Liberty, July 9, 1927

THANKS to the publicity given to the matter in the Bridgnorth, Shifnal, and Albrighton Argus (with which is incorporated the Wheat-Growers’ Intelligencer and Stock-Breeders’ Gazetteer), the whole world to-day knows that the silver medal in the fat pigs’ class at the Eighty-seventh Annual Shropshire Agricultural Show was won by the Earl of Emsworth’s black Berkshire sow, Empress of Blandings.

Very few people, however, are aware how near that splendid animal came to missing the coveted honor.

Now it can be told.

This brief chapter of secret history may be said to have begun on the night of the 18th of July, when George Cyril Wellbeloved, pig man in the employ of Lord Emsworth, was arrested by Police Constable Evans of Market Blandings for being drunk and disorderly in the tap-room of the Goat and Feathers. On July 19, after first offering to apologize, then explaining that it had been his birthday, and finally attempting to prove an alibi, George Cyril was very properly jugged for fourteen days without the option of a fine.

On July 20, Empress of Blandings, always hitherto a hearty and even a boisterous feeder, for the first time on record declined all nourishment. And on the morning of July 21, the veterinary surgeon, called in to diagnose and deal with this strange asceticism, was compelled to confess to Lord Emsworth that the thing was beyond his professional skill.

The effect of the veterinary surgeon’s announcement on Lord Emsworth was overwhelming. As a rule, the wear and tear of our complex modern life left this vague and amiable peer unscathed. So long as he had sunshine, regular meals, and complete freedom from the society of his young son Frederick, he was placidly happy.

But there were chinks in his armor, and one of these had been pierced this morning. Dazed by the news he had received, he stood at the window of the great library of Blandings Castle, looking out with unseeing eyes.

As he stood there, the door opened. Lord Emsworth turned and, having blinked once or twice, as was his habit when confronted suddenly with anything, recognized in the handsome and imperious-looking woman who had entered, his sister, Lady Constance Keeble. Her demeanor, like his own, betrayed the deepest agitation.

“Clarence,” she cried, “an awful thing has happened!”

Lord Emsworth nodded dully.

“I know. He’s just told me.”

“What! Has he been here?”

“Only this moment left.”

“Why did you let him go? You must have known I would want to see him.”

“What good would that have done?”

“I could at least have assured him of my sympathy,” said Lady Constance stiffly.

“Yes, I suppose you could,” said Lord Emsworth, having considered the point. “Not that he deserves any sympathy. The man’s an ass.”

“Nothing of the kind. A most intelligent young man, as young men go.”

“Young? Would you call him young? Fifty, I should have said, if a day.”

“Are you out of your senses? Heacham fifty?”

“Not Heacham; Smithers.”

As frequently happened when in conversation with her brother, Lady Constance experienced a swimming sensation in the head.

“Will you kindly tell me, Clarence, in a few simple words, what you imagine we are talking about?”

“I’m talking about Smithers. Empress of Blandings is refusing her food, and Smithers says he can’t do anything about it. And he calls himself a vet!”

“Then you haven’t heard. Clarence, a dreadful thing has happened. Angela has broken off her engagement to Heacham.”

“And the agricultural show on Wednesday week!”

“What on earth has that got to do with it?” demanded Lady Constance, feeling a recurrence of the swimming sensation.

“What has it got to do with it?” said Lord Emsworth warmly. “My champion sow, with less than ten days to prepare herself for a most searching examination in competition with all the finest pigs in the county, starts refusing her food—”

“WILL you stop maundering on about your insufferable pig and give your attention to something that really matters? I tell you that Angela—your niece Angela—has broken off her engagement to Lord Heacham and expresses her intention of marrying that hopeless ne’er-do-well, James Belford!”

“The son of old Belford, the parson?”

“Yes.”

There was a silence. Brother and sister remained for a space plunged in thought. Lord Emsworth was the first to speak.

“We’ve tried acorns,” he said. “We’ve tried skim milk. And we’ve tried potato peel. But no, she won’t touch them.”

Conscious of two eyes raising blisters on his sensitive skin, he came to himself with a start.

“Absurd! Ridiculous! Preposterous!” he said hurriedly. “Breaking the engagement? Pooh! Tush! What nonsense! I’ll have a word with that young man. If he thinks he can go about the place playing fast and loose with my niece and jilting her without so much as a—”

“Clarence!”

