Maclean’s Magazine, November 1, 1921

SALLY stared at Ginger Kemp’s vermilion profile in frank amazement. Ginger, she had realized by this time, was in many ways a surprising young man, but she had not expected him to be so surprising as this.

“Marry you!”

“You know what I mean.”

“Well, yes, I suppose I do. You allude to the holy state. Yes, I know what you mean.”

“Then how about it?”

Sally began to regain her composure. Her sense of humor was tickled. She looked at Ginger gravely. He did not meet her eye, but continued to drink in the uniformed official, who was by now so carried away by the romance of it all that he had begun to hum a love ballad under his breath. The official could not hear what they were saying, and would not have been able to understand it even if he could have heard, but he was an expert in the language of the eyes.

“But isn’t this—don’t think I’m trying to make difficulties—isn’t this a little sudden?”

“It’s got to be sudden,” said Ginger Kemp complainingly. “I thought you were going to be here for weeks.”

“But, my infant, my babe, has it occurred to you that we are practically strangers?” She patted his hand tolerantly, causing the uniformed official to heave a tender sigh. “I see what has happened,” she said. “You’re mistaking me for some other girl, some girl you know really well and were properly introduced to. Take a good look at me and you’ll see.”

“If I take a good look at you,” said Ginger, feverishly, “I’m dashed if I’ll answer for the consequences.”

“And this is the man I was going to lecture on Enterprise!”

“You’re the most wonderful girl I’ve ever met, dash it!” said Ginger, his gaze still riveted on the official by the door. “I dare say it is sudden. I can’t help that. I fell in love with you the moment I saw you, and there you are!”

“But—”

“Now, look here. I know I’m not much of a chap and all that, but—well, I’ve just won the deuce of a lot of money in there.”

“Would you buy me with your gold?”

“I mean to say, we should have enough to start on, and—of course I’ve made an infernal hash of everything I’ve tried up till now, but there must be something I can do and you can jolly well bet I’d have a goodish stab at it. I mean to say, with you to buck me up and so forth, don’t you know. Well, I mean—”

“Has it struck you that I may already be engaged to someone else?”

“Oh, golly! Are you?”

For the first time he turned and faced her, and there was a look in his eyes which touched Sally and drove all sense of the ludicrous out of her. Absurd as it was, this man was really serious.

“Well, yes, as a matter of fact, I am,” she said soberly.

Ginger Kemp bit his lip, and for a moment was silent. “Oh, well, that’s torn it!” he said at last.

SALLY was aware of an emotion too complex for analysis. There was pity in it, but amusement too. The emotion, though she did not recognize it, was maternal. Mothers, listening to their children pleading with engaging absurdity for something wholly out of their power to bestow, feel that same wavering between tears and laughter. Sally wanted to pick Ginger up and kiss him. The one thing she could not do was to look on him, sorry as she was for him, as a reasonable, grown-up man.

“You don’t really mean it, you know.”

“Don’t I!” said Ginger hollowly. “Oh, don’t I!”

“You can’t! There isn’t such a thing in real life as love at first sight. Love’s a thing that comes when you know a person well and—” She paused. It had just occurred to her that she was hardly the girl to lecture in this strain. Her own love for Gerald Foster had been sufficiently sudden, even instantaneous. What did she know of Gerald except that she loved him! They had become engaged within two weeks of their first meeting. She found this recollection damping to her eloquence, and ended by saying tamely: “It’s ridiculous.”

Ginger had simmered down to a mood of melancholy resignation. “I couldn’t have expected you to care for me, I suppose, anyway,” he said somberly. “I’m not much of a chap.”

It was just the diversion from the theme under discussion which Sally had been longing to find. She welcomed the chance of continuing the conversation on a less intimate and sentimental note.

“That’s exactly what I wanted to talk to you about,” she said, seizing the opportunity offered by this display of humility. “I’ve been looking for you all day to go on with what I was starting to say in the elevator last night when we were interrupted. Do you mind if I talk to you like an aunt—or a sister, suppose we say? Really, the best plan would be for you to adopt me as an honorary sister. What do you think?”

Ginger did not appear noticeably elated at the suggested relationship.

“Because I really do take a tremendous interest in you.”

Ginger brightened. “That’s awfully good of you.”

“I’m going to speak words of wisdom. Ginger, why don’t you brace up?”

“Brace up?”

“Yes, stiffen your backbone and stick out your chin and square your elbows and really amount to something. Why do you simply flop about and do nothing and leave everything to what you call ‘the family’? Why do you have to be helped all the time? Why don’t you help yourself? Why do you have to have jobs found for you? Why don’t you rush out and get one? Why do you have to worry about what ‘the family’ thinks of you? Why don’t you make yourself independent of them? . . . By the way I hope you’re fond of conundrums. Because I’m asking a good many, aren’t I!——I know you had hard luck, suddenly finding yourself without money, and all that, but, good heavens, everybody else in the world who has ever done anything has been broke at one time or another. It’s part of the fun. You’ll never get anywhere by letting yourself be picked up by the family like—like a floppy Newfoundland puppy—and dumped down in any old place that happens to suit them. A job’s a thing you’ve got to choose for yourself and get for yourself. Think what you can do—there must be something—and then go at it with a snort and grab it and hold it down and teach it to take a joke.”

GINGER KEMP did not reply for a moment. He seemed greatly impressed. “When you talk quick,” he said at length in a serious, meditative voice, “your nose sort of goes all squiggly. Ripping it looks!”

Sally uttered an indignant cry. “Do you mean to say you haven’t been listening to a word I’ve been saying?” she demanded.

“Oh, rather! Oh, by Jove, yes.”

“Well, what did I say?”

“You—er. . . . And your eyes sort of shine too.”

“Never mind my eyes. What did I say?”

“You told me,” said Ginger on reflection, “to get a job.”

“Well, yes. I put it much better than that, but that’s what it amounted to, I suppose. All right, then. I’m glad you—”

Ginger was eyeing her with mournful devotion. “I say,” he interrupted, “I wish you’d let me write to you. Letters, I mean, and all that. I have an idea it would kind of buck me up.”

“You won’t have time for writing letters.”

“I’ll have time to write them to you. You haven’t an address or anything of that sort in America, have you, by any chance? I mean, so that I’d know where to write to.”

“I can give you an address which will always find me.” She told him the number and street of Mrs. Meecher’s boarding house, and he wrote them down reverently on his shirt cuff. “Yes, on second thoughts, do write,” she said. “Of course I shall want to know how you’ve got on. I—oh, my goodness! That clock’s not right?”

“Just about. What time does your train go?”

“Go! It’s gone! Or at least it goes in about two seconds.” She made a rush for the swing door, to the confusion of the uniformed official who had not been expecting this sudden activity. “Good-by, Ginger. Write to me and remember what I said.”

