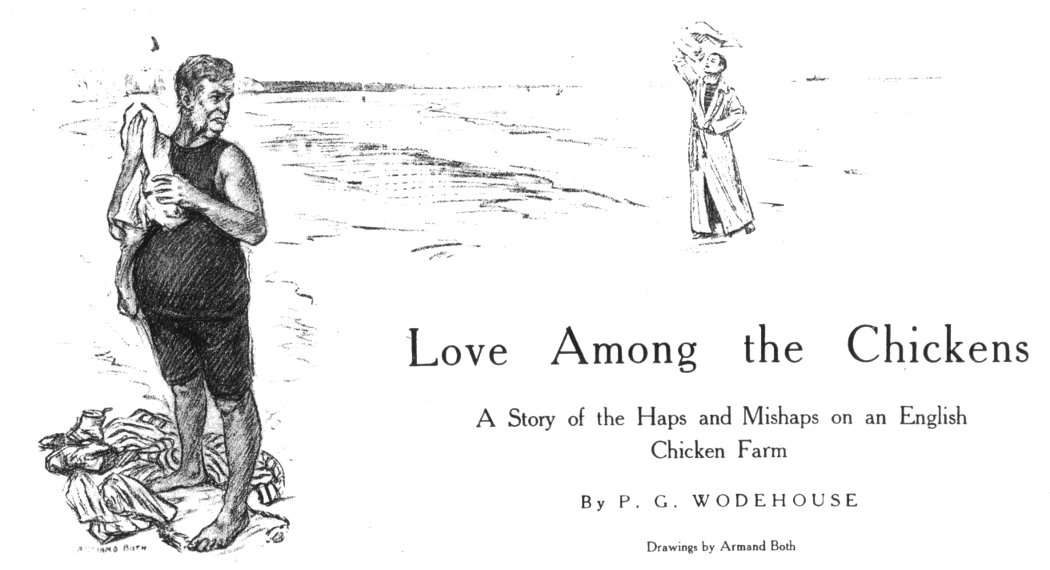

The Circle, January 1909

Chapter XIII

A Council of War

HE

fact is,” said Ukridge, “if things go on as they are now, old horse, we shall be in the

cart. This business wants bucking up. We don’t seem to be making headway. What

we want is time. If only these scoundrels of tradesmen would leave us alone

for a spell, we might get things going properly.”

HE

fact is,” said Ukridge, “if things go on as they are now, old horse, we shall be in the

cart. This business wants bucking up. We don’t seem to be making headway. What

we want is time. If only these scoundrels of tradesmen would leave us alone

for a spell, we might get things going properly.”

“You don’t let me see the financial side of the thing,” I said, “except at intervals. Why don’t you keep me thoroughly posted? I didn’t know we were in such a bad way. As far as I can see, we’re going strong. Chicken for breakfast, lunch, and dinner is a shade monotonous; but look at the business we’re doing. We sold a whole heap of eggs last week.”

“It’s not enough, Garny, my boy. We sell a dozen eggs where we ought to be selling a hundred, carting them off in trucks for the London market. Harrod’s and Whiteley’s and the rest of them are beginning to get on their hind legs and talk. That’s what they’re doing. You see, Marmaduke, there’s no denying it—we did touch them for a lot of things on account, and they agreed to take it out in eggs. They seem to be getting tired of waiting. They said that to send thirteen eggs as payment for goods supplied to the value of £25 1s 6d was mere trifling. Trifling!—when those thirteen eggs were absolutely all we had over that week after Mrs. Beale had taken what she wanted for the kitchen. I tell you what it is, old boy, that woman literally eats eggs.”

“The habit is not confined to her,” I said.

“What I mean to say is, she seems to bathe in them.”

An impressive picture to one who knew Mrs. Beale.

“She says she needs so many for puddings, dear,” said Mrs. Ukridge. “I spoke to her about it yesterday. And, of course, we often have omelets.”

“She can’t make omelets without breaking eggs,” I urged.

“She can’t make them without breaking us,” said Ukridge. “One or two more omelets, and we’re done for. Another thing,” he continued, “that rotten incubator won’t work. I don’t know what’s wrong with it!”

“Perhaps it’s your dodge of letting down the temperature.”

I had touched upon a tender point.

“My dear fellow,” he said, earnestly, “there’s nothing the matter with my figures. It’s a mathematical certainty. What’s the good of mathematics if not to help you work out that sort of thing? No, there’s something wrong with the machine itself. Where did we get the incubator, Millie?”

“Harrod’s, I think, dear. Yes, it was Harrod’s. It came down with the first lot of things from there.”