Lord Emsworth blinked. It seemed to him that in his last speech he had struck just the right note—strong, forceful, dignified.

“Eh?” he muttered, brought to earth again.

“It is Angela who has broken the engagement.”

“Oh, Angela?”

“She is infatuated with this man Belford. And the point is, what are we to do about it?”

Lord Emsworth reflected.

“Take a strong line,” he said firmly. “Stand no nonsense. Don’t send ’em a wedding present.”

There is no doubt that, given time, Lady Constance would have found and uttered some adequately corrosive comment on this imbecile suggestion; but even as she was swelling preparatory to giving tongue, the door opened and a girl came in.

She was a pretty girl, with fair hair and blue eyes that, in their softer moments, probably reminded all sorts of people of twin lagoons slumbering beneath a southern sky.

This, however, was not one of those moments. To Lord Emsworth, as they met his, they looked like something out of an oxyacetylene blowpipe. Angela, it seemed to him, was upset about something; and he was sorry. He liked Angela.

To ease a tense situation, he said:

“Angela, my dear, do you know anything about pigs?”

The girl laughed—one of those sharp, bitter laughs that are so unpleasant just after breakfast.

“Yes, I do. You’re one.”

“Me?”

“Yes, you. Aunt Constance says that if I marry Jimmy you won’t let me have my money.”

“Money? Money?” Lord Emsworth was mildly puzzled. “What money? You never lent me any money.”

Lady Constance’s feelings found vent in a sound like an overheated radiator.

“I believe this absent-mindedness of yours is nothing but a ridiculous pose, Clarence. You know perfectly well that when poor Julia died she made you Angela’s trustee.”

“And I can’t touch my money without your consent till I’m twenty-five.”

“Well, how old are you?”

“Twenty-one.”

“THEN what are you worrying about?” asked Lord Emsworth, surprised. “No need to worry about it for another four years. God bless my soul, the money is quite safe. It is in excellent securities.”

Angela stamped her foot. An unladylike action, no doubt, but much better than kicking an uncle with it, as her lower nature prompted.

“I have told Angela,” explained Lady Constance, “that, while we naturally cannot force her to marry Lord Heacham, we can at least keep her money from being squandered by this wastrel on whom she proposes to throw herself away.”

“He isn’t a wastrel. He’s got quite enough money to marry me on, but he wants some capital to buy a partnership in a—”

“He is a wastrel. Wasn’t he sent abroad because—”

“That was two years ago. And since then—”

“My dear Angela, you may argue until—”

“I’m not arguing. I’m simply saying that I’m going to marry Jimmy if we have to starve in the gutter.”

“What gutter?” asked his lordship, wrenching his errant mind away from thoughts of acorns.

“Any gutter.”

“Now, please listen to me, Angela—”

Lord Emsworth had the sensation of having become a mere bit of flotsam upon a tossing sea of female voices. He looked wistfully at the door—

IT was smoothly done. A twist of the handle and he was galloping gayly down the stairs. He charged into the sunshine.

His gayety was not long-lived. Each step that took him nearer to the sty where the ailing Empress resided seemed a heavier step than the last. He reached the sty and, draping himself over the rails, peered moodily at the vast expanse of pig within.

For, even though she had been doing a bit of dieting of late, Empress of Blandings was far from being an ill-nourished animal. She resembled a captive balloon with ears and a tail, and was as nearly circular as a pig can be without bursting.

Nevertheless, Lord Emsworth, as he regarded her, mourned and would not be comforted. A few more square meals under her belt, and no pig in all Shropshire could have held its head up in the Empress’ presence. And now, just for lack of those few meals, the supreme animal would probably be relegated to the mean obscurity of an “honorably mentioned.”

He became aware that somebody was speaking to him and, turning, perceived a solemn young man in riding breeches.

“I say,” said the young man.

Lord Emsworth, though he would have preferred solitude, was relieved to find that the intruder was at least one of his own sex.

“I say, I’ve just ridden over to see if there was anything I could do about this fearful business.”

“Uncommonly kind and thoughtful of you, my dear fellow,” said Lord Emsworth, touched. “I fear things look very black.”

“It’s an absolute mystery to me.”

“To me, too.”

“I mean to say, she was all right last week.”

“She was all right as late as the day before yesterday.”

“And then this happens—out of a blue sky, as you might say.”

“Exactly. It is insoluble. We have done everything possible to tempt her appetite.”

