The Strand Magazine, December 1923

GIVEN private means sufficiently large to pad them against the moulding buffets of Life, it is extraordinary how little men change in after years from the boys they once were. There was a youth in my house at school named Coote. J. G. Coote. And he was popularly known as Looney on account of the vain and foolish superstitions which seemed to rule his every action. Boys are hard-headed, practical persons, and they have small tolerance for the view-point of one who declines to join in a quiet smoke behind the gymnasium not through any moral scruples—which, to do him justice, he would have scorned—but purely on the ground that he had seen a magpie that morning. This was what J. G. Coote did, and it was the first occasion on which I remember him being addressed as Looney.

But, once given, the nickname stuck; and this in spite of the fact—seeing that we were caught half-way through the first cigarette and forcefully dealt with by a muscular head master—that that magpie of his would appear to have known a thing or two. For five happy years, till we parted to go to our respective universities, I never called Coote anything but Looney; and it was as Looney that I greeted him when we happened upon each other one afternoon at Sandown, shortly after the conclusion of the three o’clock race.

“Did you do anything on that one?” I asked, after we had exchanged salutations.

“I went down,” replied Looney, in the subdued but not heart-broken manner of the plutocrat who can afford to do these things. “I had a tenner on My Valet.”

“On My Valet!” I cried, aghast at this inexplicable patronage of an animal which, even in the preliminary saunter round the paddock, had shown symptoms of lethargy and fatigue, not to mention a disposition to trip over his feet. “Whatever made you do that?”

“Yes, I suppose he never had a chance,” agreed Coote, “but a week ago my man Spencer broke his leg, and I thought it might be an omen.”

And then I knew that, for all his moustache and added weight, he was still the old Looney of my boyhood.

“Is that the principle on which you always bet?” I inquired.

“Well, you’d be surprised how often it works. The day my aunt was shut up in the private asylum I collected five hundred quid by backing Crazy Jane for the Jubilee Cup. Have a cigarette?”

“Thanks.”

“Oh, my Lord!”

“Now what?”

“My pocket has been picked,” faltered Looney Coote, withdrawing a trembling hand. “I had a note-case with nearly a hundred quid, and it’s gone!”

The next moment I was astounded to observe a faint, resigned smile on the man’s face.

“Well, that makes two,” he murmured, as if to himself.

“Two what?”

“Two misfortunes. These things always go in threes, you know. Whenever anything rotten happens, I simply brace myself up for the other two things. Well, there’s only one more to come this time, thank goodness.”

“What was the first one?”

“I told you my man Spencer broke his leg.”

“I should have thought that would have ranked as one of Spencer’s three misfortunes. How do you come in?”

“Why, my dear fellow, I’ve been having the devil of a time since he dropped out. The ass they sent me from the agency as a substitute is no good at all. Look at that!” He extended a shapely leg. “Do you call that a crease?”

From the humble standpoint of my own bagginess, I should have called it an excellent crease, but he seemed thoroughly dissatisfied with it, so there was nothing to d0 but tell him to set his teeth and bear it like a man, and presently, the bell having rung for the three-thirty race, we parted.

“Oh, by the way,” said Looney, as he left me, “are you going to be at the Old Wrykinian dinner next week?”

“Yes, I’m coming. So is Ukridge.”

“Ukridge? Good Lord, I haven’t seen old Ukridge for years.”

“Well, he will be there. And I expect he’ll touch you for a temporary loan. That will make your third misfortune.”

Ukridge’s decision to attend the annual dinner of the Old Boys of the school at which he and I had been—in a manner of speaking—educated had come as a surprise to me; for, though the meal was likely to be well-cooked and sustaining, the tickets cost half a sovereign apiece, and it was required of the celebrants that they wear evening-dress. And, while Ukridge sometimes possessed ten shillings which he had acquired by pawning a dress-suit, or a dress-suit which he had hired for ten shillings, it was unusual for him to have the two things together. Still, he was as good as his word, and on the night of the banquet turned up at my lodgings for a preliminary bracer faultlessly clad and ready for the feast.

Tactlessly, perhaps, I asked him what bank he had been robbing.

“I thought you told me a week ago that money was tight,” I said.

“It was tighter,” said Ukridge, “than these damned trousers. Never buy ready-made dress-clothes, Corky, my boy. They’re always unsatisfactory. But all that’s over now. I have turned the corner, old man. Last Saturday we cleaned up to an extraordinary extent at Sandown.”

“We?”

“The firm. I told you I had become a sleeping-partner in a bookie’s business.”

“For Heaven’s sake! You don’t mean to say that it is really making money?”

“Making money? My dear old lad, how could it help making money? I told you from the first the thing was a gold-mine. Affluence stares me in the eyeball. The day before yesterday I bought half-a-dozen shirts. That’ll show you!”

“How much have you made?”

“In some ways,” said Ukridge, sentimentally, “I regret this prosperity. I mean to say, those old careless impecunious days were not so bad. Not so bad, Corky, old boy, eh? Life had a tang then. It was swift, vivid, interesting. And there’s always the danger that one may allow oneself to grow slack and enervated with wealth. Still, it has its compensations. Yes, on the whole I am not sorry to have made my pile.”

“How much have you made?” I asked again, impressed by this time. The fact of Ukridge buying shirts for himself instead of purloining mine suggested an almost Monte Cristo-like opulence.