“Then,” said Ukridge, banging the table with his fist, while his glasses flashed triumph, “we’ve got ’em. Write and answer that letter of theirs to-night, Millie. Sit on them.”

“Yes, dear.”

“And tell ’em that we’d have sent ’em their confounded eggs, weeks ago, if only their rotten, twopenny-ha’penny incubator had worked with any approach to decency.”

“Or words to that effect,” I suggested.

“Add in a postscript that I consider that the manufacturer of the thing ought to rent a padded cell at EarlswoodThe Royal Earlswood Asylum for Idiots at Redhill, Surrey, and that they are scoundrels for palming off a groggy machine of that sort on me. I’ll teach them!”

“Yes, dear.”

“The ceremony of opening the morning’s letters at Harrod’s ought to be full of interest and excitement to-morrow,” I said.

This dashing counterstroke served to relieve Ukridge’s pessimistic mood. He seldom looked on the dark side of things for long at a time. He began now to speak hopefully of the future. He planned out ingenious, if somewhat impracticable, improvements in the farm. Our fowls were to multiply so rapidly and consistently that within a short space of time Dorsetshire would be paved with them. Our eggs were to increase in size till they broke records and got three-line notices in the “Items of Interest” column of the Daily Mail. Briefly, each hen was to become a happy combination of rabbit and ostrich.

“There is certainly a good time coming,” I said. “May it be soon. Meanwhile, there remain the local tradesmen. What of them?”

Ukridge relapsed once more into pessimism.

“They are the worst of the lot,” he said. “I don’t mind about the London men so much. They only write; and a letter or two hurts nobody. But when it comes to butchers and bakers and grocers and fishmongers and fruiterers and what not coming up to one’s house and dunning one in one’s garden—well, it’s a little hard—what?”

It may be wondered why, before things came to such a crisis, I had not placed my balance at the bank at the disposal of the senior partner for use on behalf of the firm. The fact was that my balance was at the moment small. I have not yet in the course of this narrative gone into my pecuniary position, but I may state here that it was an inconvenient one. My parents had been poor, but I had a wealthy uncle. He was a great believer in matrimony, as, having married three wives—not, I should add, simultaneously—he had every right to be. He was also of opinion that the less money the young bachelor possessed, the better. The consequence was that he announced his intention of giving me a handsome allowance from the day that I married, but not an instant before. Till that glad day I would have to shift for myself. And I am bound to admit that—for an uncle—it was a remarkably sensible idea. I am also of opinion that it is greatly to my credit, and proof of my pure and unmercenary nature, that I did not instantly put myself up to be raffled forAs did Reginald Bunthorne in Gilbert & Sullivan’s Patience, or rush out into the streets and propose marriage to the first lady I met. But I was making enough with my pen to support myself, and, be it ever so humble, there is something pleasant in a bachelor existence, or so I had thought until very recently.

Having exhausted the subject of finance—or, rather, when I began to feel that it was exhausting me—I took my clubs and strolled up the hill to the links, to play off a match with a sportsman from the village. I had entered some days previously a competition for a trophy (I quote the printed notice) presented by a local supporter of the game, in which up to the present I was getting on nicely. I had just got into the semifinals. Unless I had bad luck, I felt that I ought to get into the final and win it. As far as I could gather from watching the play of my rivals, the professor was the best of them, and I was convinced that I should have no difficulty with him. But he had the most extraordinary luck at golf, and he also exercised quite an uncanny influence on his opponent. I have seen men put completely off their stroke by his good fortune.

In the club house I met the professor, who had just routed his opponent, and so won through to the semifinal. He was warm, but jubilant.

I congratulated him, and left the place.

Phyllis was waiting outside. She often went round the course with him.

“Good afternoon,” I said. “Have you been round with the professor?”

“Yes. You and father will both be in the semifinals, won’t you? I hope you will play very badly.”

“Thank you, Miss Derrick,” I said.

“Yes, it does sound rude, doesn’t it? But father has set his heart on winning, this year. Do you know that he has played in the final round two years running now?”

“Really?”

“Both times he was beaten by the same man.”

“Who was that? Mr. Derrick plays a much better game than anybody I have seen on these links.”

“It was nobody who is here now. It was a Colonel Jervis. He has not come to Lyme Regis this year. That is why father is hopeful.”

“Logically,” I said, “he ought to be certain to win.”

“Yes, but, you see, you were not playing last year, Mr. Garnet.”

“Oh, it’s more than likely that I shall fail miserably if I ever do play your father in the final. There are days when I play golf very badly.”

“Then I hope it will be on one of those days that you play father.”