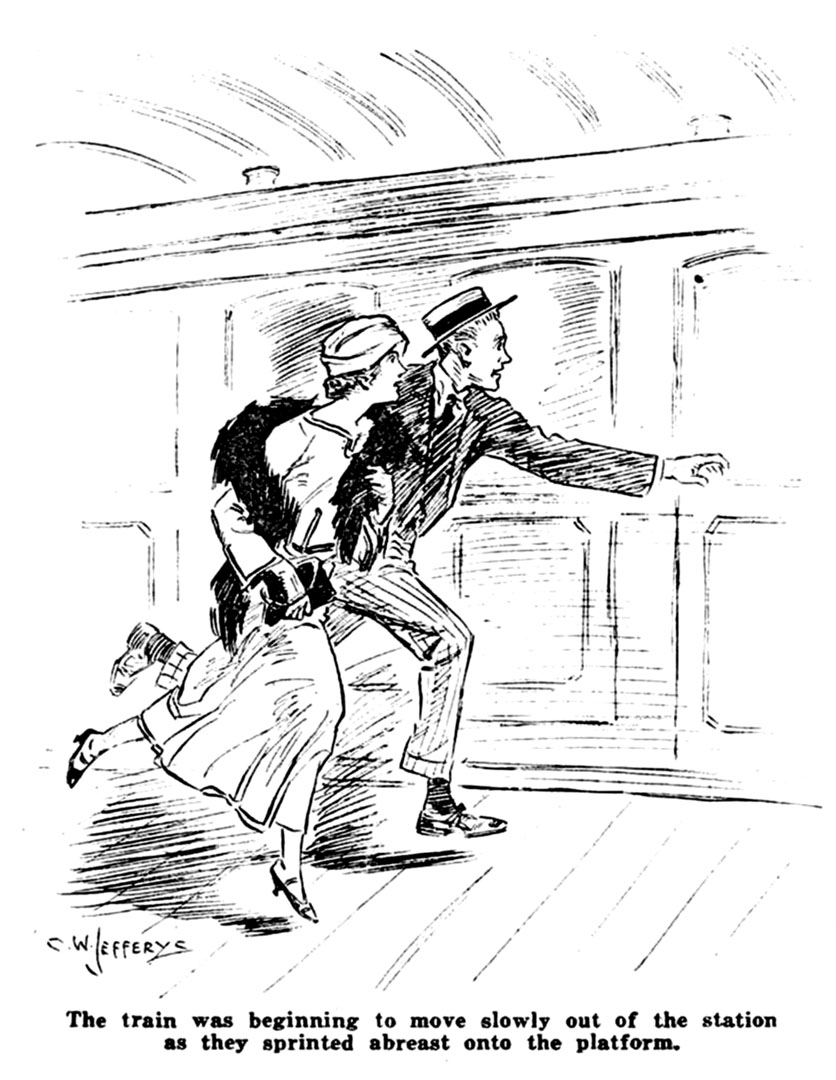

Ginger, alert after his unexpected fashion when it became a question of physical action, had followed her through the swing door, and they emerged together and started running down the Square.

“Stick it!” said Ginger encouragingly. He was running easily and well, as becomes a man who in his day has been a snip for his international as scrum half.

Sally saved her breath. The train was beginning to move slowly out of the station as they sprinted abreast on to the platform. Ginger dived for the nearest door, wrenched it open, gathered Sally neatly in his arms, and flung her in. She landed squarely on the toes of a man who occupied the corner seat, and, bounding off again, made for the window. Ginger, faithful to the last, was trotting beside the train as it gathered speed.

Sally saved her breath. The train was beginning to move slowly out of the station as they sprinted abreast on to the platform. Ginger dived for the nearest door, wrenched it open, gathered Sally neatly in his arms, and flung her in. She landed squarely on the toes of a man who occupied the corner seat, and, bounding off again, made for the window. Ginger, faithful to the last, was trotting beside the train as it gathered speed.

“Ginger! My poor porter! Tip him! I forgot.”

“Right-ho!”

“And don’t forget what I’ve been saying.”

“Right-ho!”

“Look after yourself and—Death to the Family!”

“Right-ho!”

The train passed smoothly out of the station. Sally cast one last look back at her red-haired friend, who had now halted, and was waving a handkerchief. Then she turned to apologize to the other occupant of the carriage.

“I’m so sorry,” she said breathlessly. “I hope I didn’t hurt you.”

She found herself facing Ginger’s cousin, the dark man of yesterday’s episode on the beach, Bruce Carmyle. . . .

MR. CARMYLE was not a man who readily allowed himself to be disturbed by life’s little surprises, but at the present moment he could not help feeling slightly dazed. He recognized Sally now as the French girl who had attracted his cousin Lancelot’s notice on the beach. At least, he had assumed that she was French, and it was startling to be addressed by her now in fluent English. How had she suddenly acquired this gift of tongues? And how on earth had she had time since yesterday when he had been a total stranger to her, to become sufficiently intimate with Cousin Lancelot to be sprinting with him down station platforms and addressing him out of railway-carriage windows as Ginger? Bruce Carmyle was aware that most members of that subspecies of humanity, his cousin’s personal friends, called him by that familiar—and, so Carmyle held, vulgar—nickname, but how had this girl got hold of it?

If Sally had been less pretty, Mr. Carmyle would undoubtedly have looked disapprovingly at her, for she had given his rather rigid sense of the proprieties a nasty jar. But as, panting and flushed from her run, she was prettier than any girl he had yet met, he contrived to smile.

“Not at all,” he said in answer to her question, though it was far from the truth. His left big toe was aching confoundedly. Even a girl with a foot as small as Sally’s can make her presence felt on a man’s toe if the scrum half who is handling her aims well and uses plenty of vigor.

“If you don’t mind,” said Sally, sitting down, “I think I’ll breathe a little.”

She breathed. The train sped on.

“Quite a close thing,” said Bruce Carmyle affably. The pain in his toe was diminishing. “You nearly missed it.”

“Yes. It was lucky Mr. Kemp was with me. He throws very straight, doesn’t he?”

“Tell me,” said Carmyle, “how do you come to know my cousin? On the beach yesterday morning—”

“Oh, we didn’t know each other then. But we were staying at the same hotel, and we spent an hour or so shut up in an elevator together. That was when we really got acquainted.”

A waiter entered the compartment, announcing in unexpected English that dinner was served in the restaurant car.

“Would you care for dinner?”

“I’m starving,” said Sally.

She reproved herself, as they made their way down the corridor, for being so foolish as to judge anyone by his appearance. This man was perfectly pleasant in spite of his grim exterior. She had decided, by the time they had seated themselves at the table, that she liked him.

