The Captain, February 1909

CHAPTER XXI.

psmith makes inquiries.

SMITH, as was his

habit of a morning when the fierce rush of his commercial duties had abated

somewhat, was leaning gracefully against his desk, musing on many things, when

he was aware that Bristow was standing before him.

SMITH, as was his

habit of a morning when the fierce rush of his commercial duties had abated

somewhat, was leaning gracefully against his desk, musing on many things, when

he was aware that Bristow was standing before him.

Focusing his attention with some reluctance upon this blot on the horizon, he discovered that the exploiter of rainbow waistcoats and satin ties was addressing him.

“I say, Smithy,” said Bristow. He spoke in rather an awed voice.

“Say on, Comrade Bristow,” said Psmith graciously. “You have our ear. You would seem to have something on your chest in addition to that Neapolitan ice garment which, I regret to see, you still flaunt. If it is one tithe as painful as that, you have my sympathy. Jerk it out, Comrade Bristow.”

“Jackson isn’t half copping it from old Bick.”

“Isn’t——? What exactly did you say?”

“He’s getting it hot on the carpet.”

“You wish to indicate,” said Psmith, “that there is some slight disturbance, some passing breeze between Comrades Jackson and Bickersdyke?”

Bristow chuckled.

“Breeze! Blooming hurricane, more like it. I was in Bick’s room just now with a letter to sign, and I tell you, the fur was flying all over the bally shop. There was old Bick cursing for all he was worth, and a little red-faced buffer puffing out his cheeks in an armchair.”

“We all have our hobbies,” said Psmith.

“Jackson wasn’t saying much. He jolly well hadn’t a chance. Old Bick was shooting it out fourteen to the dozen.”

“I have been privileged,” said Psmith, “to hear Comrade Bickersdyke speak both in his sanctum and in public. He has, as you suggest, a ready flow of speech. What, exactly was the cause of the turmoil?”

“I couldn’t wait to hear. I was too jolly glad to get away. Old Bick looked at me as if he could eat me, snatched the letter out of my hand, signed it, and waved his hand at the door as a hint to hop it. Which I jolly well did. He had started jawing Jackson again before I was out of the room.”

“While applauding his hustle,” said Psmith, “I fear that I must take official notice of this. Comrade Jackson is essentially a Sensitive Plant, highly strung, neurotic. I cannot have his nervous system jolted and disorganized in this manner, and his value as a confidential secretary and adviser impaired, even though it be only temporarily. I must look into this. I will go and see if the orgy is concluded. I will hear what Comrade Jackson has to say on the matter. I shall not act rashly, Comrade Bristow. If the man Bickersdyke is proved to have had good grounds for his outbreak, he shall escape uncensured. I may even look in on him and throw him a word of praise. But if I find, as I suspect, that he has wronged Comrade Jackson, I shall be forced to speak sharply to him.”

Mike had left the scene of battle by the time Psmith reached the Cash Department, and was sitting at his desk in a somewhat dazed condition, trying to clear his mind sufficiently to enable him to see exactly how matters stood as concerned himself. He felt confused and rattled. He had known, when he went to the manager’s room to make his statement, that there would be trouble. But, then, trouble is such an elastic word. It embraces a hundred degrees of meaning. Mike had expected sentence of dismissal, and he had got it. So far he had nothing to complain of. But he had not expected it to come to him riding high on the crest of a great, frothing wave of verbal denunciation. Mr. Bickersdyke, through constantly speaking in public, had developed the habit of fluent denunciation to a remarkable extent. He had thundered at Mike as if Mike had been his Majesty’s Government or the Encroaching Alien, or something of that sort. And that kind of thing is a little overwhelming at short range. Mike’s head was still spinning.

It continued to spin; but he never lost sight of the fact round which it revolved, namely, that he had been dismissed from the service of the bank. And for the first time he began to wonder what they would say about this at home.

Up till now the matter had seemed entirely a personal one. He had charged in to rescue the harassed cashier in precisely the same way as that in which he had dashed in to save him from Bill, the Stone-Flinging Scourge of Clapham Common. Mike’s was one of those direct, honest minds which are apt to concentrate themselves on the crisis of the moment, and to leave the consequences out of the question entirely.

What would they say at home? That was the point.

Again, what could he do by way of earning a living? He did not know much about the City and its ways, but he knew enough to understand that summary dismissal from a bank is not the best recommendation one can put forward in applying for another job. And if he did not get another job in the City, what could he do? If it were only summer, he might get taken on somewhere as a cricket professional. Cricket was his line. He could earn his pay at that. But it was very far from being summer.

He had turned the problem over in his mind till his head ached, and had eaten in the process one-third of a wooden pen-holder, when Psmith arrived.

“It has reached me,” said Psmith, “that you and Comrade Bickersdyke have been seen doing the Hackenschmidt-Gotch act on the floor. When my informant left, he tells me, Comrade B. had got a half-Nelson on you, and was biting pieces out of your ear. Is this so?”

Mike got up. Psmith was the man, he felt, to advise him in this crisis. Psmith’s was the mind to grapple with his Hard Case.

“Look here, Smith,” he said, “I want to speak to you. I’m in a bit of a hole, and perhaps you can tell me what to do. Let’s go out and have a cup of coffee, shall we? I can’t tell you about it here.”

“An admirable suggestion,” said Psmith. “Things in the Postage Department are tolerably quiescent at present. Naturally I shall be missed, if I go out. But my absence will not spell irretrievable ruin, as it would at a period of greater commercial activity. Comrades Rossiter and Bristow have studied my methods. They know how I like things to be done. They are fully competent to conduct the business of the department in my absence. Let us, as you say, scud forth. We will go to a Mecca. Why so-called I do not know, nor, indeed, do I ever hope to know. There we may obtain, at a price, a passable cup of coffee, and you shall tell me your painful story.”

