Liberty, September 18, 1926

I

THE roof of the Sheridan Apartment House, near Washington Square, New York. Let us examine it. There will be stirring happenings on this roof in due season, and it is as well to know the ground.

The Sheridan stands in the heart of New York’s Bohemian and artistic quarter. If you threw a brick from any of its windows, you would be certain to brain some rising young interior decorator, some vorticist sculptor, or a writer of revolutionary vers libre. And a very good thing, too. Its roof, cozy, compact and ten stories above the street, is flat, paved with tiles and surrounded by a low wall, jutting up at one end of which is an iron structure—the fire escape. Climbing down this, should the emergency occur, you would find yourself in the open-air premises of the Purple Chicken restaurant—one of those numerous oases in this great city where, in spite of the law of prohibition, you can still, so the cognoscenti whisper, “always get it if they know you.”

On the other side of the roof, opposite the fire escape, stands what is technically known as a small bachelor apartment, “penthouse style.” It is a white walled, red tiled bungalow, and the small bachelor who owns it is a very estimable young man named George Finch, originally from East Gilead, Idaho, but now, owing to a substantial legacy from an uncle, a unit of New York’s Latin Quarter. For George, no longer being obliged to earn a living, has given his suppressed desires play by coming to the metropolis and trying his hand at painting. From boyhood he had always wanted to be an artist and now he is an artist, and probably the worst artist who ever put brush to canvas.

FOR the rest, that large round thing that looks like a captive balloon is the water tank. That small oblong thing that looks like a summerhouse is George Finch’s outdoor sleeping porch. Those things that look like potted shrubs are potted shrubs. That stoutish man sweeping with a broom is George’s valet, cook, and man-of-all-work, Mullett.

And this imposing figure with the square chin and the horn-rimmed spectacles that flash like jewels in the sun, is no less a person than J. Hamilton Beamish, author of the famous Beamish Booklets (“Read Them and Make the World Your Oyster”), which have done so much to teach the populace of the United States observation, perception, judgment, initiative, will power, decision, business acumen, resourcefulness, organization, directive ability, self-confidence, driving power, originality—and, in fact, practically everything else from poultry to poetry.

The first emotion which any student of the Booklets would have felt on seeing his mentor in the flesh—apart from that natural awe which falls upon us when we behold the great—would probably have been surprise at finding him so young. Hamilton Beamish was still in the early thirties. But the brain of Genius ripens quickly; and those who had the privilege of acquaintance with Mr. Beamish at the beginning of his career say that he knew everything there was to be known—or behaved as if he did—at ten.

Hamilton Beamish’s first act on reaching the roof of the Sheridan was to draw several deep breaths—through the nose, of course. Then, adjusting his glasses, he cast a flashing glance at Mullett; and, having inspected him for a moment, pursed his lips and shook his head.

“All wrong!” he said.

The words, delivered at a distance of two feet in the man’s immediate rear, were spoken in the sharp, resonant voice of one who Gets Things Done, which, in its essentials, is rather like the note of a seal barking for fish. The result was that Mullett, who was highly strung, sprang some eighteen inches into the air and swallowed his chewing gum. Owing to that great thinker’s practice of wearing No-Jar Rubber Soles (“They Save The Spine”), Mullett had had no warning of Mr. Beamish’s approach.

“All wrong!” repeated Mr. Beamish.

And when Hamilton Beamish said “All wrong!” it meant “All wrong!” He was a man who thought clearly and judged boldly, without vacillation. He called a Ford a Ford.

“Wrong, sir?” faltered Mullett, when, realizing that there had been no bomb outrage after all, he was able to speak.

“Wrong. Inefficient. Waste motion. From the muscular exertion which you are using on that broom you are obtaining a bare sixty-three or sixty-four per cent of result value. Correct this. Adjust your methods. Have you seen a policeman about here?”

“A policeman, sir?”

Hamilton Beamish clicked his tongue in annoyance. It was waste motion—but even efficiency experts have their feelings.

“A policeman. I said a policeman and I meant a policeman.”

“Were you expecting one, sir?”

“I was and I am.”

Mullett cleared his throat.

“Would he be wanting anything, sir?” he asked, a little nervously.

“He wants to become a poet. And I am going to make him one.”

“A poet, sir?”

“Why not? I could make a poet out of far less promising material. I could make a poet out of two sticks and a piece of orange peel, if they studied my booklet carefully. This fellow wrote to me, explaining his circumstances and expressing a wish to develop his higher self, and I became interested in his case and am giving him special tuition. He is coming up here today to look at the view and write a description of it in his own words. This I shall correct and criticize. A simple exercise in composition.”