At the table, however, Mr. Carmyle’s manner changed for the worse. He lost his amiability. He was evidently a man who took his meals seriously and believed in treating waiters with severity. He shuddered austerely at a stain on the tablecloth, and then concentrated himself frowningly on the bill of fare. Sally, meanwhile, was establishing cozy relations with the much-too-friendly waiter, a cheerful old man who from the start seemed to have made up his mind to regard her as a favorite daughter. The waiter talked no English and Sally no French, but they were getting along capitally when Mr. Carmyle, who had been irritably waving aside the servitor’s lighthearted advice—at the Hotel Splendide the waiters never bent over you and breathed cordial suggestions down the side of your face—gave his order crisply in the Anglo-Gallic dialect of the traveling Briton. The waiter remarked “Boum!” in a pleased sort of way and vanished.

“Nice old man!” said Sally.

“Infernally familiar!” said Mr. Carmyle.

SALLY perceived that on the topic of the waiter she and her host did not see eye to eye and that little pleasure or profit could be derived from any discussion centering about him. She changed the subject. She was not liking Mr. Carmyle quite so much as she had done a few minutes ago, but it was courteous of him to give her dinner, and she tried to like him as much as she could. “By the way,” she said, “my name is Nicholas. I always think it’s a good thing to start with names, don’t you?”

“Mine—”

“Oh, I know yours. Ginger—Mr. Kemp told me.”

Mr. Carmyle who since the waiter’s departure had been thawing, stiffened again at the mention of Ginger.

“Indeed?” he said coldly. “Apparently you got intimate.”

Sally did not like his tone. He seemed to be criticizing her, and she resented criticism from a stranger. Her eyes opened wide and she looked dangerously across the table.

“Why ‘apparently’? I told you that we had got intimate, and I explained how. You can’t stay shut up in an elevator half the night with anybody without getting to know him. I found Mr. Kemp very pleasant.”

“Really?”

“And very interesting.”

Mr. Carmyle raised his eyebrows. “Would you call him interesting?”

“I did call him interesting.” Sally was beginning to feel the exhilaration of battle. Men usually made themselves extremely agreeable to her, and she reacted belligerently under the stiff unfriendliness which had come over her companion in the last few minutes. “He told me all about himself.”

“And you found that interesting?”

“Why not?”

“Well. . . .” A frigid half smile came and went on Bruce Carmyle’s dark face. “My cousin has many excellent qualities, no doubt—he used to play football well, and I understand that he is a capable amateur pugilist—but I should not have supposed him entertaining. We find him a little dull.”

“I thought it was only royalty that called themselves ‘we’.”

“I meant myself—and the rest of the family.”

The mention of the Family was too much for Sally. She had to stop talking in order to allow her mind to clear itself of rude thoughts.

“Mr. Kemp was telling me about Mr. Scrymgeour,” she went on at length.

Bruce Carmyle stared for a moment at the yard or so of French bread which the waiter had placed on the table.

“Indeed?” he said. “He has an engaging lack of reticence.”

The waiter returned, bearing soup, and dumped it down.

“V’la!” he observed with the satisfied air of a man who has successfully performed a difficult conjuring trick. He smiled at Sally expectantly, as though confident of applause from this section of his audience at least. But Sally’s face was set and rigid. She had been snubbed, and the sensation was not as pleasant as it was novel.

Snubbed! And by a blue-chinned Englishman! She found herself now disliking Mr. Carmyle with an almost Gingerian intensity. Was it for this that her fathers had bled? Did he suppose that the Spirit of ’76 was in Cain’s Storehouse? If she wanted to talk about Ginger, she was going to talk about Ginger—yes, if the whole British Empire raised its eyebrows.

“I think Mr. Kemp had hard luck.”

“If you will excuse me, I would prefer not to discuss the matter.”

MR. CARMYLE’S attitude was that Sally might be a pretty girl, but she was a stranger, and the intimate affairs of the Family were not to be discussed with strangers, however prepossessing.

“He was quite in the right. Mr. Scrymgeour was beating a dog . . . .”

“I have heard the details.”

“Oh, I didn’t know that. Well, don’t you agree with me then?”

“I do not. A man who would throw away an excellent position simply because—”

“Oh, well, if that’s your view, I suppose it is useless to talk about it.”

“Quite.”

“Still, there’s no harm in asking what you propose to do about Gin—about Mr. Kemp.”

Mr. Carmyle became more glacial. “I’m afraid I cannot discuss—”

Sally’s quick impatience, nobly restrained till now, finally got the better of her. “Oh, for goodness sake!” she snapped. “Do try to be human, and don’t always be snubbing people. You remind me of one of those portraits of men in the eighteenth century, with wooden faces, who look out of heavy gold frames at you with fishy eyes as if you were a regrettable incident.”

“Rosbif,” said the waiter genially, manifesting himself suddenly beside them as if he had popped out of a trap.

“Rosbif,” said the waiter genially, manifesting himself suddenly beside them as if he had popped out of a trap.

Bruce Carmyle attacked his roast beef morosely. Sally, who was in the mood when she knew that she would be ashamed of herself later on, but was full of battle at the moment, sat in silence.

“I am sorry,” said Mr. Carmyle ponderously, “if my eyes are fishy. The fact has not been called to my attention before.”

“I suppose you never had any sisters,” said Sally. “They would have told you.”

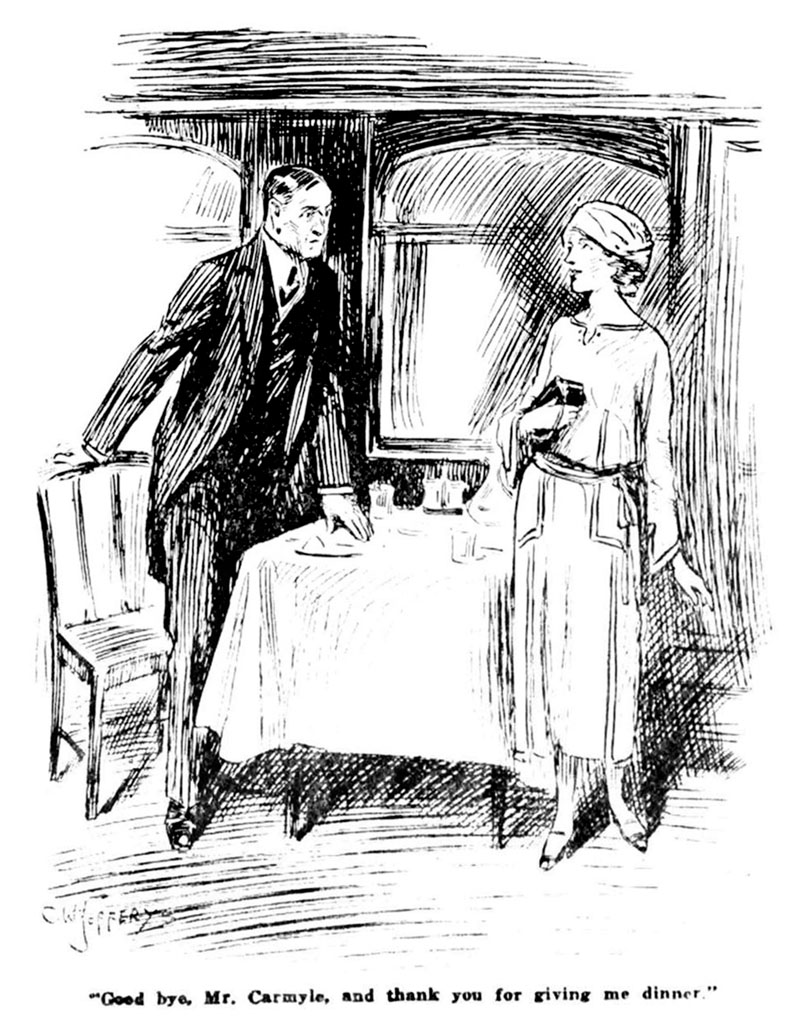

Mr. Carmyle relapsed into an offended dumbness which lasted till the waiter had brought the coffee.

