The Captain, November 1909

* Former tales about “Psmith” are “The Lost Lambs” and “The New Fold,” in Vols. XIX and XX of The Captain.

CHAPTER VIII.

the honeyed word.

ASTER Maloney’s statement that “about ’steen

visitors” had arrived in addition to Messrs. Asher, Waterman, and the Rev.

Philpotts proved to have been due to a great extent to a somewhat feverish

imagination. There were only five men in the room.

ASTER Maloney’s statement that “about ’steen

visitors” had arrived in addition to Messrs. Asher, Waterman, and the Rev.

Philpotts proved to have been due to a great extent to a somewhat feverish

imagination. There were only five men in the room.

As Psmith entered, every eye was turned upon him. To an outside spectator he would have seemed rather like a very well-dressed Daniel introduced into a den of singularly irritable lions. Five pairs of eyes were smouldering with a long-nursed resentment. Five brows were corrugated with wrathful lines. Such, however, was the simple majesty of Psmith’s demeanour that for a moment there was dead silence. Not a word was spoken as he paced, wrapped in thought, to the editorial chair. Stillness brooded over the room as he carefully dusted that piece of furniture, and, having done so to his satisfaction, hitched up the knees of his trousers and sank gracefully into a sitting position.

This accomplished, he looked up and started. He gazed round the room.

“Ha! I am observed!” he murmured.

The words broke the spell. Instantly, the five visitors burst simultaneously into speech.

“Are you the acting editor of this paper?”

“I wish to have a word with you, sir.”

“Mr. Windsor, I presume?”

“Pardon me!”

“I should like a few moments’ conversation.”

The start was good and even; but the gentleman who said “Pardon me!” necessarily finished first with the rest nowhere.

Psmith turned to him, bowed, and fixed him with a benevolent gaze through his eye-glass.

“Are you Mr. Windsor, sir, may I ask?” inquired the favoured one.

The others paused for the reply.

“Alas! no,” said Psmith with manly regret.

“Then who are you?”

“I am Psmith.”

There was a pause.

“Where is Mr. Windsor?”

“He is, I fancy, champing about forty cents’ worth of lunch at some neighbouring hostelry.”

“When will he return?”

“Anon. But how much anon I fear I cannot say.”

The visitors looked at each other.

“This is exceedingly annoying,” said the man who had said “Pardon me!” “I came for the express purpose of seeing Mr. Windsor.”

“So did I,” chimed in the rest. “Same here. So did I.”

Psmith bowed courteously.

“Comrade Windsor’s loss is my gain. Is there anything I can do for you?”

“Are you on the editorial staff of this paper?”

“I am acting sub-editor. The work is not light,” added Psmith gratuitously. “Sometimes the cry goes round, ‘Can Psmith get through it all? Will his strength support his unquenchable spirit?’ But I stagger on. I do not repine. I——”

“Then maybe you can tell me what all this means?” said a small round gentleman who so far had done only chorus work.

“If it is in my power to do so, it shall be done, Comrade——I have not the pleasure of your name?”

“My name is Waterman, sir. I am here on behalf of my wife, whose name you doubtless know.”

“Correct me if I am wrong,” said Psmith, “but I should say it, also, was Waterman.”

“Luella Granville Waterman, sir,” said the little man proudly. Psmith removed his eye-glass, polished it, and replaced it in his eye. He felt that he must run no risk of not seeing clearly the husband of one who, in his opinion, stood alone in literary circles as a purveyor of sheer bilge.

“My wife,” continued the little man, producing an envelope and handing it to Psmith, “has received this extraordinary communication from a man signing himself W. Windsor. We are both at a loss to make head or tail of it.”

Psmith was reading the letter.

“It seems reasonably clear to me,” he said.

“It is an outrage. My wife has been a contributor to this journal from its foundation. Her work has given every satisfaction to Mr. Wilberfloss. And now, without the slightest warning, comes this peremptory dismissal from W. Windsor. Who is W. Windsor? Where is Mr. Wilberfloss?”

The chorus burst forth. It seemed that that was what they all wanted to know: Who was W. Windsor? Where was Mr. Wilberfloss?

“I am the Reverend Edwin T. Philpotts, sir,” said a cadaverous-looking man with pale blue eyes and a melancholy face. “I have contributed ‘Moments of Meditation’ to this journal for a very considerable period of time.”

“I have read your page with the keenest interest,” said Psmith. “I may be wrong, but yours seems to me work which the world will not willingly let die.”

