Chapter 11

The Great Food Question

JIMMY was helpless. He realised that. He was as certain as he had ever been of anything that he had seen Mr. Spinder place the blue stone in his pocket; but he knew that he had no means of proving it. Mr. Spinder could bring Herr Steingruber to witness that the stone had been lost on the golf-links. Jimmy saw that, at any rate, for the time, he was beaten. He left the room without another word.

The mystery of the thing began to bewilder him more and more. What was this blue stone that Mr. Spinder should deliberately steal it, and then lie to hide the fact that he had stolen it? The stone had evidently a value which the ordinary person did not recognise. Witness the attitude of Tommy Armstrong and Herr Steingruber towards it. Why should Mr. Spinder of all people recognise this value? Jimmy worried over these problems till he went to bed, and far into the night.

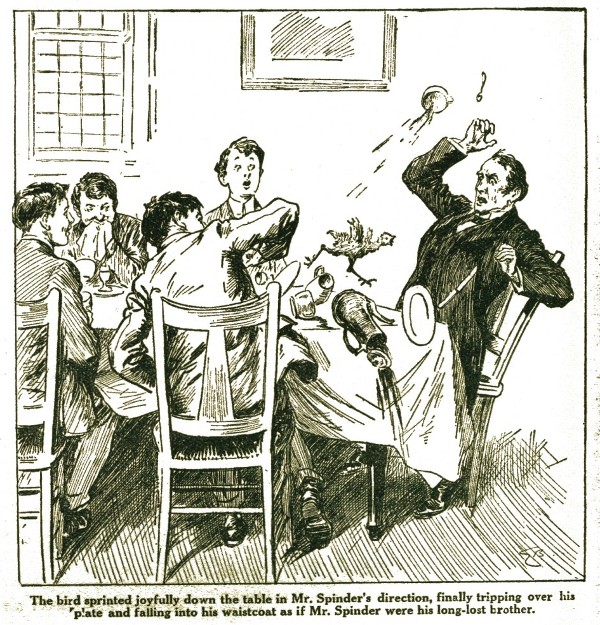

Next day there were distractions. During breakfast Tommy Armstrong, by way of drawing attention to the inferior state of the food supplied to the house, had taken the step of letting loose a live chicken, which he had bought for the purpose on the previous afternoon, and preserved during the night in a cardboard box with holes bored in the lid. The bird, surprised and relieved to find itself once more at liberty, had sprinted joyfully down the table in Mr. Spinder’s direction, finally tripping over his plate, and falling on to his waistcoat as if Mr. Spinder were his long-lost brother. Mr. Spinder rose, white with rage. “Who brought that bird into the room?” he cried.

There was a moment’s silence. After which Tommy said that he thought it must have come out of one of the eggs. A raucous laugh, in unison, from the Teeth brothers, had brought Mr. Spinder’s wrath to the boiling-point. He stammered in his fury. Just as it seemed that he might proceed to attack Tommy, and engage him in a hand to hand struggle, his attention was diverted by the chicken, which, after lying on the floor for a while in an apparently fainting condition, now revived, and made a dash for the door. Everybody rose from his place, and charged after it, with the exception of Bellamy, who continued to pound away steadily at bread-and-butter. In the confusion Mr. Spinder forgot Tommy; and when things were comparatively quiet again, he informed the whole house that it would write him out the first ten pages of the Latin grammar. He then swept out of the room, followed by the chicken, which had once more got loose. The first skirmish, it was felt, had ended rather in his favour. The general opinion of the house was that further steps would have to be taken. The thing was discussed in the common-room after school.

“It’s no good doing things on a small scale like this,” said Tommy. “He’s bound to score. He just sets us imposts, and there we are. What we want is to organise. We must have a regular strike. For goodness’ sake, somebody, kill those two farmyard-imitators.”

This remark was caused by the thoughtless behaviour of Binns and Sloper, who, not finding the debate greatly to their interest, had begun to sing an extract from the music-hall songs of the day. Sloper had just requested some person unknown to put him amongst the girls, to which Binns had added explanatorily, anxious apparently that there should be no mistake, “those with the curly curls,” when the meeting descended upon the warblers in the usual manner, and the duet came to an end in a cloud of dust.

“Forge ahead, Tommy,” said Catford, from his seat on Binns’s chest. “You were saying something about striking.”

“Yes. I’ve got an idea. Suppose we all absolutely refused to touch the food. He couldn’t do anything then. There’s no rule forcing one to eat. We would be quite quiet and respectful about it, only we would simply not touch the stuff. He’d have to do something then. What do you think about it?”