“I think,” said Sally, getting up, “I’ll be going now. I don’t seem to want my coffee, and if I stay on I may say something rude. I thought I might be able to put in a good word for Mr. Kemp and save him from being massacred, but apparently it’s no use. Good-by, Mr. Carmyle and thank you for giving me dinner.”

She made her way down the car, followed by Bruce Carmyle’s indignant, yet fascinated gaze. Strange emotions were stirring in Mr. Carmyle’s bosom.

IV

SOME few days later, owing to the fact that the latter, being preoccupied, did not see him first, Bruce Carmyle met his cousin Lancelot in Piccadilly. They had returned by different routes from Roville, and Ginger would have preferred the separation to continue. He was hurrying on with a nod when Carmyle stopped him.

“Just the man I wanted to see,” he observed.

“Oh, hullo!” said Ginger without joy.

“I was thinking of calling at your club.”

“Yes?”

“Yes. Cigarette?”

Ginger peered at the proffered case with the vague suspicion of the man who has allowed himself to be lured on to the platform and is accepting a card from the conjurer. He felt bewildered. In all the years of their acquaintance he could not recall another such exhibition of geniality on his cousin’s part. He was surprised, indeed, at Mr. Carmyle’s speaking to him at all, for the Affaire Scrymgeour remained an unhealed wound, and the Family, Ginger knew, were even now in session upon it.

“Been back in London long?”

“Day or two.”

“I heard quite by accident that you had returned and that you were staying at the club. By the way, thank you for introducing me to Miss Nicholas.”

Ginger started violently. “What!”

“I was in that compartment, you know, at Roville Station. You threw her right on top of me. We agreed to consider that an introduction. An attractive girl.”

Bruce Carmyle had not entirely made up his mind regarding Sally, but on one point he was clear, that she should not, if he could help it, pass out of his life. Her abrupt departure had left him with that baffled and dissatisfied feeling which, though it has little in common with love at first sight, frequently produces the same effects. She had had, he could not disguise it from himself, the better of their late encounter, and he was conscious of a desire to meet her again and show her that there was more in him than she apparently supposed. Bruce Carmyle, in a word, was piqued; and, though he could not quite decide whether he liked or disliked Sally, he was very sure that a future without her would have an element of flatness.

“A very attractive girl. We had a very pleasant talk.”

“I bet you did,” said Ginger enviously.

“By the way, she did not give you her address by any chance?”

“Why?” said Ginger, suspiciously. His attitude toward Sally’s address resembled somewhat that of a connoisseur who has acquired an unique work of art. He wanted to have it to himself and gloat over it.

“Well, I—er—I promised to send her some books she was anxious to read. . . .”

“I shouldn’t think she gets time for reading.”

“Books which are not published in America.”

“Oh, pretty nearly everything is published in America, what? Bound to be, I mean.”

“Well, these particular books are not,” said Mr. Carmyle shortly. He was finding Ginger’s reserve a little trying, and wished that he had been more inventive.

“Give them to me and I’ll send them to her,” suggested Ginger.

“Good Lord, man!” snapped Mr. Carmyle. “I’m capable of sending a few books to America. Where does she live?”

GINGER revealed the sacred number of the holy street which had the luck to be Sally’s headquarters. He did it because with a persistent devil like his cousin there seemed no way of getting out of it, but he did it grudgingly.

“Thanks.” Bruce Carmyle wrote the information down with a gold pencil in a dapper little morocco-bound notebook. He was the sort of man who always has a pencil, and the backs of old envelopes never entered into his life.

There was a pause. Bruce Carmyle coughed. “I saw Uncle Donald this morning,” he said.

His manner had lost its geniality. There was no need for it now, and he was a man who objected to waste. He spoke coldly, and in his voice there was a familiar sub-tinkle of reproof.

“Yes?” said Ginger moodily. This was the uncle in whose office he had made his début as a hasher—a worthy man, highly respected in the National Liberal Club, but never a favorite of Ginger’s. There were other minor uncles and a few subsidiary aunts who went to make up the family, but Uncle Donald was unquestionably the managing director of that body, and it was Ginger’s considered opinion that in this capacity he approximated to a human blister.

“He wants you to dine with him tonight at Bleke’s.”

Ginger’s depression deepened. A dinner with Uncle Donald would hardly have been a cheery function even in the surroundings of a banquet in the Arabian Nights. There was that about Uncle Donald’s personality which would have cast a sobering influence over the orgies of the Emperor Tiberius at Capri. To dine with him at a morgue like that relic of Old London, Bleke’s Coffee House which confined its custom principally to regular patrons who had not missed an evening there in half a century, was to touch something very near bedrock. Ginger was extremely doubtful whether flesh and blood were equal to it.

“To-night?” he said. “Oh, you mean to-night? Well. . . .”

“Don’t be a fool. You know as well as I do that you’ve got to go.” Uncle Donald’s invitations were royal commands in the Family. “If you’ve another engagement you must put it off.”

“Oh, all right.”

“Seven-thirty sharp.”

“All right,” said Ginger gloomily.

The two men went their ways, Bruce Carmyle eastward because he had clients to see in his chambers at the Temple; Ginger westward because Mr. Carmyle had gone east. There was little sympathy between these cousins; yet, oddly enough, their thoughts as they walked were centered on the same object. Bruce Carmyle, threading his way briskly through the crowds of Piccadilly Circus, was thinking of Sally, and so was Ginger as he loafed aimlessly toward Hyde Park Corner, bumping in a sort of coma from pedestrian to pedestrian.

SINCE his return to London Ginger had been in bad shape. He mooned through the days and slept poorly at night. If there is one thing rottener than another in a pretty blighted world, one thing which gives a fellow the pip and reduces him to the condition of an absolute onion, it is hopeless love. Hopeless love had got Ginger all stirred up. His had been hitherto a placid soul. Even the financial crash which had so altered his life had not bruised him very deeply. His temperament had enabled him to bear the slings and arrows of outrageous fortune with a philosophic “Right-ho!” But now everything seemed different. Things irritated him acutely which before he had accepted as inevitable—his Uncle Donald’s mustache, for instance, and its owner’s habit of employing it during meals as a sort of zareba or earthwork against the assaults of soup.