The Reverend Edwin’s frosty face thawed into a bleak smile.

“And yet,” continued Psmith, “I gather that Comrade Windsor, on the other hand, actually wishes to hurry on its decease. It is these strange contradictions, these clashings of personal taste, which make up what we call life. Here we have, on the one hand—”

A man with a face like a walnut, who had hitherto lurked almost unseen behind a stout person in a serge suit, bobbed into the open, and spoke his piece.

“Where’s this fellow Windsor? W. Windsor. That’s the man we want to see. I’ve been working for this paper without a break, except when I had the mumps, for four years, and I’ve reason to know that my page was as widely read and appreciated as any in New York. And now up comes this Windsor fellow, if you please, and tells me in so many words the paper’s got no use for me.”

“These are life’s tragedies,” murmured Psmith.

“What’s he mean by it? That’s what I want to know. And that’s what these gentlemen want to know— See here,——”

“I am addressing—?” said Psmith.

“Asher’s my name. B. Henderson Asher. I write ‘Moments of Mirth.’ ”

A look almost of excitement came into Psmith’s face, such a look as a visitor to a foreign land might wear when confronted with some great national monument. That he should be privileged to look upon the author of “Moments of Mirth” in the flesh, face to face, was almost too much.

“Comrade Asher,” he said reverently, “may I shake your hand?”

The other extended his hand with some suspicion.

“Your ‘Moments of Mirth,’ ” said Psmith, shaking it, “have frequently reconciled me to the toothache.”

He reseated himself.

“Gentlemen,” he said, “this is a painful case. The circumstances, as you will readily admit when you have heard all, are peculiar. You have asked me where Mr. Wilberfloss is. I do not know.”

“You don’t know!” exclaimed Mr. Waterman.

“I don’t know. You don’t know. They,” said Psmith, indicating the rest with a wave of the hand, “don’t know. Nobody knows. His locality is as hard to ascertain as that of a black cat in a coal-cellar on a moonless night. Shortly before I joined this journal, Mr. Wilberfloss, by his doctor’s orders, started out on a holiday, leaving no address. No letters were to be forwarded. He was to enjoy complete rest. Where is he now? Who shall say? Possibly legging it down some rugged slope in the Rockies, with two bears and a wild cat in earnest pursuit. Possibly in the midst of some Florida everglade, making a noise like a piece of meat in order to snare crocodiles. Possibly in Canada, baiting moose-traps. We have no data.”

Silent consternation prevailed among the audience. Finally the Rev. Edwin T. Philpotts was struck with an idea.

“Where is Mr. White?” he asked.

The point was well received.

“Yes, where’s Mr. Benjamin White?” chorussed the rest.

Psmith shook his head.

“In Europe. I cannot say more.”

The audience’s consternation deepened.

“Then, do you mean to say,” demanded Mr. Asher, “that this fellow Windsor’s the boss here, that what he says goes?”

Psmith bowed.

“With your customary clear-headedness, Comrade Asher, you have got home on the bull’s-eye first pop. Comrade Windsor is indeed the boss. A man of intensely masterful character, he will brook no opposition. I am powerless to sway him. Suggestions from myself as to the conduct of the paper would infuriate him. He believes that radical changes are necessary in the programme of Cosy Moments, and he means to put them through if it snows. Doubtless he would gladly consider your work if it fitted in with his ideas. A snappy account of a glove-fight, a spine-shaking word-picture of a railway smash, or something on those lines, would be welcomed. But——”

“I have never heard of such a thing,” said Mr. Waterman indignantly.

Psmith sighed.

“Some time ago,” he said, “—how long it seems!—I remember saying to a young friend of mine of the name of Spiller, ‘Comrade Spiller, never confuse the unusual with the impossible.’ It is my guiding rule in life. It is unusual for the substitute-editor of a weekly paper to do a Captain Kidd act and take entire command of the journal on his own account; but is it impossible? Alas no. Comrade Windsor has done it. That is where you, Comrade Asher, and you, gentlemen, have landed yourselves squarely in the broth. You have confused the unusual with the impossible.”

“But what is to be done?” cried Mr. Asher.

“I fear that there is nothing to be done, except wait. The present régime is but an experiment. It may be that when Comrade Wilberfloss, having dodged the bears and eluded the wild-cat, returns to his post at the helm of this journal, he may decide not to continue on the lines at present mapped out. He should be back in about ten weeks.”

“Ten weeks!”