“I hope so, too,” I said.

“You hope so?”

“Yes.”

“But don’t you want to win?”

“I should prefer to please you.”

Mr. Lewis WallerEnglish actor/manager (1860–1915), known for romantic leads in a variety of plays from Shakespeare to Wilde, with a dedicated audience of female admirers could not have said it better.

“Really, how very unselfish of you, Mr. Garnet,” she replied, with a laugh. “I had no idea that such chivalry existed. I thought a golfer would sacrifice anything to win a game.”

“Most things.”

“And trample on the feelings of anybody.”

“Not everybody,” I said.

At this point the professor joined us.

Chapter XIV

The Arrival of Nemesis

I AWOKE three days after my meeting with the professor at the club house filled with a dull foreboding. Somehow I seemed to know that that day was going to turn out badly for me. It may have been liver or a chill, but it was certainly not the weather. The morning was perfect, the most glorious of a glorious summer. There was a haze over the valley and out to sea which suggested a warm noon, when the sun should have begun the serious duties of the day.

Bob was in his favorite place on the gravel. I took him with me down to the Cob to watch me bathe.

“What’s the matter with me to-day, Robert, old man?” I asked him, as I dried myself.

He blinked lazily, but contributed no suggestion.

“It’s no good looking bored,” I went on, “because I’m going to talk about myself, however much it bores you. Here am I, as fit as a prize fighter; living in the open air for I don’t know how long, eating good, plain food, bathing every morning—sea bathing, mind you—and yet what’s the result? I feel beastly.”

Bob yawned, and gave a little whine.

“Yes,” I said, “I know I’m in love. But that can’t be it, because I was in love just as much a week ago, and I felt all right then. But isn’t she an angel, Bob? Eh? Isn’t she? But how about Tom Chase? Don’t you think he’s a dangerous man? He calls her by her Christian name, you know, and behaves generally as if she belonged to him. And then he sees her every day, while I have to trust to meeting her at odd times, and then I generally can’t think of anything to talk about except golf and the weather. He probably sings duets with her after dinner—and you know what comes of duets after dinner.”

Here Bob, who had been trying for some time to find a decent excuse for getting away, pretended to see something of importance at the other end of the Cob, and trotted off to investigate it.

“Of course,” I said to myself, “it may be merely hunger. I may be all right after breakfast, but at present I seem to be working up for a really fine fit of the blues.”

I whistled for Bob, and started for home. On the beach I saw the professor some little distance away and waved my towel in a friendly manner. He made no reply.

Of course, it was possible that he had not seen me, but for some reason his attitude struck me as ominous. As far as I could see he was looking straight at me and he was not a short-sighted man. I could think of no reason why he should cut me. We had met on the links on the previous morning, and he had been friendliness itself. He had called me “me dear boy,” supplied me with ginger beer at the club house, and generally behaved as if he had been David and I Jonathan“And it came to pass . . . that the soul of Jonathan was knit with the soul of David, and Jonathan loved him as his own soul.” 1 Samuel 18:1 [IM]. Yet in certain moods we are inclined to make mountains out of molehills, and I went on my way puzzled and uneasy, with a distinct impression that I had certainly received the cut direct.

Breakfast was ready when I got in. There was a cold chicken on the sideboard, devilled chicken on the table, and a trio of boiled eggs, and a dish of scrambled eggs. I helped myself to the latter.

Ukridge was sorting the letters when I sat down.

“Morning, Garny,” he said. “One for you, Millie.”

“It’s from Aunt Elizabeth,” said Mrs. Ukridge, looking at the envelope.

“Wish she’d enclose a cheque. She could spare it.”

“I think she would, dear, if she knew how much it was needed. But I don’t like to ask her. She’s so curious and says such horrid things.”

“She does,” said Ukridge, gloomily. He probably spoke from experience. “Two for you, Sebastian. All the rest for me. Eighteen of them, and all bills. Those chicken men, the dealer people, you know, want me to pay up for the first lot of hens. Considering that they all died of roop, and that I was going to send them back anyhow after I’d got them to hatch out a few chickens, I call that cool. I can’t afford to pay heavy sums for birds which die off quicker than I can get them in. It isn’t business.”

It was not my business, at any rate, so I switched off my attention from Ukridge’s troubles and was opening the first of my two letters when an exclamation from Mrs. Ukridge made me look up.

She had dropped the letter she had been reading and was staring indignantly in front of her. There were two little red spots on her cheeks.

“I shall never speak to Aunt Elizabeth again,” she said.

“What’s the matter, old chap?” inquired Ukridge, affectionately, glancing up from his pile of bills. “Aunt Elizabeth been getting on your nerves again? What’s she been saying this time?”