The Mecca, except for the curious aroma which pervades all Meccas, was deserted. Psmith, moving a box of dominoes on to the next table, sat down.

“Dominoes,” he said, “is one of the few manly sports which have never had great attractions for me. A cousin of mine, who secured his chess blue at Oxford, would, they tell me, have represented his University in the dominoes match also, had he not unfortunately dislocated the radius bone of his bazooka while training for it. Except for him, there has been little dominoes talent in the Psmith family. Let us merely talk. What of this slight brass-rag-parting to which I alluded just now? Tell me all.”

He listened gravely while Mike related the incidents which had led up to his confession and the results of the same. At the conclusion of the narrative he sipped his coffee in silence for a moment.

“This habit of taking on to your shoulders the harvest of other people’s bloomers,” he said meditatively, “is growing upon you, Comrade Jackson. You must check it. It is like dram-drinking. You begin in a small way by breaking school rules to extract Comrade Jellicoe (perhaps the supremest of all the blitherers I have ever met) from a hole. If you had stopped there, all might have been well. But the thing, once started, fascinated you. Now you have landed yourself with a splash in the very centre of the Oxo in order to do a good turn to Comrade Waller. You must drop it, Comrade Jackson. When you were free and without ties, it did not so much matter. But now that you are confidential secretary and adviser to a Shropshire Psmith, the thing must stop. Your secretarial duties must be paramount. Nothing must be allowed to interfere with them. Yes. The thing must stop before it goes too far.”

“It seems to me,” said Mike, “that it has gone too far. I’ve got the sack. I don’t know how much farther you want it to go.”

Psmith stirred his coffee before replying.

“True,” he said, “things look perhaps a shade rocky just now, but all is not yet lost. You must recollect that Comrade Bickersdyke spoke in the heat of the moment. That generous temperament was stirred to its depths. He did not pick his words. But calm will succeed storm, and we may be able to do something yet. I have some little influence with Comrade Bickersdyke. Wrongly, perhaps,” added Psmith modestly, “he thinks somewhat highly of my judgment. If he sees that I am opposed to this step, he may possibly reconsider it. What Psmith thinks to-day, is his motto, I shall think to-morrow. However, we shall see.”

“I bet we shall!” said Mike ruefully.

“There is, moreover,” continued Psmith, “another aspect to the affair. When you were being put through it, in Comrade Bickersdyke’s inimitably breezy manner, Sir John What’s-his-name was, I am given to understand, present. Naturally, to pacify the aggrieved bart., Comrade B. had to lay it on regardless of expense. In America, as possibly you are aware, there is a regular post of mistake-clerk, whose duty it is to receive in the neck anything that happens to be coming along when customers make complaints. He is hauled into the presence of the foaming customer, cursed, and sacked. The customer goes away appeased. The mistake-clerk, if the harangue has been unusually energetic, applies for a rise of salary. Now, possibly, in your case——”

“In my case,” interrupted Mike, “there was none of that rot. Bickersdyke wasn’t putting it on. He meant every word. Why, dash it all, you know yourself he’d be only too glad to sack me, just to get some of his own back with you.”

Psmith’s eyes opened in pained surprise.

“Get some of his own back!” he repeated. “Are you insinuating, Comrade Jackson, that my relations with Comrade Bickersdyke are not of the most pleasant and agreeable nature possible? How do these ideas get about? I yield to nobody in my respect for our manager. I may have had occasion from time to time to correct him in some trifling matter, but surely he is not the man to let such a thing rankle? No! I prefer to think that Comrade Bickersdyke regards me as his friend and well-wisher, and will lend a courteous ear to any proposal I see fit to make. I hope shortly to be able to prove this to you. I will discuss this little affair of the cheque with him at our ease at the club, and I shall be surprised if we do not come to some arrangement.”

“Look here, Smith,” said Mike earnestly, “for goodness’ sake don’t go playing the goat. There’s no earthly need for you to get lugged into this business. Don’t you worry about me. I shall be all right.”

“I think,” said Psmith, “that you will—when I have chatted with Comrade Bickersdyke.”

CHAPTER XXII.

and takes steps.

N returning to the

bank, Mike found Mr. Waller in the grip of a peculiarly varied set of mixed

feelings. Shortly after Mike’s departure for the Mecca, the cashier had been

summoned once more into the Presence, and had there been informed that, as

apparently he had not been directly responsible for the gross piece of

carelessness by which Sir John had suffered so considerable a loss (here Sir

John puffed out his cheeks like a meditative toad), the matter, as far as he

was concerned, was at an end. On the other hand——! Here Mr. Waller was hauled

over the coals for Incredible Rashness in allowing a mere junior subordinate to

handle important tasks like the paying out of money, and so on, till he felt

raw all over. However, it was not dismissal. That was the great thing. And his

principal sensation was one of relief.

N returning to the

bank, Mike found Mr. Waller in the grip of a peculiarly varied set of mixed

feelings. Shortly after Mike’s departure for the Mecca, the cashier had been

summoned once more into the Presence, and had there been informed that, as

apparently he had not been directly responsible for the gross piece of

carelessness by which Sir John had suffered so considerable a loss (here Sir

John puffed out his cheeks like a meditative toad), the matter, as far as he

was concerned, was at an end. On the other hand——! Here Mr. Waller was hauled

over the coals for Incredible Rashness in allowing a mere junior subordinate to

handle important tasks like the paying out of money, and so on, till he felt

raw all over. However, it was not dismissal. That was the great thing. And his

principal sensation was one of relief.