“I fancy that was to be the duration of his holiday. Till then my advice to you gentlemen is to wait. You may rely on me to keep a watchful eye upon your interests. When your thoughts tend to take a gloomy turn, say to yourselves, ‘All is well. Psmith is keeping a watchful eye upon our interests.’ ”

“All the same, I should like to see this W. Windsor,” said Mr. Asher.

Psmith shook his head.

“I shouldn’t,” he said. “I speak in your best interests. Comrade Windsor is a man of the fiercest passions. He cannot brook interference. Were you to question the wisdom of his plans, there is no knowing what might not happen. He would be the first to regret any violent action, when once he had cooled off, but would that be any consolation to his victim? I think not. Of course, if you wish it, I could arrange a meeting——”

Mr. Asher said no, he thought it didn’t matter.

“I guess I can wait,” he said.

“That,” said Psmith approvingly, “is the right spirit. Wait. That is the watch-word. And now,” he added, rising, “I wonder if a bit of lunch somewhere might not be a good thing? We have had an interesting but fatiguing little chat. Our tissues require restoring. If you gentlemen would care to join me——”

Ten minutes later the company was seated in complete harmony round a table at the Knickerbocker. Psmith, with the dignified bonhomie of a seigneur of the old school, was ordering the wine; while B. Henderson Asher, brimming over with good-humour, was relating to an attentive circle an anecdote which should have appeared in his next instalment of “Moments of Mirth.”

HEN Psmith returned to the office, he found

Billy Windsor in the doorway, just parting from a thick-set young man, who

seemed to be expressing his gratitude to the editor for some good turn. He was

shaking him warmly by the hand.

HEN Psmith returned to the office, he found

Billy Windsor in the doorway, just parting from a thick-set young man, who

seemed to be expressing his gratitude to the editor for some good turn. He was

shaking him warmly by the hand.

Psmith stood aside to let him pass.

“An old college chum, Comrade Windsor?” he asked.

“That was Kid Brady.”

“The name is unfamiliar to me. Another contributor?”

“He’s from my part of the country—Wyoming. He wants to fight any one in the world at a hundred and thirty-three pounds.”

“We all have our hobbies. Comrade Brady appears to have selected a somewhat exciting one. He would find stamp-collecting less exacting.”

“It hasn’t given him much excitement so far, poor chap,” said Billy Windsor. “He’s in the championship class, and here he has been pottering about New York for a month without being able to get a fight. It’s always the way in this rotten east,” continued Billy, warming up as was his custom when discussing a case of oppression and injustice. “It’s all graft here. You’ve got to let half a dozen brutes dip into every dollar you earn, or you don’t get a chance. If the kid had a manager, he’d get all the fights he wanted. And the manager would get nearly all the money. I’ve told him that we will back him up.”

“You have hit it, Comrade Windsor,” said Psmith with enthusiasm. “Cosy Moments shall be Comrade Brady’s manager. We will give him a much-needed boost up in our columns. A sporting section is what the paper requires more than anything.”

“If things go on as they’ve started, what it will require still more will be a fighting-editor. Pugsy tells me you had visitors while I was out.”

“A few,” said Psmith. “One or two very entertaining fellows. Comrades Asher, Philpotts, and others. I have just been giving them a bite of lunch at the Knickerbocker.”

“Lunch!”

“A most pleasant little lunch. We are now as brothers. I fear I have made you perhaps a shade unpopular with our late contributors; but these things must be. We must clench our teeth and face them manfully. If I were you, I think I should not drop in at the house of Comrade Asher and the rest to take pot-luck for some little time to come. In order to soothe the squad I was compelled to curse you to some extent.”

“Don’t mind me.”

“I think I may say I didn’t.”

“Say, look here, you must charge up the price of that lunch to the office. Necessary expenses, you know.”

“I could not dream of doing such a thing, Comrade Windsor. The whole affair was a great treat to me. I have few pleasures. Comrade Asher alone was worth the money. I found his society intensely interesting. I have always believed in the Darwinian theory. Comrade Asher confirmed my views.”

They went into the inner office. Psmith removed his hat and coat.

“And now once more to work,” he said. “Psmith, the flaneur of Fifth Avenue, ceases to exist. In his place we find Psmith, the hard-headed sub-editor. Be so good as to indicate a job of work for me, Comrade Windsor. I am champing at my bit.”

Billy Windsor sat down, and lit his pipe.