“Fifteen quid,” said Ukridge. “Fifteen golden sovereigns, my boy! And out of one week’s racing! And you must remember that the thing is going on all the year round. Month by month, week by week, we shall expand, we shall unfold, we shall develop. It wouldn’t be a bad scheme, old man, to drop a judicious word here and there among the lads at this dinner to-night, advising them to lodge their commissions with us. Isaac O’Brien is the name of the firm, 3, Blue Street, St. James’s. Telegraphic address, ‘Ikobee, London,’ and our representative attends all the recognized meetings. But don’t mention my connection with the firm. I don’t want it generally known, as it might impair my social standing. And now, laddie, if we don’t want to be late for this binge, we had better be starting.”

Ukridge, as I have recorded elsewhere, had left school under something of a cloud. Not to put too fine a point on it, he had been expelled for breaking out at night to attend the local fair, and it was only after many years of cold exclusion that he had been admitted to the pure-minded membership of the Old Boys’ Society.

Nevertheless, in the matter of patriotism he yielded to no one.

During our drive to the restaurant where the dinner was to be held he grew more and more sentimental about the dear old school, and by the time the meal was over and the speeches began he was in the mood when men shed tears and invite people, to avoid whom in calmer moments they would duck down side-streets, to go on long walking tours with them. He wandered from table to table with a large cigar in his mouth, now exchanging reminiscences, anon advising contemporaries who had won high positions in the Church to place their bets with Isaac O’Brien of 3, Blue Street, St James’s—a sound and trustworthy firm, telegraphic address “Ikobee, London.”

The speeches at these dinners always opened with a long and statistical harangue from the President, who, furtively consulting his paper of notes, announced the various distinctions gained by Old Boys during the past year. On this occasion, accordingly, he began by mentioning that A. B. Bodger (“Good old Bodger!”—from Ukridge) had been awarded the Mutt-Spivis Gold Medal for Geological Research at Oxford University—that C. D. Codger had been appointed to the sub-junior deanery of Westchester Cathedral—(“That’s the stuff, Codger, old horse!”)—that as a reward for his services in connection with the building of the new waterworks at Strelsau J. J. Swodger had received from the Government of Ruritania the Order of the Silver Trowel, third class (with crossed pickaxes).

“By the way,” said the President, concluding, “before I finish there is one more thing I would like to say. An old boy, B. V. Lawlor, is standing for Parliament next week at Redbridge. If any of you would care to go down and lend him a hand, I know he would be glad of your help.”

He resumed his seat, and the leather-lunged toastmaster behind him emitted a raucous “My Lord, Mr. President, and gentlemen, pray silence for Mr. H. K. Hodger, who will propose the health of ‘The Visitors.’ ” H. K. Hodger rose with the purposeful expression only to be seen on the face of one who has been reminded by the remarks of the last speaker of the story of the two Irishmen; and the company, cosily replete, settled down to give him an indulgent attention.

Not so Ukridge. He was staring emotionally across the table at his old friend Lawlor. The seating arrangements at these dinners were usually designed to bring contemporaries together at the same table, and the future member for Redbridge was one of our platoon.

“Boko, old horse,” demanded Ukridge, “is this true?”

A handsome but rather prominent nose had led his little playmates to bestow this affectionate sobriquet upon the coming M.P. It was one of those boyish handicaps which are never lived down, but I would not have thought of addressing B. V. Lawlor in this fashion myself, for, though he was a man of my own age, the years had made him extremely dignified. Ukridge, however, was above any such weakness. He gave out the offensive word in a vinous bellow of such a calibre as to cause H. K. Hodger to trip over a “begorra” and lose the drift of his story.

“ ’Sh!” said the President, bending a reproving gaze at our table.

“ ’Sh!” said B. V. Lawlor, contorting his smooth face.

“Yes, but is it?” persisted Ukridge.

“Of course it is,” whispered Lawlor. “Be quiet!”

“Then, damme,” shouted Ukridge, “rely on me, young Boko. I shall be at your side. I shall spare no efforts to pull you through. You can count on me to——”

“Really! Please! At that table down there,” said the President, rising, while H. K. Hodger, who had got as far as “Then, faith and begob, it’s me that’ll be afther——” paused in a pained manner and plucked at the table-cloth.

Ukridge subsided. But his offer of assistance was no passing whim, to be lightly forgotten in the slumbers of the night. I was still in bed a few mornings later when he burst in, equipped for travel to the last button and carrying a seedy suit-case.

“Just off, laddie, just off!”

“Fine!” I said. “Good-bye.”

“Corky, my boy,” boomed Ukridge, sitting creakingly on the bed and poisoning the air with his noisome tobacco, “I feel happy this morning. Stimulated. And why? Because I am doing an altruistic action. We busy men of affairs, Corky, are too apt to exclude altruism from our lives. We are too prone to say ‘What is there in it for me?’ and, if there proves on investigation to be nothing in it for us, to give it the miss-in-baulk. That is why this business makes me so confoundedly happy. At considerable expense and inconvenience I am going down to Redbridge to-day, and what is there in it for me? Nothing. Nothing, my boy, except the pure delight of helping an old schoolfellow over a tough spot. If I can do anything, however little, to bring young Boko in at the right end of the poll, that will be enough reward for me. I am going to do my bit, Corky, and it may be that my bit will turn out to be just the trifle that brings home the bacon. I shall go down there and talk——”

“I bet you will.”

“I don’t know much about politics, it’s true, but I can bone up enough to get by. Invective ought to meet the case, and I’m pretty good at invective. I know the sort of thing. You accuse the rival candidate of every low act under the sun, without giving him quite enough to start a libel action on. Now, what I want you to do, Corky, old horse——”

“Oh, heavens!” I moaned at these familiar words.