It seemed that the meeting thought a good deal about it, one way and another. A perfect babel of sound arose, everybody giving his opinion as loud as he was able. The plump form of Ram was seen placidly climbing on to his favourite table. Ram was the popular orator, and his appearance was nearly always the signal for silence.

“Hon’ble Armstrong,” said Ram, “must forgive me if I meet his suggestion with a nolo episcopari and miss-in-baulk. For why, misters? Hon’ble Armstrong has asked us to abstain from food and to let no mutton, no beef, no fowl egg pass the locked door of our firmly-clenched teeth. But, lackaday, this is surely as if to milk the ram. For how without food, even if that food be the unappetising and a bit off, shall we support life and not pop off mortal coil, as Hon’ble Shakespeare says? ’Tis better, misters, as Hon’ble Shakespeare also says, to bear with the ship-snaps we know of than fly to others which may prove but a jumping from frying-pan into fire. Half a loaf is better than an entire nullity of the staff of life. Hoity-toity, without food we shall has if to swoon away on class-room floor.”

These eminently sound opinions were greeted with applause. Tommy, however, did not seem to think much of them.

“You silly goat,” he said, complainingly, “I never meant that we should do the fasting man act. If you thought more and jawed less, Ram, you’d get on better.”

“What is the idea?” asked Browning.

“Why, simply to lay in a stock of grub on our own. Chaps in the army often do it. If they get fed up with the grub that’s served out to them, they just sit tight and wait till afterwards, when they have a chance of buying what they want. See the idea? Let’s lay in supplies, and then we can begin to get moving.”

“It’s not a bad idea,” said Morrison. “But where’s the money to come from?”

“Rem acu tetigisti,” said Ram. “You have touched the spot, Hon’ble Morrison. Where are we to find the sinews of war?”

“We’d better have a whip round,” said Tommy. “I’ll lead off with a quid. My uncle gave me one when I went to see him.”

The magnificence of this offer impressed the meeting. Here was something practical. Now he was talking. Unfortunately, the other donations fell a good deal short of this lofty standard. The Teeth happened to have had a postal order for five shillings by that morning’s post from an indulgent grandmother; and Catford disgorged half a crown, but the sum total of the collection only panned out at two pounds. A penny less, to be exact.

“The question is,” said Tommy, having counted the money, “how long can we keep going on two quid? There are thirty of us here. That only works out at a bit over a bob each. You can’t go on long on a bob and twopence, or whatever it is.”

A blank gloom settled on the meeting. Two pounds had seemed an enormous sum up till then, but, looked at in that way, as having to be divided up amongst thirty boys, there did not appear to be so much of it as one thought.

Tommy was the first to recover from the shock.

“I tell you what it is,” he said. “We must raise some more. For the strike to be worth anything we must be ready to go on with it for nearly a week. It’s no good doing it for one day. He’d simply think we’d got the pip or something. Everyone had better write home for money. If that fails, we shall have to try something else.”

A muffled voice spoke from the floor. It was recognised as that of Sloper.

“If one or two of you men of wrath would kindly get off my chest,” said the voice, “I should like to make a suggestion. Don’t mind me, though: I don’t want to spoil your simple pleasures.”

“Let him up,” said Tommy. “But if you only want to break into one of your beastly songs again, you’ll jolly well be knocked down and jumped on by the whole strength of the company.”

“You wrong me,” said Sloper. “You pain me deeply. All I wanted was to do you a good turn. It’s like this. Why not give a concert in aid of the strike fund, and charge sixpence or a bob for admission? Binns and I,” added the speaker, modestly, “wouldn’t mind giving you the benefit of our trained skill. We’ll sing as many songs as you like.”

“I bet you will,” said Tommy. “It’s not a bad idea, though, I must say. The fellows would roll up like anything, especially if we told them what it was for.”

“We could hold it in the gym,” suggested Binns. “Sloper and I would do a duet we heard in the pantomime last year. It goes like this.”

But the audience were on the watch, and headed him off.

“Chuck it,” said Tommy. “Plenty of time for that. No need to hear your beastly voice before the night. What do you chaps say to this concert idea?”

Everybody seemed in favour of it. There was more talent in Spinder’s house common-room, it appeared, than the casual observer would have imagined. The place simply reeked with it. Ram offered to recite Shakespeare. The only difficulty with Binns and Sloper was to prevent them monopolising the entire bill. Catford thought he could remember some conjuring tricks, if given time. The Teeth volunteered to box a few rounds. And nearly everybody else had something to offer.

“Good,” said Tommy. “It’s going to be a strong programme. Hullo, Morrison, what are you going to do? Play any instrument? Or is a song more in your line?”