“Her appetite? Why—is Angela ill?”

“Angela? No, I fancy not. She seemed perfectly well a few minutes ago.”

“You’ve seen her this morning, then? Did she say anything about this fearful business?”

“No. She was speaking about some money.”

“It’s all so dashed unexpected.”

“Like a bolt from the blue,” agreed Lord Emsworth. “Such a thing has never happened before. I fear the worst. According to the Wolff-Lehmann Feeding Standards, a pig, if in health, should consume daily nourishment amounting to fifty-seven thousand eight hundred calories, these to consist of proteids four pounds five ounces, carbohydrates twenty-five pounds—”

“What has that got to do with Angela?”

“Angela?”

“I came to find out why Angela has broken off our engagement.”

Lord Emsworth marshaled his thoughts.

“Ah, yes, of course. She has broken off the engagement, hasn’t she? I believe it is because she is in love with someone else. Yes, now that I recollect, that was distinctly stated. Angela has decided to marry someone else. I knew there was some satisfactory explanation. Tell me, my dear fellow, what are your views on linseed meal?”

“What do you mean, linseed meal?”

“Why, linseed meal,” said Lord Emsworth, not being able to find a better definition, “as a food for pigs.”

“Oh, curse all pigs!”

Lord Emsworth watched him, as he strode away, with an emotion that was partly indignation and partly relief—indignation that a landowner and a fellow son of Shropshire could have brought himself to utter such words, and relief that one capable of such utterance was not going to marry into his family.

HE had always in his woolen-headed way been very fond of his niece Angela, and it was nice to think that the child had such solid good sense and so much cool discernment. Many girls of her age would have been carried away by the glamour of young Heacham’s position and wealth; but she, divining with an intuition beyond her years that he was unsound on the subject of pigs, had drawn back while there was still time and refused to marry him.

A pleasant glow suffused Lord Emsworth’s bosom, to be frozen out a few minutes later as he perceived his sister Constance bearing down upon him. Lady Constance was a beautiful woman, but there were times when the charm of her face was marred by a rather curious expression; and from nursery days onward his lordship had been aware that this expression meant trouble. She was wearing it now.

“Clarence,” she said. “I have had enough of this nonsense of Angela and young Belford. The thing cannot be allowed to go drifting on. You must catch the two-o’clock train to London.”

“What! Why?”

“You must see this man Belford and tell him that, if Angela insists on marrying him, she will not have a penny for four years. I shall be greatly surprised if that piece of information does not put an end to the whole business.”

Lord Emsworth scratched meditatively at the Empress’ tanklike back. A mutinous expression was on his mild face.

“Don’t see why she shouldn’t marry the fellow,” he mumbled.

“Marry James Belford?”—exasperatedly.

“I don’t see why not. Seems fond of him and all that.”

“You never have had a grain of sense in your head, Clarence. Angela is going to marry Heacham.”

“Can’t stand that man. All wrong about pigs.”

“Clarence, I don’t wish to have any more discussion and argument. You will go to London on the two-o’clock train. You will see Mr. Belford. And you will tell him about Angela’s money. Is that quite clear?”

“Oh, all right,” said his lordship moodily. “All right, all right, all right.”

THE emotions of the Earl of Emsworth, as he sat next day facing his luncheon guest, James Bartholomew Belford, across a table in the main dining-room of the Senior Conservative Club, were not of the liveliest and most agreeable. It was bad enough to be in London at all on such a day of golden sunshine. To be charged with the task of blighting the romance of two young people for whom he entertained a warm regard was unpleasant to a degree.

For, now that he had given the matter thought, Lord Emsworth recalled that he had always liked this boy Belford. A pleasant lad, with, he remembered now, a healthy fondness for that rural existence which so appealed to himself. It occurred to Lord Emsworth, as it has occurred to so many people, that the distribution of money in this world was all wrong. Why should a man like pig-despising Heacham have a rent roll that ran into the tens of thousands, while this very deserving youngster had nothing?

These thoughts not only saddened Lord Emsworth—they embarrassed him. He hated unpleasantness, and it was suddenly borne in upon him that, after he had broken the news that Angela’s bit of capital was locked up and not likely to get loose, conversation with his young friend during the remainder of the lunch was likely to be somewhat difficult.

