The Captain, March 1910

* Former tales about “Psmith” are “The Lost Lambs” and “The New Fold,” in Vols. XIX and XX of The Captain.

R. JARVIS WAS as good as his word. On the

following morning, at ten o’clock to the minute, he made his appearance at the

office of Cosy Moments, his fore-lock more than usually well oiled in

honour of the occasion, and his right coat-pocket bulging in a manner that

betrayed to the initiated eye the presence of the faithful “canister.” With him,

in addition to his revolver, he brought a long, thin young man who wore under

his brown tweed coat a blue-and-red striped jersey. Whether he brought him as an

ally in case of need or merely as a kindred soul with whom he might commune

during his vigil, was not ascertained.

R. JARVIS WAS as good as his word. On the

following morning, at ten o’clock to the minute, he made his appearance at the

office of Cosy Moments, his fore-lock more than usually well oiled in

honour of the occasion, and his right coat-pocket bulging in a manner that

betrayed to the initiated eye the presence of the faithful “canister.” With him,

in addition to his revolver, he brought a long, thin young man who wore under

his brown tweed coat a blue-and-red striped jersey. Whether he brought him as an

ally in case of need or merely as a kindred soul with whom he might commune

during his vigil, was not ascertained.

Pugsy, startled out of his wonted calm by the arrival of this distinguished company, observed the pair, as they passed through into the inner office, with protruding eyes, and sat speechless for a full five minutes. Psmith received the newcomers in the editorial sanctum with courteous warmth. Mr. Jarvis introduced his colleague.

“Thought I’d bring him along. Long Otto’s his monaker.”

“You did very rightly, Comrade Jarvis,” Psmith assured him. “Your unerring instinct did not play you false when it told you that Comrade Otto would be as welcome as the flowers in May. With Comrade Otto I fancy we shall make a combination which will require a certain amount of tackling.”

Mr. Jarvis confirmed this view. Long Otto, he affirmed, was no rube, but a scrapper from Biffville-on-the-Slosh. The hardiest hooligan would shrink from introducing rough-house proceedings into a room graced by the combined presence of Long Otto and himself.

“Then,” said Psmith, “I can go about my professional duties with a light heart. I may possibly sing a bar or two. You will find cigars in that box. If you and Comrade Otto will select one apiece and group yourselves tastefully about the room in chairs, I will start in to hit up a slightly spicy editorial on the coming election.”

Mr. Jarvis regarded the paraphernalia of literature on the table with interest. So did Long Otto, who, however, being a man of silent habit, made no comment. Throughout the séance and the events which followed it he confined himself to an occasional grunt. He seemed to lack other modes of expression. A charming chap, however.

“Is dis where youse writes up pieces fer de paper?” inquired Mr. Jarvis, eyeing the table.

“It is,” said Psmith. “In Comrade Windsor’s pre-dungeon days he was wont to sit where I am sitting now, while I bivouacked over there at the smaller table. On busy mornings you could hear our brains buzzing in Madison Square Garden. But wait! A thought strikes me.” He called for Pugsy.

“Comrade Maloney,” he said, “if the Editorial Staff of this paper were to give you a day off, could you employ it to profit?”

“Surest t’ing you know,” replied Pugsy with some fervour. “I’d take me goil to de Bronx Zoo.”

“Your girl?” said Psmith inquiringly. “I had heard no inkling of this, Comrade Maloney. I had always imagined you one of those strong, rugged, blood-and-iron men who were above the softer emotions. Who is she?”

“Aw, she’s a kid,” said Pugsy. “Her pa runs a delicatessen shop down our street. She ain’t a bad mutt,” added the ardent swain. “I’m her steady.”

“See that I have a card for the wedding, Comrade Maloney,” said Psmith, “and in the meantime take her to the Bronx, as you suggest.”

“Won’t youse be wantin’ me to-day?”

“Not to-day. You need a holiday. Unflagging toil is sapping your physique. Go up and watch the animals, and remember me very kindly to the Peruvian Llama, whom friends have sometimes told me I resemble in appearance. And if two dollars would in any way add to the gaiety of the jaunt——”

“Sure t’ing. T’anks, boss.”

“It occurred to me,” said Psmith, when he had gone, “that the probable first move of any enterprising Three Pointer who invaded this office would be to knock Comrade Maloney on the head to prevent his announcing him. Comrade Maloney’s services are too valuable to allow him to be exposed to unnecessary perils. Any visitors who call must find their way in for themselves. And now to work. Work, the what’s-its-name of the thingummy and the thing-um-a-bob of the what d’you- call-it.”

For about a quarter of an hour the only sound that broke the silence of the room was the scratching of Psmith’s pen and the musical expectoration of Messrs. Otto and Jarvis. Finally Psmith leaned back in his chair with a satisfied expression, and spoke.

“While, as of course you know, Comrade Jarvis,” he said, “there is no agony like the agony of literary composition, such toil has its compensations. The editorial I have just completed contains its measure of balm. Comrade Otto will bear me out in my statement that there is a subtle joy in the manufacture of the well-formed phrase. Am I not right, Comrade Otto?”

The long one gazed appealingly at Mr. Jarvis, who spoke for him.

“He’s a bit shy on handin’ out woids, is Otto,” he said.

Psmith nodded.

“I understand. I am a man of few words myself. All great men are like that. Von Moltke, Comrade Otto, and myself. But what are words? Action is the thing. That is the cry. Action. If that is Comrade Otto’s forte, so much the better, for I fancy that action rather than words is what we may be needing in the space of about a quarter of a minute. At least, if the footsteps I hear without are, as I suspect, those of our friends of the Three Points.”

Jarvis and Long Otto turned towards the door. Psmith was right. Some one was moving stealthily in the outer office. Judging from the sound, more than one person.

“It is just as well,” said Psmith softly, “that Comrade Maloney is not at his customary post. Now, in about a quarter of a minute, as I said,—Aha!”

The handle of the door began to revolve slowly and quietly. The next moment three figures tumbled into the room. It was evident that they had not expected to find the door unlocked, and the absence of resistance when they applied their weight had had surprising effects. Two of the three did not pause in their career till they cannoned against the table. The third, who was holding the handle, was more fortunate.

Psmith rose with a kindly smile to welcome his guests.

“Why, surely!” he said in a pleased voice. “I thought I knew the face. Comrade Repetto, this is a treat. Have you come bringing me a new hat?”

The white-haired leader’s face, as he spoke, was within a few inches of his own. Psmith’s observant eye noted that the bruise still lingered on the chin where Kid Brady’s upper-cut had landed at their previous meeting.

“I cannot offer you all seats,” he went on, “unless you care to dispose yourselves upon the tables. I wonder if you know my friend, Mr. Bat Jarvis? And my friend, Mr. L. Otto? Let us all get acquainted on this merry occasion.”

The three invaders had been aware of the presence of the great Bat and his colleague for some moments, and the meeting seemed to be causing them embarrassment. This may have been due to the fact that both Mr. Jarvis and Mr. Otto had produced and were toying meditatively with distinctly ugly-looking pistols.

Mr. Jarvis spoke.

“Well,” he said, “what’s doin’?”

Mr. Repetto, to whom the remark was directly addressed, appeared to have some difficulty in finding a reply. He shuffled his feet, and looked at the floor. His two companions seemed equally at a loss.

“Goin’ to start any rough stuff?” inquired Mr. Jarvis casually.

“The cigars are on the table,” said Psmith hospitably. “Draw up your chairs, and let’s all be jolly. I will open the proceedings with a song.”

In a rich baritone, with his eyeglass fixed the while on Mr. Repetto, he proceeded to relieve himself of the first verse of “I only know I love thee.”

“Chorus, please,” he added, as he finished. “Come along, Comrade Repetto. Why this shrinking coyness? Fling out your chest, and cut loose.”

But Mr. Repetto’s eye was fastened on Mr. Jarvis’s revolver. The sight apparently had the effect of quenching his desire for song.

“ ‘Lov’ muh, ahnd ther world is—ah—mine!’ ” concluded Psmith.

He looked round the assembled company.

“Comrade Otto,” he observed, “will now recite that pathetic little poem ‘Baby’s Sock is now a Blue-bag.’ Pray, gentlemen, silence for Comrade Otto.”