“What we want most,” he said thoughtfully, “is some big topic. That’s the only way to get a paper going. Look at Everybody’s Magazine. They didn’t amount to a row of beans till Lawson started his ‘Frenzied Finance’ articles. Directly they began, the whole country was squealing for copies. Everybody’s put up their price from ten to fifteen cents, and now they lead the field.”

“The country must squeal for Cosy Moments,” said Psmith firmly. “I fancy I have a scheme which may not prove wholly scaly. Wandering yesterday with Comrade Jackson in a search for Fourth Avenue, I happened upon a spot called Pleasant Street. Do you know it?”

Billy Windsor nodded.

“I went down there once or twice when I was a reporter. It’s a beastly place.”

“It is a singularly beastly place. We went into one of the houses.”

“They’re pretty bad.”

“Who owns them?”

“I don’t know. Probably some millionaire. Those tenement houses are about as paying an investment as you can have.”

“Hasn’t anybody ever tried to do anything about them?”

“Not so far as I know. It’s pretty difficult to get at these fellows, you see. But they’re fierce, aren’t they, those houses!”

“What,” asked Psmith, “is the precise difficulty of getting at these merchants?”

“Well, it’s this way. There are all sorts of laws about the places, but any one who wants can get round them as easy as falling off a log. The law says a tenement-house is a building occupied by more than two families. Well, when there’s a fuss, all the man has to do is to clear out all the families but two. Then, when the inspector fellow comes along, and says, let’s say, ‘Where’s your running water on each floor? That’s what the law says you’ve got to have, and here are these people having to go downstairs and out of doors to fetch their water supplies,’ the landlord simply replies, ‘Nothing doing. This isn’t a tenement-house at all. There are only two families here.’ And when the fuss has blown over, back come the rest of the crowd, and things go on the same as before.”

“I see,” said Psmith. “A very cheery scheme.”

“Then there’s another thing. You can’t get hold of the man who’s really responsible, unless you’re prepared to spend thousands ferreting out evidence. The land belongs in the first place to some corporation or other. They lease it to a lessee. When there’s a fuss, they say they aren’t responsible, it’s up to the lessee. And he lies so low that you can’t find out who he is. It’s all just like the East. Everything in the East is as crooked as Pearl Street. If you want a square deal, you’ve got to come out Wyoming way.”

“The main problem, then,” said Psmith, “appears to be the discovery of the lessee, lad? Surely a powerful organ like Cosy Moments, with its vast ramifications, could bring off a thing like that?”

“I doubt it. We’ll try, anyway. There’s no knowing but what we may have luck.”

“Precisely,” said Psmith. “Full steam ahead, and trust to luck. The chances are that, if we go on long enough, we shall eventually arrive somewhere. After all, Columbus didn’t know that America existed when he set out. All he knew was some highly interesting fact about an egg. What that was, I do not at the moment recall, but it bucked Columbus up like a tonic. It made him fizz ahead like a two-year-old. The facts which will nerve us to effort are two. In the first place, we know that there must be some one at the bottom of the business. Secondly, as there appears to be no law of libel whatsoever in this great and free country, we shall be enabled to haul up our slacks with a considerable absence of restraint.”

“Sure,” said Billy Windsor. “Which of us is going to write the first article?”

“You may leave it to me, Comrade Windsor. I am no hardened old journalist, I fear, but I have certain qualifications for the post. A young man once called at the office of a certain newspaper, and asked for a job. ‘Have you any special line?’ asked the editor. ‘Yes,’ said the bright lad, ‘I am rather good at invective.’ ‘Any special kind of invective?’ queried the man up top. ‘No,’ replied our hero, ‘just general invective.’ Such is my own case, Comrade Windsor. I am a very fair purveyor of good, general invective. And as my visit to Pleasant Street is of such recent date, I am tolerably full of my subject. Taking full advantage of the benevolent laws of this country governing libel, I fancy I will produce a screed which will make this anonymous lessee feel as if he had inadvertently seated himself upon a tin-tack. Give me pen and paper, Comrade Windsor, instruct Comrade Maloney to suspend his whistling till such time as I am better able to listen to it; and I think we have got a success.”

HERE was once an editor of a paper in the Far West who was

sitting at his desk, musing pleasantly of life, when a bullet crashed through

the window and embedded itself in the wall at the back of his head. A happy

smile lit up the editor’s face. “Ah,” he said complacently, “I knew that

Personal column of ours was going to be a success!”

