Pearson’s (UK), June 1909

Illustrated by R. Noel Pocock

I.

My family are a great anxiety to me. Sometimes when Saunders is doing my hair—it’s been up for ages—nearly six months—I look in the glass, and wonder why it’s not grey—the hair, I mean.

There is my brother Bob, for instance. He’s much better, now, of course, for I have worked very hard at him; but when he first went to Oxford he was dreadful. He required the very firmest treatment on my part.

And even father, when my eye is not on him. . . . There was that business of the right-of-way for example.

It happened the summer before I put my hair up. I had been away for a visit to Aunt Flora. She is one of my muddling aunts, not nearly so nice as Aunt Edith, but, on the other hand, not perfectly awful like Aunt Elizabeth. I was glad to get back.

The motor was waiting for me at the station. I sat in front instead of in the tonneau, because I wanted to talk to Phillipps, the chauffeur. He always tells me what has been happening while I have been away, and what the butler thinks about it.

To-day he started about old Joe Gossett. Joe is an old man who earns a little by winding up some of the big clocks in the village—the church clock, the one over the stables at home, and one or two more. At least, he’s supposed to; but he often forgets, and then the clocks stop, and there’s rather a fuss. I like Joe. He is a friend of mine. We have long talks about pigs. He loves talking about pigs. He has two of his own, and they are like sons to him. I have known him talk for three-quarters of an hour about them.

“Old Joe,” said Phillipps, “he forgot to wind up the stable clock again. He’s careless, miss.”

I said: “Poor Joe! Was father cross?”

Phillipps chuckled. He is the only chauffeur I have met who ever does chuckle.

“Ah!” he said. “You’re right, miss. Told him off to rights, the colonel did, miss. Old Joe, he’s always talking about his blessed pigs, till he forgets there’s anything except them in the world.” Phillipps let the car go a mile before he said anything else. He’s like that. He turns himself off like a tap.

He started again quite suddenly.

“Rare excitement in the village, miss, about that there right-of-way.”

That was the first I had heard of it. Phillipps told me the story in jerks.

It was like this. I am condensing Phillipps’ explanation, and leaving out what he said to the butler about it, and what the butler said to him.

Beyond the wood at the end of our lake is a field. The villagers have always used it as a short cut. It saved them going round two sides of a big triangle. Father didn’t mind. They never went off the path, but simply walked straight from gate to gate. They had been doing it as long as I could remember. Well, father, after letting them do it for years, has suddenly said they mustn’t, and closed the field. And now there was great excitement, because the villagers said that they had a legal right to use the path, and father said no, they hadn’t anything of the sort, and that he had a perfect right to stop them.

I couldn’t understand it a bit, because father had always been so nice to the villagers, and there didn’t seem any reason for suddenly being horrid to them.

Then Phillipps explained further, and I understood.

“Mr. Morris,” he said—Morris is our butler—“says that it’s not, rightly speaking, the colonel’s doing at all. Mr. Morris says it was Mr. Rastrick as put him up to it, and made him do it. Mr. Morris says he heard him at it while he was pouring out the sherry at dinner. Mr. Morris says Mr. Rastrick kept on telling the colonel he was being put upon, and must stand up for his rights, and about the thin edge of the wedge. Mr. Morris says that what’s set the colonel off.”

Then I saw the whole thing, because I knew Mr. Rastrick, and knew just how he would talk father over. I hate Mr. Rastrick. He was at school with father, and sometimes comes to stay with us. He has a private school near London. My brother Bob says he bears him no grudge for that, but that what he objects to is that Mr. Rastrick seems to look on our house as a sort of branch of his private school. He is one of those horrid men who will try to manage everybody’s business. I have heard him telling Morris how to look after a cellar. He sometimes lectures Phillipps on motors. And he was always giving me advice in a horrid managing way when he was last stopping with us.

I could see him persuading father. My brother Bob once said to me that, if you were tactful, father would let you sit on his lap and help yourself out of his pockets; but that, if he got the idea that he was being let in on the quiet, he ramped.

Evidently he had ramped about this right-of-way business.

I made up my mind that I would try and stop it if I possibly could, because I know that in a day or two, when he had had time to think it over quietly, he would wish that he hadn’t done it, only he would be too proud to give in then.

I thought a great deal about it as I dressed for dinner.