“I see, sir.”

“He is ten minutes late. I trust he has some satisfactory explanation. Meanwhile, where is Mr. Finch? I would like to speak to him.”

“Mr. Finch is out, sir.”

“He always seems to be out nowadays. When do you expect him back?”

“I don’t know, sir. It all depends on the young lady.”

“Mr. Finch is out with a young lady!”

“No, sir. Just gone to look at one.”

“To look at one!” The author of the Booklets clicked his tongue once more. “You are driveling, Mullett. Never drivel—it is dissipation of energy.”

“It’s true, Mr. Beamish. He has never spoken to this lady—only looked at her.”

“Explain yourself.”

“Well, sir, it’s like this: I’d noticed for some time past that Mr. Finch had been getting what you might call choosey about his clothes.”

“What do you mean—choosey?”

“Particular, sir.”

“Then say particular, Mullett. Avoid jargon. Strive for the Word Beautiful. Read my booklet on Pure English. Well?”

“PARTICULAR about his clothes, sir, I noticed Mr. Finch had been getting. Twice he had started out in the blue with the invisible pink twill and then suddenly stopped at the door of the elevator and gone back and changed into the dove-gray. And his ties, Mr. Beamish. There was no satisfying him. So I said to myself, ‘Hot dog!’ ”

“You said what?”

“Hot dog, Mr. Beamish.”

“And why did you use this revolting expression?”

“What I meant was, sir, that I reckoned I knew what was at the bottom of all this.”

“And were you right in this reckoning?”

A coy look came into Mullett’s face.

“Yes, sir. You see, Mr. Finch’s behavior having aroused my curiosity, I took the liberty of following him one afternoon. I followed him to Seventy-ninth Street, east.”

“And then?”

“He walked up and down outside one of those big houses there, and presently a young lady came out. Mr. Finch looked at her and she passed by. Then Mr. Finch looked after her, sighed, and came away. The next afternoon I again took the liberty of following him and the same thing happened. Only this time the young lady was coming in from a ride in the Park. Mr. Finch looked at her, and she passed into the house. Mr. Finch then remained staring at the house so long that I was obliged to leave him, having the dinner to prepare. And what I meant, sir, when I said that the duration of Mr. Finch’s absence depended on the young lady, was that he stops longer when she comes in than when she goes out. He might be back any minute, or he might not be back till dinner time.”

Hamilton Beamish frowned.

“I don’t like this, Mullett.”

“No, sir?”

“It sounds like love at first sight.”

“Yes, sir.”

“Have you read my booklet on the Marriage Sane?”

“Well, sir, what with one thing and another and being very busy about the house——”

“In that booklet I argue very strongly against love at first sight.”

“Do you indeed, sir?”

“I expose it for the mere delirious folly it is. Mating should be a reasoned process, ruled by the intellect. What sort of a young lady is this young lady?”

“Very attractive, sir.”

“Tall? Short? Large? Small?”

“Small, sir. Small and roly-poly.”

Hamilton Beamish shuddered violently.

“Don’t use that nauseating adjective! Are you trying to convey the idea that she is short and stout?”

“Oh, no, sir, not stout; just nice and plump; what I should describe as cuddly.”

“Mullett,” said Hamilton Beamish, “you will not, in my presence and while I have my strength, describe any of God’s creatures as cuddly. Where you picked it up, I cannot say, but you have the most abhorrent vocabulary I have ever encountered— What’s the matter?”

The valet was looking past him with an expression of deep concern.