“By gad!” thought Ginger, stopping suddenly opposite Devonshire House, “if he uses that damned shrubbery as a soup strainer to-night, I’ll slosh him with a fork!”

Hard thoughts . . . . hard thoughts! And getting harder all the time, for nothing grows more quickly than a mood of rebellion. Rebellion is a forest fire that flames across the soul. The spark had been lighted in Ginger, and long before he reached Hyde Park Corner he was ablaze and crackling. By the time he returned to his club he was practically a menace to society—to that section of it, at any rate, which embraced his uncle Donald, his minor uncles George and William, and his aunts Mary, Geraldine, and Louise.

Nor had the mood passed when he began to dress for the dismal festivities of Bleke’s Coffee House. He scowled as he struggled morosely with an obstinate tie. One cannot disguise the fact Ginger was warming up. And it was just at this moment that Fate, as though it had been waiting for the psychological instant, applied the finishing touch. There was a knock at the door, and a waiter came in with a telegram.

Ginger looked at the envelope. It had been readdressed and forwarded on from the Hotel Normandie. It was a wireless, handed in on board the White Star liner Olympic, and it ran as follows:

Remember. Death to the Family. S.

Ginger sat down heavily on the bed.

The driver of the taxicab which at twenty-five minutes past seven drew up at the dingy door of Bleke’s Coffee House in the Strand was rather struck by his fare’s manner and appearance. A determined-looking sort of young bloke, was the taxi-driver’s verdict.

V

IT HAD been Sally’s intention, on arriving in New York, to take a room at the St. Regis and revel in the gilded luxury to which her wealth entitled her before moving into the small but comfortable apartment which, as soon as she had time, she intended to find, and make her permanent abode. But when the moment came and she was giving directions to the taxi-driver at the dock, there seemed to her something revoltingly Fillmorian about the scheme. It would be time enough to sever herself from the boarding house which had been her home for three years when she had found the apartment. Meanwhile, the decent thing to do, if she did not want to brand herself in the sight of her conscience as a female Fillmore, was to go back temporarily to Mrs. Meecher’s admirable establishment and foregather with her old friends. After all, home is where the heart is, even if there are more prunes there than the gourmet would consider judicious.

Perhaps it was the unavoidable complacency induced by the thought that she was doing the right thing, or possibly it was the tingling expectation of meeting Gerald Foster again after all these weeks of separation, that made the familiar streets seem wonderfully bright as she drove through them. It was a perfect crisp New York morning, all blue sky and amber sunshine, and even the ash cans had a stimulating look about them. The street cars were full of happy people rollicking off to work, policemen directed the traffic with jaunty affability, and the white-clad street cleaners went about their poetic tasks with a quiet but none the less noticeable relish. It was improbable that any of these people knew that she was back, but somehow they all seemed to be behaving as though this were a special day.

The first discordant note in this overture of happiness was struck by Mrs. Meecher, who informed Sally, after expressing her gratification at the news that she required her old room, that Gerald Foster had left town that morning.

“Gone to Detroit he has,” said Mrs. Meecher. “Miss Doland too.” She broke off to speak a caustic word to the boarding-house handy man who, with Sally’s trunk as a weapon, was depreciating the value of the wall paper in the hall. “There’s that play of his being tried out there, you know, Monday,” resumed Mrs. Meecher, after the handy man had bumped his way up the staircase. “They been rehearsing ever since you left.”

SALLY was disappointed. New York was so wonderful after the dull voyage in the liner that she was not going to allow herself to be depressed without good reason. After all, she could go on to Detroit to-morrow. It was nice to have something to which she could look forward.

“Oh, is Elsa in the company?” she said.

“Sure. And very good too.” Mrs. Meecher was an ex-member of the profession, having been in the first production of “Florodora,” though, unlike everybody else, not one of the original Sextette. “Mr. Faucitt was down to see a rehearsal, and he said Miss Doland was fine. And he’s not easy to please, as you know.”

”How is Mr. Faucitt?”

Mrs. Meecher, not unwillingly, for she was a woman who enjoyed the tragedies of life, made her second essay in the direction of lowering Sally’s uplifted mood.

“Poor old gentleman, he ain’t over and above well. Went to bed early last night with a headache, and this morning I been to see him and he don’t look well. There’s a lot of this Spanish influenza about. It might be that. Lots o’ people been dying of it, if you believe what you see in the papers,” said Mrs. Meecher buoyantly.

“Good gracious! You don’t think—”

“Well, he ain’t turned black,” admitted Mrs. Meecher with regret. “They say they turn black. If you believe what you see in the papers, that is. Of course that may come later,” she added with the air of one confident that all will come right in the future. “The doctor’ll be in to see him pretty soon. He’s quite happy. Toto’s sitting with him.”

“I must go up and see him,” cried Sally. “Poor old dear!”

“Sure. You know his room. You can hear Toto talking to him now,” said Mrs. Meecher complacently. “He wants a cracker, that’s what he wants. Toto likes a cracker after breakfast.”

THE invalid’s eyes, as Sally entered the room, turned wearily to the door.

“Sally!”

“I’ve only just arrived in my hired barouche from the pier.”

“And you came to see your old friend without delay? I am grateful and flattered, Sally, my dear.”

“Of course I came to see you. Do you suppose that, when Mrs. Meecher told me you were sick, I just said ‘Is that so?’ and went on talking about the weather? Well, what do you mean by it? Frightening everybody. Poor old darling, do you feel very had?”

“One thousand individual mice are nibbling the base of my spine, and I am conscious of a constant need of cooling refreshment. But what of that? Your presence is a tonic. Tell me, how did our Sally enjoy foreign travel?”

“Our Sally had the time of her life.”

“Did you visit England?”

“Only passing through.”

“How did it look?” asked Mr. Faucitt eagerly.

“Moist. Very moist.”

“It would.” said Mr. Faucitt, indulgently. “l confess that, happy as I have been in this country, there are times when I miss those wonderful London days when a sort of cozy brown mist hangs over the streets and the pavements ooze with a perspiration of mud and water, and you see through the haze the yellow glow of the Bodega lamps shining in the distance like harbor lights. Not,” said Mr. Faucitt, “that I specify the Bodega to the exclusion of other and equally worthy hostelries. I have passed just as pleasant hours in Rule’s and Short’s. You missed something by not lingering in England, Sally.”

“I know I did—pneumonia.”

MR. FAUCITT shook his head reproachfully. “You are prejudiced, my dear. You would have enjoyed London if you had had the courage to brave its superficial gloom. Where did you spend your holiday? Paris?”