* * * * *

When I got down to the dining-room, I found father and Mr. Rastrick there, and Mr. Rastrick’s son, Augustus. He looked about fifteen. I had never seen him before.

“You know Joan,” said father.

“Whoop-oop-oop,” said Mr. Rastrick. “How you have grown! Quite the little woman, Romney, eh?”

Father beamed. I felt like scratching. I hate men who talk like aunts.

I said: “How do you do, Mr. Rastrick?” in a cold voice I usually keep for horrid boys, who forget that I have grown up, and call me by my Christian name because we used to play tennis together in some prehistoric age. It usually goes right through the boys like an east wind; but Mr. Rastrick didn’t seem to notice it. He leaned against the mantelpiece and went on telling father what he ought to put on the croquet lawn in winter.

Mr. Rastrick was a tall man, with large penetrating grey eyes and a pointed black beard. He was of what they call commanding aspect. I always thought he looked like those old photographs you see in albums, where the father of the family is shown holding a scroll in one hand, apparently just about to address the multitude. Mr. Rastrick always looked as if he were just about to address the multitude. His son Augustus was short and fat. He looked to me a furtive boy. From the time I first saw him to the end of dinner he did not utter a single word, but just pounded away at his food, as if that was all he was there for. He was a little pig of a boy. Saunders, my maid, told me when he had gone that he had spent most of his visit in or near the kitchen, trying to get the cook to give him buns.

Still, it didn’t matter, his being silent. His father made up for it. Between them, they talked just enough for two.

Mr. Rastrick finished off the croquet lawn before the bell rang. He took a short rest during the soup. When the fish came he started on cricket.

“Whoop-oop-oop,” he began—I forgot to say he had a sort of impediment in his speech. When once he was fairly started, he talked at a tremendous rate; but he always began his speeches with those three words. It was just like a motor goes before it glides off. It was just as if somebody had started his engines.

“The young fellows nowadays,” said Mr. Rastrick, beginning to glide off, “have no notion of what I call real cricket. Put them on a billiard-table, and they can play forward all day. What I like to see is the man who can make runs on a good old-fashioned village pitch. Your Frys, and Haywards, and Palairets, where would they be on a village green? What about their three thousand runs in a season then? Why I tell you my boy Gussie would bowl them all out in a twinkling.”

Gussie, who had been stuffing himself with salmon, looked round the table with his mouth full in a sort of hunted way, and remained silent.

“My boy Gussie,” Mr. Rastrick went on with pride, “is a capital bowler—capital. I have trained him myself. I didn’t let him bowl fast, like so many stupid boys. I said to him: ‘Gussie, if I catch you trying to plug them in,’ as I believe the expression is, ‘I’ll thrash you!’ And I’d have done it, too.”

Gussie looked sad and thoughtful, as though he were brooding over painful memories.

“Whoop-oop-oop,” said Mr. Rastrick enthusiastically. “Playing for my school last term against the Charchester College third eleven, an exceedingly powerful combination, including the cousin of an Oxford blue, my boy Gussie scored seven wickets for forty-six runs.”

“No, did he, upon my word?” said father. “We must get up a village match for you to play in, Augustus. Seven for forty-six! By George! Excellent!”

“Whoop-oop-oop, including the cousin of an Oxford blue,” said Mr. Rastrick.

“Splendid!”

The gorging boy gnawed his second helping of salmon without uttering.

It was just then that I had my idea. Do you ever notice how, when you have been thinking very hard about something, and can’t decide on anything, it sometimes comes to you suddenly when you aren’t thinking about it? It was just like that now. I had been trying all the time I was dressing to find some way of settling this quarrel between father and the village, and I couldn’t think of anything. And now it came to me all of a sudden.

I said: “Father, I’ve thought of a splendid way of settling the right-of-way thing. Of course, I know they haven’t any business in the field really. Still, you’ve always let them go through it.”

“Who told you about it?” asked father.

I said Phillipps had. I said: “Why not get up a match to decide it, father? It would be awful fun. If they win, let them have the right-of-way. And if we win, you could do what you liked, and shut up the field. I wish you would. Don’t you think it’s a good idea, father?” Because, you see, I thought the village were certain to win. Father used to be a splendid bat, and is still very good; but I didn’t think we had anyone much except him, Bob being away on a cricket tour with the Authentics; and some of the village team bat very well.

I know Mr. Rastrick was just opening his mouth to say “Whoop-oop-oop, preposterous!” but it was too late. Father always likes anything sporting, and I could see he loved this idea.