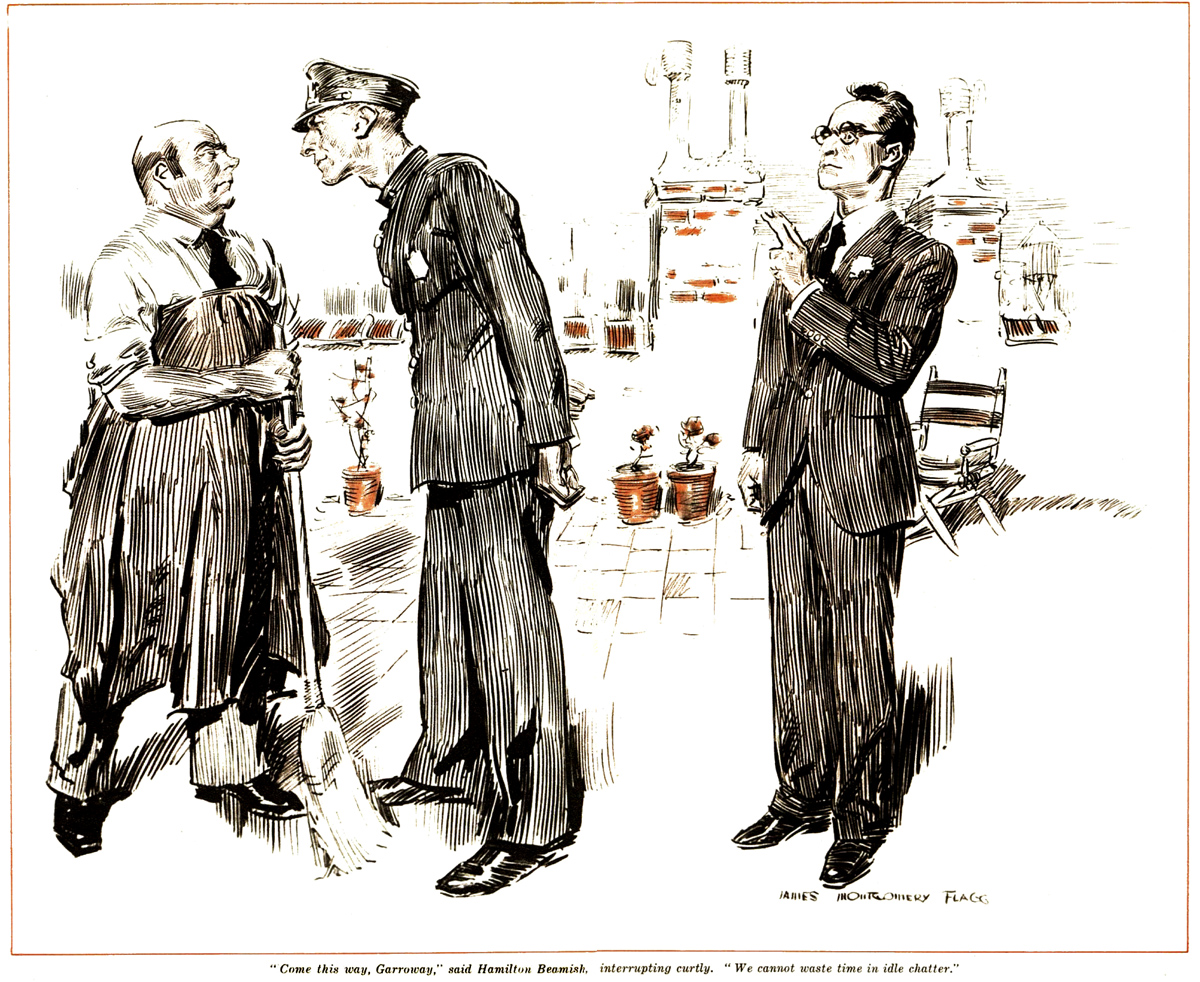

“Why are you making faces, Mullett?” Hamilton Beamish turned. “Ah, Garroway,” he said, “there you are at last. You should have been here ten minutes ago.”

A policeman had come out on to the roof.

II

THE policeman touched his cap. He was a long, stringy policeman, who flowed out of his uniform at odd spots, as if Nature, setting out to make a constable, had had a good deal of material left over which it had not liked to throw away but hardly seemed able to fit neatly into the general scheme. He had large, knobby wrists of a geranium hue and just that extra four or five inches of neck which disqualify a man for high honors in a beauty competition. His eyes were mild and blue, and from certain angles he seemed all Adam’s apple.

“I must apologize for being late, Mr. Beamish,” he said. “I was detained at the station house.” He looked at Mullett uncertainly. “I think I have met this gentleman?”

“No, you haven’t,” said Mullett quickly.

“Your face seems very familiar.”

“Never seen me in your life.”

“Come this way, Garroway,” said Hamilton Beamish, interrupting curtly. “We cannot waste time in idle chatter.” He led the officer to the edge of the roof and swept his hand round in a broad gesture. “Now, tell me. What do you see?”

The policeman’s eye sought the depths.

“That’s the Purple Chicken down there,” he said. “One of these days that joint will get pinched.”

“Garroway!”

“Sir?”

“For some little time I have been endeavoring to instruct you in the principles of pure English. My efforts seem to have been wasted.”

The policeman blushed.

“I beg your pardon, Mr. Beamish. One keeps slipping into it. It’s the effect of mixing with the boys—with my colleagues—at the station house. They are very lax. What I meant was that in the near future there was likely to be a raid conducted on the premises of the Purple Chicken, sir. It has been drawn to our attention that the Purple Chicken still purveys alcoholic liquors.”

“Never mind the Purple Chicken. I brought you up here to see what you could do in the way of a word-picture of the view. The first thing a poet needs is to develop his powers of observation. How does it strike you?”