He looked inquiringly at the long youth, who remained mute. Psmith clicked his tongue regretfully.

“Comrade Jarvis,” he said, “I fear that as a smoking-concert this is not going to be a success. I understand, however. Comrade Repetto and his colleagues have come here on business, and nothing will make them forget it. Typical New York men of affairs, they close their minds to all influences that might lure them from their business. Let us get on, then. What did you wish to see me about, Comrade Repetto?”

Mr. Repetto’s reply was unintelligible.

Mr. Jarvis made a suggestion.

“Youse had better beat it,” he said.

Long Otto grunted sympathy with this advice.

“And youse had better go back to Spider Reilly,” continued Mr. Jarvis, “and tell him that there’s nothin’ doin’ in the way of rough-house wit dis gent here.” He indicated Psmith, who bowed. “And you can tell de Spider,” went on Bat with growing ferocity, “dat next time he gits gay and starts in to shoot guys in me dance-joint I’ll bite de head off’n him. See? Does dat go? If he t’inks his little two-by-four gang can put it across de Groome Street, he can try. Dat’s right. An’ don’t fergit dis gent here and me is pals, and any one dat starts anyt’ing wit dis gent is going to have to git busy wit me. Does dat go?”

Psmith coughed, and shot his cuffs.

“I do not know,” he said, in the manner of a chairman addressing a meeting, “that I have anything to add to the very well-expressed remarks of my friend, Comrade Jarvis. He has, in my opinion, covered the ground very thoroughly and satisfactorily. It now only remains for me to pass a vote of thanks to Comrade Jarvis and to declare this meeting at an end.”

“Beat it,” said Mr. Jarvis, pointing to the door.

The delegation then withdrew.

“I am very much obliged,” said Psmith, “for your courtly assistance, Comrade Jarvis. But for you I do not care to think with what a splash I might not have been immersed in the gumbo. Thank you, Comrade Jarvis. And you, Comrade Otto.”

“Aw chee!” said Mr. Jarvis, handsomely dismissing the matter. Mr. Otto kicked the leg of the table, and grunted.

For half an hour after the departure of the Three Pointers Psmith chatted amiably to his two assistants on matters of general interest. The exchange of ideas was somewhat one-sided, though Mr. Jarvis had one or two striking items of information to impart, notably some hints on the treatment of fits in kittens.

At the end of this period the conversation was once more interrupted by the sound of movements in the outer office.

“If dat’s dose stiffs come back—” began Mr. Jarvis, reaching for his revolver.

“Stay your hand, Comrade Jarvis,” said as a sharp knock sounded on the door. “I do not think it can be our late friends. Comrade Repetto’s knowledge of the usages of polite society is too limited, I fancy, to prompt him to knock on doors. Come in.”

The door opened. It was not Mr. Repetto or his colleagues, but another old friend. No other, in fact, than Mr. Francis Parker, he who had come as an embassy from the man up top in the very beginning of affairs, and had departed, wrathful, mouthing declarations of war. As on his previous visit, he wore the dude suit, the shiny shoes, and the tall-shaped hat.

“Welcome, Comrade Parker,” said Psmith. “It is too long since we met. Comrade Jarvis I think you know. If I am right, that is to say, in supposing that it was you who approached him at an earlier stage in the proceedings with a view to engaging his sympathetic aid in the great work of putting Comrade Windsor and myself out of business. The gentleman on your left is Comrade Otto.”

Mr. Parker was looking at Bat in bewilderment. It was plain that he had not expected to find Psmith entertaining such company.

“Did you come purely for friendly chit-chat, Comrade Parker,” inquired Psmith, “or was there, woven into the social motives of your call, a desire to talk business of any kind?”

“My business is private. I didn’t expect a crowd.”

“Especially of ancient friends such as Comrade Jarvis. Well, well, you are breaking up a most interesting little symposium. Comrade Jarvis, I think I shall be forced to postpone our very entertaining discussion of fits in kittens till a more opportune moment. Meanwhile, as Comrade Parker wishes to talk over some private business——”

Bat Jarvis rose.

“I’ll beat it,” he said.

“Reluctantly, I hope, Comrade Jarvis. As reluctantly as I hint that I would be alone. If I might drop in some time at your private residence?”

“Sure,” said Mr. Jarvis warmly.

“Excellent. Well, for the present, good-bye. And many thanks for your invaluable co-operation.”

“Aw chee!” said Mr. Jarvis.

“And now, Comrade Parker,” said Psmith, when the door had closed, “let her rip. What can I do for you?”

“You seem to be all to the merry with Bat Jarvis,” observed Mr. Parker.

“The phrase exactly expresses it, Comrade Parker. I am as a tortoiseshell kitten to him. But, touching your business?”

Mr. Parker was silent for a moment.

“See here,” he said at last, “aren’t you going to be good? Say, what’s the use of keeping on at this fool game? Why not quit it before you get hurt?”

Psmith smoothed his waistcoat reflectively.

“I may be wrong, Comrade Parker,” he said, “but it seems to me that the chances of my getting hurt are not so great as you appear to imagine. The person who is in danger of getting hurt seems to me to be the gentleman whose name is on that paper which is now in my possession.”

“Where is it?” demanded Mr. Parker quickly.

Psmith eyed him benevolently.

“If you will pardon the expression, Comrade Parker,” he said, “ ‘Aha!’ Meaning that I propose to keep that information to myself.”

Mr. Parker shrugged his shoulders.

“You know your own business, I guess.”

Psmith nodded.

“You are absolutely correct, Comrade Parker. I do. Now that Cosy Moments has our excellent friend Comrade Jarvis on its side, are you not to a certain extent among the Blenheim Oranges? I think so. I think so.”

As he spoke there was a rap at the door. A small boy entered. In his hand was a scrap of paper.

“Guy asks me give dis to gazebo named Smiff,” he said.

“There are many gazebos of that name, my lad. One of whom I am which, as Artemus Ward was wont to observe. Possibly the missive is for me.”

He took the paper. It was dated from an address on the East Side.

“Dear Smith,” it ran. “Come here as quick as you can, and bring some money. Explain when I see you.”

It was signed “W. W.”

So Billy Windsor had fulfilled his promise. He had escaped.

A feeling of regret for the futility of the thing was Psmith’s first emotion. Billy could be of no possible help in the campaign at its present point. All the work that remained to be done could easily be carried through without his assistance. And by breaking out from the Island he had committed an offence which was bound to carry with it serious penalties. For the first time since his connection with Cosy Moments began Psmith was really disturbed.

He turned to Mr. Parker.

“Comrade Parker,” he said, “I regret to state that this office is now closing for the day. But for this, I should be delighted to sit chatting with you. As it is——”

“Very well,” said Mr. Parker. “Then you mean to go on with this business?”

“Though it snows, Comrade Parker.”

They went out into the street, Psmith thoughtful and hardly realising the other’s presence. By the side of the pavement a few yards down the road a taximeter-cab was standing. Psmith hailed it.

Mr. Parker was still beside him. It occurred to Psmith that it would not do to let him hear the address Billy Windsor had given in his note.

“Turn and go on down the street,” he said to the driver.