“——is just to polish up this election song of mine. I sat up half the night writing it, but I can see it limps in spots. You can put it right in half an hour. Polish it up, laddie, and forward without fail to the Bull Hotel, Redbridge, this afternoon. It may just be the means of shoving Boko past the post by a nose.”

He clattered out hurriedly; and, sleep being now impossible, I picked up the sheet of paper he had left and read the verses.

They were well meant, but that let them out. Ukridge was no poet or he never would have attempted to rhyme “Lawlor” with “before us.”

A rather neat phrase happening to occur to me at the breakfast table, coincident with the reflection that possibly Ukridge was right and it did behove his old schoolfellows to rally round the candidate, I spent the morning turning out a new ballad. Having finished this by noon, I dispatched it to the Bull Hotel, and went off to lunch with something of that feeling of satisfaction which, as Ukridge had pointed out, does come to altruists. I was strolling down Piccadilly, enjoying an after-luncheon smoke, when I ran into Looney Coote.

On Looney’s amiable face there was a mingled expression of chagrin and satisfaction.

“It’s happened,” he said.

“What?”

“The third misfortune. I told you it would.”

“What’s the trouble now? Has Spencer broken his other leg?”

“My car has been stolen.”

A decent sympathy would no doubt have become me, but from earliest years I had always found it difficult to resist the temptation to be airy and jocose when dealing with Looney Coote. The man was so indecently rich that he had no right to have troubles.

“Oh, well,” I said, “you can easily get another. Fords cost practically nothing nowadays.”

“It wasn’t a Ford,” bleated Looney, outraged. “It was a brand-new Winchester-Murphy. I paid fifteen hundred pounds for it only a month ago, and now it’s gone.”

“Where did you see it last?”

“I didn’t see it last. My chauffeur brought it round to my rooms this morning, and, instead of staying with it as he should have done till I was ready, went off round the corner for a cup of coffee, so he says! And when he came back it had vanished.”

“The coffee?”

“The car, you ass. The car had disappeared. It had been stolen.”

“I suppose you have notified the police?”

“I’m on my way to Scotland Yard now. It just occurred to me. Have you any idea what the procedure is? It’s the first time I’ve been mixed up with this sort of thing.”

“You give them the number of the car, and they send out word to police-stations all over the country to look out for it.”

“I see,” said Looney Coote, brightening. “That sounds rather promising, what? I mean, it looks as if someone would be bound to spot it sooner or later.”

“Yes,” I said. “Of course, the first thing a thief would do would be to take off the number-plate and substitute a false one.”

“Oh, Great Scott! Not really?”

“And after that he would paint the car a different colour.”

“Oh, I say!”

“Still, the police generally manage to find them in the end. Years hence they will come on it in an old barn with the tonneau stoved in and the engines taken out. Then they will hand it back to you and claim the reward. But, as a matter of fact, what you ought to be praying is that you may never get it back. Then the thing would be a real misfortune. If you get it back as good as new in the next couple of days, it won’t be a misfortune at all, and you will have number three hanging over your head again, just as before. And who knows what that third misfortune may be? In a way, you’re tempting Providence by applying to Scotland Yard.”

“Yes,” said Looney Coote, doubtfully. “All the same, I think I will, don’t you know. I mean to say, after all, a fifteen-hundred-quid Winchester-Murphy is a fifteen-hundred-quid Winchester-Murphy, if you come right down to it, what?”

Showing that even in the most superstitious there may be grains of hard, practical common sense lurking somewhere.

It had not been my intention originally to take any part in the by-election in the Redbridge division beyond writing three verses of a hymn in praise of Boko Lawlor and sending him a congratulatory wire if he won. But two things combined to make me change my mind. The first was the fact that it occurred to me—always the keen young journalist—that there might be a couple of guineas of Interesting Bits money in it (“How a Modern Election is Fought: Humours of the Poll”); the second, that, ever since his departure, Ukridge had been sending me a constant stream of telegrams so stimulating that eventually they lit the spark.

I append specimens:—

“Going strong. Made three speeches yesterday. Election song a sensation. Come on down.—Ukridge.”

“Boko locally regarded as walk-over. Made four speeches yesterday. Election song a breeze. Come on down.—Ukridge.”

“Victory in sight. Spoke practically all yesterday. Election song a riot. Children croon it in cots. Come on down.—Ukridge.”

I leave it to any young author to say whether a man with one solitary political lyric to his credit could have resisted this. With the exception of a single music-hall song (“Mother, She’s Pinching My Leg,” tried out by Tim Sims, the Koy Komic, at the Peebles Hippodrome, and discarded, in response to a popular appeal, after one performance), no written words of mine had ever passed human lips. Naturally, it gave me a certain thrill to imagine the enlightened electorate of Redbridge—at any rate, the right-thinking portion of it—bellowing in its thousands those noble lines:—

“No foreign foe’s insidious hate

Our country shall o’erwhelm

So long as England’s ship of state

Has LAWLOR at the helm.”

Whether I was technically correct in describing as guiding the ship of state a man who would probably spend his entire Parliamentary career in total silence, voting meekly as the Whip directed, I had not stopped to inquire. All I knew was that it sounded well, and I wanted to hear it. In addition to which, there was the opportunity, never likely to occur again, of seeing Ukridge make an ass of himself before a large audience.

I went to Redbridge.