The policeman gazed mildly at the horizon. His eye flitted from the roof tops of the city, spreading away in the distance, to the Hudson, glittering in the sun. He shifted his Adam’s apple up and down two or three times, as one in deep thought.

“It looks very pretty, sir,” he said at length.

“Pretty?” Hamilton Beamish’s eyes flashed. You would never have thought, to look at him, that the J. in his name stood for James, and that there had once been people who had called him Jimmy. “It isn’t pretty at all.”

“No, sir?”

“It’s stark.”

“Stark, sir?”

“Stark and grim. It makes your heart ache. You think of all the sorrow and sordid gloom which those roofs conceal, and your heart bleeds. I may as well tell you, here and now, that if you are going about the place thinking things pretty, you will never make a modern poet. Be poignant, man, be poignant!”

“Yes, sir. I will, indeed, sir.”

“Well, take your notebook and jot down a description of what you see. I must go down to my apartment and attend to one or two things. Look me up tomorrow.”

“Yes, sir. Excuse me, sir, but who is that gentleman over there with the broom? His face seemed so very familiar.”

“His name is Mullett. He works for my friend, George Finch. But never mind about Mullett. Stick to your work. Concentrate!”

“Yes, sir. Most certainly, Mr. Beamish.”

He looked with doglike devotion at the thinker, then gravely bent himself to his task.

Hamilton Beamish turned on his No-Jar rubber heel, and passed through the door.

III

FOLLOWING his departure, silence reigned some minutes on the roof of the Sheridan. Mullett resumed sweeping, and Officer Garroway scribbled industriously. But after about a quarter of an hour, feeling apparently that he had observed all there was to observe, he put book and pencil away and, approaching Mullett, subjected him to a mild but penetrating scrutiny.

“I feel convinced, Mr. Mullett,” he said, “that I have seen your face before.”

“And I say you haven’t,” said the valet testily.

“Perhaps you have a brother, Mr. Mullett, who resembles you?”

“Dozens. And even mother couldn’t tell us apart.”

The policeman sighed.

“I am an orphan,” he said, “without brothers or sisters.”

“Too bad.”

“Stark,” agreed the policeman. “Very stark and poignant. You don’t think I could have seen a photograph of you anywhere, Mr. Mullett?”

“Haven’t been taken for years.”

“Strange!” said Officer Garroway meditatively. Somehow—I cannot tell why—I seem to associate your face with a photograph.”

“Not your busy day, this, is it?”

“I am off duty at the moment. I seem to see a photograph—several photographs—in some sort of collection.”

There could be no doubt by now that Mullett had begun to find the conversation difficult. He looked like a man who has a favorite aunt in Poughkeepsie and is worried about her asthma. He was turning to go, when there came out on to the roof from the door leading to the stairs a young man in a suit of dove-gray.

“Mullett!” he called.

The other hurried toward him, leaving the officer staring pensively at his spacious feet.

“Yes, Mr. Finch?”

It is impossible for a historian with a nice sense of value not to recognize the entry of George Finch, following immediately after that of J. Hamilton Beamish, as an anti-climax. Mr. Beamish filled the eye. An aura of authority went before him as the cloud of fire went before the Israelites in the desert. When you met J. Hamilton Beamish, something like a steam hammer seemed to hit your consciousness and stun it long before he came within speaking distance. In the case of George Finch nothing of this kind happened.

George looked what he was—a nice, young, small bachelor, of the type you see bobbing about the place on every side. One glance at him was enough to tell you that he had never written a booklet and never would write a booklet. In figure he was slim and slight; as to the face, pleasant and undistinguished. He had brown eyes which in certain circumstances could look like those of a stricken sheep; and his hair was of a light chestnut color. It was possible to see his hair clearly, for he was not wearing his hat, but carrying it in his hand.

HE was carrying it reverently, as if he attached a high value to it. And this was strange, for it was not much of a hat. Once it may have been, but now it looked as if it had been trodden on and kicked about.

“Mullett,” he said, regarding this relic with a dreamy eye, “take this hat and put it away.”

“Throw it away, sir?”

“Good heavens, no! Put it away—very carefully. Have you any tissue paper?”

“Yes, sir.”

“Then wrap it up very carefully in tissue paper and leave it on the table in my sitting-room.”

“Very good, sir.”

“Pardon me for interrupting,” said a deprecating voice behind him, “but might I request a moment of your time, Mr. Finch?”

Officer Garroway had left his fixed point and was standing in an attitude that seemed to suggest embarrassment. His mild eyes wore a somewhat timid expression.