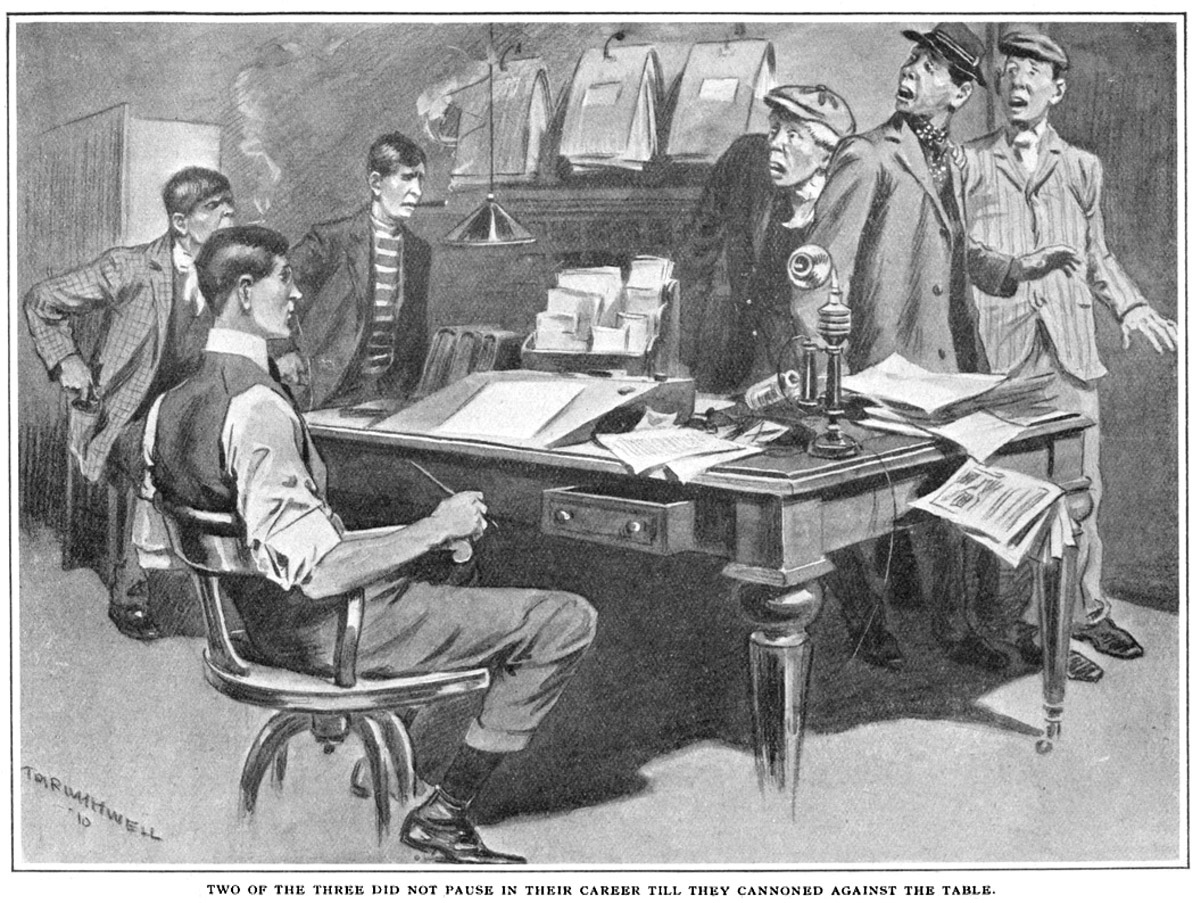

He had taken his seat and was closing the door, when it was snatched from his grasp and Mr. Parker darted on to the seat opposite. The next moment the cab had started up the street instead of down, and the hard muzzle of a revolver was pressing against Psmith’s waistcoat.

“Now what?” said Mr. Parker smoothly, leaning back with the pistol resting easily on his knee.

CHAPTER XXVI.

a friend in need.

HE point is well taken,” said Psmith thoughtfully.

HE point is well taken,” said Psmith thoughtfully.

“You think so?” said Mr. Parker.

“I am convinced of it.”

“Good. But don’t move. Put that hand back where it was.”

“You think of everything, Comrade Parker.”

He dropped his hand on to the seat, and remained silent for a few moments. The taxi-cab was buzzing along up Fifth Avenue now. Looking towards the window, Psmith saw that they were nearing the park. The great white mass of the Plaza Hotel showed up on the left.

“Did you ever stop at the Plaza, Comrade Parker?”

“No,” said Mr. Parker shortly.

“Don’t bite at me, Comrade Parker. Why be brusque on so joyous an occasion? Better men than us have stopped at the Plaza. Ah, the Park! How fresh the leaves, Comrade Parker, how green the herbage! Fling your eye at yonder grassy knoll.”

He raised his hand to point. Instantly the revolver was against his waistcoat, making an unwelcome crease in that immaculate garment.

“I told you to keep that hand where it was.”

“You did, Comrade Parker, you did. The fault,” said Psmith handsomely, “was mine. Entirely mine. Carried away by my love of nature, I forgot. It shall not occur again.”

“It had better not,” said Mr. Parker unpleasantly. “If it does, I’ll blow a hole through you.”

Psmith raised his eyebrows.

“That, Comrade Parker,” he said, “is where you make your error. You would no more shoot me in the heart of the metropolis than, I trust, you would wear a made-up tie with evening dress. Your skin, however unhealthy to the eye of the casual observer, is doubtless precious to yourself, and you are not the man I take you for if you would risk it purely for the momentary pleasure of plugging me with a revolver. The cry goes round criminal circles in New York, ‘Comrade Parker is not such a fool as he looks.’ Think for a moment what would happen. The shot would ring out, and instantly bicycle-policemen would be pursuing this taxi-cab with the purposeful speed of greyhounds trying to win the Waterloo Cup. You would be headed off and stopped. Ha! What is this? Psmith, the People’s Pet, weltering in his gore? Death to the assassin! I fear nothing could save you from the fury of the mob, Comrade Parker. I seem to see them meditatively plucking you limb from limb. ‘She loves me!’ Off comes an arm. ‘She loves me not.’ A leg joins the little heap of limbs on the ground. That is how it would be. And what would you have left out of it? Merely, as I say, the momentary pleasure of potting me. And it isn’t as if such a feat could give you the thrill of successful marksmanship. Anybody could hit a man with a pistol at an inch and a quarter. I fear you have not thought this matter out with sufficient care, Comrade Parker. You said to yourself, ‘Happy thought, I will kidnap Psmith!’ and all your friends said, ‘Parker is the man with the big brain!’ But now, while it is true that I can’t get out, you are moaning, ‘What on earth shall I do with him, now that I have got him?’ ”

“You think so, do you?”

“I am convinced of it. Your face is contorted with the anguish of mental stress. Let this be a lesson to you, Comrade Parker, never to embark on any enterprise of which you do not see the end.”

“I guess I see the end of this all right.”

“You have the advantage of me then, Comrade Parker. It seems to me that we have nothing before us but to go on riding about New York till you feel that my society begins to pall.”

“You figure you’re clever, I guess.”

“There are few brighter brains in this city, Comrade Parker. But why this sudden tribute?”

“You reckon you’ve thought it all out, eh?”

“There may be a flaw in my reasoning, but I confess I do not at the moment see where it lies. Have you detected one?”

“I guess so.”

“Ah! And what is it?”

“You seem to think New York’s the only place on the map.”

“Meaning what, Comrade Parker?”

“It might be a fool trick to shoot you in the city as you say, but, you see, we aren’t due to stay in the city. This cab is moving on.”

“Like John Brown’s soul,” said Psmith, nodding. “I see. Then you propose to make quite a little tour in this cab?”

“You’ve got it.”

“And when we are out in the open country, where there are no witnesses, things may begin to move.”

“That’s it.”

“Then,” said Psmith heartily, “till that moment arrives what we must do is to entertain each other with conversation. You can take no step of any sort for a full half-hour, possibly more, so let us give ourselves up to the merriment of the passing instant. Are you good at riddles, Comrade Parker? How much wood would a wood-chuck chuck, assuming for purposes of argument that it was in the power of a wood-chuck to chuck wood?”

Mr. Parker did not attempt to solve this problem. He was sitting in the same attitude of watchfulness, the revolver resting on his knee. He seemed mistrustful of Psmith’s right hand, which was hanging limply at his side. It was from this quarter that he seemed to expect attack. The cab was bowling easily up the broad street, past rows on rows of high houses, all looking exactly the same. Occasionally, to the right, through a break in the line of buildings, a glimpse of the river could be seen.

Psmith resumed the conversation.

“You are not interested in wood-chucks, Comrade Parker? Well, well, many people are not. A passion for the flora and fauna of our forests is innate rather than acquired. Let us talk of something else. Tell me about your home-life, Comrade Parker. Are you married? Are there any little Parkers running about the house? When you return from this very pleasant excursion will baby voices crow gleefully, ‘Fahzer’s come home’?”

Mr. Parker said nothing.

“I see,” said Psmith with ready sympathy. “I understand. Say no more. You are unmarried. She wouldn’t have you. Alas, Comrade Parker! However, thus it is! We look around us, and what do we see? A solid phalanx of the girls we have loved and lost. Tell me about her, Comrade Parker. Was it your face or your manners at which she drew the line?”