“Excellent! Capital!” he cried. “A splendid idea. I don’t want to be hard on these fellows. It doesn’t matter to me whether they go through the field or not. It’s only the principle of the thing. I’ll arrange it tonight.”

“Whoop-oop-oop,” began Mr. Rastrick disapprovingly; but father’s mind was made up.

“Now let me see,” he said. “About our team.”

II.

I must say that the House team was what Bob would have called a pretty scratch lot. Mr. Rastrick kept talking about his boy Gussie, and what he would do when he was put face to face with the village batsmen; but I thought he would have to be very good to make up for the rest. There were two grooms, three gardeners, John (the footman), Phillipps (who, Saunders told me, bowled very fast) and the curate, Mr. Travers. He was a new curate, quite different from our last one, who had once or twice played for his county. Mr. Travers had been twelfth man in his House eleven at school, he told me, but that was long ago.

I thought that the village would win easily.

Our village matches at Much Middlefold are played on a meadow close to the churchyard. It is not a very nice ground—for cricket, that is to say. There is a mown space in the middle about the size of a tennis-lawn. All around it is long grass. The mown space always looks to me like a bit of ground that has been reclaimed from the jungle. The turf is not very good. It is rather rough. In a way it is a bad ground for batsmen; but then it is not very nice for the fieldsmen. There are a lot of ditches, some of them quite deep, and the long grass hides these, so that you sometimes see men running for a catch suddenly vanish. Of course, most of our regular village players have got to know where the ditches are, but they are rather a bore to strangers. Sometimes there is wet mud at the bottom of the ditches, and that makes it worse. When there isn’t a match, cows are allowed onto the ground, though nobody really likes their being there; and they make a good many holes. Altogether, it is not a very good ground.

Father won the toss. And after that Mr. Rastrick seemed to appoint himself captain.

“Whoop-oop-oop,” he said, “we bat first, Romney. Most certainly we bat first. You and I will be the first pair. Give the side confidence. After us anybody you like. My boy Gussie second wicket. It is his invariable place.”

I scored. I generally score in our village matches. It was rather strange to-day, for the villagers, instead of crowding round, as they always do, went and sat by themselves, poor dears, at the other side of the field. I suppose they looked on me as one of the enemy. Though, of course, I was really their good angel. I was rather lonely. The curate was the only one of our team who sat by me, and he’s rather a bore. Phillipps, and the grooms, and the gardeners, and John (the footman) were sitting with the maids some way off. They were all giggling and enjoying themselves tremendously.

Just before the game began, old Joe Gossett came stumping along. I hoped he was going to sit by me, but he caught sight of Mr. Travers and stumped off again. Saunders had told me that he had forgotten to wind the church clock last week, and it had stopped and everybody was late for church, and Mr. Travers had been cross with Joe. So I suppose Joe was not anxious to see much of Mr. Travers for a little.

Of course, Mr. Rastrick took first ball. He ought to have let father take it. Father is a very good bat. Mr. Rastrick made a great fuss about taking centre, and looking round to where the fieldsmen were, and he was rather unpleasant to Harris, who always umpires in our village matches. I could not make out what it was all about, but they both waved their hands rather. Then Mr. Rastrick got settled at last, and got ready to play the first ball. And it was rather funny, because it hit him on the elbow (so he said afterwards again and again) and Hunt, the grocer, who was fielding short slip, caught it.

Everybody appealed, including the spectators, and Harris put up his hand as if he was that photograph of the Pope Blessing the World.

Mr. Rastrick had been writhing about so much that he didn’t notice anything till he got ready to take the next ball—and then he saw Harris’ hand. It was quite an age before they could get him to go out. He took off his pads, and went away to a corner of the field by himself, and the curate went in; so now I was left absolutely alone.

The curate was bowled by the last ball of the over, but he did not come back to talk to me. He went away by himself, like Mr. Rastrick, to a corner of the field. It is very queer about cricket. After they get out, men seem to like to go away and brood. At some of our matches I have seen half the team, dotted at intervals round the field, all brooding hard.

We had now got two wickets down for no runs. But it was father’s turn to take the bowling, and he begun to hit at once. He made six off his first over. Three twos. Father nearly always hits along the ground, so he never makes much more than a two when he plays on the village field.