He made up his mind to postpone the revelation. During the meal, he decided, he would chat pleasantly of this and that; and then, later, while bidding his guest good-by, he would spring the thing on him and dive back into the recesses of the club.

Considerably cheered at having solved a delicate problem with such adroitness, he started to prattle.

“The gardens at Blandings,” he said, “are looking particularly attractive this summer. The rose garden—”

“How well I remember that rose garden,” said James Belford, sighing slightly and helping himself to Brussels sprouts. “It was there that Angela and I used to meet on summer mornings.”

Lord Emsworth blinked. This was not an encouraging start, but the Emsworths were a fighting clan. He had another try.

“I have seldom seen such a blaze of color as was to be witnessed there during the month of June. The place was a mass of flourishing Damasks and Ayrshires and—”

“Properly to appreciate roses,” said James Belford, “you want to see them as a setting for a girl like Angela. With her fair hair gleaming against the green leaves—”

“More Brussels sprouts, my dear fellow?”

“—and her little feet brushing the dew from the turf—”

“The cheese is good here. You must try our Stilton.”

“—she makes a rose garden seem a veritable paradise.”

“No doubt,” said Lord Emsworth. “No doubt. I am glad you appreciated my rose garden. At Blandings, of course, we have the natural advantage of loamy soil, rich in plant food and humus—”

“ANGELA tells me,” said James Belford, “that you have forbidden our marriage.”

Lord Emsworth choked dismally over his chicken. Directness of this kind, he told himself with a pang of self-pity, was the sort of thing young Englishmen picked up in America. In those energetic and forceful surroundings you learned to Talk Quick and Do It Now and all sorts of uncomfortable things.

“Er—well, yes, now you mention it, I believe some informal decision of that nature was arrived at. You see, my dear fellow, my sister Constance feels rather strongly—”

“I understand. I suppose she thinks I’m a sort of prodigal.”

“No, no, my dear fellow. She never said that. Wastrel was the term she employed.”

“Well, perhaps I did start out in business on those lines. But you can take it from me that when you find yourself employed on a farm in Nebraska belonging to an applejack-nourished patriarch with strong views on work and a good vocabulary, you soon develop a certain liveliness.”

“Are you employed on a farm?”

“I was employed on a farm.”

“Pigs?” said Lord Emsworth in a low, eager voice.

“Among other things.”

Lord Emsworth gulped. His fingers clutched at the tablecloth.

“Then, perhaps, my dear fellow, you can give me some advice. For the last two days my prize sow, Empress of Blandings, has declined all nourishment. And the agricultural show is on Wednesday week. I am distracted with anxiety.”

James Belford frowned thoughtfully.

“What does your pig man say about it?”

“My pig man was sent to prison two days ago— Two days!” For the first time the significance of the coincidence struck him. “You don’t think that can have anything to do with the animal’s loss of appetite?”

“Certainly. I imagine she is missing him and pining away because he isn’t there.”

Lord Emsworth was surprised. He had only a distant acquaintance with George Cyril Wellbeloved; but from what he had seen of him he had not credited him with this fatal fascination.

“She probably misses his evening call.”

Again his lordship found himself perplexed. He had had no notion that pigs were such sticklers for the formalities of social life.

“His call?”

“He must have given some special call when he wanted her to come to dinner. One of the first things you learn on a farm is hog-calling. Pigs are temperamental. Call them wrong, and they’ll starve before they’ll put on a nosebag. Call them right, and they’ll follow you to the ends of the earth with their mouths watering.

“I knew a man out in Nebraska who used to call his pigs by tapping on the edge of the trough with his wooden leg.”

“Did he, indeed?”

“But a most unfortunate thing happened. One evening, hearing a woodpecker at the top of a tree, they started shinning up it; and when the man came out he found them all lying in a circle with their necks broken.”

“This is no time for joking,” said Lord Emsworth, pained.

“I’m not joking. Solid fact. Ask anybody out there. But if you want information about hog-calling, you’ve come to the right man. I studied under Fred Patzel, the champion. I’ve known pork chops to leap from their plates when that man called ‘Pig-hoo-o-o-o-ey!’ ”

“Pig—?”

“—hoo-o-o-o-ey.”

“Pig-hoo-o-o-o-ey.”

“You haven’t got it quite right. The first syllable should be short and staccato, the second long and rising into a falsetto, high but true.”

“Pig-hoo-o-o-o-ey.”

“Pig-hoo-o-o-o-ey.”