Mr. Parker leaned forward with a scowl. Psmith did not move, but his right hand, as it hung, closed. Another moment and Mr. Parker’s chin would be in just the right position for a swift upper-cut. . . .

This fact appeared suddenly to dawn on Mr. Parker himself. He drew back quickly, and half raised the revolver. Psmith’s hand resumed its normal attitude.

“Leaving more painful topics,” said Psmith, “let us turn to another point. That note which the grubby stripling brought to me at the office purported to come from Comrade Windsor, and stated that he had escaped from Blackwell’s Island, and was awaiting my arrival at some address in the Bowery. Would you mind telling me, purely to satisfy my curiosity, if that note was genuine? I have never made a close study of Comrade Windsor’s handwriting, and in an unguarded moment I may have assumed too much.”

Mr. Parker permitted himself a smile.

“I guess you aren’t so clever after all,” he said. “The note was a fake all right.”

“And you had this cab waiting for me on the chance?”

Mr. Parker nodded.

“Sherlock Holmes was right,” said Psmith regretfully. “You may remember that he advised Doctor Watson never to take the first cab, or the second. He should have gone further, and urged him not to take cabs at all. Walking is far healthier.”

“You’ll find it so,” said Mr. Parker.

Psmith eyed him curiously.

“What are you going to do with me, Comrade Parker?” he asked.

Mr. Parker did not reply. Psmith’s eye turned again to the window. They had covered much ground since last he had looked at the view. They were off Manhattan Island now, and the houses were beginning to thin out. Soon, travelling at their present rate, they must come into the open country. Psmith relapsed into silence. It was necessary for him to think. He had been talking in the hope of getting the other off his guard; but Mr. Parker was evidently too keenly on the look-out. The hand that held the revolver never wavered. The muzzle, pointing in an upward direction, was aimed at Psmith’s waist. There was no doubt that a move on his part would be fatal. If the pistol went off, it must hit him. If it had been pointed at his head in the orthodox way he might have risked a sudden blow to knock it aside, but in the present circumstances that would be useless. There was nothing to do but wait.

The cab moved swiftly on. Now they had reached the open country. An occasional wooden shack was passed, but that was all. At any moment the climax of the drama might be reached. Psmith’s muscles stiffened for a spring. There was little chance of its being effective, but at least it would be better to put up some kind of a fight. And he had a faint hope that the suddenness of his movement might upset the other’s aim. He was bound to be hit somewhere. That was certain. But quickness might save him to some extent.

He braced his leg against the back of the cab. In another moment he would have sprung; but just then the smooth speed of the cab changed to a series of jarring bumps, each more emphatic than the last. It slowed down, then came to a halt. One of the tyres had burst.

There was a thud, as the chauffeur jumped down. They heard him fumbling in the tool-box. Presently the body of the machine was raised slightly as he got to work with the jack.

It was about a minute later that somebody in the road outside spoke.

“Had a break-down?” inquired the voice.

Psmith recognised it. It was the voice of Kid Brady.

CHAPTER XXVII.

psmith concludes his ride.

HE Kid, as he had stated to Psmith at their

last interview that he intended to do, had begun his training for his match with

Eddie Wood at White Plains, a village distant but a few miles from New York. It

was his practice to open a course of training with a little gentle road-work;

and it was while jogging along the highway a couple of miles from his training-camp, in company with the two thick-necked gentlemen who acted as his sparring-partners, that he had come upon the broken-down taxi-cab.

HE Kid, as he had stated to Psmith at their

last interview that he intended to do, had begun his training for his match with

Eddie Wood at White Plains, a village distant but a few miles from New York. It

was his practice to open a course of training with a little gentle road-work;

and it was while jogging along the highway a couple of miles from his training-camp, in company with the two thick-necked gentlemen who acted as his sparring-partners, that he had come upon the broken-down taxi-cab.

If this had happened after his training had begun in real earnest, he would have averted his eyes from the spectacle, however alluring, and continued on his way without a pause. But now, as he had not yet settled down to genuine hard work, he felt justified in turning aside and looking into the matter. The fact that the chauffeur, who seemed to be a taciturn man, lacking the conversational graces, manifestly objected to an audience, deterred him not at all. One cannot have everything in this world, and the Kid and his attendant thick-necks were content to watch the process of mending the tyre, without demanding the additional joy of sparkling small-talk from the man in charge of the operations.

“Guy’s had a break-down, sure,” said the first of the thick-necks.

“Surest thing you know,” agreed his colleague.

“Seems to me the tyre’s punctured,” said the Kid.

All three concentrated their gaze on the machine

“Kid’s right,” said thick-neck number one. “Guy’s been an’ bust a tyre.”

“Surest thing you know,” said thick-neck number two.

They observed the perspiring chauffeur in silence for a while.

“Wonder how he did that, now?” speculated the Kid.

“Guy ran over a nail, I guess,” said thick-neck number one.

“Surest thing you know,” said the other, who, while perhaps somewhat lacking in the matter of original thought, was a most useful fellow to have by one. A sort of Boswell.

“Did you run over a nail?” the Kid inquired of the chauffeur.

The chauffeur ignored the question.

“This is his busy day,” said the first thick-neck with satire. “Guy’s too full of work to talk to us.”

“Deaf, shouldn’t wonder,” surmised the Kid. “Say, wonder what he’s doin’ with a taxi so far out of the city.”

“Some guy tells him to drive him out here, I guess. Say, it’ll cost him something, too. He’ll have to strip off a few from his roll to pay for this.”

Psmith, in the interior of the cab, glanced at Mr. Parker.

“You heard, Comrade Parker? He is right, I fancy. The bill——”

Mr. Parker dug viciously at him with the revolver.

“Keep quiet,” he whispered, “or you’ll get hurt.”

Psmith suspended his remarks.

Outside, the conversation had begun again.

“Pretty rich guy inside,” said the Kid, following up his companion’s train of thought. “I’m goin’ to rubber in at the window.”

Psmith, meeting Mr. Parker’s eye, smiled pleasantly. There was no answering smile on the other’s face.

There came the sound of the Kid’s feet grating on the road as he turned; and as he heard it Mr. Parker, that eminent tactician, for the first time lost his head. With a vague idea of screening Psmith from the eyes of the man in the road he half rose. For an instant the muzzle of the pistol ceased to point at Psmith’s waistcoat. It was the very chance Psmith had been waiting for. His left hand shot out, grasped the other’s wrist, and gave it a sharp wrench. The revolver went off with a deafening report, the bullet passing through the back of the cab; then fell to the floor, as the fingers lost their hold. The next moment Psmith’s right fist, darting upwards, took Mr. Parker neatly under the angle of the jaw.

The effect was instantaneous. Psmith had risen from his seat as he delivered the blow, and it consequently got the full benefit of his weight, which was not small. Mr. Parker literally crumpled up. His head jerked back, then fell limply on his chest. He would have slipped to the floor had not Psmith pushed him on to the seat.

The interested face of the Kid appeared at the window. Behind him could be seen portions of the faces of the two thick-necks.

“Ah, Comrade Brady!” said Psmith genially. “I heard your voice, and was hoping you might look in for a chat.”

“What’s doin’, Mr. Smith?” queried the excited Kid.

“Much, Comrade Brady, much. I will tell you all anon. Meanwhile, however, kindly knock that chauffeur down and sit on his head. He’s a bad person.”

“De guy’s beat it,” volunteered the first thick-neck.

“Surest thing you know,” said the other.

“What’s been doin’, Mr. Smith?” asked the Kid.

“I’ll tell you about it as we go, Comrade Brady,” said Psmith, stepping into the road. “Riding in a taxi is pleasant provided it is not overdone. For the moment I have had sufficient. A bit of walking will do me good.”

“What are you going to do with this guy, Mr. Smith?” asked the Kid, pointing to Parker, who had begun to stir slightly.

Psmith inspected the stricken one gravely.