HERE was once an editor of a paper in the Far West who was

sitting at his desk, musing pleasantly of life, when a bullet crashed through

the window and embedded itself in the wall at the back of his head. A happy

smile lit up the editor’s face. “Ah,” he said complacently, “I knew that

Personal column of ours was going to be a success!”

What the bullet was to the Far West editor, the visit of Mr. Francis Parker to the offices of Cosy Moments was to Billy Windsor.

It occurred in the third week of the new régime of the paper. Cosy Moments, under its new management, had bounded ahead like a motor-car when the throttle is opened. Incessant work had been the order of the day. Billy Windsor’s hair had become more dishevelled than ever, and even Psmith had at moments lost a certain amount of his dignified calm. Sandwiched in between the painful case of Kid Brady and the matter of the tenements, which formed the star items of the paper’s contents, was a mass of bright reading dealing with the events of the day. Billy Windsor’s newspaper friends had turned in some fine, snappy stuff in their best Yellow Journal manner, relating to the more stirring happenings in the city. Psmith, who had constituted himself guardian of the literary and dramatic interests of the paper, had employed his gift of general invective to considerable effect, as was shown by a conversation between Master Maloney and a visitor one morning, heard through the open door.

“I wish to see the editor of this paper,” said the visitor.

“Editor not in,” said Master Maloney, untruthfully.

“Ha! Then when he returns I wish you to give him a message.”

“Sure.”

“I am Aubrey Bodkin, of the National Theatre. Give him my compliments, and tell him that Mr. Bodkin does not lightly forget.”

An unsolicited testimonial which caused Psmith the keenest satisfaction.

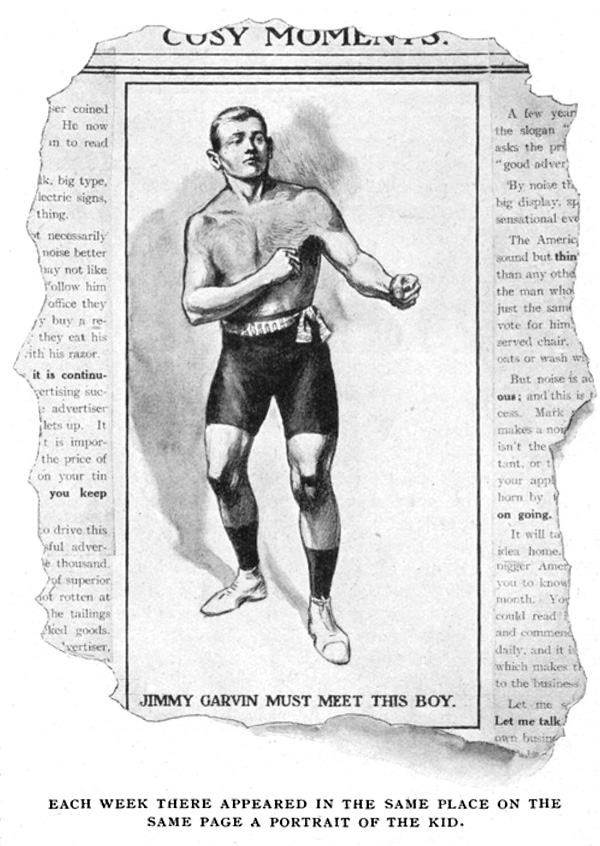

The section of the paper devoted to Kid Brady was attractive to all those with sporting blood in them. Each week there appeared in the same place on the same page a portrait of the Kid, looking moody and important, in an attitude of self-defence, and under the portrait the legend, “Jimmy Garvin must meet this boy.” Jimmy was the present holder of the light-weight title. He had won it a year before, and since then had confined himself to smoking cigars as long as walking-sticks and appearing nightly as the star in a music-hall sketch entitled “A Fight for Honour.” His reminiscences were appearing weekly in a Sunday paper. It was this that gave Psmith the idea of publishing Kid Brady’s autobiography in Cosy Moments, an idea which made the Kid his devoted adherent from then on. Like most pugilists, the Kid had a passion for bursting into print, and his life had been saddened up to the present by the refusal of the press to publish his reminiscences. To appear in print is the fighter’s accolade. It signifies that he has arrived. Psmith extended the hospitality of page four of Cosy Moments to Kid Brady, and the latter leaped at the chance. He was grateful to Psmith for not editing his contributions. Other pugilists, contributing to other papers, groaned under the supervision of a member of the staff who cut out their best passages and altered the rest into Addisonian English. The readers of Cosy Moments got Kid Brady raw.