“Part of the time. And the rest of the while I was down by the sea. It was glorious. I don’t think I would ever have come back if I hadn’t had to. But, of course, I wanted to see you all again. And I wanted to be at the opening of Mr. Foster’s play. Mrs. Meecher tells me you went to one of the rehearsals.”

“I attended a dog fight which I was informed was a rehearsal,” said Mr. Faucitt severely. “There is no rehearsing nowadays.”

“Oh, dear! Was it as bad as all that?”

“The play is good. The play—I will go further—is excellent. It has fat. But the acting! . . . .”

“Mrs. Meecher said you told her that Elsa was good.”

“Our worthy hostess did not misreport me. Miss Doland has great possibilities. She reminds me somewhat of Matilda Devine, under whose banner I played a season at the old Royalty in London many years ago. She has the seeds of greatness in her, but she is wasted in the present case on an insignificant part. There is only one part in the play. I allude to the one murdered by Miss Mabel Hobson.”

“Murdered!” Sally’s heart sank. She had been afraid of this, and it was no satisfaction to feel that she had warned Gerald. “Is she very terrible?”

“She has the face of an angel and the histrionic ability of that curious suet pudding which our estimable Mrs. Meecher is apt to give us on Fridays.”

“Oh, poor Ger—poor Mr. Foster!”

“I do not share your commiseration for that young man,” said Mr. Faucitt austerely. “You probably are almost a stranger to him, but he and I have been thrown together a good deal of late. A young man upon whom, mark my words, success, if it ever comes, will have the worst effects. I dislike him, Sally. He is, I think, without exception the most selfish and self-centered young man of my acquaintance. He reminds me very much of old Billy Fothergill, with whom I toured a good deal in the later eighties. Did I ever tell you the story of Billy and the amateur who—”

Sally was in no mood to listen to the adventure of Mr. Fothergill. The old man’s innocent criticism of Gerald had stabbed her deeply. A momentary impulse to speak hotly in his defense died away as she saw Mr. Faucitt’s pale, worn old face. He had meant no harm, after all. How could he know what Gerald was to her?

SHE changed the conversation abruptly. “Have you seen anything of Fillmore while I’ve been away?”

“Fillmore? Why yes, my dear, curiously enough I happened to run into him on Broadway only a few days ago. He seemed changed--less stiff and aloof than he had been for some time past. I may be wronging him, but there have been times of late when one might almost have fancied him a trifle upstage. All that was gone at our last encounter. He appeared glad to see me and was most cordial.”

Sally found her composure restored. Her lecture on the night of the party had evidently, she thought, not been wasted. Mr. Faucitt, however, advanced another theory to account for the change in the Man of Destiny.

“I rather fancy,” he said, “that the softening influence has been the young man’s fiancée.”

“What! Fillmore’s not engaged?”

“Did he not write and tell you? I suppose he was waiting to inform you when you returned. Yes, Fillmore is betrothed. The lady was with him when we met. A Miss Winch. In the profession, I understand. He introduced me. A very charming and sensible young lady I thought.”

Sally shook her head. “She can’t be. Fillmore would never have got engaged to anyone like that. Was her hair crimson?”

“Brown, if I recollect rightly.”

“Very loud, I suppose, and over-dressed?”

“On the contrary, neat and quiet.”

“You’ve made a mistake,” said Sally decidedly. “She can’t have been like that. I shall have to look into this. It does seem hard that I can’t go away for a few weeks without all my friends taking to beds of sickness and all my brothers getting ensnared by vampires.”

IT WAS not till the following Friday that Sally was able to start for Detroit. She arrived on the Saturday morning and drove to the Hotel Statler. Having ascertained that Gerald was stopping in the hotel and having phoned up to his room to tell him to join her, she went into the dining room and ordered breakfast.

She was pouring out her second cup of coffee when a stout young man of whom she had caught a glimpse as he moved about that section of the hotel lobby which was visible through the open door of the dining room, came in and stood peering about as though in search of someone. The momentary sight she had had of this young man had interested Sally. She had thought how extraordinarily like he was to her brother Fillmore. Now she perceived that it was Fillmore himself.

“Why, Sally!” His manner, she thought, was nervous—one might almost have said embarrassed. She attributed this to a guilty conscience. Presently he would have to break to her the news that he had become engaged to be married without her sisterly sanction, and no doubt he was wondering how to begin. “What are you doing here? I thought you were in Europe.”

“I got back a week ago, but I’ve been nursing poor old Mr. Faucitt ever since then. He’s been ill, poor old dear. I’ve come here to see Mr. Foster’s play. ‘The Primrose Way,’ you know. Is it a success?”

“It hasn’t opened yet.”

“Don’t be silly, Fill. Do pull yourself together. It opened last Monday.”

“No, it didn’t. Haven’t you heard? They’ve closed all the theatres because of this infernal Spanish influenza. Nothing has been playing this week. You must have seen it in the papers.”

“I haven’t had time to read the papers. Oh, Fill, what an awful shame!”

“Yes, it’s pretty tough. Makes the company all on edge. I’ve had the darndest time, I can tell you.”

“Why, what have you got to do with it?”

FILLMORE coughed. “I—er—oh, I didn’t tell you that. I’m sort of—er—mixed up in the show. Cracknell—you remember he was at college with me—suggested that I should come down and look at it. I shouldn’t wonder if he wants me to put money into it, and so on.”

“I thought he had all the money in the world.”

“Yes, he has a lot, but these fellows like to let a pal in on a good thing.”

“Is it a good thing?”

“The play’s fine.”

“That’s what Mr. Faucitt said. But Mabel Hobson!. . . .”

Fillmore’s ample face registered emotion.

“She’s an awful woman, Sally! She can’t act, and she throws her weight about all the time. The other day there was a fuss about a paper knife—”

“How do you mean, a fuss about a paper knife?”

“One of the props, you know. It got mislaid. I’m certain it wasn’t my fault—”

“How could it have been your fault?” asked Sally wonderingly. Love seemed to have had the worst effect on Fillmore’s mentality.

“Well—er—you know how it is. Angry woman—blames the first person she sees. . . . This paper knife . . . .”

Fillmore’s voice trailed off into pained silence.

“Mr. Faucitt said Elsa Doland was good.”

“Oh, she’s all right,” said Fillmore indifferently. “But”—his face brightened and animation crept into his voice—“but the girl you want to watch is Miss Winch. Gladys Winch. She plays the maid! She’s only on in the first act, and hasn’t much to say except ‘Did you ring, madam?’ and things like that. But it’s the way she says ’em. Sally, that girl’s a genius! The greatest character actress in a dozen years! You mark my words, in a darned little while you’ll see her name up on Broadway in electric lights. Personality? Ask me! Charm? She wrote the words and music! Looks?”

“All right! All right! I know all about it, Fill. And will you kindly inform me how you dared to get engaged without consulting me?”

Fillmore blushed richly. “Oh, do you know?”

“Yes. Mr. Faucitt told me.”

“Well—”

“Well?”