“Pig-hoo-o-o-o-ey!” yodeled Lord Emsworth, flinging his head back and letting it go in a high, penetrating tenor voice, which caused ninety-three Senior Conservatives, lunching in the vicinity, to congeal into living statues of alarm and disapproval.

“More body to the ‘hoo,’ ” advised James Belford.

“Pig-hoo-o-o-o-ey!”

The Senior Conservative Club is one of the few places in London where lunchers are not accustomed to getting music with their meals. White-whiskered financiers gazed bleakly at bald-headed politicians, asking silently what was to be done about this. Bald-headed politicians stared back at white-whiskered financiers, replying in the language of the eye that they did not know. The general sentiment prevailing was a vague determination to write to the committee about it.

“Pig-hoo-o-o-o-ey!” caroled Lord Emsworth. And, as he did so, his eye fell on the clock over the mantelpiece. Its hands pointed to twenty minutes to two.

HE started convulsively. The best train in the day for Market Blandings was the one that left Paddington Station at 2 o’clock sharp. After that there was nothing till the five-five.

He was not a man who thought often, but, when he did, to think was with him to act. A moment later he was making for the door that led to the broad staircase.

Whispering the magic syllables, he sped to the cloakroom and retrieved his hat. Murmuring them over and over again, he sprang into a cab. He was still repeating them as the train moved out of the station; and he would doubtless have gone on repeating them all the way to Market Blandings, had he not, as was his invariable practice when traveling by rail, fallen asleep after the first ten minutes of the journey.

The stopping of the train at Swindon Junction awoke him with a start. He sat up, wondering, after his usual fashion on these occasions, who and where he was. Then he remembered his name. He remembered that he was on his way home from a visit to London. But what it was that you said to a pig when inviting it to have a bite of dinner, he had completely forgotten.

IT was the opinion of Lady Constance Keeble, expressed during dinner in the brief intervals when they were alone, and by means of silent telepathy when Beach, the butler, was adding his dignified presence to the proceedings, that her brother Clarence, in his expedition to London to put matters plainly to James Belford, had made an outstanding idiot of himself. There had been no need whatever to invite the man Belford to lunch; but, having invited him to lunch, to leave him sitting without having clearly stated that Angela would have no money for four years was the act of a congenital imbecile. Lady Constance had been aware ever since their childhood days that her brother had about as much sense as a—

Here Beach entered, superintending the bringing in of the savory, and she had been obliged to suspend her remarks.

This sort of conversation is never agreeable to a sensitive man, and his lordship had removed himself from the danger zone as soon as he could manage it. He was now seated in the library, sipping port and straining a brain which nature had never intended for hard exercise in an effort to bring back that word of magic of which his unfortunate habit of sleeping in trains had robbed him.

“Pig—”

He could remember as far as that; but of what avail was a single syllable? Besides, weak as his memory was, he could recall that the whole gist or nub of the thing lay in the syllable that followed.

Lord Emsworth finished his port and got up. He felt restless, stifled. The summer night seemed to call to him like some silver-voiced swineherd calling to his pig. Possibly, he thought, a breath of fresh air might stimulate his brain cells.

He wandered downstairs; and, having dug an old slouch hat out of the cupboard where he hid it to keep his sister Constance from impounding and burning it, he strode heavily into the garden.

He was pottering aimlessly to and fro in the parts adjacent to the rear of the castle when there appeared in his path a slender female form. He recognized it without pleasure.

Any unbiased judge would have said that his niece Angela, standing there in the soft, pale light, looked like some dainty spirit of the moon. Lord Emsworth was not an unbiased judge. To him Angela merely looked like trouble.

“Is that you, my dear?” he said nervously.

“Yes.”

“I didn’t see you at dinner.”

“I didn’t want any dinner. The food would have choked me. I can’t eat.”

“It’s precisely the same with my pig,” said his lordship. “She hasn’t touched food for two days. Young Belford tells me—”

INTO Angela’s queenly disdain there flashed a sudden animation.

“Have you seen Jimmy? What did he say?”

“That’s just what I can’t remember. It began with the word ‘pig’—”

“But after he had finished talking about you, I mean. Didn’t he say anything about coming down here?”

“Not that I remember.”

“I expect you weren’t listening. You’ve got a very annoying habit, Uncle Clarence,” said Angela maternally, “of switching your mind off and just going blah when people are talking to you. It gets you very much disliked on all sides. Didn’t Jimmy say anything about me?”