Mrs. Ukridge left the room with a sob.

Ukridge sprang at the letter.

“If that demon doesn’t stop writing letters and upsetting Millie I shall lynch her,” he said. I had never seen him so genuinely angry. He turned over the pages till he came to the passage which had caused the trouble. “Listen to this, Garnet. ‘I am sorry, but not surprised, to hear that the chicken farm is not proving a great success. I think you know my opinion of your husband. He is perfectly helpless in any matter requiring the exercise of a little common sense and business capability.’ I like that! ’Pon my soul, I like that! You’ve known me longer than she has, Garny, and you know that it’s just in matters requiring common sense that I come out strong—what?”

“Of course, old man,” I replied, dutifully. “The woman must be a fool.”

“That’s what she calls me two lines further on. No wonder Millie was upset. Why can’t these cats leave people alone? Look here! On the next page she calls me a gabya simpleton, in northern and midlands British dialect!”

“It’s time you took a strong hand.”

“And in the very next sentence refers to me as a perfect guffina stupid, clumsy person. What’s a guffin, Garny, old boy?”

“It sounds indecent.”

“I believe it’s actionablegrounds for a lawsuit.”

“I shouldn’t wonder.”

Ukridge rushed to the door.

“Millie!” he shouted.

No answer.

He slammed the door, and I heard him dashing upstairs.

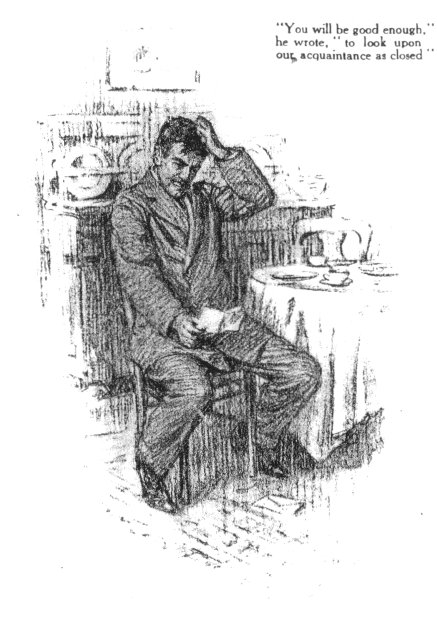

I turned with a sense of relief to my letters. One was from Lickford. The other was in a strange handwriting. I looked at the signature. Patrick Derrick. This was queer. What had the professor to say to me?

The next moment my heart seemed to spring to my throat.

“Sir,” the letter began.

A pleasant, cheery beginning!

Then it got off the mark, so to speak, like lightning. There was no sparring for an opening, no dignified parade of set phrases leading up to the main point. It was the letter of a man who was almost too furious to write.

“You will be good enough,” he wrote, “to look on our

acquaintance as closed. I have no wish

to associate with persons of your stamp. If we should happen to meet, you will

be good enough to treat me as a total stranger, as I shall treat you. And, if I

may be allowed to give you a word of advice, I

should recommend you in future, when you wish to exercise your humor, to

do so in some less practical manner than by bribing boatmen to upset your—(friends

crossed out thickly, and

acquaintances substituted). If you

require further enlightenment in this matter, the enclosed letter may be of service

to you.”

“You will be good enough,” he wrote, “to look on our

acquaintance as closed. I have no wish

to associate with persons of your stamp. If we should happen to meet, you will

be good enough to treat me as a total stranger, as I shall treat you. And, if I

may be allowed to give you a word of advice, I

should recommend you in future, when you wish to exercise your humor, to

do so in some less practical manner than by bribing boatmen to upset your—(friends

crossed out thickly, and

acquaintances substituted). If you

require further enlightenment in this matter, the enclosed letter may be of service

to you.”

With which he remained mine faithfully, Patrick Derrick.

The enclosed letter was from one Jane Muspratt. It was bright and interesting:

Dear Sir:

My

Harry, Mr. Hawk, sas to me how it was

him upseting the boat and you, not because he is not steddy in a boat

which he is—no man more so in Lyme Regis—but because one of

the gentmen what keeps chikkens up the hill, the little one, Mr. Garnick

his name is, says to him Hawk, I’ll give you a sovrin to upset

Mr. Derrick in your boat, and my Harry being esily led was took in and did,

but he’s sory now and wishes he hadn’t, and he sas he’ll

niver do a prackticle joke again for anyone even for a bank note.

Yours obedly,

Jane Muspratt.

Oh, woman! woman!