“I don’t know what you’re jawing about,” said Morrison, who had just entered. “Is Jimmy Stewart anywhere about? Oh, there you are, Jimmy. I say, I met a man out in the road who says he wants to see you. Wouldn’t tell me what it was about. So I said I’d nip in and fetch you. He looks like an old soldier. Says his name’s Burrows. Got one arm in a sling.”

“Where is he?” asked Jimmy, dismally. Sam Burrows was the last man in the world he wanted to see just then.

Chapter 12

A Visit from Burrows

A DIM figure loomed up in the darkness as Jimmy went out into the road.

“That you, matey?” said a voice.

“Hullo,” said Jimmy.

The figure drew a deep breath, and came a step nearer. It was Sam Burrows, sure enough. Jimmy saw that, as Morrison had said, his arm was in a sling. His first question concerned itself with Sam’s wound.

“How’s your shoulder?” he asked. “Surely it can’t be all right again yet?”

“Rightly speaking, sir, it isn’t. I expect the doctor is sayin’ things about me at this very moment. ‘Don’t you dream of stirring for a week,’ he says. ‘Right, sir,’ says I. But, love us, I couldn’t keep lying on my back, wondering all the while if that brawsted blackie with the twisted leg had got hold of the stone, and if you’d been shot at same as me. I couldn’t do it, matey. Thinking of it over, as I lay there, I says to myself, ‘Sam, you’ve been and played that young gentleman a dirty trick. What d’you mean by shifting all the responserbility off of your own shoulders on to his?’ And I says, ‘You just go off quietly, without saying a word to the doctor, and get that stone back from him, and see the thing through off yer own. It ain’t fair to a nipper to put such a thing on to him.’ So last night I slips out of the house, treks quietly to the station, and waits for the first train. And here I am, so now let’s have that bit of blue ruin back, matey, and you can go and sleep quietly in your little bed, which I lay you haven’t done up to now. Let’s have it, matey.”

Jimmy did not attempt to break the thing gently.

“I can’t,” he said, miserably. “It’s gone.”

Sam stood stock still for a second before speaking.

“Gawd!” he said at last. “What!”

“It’s gone.”

“Gone! ’Ow? They ain’t bin and got it? Not that blackie and his gang?”

“No, it’s not him. It’s not been stolen at all, really.”

“You ain’t lost it?”

Jimmy explained. Sam listened attentively. When Jimmy had come to the end of his story, he whistled.

“It’s a rum start,” he said. “This ’ere what’s-his-name now——”

“Spinder.”

“This ’ere Spinder. What’s his game?”

“I can’t make out. That’s what’s puzzling me. I’m as certain as anything that I saw him take the stone off the table and shove it into his pocket. I know he was lying when he said he hadn’t. I couldn’t do anything, of course. But he’s got it, I know.”

“What sort of a man might he be?”

“I don’t know. He’s a new master. He only came this term. Nobody seems to like him much. But I don’t know why he should take the stone.”

“But he has?”

“I’m absolutely certain of it.”

“And you ain’t seen anything of the blackie and his lot?”

“Not since I got here. But—I didn’t tell you at the time——”

“What’s that, matey?”

Jimmy related briefly all that had taken place on the night of Sam’s injury, and the day after—the face at the window, the burglar, the man in the train, and the unfortunate request of Tommy Armstrong to be shown the blue stone. Sam sucked in his breath. He was plainly deeply interested.

“This ’ere chum of yours, Tommy What’s-’is-name, seems to be one of the cloth-heads, he does. Pity he ain’t got more sense in him.”

“He’s rather mucked things up, hasn’t he? But, of course, he didn’t realise how awfully important the stone was.”

“He’s put the lid on it, he has,” said Sam. “’E’s brought the whole gang of them on your track, and now he’s let this ’ere Spinder get ’old of the stone. The only thing to be done now is to try and get it back from Spinder. That’s what we must do.”

“But how?”

“Ah, that’s it. How? Where does he live, now?”

“That’s his window over there on the ground floor.”

“On the ground floor,” repeated Sam thoughtfully. “That window with the red blind, I take it?”

“That’s the one.”

“I see. Well, the only thing now is to sit and think things over a bit. Let’s only ’ope as how it’s only this Mr. Spinder of yours as we have to tackle. That blooming blackie may make things worse by coming down on us at any moment. He’s watching and waiting his time, you may depend on it, if he’s this side of the water at all. Maybe he’s still in India. Which’ll be a mercy for us if he is. Good-bye, matey, for the present. Keep your mouth shut about having seen me.”