“I fancy so. Yes, I am nearly sure he did.”

“Well, what?”

“I cannot remember.”

There was a sharp clicking noise in the darkness. It was caused by Angela’s top front teeth meeting her bottom front teeth, and was followed by a sort of wordless exclamation.

“I wish you wouldn’t do that,” said Lord Emsworth plaintively.

“Do what?”

“Make clicking noises at me.”

“I will make clicking noises at you. You know perfectly well, Uncle Clarence, that you are behaving like a bohunkus.”

“A what?”

“A bohunkus,” explained his niece coldly, “is a very inferior sort of worm. Not the kind of worm that you see on lawns, which you can respect, but a really degraded species.”

“I wish you would go in, my dear,” said Lord Emsworth. “The night air may give you a chill.”

“I won’t go in. I came out here to look at the moon and think of Jimmy. What are you doing out here, if it comes to that?”

“I came here to think. I am greatly exercised about my pig, Empress of Blandings. For two days she has refused her food, and young Belford says she will not eat until she hears the proper call. He very kindly taught it to me, but unfortunately I have forgotten it.”

“I wonder you had the nerve to ask Jimmy to teach you pig calls, considering the way you’re treating him.”

“But—”

“And all I can say is that, if you remember this call of his and it makes the Empress eat, you ought to be ashamed of yourself if you still refuse to let me marry him.”

“My dear,” said Lord Emsworth earnestly, “if, through young Belford’s instrumentality, Empress of Blandings is induced to take nourishment, there is nothing I will refuse him.”

“Honor bright?”

“I give you my solemn word.”

“You won’t let Aunt Constance bully you out of it?”

Lord Emsworth drew himself up.

“Certainly not,” he said proudly. “I am always ready to listen to your Aunt Constance’s views, but there are certain matters where I claim the right to act according to my own judgment.” He paused and stood musing. “It began with the word ‘pig’—”

From somewhere near at hand music made itself heard. The servants’ hall, its day’s labors ended, was refreshing itself with the housekeeper’s gramophone. To Lord Emsworth the strains were merely an additional annoyance. He was not fond of music.

“Yes, I can distinctly recall as much as that. Pig—Pig—”

“WHO—”

Lord Emsworth leaped in the air. It was as if an electric shock had been applied to his person.

“WHO stole my heart away?” howled the gramophone. “WHO—?”

The peace of the summer night was shattered by a triumphant shout:

“Pig-HOO-o-o-o-ey!”

A window opened. A large bald head appeared. A dignified voice spoke:

“Who is there? Who is making that noise?”

“Beach!” cried Lord Emsworth. “Come out here at once.”

“Very good, your lordship.”

AND presently the beautiful night was made still more lovely by the added attraction of the butler’s presence.

“Beach, listen to this.”

“Very good, your lordship.”

“Pig-hoo-o-o-o-ey!”

“Very good, your lordship.”

“Now you do it.”

“I, your lordship?”

“Yes. It’s a way you call pigs.”

“I do not call pigs, your lordship,” said the butler coldly.

“What do you want Beach to do it for?” asked Angela.

“Two heads are better than one. If we both learn it, it will not matter should I forget it again.”

“By Jove, yes! Come on, Beach. Push it over the thorax!” urged the girl eagerly. “You don’t know it, but this is a matter of life and death. ’At-a-boy, Beach!”

It had been the butler’s intention, prefacing his remarks with the statement that he had been in service at the castle for eighteen years, to explain frigidly to Lord Emsworth that it was not his place to stand in the moonlight, practicing pig calls. If his lordship saw the matter from a different angle, than it was his painful duty to tender his resignation, to become effective one month from that day.

But the intervention of Angela made this impossible to a man of chivalry and heart. A paternal fondness for the girl, dating from the days when he had stooped to enacting—and very convincingly, too, for his was a figure that lent itself to the impersonation—the rôle of a hippopotamus for her childish amusement, checked the words he would have uttered.

She was looking at him with bright eyes, and even the rendering of pig noises seemed a small sacrifice to make for her sake.

“Very good, your lordship,” he said in a low voice. “I shall endeavor to give satisfaction.”

“Stout fellow, Beach! What’s the matter with Beach? He’s all right! Who’s all right? Beach is all right!” said Angela, and the butler bowed, feeling like a knight who has received the thanks of his lady.