The bowler who had got Mr. Rastrick and Mr. Travers out was Simms, the blacksmith. He is very fast. He sent our men out one after the other. The Gussie child went in after the curate, but he didn’t do anything. He started running away to leg before Simms bowled (though when the ball really came it was quite slow, for Simms wouldn’t bowl his fastest to a boy) and the ball hit the middle stump full pitch. Then Phillipps came in, and after making a tremendous swipe, which went right out of the ground, was caught at square leg by Payne, the baker and confectioner. I don’t believe he noticed Payne was there. Payne was a very little man, and he was standing almost up to his waist in some bushes.

After that nobody did anything hardly, except father, who played splendidly whenever he could get the bowling. The three gardeners were bowled one after the other by Simms; and if John, the footman, who went in last, hadn’t had tremendous luck, and managed to stay in while father made his runs, we should have been out for about twenty. As it was, the last wicket put on eighteen before John was bowled. So our score managed to get up to forty, of which father had made twenty-three not out. There were five byes.

Of course, I thought that now it was all right, because forty was not much to expect the village to make. They often make nearly a hundred. But I had forgotten the Gussie child, or rather, I hadn’t exactly forgotten him, but I didn’t think he could really bowl at all. He could, though. I don’t know if he was really good, but at any rate his was not the sort of bowling the village had been used to and they couldn’t play it at all. Everybody in our village matches bowls either fast or very fast, so they don’t mind fast bowling. They played Phillipps quite easily. But the Gussie child sent in very slow, high-pitched ones, and they swiped desperately at them, poor things, without getting anywhere near them. It would have been funny, only I was so sorry. Simms hit him into the churchyard once, but that was the only time anybody made anything off him. Simms ran himself out, and the rest just swiped, and were either clean bowled or stumped, with yells of triumph, by Mr. Rastrick. The innings was over in half-an-hour for seventeen runs. The little brute Gussie took eight wickets for six.

The only thing was, there was heaps of time for a second innings. So we went in again.

It was dreadfully slow this time. Generally in our village matches everybody hits very hard, but our second innings was not a bit like that. Mr. Rastrick evidently meant to do better this innings. He simply stuck in, and didn’t try to hit. Father got out quite early, caught in the slips. So did Gussie, who had gone in first wicket this time because the curate, who hadn’t expected father to get out so soon, had not got his pads on. Then Mr. Travers and Mr. Rastrick made a stand. It was too dull for anything. When five o’clock struck from the church clock, I got father to look after the scoring, while I went for a walk.