Sam disappeared into the darkness. Jimmy went back to the common-room again, where he found the strikers still busily engaged in discussing the proposed concert. Ram was still on the table, but no one was listening to him. The Teeth seemed to be rehearsing for the boxing exhibition which they had promised to give. Binns and Sloper were warbling unchecked. Tommy, crimson in the face, was endeavouring to obtain a hearing on the next table to Ram’s. Jimmy surveyed the scene, and went out again. It was no good trying to get Tommy to himself now. If he wanted to talk things over with him he must wait till later. It may seem surprising that, after the way in which Tommy had allowed the stone to become lost, he should wish to consult him at all. But Jimmy, though he had not much opinion of Tommy’s discretion, had a solid respect for his ingenuity. And it struck him that the present was an occasion where ingenuity and daring were required. There was the stone securely held by Mr. Spinder. How it was to be recovered Jimmy did not know. That was where Tommy would come in. The problem was one which ought just to suit him.

It was not till they were in their room that night that he found an opportunity of tackling him on the subject. And even then he could not approach it at once, for Tommy was too full of the concert to listen.

“It’s going to be the biggest thing ever done at Marleigh,” he said, as he began to undress. “I’d no idea the place was so chock-full of talent. To look at Pilbury, for instance, you wouldn’t think he was a very brainy chap, would you? Nothing out of the common, I mean. My dear chap, that fellow can imitate a pig being killed till you’d almost swear it was the real thing. Catford, too——”

“I say, Tommy.”

“Catford can do things with a top-hat which would surprise you. And, of course, Binns and Sloper are ready to go on murdering comic songs till we go on to the stage and drag them off. By the way, what are you going to do?”

“I don’t know. Look here, Tommy.”

“Don’t know? What rot. You must think of something. I know. You’ve been to India, haven’t you?”

“Yes.”

“Well, you shall give a ten minutes lecture on India, accompanied by magic lantern-slides. I’ve got a set of slides. They’re Egypt, really, but no one’ll know the difference. That’ll be top hole. I’ll put your name down on the programme as a lightning lecturer. You’ll knock ’em.”

“I say, Tommy——”

“What’s up now?”

“Chuck all this concert rot for a second. I’m in an awful mess. That stone——”

“Oh, lord, you’re not worrying about that still, are you? I’ll get it from old Steingruber to-morrow first thing. What a chap you are for pegging away at one idea. Old Steingruber’ll give it up like a shot. I’ll ask him to play his ’cello. By gad!” Tommy leaped excitedly on his bed. “I’ve got the idea of the century. I’ll get him to play the ’cello as a turn at the concert. It’ll——”

“But he hasn’t got it. Do listen for a second. This is frightfully important.”

“Hasn’t got it? What’s he done with it? Popped it?”

“He lost it on the links.”

“Well, it wasn’t much of a thing, after all. I always said so. Now it’s really gone for good you can drop all this mysterious assassin rot, and turn your mind to the serious things of life, such as this concert. If only old Steingruber will play the ’cello——”

“But you haven’t heard everything. He was playing with Spinder when he lost it.”

“Rum tastes some men have. Fancy choosing Spinder to play with.”

“And now Spinder’s got it.”

“But you said it was lost.”

“That’s the queer part of it. Spinder must have picked it up and pocketed it. I went into his room to show up some lines, and there he was, gloating over it. When he saw me, he snatched it up, shoved it in his pocket, and absolutely denied that he had got it. I knew he had, and he knew I knew, but all the same he simply swore he hadn’t. So I had to go away. What I want to know is, how shall I get it back? I must somehow. I’m dashed if I see how, though.”

Tommy felt pleased. He looked at Jimmy approvingly. This was playing the game of make-believe as it should be played. So many people would have chucked the whole thing on finding that the German master had lost the stone on the links. But Jimmy, he reflected, always had been a queer, imaginative sort of fellow, always reading books, and that sort of thing. Tommy still clung to his belief that the whole affair was nothing more than an elaborate game of Jimmy’s. Not so much a practical joke exactly as a means of manufacturing artificial excitement. The winter term was dull as a rule, and Jimmy was evidently determined that this one should be an exception. It was a curious sort of game, but it certainly had possibilities in the way of excitement; and that was all that Tommy required.

“I’ll tell you what you must do,” he said gravely.

“What’s that?”

“Search Spinder’s room,” said Tommy with tremendous earnestness. “Search it through and through. He’s certain to have the stone hidden somewhere in it. This is going to be a regular Sherlock Holmes business. You’ve come to the right man. I’ll see you through. We’ll do it to-night.”

Jimmy’s heart leaped. It was risky, of course, but this was no time for counting risks.

“But why should you come and risk getting caught?” he said.

Tommy dismissed the objection with a wave of the hand.

“My dear sir,” he said, “this business is now in my hands. I’m in charge of it.”

(Next week’s instalment tells of a most exciting incident. Don’t forget !)

Madame Eulalie’s Rare Plums

Madame Eulalie’s Rare Plums