“I would merely advance the suggestion, your lordship,” he said, “that we move a few steps farther away from the vicinity of the servants’ hall. If I were to be overheard, it would weaken my position as a disciplinary force.”

“What chumps we are!” cried Angela. “The place to do it is outside the Empress’ sty. Then, if it works, we’ll see it working.”

Lord Emsworth found this a little abstruse, but after a moment he got it.

“Angela,” he said, “you are a very intelligent girl. Where you get your brains from I don’t know. Not from my side of the family.”

THE residence of the Empress of Blandings looked very snug and attractive in the moonlight. But beneath even the beautiful things of life there is always an underlying madness. This was supplied in the present instance by a long, low trough, only too plainly full to the brim of succulent mash and acorns. The fast, obviously, was still in progress.

The sty stood some distance from the castle walls, so that there had been ample opportunity for Lord Emsworth to rehearse his little company during the journey. By the time they had ranged themselves against the rails, his two assistants had become absolutely letter-perfect.

After a moment, “Now!” said his lordship.

There floated out upon the summer night a strange, composite sound that sent the birds shooting off their perches like rockets. Angela’s clear soprano rang out like the voice of the Village Blacksmith’s daughter. Lord Emsworth contributed a reedy tenor. And the bass notes of Beach probably did more to startle the birds than any other item in the program.