At the bottom of everything! History is full of tragedies caused by the lethal sex.

Who lost Mark Antony the world? A woman.from Thomas Otway’s play The Orphan (1680); often quoted by Wodehouse’s misogynistic characters, including Tom Garth in the Kid Brady stories, Eustace Hignett in The Girl on the Boat, and Kipper Herring in How Right You Are, Jeeves. Who let Samson in so atrociously? Woman again. Why did Bill Bailey leave home? Once more, because of a woman. And here was I, Jerry Garnet, harmless, well-meaning writer of minor novels, going through the same old mill.

I cursed Jane Muspratt. What chance had I with Phyllis now? Could I hope to win over the professor again? I cursed Jane Muspratt for the second time.

My thoughts wandered to Mr. Harry Hawk. The villain! The scoundrel! What business had he to betray me? . . . The Demon!

My life—ruined. My future—gray and blank. My heart—shattered. And why? Because of the scoundrel, Hawk.

Phyllis would meet me in the village, on the Cob, on the links, and pass by as if I were the Invisible ManH. G. Wells’s novella of this title appeared in 1897.. And why? Because of the reptile, Hawk. The worm, Hawk. The varlet, Hawk.

I crammed my hat on and hurried out of the house toward the village.

Chapter XV

A Chance Meeting

I ROAMED the place in search of the varlet for the space of half an hour, and, after having drawn all his familiar haunts, found him at length leaning over the sea wall near the church, gazing thoughtfully into the waters below.

I confronted him.

“Well,” I said, “you’re a beauty, aren’t you?”

He eyed me owlishly. Even at this early hour, I was grieved to see he showed signs of having looked on the bitter while it was brownWodehouse’s original variation on “Look not thou upon the wine when it is red” (Proverbs 23:31).

“Beauty?” he echoed.

“What have you got to say for yourself?”

It was plain that he was engaged in pulling his faculties together by some laborious process known only to himself. At present my words conveyed no meaning to him. He was trying to identify me. He had seen me before somewhere, he was certain, but he could not say where, or who I was.

“I want to know,” I said, “what induced you to be such an abject idiot as to let our arrangement get known.”

He continued to stare at me. Then a sudden flash of intelligence lit up his features.

“Mr. Garnick,” he said.

“You’ve got it at last.”

He stretched out a huge hand.

“I want to know,” I said, distinctly, “what you’ve got to say for yourself after letting our affair with the professor become public property?”

He paused awhile in thought.

“Dear sir,” he said, at last, as if he were dictating a letter, “dear sir, I owe you—ex—exp——”

He waved his hand, as who should say, “It’s a stiff job, but I’m going to do it.”

“Explashion,” he said.

“You do,” said I, grimly. “I should like to hear it.”

“Dear sir, listen me.”

“Go on, then.”

“You came me. You said, ‘Hawk, Hawk, ol’ fren’, listen me. You tip this ol’ bufflehead into sea,’ you said, ‘an’ gormed if I don’t give ’ee a gould savrin.’ That’s what you said me. Isn’t that what you said me?”

I did not deny it.

“Ve’ well. I said you, ‘Right,’ I said. I tipped the ol’ soul into sea, and I got the gould savrin.”

“Yes, you took care of that. All this is quite true, but it’s beside the point. We are not disputing about what happened. What I want to know for the third time—is what made you let the cat out of the bag. Why couldn’t you keep quiet about it?”

He waved his hand.

“Dear sir,” he replied, “this way. Listen me.”

It was a tragic story that he unfolded. My wrath ebbed as I listened. After all, the fellow was not so greatly to blame. I felt that in his place I should have acted as he had done. Fate was culpable, and Fate alone.

It appeared that he had not come well out of the matter of the accident. I had not looked at it hitherto from his point of view. While the rescue had left me the Popular Hero, it had had quite the opposite result for him. He had upset his boat, and would have drowned his passenger, said Public Opinion, if the young hero from London—myself—had not plunged in and at the risk of his life brought the professor to shore. Consequently, he was despised by all as an inefficient boatman. He became a laughing stock. The local wags made laborious jests when he passed.

Now, all this Mr. Hawk, it seemed, would have borne cheerfully and patiently for my sake, or, at any rate, for the sake of the good golden sovereign I had given him. But a fresh factor appeared in the problem, complicating it grievously. To wit, Miss Jane Muspratt.