Mingled with the relief were sympathy for Mike, gratitude to him for having given himself up so promptly, and a curiously dazed sensation, as if somebody had been hitting him on the head with a bolster.

All of which emotions, taken simultaneously, had the effect of rendering him completely dumb when he saw Mike. He felt that he did not know what to say to him. And as Mike, for his part, simply wanted to be let alone, and not compelled to talk, conversation was at something of a standstill in the Cash Department.

After five minutes, it occurred to Mr. Waller that perhaps the best plan would be to interview Psmith. Psmith would know exactly how matters stood. He could not ask Mike point-blank whether he had been dismissed. But there was the probability that Psmith had been informed and would pass on the information.

Psmith received the cashier with a dignified kindliness.

“Oh, er, Smith,” said Mr. Waller, “I wanted just to ask you about Jackson.”

Psmith bowed his head gravely.

“Exactly,” he said. “Comrade Jackson. I think I may say that you have come to the right man. Comrade Jackson has placed himself in my hands, and I am dealing with his case. A somewhat tricky business, but I shall see him through.”

“Has he——?” Mr. Waller hesitated.

“You were saying?” said Psmith.

“Does Mr. Bickersdyke intend to dismiss him?”

“At present,” admitted Psmith, “there is some idea of that description floating—nebulously, as it were—in Comrade Bickersdyke’s mind. Indeed, from what I gather from my client, the push was actually administered, in so many words. But tush! And possibly bah! we know what happens on these occasions, do we not? You and I are students of human nature, and we know that a man of Comrade Bickersdyke’s warm-hearted type is apt to say in the heat of the moment a great deal more than he really means. Men of his impulsive character cannot help expressing themselves in times of stress with a certain generous strength which those who do not understand them are inclined to take a little too seriously. I shall have a chat with Comrade Bickersdyke at the conclusion of the day’s work, and I have no doubt that we shall both laugh heartily over this little episode.”

Mr. Waller pulled at his beard, with an expression on his face that seemed to suggest that he was not quite so confident on this point. He was about to put his doubts into words when Mr. Rossiter appeared, and Psmith, murmuring something about duty, turned again to his ledger. The cashier drifted back to his own department.

It was one of Psmith’s theories of Life, which he was accustomed to propound to Mike in the small hours of the morning with his feet on the mantelpiece, that the secret of success lay in taking advantage of one’s occasional slices of luck, in seizing, as it were, the happy moment. When Mike, who had had the passage to write out ten times at Wrykyn on one occasion as an imposition, reminded him that Shakespeare had once said something about there being a tide in the affairs of men, which, taken at the flood, &c., Psmith had acknowledged with an easy grace that possibly Shakespeare had got on to it first, and that it was but one more proof of how often great minds thought alike.

Though waiving his claim to the copyright of the maxim, he nevertheless had a high opinion of it, and frequently acted upon it in the conduct of his own life.

Thus, when approaching the Senior Conservative Club at five o’clock with the idea of finding Mr. Bickersdyke there, he observed his quarry entering the Turkish Baths which stand some twenty yards from the club’s front door, he acted on his maxim, and decided, instead of waiting for the manager to finish his bath before approaching him on the subject of Mike, to corner him in the Baths themselves.

He gave Mr. Bickersdyke five minutes’ start. Then, reckoning that by that time he would probably have settled down, he pushed open the door and went in himself. And, having paid his money, and left his boots with the boy at the threshold, he was rewarded by the sight of the manager emerging from a box at the far end of the room, clad in the mottled towels which the bather, irrespective of his personal taste in dress, is obliged to wear in a Turkish bath.

Psmith made for the same box. Mr. Bickersdyke’s clothes lay at the head of one of the sofas, but nobody else had staked out a claim. Psmith took possession of the sofa next to the manager’s. Then, humming lightly, he undressed, and made his way downstairs to the Hot Rooms. He rather fancied himself in towels. There was something about them which seemed to suit his figure. They gave him, he thought, rather a debonair look. He paused for a moment before the looking-glass to examine himself, with approval, then pushed open the door of the Hot Rooms and went in.

CHAPTER XXIII.

mr. bickersdyke makes a concession.

R. BICKERSDYKE was

reclining in an easy-chair in the first room, staring before him in the

boiled-fish manner customary in a Turkish Bath. Psmith dropped into the next

seat with a cheery “Good evening.” The manager started as if some firm hand had

driven a bradawl into him. He looked at Psmith with what was intended to be a

dignified stare. But dignity is hard to achieve in a couple of parti-coloured

towels. The stare did not differ to any great extent from the conventional

boiled-fish look, alluded to above.

R. BICKERSDYKE was

reclining in an easy-chair in the first room, staring before him in the

boiled-fish manner customary in a Turkish Bath. Psmith dropped into the next

seat with a cheery “Good evening.” The manager started as if some firm hand had

driven a bradawl into him. He looked at Psmith with what was intended to be a

dignified stare. But dignity is hard to achieve in a couple of parti-coloured

towels. The stare did not differ to any great extent from the conventional

boiled-fish look, alluded to above.

Psmith settled himself comfortably in his chair. “Fancy finding you here,” he said pleasantly. “We seem always to be meeting. To me,” he added, with a reassuring smile, “it is a great pleasure. A very great pleasure indeed. We see too little of each other during office hours. Not that one must grumble at that. Work before everything. You have your duties, I mine. It is merely unfortunate that those duties are not such as to enable us to toil side by side, encouraging each other with word and gesture. However, it is idle to repine. We must make the most of these chance meetings when the work of the day is over.”

Mr. Bickersdyke heaved himself up from his chair and took another at the opposite end of the room. Psmith joined him.