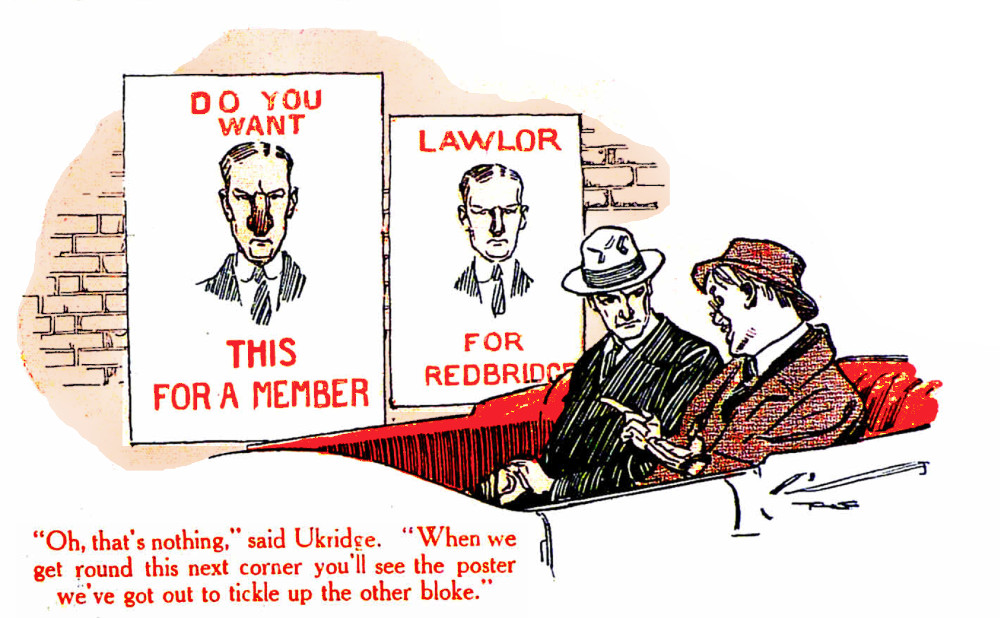

The first thing I saw on leaving the station was a very large poster exhibiting Boko Lawlor’s expressive features, bearing the legend:—

Lawlor

for

Redbridge.

This was all right, but immediately beside it, evidently placed there by the hand of an enemy, was a still larger caricature of this poster which stressed my old friend’s prominent nose in a manner that seemed to me to go beyond the limits of a fair debate. To this was appended the words:—

Do You

Want

THIS

For a Member?

To which, if I had been a hesitating voter of the constituency, I would certainly have replied “No!” for there was something about that grossly elongated nose that convicted the man beyond hope of appeal of every undesirable quality a member of Parliament can possess. You could see at a glance that here was one who, if elected, would do his underhand best to cut down the Navy, tax the poor man’s food, and strike a series of blows at the very root of the home. And, as if this were not enough, a few yards farther on was a placard covering almost the entire side of a house, which said in simple, straightforward black letters a foot high:—

Down With

Boko,

The Human Gargoyle.

How my poor old contemporary, after passing a week in the constant society of these slurs on his personal appearance, could endure to look himself in the face in his shaving-mirror of a morning was more than I could see. I commented on this to Ukridge, who had met me at the station in a luxurious car.

“Oh, that’s nothing,” said Ukridge, huskily. The first thing I had noticed about him was that his vocal cords had been putting in overtime since our last meeting. “Just the usual give-and-take of an election. When we get round this next corner you’ll see the poster we’ve got out to tickle up the other bloke. It’s a pippin.”

I did, and it was indeed a pippin. After one glance at it as we rolled by, I could not but feel that the electors of Redbridge were in an uncommonly awkward position, having to choose between Boko, as exhibited in the street we had just passed, and this horror now before me. Mr. Herbert Huxtable, the opposition candidate, seemed to run as generously to ears as his adversary did to nose, and the artist had not overlooked this feature. Indeed, except for a mean, narrow face with close-set eyes and a murderer’s mouth, Mr. Huxtable appeared to be all ears. They drooped and flapped about him like carpet-bags, and I averted my gaze, appalled.

“Do you mean to say you’re allowed to do this sort of thing?” I asked, incredulously.

“My dear old horse, it’s expected of you. It’s a mere formality. The other side would feel awkward and disappointed if you didn’t.”

“And how did they find out about Lawlor being called Boko?” I inquired, for the point had puzzled me. In a way, you might say that it was the only thing you could possibly call him, but the explanation hardly satisfied me.

“That,” admitted Ukridge, “was largely my fault. I was a bit carried away the first time I addressed the multitude, and I happened to allude to the old chap by his nickname. Of course, the opposition took it up at once. Boko was a little sore about it for a while.”

“I can see how he might be.”

“But that’s all over now,” said Ukridge, buoyantly. “We’re the greatest pals. He relies on me at every turn. Yesterday he admitted to me in so many words that if he gets in it’ll be owing to my help as much as anything. The fact is, laddie, I’ve made rather a hit with the manyheaded. They seem to like to hear me speak.”

“Fond of a laugh, eh?”

“Now, laddie,” said Ukridge, reprovingly, “this is not the right tone. You must curb that spirit of levity while you’re down here. This is a dashed serious business, Corky, old man, and the sooner you realize it the better. If you have come here to gibe and to mock——”

“I came to hear my election song sung. When do they sing it?”

“Oh, practically all the time. Incessantly, you might say.”

“In their baths?”

“Most of the voters here don’t take baths. You’ll gather that when we reach Biscuit Row.”

“What’s Biscuit Row?”

“It’s the quarter of the town where the blokes live who work in Fitch and Weyman’s Biscuit Factory, laddie. It’s what you might call,” said Ukridge, importantly, “the doubtful element of the place. All the rest of the town is nice and clean-cut, they’re either solid for Boko or nuts on Huxtable—but these biscuit blokes are wobbly. That’s why we have to canvass them so carefully.”