“She said me,” explained Mr. Hawk, with pathos, “ ‘Harry ’Awk,’ she said, ‘yeou’m a girt fuledialect variation of ‘great fool’, an’ I don’t marry noone as is ain’t to be trusted in a boat by hisself, and what has jokes made about him by that Tom Leigh.’ I punched Tom Leigh,” observed Mr. Hawk, parenthetically. “ ‘So,’ she said me, ‘yeou can go away, an’ I don’t want to see yeou again.’ ”

This heartless conduct on the part of Miss Muspratt had had the natural result of making him confess all in self-defense; and she had written to the professor the same night.

I forgave Mr. Hawk. I think he was hardly sober enough to understand, for he betrayed no emotion.

“It is Fate, Hawk,” I said, “simply Fate. There is a divinity that shapes our ends, rough-hew them how we willHamlet, V, ii, and it’s no good grumbling.”

“Yiss,” said Mr. Hawk, after chewing this sentiment for a while in silence, “so she said me, ‘Hawk,’ she said—like that—‘you’re a girt fule’——”

“That’s all right,” I replied. “I quite understand. As I say, it’s simply Fate. Good-by.”

And I left him.

As I was going back, I met the professor and Phyllis. They passed me without a look.

I wandered on in quite a fervor of self-pity. I was in one of those moods when life suddenly seems to become irksome, when the future stretches blank and gray in front of one. In such a mood it is imperative that one should seek distraction. The shining example of Mr. Harry Hawk did not lure me. Taking to drink would be a nuisance. Work was what I wanted. I would toil like a navvyoriginally, a worker employed in digging navigational canals; hence, any strenuous manual laborer all day among the fowls, separating them when they fought, gathering in the eggs when they laid, chasing them across country when they got away, and even, if necessity arose, painting their throats with turpentine when they were stricken with roop. Then after dinner I would steal away to my bedroom, and write—and write—and write; and go on writing till my fingers were numb and my eyes refused to do their duty. And when time had passed I might come to feel that it was all for the best. A man must go through the fire before he can write his masterpiece. We learn in suffering what we teach in songsaid of poets by Percy Bysshe Shelley, in “Julian and Maddalo” (1819).

Thus might I some day feel that all this anguish was really a blessing—effectively disguised.

But I doubted it.

We were none of us very cheerful now at the farm. Even Ukridge’s spirit was a little daunted by the bills which poured in by every post. It was as if the tradesmen of the neighborhood had formed a league and were working in concert. Or it may have been due to thought waves. We lived in a continual atmosphere of worry. Chicken and nothing but chicken at meals, and chicken and nothing but chicken between meals had frayed our nerves. An air of defeat hung over the place. We were a beaten side and we realized it. We had been playing an uphill game for nearly two months and the strain was beginning to tell. And as for me, I have never since spent so profoundly miserable a week. I was not even permitted the anodyne of work. There seemed to be nothing to do on the farm. The chickens were quite happy and only asked to be let alone and allowed to have their meals at regular intervals. And every day one or more of their number would vanish into the kitchen and Mrs. Beale would serve up the corpse in some cunning disguise and we would try to delude ourselves into the idea that it was something altogether different.

There was one solitary gleam of variety in our menu. An editor sent me a cheque for a guinea for a set of verses. We cashed that cheque and trooped round the town in a body, laying out the money. We bought a leg of mutton, and a tongue, and sardines, and pineapple chunks, and potted meat, and many other noble things and had a perfect banquet.

After that we relapsed into routine again.

Deprived of physical labor, with the exception of golf and bathing—trivial sports compared with work in the fowl runs at its hardest—I tried to make up for it by working at my novel. It refused to materialize.

It was on one of the many occasions on which I had sat in my room, pen in hand, through the whole of a lovely afternoon, with no better result than a slight headache, that I bethought me of a little paradise I had once discovered on the Ware Cliff, an enchanting spot, hung over the sea and backed by green woods. I had not been there for some time, owing principally to an entirely erroneous idea that I could do more solid work sitting in a straight, hard chair at a table than lying on soft turf with the sea wind in my eyes.

But now the desire to visit that little clearing again

drove me from my room. The Ware Cliff was the best medicine for me. What does

Kipling say?From Just So Stories, “The Camel’s Hump”:

And then you will find that the sun and the wind,

And the Djinn of the Garden too,

Have lifted the hump—

The horrible hump—

The hump that is black and blue!

‘Hump’ was then a slang term for a spell of depression or grouchiness; ‘Cameelions’ in this Circle Magazine edition and in the 1909 book edition is a misprint for ‘cameelious’—an invented adjective that appears in other stanzas of Kipling’s poem, and that is correctly spelled in the 1906 original edition and the 1921 revision of this book.

And soon you will find that the sun and the wind

And the Djinn of the Garden, too,

Have lightened the Hump, Cameelions Hump,

The Hump that is black and blue.