“There’s something pleasantly mysterious, to my mind,” said he chattily, “in a Turkish Bath. It seems to take one out of the hurry and bustle of the everyday world. It is a quiet backwater in the rushing river of Life. I like to sit and think in a Turkish Bath. Except, of course, when I have a congenial companion to talk to. As now. To me——”

Mr. Bickersdyke rose, and went into the next room.

“To me,” continued Psmith, again following, and seating himself beside the manager, “there is, too, something eerie in these places. There is a certain sinister air about the attendants. They glide rather than walk. They say little. Who knows what they may be planning and plotting? That drip-drip again. It may be merely water, but how are we to know that it is not blood? It would be so easy to do away with a man in a Turkish Bath. Nobody has seen him come in. Nobody can trace him if he disappears. These are uncomfortable thoughts, Mr. Bickersdyke.”

Mr. Bickersdyke seemed to think them so. He rose again, and returned to the first room.

“I have made you restless,” said Psmith, in a voice of self-reproach, when he had settled himself once more by the manager’s side. “I am sorry. I will not pursue the subject. Indeed, I believe that my fears are unnecessary. Statistics show, I understand, that large numbers of men emerge in safety every year from Turkish Baths. There was another matter of which I wished to speak to you. It is a somewhat delicate matter, and I am only encouraged to mention it to you by the fact that you are so close a friend of my father’s.”

Mr. Bickersdyke had picked up an early edition of an evening paper, left on the table at his side by a previous bather, and was to all appearances engrossed in it. Psmith, however, not discouraged, proceeded to touch upon the matter of Mike.

“There was,” he said, “some little friction, I hear, in the office to-day in connection with a cheque.” The evening paper hid the manager’s expressive face, but from the fact that the hands holding it tightened their grip Psmith deduced that Mr. Bickersdyke’s attention was not wholly concentrated on the City news. Moreover, his toes wriggled. And when a man’s toes wriggle, he is interested in what you are saying.

“All these petty breezes,” continued Psmith sympathetically, “must be very trying to a man in your position, a man who wishes to be left alone in order to devote his entire thought to the niceties of the higher Finance. It is as if Napoleon, while planning out some intricate scheme of campaign, were to be called upon in the midst of his meditations to bullyrag a private for not cleaning his buttons. Naturally, you were annoyed. Your giant brain, wrenched temporarily from its proper groove, expended its force in one tremendous reprimand of Comrade Jackson. It was as if one had diverted some terrific electric current which should have been controlling a vast system of machinery, and turned it on to annihilate a black-beetle. In the present case, of course, the result is as might have been expected. Comrade Jackson, not realizing the position of affairs, went away with the absurd idea that all was over, that you meant all you said—briefly, that his number was up. I assured him that he was mistaken, but no! He persisted in declaring that all was over, that you had dismissed him from the bank.”

Mr. Bickersdyke lowered the paper and glared bulbously at the old Etonian.

“Mr. Jackson is perfectly right,” he snapped. “Of course I dismissed him.”

“Yes, yes,” said Psmith, “I have no doubt that at the moment you did work the rapid push. What I am endeavouring to point out is that Comrade Jackson is under the impression that the edict is permanent, that he can hope for no reprieve.”

“Nor can he.”

“You don’t mean——?”

“I mean what I say.”

“Ah, I quite understand,” said Psmith, as one who sees that he must make allowances. “The incident is too recent. The storm has not yet had time to expend itself. You have not had leisure to think the matter over coolly. It is hard, of course, to be cool in a Turkish Bath. Your ganglions are still vibrating. Later, perhaps——”

“Once and for all,” growled Mr. Bickersdyke, “the thing is ended. Mr. Jackson will leave the bank at the end of the month. We have no room for fools in the office.”

“You surprise me,” said Psmith. “I should not have thought that the standard of intelligence in the bank was extremely high. With the exception of our two selves, I think that there are hardly any men of real intelligence on the staff. And Comrade Jackson is improving every day. Being, as he is, under my constant supervision, he is rapidly developing a stranglehold on his duties, which——”

“I have no wish to discuss the matter any further.”

“No, no. Quite so, quite so. Not another word. I am dumb.”

“There are limits you see, to the uses of impertinence, Mr. Smith.”

Psmith started.

“You are not suggesting——! You do not mean that I——!”

“I have no more to say. I shall be glad if you will allow me to read my paper.”

Psmith waved a damp hand.

“I should be the last man,” he said stiffly, “to force my conversation on another. I was under the impression that you enjoyed these little chats as keenly as I did. If I was wrong——”

He relapsed into a wounded silence. Mr. Bickersdyke resumed his perusal of the evening paper, and presently, laying it down, rose and made his way to the room where muscular attendants were in waiting to perform that blend of Jiu-Jitsu and Catch-as-catch-can which is the most valuable and at the same time most painful part of a Turkish Bath.