“Oh, you’re going canvassing, are you?”

“We are,” corrected Ukridge.

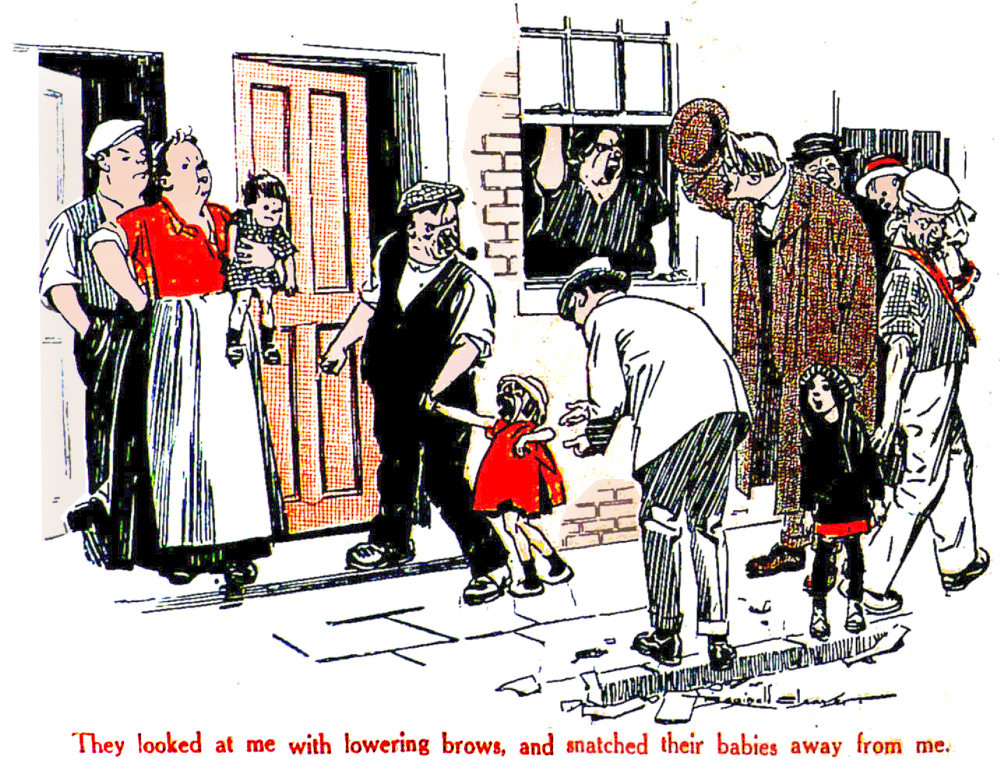

“Not me!”

“Corky,” said Ukridge, firmly, “pull yourself together. It was principally to assist me in canvassing these biscuit blighters that I got you down here. Where’s your patriotism, laddie? Don’t you want old Boko to get into Parliament, or what is it? We must strain every nerve. We must set our hands to the plough. The job you’ve got to tackle is the baby-kissing——”

“I won’t kiss their infernal babies!”

“You will, old horse, unless you mean to spend the rest of your life cursing yourself vainly when it is too late that poor old Boko got pipped on the tape purely on account of your poltroonery. Consider, old man! Have some vision! Be an altruist! It may be that your efforts will prove the deciding factor in this desperately close-run race.”

“What do you mean, desperately close-run race? You said in your wire that it was a walk-over for Boko.”

“That was just to fool the telegraph-bloke, whom I suspect of being in the enemy camp. As a matter of fact, between ourselves, it's touch and go. A trifle either way will do the business now.”

“Why don’t you kiss these beastly babies?”

“There’s something about me that scares ’em, laddie. I’ve tried it once or twice, but only alienated several valuable voters by frightening their offspring into a nervous collapse. I think it’s my glasses they don’t like. But you—now, you,” said Ukridge, with revolting fulsomeness, “are an ideal baby-kisser. The first time I ever saw you, I said: ‘There goes one of Nature’s baby-kissers.’ Directly I started to canvass these people and realized what I was up against, I thought of you. ‘Corky’s the man,’ I said to myself; ‘the fellow we want is old Corky. Good-looking. And not merely good-looking but kind-looking.’ They’ll take to you, laddie. Yours is a face a baby can trust——”

“Now, listen!”

“And it won’t last long. Just a couple of streets and we’re through. So stiffen your backbone, laddie, and go at it like a man. Boko is going to entertain you with a magnificent banquet at his hotel to-night. I happen to know there will be champagne. Keep your mind fixed on that and the thing will seem easy.”

The whole question of canvassing is one which I would like some time to go into at length. I consider it to be an altogether abominable practice. An Englishman’s home is his castle, and it seems to me intolerable that, just as you have got into shirt-sleeves and settled down to a soothing pipe, total strangers should be permitted to force their way in and bother you with their nauseous flattery and their impertinent curiosity as to which way you mean to vote. And, while I prefer not to speak at length of my experiences in Biscuit Row, I must say this much, that practically every resident of that dingy quarter appeared to see eye to eye with me in this matter. I have never encountered a body of men who were consistently less chummy. They looked at me with lowering brows, they answered my limping civilities with gruff monosyllables, they snatched their babies away from me and hid them, yelling, in distant parts of the house. Altogether a most discouraging experience, I should have said, and one which seemed to indicate that, as far as Biscuit Row was concerned, Boko Lawlor would score a blank at the poll.

Ukridge scoffed at this gloomy theory.