“Well, I’m only human,” argued Fillmore.

“I call that a very handsome admission. You’ve got quite modest, Fill.”

He had certainly changed for the better since their last meeting. It was as if some one had punctured him and let out all the pomposity. If this was due, as Mr. Faucitt had suggested, to the influence of Miss Winch, Sally felt she could not but approve of the romance.

“I’ll introduce you some time,” said Fillmore.

“I want to meet her very much.”

“I’ll have to be going now. I’ve got to see Bunbury. I thought he might be in here.”

“Who’s Bunbury?”

“The producer. I suppose he’s breakfasting in his room. I’d better go up.”

“You are busy, aren’t you! Little marvel! It’s lucky they’ve got you to look after them!”

FILLMORE retired, and Sally settled down to wait for Gerald, no longer hurt by his manner over the telephone. Poor Gerald! No wonder he had seemed upset.

A few minutes later he came in.

“Oh, Jerry darling,” said Sally, as he reached the table. “I’m so sorry. I’ve just been hearing about it.”

Gerald did not seem interested either by the news of Mr. Faucitt’s illness or by the fact that Sally, after delay, had at last arrived. He dug a spoon somberly into his grape-fruit.

“We’ve been hanging about here day after day, getting bored to death all the time. The company’s going all to pieces. They’re sick of rehearsing and rehearsing when nobody knows if we’ll ever open. They were all keyed up a week ago, and they’ve been sagging ever since. It will ruin the play, of course. My first chance! Just chucked away.”

Sally was listening with a growing feeling of desolation. She tried to be fair, to remember that he had had a terrible disappointment and was under a great strain. And yet—it was unfortunate that self-pity was a thing she particularly disliked in a man. Her vanity, too, was hurt. It was obvious that her arrival, so far from acting as a magic restorative, had effected nothing. She could not help remembering, though it made her feel disloyal, what Mr. Faucitt had said about Gerald. She had never noticed before that he was remarkably self-centered, but he was thrusting the fact upon her attention now.

“That Hobson woman is beginning to make trouble,” went on Gerald, prodding in a despairing sort of way at scrambled eggs. “She ought never to have had the part; never. She can’t handle it. Elsa Doland could play it a thousand times better. I wrote Elsa in a few lines the other day, and the Hobson went right up in the air. You don’t know what a star is till you’ve seen one of these promoted clothes props from the Follies trying to be one. It took me an hour to talk her round and keep her from throwing up her part.”

“Why not let her throw up her part?”

“For Heaven’s sake talk sense,” said Gerald querulously. “Do you suppose that man Cracknell would keep the play on if she wasn’t in it? He would close the show in a second, and where would I be then? You don’t seem to realize that this is a big chance for me. I’d look a fool throwing it away.”

“I SEE,” said Sally shortly. She had never felt so wretched in her life.

“By the way,” said Gerald, “there’s one thing. I have to keep jollying her along all the time, so for goodness’ sake don’t go letting it out that we’re engaged.”

Sally’s chin went up with a jerk. This was too much. “If you find it a handicap being engaged to me—”

“Don’t be silly.” Gerald took refuge in pathos. “Good God! It’s tough! Here am I, worried to death and you—”

“I know, I know. But you never told me you were glad to see me.”

“Of course I’m glad to see you.”

“Why didn’t you say so, then, you poor fish? And why didn’t you ask me if I had enjoyed myself in Europe?”

“Did you enjoy yourself?”

“Yes, except that I missed you so much. There! Now we can consider my lecture on foreign travel finished, and you can go on telling me your troubles.”

Gerald accepted the invitation. He spoke at considerable length, though with little variety. It appeared definitely established in his mind that Providence had invented Spanish influenza purely with a view to wrecking his future. But now he seemed less aloof, more open to sympathy. The brief thunderstorm had cleared the air. Sally lost that sense of detachment and exclusion which had weighed upon her.

“Well,” said Gerald at length, looking at his watch, “I suppose I had better be off.”

“Rehearsal?”

“Yes, confound it. It’s the only way of getting through the day. Are you coming along?”

“I’ll come directly I’ve unpacked and tidied myself up.”

“See you at the theatre, then.”

Sally went out and rang for the elevator to take her to her room. . . .

THE rehearsal had started when she reached the theatre. On the stage Elsa Doland, looking very attractive, was playing a scene with a man in a derby hat. She was speaking a line as Sally came in:

“Why, what do you mean, father?”

“Tiddly-omty-om,” was the derby-hatted one’s surprising reply. “Tiddly-omty-om; . . . long speech ending in ‘find me in the library.’ And exit,” said the man in the derby hat, starting to do so.

For the first time Sally became aware of the atmosphere of nerves. Mr. Bunbury, who seemed to be a man of temperament, picked up his walking stick, which was leaning against the next seat, and flung it with some violence across the house. “For God’s sake!” said Mr. Bunbury.

“Now what?” inquired the derby hat, interested, pausing halfway across the stage.

“Do speak the lines, Teddy,” exclaimed Gerald. “Don’t skip them in that sloppy way.”

“You don’t want me to go over the whole thing?” asked the derby hat amazed.

“Yes!”

“Not the whole d——— thing?” queried the derby hat, fighting with incredulity.

“This is a rehearsal!” snapped Mr. Bunbury. “If we are not going to do it properly, what’s the use of doing it at all?”

This seemed to strike the erring Teddy, if not as reasonable, at any rate as one way of looking at it. He delivered the speech in an injured tone and shuffled off. The atmosphere of tenseness was unmistakable now. Sally could feel it.

Elsa Doland now moved to the door, pressed a bell, and, taking a magazine from the table, sat down in a chair near the footlights. A moment later, in answer to the ring, a young woman entered, to be greeted instantly by an impassioned bellow from Mr. Bunbury: “Miss Winch!”

THE new arrival stopped and looked out over the footlights.

“Hello!” said Miss Winch amiably.

Mr. Bunbury was profoundly moved. “Miss Winch, did I or did I not ask you to refrain from chewing gum during rehearsal?”

“That’s right. So you did,” admitted Miss Winch chummily.

‘Then why are you doing it?”

“SHALL I say my big speech now?” inquired Miss Winch over the footlights.

“Yes, yes! Get on with the rehearsal. We’ve wasted half the morning.”

“Did you ring, madam?” said Miss Winch to Elsa, who had been reading her magazine placidly through the late scene.

The rehearsal proceeded, and Sally watched it with a sinking heart. It was all wrong. Novice as she was in things theatrical, she could see that.

A shrill, passionate cry from the front row, and Mr. Bunbury was on his feet again. Sally could not help wondering whether things were going particularly wrong to-day or whether this was one of Mr. Bunbury’s ordinary mornings.

“Miss Hobson!”

“Oh, gee!” said Miss Hobson, ceasing to be the distressed wife and becoming the offended star. “What’s it this time?”