“Forgive me if I intrude,” said Officer Garroway.

“Not at all,” said George.

“I am a policeman, sir.”

“So I see.”

“And,” said Officer Garroway sadly, “I have a rather disagreeable duty to perform, I fear. I would avoid it, if I could reconcile the act with my conscience, but duty is duty. One of the drawbacks to a policeman’s life, Mr. Finch, is that it is not easy for him always to do the gentlemanly thing.”

“No doubt,” said George.

Mullett swallowed apprehensively. The hunted look had come back to his face. Officer Garroway eyed him with solicitude.

“I would like to preface my remarks,” he proceeded, “by saying that I have no personal animus against Mr. Mullett. I have seen nothing in my brief acquaintance with Mr. Mullett that leads me to suppose that he is not a pleasant companion and zealous in the performance of his work. Nevertheless, I think it right that you should know that he is an ex-convict.”

“An ex-convict!”

“Reformed,” said Mullett hastily.

“As to that, I cannot say,” said Officer Garroway. “I can but speak of what I know. Very possibly, as he asserts, Mr. Mullett is a reformed character. But this does not alter the fact that he has done his bit of time; and in pursuance of my duty I can scarcely refrain from mentioning this to the gentleman who is his present employer. The moment I was introduced to him, I detected something oddly familiar about Mr. Mullett’s face, and I have just recollected that I recently saw a photograph of him in the Rogues’ Gallery at Headquarters. You are possibly aware, sir, that convicted criminals are ‘mugged’—that is to say, photographed in various positions—at the commencement of their term of incarceration. This was done to Mr. Mullett some eighteen months ago, when he was sentenced to a year’s imprisonment for an inside burglary job. May I ask how Mr. Mullett came to be in your employment?”

“He was sent to me by Mr. Beamish. Mr. Hamilton Beamish.”

“In that case, sir, I have nothing further to say,” said the policeman, bowing at the honored name. “No doubt Mr. Beamish had excellent reasons for recommending Mr. Mullett. And, of course, as Mr. Mullett has long since expiated his offence, I need scarcely say that we of the police have nothing against him. I must now leave you, as my duties compel me to return to the station house. Good afternoon, Mr. Finch.”

“Good afternoon.”

“Good day, Mr. Mullett. Pleased to have met you. You did not by any chance run into a young fellow named Joe the Gorilla while you were in residence at Sing Sing? No? I’m sorry. He came from my home town. I should have liked to have had news of Joe.”

OFFICER GARROWAY’S departure was followed by a lengthy silence. George Finch shuffled his feet awkwardly. He was an amiable young man, and disliked unpleasant scenes. He looked at Mullett. Mullett looked at the sky.

“Er—Mullett,” said George.

“Sir?”

“This is rather unfortunate.”

“Most unpleasant for all concerned, sir.”

“I think Mr. Beamish might have told me.”

“No doubt he considered it unnecessary, sir. Being aware that I had reformed.”

“Yes, but even so. Er—Mullett.”

“Sir?”

“The officer spoke of an inside burglary job. What was your exact—er—line?”

“I used to get a place as a valet, sir, wait till I saw my chance, and then skin out with everything I could lay hands on.”

“You did, did you?”

“Yes, sir.”

“Well, I do think Mr. Beamish might have dropped me a quiet hint. Good heavens! I may have been putting temptation in your way for weeks.”

“You have, sir,—serious temptation. But I welcome temptation, Mr. Finch. Every time I’m left alone with your pearl studs, I have a bout with the Tempter. ‘Why don’t you take them, Mullett?’ he says to me. ‘Why don’t you take them?’ It’s splendid moral exercise, sir.”

“I suppose so.”

“Yes, sir; it’s awful what that Tempter will suggest to me. Sometimes, when you’re lying asleep, he says ‘Slip a sponge of chloroform under his nose, Mullett, and clear out with the swag!’ Just imagine it, sir.”

“I am imagining it.”

“But I win every time, sir. I’ve not lost one fight with that old Tempter since I’ve been in your employment, Mr. Finch.”

“All the same, I don’t believe you’re going to remain in my employment, Mullett.”

Mullett inclined his head resignedly.

“I was afraid of this, sir. The moment that flat-footed cop came on to this roof I had a presentiment that there was going to be trouble. But I should appreciate it very much if you could see your way to reconsider, sir. I can assure you that I have completely reformed.”

“Religion?”

“No, sir. Love.”

The word seemed to touch some hidden chord in George Finch. The stern, set look vanished from his face. He gazed at his companion almost meltingly.

“Mullett! Do you love?”