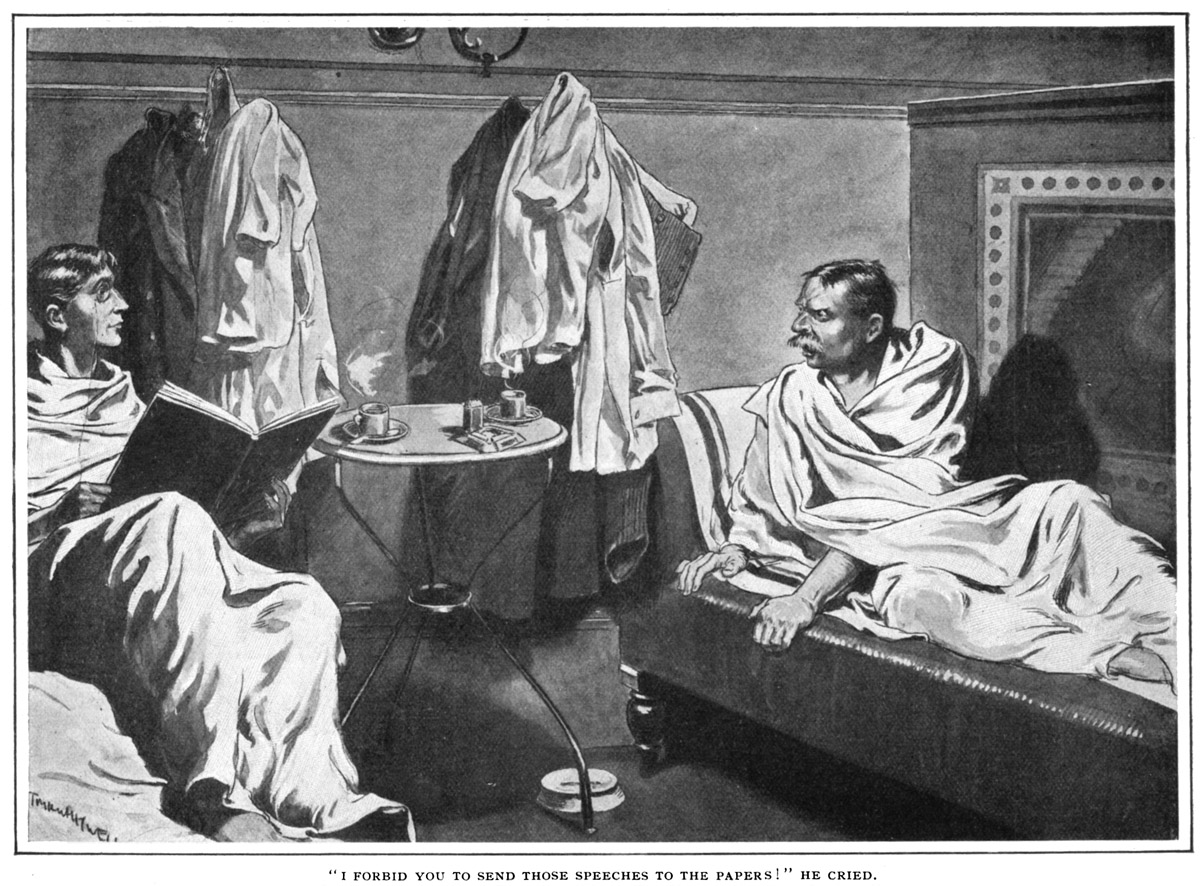

It was not till he was resting on his sofa, swathed from head to foot in a sheet and smoking a cigarette, that he realized that Psmith was sharing his compartment.

He made the unpleasant discovery just as he had finished his first cigarette and lighted his second. He was blowing out the match when Psmith, accompanied by an attendant, appeared in the doorway, and proceeded to occupy the next sofa to himself. All that feeling of dreamy peace, which is the reward one receives for allowing oneself to be melted like wax and kneaded like bread, left him instantly. He felt hot and annoyed. To escape was out of the question. Once one has been scientifically wrapped up by the attendant and placed on one’s sofa, one is a fixture. He lay scowling at the ceiling, resolved to combat all attempt at conversation with a stony silence.

Psmith, however, did not seem to desire conversation. He lay on his sofa motionless for a quarter of an hour, then reached out for a large book which lay on the table, and began to read.

When he did speak, he seemed to be speaking to himself. Every now and then he would murmur a few words, sometimes a single name. In spite of himself, Mr. Bickersdyke found himself listening.

At first the murmurs conveyed nothing to him. Then suddenly a name caught his ear. Strowther was the name, and somehow it suggested something to him. He could not say precisely what. It seemed to touch some chord of memory. He knew no one of the name of Strowther. He was sure of that. And yet it was curiously familiar. An unusual name, too. He could not help feeling that at one time he must have known it quite well.

“Mr. Strowther,” murmured Psmith, “said that the hon. gentleman’s remarks would have been nothing short of treason, if they had not been so obviously the mere babblings of an irresponsible lunatic. Cries of ‘Order, order,’ and a voice, ‘Sit down, fat-head!’ ”

For just one moment Mr. Bickersdyke’s memory poised motionless, like a hawk about to swoop. Then it darted at the mark. Everything came to him in a flash. The hands of the clock whizzed back. He was no longer Mr. John Bickersdyke, manager of the London branch of the New Asiatic Bank, lying on a sofa in the Cumberland Street Turkish Baths. He was Jack Bickersdyke, clerk in the employ of Messrs. Norton and Biggleswade, standing on a chair and shouting “Order! order!” in the Masonic Room of the “Red Lion” at Tulse Hill, while the members of the Tulse Hill Parliament, divided into two camps, yelled at one another, and young Tom Barlow, in his official capacity as Mister Speaker, waved his arms dumbly, and banged the table with his mallet in his efforts to restore calm.

He remembered the whole affair as if it had happened yesterday. It had been a speech of his own which had called forth the above expression of opinion from Strowther. He remembered Strowther now, a pale, spectacled clerk in Blumenfeld and Abrahams, an inveterate upholder of the throne, the House of Lords and all constituted authority. Strowther had objected to the socialistic sentiments of his speech in connection with the Budget, and there had been a disturbance unparalleled even in the Tulse Hill Parliament, where disturbances were frequent and loud. . . .

Psmith looked across at him with a bright smile. “They report you verbatim,” he said. “And rightly. A more able speech I have seldom read. I like the bit where you call the Royal Family blood-suckers. Even then, it seems you knew how to express yourself fluently and well.”