“I suggested at the last rehearsal, and at the rehearsal before that and the rehearsal before that, that on that line you should pick up the paper knife and toy negligently with it. You did it yesterday, and to-day you’ve forgotten it again.”

“My God!” cried Miss Hobson, wounded to the quick. “If this don’t beat everything! How the heck can I toy negligently with a paper knife when there’s no paper knife for me to toy negligently with?”

“The paper knife is on the desk.”

“It’s not on the desk.”

“No paper knife?”

“No paper knife. And it’s no good picking on me. I’m the star, not the assistant stage manager. If you’re going to pick on anybody, pick on him.”

The advice appeared to strike Mr. Bunbury as good. He threw back his head and bayed like a bloodhound.

There was a momentary pause, and then from the wings on the prompt side there shambled out a stout and shrinking figure, in whose hand was a script of the play and on whose face, lit up by the footlights, there shone a look of apprehension. It was Fillmore, the Man of Destiny. . . .

ALAS, poor Fillmore! He stood in the middle of the stage with the lightning of Mr. Bunbury’s wrath playing about his defenseless head, and Sally, recovering from her first astonishment, sent a wave of sisterly commiseration floating across the theatre to him.

And as she listened to the fervid eloquence of Mr. Bunbury, she perceived that she had every reason to be. Fillmore was having a bad time.

“I assure you, Mr. Bunbury,” bleated the unhappy Fillmore obsequiously, “I placed it with the rest of the properties after the last rehearsal.”

“You couldn’t have done.”

“I assure you I did.”

“And it walked away, I suppose,” said Miss Hobson with cold scorn, pausing in the operation of brightening up her lower lip with a lip stick.

A calm, clear voice spoke. “It was taken away,” said the calm, clear voice. Miss Winch had added herself to the symposium. She stood beside Fillmore, chewing placidly. It took more than raised voices and gesticulating hands to disturb Miss Winch. “Miss Hobson took it,” she went on in her cozy, drawling voice. “I saw her.”

SENSATION in court. The prisoner, who seemed to feel his position deeply cast a pop-eyed glance full of gratitude at his advocate. Mr. Bunbury, in his capacity of prosecuting attorney, ran his fingers through his hair in some embarrassment, for he was regretting now that he had made such a fuss. Miss Hobson, thus assailed by an underling, spun around and dropped the lip stick, which was neatly retrieved by the assiduous Mr. Cracknell. Mr. Cracknell had his limitations, but he was rather good at picking up lip sticks.

“What’s this? I took it? I never did anything of the sort.”

“Miss Hobson took it after the rehearsal yesterday,” drawled Gladys Winch, addressing the world in general, “and threw it negligently at the theatre cat.”

Miss Hobson seemed taken aback. Her composure was not restored by Mr. Bunbury’s next remark.

“In future, Miss Hobson, I should be glad if, when you wish to throw anything at the cat, you would not select a missile from the property box. Good Heavens!’’ he cried, stung by the way fate was maltreating him, “I have never experienced anything like this before. I have been producing plays all my life, and this is the first time this has happened. I have produced Nazimova. Nazimova never threw paper knives at cats.”

“Well, I hate cats,” said Miss Hobson as though that settled it.

“I,” murmured Miss Winch, “love little pussy; her fur is so warm, and if I don’t hurt her she’ll do me no—’’

“Oh, my heavens!” shouted Gerald Foster, bounding from his seat and for the first time taking a share in the debate. “Are we going to spend the whole day arguing about cats and paper knives? For goodness’ sake, clear the stage and stop wasting time.”

Miss Hobson chose to regard this intervention as an affront. “Don’t shout at me, Mr. Foster!”

“I wasn’t shouting at you.”

“If you have anything to say to me, lower your voice.”

“He can’t,” observed Miss Winch. “He’s a tenor.”

“Nazimova never—’’ began Mr. Bunbury.

Miss Hobson was not to be diverted from her theme by reminiscences of Nazimova. She had not finished dealing with Gerald. “In the shows I’ve been in,” she said mordantly, “the author wasn’t allowed to go about the place getting fresh with the leading lady. In the shows I’ve been in the author sat at the back and spoke when he was spoken to. In the shows I’ve been in—’’

SALLY was tingling all over. This reminded her of the dog fight on the Roville sands. She wanted to be in it, and only the recognition that it was a private fight, and that she would be intruding, kept her silent. The lure of the fray, however, was too strong for her wholly to resist it. Almost unconsciously she had risen from her place and drifted down the aisle so as to be nearer the white-hot center of things. She was now standing in the lighted space by the orchestra pit, and her presence attracted the roving attention of Miss Hobson who, having concluded her remarks on authors and their legitimate sphere of activity, was looking about for some other object of attack.

“Who the devil,” inquired Miss Hobson, “is that?”

Sally found herself an object of universal scrutiny, and wished that she had remained in the obscurity of the back rows. “I am Mr. Nicholas’s sister,” was the best method of identification that she could find.

“Who’s Mr. Nicholas?”

“I’m through!” announced Miss Hobson. It appeared that Sally’s presence had in some mysterious fashion fulfilled the function of the last straw.

“Hello, Sally,” said Elsa Doland, looking up from her magazine. The battle, raging all round her, had failed to disturb her detachment. “When did you get back?”

Sally trotted up the steps which had been propped against the stage to form a bridge over the orchestra pit.

“Hello, Elsa.”

The late debaters had split into groups. Mr. Bunbury and Gerald were pacing up and down the central aisle, talking earnestly. Fillmore had subsided onto a chair.

“Do you know Gladys Winch?” asked Elsa.

Sally shook hands with the placid lodestar of her brother’s affections. Miss Winch on closer inspection proved to have deep gray eyes and freckles. Sally’s liking for her increased.

“Thank you for saving Fillmore from the wolves,” she said. “They would have torn him in pieces but for you.”

“Oh, I don’t know,” said Miss Winch.

“It was noble.”

“Oh, well!”

“I think,” said Sally, “I’ll go and have a talk with Fillmore. He looks as though he wanted consoling.”

She made her way to that picturesque ruin.

To be Continued

Notes:

Printer’s errors corrected above:

Magazine had “She owelcmed the chance”; corrected to “welcomed”

Magazine had “really amount to something?”; corrected to end with a period as in books

Magazine omitted the query between “independent of them” and the ellipsis dots, and put an extra query after “conundrums”

Magazine omitted the comma in “Ginger, alert”

Magazine had “cer way down the har”; corrected

Magazine had “dingy door of the Bleke’s Coffee House”; “the” omitted as in books

Magazine omitted closing quote after “And very good too.”

Magazine had “he said Miss Donald was fine”; amended to “Doland”

Magazine had “All that was done at our last encounter”; corrected to “gone” as in other versions.

Magazine had “that sense of detachment, and exclusion”; comma removed to make sense, and as in books

Madame Eulalie’s Rare Plums

Madame Eulalie’s Rare Plums