“I have no use for him, Comrade Brady,” he said. “Our ride together gave me as much of his society as I desire for to-day. Unless you or either of your friends are collecting Parkers, I propose that we leave him where he is. We may as well take the gun, however. In my opinion, Comrade Parker is not the proper man to have such a weapon. He is too prone to go firing it off in any direction at a moment’s notice, causing inconvenience to all.” He groped on the floor of the cab for the revolver. “Now, Comrade Brady,” he said, straightening himself up, “I am at your disposal. Shall we be pushing on?”

It was late in the evening when Psmith returned to the metropolis, after a pleasant afternoon at the Brady training-camp. The Kid, having heard the details of the ride, offered once more to abandon his match with Eddie Wood, but Psmith would not hear of it. He was fairly satisfied that the opposition had fired their last shot, and that their next move would be to endeavour to come to terms. They could not hope to catch him off his guard a second time, and, as far as hired assault and battery were concerned, he was as safe in New York, now that Bat Jarvis had declared himself on his side, as he would have been in the middle of a desert. What Bat said was law on the East Side. No hooligan, however eager to make money, would dare to act against a protégé of the Groome Street leader.

The only flaw in Psmith’s contentment was the absence of Billy Windsor. On this night of all nights the editorial staff of Cosy Moments should have been together to celebrate the successful outcome of their campaign. Psmith dined alone, his enjoyment of the rather special dinner which he felt justified in ordering in honour of the occasion somewhat diminished by the thought of Billy’s hard case. He had seen Mr. William Collier in The Man from Mexico, and that had given him an understanding of what a term of imprisonment on Blackwell’s Island meant. Billy, during these lean days, must be supporting life on bread, bean soup, and water. Psmith, toying with the hors d’œuvre, was somewhat saddened by the thought.

All was quiet at the office on the following day. Bat Jarvis, again accompanied by the faithful Otto, took up his position in the inner room, prepared to repel all invaders; but none arrived. No sounds broke the peace of the outer office except the whistling of Master Maloney.

Things were almost dull when the telephone bell rang. Psmith took down the receiver.

“Hullo?” he said.

“I’m Parker,” said a moody voice.

Psmith uttered a cry of welcome.

“Why, Comrade Parker, this is splendid! How goes it? Did you get back all right yesterday? I was sorry to have to tear myself away, but I had other engagements. But why use the telephone? Why not come here in person? You know how welcome you are. Hire a taxi-cab and come right round.”

Mr. Parker made no reply to the invitation.

“Mr. Waring would like to see you.”

“Who, Comrade Parker?”

“Mr. Stewart Waring.”

“The celebrated tenement house-owner?”

Silence from the other end of the wire.

“Well,” said Psmith, “what step does he propose to take towards it?”

“He tells me to say that he will be in his office at twelve o’clock to-morrow morning. His office is in the Morton Building, Nassau Street.”

Psmith clicked his tongue regretfully.

“Then I do not see how we can meet,” he said. “I shall be here.”

“He wishes to see you at his office.”

“I am sorry, Comrade Parker. It is impossible. I am very busy just now, as you may know, preparing the next number, the one in which we publish the name of the owner of the Pleasant Street Tenements. Otherwise, I should be delighted. Perhaps later, when the rush of work has diminished somewhat.”

“Am I to tell Mr. Waring that you refuse?”

“If you are seeing him at any time and feel at a loss for something to say, perhaps you might mention it. Is there anything else I can do for you, Comrade Parker?”

“See here——”

“Nothing? Then good-bye. Look in when you’re this way.”

He hung up the receiver.

As he did so, he was aware of Master Maloney standing beside the table.

“Yes, Comrade Maloney?”

“Telegram,” said Pugsy. “For Mr. Windsor.”

Psmith ripped open the envelope.

The message ran:

“Returning to-day. Will be at office to-morrow morning,” and it was signed “Wilberfloss.”

“See who’s here!” said Psmith softly.

CHAPTER XXVIII.

standing room only.

N the light of subsequent events it was perhaps the least bit

unfortunate that Mr. Jarvis should have seen fit to bring with him to the office

of Cosy Moments on the following morning two of his celebrated squad of

cats, and that Long Otto, who, as usual, accompanied him, should have been fired

by his example to the extent of introducing a large and rather boisterous yellow

dog. They were not to be blamed, of course. They could not know that before the

morning was over space in the office would be at a premium. Still, it was

unfortunate.

N the light of subsequent events it was perhaps the least bit

unfortunate that Mr. Jarvis should have seen fit to bring with him to the office

of Cosy Moments on the following morning two of his celebrated squad of

cats, and that Long Otto, who, as usual, accompanied him, should have been fired

by his example to the extent of introducing a large and rather boisterous yellow

dog. They were not to be blamed, of course. They could not know that before the

morning was over space in the office would be at a premium. Still, it was

unfortunate.

Mr. Jarvis was slightly apologetic.

“T’ought I’d bring de kits along,” he said. “Dey started in scrappin’ yesterday when I was here, so to-day I says I’ll keep my eye on dem.”

Psmith inspected the menagerie without resentment.

“Assuredly, Comrade Jarvis,” he said. “They add a pleasantly cosy and domestic touch to the scene. The only possible criticism I can find to make has to do with their probable brawling with the dog.”

“Oh, dey won’t scrap wit de dawg. Dey knows him.”

“But is he aware of that? He looks to me a somewhat impulsive animal. Well, well, the matter’s in your hands. If you will undertake to look after the refereeing of any pogrom that may arise, I say no more.”

Mr. Jarvis’s statement as to the friendly relations between the animals proved to be correct. The dog made no attempt to annihilate the cats. After an inquisitive journey round the room he lay down and went to sleep, and an era of peace set in. The cats had settled themselves comfortably, one on each of Mr. Jarvis’s knees, and Long Otto, surveying the ceiling with his customary glassy stare, smoked a long cigar in silence. Bat breathed a tune, and scratched one of the cats under the ear. It was a soothing scene.

But it did not last. Ten minutes had barely elapsed when the yellow dog, sitting up with a start, uttered a whine. In the outer office could be heard a stir and movement. The next moment the door burst open and a little man dashed in. He had a peeled nose and showed other evidences of having been living in the open air. Behind him was a crowd of uncertain numbers. Psmith recognised the leaders of this crowd. They were the Reverend Edwin T. Philpotts and Mr. B. Henderson Asher.

“Why, Comrade Asher,” he said, “this is indeed a Moment of Mirth. I have been wondering for weeks where you could have got to. And Comrade Philpotts! Am I wrong in saying that this is the maddest, merriest day of all the glad New Year?”

The rest of the crowd had entered the room.

“Comrade Waterman, too!” cried Psmith. “Why, we have all met before. Except——”

He glanced inquiringly at the little man with the peeled nose.

“My name is Wilberfloss,” said the other with austerity. “Will you be so good as to tell me where Mr. Windsor is?”

A murmur of approval from his followers.

“In one moment,” said Psmith. “First, however, let me introduce two important members of our staff. On your right, Mr. Bat Jarvis. On your left, Mr. Long Otto. Both of Groome Street.”

The two Bowery boys rose awkwardly. The cats fell in an avalanche to the floor. Long Otto, in his haste, trod on the dog, which began barking, a process which it kept up almost without a pause during the rest of the interview.

“Mr. Wilberfloss,” said Psmith in an aside to Bat, “is widely known as a cat fancier in Brooklyn circles.”

“Honest?” said Mr. Jarvis. He tapped Mr. Wilberfloss in friendly fashion on the chest. “Say,” he asked, “did youse ever have a cat wit one blue and one yellow eye?”

Mr. Wilberfloss side-stepped and turned once more to Psmith, who was offering B. Henderson Asher a cigarette.

“Who are you?” he demanded.

“Who am I?” repeated Psmith in an astonished tone.

“Who are you?”

“I am Psmith,” said the old Etonian reverently. “There is a preliminary P before the name. This, however, is silent. Like the tomb. Compare such words as ptarmigan, psalm, and phthisis.”

“These gentlemen tell me you’re acting sub-editor. Who appointed you?”

Psmith reflected.

“It is rather a nice point,” he said. “It might be claimed that I appointed myself. You may say, however, that Comrade Windsor appointed me.”

“Ah! And where is Mr. Windsor?”

“In prison,” said Psmith sorrowfully.

“In prison!”

Psmith nodded.