“My dear old horse,” he cried, exuberantly, as the door of the last house slammed behind us and I revealed to him the inferences I had drawn, “you mustn’t mind that. It’s just their way. They treat everybody the same. Why, one of Huxtable’s fellows got his hat smashed in at that very house we’ve just left. I consider the outlook highly promising, laddie.”

And so, to my surprise, did the candidate himself. When we had finished dinner that night and were talking over our cigars, while Ukridge slumbered noisily in an easy chair, Boko Lawlor spoke with a husky confidence of his prospects.

“And, curiously enough,” said Boko, endorsing what until then I had looked on as mere idle swank on Ukridge’s part, “the fellow who will have really helped me more than anybody else, if I get in, is old Ukridge. He borders, perhaps, a trifle too closely on the libellous in his speeches, but he certainly has the knack of talking to an audience. In the past week he has made himself quite a prominent figure in Redbridge. In fact, I’m bound to say it has made me a little nervous at times, this prominence of his. I know what an erratic fellow he is, and if he were to become the centre of some horrible scandal it would mean defeat for a certainty.”

“How do you mean, scandal?”

“I sometimes conjure up a dreadful vision,” said Boko Lawlor, with a slight shudder, “of one of his creditors suddenly rising in the audience and denouncing him for not having paid for a pair of trousers or something.”

He cast an apprehensive eye at the sleeping figure.

“You’re all right if he keeps on wearing that suit,” I said, soothingly, “because it happens to be one he sneaked from me. I have been wondering why it was so familiar.”

“Well, anyhow,” said Boko, with determined optimism, “I suppose, if anything like that was going to happen, it would have happened before. He has been addressing meetings all the week, and nothing has occurred. I’m going to let him open the ball at our last rally to-morrow night. He has a way of warming up the audience. You’ll come to that, of course?”

“If I am to see Ukridge warming up an audience, nothing shall keep me away.”

“I’ll see that you get a seat on the platform. It will be the biggest affair we have had. The polling takes place on the next day, and this will be our last chance of swaying the doubters.”

“I didn’t know doubters ever came to these meetings. I thought the audience was always solid for the speakers.”

“It may be so in some constituencies,” said Boko, moodily, “but it certainly isn’t at Redbridge.”

The monster meeting in support of Boko Lawlor’s candidature was held at that popular eyesore, the Associated Mechanics’ Hall. As I sat among the elect on the platform, waiting for the proceedings to commence, there came up to me a mixed scent of dust, clothes, orange-peel, chalk, wood, plaster, pomade, and Associated Mechanics—the whole forming a mixture which, I began to see, was likely to prove too rich for me. I changed my seat in order to bring myself next to a small but promising-looking door, through which it would be possible, if necessary, to withdraw without being noticed.

The principle on which chairmen at these meetings are selected is perhaps too familiar to require recording here at length, but in case some of my readers are not acquainted with the workings of political machines, I may say that no one under the age of eighty-five is eligible and the preference is given to those with adenoids. For Boko Lawlor the authorities had extended themselves and picked a champion of his class. In addition to adenoids, the Right Hon. the Marquess of Cricklewood had—or seemed to have—a potato of the maximum size and hotness in his mouth, and he had learned his elocution in one of those correspondence schools which teach it by mail. I caught his first sentence—that he would only detain us a moment—but for fifteen minutes after that he baffled me completely. That he was still speaking I could tell by the way his Adam’s apple wiggled, but what he was saying I could not even guess. And presently, the door at my side offering its silent invitation, I slid softly through and closed it behind me.

Except for the fact that I was now out of sight of the chairman, I did not seem to have bettered my position greatly. The scenic effects of the hall had not been alluring, but there was nothing much more enlivening to look at here. I found myself in a stone-flagged corridor with walls of an unhealthy green, ending in a flight of stairs. I was just about to proceed towards these in a casual spirit of exploration, when footsteps made themselves heard, and in another moment a helmet loomed into view, followed by a red face, a blue uniform, and large, stout boots—making in all one constable, who proceeded along the corridor towards me with a measured step as if pacing a beat. I thought his face looked stern and disapproving, and attributed it to the fact that I had just lighted a cigarette—presumably in a place where smoking was not encouraged. I dropped the cigarette and placed a guilty heel on it—an action which I regretted the next moment, when the constable himself produced one from the recesses of his tunic and asked me for a match.

“Not allowed to smoke on duty,” he said, affably, “but there’s no harm in a puff.”

I saw now that what I had taken for a stern and disapproving look was merely the official mask. I agreed that no possible harm could come of a puff.

“Meeting started?” inquired the officer, jerking his head towards the door.

“Yes. The chairman was making a few remarks when I came out.”

“Ah! Better give it time to warm up,” he said, cryptically. And there was a restful silence for some minutes, while the scent of a cigarette of small price competed with the other odours of the corridor.

Presently, however, the stillness was interrupted. From the unseen hall came the faint clapping of hands, and then a burst of melody. I started. It was impossible to distinguish the words, but surely there was no mistaking that virile rhythm:—

“Tum tumty tumty tumty tum,

Tum tumty tumty tum,

Tum tumty tumty tumty tum,

Tum TUMTY tumty tum.”

It was! It must be! I glowed all over with modest pride.

“That’s mine,” I said, with attempted nonchalance.

“Ur?” queried the constable, who had fallen into a reverie.

“That thing they’re singing. Mine. My election song.”

It seemed to me that the officer regarded me strangely. It may have been admiration, but it looked more like disappointment and disfavour.

“You on this Lawlor’s side?” he demanded, heavily.

“Yes. I wrote his election song. They’re singing it now.”