Mr. Bickersdyke sat up. The hands of the clock had moved again, and he was back in what Psmith had called the live, vivid present.

“What have you got there?” he demanded.

“It is a record,” said Psmith, “of the meeting of an institution called the Tulse Hill Parliament. A bright, chatty little institution, too, if one may judge by these reports. You in particular, if I may say so, appear to have let yourself go with refreshing vim. Your political views have changed a great deal since those days, have they not? It is extremely interesting. A most fascinating study for political students. When I send these speeches of yours to the Clarion——”

Mr. Bickersdyke bounded on his sofa.

“What!” he cried.

“I was saying,” said Psmith, “that the Clarion will probably make a most interesting comparison between these speeches and those you have been making at Kenningford.”

“I—I—I forbid you to make any mention of these speeches.”

Psmith hesitated.

“It would be great fun seeing what the papers said,” he protested.

“Great fun!”

“It is true,” mused Psmith, “that in a measure, it would dish you at the election. From what I saw of those light-hearted lads at Kenningford the other night, I should say they would be so amused that they would only just have enough strength left to stagger to the poll and vote for your opponent.”

Mr. Bickersdyke broke out into a cold perspiration.

“I forbid you to send those speeches to the papers,” he cried.

Psmith reflected.

“You see,” he said at last, “it is like this. The departure of Comrade Jackson, my confidential secretary and adviser, is certain to plunge me into a state of the deepest gloom. The only way I can see at present by which I can ensure even a momentary lightening of the inky cloud is the sending of these speeches to some bright paper like the Clarion. I feel certain that their comments would wring, at any rate, a sad, sweet smile from me. Possibly even a hearty laugh. I must, therefore, look on these very able speeches of yours in something of the light of an antidote. They will stand between me and black depression. Without them I am in the cart. With them I may possibly buoy myself up.”

Mr. Bickersdyke shifted uneasily on his sofa. He glared at the floor. Then he eyed the ceiling as if it were a personal enemy of his. Finally he looked at Psmith. Psmith’s eyes were closed in peaceful meditation.

“Very well,” said he at last. “Jackson shall stop.”

Psmith came out of his thoughts with a start.

“You were observing——?” he said.

“I shall not dismiss Jackson,” said Mr. Bickersdyke.

Psmith smiled winningly.

“Just as I had hoped,” he said. “Your very justifiable anger melts before reflection. The storm subsides, and you are at leisure to examine the matter dispassionately. Doubts begin to creep in. Possibly, you say to yourself, I have been too hasty, too harsh. Justice must be tempered with mercy. I have caught Comrade Jackson bending, you add (still to yourself), but shall I press home my advantage too ruthlessly? No, you cry, I will abstain. And I applaud your action. I like to see this spirit of gentle toleration. It is bracing and comforting. As for these excellent speeches,” he added, “I shall, of course, no longer have any need of their consolation. I can lay them aside. The sunlight can now enter and illumine my life through more ordinary channels. The cry goes round, Psmith is himself again.”

Mr. Bickersdyke said nothing. Unless a snort of fury may be counted as anything.

CHAPTER XXIV.

the spirit of unrest.

URING the following

fortnight, two things happened which materially altered Mike’s position in the

bank.

URING the following

fortnight, two things happened which materially altered Mike’s position in the

bank.

The first was that Mr. Bickersdyke was elected a member of Parliament. He got in by a small majority amidst scenes of disorder of a nature unusual even in Kenningford. Psmith, who went down on the polling-day to inspect the revels and came back with his hat smashed in, reported that, as far as he could see, the electors of Kenningford seemed to be in just that state of happy intoxication which might make them vote for Mr. Bickersdyke by mistake. Also it had been discovered, on the eve of the poll, that the bank manager’s opponent, in his youth, had been educated at a school in Germany, and had subsequently spent two years at Heidelberg University. These damaging revelations were having a marked effect on the warm-hearted patriots of Kenningford, who were now referring to the candidate in thick but earnest tones as “the German Spy.”

“So that taking everything into consideration,” said Psmith, summing up, “I fancy that Comrade Bickersdyke is home.”

And the papers next day proved that he was right.

“A hundred and fifty-seven,” said Psmith, as he read his paper at breakfast. “Not what one would call a slashing victory. It is fortunate for Comrade Bickersdyke, I think, that I did not send those very able speeches of his to the Clarion.”

Till now Mike had been completely at a loss to understand why the manager had sent for him on the morning following the scene about the cheque, and informed him that he had reconsidered his decision to dismiss him. Mike could not help feeling that there was more in the matter than met the eye. Mr. Bickersdyke had not spoken as if it gave him any pleasure to reprieve him. On the contrary, his manner was distinctly brusque. Mike was thoroughly puzzled. To Psmith’s statement, that he had talked the matter over quietly with the manager and brought things to a satisfactory conclusion, he had paid little attention. But now he began to see light.

“Great Scott, Smith,” he said, “did you tell him you’d send those speeches to the papers if he sacked me?”

Psmith looked at him through his eye-glass, and helped himself to another piece of toast.

“I am unable,” he said, “to recall at this moment the exact terms of the very pleasant conversation I had with Comrade Bickersdyke on the occasion of our chance meeting in the Turkish Bath that afternoon; but, thinking things over quietly now that I have more leisure, I cannot help feeling that he may possibly have read some such intention into my words. You know how it is in these little chats, Comrade Jackson. One leaps to conclusions. Some casual word I happened to drop may have given him the idea you mention. At this distance of time it is impossible to say with any certainty. Suffice it that all has ended well. He did reconsider his resolve. I shall be only too happy if it turns out that the seed of the alteration in his views was sown by some careless word of mine. Perhaps we shall never know.”