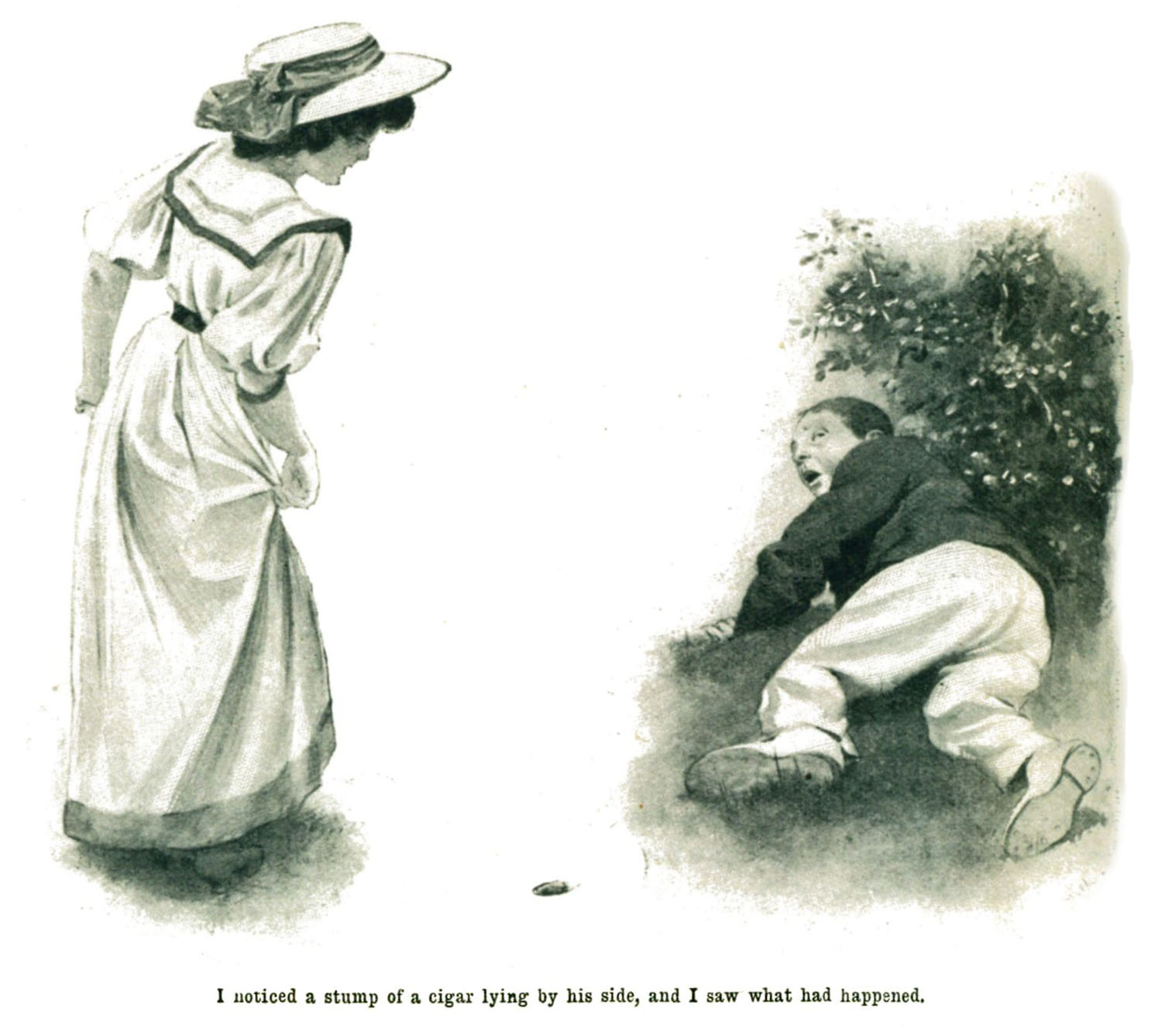

I was on my way to the house to get some tea, feeling perfectly parched, and was taking the short cut across the next field, when I suddenly thought I heard a sort of groan. And then I saw a pair of white boots sticking out from behind a bush.

I went to look.

It was the Gussie child. He was lying on the ground with his head buried in his arms, groaning hollowly. I thought he must have some Secret Sorrow. I thought he was crying.

I said: “Hullo!”

He rolled over, and stared up at me in a horrid, glazed way. He wasn’t crying. His face was all a sort of greeny-yellow.

I said: “What’s the matter?”

He groaned, and rolled over again.

Then I noticed a stump of cigar lying by his side, and I saw what had happened. I picked up the cigar. It was thick and black. I recognized what it was. The same thing had happened to Bob years ago. The cigar was one of a specially strong brand which father gives to the tenants at the tenants’ dinner. He says the farmers like something with a bit of a bite in it. It looked as if Gussie had gotten bitten badly.

I didn’t quite know what to do. Then I thought that he would probably sooner be left alone, so I pulled him by the shoulders till his legs didn’t stick out beyond the bush, so that nobody who happened to pass should see him; and went on to the house and made myself some tea in the kitchen.

When I got back, it was twenty to six, and our side was just out. Mr. Rastrick was strutting about very pleased with himself. I looked at the score-book, and found that he had carried his bat through the innings for twenty-nine. The full score was fifty-seven, which meant the villagers would have to make eighty-one to win in an hour and a quarter. I noticed one or two of them standing about, looking rather sorry for themselves.

“Whoop-oop-oop,” said Mr. Rastrick. “Let’s get out into the field. Play the game. The village must have their second innings. Come along, come along. Where’s my boy Gussie?”

Nobody seemed to have seen him. Everybody began to shout “Gussie!”

I stepped forward. “He’s rather ill,” I said. “I don’t think he’ll be able to bowl this innings.” The faces of the village batsmen who were standing near brightened. They crowded round to listen. “Whoop-oop-oop! Why? What? Ill? What’s the matter with him?”

I didn’t want to get him in trouble. I said: “He may have had a touch of the sun. He’s lying down.” That was true, anyhow.

“Well, never mind,” said father. “I’m sorry he’s seedy. It has been a deuced hot day. He ought to have worn a sun hat instead of that cap. Was he quite comfortable and all right when you left him, Joan?”

I said: “He didn’t seem to want to move, father.”