“Comrade Brady,” said Psmith to Billy, “has a singularly pure and pleasing style. It is bound to appeal powerfully to the many-headed. Listen to this bit. Our hero is fighting Battling Jack Benson in that eminent artist’s native town of Louisville, and the citizens have given their native son the Approving Hand, while receiving Comrade Brady with chilly silence. Here is the Kid on the subject: ‘I looked around that house, and I seen I hadn’t a friend in it. And then the gong goes, and I says to myself how I has one friend, my poor old mother way out in Wyoming, and I goes in and mixes it, and then I seen Benson losing his goat, so I ups with an awful half-scissor hook to the plexus, and in the next round I seen Benson has a chunk of yellow, and I gets in with a hay-maker, and I picks up another sleep-producer from the floor and hands it him, and he takes the count all right.’ . . . Crisp, lucid, and to the point. That is what the public wants. If this does not bring Comrade Garvin up to the scratch, nothing will.”

But the feature of the paper was the “Tenement” series. It was late summer now, and there was nothing much going on in New York. The public was consequently free to take notice. The sale of Cosy Moments proceeded briskly. As Psmith had predicted, the change of policy had the effect of improving the sales to a marked extent. Letters of complaint from old subscribers poured into the office daily. But, as Billy Windsor complacently remarked, they had paid their subscriptions, so that the money was safe whether they read the paper or not. And, meanwhile, a large new public had sprung up and was growing every week. Advertisements came trooping in. Cosy Moments, in short, was passing through an era of prosperity undreamed of in its history.

“Young blood,” said Psmith nonchalantly, “young blood. That is the secret. A paper must keep up to date, or it falls behind its competitors in the race. Comrade Wilberfloss’ methods were possibly sound, but too limited and archaic. They lacked ginger. We of the younger generation have our fingers more firmly on the public pulse. We read off the public’s unspoken wishes as if by intuition. We know the game from A to Z.”

At this moment Master Maloney entered, bearing in his hand a card.

“ ‘Francis Parker’?” said Billy, taking it. “Don’t know him.”

“Nor I,” said Psmith. “We make new friends daily.”

“He’s a guy with a tall-shaped hat,” volunteered Master Maloney, “an’ he’s wearin’ a dude suit an’ shiny shoes.”

“Comrade Parker,” said Psmith approvingly, “has evidently not been blind to the importance of a visit to Cosy Moments. He has dressed himself in his best. He has felt, rightly, that this is no occasion for the old straw hat and the baggy flannels. I would not have it otherwise. It is the right spirit. Shall we give him audience, Comrade Windsor?”

“I wonder what he wants.”

“That,” said Psmith, “we shall ascertain more clearly after a personal interview. Comrade Maloney, show the gentleman in. We can give him three and a quarter minutes.”

Pugsy withdrew.

Mr. Francis Parker proved to be a man who might have been any age between twenty-five and thirty-five. He had a smooth, clean-shaven face, and a cat-like way of moving. As Pugsy had stated in effect, he wore a tail-coat, trousers with a crease which brought a smile of kindly approval to Psmith’s face, and patent-leather boots of pronounced shininess. Gloves and a tall-hat, which he carried, completed an impressive picture.

He moved softly into the room.

“I wished to see the editor.”

Psmith waved a hand towards Billy.

“The treat has not been denied you,” he said. “Before you is Comrade Windsor, the Wyoming cracker-jack. He is our editor. I myself—I am Psmith—though but a subordinate, may also claim the title in a measure. Technically, I am but a sub-editor; but such is the mutual esteem in which Comrade Windsor and I hold each other that we may practically be said to be inseparable. We have no secrets from each other. You may address us both impartially. Will you sit for a space?”

He pushed a chair towards the visitor, who seated himself with the care inspired by a perfect trouser-crease. There was a momentary silence while he selected a spot on the table on which to place his hat.

“The style of the paper has changed greatly, has it not, during the past few weeks?” he said. “I have never been, shall I say, a constant reader of Cosy Moments, and I may be wrong. But is not its interest in current affairs a recent development?”

“You are very right,” responded Psmith. “Comrade Windsor, a man of alert and restless temperament, felt that a change was essential if Cosy Moments was to lead public thought. Comrade Wilberfloss’ methods were good in their way. I have no quarrel with Comrade Wilberfloss. But he did not lead public thought. He catered exclusively for children with water on the brain, and men and women with solid ivory skulls. Comrade Windsor, with a broader view, feels that there are other and larger publics. He refuses to content himself with ladling out a weekly dole of mental predigested breakfast food. He provides meat. He——”

“Then—excuse me—” said Mr. Parker, turning to Billy, “You, I take it, are responsible for this very vigorous attack on the tenement house owners?”

