, and so on. Now, if you’ll wait a minute, I’ll send across to Blackburn’s for Silver. I told him I should probably want him as a time-keeper to-night.”

“What do you want with Silver. Why won’t Perry do?”

“Thanks, I’m afraid Perry’s time-keeping wouldn’t be impartial enough. Silver, I think, if you don’t mind.”

Spencer was summoned once more, and despatched to Blackburn’s. He returned with Jimmy.

“Come in, Jimmy,” said Kennedy. “Run away, Spencer. Walton and I are just going to settle a point of order which has arisen, Jimmy. Will you hold the watch? We ought just to have time before tea.”

“Where?” asked Silver.

“My dormitory would be the best place. We can move the beds. I’ll go and get the keys.”

Kennedy’s dormitory was the largest in the house. After the beds had been moved back, there was a space in the middle of fifteen feet one way, and twelve the other—not a large ring, but large enough for two fighters who meant business.

Walton took off his coat, waistcoat, and shirt. Kennedy, who was still in football clothes, removed his blazer.

“Half a second,” said Jimmy Silver—”what length rounds?”

“Two minutes?” said Kennedy to Walton.

“All right,” growled Walton.

“Two minutes, then, and half a minute in between.”

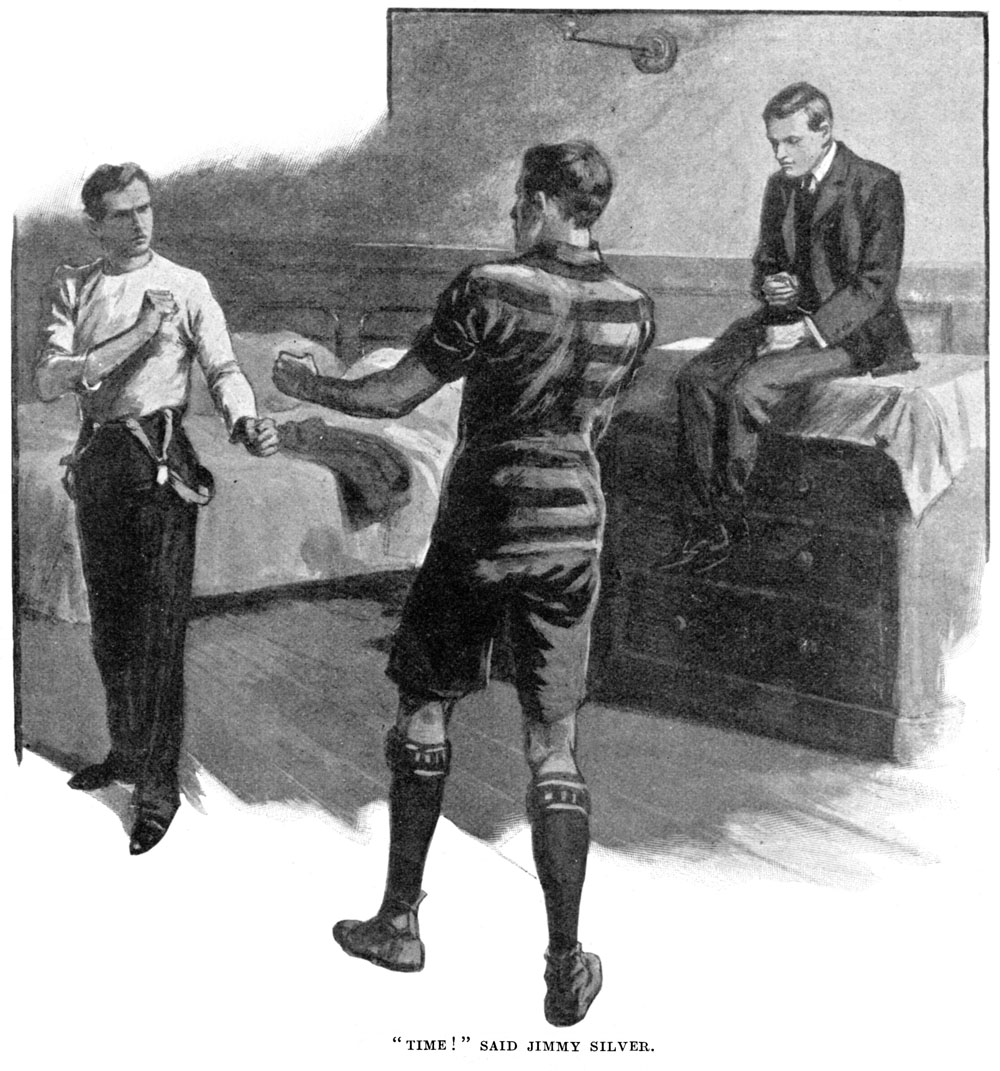

“Are you both ready?” asked Jimmy, from his seat on the chest of drawers.

Kennedy and Walton advanced into the middle of the impromptu ring.

There was dead silence for a moment.

“Time!” said Jimmy Silver.

(To be continued.)

Editor’s notes:

Ch. 10:

cynosure of all eyes: From the Greek for “tail of the dog,” cynosure is an old name for the Little Dipper (Ursa Minor) and especially the North Star at the tip of the tail. Since all stars appear to rotate around it, the word came to refer to anything that is the center of attention.

Nemo me impune lacessit: “No one attacks me with impunity,” the motto of the Royal Stuart house of Scotland at least since 1578 under James VI, later adopted by the Order of the Thistle and by three Scottish regiments of the British army.

Captain Kettle: a sea captain in stories and novels by C. J. Cutcliffe Hyne (1865–1944), a ferocious character unafraid to bend the rules if he thought his cause was just.

Madame Eulalie’s Rare Plums

Madame Eulalie’s Rare Plums