“It is too true. Such is the generous impulsiveness of Comrade Windsor’s nature that he hit a policeman, was promptly gathered in, and is now serving a sentence of thirty days on Blackwell’s Island.”

Mr. Wilberfloss looked at Mr. Philpotts. Mr. Asher looked at Mr. Wilberfloss. Mr. Waterman started, and stumbled over a cat.

“I never heard of such a thing,” said Mr. Wilberfloss.

A faint, sad smile played across Psmith’s face.

“Do you remember, Comrade Waterman—I fancy it was to you that I made the remark—my commenting at our previous interview on the rashness of confusing the unusual with the improbable? Here we see Comrade Wilberfloss, big-brained though he is, falling into error.”

“I shall dismiss Mr. Windsor immediately,” said the big-brained one.

“From Blackwell’s Island?” said Psmith. “I am sure you will earn his gratitude if you do. They live on bean soup there. Bean soup and bread, and not much of either.”

He broke off, to turn his attention to Mr. Jarvis and Mr. Waterman, between whom bad blood seemed to have arisen. Mr. Jarvis, holding a cat in his arms, was glowering at Mr. Waterman, who had backed away and seemed nervous.

“What is the trouble, Comrade Jarvis?”

“Dat guy dere wit two left feet,” said Bat querulously, “goes and treads on de kit. I——”

“I assure you it was a pure accident. The animal——”

Mr. Wilberfloss, eyeing Bat and the silent Otto with disgust, intervened.

“Who are these persons, Mr. Smith?” he inquired.

“Poisson yourself,” rejoined Bat, justly incensed. “Who’s de little guy wit de peeled breezer, Mr. Smith?”

Psmith waved his hands.

“Gentlemen, gentlemen,” he said, “let us not descend to mere personalities. I thought I had introduced you. This, Comrade Jarvis, is Mr. Wilberfloss, the editor of this journal. These, Comrade Wilberfloss—Zam-buk would put your nose right in a day—are, respectively, Bat Jarvis and Long Otto, our acting fighting-editors, vice Kid Brady, absent on unavoidable business.”

“Kid Brady!” shrilled Mr. Wilberfloss. “I insist that you give me a full explanation of this matter. I go away by my doctor’s orders for ten weeks, leaving Mr. Windsor to conduct the paper on certain well-defined lines. I return yesterday, and, getting into communication with Mr. Philpotts, what do I find? Why, that in my absence the paper has been ruined.”

“Ruined?” said Psmith. “On the contrary. Examine the returns, and you will see that the circulation has gone up every week. Cosy Moments was never so prosperous and flourishing. Comrade Otto, do you think you could use your personal influence with that dog to induce it to suspend its barking for a while? It is musical, but renders conversation difficult.”

Long Otto raised a massive boot and aimed it at the animal, which, dodging with a yelp, cannoned against the second cat and had its nose scratched. Piercing shrieks cleft the air.

“I demand an explanation,” roared Mr. Wilberfloss above the din.

“I think, Comrade Otto,” said Psmith, “it would make things a little easier if you removed that dog.”

He opened the door. The dog shot out. They could hear it being ejected from the outer office by Master Maloney. When there was silence, Psmith turned courteously to the editor.

“You were saying, Comrade Wilberfloss——?”

“Who is this person Brady? With Mr. Philpotts I have been going carefully over the numbers which have been issued since my departure——”

“An intellectual treat,” murmured Psmith.

“—and in each there is a picture of this young man in a costume which I will not particularise——”

“There is hardly enough of it to particularise.”

“—together with a page of disgusting autobiographical matter.”

Psmith held up his hand.

“I protest,” he said. “We court criticism, but this is mere abuse. I appeal to these gentlemen to say whether this, for instance, is not bright and interesting.”

He picked up the current number of Cosy Moments, and turned to the Kid’s page.

“This,” he said. “Describing a certain ten-round unpleasantness with one Mexican Joe. ‘Joe comes up for the second round and he gives me a nasty look, but I thinks of my mother and swats him one in the lower ribs. He hollers foul, but nix on that. Referee says, “Fight on.” Joe gives me another nasty look. “All right, Kid,” he says; “now I’ll knock you up into the gallery.” And with that he cuts loose with a right swing, but I falls into the clinch, and then——!’”

“Bah!” exclaimed Mr. Wilberfloss.

“Go on, boss,” urged Mr. Jarvis approvingly. “It’s to de good, dat stuff.”

“There!” said Psmith triumphantly. “You heard? Comrade Jarvis, one of the most firmly established critics east of Fifth Avenue, stamps Kid Brady’s reminiscences with the hall-mark of his approval.”

“I falls fer de Kid every time,” assented Mr. Jarvis.

“Assuredly, Comrade Jarvis. You know a good thing when you see one. Why,” he went on warmly, “there is stuff in these reminiscences which would stir the blood of a jelly-fish. Let me quote you another passage to show that they are not only enthralling, but helpful as well. Let me see, where is it? Ah, I have it. ‘A bully good way of putting a guy out of business is this. You don’t want to use it in the ring, because by Queensberry Rules it’s a foul; but you will find it mighty useful if any thick-neck comes up to you in the street and tries to start anything. It’s this way. While he’s setting himself for a punch, just place the tips of the fingers of your left hand on the right side of his chest. Then bring down the heel of your left hand. There isn’t a guy living that could stand up against that. The fingers give you a leverage to beat the band. The guy doubles up, and you upper-cut him with your right, and out he goes.’ Now, I bet you never knew that before, Comrade Philpotts. Try it on your parishioners.”

“Cosy Moments,” said Mr. Wilberfloss irately, “is no medium for exploiting low prize-fighters.”

“Low prize-fighters! Comrade Wilberfloss, you have been misinformed. The Kid is as decent a little chap as you’d meet anywhere. You do not seem to appreciate the philanthropic motives of the paper in adopting Comrade Brady’s cause. Think of it, Comrade Wilberfloss. There was that unfortunate stripling with only two pleasures in life, to love his mother and to knock the heads off other youths whose weight coincided with his own; and misfortune, until we took him up, had barred him almost completely from the second pastime. Our editorial heart was melted. We adopted Comrade Brady. And look at him now! Matched against Eddie Wood! And Comrade Waterman will support me in my statement that a victory over Eddie Wood means that he gets a legitimate claim to meet Jimmy Garvin for the championship.”

“It is abominable,” burst forth Mr. Wilberfloss. “It is disgraceful. I never heard of such a thing. The paper is ruined.”

“You keep reverting to that statement, Comrade Wilberfloss. Can nothing reassure you? The returns are excellent. Prosperity beams on us like a sun. The proprietor is more than satisfied.”

“The proprietor?” gasped Mr. Wilberfloss. “Does he know how you have treated the paper?”

“He is cognisant of our every move.”

“And he approves?”

“He more than approves.”

Mr. Wilberfloss snorted.

“I don’t believe it,” he said.

The assembled ex-contributors backed up this statement with a united murmur. B. Henderson Asher snorted satirically.

“They don’t believe it,” sighed Psmith. “Nevertheless, it is true.”

“It is not true,” thundered Mr. Wilberfloss, hopping to avoid a perambulating cat. “Nothing will convince me of it. Mr. Benjamin White is not a maniac.”

“I trust not,” said Psmith. “I sincerely trust not. I have every reason to believe in his complete sanity. What makes you fancy that there is even a possibility of his being—er——?”

“Nobody but a lunatic would approve of seeing his paper ruined.”

“Again!” said Psmith. “I fear that the notion that this journal is ruined has become an obsession with you, Comrade Wilberfloss. Once again I assure you that it is more than prosperous.”

“If,” said Mr. Wilberfloss, “You imagine that I intend to take your word in this matter, you are mistaken. I shall cable Mr. White to-day, and inquire whether these alterations in the paper meet with his approval.”

“I shouldn’t, Comrade Wilberfloss. Cables are expensive, and in these hard times a penny saved is a penny earned. Why worry Comrade White? He is so far away, so out of touch with our New York literary life. I think it is practically a certainty that he has not the slightest inkling of any changes in the paper.”

Mr. Wilberfloss uttered a cry of triumph.