“He’s keeping quite quiet and out of the sun?”

“Yes, father.”

“Then he’s sure to be all right. These things pass off. We must be getting out into the field, Rastrick. Travers, will you bowl at the churchyard end?”

I saw Simms, the blacksmith, grin furtively, and I knew what he was thinking. I had seen Mr. Travers bowl sometimes at the practice net which they put up in the evenings when work is over.

“What’s the time?” said father.

I looked at my watch.

“Just a quarter to six,” I said.

“Whoop-oop-oop,” said Mr. Rastrick authoritatively. “Now we must have no chivalry, Romney, or any of that nonsense. No playing after time’s up. This is going to be a close thing. We have lost our best bowler, and they are going to try hard for the runs. There must be no playing of extra time. The rigour of the game.”

“We always play by the church clock, sir,” put in Simms. “We go by its strike.”

“Whoop-oop-oop, quite right. Then the moment that the church clock strikes seven, off go the bails; and unless you have knocked off the runs, we win on the first innings. Umpires, do you understand that clearly? We play until the clock strikes seven, and not one instant longer.”

“Right, sir,” said Simms. “Ready, Teddy?”

“E-eh,” said Teddy, who was the village postman. And they went in. I took the scoring-book again.

We started badly, for Mr. Rastrick, standing a long way back to Phillipps’ bowling and backing with his eyes in the air to catch a skier, stepped into a deep ditch just as the ball was dropping. They ran three before he could get out again. There is a good deal of what they call the glorious uncertainty of cricket on our village ground.

After that Simms and the postman seemed to get more encouraged than ever. They hit out splendidly. I must say the bowling was awfully bad. Phillipps was all right at first, but they really liked fast bowling, and after the second over began to hit him all over the place. Mr. Travers, after four very expensive overs, was taken off, and one of the gardeners went on. He started with what I should think must have been the widest wide ever seen on a cricket field. It nearly hit Mr. Travers, who was fielding point. After that he bowled two more wides, and then at last a straight one, which Simms hit into the road.

I could see that we were not going to get the village out again. The only question was whether they could score quick enough to make the runs by seven o’clock. At half past six Simms and the postman were still in, and the score was thirty-six.

I couldn’t see the clock, so I had to go by my watch, which was five minutes slow. The church clock was hidden from the field, because it had been put on the side of the tower facing the road. There was just one bit of field from which you could have seen the time, but a big yew-tree in the churchyard prevented you doing even that. So, you see, our village matches were always played by the sound of the clock, not by the sight of it. Not that it mattered much not being able to see the clock. We never had any close finishes. When the side which batted last was out, there was nearly always about three-quarters of an hour to spare.

I didn’t think they could do it. You see, it had been a very hot day, and both the batsmen were beginning to be a little tired, especially Simms, who had bowled through two innings. They began to make runs more slowly. Mr. Travers, who went on instead of Phillipps, bowled a maiden. I shouldn’t think he had ever done such a thing before in his life. And only one run was scored off the next over from John the footman, who had gone on instead of the gardener.

It was just a quarter to by my watch, when I suddenly saw old Joe Gossett stumping towards me. He looked excited. I didn’t much want him. I was afraid he was going to come and talk and I wanted to keep all my attention on the game.

He came up almost trotting.

“Hey, miss,” he called out, “what’s the time?”

I told him. “And my watch is slow,” I said, “so it’s really ten to. I don’t think they’ll manage it. They’ve only made fifty-four.”

Mr. Gossett made a curious noise in his throat.

“That dratted clock hev stopped,” he said, scowling at the church tower. “I should ha’ wounded he up yisterday to rights. I ketched sight of he as I were a-comin’ down the road,” he went on complainingly, “and I says, ‘Surely to goodness,’ I says, ‘it ain’t but twenty minutes past the hower.’ And I says, ‘If I hev’n’t bin and forgot that dratted clock agen,’ I says.”

He was just going through the little gate into the churchyard, near which I was sitting, when I had an idea. My brother Bob often says that girls haven’t any notion of fairness and playing the game. He said it when he came back from his cricket tour at the end of the week, and I told him what I did about this match. But I said the end justified the means. And he said, “That’s just the rotten sort of thing you would say.” But I still think it did, because it would have been an awful shame if the villagers had lost their right-of-way—besides encouraging Mr. Rastrick.

Anyhow, this is what I did.