“You can take it I am,” said Billy.

Psmith interposed.

“We are both responsible, Comrade Parker. If any husky guy, as I fancy Master Maloney would phrase it, is anxious to aim a swift kick at the man behind those articles, he must distribute it evenly between Comrade Windsor and myself.”

“I see.” Mr. Parker paused. “They are—er—very outspoken articles,” he added.

“Warm stuff,” agreed Psmith. “Distinctly warm stuff.”

“May I speak frankly?” said Mr. Parker.

“Assuredly, Comrade Parker. There must be no secrets, no restraint between us. We would not have you go away and say to yourself, ‘Did I make my meaning clear? Was I too elusive?’ Say on.”

“I am speaking in your best interests.”

“Who would doubt it, Comrade Parker? Nothing has buoyed us up more strongly during the hours of doubt through which we have passed than the knowledge that you wish us well.”

Billy Windsor suddenly became militant. There was a feline smoothness about the visitor which had been jarring upon him ever since he first spoke. Billy was of the plains, the home of blunt speech, where you looked your man in the eye and said it quick. Mr. Parker was too bland for human consumption. He offended Billy’s honest soul.

“See here,” cried he, leaning forward, “what’s it all about? Let’s have it. If you’ve anything to say about those articles, say it right out. Never mind our best interests. We can look after them. Let’s have what’s worrying you.”

Psmith waved a deprecating hand.

“Do not let us be abrupt on this happy occasion. To me it is enough simply to sit and chat with Comrade Parker, irrespective of the trend of his conversation. Still, as time is money, and this is our busy day, possibly it might be as well, sir, if you unburdened yourself as soon as convenient. Have you come to point out some flaw in those articles? Do they fall short in any way of your standard for such work?”

Mr. Parker’s smooth face did not change its expression, but he came to the point.

“I should not go on with them, if I were you,” he said.

“Why?” demanded Billy.

“There are reasons why you should not,” said Mr. Parker.

“And there are reasons why we should.”

“Less powerful ones.”

There proceeded from Billy a noise not describable in words. It was partly a snort, partly a growl. It resembled more than anything else the preliminary sniffing snarl a bull-dog emits before he joins battle. Billy’s cow-boy blood was up. He was rapidly approaching the state of mind in which the men of the plains, finding speech unequal to the expression of their thoughts, reach for their guns.

Psmith intervened.

“We do not completely gather your meaning, Comrade Parker. I fear we must ask you to hand it to us with still more breezy frankness. Do you speak from purely friendly motives? Are you advising us to discontinue the articles merely because you fear that they will damage our literary reputation? Or are there other reasons why you feel that they could cease? Do you speak solely as a literary connoisseur? Is it the style or the subject-matter of which you disapprove?”

Mr. Parker leaned forward.

“The gentleman whom I represent——”

“Then this is no matter of your own personal taste? You are an emissary?”

“These articles are causing a certain inconvenience to the gentleman whom I represent. Or, rather, he feels that, if continued, they may do so.”

“You mean,” broke in Billy explosively, “that if we kick up enough fuss to make somebody start a commission to inquire into this rotten business, your friend who owns the private Hades we’re trying to get improved, will have to get busy and lose some of his money by making the houses fit to live in? Is that it?”

“It is not so much the money, Mr. Windsor, though, of course, the expense would be considerable. My employer is a wealthy man.”

“I bet he is,” said Billy disgustedly. “I’ve no doubt he makes a mighty good pile out of Pleasant Street.”

“It is not so much the money,” repeated Mr. Parker, “as the publicity involved. I speak quite frankly. There are reasons why my employer would prefer not to come before the public just now as the owner of the Pleasant Street property. I need not go into those reasons. It is sufficient to say that they are strong ones.”

“Well, he knows what to do, I guess. The moment he starts in to make those houses decent, the articles stop. It’s up to him.”

Psmith nodded.

“Comrade Windsor is correct. He has hit the mark and rung the bell. No conscientious judge would withhold from Comrade Windsor a cigar or a cocoanut, according as his private preference might dictate. That is the matter in a nutshell. Remove the reason for those very scholarly articles, and they cease.”

Mr. Parker shook his head.

“I fear that is not feasible. The expense of reconstructing the houses makes that impossible.”