Mike was beginning to mumble some awkward words of thanks, when Psmith resumed his discourse.

“Be that as it may, however,” he said, “we cannot but perceive that Comrade Bickersdyke’s election has altered our position to some extent. As you have pointed out, he may have been influenced in this recent affair by some chance remark of mine about those speeches. Now, however, they will cease to be of any value. Now that he is elected he has nothing to lose by their publication. I mention this by way of indicating that it is possible that, if another painful episode occurs, he may be more ruthless.”

“I see what you mean,” said Mike. “If he catches me on the hop——”

“Or bend.”

“——again, he’ll simply go ahead and sack me.”

“That,” said Psmith, “is more or less the position of affairs.”

The other event which altered Mike’s life in the bank was his removal from Mr. Waller’s department to the Fixed Deposits. The work in the Fixed Deposits was less pleasant, and Mr. Gregory, the head of the department, was not of Mr. Waller’s type. Mr. Gregory, before joining the home-staff of the New Asiatic Bank, had spent a number of years with a firm in the Far East, where he had acquired a liver and a habit of addressing those under him in a way that suggested the mate of a tramp steamer. Even on the days when his liver was not troubling him, he was truculent. And when, as usually happened, it did trouble him, he was a perfect fountain of abuse. Mike and he hated each other from the first. The work in the Fixed Deposits was not really difficult, when you got the hang of it, but there was a certain amount of confusion in it to a beginner; and Mike, in commercial matters, was as raw a beginner as ever began. In the two other departments through which he had passed, he had done tolerably well. As regarded his work in the Postage Department, stamping letters and taking them down to the post office was just about his form. It was the sort of work on which he could really get a grip. And in the Cash Department, Mr. Waller’s mild patience had helped him through. But with Mr. Gregory it was different. Mike hated being shouted at. It confused him. And Mr. Gregory invariably shouted. He always spoke as if he were competing against a high wind. With Mike he shouted more than usual. On his side, it must be admitted that Mike was something out of the common run of bank clerks. The whole system of banking was a horrid mystery to him. He did not understand why things were done, or how the various departments depended on and dove-tailed into one another. Each department seemed to him something separate and distinct. Why they were all in the same building at all he never really gathered. He knew that it could not be purely from motives of sociability, in order that the clerks might have each other’s company during slack spells. That much he suspected, but beyond that he was vague.

It naturally followed that, after having grown, little by little, under Mr. Waller’s easy-going rule, to enjoy life in the bank, he now suffered a reaction. Within a day of his arrival in the Fixed Deposits he was loathing the place as earnestly as he had loathed it on the first morning.

Psmith, who had taken his place in the Cash Department, reported that Mr. Waller was inconsolable at his loss.

“I do my best to cheer him up,” he said, “and he smiles bravely every now and then. But when he thinks I am not looking, his head droops and that wistful expression comes into his face. The sunshine has gone out of his life.”

It had just come into Mike’s, and, more than anything else, was making him restless and discontented. That is to say, it was now late spring: the sun shone cheerfully on the City; and cricket was in the air. And that was the trouble.

In the dark days, when everything was fog and slush, Mike had been contented enough to spend his mornings and afternoons in the bank, and go about with Psmith at night. Under such conditions, London is the best place in which to be, and the warmth and light of the bank were pleasant.

But now things had changed. The place had become a prison. With all the energy of one who had been born and bred in the country, Mike hated having to stay indoors on days when all the air was full of approaching summer. There were mornings when it was almost more than he could do to push open the swing-doors, and go out of the fresh air into the stuffy atmosphere of the bank.

The days passed slowly, and the cricket season began. Instead of being a relief, this made matters worse. The little cricket he could get only made him want more. It was as if a starving man had been given a handful of wafer biscuits.

If the summer had been wet, he might have been less restless. But, as it happened, it was unusually fine. After a week of cold weather at the beginning of May, a hot spell set in. May passed in a blaze of sunshine. Large scores were made all over the country.

Mike’s name had been down for the M.C.C. for some years, and he had become a member during his last season at Wrykyn. Once or twice a week he managed to get up to Lord’s for half an hour’s practice at the nets; and on Saturdays the bank had matches, in which he generally managed to knock the cover off rather ordinary club bowling. But it was not enough for him.

June came, and with it more sunshine. The atmosphere of the bank seemed more oppressive than ever.

CHAPTER XXV.

a telephone.

F one looks closely

into those actions which are apparently due to sudden impulse, one generally

finds that the sudden impulse was merely the last of a long series of events

which led up to the action. Alone, it would not have been powerful enough to

effect anything. But, coming after the way has been paved for it, it is irresistible.

The hooligan who bonnets a policeman is apparently the victim of a sudden

impulse. In reality, however, the bonneting is due to weeks of daily encounters

with the constable, at each of which meetings the dislike for his helmet and

the idea of smashing it in grow a little larger, till finally they blossom into

the deed itself.

F one looks closely

into those actions which are apparently due to sudden impulse, one generally

finds that the sudden impulse was merely the last of a long series of events

which led up to the action. Alone, it would not have been powerful enough to

effect anything. But, coming after the way has been paved for it, it is irresistible.

The hooligan who bonnets a policeman is apparently the victim of a sudden

impulse. In reality, however, the bonneting is due to weeks of daily encounters

with the constable, at each of which meetings the dislike for his helmet and

the idea of smashing it in grow a little larger, till finally they blossom into

the deed itself.