I said: “Don’t go away, Mr. Gossett. I haven’t had anybody to talk to all the afternoon. And there’s plenty of time to wind up the clock. It’s only eight minutes to, so it won’t be needed for another eight minutes. And nobody can see it from the field, so they won’t know it’s stopped.” (My brother Bob, when I told him this, said, “Great Scott! And there are some people who say that women ought to have votes!”)

Well, he came back; but I could see he wasn’t happy. He was all nervous and jumpy, and kept asking me the time every two seconds.

So I said, “How are your pigs, Mr. Gossett?”

(When I told him that, Bob didn’t utter a word. He just lifted up his head and groaned).

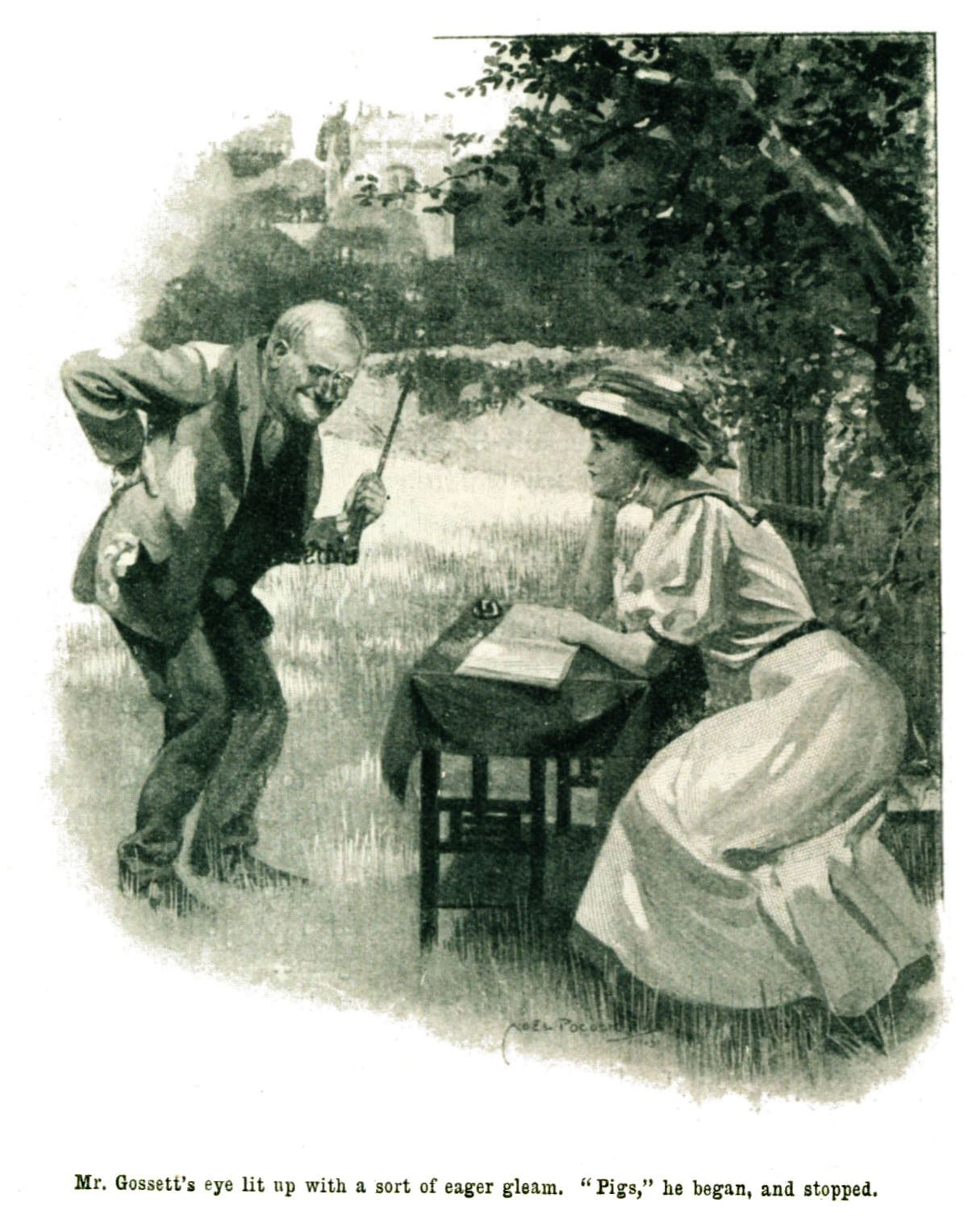

Mr. Gossett’s eye lit up with a sort of eager gleam. He wavered. He looked hesitatingly at the church clock and back again at me.