“I knew it,” he said, “I knew it. I knew you would give up when it came to the point, and you were driven into a corner. Now, perhaps, you will admit that Mr. White has given no sanction for the alterations in the paper?”

A puzzled look crept into Psmith’s face.

“I think, Comrade Wilberfloss,” he said, “we are talking at cross-purposes. You keep harping on Comrade White and his views and tastes. One would almost imagine that you fancied that Comrade White was the proprietor of this paper.”

Mr. Wilberfloss stared. B. Henderson Asher stared. Every one stared, except Mr. Jarvis, who, since the readings from the Kid’s reminiscences had ceased, had lost interest in the discussion, and was now entertaining the cats with a ball of paper tied to a string.

“Fancied that Mr. White . . . ?” repeated Mr. Wilberfloss. “I don’t follow you. Who is, if he isn’t?”

Psmith removed his monocle, polished it thoughtfully, and put it back in its place.

“I am,” he said.

CHAPTER XXIX.

the knock-out for mr. waring.

OU!” cried Mr. Wilberfloss.

OU!” cried Mr. Wilberfloss.

“The same,” said Psmith.

“You!” exclaimed Messrs. Waterman, Asher, and the Reverend Edwin Philpotts.

“On the spot!” said Psmith.

Mr. Wilberfloss groped for a chair and sat down.

“Am I going mad?” he demanded feebly.

“Not so, Comrade Wilberfloss,” said Psmith encouragingly. “All is well. The cry goes round New York, ‘Comrade Wilberfloss is to the good. He does not gibber.’ ”

“Do I understand you to say that you own this paper?”

“I do.”

“Since when?”

“Roughly speaking, about a month.”

Among his audience (still excepting Mr. Jarvis, who was tickling one of the cats and whistling a plaintive melody) there was a tendency toward awkward silence. To start bally-ragging a seeming nonentity and then to discover he is the proprietor of the paper to which you wish to contribute is like kicking an apparently empty hat and finding your rich uncle inside it. Mr. Wilberfloss in particular was disturbed. Editorships of the kind which he aspired to are not easy to get. If he were to be removed from Cosy Moments he would find it hard to place himself anywhere else. Editors, like manuscripts, are rejected from want of space.

“Very early in my connection with this journal,” said Psmith, “I saw that I was on to a good thing. I had long been convinced that about the nearest approach to the perfect job in this world, where good jobs are so hard to acquire, was to own a paper. All you had to do, once you had secured your paper, was to sit back and watch the other fellows work, and from time to time forward big cheques to the bank. Nothing could be more nicely attuned to the tastes of a Shropshire Psmith. The glimpses I was enabled to get of the workings of this little journal gave me the impression that Comrade White was not attached with any paternal fervour to Cosy Moments. He regarded it, I deduced, not so much as a life-work as in the light of an investment. I assumed that Comrade White had his price, and wrote to my father, who was visiting Carlsbad at the moment, to ascertain what that price might be. He cabled it to me. It was reasonable. Now it so happens that an uncle of mine some years ago left me a considerable number of simoleons, and though I shall not be legally entitled actually to close in on the opulence for a matter of nine months or so, I anticipated that my father would have no objection to staking me to the necessary amount on the security of my little bit of money. My father has spent some time of late hurling me at various professions, and we had agreed some time ago that the Law was to be my long suit. Paper-owning, however, may be combined with being Lord Chancellor, and I knew he would have no objection to my being a Napoleon of the Press on this side. So we closed with Comrade White, and——”

There was a knock at the door, and Master Maloney entered with a card.

“Guy’s waiting outside,” he said.

“ ‘Mr. Stewart Waring,’ ” read Psmith. “Comrade Maloney, do you know what Mahomet did when the mountain would not come to him?”

“Search me,” said the office-boy indifferently.

“He went to the mountain. It was a wise thing to do. As a general rule in life you can’t beat it. Remember that, Comrade Maloney.”

“Sure,” said Pugsy. “Shall I send the guy in?”

“Surest thing you know, Comrade Maloney.”

He turned to the assembled company.

“Gentlemen,” he said, “You know how I hate to have to send you away, but would you mind withdrawing in good order? A somewhat delicate and private interview is in the offing. Comrade Jarvis, we will meet anon. Your services to the paper have been greatly appreciated. If I might drop in some afternoon and inspect the remainder of your zoo——?”

“Any time you’re down Groome Street way. Glad.”

“I will make a point of it. Comrade Wilberfloss, would you mind remaining? As editor of this journal, you should be present. If the rest of you would look in about this time to-morrow— Show Mr. Waring in, Comrade Maloney.”

He took a seat.

“We are now, Comrade Wilberfloss,” he said, “at a crisis in the affairs of this journal, but I fancy we shall win through.”

The door opened, and Pugsy announced Mr. Waring.

The owner of the Pleasant Street Tenements was of what is usually called commanding presence. He was tall and broad, and more than a little stout. His face was clean-shaven and curiously expressionless. Bushy eyebrows topped a pair of cold grey eyes. He walked into the room with the air of one who is not wont to apologise for existing. There are some men who seem to fill any room in which they may be. Mr. Waring was one of these.

He set his hat down on the table without speaking. After which he looked at Mr. Wilberfloss, who shrank a little beneath his gaze.

Psmith had risen to greet him.

“Won’t you sit down?” he said.

“I prefer to stand.”

“Just as you wish. This is Liberty Hall.”

Mr. Waring again glanced at Mr. Wilberfloss.

“What I have to say is private,” he said.

“All is well,” said Psmith reassuringly. “It is no stranger that you see before you, no mere irresponsible lounger who has butted in by chance. That is Comrade J. Fillken Wilberfloss, the editor of this journal.”

“The editor? I understood——”

“I know what you would say. You have Comrade Windsor in your mind. He was merely acting as editor while the chief was away hunting sand-eels in the jungles of Texas. In his absence Comrade Windsor and I did our best to keep the old journal booming along, but it lacked the master-hand. But now all is well: Comrade Wilberfloss is once more doing stunts at the old stand. You may speak as freely before him as you would before well, let us say Comrade Parker.”

“Who are you, then, if this gentleman is the editor?”

“I am the proprietor.”

“I understood that a Mr. White was the proprietor.”

“Not so,” said Psmith. “There was a time when that was the case, but not now. Things move so swiftly in New York journalistic matters that a man may well be excused for not keeping abreast of the times, especially one who, like yourself, is interested in politics and house-ownership rather than in literature. Are you sure you won’t sit down?”

Mr. Waring brought his hand down with a bang on the table, causing Mr. Wilberfloss to leap a clear two inches from his chair.

“What are you doing it for?” he demanded explosively. “I tell you, you had better quit it. It isn’t healthy.”

Psmith shook his head.

“You are merely stating in other—and, if I may say so, inferior—words what Comrade Parker said to us. I did not object to giving up valuable time to listen to Comrade Parker. He is a fascinating conversationalist, and it was a privilege to hob-nob with him. But if you are merely intending to cover the ground covered by him, I fear I must remind you that this is one of our busy days. Have you no new light to fling upon the subject?”

Mr. Waring wiped his forehead. He was playing a lost game, and he was not the sort of man who plays lost games well. The Waring type is dangerous when it is winning, but it is apt to crumple up against strong defence.

His next words proved his demoralisation.

“I’ll sue you for libel,” said he.

Psmith looked at him admiringly.

“Say no more,” he said, “for you will never beat that. For pure richness and whimsical humour it stands alone. During the past seven weeks you have been endeavouring in your cheery fashion to blot the editorial staff of this paper off the face of the earth in a variety of ingenious and entertaining ways; and now you propose to sue us for libel! I wish Comrade Windsor could have heard you say that. It would have hit him right.”

Mr. Waring accepted the invitation he had refused before. He sat down.

“What are you going to do?” he said.

It was the white flag. The fight had gone out of him.

Psmith leaned back in his chair.