“I do, indeed, sir. Fanny’s her name, sir. Fanny Welch. She’s a pickpocket.”

“A pickpocket!”

“Yes, sir. And one of the smartest girls in the business. She could take your watch out of your pocket and you’d be prepared to swear she hadn’t been within a yard of you. It’s an art, sir. But she’s promised to go straight, if I will, and now I’m saving up to buy the furniture. So I do hope, sir, that you will reconsider. It would set me back if I fell out of a place just now.”

George wrinkled his forehead.

“I oughtn’t to.”

“But you will, sir?”

“It’s weak of me.”

“Not it, sir. Christian, I call it.”

George pondered.

“How long have you been with me, Mullett?”

“Just on a month, sir.”

“And my pearl studs are still there?”

“Still in the drawer, sir.”

“All right, Mullett. You can stay.”

“Thank you very much indeed, sir.”

THERE was a silence. The setting sun flung a carpet of gold across the roof. It was the hour at which men become confidential.

“Love is very wonderful, Mullett!” said George Finch.

“Makes the world go round, I say, sir.”

“Mullett.”

“Sir?”

“Shall I tell you something?”

“If you please, sir.”

“Mullett,” said George Finch, “I, too, love.”

“You surprise me, sir.”

“You may have noticed that I have been fussy about my clothing of late, Mullett?”

“Oh, no, sir.”

“Well, I have been, and that was the reason. She lives on East Seventy-ninth Street, Mullett. I saw her first, lunching at the Plaza with a woman who looked like Catherine of Russia. Her mother, no doubt.”

“Very possibly, sir.”

“I followed her home— I don’t know why I am telling you this, Mullett.”

“No, sir.”

“Since then I have haunted the sidewalk outside her house. Do you know East Seventy-ninth Street?”

“Never been there, sir.”