His instructions include digging with a hoe and a shovel also, but I could omit that. The sun and wind were what I needed.

I took the upper road.

In certain moods I preferred it to the path along the cliff. To reach my favorite clearing I had to take to the fields on the left and strike down hill in the direction of the sea. I hurried down the narrow path.

I broke into the clearing at a jog trot and stood panting. And at the same moment, looking cool and beautiful in her white dress, Phyllis entered it from the other side. Phyllis—without the professor.

Chapter XVI

Of a Sentimental Nature

SHE was wearing a Panama, and she carried

a sketching-blockpad of artist’s paper, sometimes contained in a firm cover and camp stool.

and camp stool.

“Good evening,” I said.

“Good evening,” said she.

It is curious how different the same words can sound when spoken by different people. My “good evening” might have been that of a man with a particularly guilty conscience caught in the act of doing something more than usually ignoble. She spoke like a somewhat offended angel.

“It’s a lovely evening,” I went on, pluckily.

“Very.”

“The sunset!”

“Yes.”

“Er——”

She raised a pair of blue eyes, devoid of all expression save a faint suggestion of surprise, gazed through me for a moment at some object a couple of thousand miles away, and lowered them again, leaving me with a vague feeling that there was something wrong with my personal appearance.

Very calmly she moved to the edge of the cliff, arranged her camp stool and sat down. Neither of us spoke a word. I watched her while she filled a little mug with water from a little bottle, opened her paint box, selected a brush, and placed her sketching-block in position.

She began to paint.

Now, by all the laws of good taste I should before this have made a dignified exit. It was plain that I was not regarded as an essential ornament of this portion of Ware Cliff. By now, I ought to have been a quarter of a mile away.

But there is a definite limit to what a man can do. I remained.

The sinking sun flung a carpet of gold across the sea. Phyllis’ hair was tinged with it. Little waves tumbled lazily on the beach below. Except for the song of a distant blackbird, running through its repertory before retiring for the night, everything was silent, especially Phyllis.

She sat there, dipping and painting and dipping again, with never a word for me—standing patiently and humbly behind her.

“Miss Derrick,” I said.

She half turned her head.

“Yes?”

“Why won’t you speak to me?” I said.

“I don’t understand you.”

“Why won’t you speak to me?”

“I think you know, Mr. Garnet.”

“It is because of that boat accident?”

“Accident!”

“Episode,” I emended.

She went on painting in silence. From where I stood I could see her profile. Her chin was tilted. Her expression was determined.

“But,” I added, “I should have liked a chance to defend myself. . . . What glorious sunsets there have been these last few days. I believe we shall have this sort of weather for another month.”

“I should not have thought that possible.”

“The glass is going up,” I said.

“I was not talking about the weather.”

“It was dull of me to introduce such a wornout topic.”

“You said you could defend yourself.”

“I said I should like the chance to do so.”

“Then you shall have it.”

“That is very kind of you. Thank you.”

“Is there any reason for gratitude?”

“Every reason.”

“Go on, Mr. Garnet. I can listen while I paint. But please sit down. I don’t like being talked to from a height.”

I sat down on the grass in front of her, feeling as I did so that the change of position in a manner clipped my wings. It is difficult to speak movingly while sitting on the ground. Instinctively I avoided eloquence. Standing up, I might have been pathetic and pleading. Sitting down, I was compelled to be matter-of-fact.

“You remember, of course, the night you and Professor Derrick dined with us? When I say dined, I use the word in a loose sense.”

For a moment I thought she was going to smile. We were both thinking of Edwin. But it was only for a moment, and then her face grew cold once more, and the chin resumed its angle of determination.

“Yes?” she said.

“You remember the unfortunate ending of the festivities?”

“Well?”

“I naturally wished to mend matters. It occurred to me that an excellent way would be by doing your father a service. It was seeing him fishing that put the idea of a boat accident into my head. I hoped for a genuine boat accident; but those things only happen when one does not want them. So I determined to engineer one.”

“You didn’t think of the shock to my father.”

“I did. It worried me very much.”

“But you upset him, all the same.”

“Reluctantly.”

She looked up and our eyes met. I could detect no trace of forgiveness in hers.

“You behaved abominably,” she said.

“I played a risky game and I lost, and I shall now take the consequences. With luck I should have won. I did not have luck, and I am not going to grumble about it. But I am grateful to you for letting me explain. I should not have liked you to go on thinking that I played practical jokes on my friends. That is all I have to say, I think. It was kind of you to listen. Good-by, Miss Derrick.”

I got up.

“Are you going?”