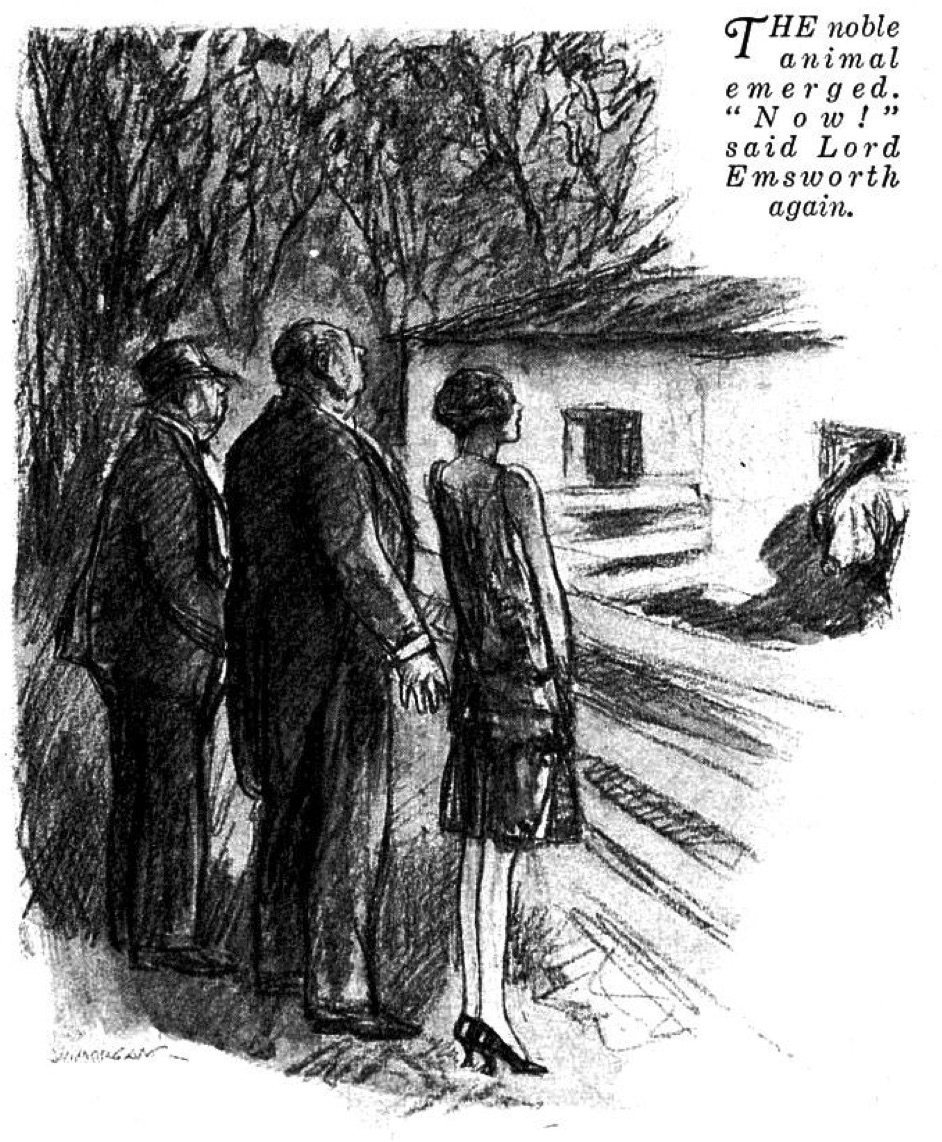

They paused and listened. Inside the Empress’ boudoir sounded the movement of a heavy body and an inquiring grunt. The next moment, the sacking that covered the doorway was pushed aside, and the noble animal emerged.

“Now!” said Lord Emsworth again.

Once more that musical cry shattered the silence of the night. But it brought no responsive movement from Empress of Blandings. She stood there, motionless, her nose elevated, her ears hanging down, her eyes everywhere but on the trough where, by rights, she should now have been digging in. A chill disappointment crept over Lord Emsworth, to be succeeded by a gust of petulant anger.

“I might have known it,” he said bitterly. “That young scoundrel was deceiving me.”

“He wasn’t!” cried Angela indignantly. “Was he, Beach?”

“Not knowing the circumstances, miss, I cannot venture an opinion.”

“Well, why has it no effect, then?” demanded Lord Emsworth.

“You can’t expect it to work right away. We’ve got her stirred up, haven’t we? She’s thinking it over, isn’t she? Once more will do the trick. Ready, Beach?”

“Quite ready, miss.”

“Then, when I say ‘three.’ And this time, Uncle Clarence, do please for goodness’ sake not yowl like you did before. It was enough to put any pig off. Let it come out quite easily and gracefully. Now, then; one, two—three!”

The echoes died away. As they did so, a voice spoke:

“Community singing?”

“Jimmy!” cried Angela, whisking round.

“Hullo, Angela. Hullo, Lord Emsworth. Hullo, Beach.”

“Good evening, sir. Happy to see you again.”

“Thanks. I’m spending a few days at the vicarage with my father.”

Lord Emsworth cut in peevishly upon these civilities.

“Young man,” he said, “what do you mean by telling me that my pig would respond to that cry? It does nothing of the kind.”

“You can’t have done it right.”

“I did it precisely as you instructed me. I have had, moreover, the assistance of Beach here and my niece Angela—”

“The future Mrs. Belford,” interjected the girl. “Jimmy darling, Uncle Clarence says—”

“Let’s hear a sample,” said the young man.

LORD EMSWORTH cleared his throat.

“Pig-hoo-o-o-o-ey!”

James Belford shook his head.

“Nothing like it,” he said. “You want to begin the ‘hoo’ in a low minor of two quarter notes in four-four time. From this build gradually to a higher note, until at last the voice is soaring in full crescendo, reaching F sharp on the natural scale and dwelling for two retarded half notes, then breaking into a shower of accidental grace notes.”

“God bless my soul!” said Lord Emsworth, appalled. “I shall never be able to do it.”

“Jimmy will do it for you,” said Angela. “Now that he’s engaged to me, he’ll be one of the family and always popping about here. He can do it every day till the show is over.”

James Belford nodded.

“I think that would be the wisest plan. You need a voice that has been trained in the open prairie. You need a manly, sunburned, wind-scorched voice, with a suggestion in it of the crackling of corn husks and the whisper of evening breezes in the fodder. Like this!”

James Belford swelled before their eyes like a young balloon. The muscles on his cheeks stood out, his forehead became corrugated, his ears seemed to shimmer. Then, at the very height of the tension, he let it go like, as the poet beautifully puts it, the sound of a great Amen.

“Pig-HOOOOOO-OOO-OOO-O-O-ey!”

They looked at him, awed. Slowly, fading off across hill and dale, the vast bellow died away. And suddenly, as it died, another, softer sound succeeded it—a sort of gulpy, gurgly, plobby, squishy, wofflesome sound, like a thousand eager men drinking soup in a foreign restaurant. And, as he heard it. Lord Emsworth uttered a cry of rapture.

The Empress was feeding.

the end

Annotations to this story as collected in volume form are on this site in the notes to Blandings Castle and Elsewhere.

Madame Eulalie’s Rare Plums

Madame Eulalie’s Rare Plums