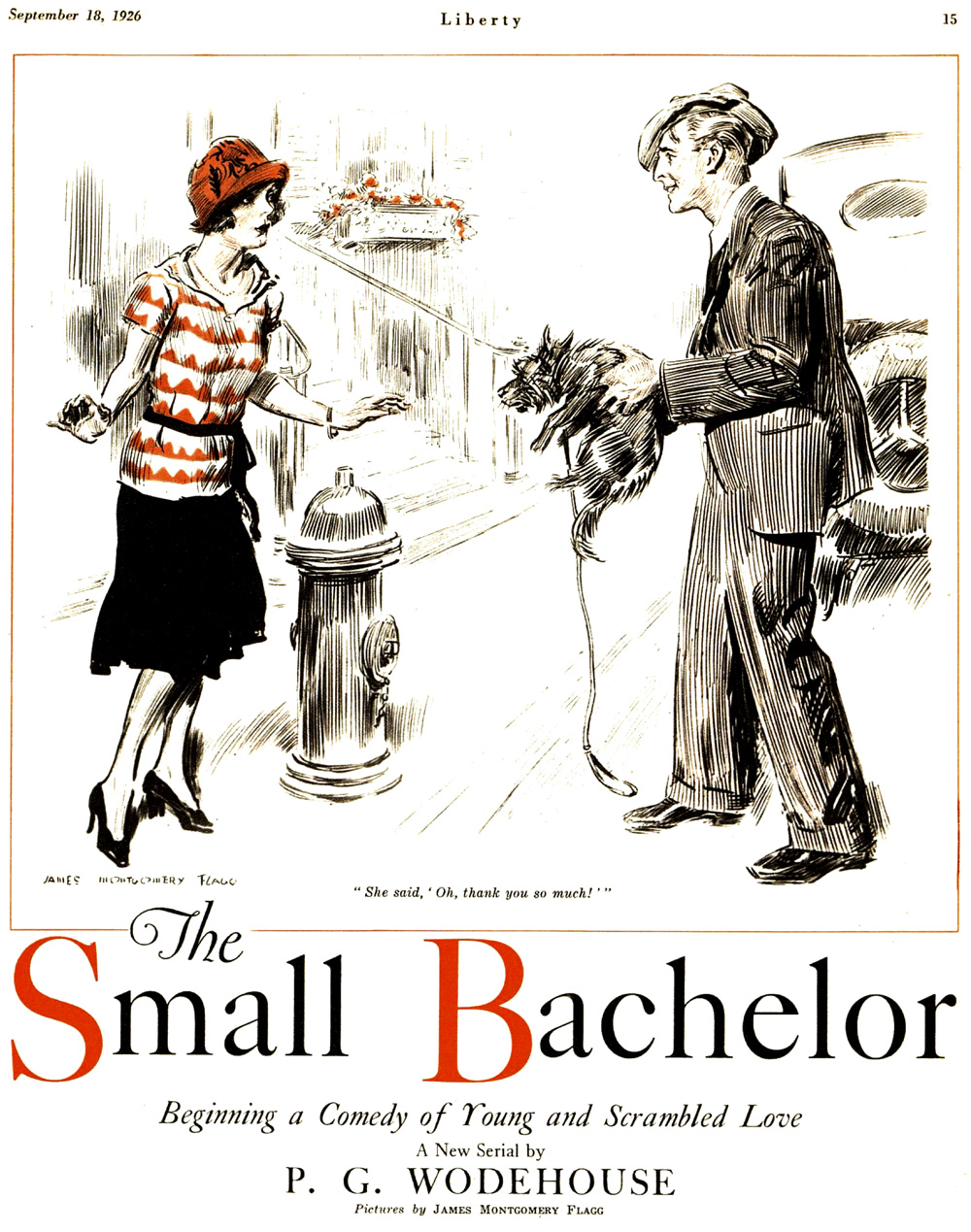

“Well, fortunately, it is not a much frequented thoroughfare, or I should have been arrested for loitering. Until today I have never spoken to her, Mullett.”

“But you did today, sir?”

“Yes. Or, rather, she spoke to me. She has a voice like the fluting of young birds in the springtime, Mullett.”

“Indeed, sir?”

“Yes, this hat that you see in my hand was trodden on by her. This very hat.”

“And then, sir?”

“In the excitement of the moment she dropped the leash. And the Scotch terrier ran off round the corner in the direction of Brooklyn. I went in pursuit, and succeeded in capturing it in Lexington Avenue. My hat dropped off again and was run over by a taxi-cab. But I retained my hold of the leash, and eventually restored the dog to its mistress. She said—and I want you to notice this very carefully, Mullett—she said ‘Oh, thank you so much!’ ”

“Did she, indeed, sir?”

“She did. Not merely ‘Thank you!’ or ‘Oh, thank you!’ but ‘Oh, thank you so much!’ ” George Finch fixed a penetrating stare on his employee. “I think that is significant, Mullett.”

“Extremely, sir.”

“If she had wished to end the acquaintance then and there, would she have spoken so warmly?”

“Impossible, sir.”

“And I’ve not told you all. Having said ‘Oh, thank you so much!’ she added: ‘He is a naughty dog, isn’t he?’ You get the extraordinary subtlety of that, Mullett? The words ‘He is a naughty dog’ would have been a mere statement. But by adding ‘isn’t he?’ she invited my opinion. She gave me to understand that she would welcome discussion. Do you know what I am going to do, directly I have dressed, Mullett?”

“Dine, sir?”

“Dine!” George shuddered. “No! There are moments when the thought of food is an outrage to everything that raises Man above the level of the beasts. As soon as I have dressed—and I shall dress very carefully—I am going to return to East Seventy-ninth Street and I am going to ring the doorbell and I am going to go straight in and inquire after the dog—hope it is none the worse for its adventure, and so on. After all, it is only the civil thing. I mean these Scotch terriers—delicate, highly strung animals—never can tell what effect unusual excitement may have on them. Yes, Mullett, that is what I propose to do. Brush my dress clothes as you have never brushed them before.”

“Very good, sir.”

“Put me out a selection of ties—say a dozen.”

“Yes, sir.”

“And—did the bootlegger call this morning?”

“Yes, sir.”

“Then mix me a very strong whisky and soda, Mullett,” said George Finch. “Whatever happens, I must be at my best tonight.”

IV

TO George, sunk in a golden reverie, there entered some few minutes later, jarring him back to life, a pair of three-pound dumb-bells, which shot abruptly out of the unknown and came trundling across the roof at him with a clumping sound that would have disconcerted Romeo. They were followed by J. Hamilton Beamish on all fours. Hamilton Beamish, who believed in the healthy body as well as the sound mind, always did half an hour’s open-air work with the bells of an evening and, not for the first time, he had tripped over the top stair.

He recovered his balance, his dumb-bells, and his spectacles in three labor-saving movements; and with the aid of the last named was enabled to perceive George.

“Oh, there you are!” said Beamish.

“Yes,” said George, “and——”

“What’s all this I hear from Mullett?” asked Hamilton Beamish.

“What,” inquired George simultaneously, “is all this I hear from Mullett?”

“Mullett says you’re fooling about after some girl uptown.”

“Mullett says you knew he was an ex-convict when you recommended him to me.”

HAMILTON BEAMISH decided to dispose of this triviality before going on to more serious business.