“Why not?”

“Please sit down again.”

“But you wish to be alone——”

“Please sit down!”

There was a flush on the cheek turned toward

me and the chin was tilted higher.

There was a flush on the cheek turned toward

me and the chin was tilted higher.

I sat down.

To westward the sky had changed to the hue of a bruised cherry. The sun had sunk below the horizon and the sea looked cold and leaden. The blackbird had long since gone to bed.

“I am glad you told me, Mr. Garnet.”

She dipped her brush in the water.

“Because I don’t like to think badly of—people.”

She bent her head over her painting.

“Though I still think you behaved very wrongly. And I am afraid my father will never forgive you for what you did.”

Her father! As if he counted!

“But you do?” I said, eagerly.

“I think you are less to blame than I thought you were at first.”

“No more than that?”

“You can’t expect to escape all consequences. You did a very stupid thing.”

“Consider the temptation.”

The sky was a dull gray now. It was growing dusk. The grass on which I sat was wet with dew.

I stood up.

“Isn’t it getting a little dark for painting?” I said. “Are you sure you won’t catch cold? It’s very damp.”

“Perhaps it is. And it is late, too.”

She shut her paint box and emptied the little mug on the grass.

“You will let me carry your things?” I said.

I think she hesitated, but only for a moment. I possessed myself of the camp-stool, and we started on our homeward journey. We both were silent. The spell of the quiet summer evening was on us.

“ ‘And all the air a solemn stillness holds,’from Thomas Gray’s “Elegy Written in a Country Churchyard,” line 6 (1751) ” she said, softly. “I love this cliff, Mr. Garnet. It’s the most soothing place in the world.”

“I have found it so this evening.”

She glanced at me quickly.

“You’re not looking well,” she said. “Are you sure you are not overworking yourself?”

“No, it’s not that.”

Somehow we had stopped as if by agreement and were facing each other. There was a look in her eyes I had never seen there before. The twilight hung like a curtain between us and the world. We were alone together in a world of our own.

“It is because I had displeased you,” I said.

She laughed nervously.

“I have loved you ever since I first saw you,” I said doggedly.

(To be continued)

Editor’s notes:

Earlswood: The Royal Earlswood Asylum for Idiots at Redhill, Surrey

put myself up to be raffled for: as did Reginald Bunthorne in Gilbert & Sullivan’s Patience

Mr. Lewis Waller: English actor/manager (1860–1915), known for romantic leads in a variety of plays from Shakespeare to Wilde, with a dedicated audience of female admirers

he David and I Jonathan: “And it came to pass . . . that the soul of Jonathan was knit with the soul of David, and Jonathan loved him as his own soul.” 1 Samuel 18:1 [IM]

gaby: a simpleton, in northern and midlands British dialect

guffin: a stupid, clumsy person

actionable: grounds for a lawsuit

Who lost Mark Antony the world? A woman: from Thomas Otway’s play The Orphan (1680); often quoted by Wodehouse’s misogynistic characters, including Tom Garth in the Kid Brady stories, Eustace Hignett in The Girl on the Boat, and Kipper Herring in How Right You Are, Jeeves.

the Invisible Man: H. G. Wells’s novella of this title appeared in 1897.

looked on the bitter while it was brown: Wodehouse’s original variation on “Look not thou upon the wine when it is red” (Proverbs 23:31)

girt fule: dialect variation of ‘great fool’

There is a divinity that shapes our ends, rough-hew them how we will: Hamlet, V, ii

navvy: originally, a worker employed in digging navigational canals; hence, any strenuous manual laborer

learn in suffering what we teach in song: said of poets by Percy Bysshe Shelley, in “Julian and Maddalo” (1819)

What does Kipling say?: From Just So Stories: “The Camel’s Hump”

And then you will find that the sun and the wind,

And the Djinn of the Garden too,

Have lifted the hump—

The horrible hump—

The hump that is black and blue!

‘Hump’ was then a slang term for a spell of depression or grouchiness; ‘Cameelions’ in this Circle Magazine edition and in the 1909 book edition is a misprint for ‘cameelious’—an invented adjective that appears in other stanzas of Kipling’s poem, and that is correctly spelled in the 1906 original edition and the 1921 revision of Love Among the Chickens.

sketching-block: pad of artist’s paper, sometimes contained in a firm cover

‘And all the air

a solemn stillness holds’: from Thomas Gray’s “Elegy Written in a Country Churchyard,” line 6 (1751)

—Notes by Neil Midkiff, with contributions from Ian Michaud

Madame Eulalie’s Rare Plums

Madame Eulalie’s Rare Plums