“I’m opposed to ’im in toto and root and branch,” said the constable, emphatically. “I don’t like ’is views—subversive, that’s what I call ’em. Subversive.”

There seemed nothing to say to this. This divergence of opinion was unfortunate, but there it was. After all, there was no reason why political differences should have to interfere with what had all the appearance of being the dawning of a beautiful friendship. Pass over it lightly, that was the tactful course. I endeavoured to steer the conversation gently back to less debatable grounds.

“This is my first visit to Redbridge,” I said, chattily.

“Ur?” said the constable, but I could see that he was not interested. He finished his cigarette with three rapid puffs and stamped it out. And as he did so a strange, purposeful tenseness seemed to come over him. His boiled-fish eyes seemed to say that the time of dalliance was now ended and constabulary duty was to be done. “Is that the way to the platform, mister?” he asked, indicating my door with a jerk of the helmet.

I cannot say why it was, but at this moment a sudden foreboding swept over me.

“Why do you want to go on the platform?” I asked, apprehensively.

There was no doubt about the disfavour with which he regarded me now. So frigid was his glance that I backed against the door in some alarm.

“Never you mind,” he said, severely, “why I want to go on that platform. If you really want to know,” he continued, with that slight inconsistency which marks great minds, “I’m goin’ there to arrest a feller.”

It was perhaps a little uncomplimentary to Ukridge that I should so instantly have leaped to the certainty that, if anybody on a platform on which he sat was in danger of arrest, he must be the man. There were at least twenty other earnest supporters of Boko grouped behind the chairman beyond that door, but it never even occurred to me as a possibility that it could be one of these on whom the hand of the law proposed to descend. And a moment later my instinct was proved to be unerring. The singing had ceased, and now a stentorian voice had begun to fill all space. It spoke, was interrupted by a roar of laughter, and began to speak again.

“That’s ’im,” said the constable, briefly.

“There must be some mistake,” I said. “That is my friend, Mr. Ukridge.”

“I don’t know ’is name and I don’t care about ’is name,” said the constable, sternly. “But if ’e’s the big feller with glasses that’s stayin’ at the Bull, that’s the man I’m after. He may be a ’ighly ’umorous and diverting orator,” said the constable, bitterly, as another happy burst of laughter greeted what was presumably a further sally at the expense of the side which enjoyed his support, “but, be that as it may, ’e’s got to come along with me to the station and explain how ’e ’appens to be in possession of a stolen car that there’s been an inquiry sent out from ’eadquarters about.”

My heart turned to water. A light had flashed upon me.

“Car?” I quavered.

“Car,” said the constable.

“Was it a gentleman named Coote who lodged the complaint about his car being stolen? Because——”

“I don’t——”

“Because, if so, there has been a mistake. Mr. Ukridge is a personal friend of Mr. Coote, and——”

“I don’t know whose name it is’s car’s been stolen,” said the constable, elliptically. “All I know is, there’s been an inquiry sent out, and this feller’s got it.”

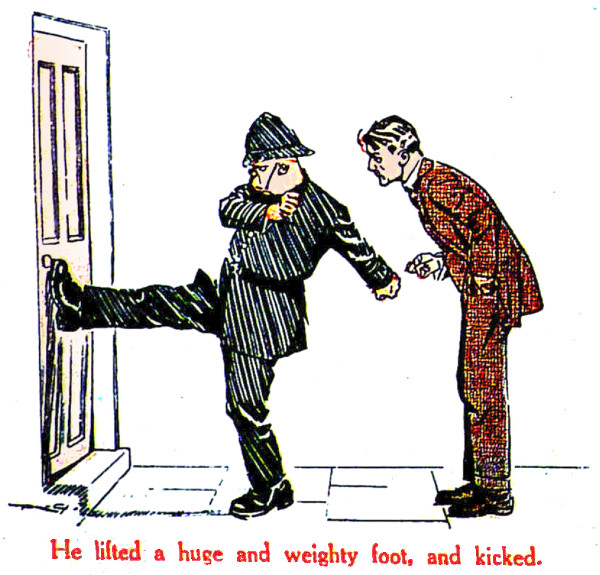

At this point something hard dug into the small of my back as I pressed against the door. I stole a hand round behind me, and my fingers closed upon a key. The policeman was stooping to retrieve a dropped notebook. I turned the key softly and pocketed it.

“If you would kindly not object to standing back a bit and giving a feller a chance to get at that door,” said the policeman, straightening himself. He conducted experiments with the handle. “ ’Ere, it’s locked!”

“Is it?” I said. “Is it?”

“ ’Ow did you get out through this door if it’s locked?”

“It wasn’t locked when I came through.”

He eyed me with dull suspicion for a moment, then knocked imperatively with a large red knuckle.

“Shush! Shush!” came a scandalized whisper through the keyhole.

“Never you mind about ‘Shush! Shush!’ ” said the constable, with asperity. “You open this door, that’s what you do.” And he substituted for the knuckle a leg-of-mutton-like fist. The sound of his banging boomed through the corridor like distant thunder.

“Really, you know,” I protested, “you’re disturbing the meeting.”

“I want to disturb the meeting,” replied this strong but not silent man, casting a cold look over his shoulder. And the next instant, to prove that he was as ready with deeds as with words, he backed a foot or two, lifted a huge and weighty foot, and kicked.