“Pigs,” he began, and stopped.

“Pigs,” I prompted gently. “I love hearing about your pigs, Mr. Gossett.”

He hesitated no longer. It all came out with a rush. He told me how pigs should be looked after, and how you ought to feed them, and what you should do when they were ill. He talked about pigs he had met. He told me how he had found one of his pigs panting one evening in his sty, and had had to spray its face for a quarter of an hour with cold water. He told me about a fight his two pigs had had. He talked about swine fever, and how to cure it. He said a good lot about bacon, and crackling, and apple-sauce.

It was all awfully interesting.

And all the while Simms and the postman were going on hitting, until, just as Mr. Gossett was beginning to give me some hints on pig-killing, the postman suddenly got out.

I suppose he must have been tired and didn’t see properly, for the ball was a full-pitch, and he ought to have hit it out of the ground. As it was, it bowled him middle stump.

I said, “Oh! He’s out!” and I suppose it sort of broke the spell. Anyway, Mr. Gossett stopped in the middle of a sentence and began to scramble to his feet, muttering about the clock.

I didn’t know what to do. The score was only seventy, and the next man in, who was Payne, the baker, was nowhere near the wicket yet. He had started to run for the crease directly the postman got out, but being so excited, he had not looked where he was going, and he was now scrambling out of the same ditch into which Mr. Rastrick had fallen. He seemed to take hours getting out, and by the time he did, Mr. Gossett was beginning to hobble off to the churchyard gate. I couldn’t stop him. He was so afraid of having it found out he had let the clock run down again that nothing would have made him wait another second.

He disappeared through the gate just as Payne got to the wickets.

Payne really wasn’t the right man to send in at all, considering. He was a little shrimp of a man who just scratched about and hardly ever made a good hard hit. But just because he had gone in first wicket down in the first innings they let him do it now.

There were two more balls of the over to be bowled, and he just patted both of them. And all the time Mr. Gossett was getting nearer and nearer to the clock.

I knew there could only be one more over. As Simms was going to take it, there was just a chance. But I didn’t think he could make as many as eleven.

I have never felt so excited, not even just before I went to my first grown-up dance.

The curate was bowling. Simms swiped at the first ball and missed it. The second ball he hit, but father stopped it. The third he hit very hard, but along the ground, so they only got two, because the grass stopped it. So there were nine more to make and only three balls left.

And then he missed the fourth ball.

“Whoop-oop-oop, well bowled, Travers,” roared Mr. Rastrick, though it wasn’t at all.

But the fifth ball was a full-pitch to leg, and Simms sent it flying to the boundary.

And then, just as the ball had been thrown back and Mr. Travers was going to bowl, the clock struck.

Mr. Rastrick, horrid man, gave a great yell. “Whoop-oop-oop! Off with the bails, umpires! Time’s up!”

And the umpires were just going to do it when father stopped them.

“Nonsense,” he said. “We can’t do that. We must play out the over, of course. One more ball, Simms.”

Simms looked anxious but determined. Mr. Travers looked anxious too. He trotted up to the crease and bowled the last ball. And it was another full-pitch to leg. Only this time, instead of only sending it to the boundary, Simms got really hold of it. It went flying up and up, and fell with a whack right in the middle of the road—a sixer.

“By Jove!” said father, as they reached the scoring-table, “a pretty near thing. How many did Simms make? Fifty-six? Well played, Simms. Capital, capital.” I could see that he was as pleased as anything that the village had won. I knew that he had been thinking things over. “A thoroughly sporting game, Simms. Just tell your fellows that there will be drinks up at the house if they come on there. A wonderfully near thing. You both played splendidly, Simms. I must say, at one time I never thought you’d make the runs.”

I said, “Nor did I, father.”

Editor’s note:

Printer’s errors corrected above:

Magazine had “Quite the little women, Romney, eh?”; corrected to “woman”

Magazine had ‘I know Mr. Rastrick was just opening his month’; corrected to ‘mouth’

Magazine had ‘nobody really likes there being there’; corrected to ‘their being there’

Madame Eulalie’s Rare Plums

Madame Eulalie’s Rare Plums