“Certainly,” he said. “Didn’t you read my series in the Yale Review on the Problem of the Reformed Criminal? I point out very clearly that there is nobody with such a strong bias towards honesty as the man who has just come out of prison. It stands to reason. If you had been laid up for a year in hospital as the result of jumping off this roof, what would be the one outdoor sport in which, on emerging, you would be most reluctant to indulge? Jumping off roofs, undoubtedly.”

George continued to frown in a dissatisfied way.

“That’s all very well, but a fellow doesn’t want ex-convicts hanging about.”

“Nonsense! You must rid yourself of this old-fashioned prejudice against men who have been in Sing Sing. Try to look on the place as a sort of university which fits its graduates for the problems of the world without. Morally speaking, such men are the student body. You have no fault to find with Mullett, have you?”

“No, I can’t say I have.”

“Does his work well?”

“Yes.”

“Not stolen anything from you?”

“No.”

“Then why worry? Dismiss the man from your mind. And now let me hear all about this girl of yours.”

“How do you know anything about it?”

“Mullett told me.”

“How did he know?”

“He followed you a couple of afternoons and saw all.”

George turned pink.

“I’ll fire that man. The snake!”

“You will do nothing of the kind. He acted as he did from pure zeal and faithfulness. He saw you go out muttering to yourself.”

“Did I mutter?” said George, startled.

“Certainly you muttered. You muttered, and you were exceedingly strange in your manner. So naturally Mullett, good, zealous fellow, followed you to see that you came to no harm. He reports that you spend a large part of your leisure goggling at some girl in Seventy-ninth Street, east.”

George’s pink face turned a shade pinker. A sullen look came into it.

“Well, what about it?”

“That’s what I want to know—what about it?”

“Why shouldn’t I goggle?”

“Why should you?”

“Because,” said George Finch, looking like a stuffed frog, “I love her.”

“Nonsense!”

“It isn’t nonsense.”

“Have you ever read my booklet on the Marriage Sane?”

“No, I haven’t.”

“I show there that love is a reasoned emotion that springs from mutual knowledge, increasing over an extended period of time and a community of tastes. How can you love a girl when you have never spoken to her and don’t even know her name?”

“I do know her name.”

“How?”

“I looked through the telephone directory till I found out who lived at Number Sixteen, East Seventy-ninth Street. It took me about a week, because——”

“Sixteen East Seventy-ninth Street? You don’t mean that this girl you’ve been staring at is little Molly Waddington?”

George started.

“Waddington is the name, certainly. That’s why I was such an infernal time getting to it in the book. Waddington, Sigsbee H.” George choked emotionally, and gazed at his friend with awed eyes. “Hamilton! Hammy, old man! You—you don’t mean to say you actually know her? Not positively know her?”

“Of course I know her. Know her intimately. Many’s the time I’ve seen her in her bathtub.”

George quivered from head to foot.

“It’s a lie! A foul and contemptible——”

“When she was a child.”

“Oh, when she was a child!” George became calmer. “Do you mean to say you’ve known her since she was a child? Why, then you must be in love with her yourself.”

“Nothing of the kind.”

“You stand there and tell me,” said George, incredulously, “that you have known this wonderful girl for many years and are not in love with her?”

“I do.”

GEORGE regarded his friend with a gentle pity. He could only explain this extraordinary statement by supposing that there was a kink in Hamilton Beamish. Sad, for in so many ways he was such a fine fellow.

“The sight of her has never made you feel that, to win one smile, you could scale the skies and pluck out the stars and lay them at her feet?”

“Certainly not. Indeed, when you consider that the nearest star is millions of——”

“All right,” said George. “All right. Let it go. And now,” he went on, simply, “tell me all about her, and her people, her house, her dog, and what she was like as a child, when she first bobbed her hair, and who is her favorite poet, and where she went to school, and what she likes for breakfast.”

Hamilton Beamish reflected.

“Well, I first knew Molly when her mother was alive.”

“Her mother is alive. I’ve seen her. A woman who looks like Catherine of Russia.”

“That’s her stepmother. Sigsbee H. married again a couple of years ago.”

“Tell me about Sigsbee H.”

J. Hamilton Beamish twirled a dumb-bell thoughtfully.

You’ll be roaring every minute as the complications of this yarn grow more intricate. How can the inoffensive George Finch storm the impregnable defenses of a mansion in East Seventy-ninth Street? But a young man in love is undaunted by the most fearsome perils. Next week’s installment carries a guarantee of twenty minutes’ unrestrained mirth.

Printer’s errors corrected above:

IV: Magazine had “across the room”; corrected to “across the roof”.

Madame Eulalie’s Rare Plums

Madame Eulalie’s Rare Plums