“Then there’s no use in talking,” said Billy. “The articles will go on.”

Mr. Parker coughed. A tentative cough, suggesting that the situation was now about to enter upon a more delicate phase. Billy and Psmith waited for him to begin. From their point of view the discussion was over. If it was to be reopened on fresh lines, it was for their visitor to effect that reopening.

“Now, I’m going to be frank, gentlemen,” said he, as who should say, “We are all friends here. Let us be hearty.” “I’m going to put my cards on the table, and see if we can’t fix something up. Now, see here. We don’t want unpleasantness. You aren’t in this business for your healths, eh? You’ve got your living to make, just like everybody else, I guess. Well, see here. This is how it stands. To a certain extant, I don’t mind admitting, seeing that we’re being frank with one another, you two gentlemen have got us—that’s to say, my employer—in a cleft stick. Frankly, those articles are beginning to attract attention, and if they go on there’s going to be a lot of inconvenience for my employer. That’s clear, I reckon. Well, now, here’s a square proposition. How much do you want to stop those articles? That’s straight. I’ve been frank with you, and I want you to be frank with me. What’s your figure? Name it, and, if it’s not too high, I guess we needn’t quarrel.”

He looked expectantly at Billy. Billy’s eyes were bulging. He struggled for speech. He had got as far as “Say!” when Psmith interrupted him. Psmith, gazing sadly at Mr. Parker through his monocle, spoke quietly, with the restrained dignity of some old Roman senator dealing with the enemies of the Republic.

“Comrade Parker,” he said, “I fear that you have allowed constant communication with the conscienceless commercialism of this worldly city to undermine your moral sense. It is useless to dangle rich bribes before our eyes. Cosy Moments cannot be muzzled. You doubtless mean well, according to your—if I may say so—somewhat murky lights, but we are not for sale, except at ten cents weekly. From the hills of Maine to the Everglades of Florida, from Sandy Hook to San Francisco, from Portland, Oregon, to Melonsquashville, Tennessee, one sentence is in every man’s mouth. And what is that sentence? I give you three guesses. You give it up? It is this: ‘Cosy Moments cannot be muzzled!’ ”

Mr. Parker rose.

“There’s nothing more to be done then,” he said.

“Nothing,” agreed Psmith, “except to make a noise like a hoop and roll away.”

“And do it quick,” yelled Billy, exploding like a fire-cracker.

Psmith bowed.

“Speed,” he admitted, “would be no bad thing. Frankly—if I may borrow the expression—your square proposition has wounded us. I am a man of powerful self-restraint, one of those strong, silent men, and I can curb my emotions. But I fear that Comrade Windsor’s generous temperament may at any moment prompt him to start throwing ink-pots. And in Wyoming his deadly aim with the ink-pot won him among the admiring cowboys the sobriquet of Crack-Shot Cuthbert. As man to man, Comrade Parker, I should advise you to bound swiftly away.”

“I’m going,” said Mr. Parker, picking up his hat. “And I’ll give you a piece of advice, too. Those articles are going to be stopped, and if you’ve any sense between you, you’ll stop them yourselves before you get hurt. That’s all I’ve got to say, and that goes.”

He went out, closing the door behind him with a bang that added emphasis to his words.

“To men of nicely poised nervous organisation such as ourselves, Comrade Windsor,” said Psmith, smoothing his waistcoat thoughtfully, “these scenes are acutely painful. We wince before them. Our ganglions quiver like cinematographs. Gradually recovering command of ourselves, we review the situation. Did our visitor’s final remarks convey anything definite to you? Were they the mere casual badinage of a parting guest, or was there something solid behind them?”

Billy Windsor was looking serious.

“I guess he meant it all right. He’s evidently working for somebody pretty big, and that sort of man would have a pull with all kinds of Thugs. We shall have to watch out. Now that they find we can’t be bought, they’ll try the other way. They mean business sure enough. But, by George, let ’em! We’re up against a big thing, and I’m going to see it through if they put every gang in New York on to us.”

“Precisely, Comrade Windsor. Cosy Moments, as I have had occasion to observe before, cannot be muzzled.”

“That’s right,” said Billy Windsor. “And,” he added, with the contented look the Far West editor must have worn as the bullet came through the window, “we must have got them scared, or they wouldn’t have shown their hand that way. I guess we’re making a hit. Cosy Moments is going some now.”

(To be continued)

Madame Eulalie’s Rare Plums

Madame Eulalie’s Rare Plums