“I’ll tell you,” he said. “I’ve thought the whole thing out. The right plan would be to put the complete kybosh (if I may use the expression) on your chances of becoming an alderman. On the other hand, I have been studying the papers of late, and it seems to me that it doesn’t much matter who gets elected. Of course the opposition papers may have allowed their zeal to run away with them, but even assuming that to be the case, the other candidates appear to be a pretty fair contingent of blighters. If I were a native of New York, perhaps I might take a more fervid interest in the matter, but as I am merely passing through your beautiful little city, it doesn’t seem to me to make any very substantial difference who gets in. To be absolutely candid, my view of the thing is this. If the People are chumps enough to elect you, then they deserve you. I hope I don’t hurt your feelings in any way. I am merely stating my own individual opinion.”

Mr. Waring made no remark.

“The only thing that really interests me,” resumed Psmith, “is the matter of these tenements. I shall shortly be leaving this country to resume the strangle-hold on Learning which I relinquished at the beginning of the Long Vacation. If I were to depart without bringing off improvements down Pleasant Street way, I shouldn’t be able to enjoy my meals. The startled cry would go round Cambridge: ‘Something is the matter with Psmith. He is off his feed. He should try Blenkinsop’s Balm for the Bilious.’ But no balm would do me any good. I should simply droop and fade slowly away like a neglected lily. And you wouldn’t like that, Comrade Wilberfloss, would you?”

Mr. Wilberfloss, thus suddenly pulled into the conversation, again leaped in his seat.

“What I propose to do,” continued Psmith, without waiting for an answer, “is to touch you for the good round sum of five thousand and three dollars.”

Mr. Waring half rose.

“Five thousand dollars!”

“Five thousand and three dollars,” said Psmith. “It may possibly have escaped your memory, but a certain minion of yours, one J. Repetto, utterly ruined a practically new hat of mine. If you think that I can afford to come to New York and scatter hats about as if they were mere dross, you are making the culminating error of a misspent life. Three dollars are what I need for a new one. The balance of your cheque, the five thousand, I propose to apply to making those tenements fit for a tolerably fastidious pig to live in.”

“Five thousand!” cried Mr. Waring. “It’s monstrous.”

“It isn’t,” said Psmith. “It’s more or less of a minimum. I have made inquiries. So out with the good old cheque-book, and let’s all be jolly.”

“I have no cheque-book with me.”

“I have,” said Psmith, producing one from a drawer. “Cross out the name of my bank, substitute yours, and fate cannot touch us.”

Mr. Waring hesitated for a moment, then capitulated. Psmith watched, as he wrote, with an indulgent and fatherly eye.

“Finished?” he said. “Comrade Maloney.”

“Youse hollering fer me?” asked that youth, appearing at the door.

“Bet your life I am, Comrade Maloney. Have you ever seen an untamed mustang of the prairie?”

“Nope. But I’ve read about dem.”

“Well, run like one down to Wall Street with this cheque, and pay it in to my account at the International Bank.”

Pugsy disappeared.

“Cheques,” said Psmith, “have been known to be stopped. Who knows but what, on reflection, you might not have changed your mind?”

“What guarantee have I,” asked Mr. Waring, “that these attacks on me in your paper will stop?”

“If you like,” said Psmith, “I will write you a note to that effect. But it will not be necessary. I propose, with Comrade Wilberfloss’ assistance, to restore Cosy Moments to its old style. Some days ago the editor of Comrade Windsor’s late daily paper called up on the telephone and asked to speak to him. I explained the painful circumstances, and, later, went round and hob-nobbed with the great man. A very pleasant fellow. He asks to re-engage Comrade Windsor’s services at a pretty sizeable salary, so, as far as our prison expert is concerned, all may be said to be well. He has got where he wanted. Cosy Moments may therefore ease up a bit. If, at about the beginning of next month, you should hear a deafening squeal of joy ring through this city, it will be the infants of New York and their parents receiving the news that Cosy Moments stands where it did. May I count on your services, Comrade Wilberfloss? Excellent. I see I may. Then perhaps you would not mind passing the word round among Comrades Asher, Waterman, and the rest of the squad, and telling them to burnish their brains and be ready to wade in at a moment’s notice. I fear you will have a pretty tough job roping in the old subscribers again, but it can be done. I look to you, Comrade Wilberfloss. Are you on?”

Mr. Wilberfloss, wriggling in his chair, intimated that he was.

T was a drizzly November evening. The streets of Cambridge

were a compound of mud, mist, and melancholy. But in Psmith’s rooms the fire

burned brightly, the kettle droned, and all, as the proprietor had just

observed, was joy, jollity, and song. Psmith, in pyjamas and a college blazer,

was lying on the sofa. Mike, who had been playing football, was reclining in a

comatose state in an arm-chair by the fire.

T was a drizzly November evening. The streets of Cambridge

were a compound of mud, mist, and melancholy. But in Psmith’s rooms the fire

burned brightly, the kettle droned, and all, as the proprietor had just

observed, was joy, jollity, and song. Psmith, in pyjamas and a college blazer,

was lying on the sofa. Mike, who had been playing football, was reclining in a

comatose state in an arm-chair by the fire.

“How pleasant it would be,” said Psmith dreamily, “if all our friends on the other side of the Atlantic could share this very peaceful moment with us! Or perhaps not quite all. Let us say, Comrade Windsor in the chair over there, Comrades Brady and Maloney on the table, and our old pal Wilberfloss sharing the floor with B. Henderson Asher, Bat Jarvis, and the cats. By the way, I think it would be a graceful act if you were to write to Comrade Jarvis from time to time telling him how your Angoras are getting on. He regards you as the World’s Most Prominent Citizen. A line from you every now and then would sweeten the lad’s existence.”

Mike stirred sleepily in his chair.

“What?” he said drowsily.

“Never mind, Comrade Jackson. Let us pass lightly on. I am filled with a strange content to-night. I may be wrong, but it seems to me that all is singularly to de good, as Comrade Maloney would put it. Advices from Comrade Windsor inform me that that prince of blighters, Waring, was rejected by an intelligent electorate. Those keen, clear-sighted citizens refused to vote for him to an extent that you could notice without a microscope. Still, he has one consolation. He owns what, when the improvements are completed, will be the finest and most commodious tenement houses in New York. Millionaires will stop at them instead of going to the Plaza. Are you asleep, Comrade Jackson?”

“Um—m,” said Mike.

“That is excellent. You could not be better employed. Keep listening. Comrade Windsor also stated—as indeed did the sporting papers—that Comrade Brady put it all over friend Eddie Wood, administering the sleep-producer in the eighth round. My authorities are silent as to whether or not the lethal blow was a half-scissor hook, but I presume such to have been the case. The Kid is now definitely matched against Comrade Garvin for the championship, and the experts seem to think that he should win. He is a stout fellow, is Comrade Brady, and I hope he wins through. He will probably come to England later on. When he does, we must show him round. I don’t think you ever met him, did you, Comrade Jackson?”

“Ur-r,” said Mike.

“Say no more,” said Psmith. “I take you.”

He reached out for a cigarette.

“These,” he said, comfortably, “are the moments in life to which we look back with that wistful pleasure. What of my boyhood at Eton? Do I remember with the keenest joy the brain-tourneys in the old form-room, and the bally rot which used to take place on the Fourth of June? No. Burned deeply into my memory is a certain hot bath I took after one of the foulest cross-country runs that ever occurred outside Dante’s Inferno. So with the present moment. This peaceful scene, Comrade Jackson, will remain with me when I have forgotten that such a person as Comrade Repetto ever existed. These are the real Cosy Moments. And while on that subject you will be glad to hear that the little sheet is going strong. The man Wilberfloss is a marvel in his way. He appears to have gathered in the majority of the old subscribers again. Hopping mad but a brief while ago, they now eat out of his hand. You’ve really no notion what a feeling of quiet pride it gives you owning a paper. I try not to show it, but I seem to myself to be looking down on the world from some lofty peak. Yesterday night, when I was looking down from the peak without a cap and gown, a proctor slid up. To-day I had to dig down into my jeans for a matter of two plunks. But what of it? Life must inevitably be dotted with these minor tragedies. I do not repine. The whisper goes round, ‘Psmith bites the bullet, and wears a brave smile.’ Comrade Jackson——”

A snore came from the chair.

Psmith sighed. But he did not repine. He bit the bullet. His eyes closed.

Five minutes later a slight snore came from the sofa, too. The man behind Cosy Moments slept.

Madame Eulalie’s Rare Plums

Madame Eulalie’s Rare Plums