This was what happened in Mike’s case. Day by day, through the summer, as the City grew hotter and stuffier, his hatred of the bank became more and more the thought that occupied his mind. It only needed a moderately strong temptation to make him break out and take the consequences.

Psmith noticed his restlessness and endeavoured to soothe it.

“All is not well,” he said, “with Comrade Jackson, the Sunshine of the Home. I note a certain wanness of the cheek. The peach-bloom of your complexion is no longer up to sample. Your eye is wild; your merry laugh no longer rings through the bank, causing nervous customers to leap into the air with startled exclamations. You have the manner of one whose only friend on earth is a yellow dog, and who has lost the dog. Why is this, Comrade Jackson?”

They were talking in the flat at Clement’s Inn. The night was hot. Through the open windows the roar of the Strand sounded faintly. Mike walked to the window and looked out.

“I’m sick of all this rot,” he said shortly.

Psmith shot an inquiring glance at him, but said nothing. This restlessness of Mike’s was causing him a good deal of inconvenience, which he bore in patient silence, hoping for better times. With Mike obviously discontented and out of tune with all the world, there was but little amusement to be extracted from the evenings now. Mike did his best to be cheerful, but he could not shake off the caged feeling which made him restless.

“What rot it all is!” went on Mike, sitting down again. “What’s the good of it all? You go and sweat all day at a desk, day after day, for about twopence a year. And when you’re about eighty-five, you retire. It isn’t living at all. It’s simply being a bally vegetable.”

“You aren’t hankering, by any chance, to be a pirate of the Spanish main, or anything like that, are you?” inquired Psmith.

“And all this rot about going out East,” continued Mike. “What’s the good of going out East?”

“I gather from casual chit-chat in the office that one becomes something of a blood when one goes out East,” said Psmith. “Have a dozen native clerks under you, all looking up to you as the Last Word in magnificence, and end by marrying the Governor’s daughter.”

“End by getting some foul sort of fever, more likely, and being booted out as no further use to the bank.”

“You look on the gloomy side, Comrade Jackson. I seem to see you sitting in an armchair, fanned by devoted coolies, telling some Eastern potentate that you can give him five minutes.”

“Rot,” said Mike.

“Not at all. I understand that being in a bank in the Far East is one of the world’s softest jobs. Millions of natives hang on your lightest word. Enthusiastic rajahs draw you aside and press jewels into your hand as a token of respect and esteem. When on an elephant’s back you pass, somebody beats on a booming brass gong! The Banker of Bhong! Isn’t your generous young heart stirred to any extent by the prospect? I am given to understand——”

“I’ve a jolly good mind to chuck up the whole thing and become a pro. I’ve got a birth qualification for Surrey. It’s about the only thing I could do any good at.”

Psmith’s manner became fatherly.

“You’re all right,” he said. “The hot weather has given you that tired feeling. What you want is a change of air. We will pop down together hand in hand this week-end to some seaside resort. You shall build sand castles, while I lie on the beach and read the paper. In the evening we will listen to the band, or stroll on the esplanade, not so much because we want to, as to give the natives a treat. Possibly, if the weather continues warm, we may even paddle. A vastly exhilarating pastime, I am led to believe, and so strengthening for the ankles. And on Monday morning we will return, bronzed and bursting with health, to our toil once more.”

“I’m going to bed,” said Mike, rising.

Psmith watched him lounge from the room, and shook his head sadly. All was not well with his confidential secretary and adviser.

The next day, which was a Thursday, found Mike no more reconciled to the prospect of spending from ten till five in the company of Mr. Gregory and the ledgers. He was silent at breakfast, and Psmith, seeing that things were still wrong, abstained from conversation. Mike propped the Sportsman up against the hot-water jug, and read the cricket news. His county, captained by brother Joe, had, as he had learned already from yesterday’s evening paper, beaten Sussex by five wickets at Brighton. To-day they were due to play Middlesex at Lord’s. Mike thought that he would try to get off early, and go and see some of the first day’s play.

As events turned out, he got off a good deal earlier, and saw a good deal more of the first day’s play than he had anticipated.

He had just finished the preliminary stages of the morning’s work, which consisted mostly of washing his hands, changing his coat, and eating a section of a pen-holder, when William, the messenger, approached.

“You’re wanted on the ’phone, Mr. Jackson.”

The New Asiatic Bank, unlike the majority of London banks, was on the telephone, a fact which Psmith found a great convenience when securing seats at the theatre. Mike went to the box and took up the receiver.

“Hullo!” he said.

“Who’s that?” said an agitated voice. “Is that you, Mike? I’m Joe.”

“Hullo, Joe,” said Mike. “What’s up? I’m coming to see you this evening. I’m going to try and get off early.”

“Look here, Mike, are you busy at the bank just now?”

“Not at the moment. There’s never anything much going on before eleven.”

“I mean, are you busy to-day? Could you possibly manage to get off and play for us against Middlesex?”

Mike nearly dropped the receiver.

“What!” he cried.

“There’s been the dickens of a mix-up. We’re one short, and you’re our only hope. We can’t possibly get another man in the time. We start in half an hour. Can you play?”

For the space of, perhaps, one minute, Mike thought.

“Well?” said Joe’s voice.

The sudden vision of Lord’s ground, all green and cool in the morning sunlight, was too much for Mike’s resolution, sapped as it was by days of restlessness. The feeling surged over him that whatever happened afterwards, the joy of the match in perfect weather on a perfect wicket would make it worth while. What did it matter what happened afterwards?

“All right, Joe,” he said. “I’ll hop into a cab now, and go and get my things.”

“Good man,” said Joe, hugely relieved.

(To be concluded.)

Madame Eulalie’s Rare Plums

Madame Eulalie’s Rare Plums