For all ordinary purposes the builder of the Associated Mechanics’ Hall had done his work adequately, but he had never suspected that an emergency might arise which would bring his doors into competition with a policeman’s foot. Any lesser maltreatment the lock might have withstood, but against this it was powerless. With a sharp sound like the cry of one registering a formal protest the door gave way. It swung back, showing a vista of startled faces beyond. Whether or not the noise had reached the audience in the body of the hall I did not know, but it had certainly impressed the little group on the platform. I had a swift glimpse of forms hurrying to the centre of the disturbance, of the chairman gaping like a surprised sheep, of Ukridge glowering; and then the constable blocked out my view as he marched forward over the débris.

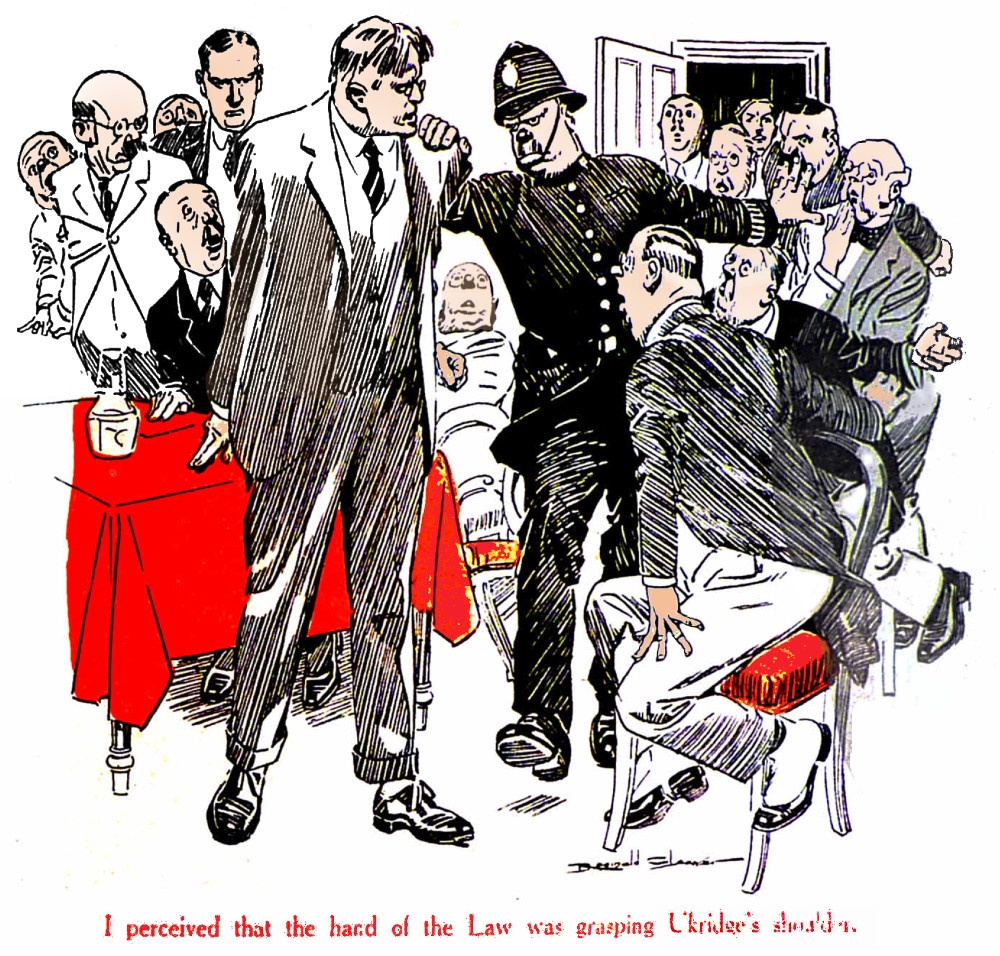

A moment later there was no doubt as to whether the audience was interested. A confused uproar broke out in every corner of the hall, and, hurrying on to the platform, I perceived that the hand of the Law had fallen. It was grasping Ukridge’s shoulder in a weighty grip in the sight of all men.

There was just one instant before the tumult reached its height in which it was possible for the constable to speak with a chance of making himself heard. He seized his opportunity adroitly. He threw back his head and bellowed as if he were giving evidence before a deaf magistrate.

“ ’E’s—stolen—a—mo—tor—car! I’m a-r-resting—’im—for—’avin’—sto—len—a—norter—mobile!” he vociferated in accents audible to all. And then, with the sudden swiftness of one practised in the art of spiriting felons away from the midst of their friends, he was gone, and Ukridge with him.

There followed a long moment of bewildered amazement. Nothing like this had ever happened before at political meetings at Redbridge, and the audience seemed doubtful how to act. The first person to whom intelligence returned was a grim-looking little man in the third row, who had forced himself into prominence during the chairman’s speech with some determined heckling. He bounded out of his chair and stood on it.

“Men of Redbridge!” he shouted.

“Siddown!” roared the audience automatically.

“Men of Redbridge,” repeated the little man, in a voice out of all proportion to his inches, “are you going to trust—do you mean to support—is it your intention to place your affairs in the hands of one who employs criminals——”

“Siddown!” recommended many voices, but there were many others that shouted “ ’Ear, ’Ear!”

“——who employs criminals to speak on his platform? Men of Redbridge, I——”

Here someone grasped the little man’s collar and brought him to the floor. Somebody else hit the collar-grasper over the head with an umbrella. A third party broke the umbrella and smote its owner on the nose. And after that the action may be said to have become general. Everybody seemed to be fighting everybody else, and at the back of the hall a group of serious thinkers, in whom I seemed to recognize the denizens of Biscuit Row, had begun to dismember the chairs and throw them at random. It was when the first rush was made for the platform that the meeting definitely broke up. The chairman headed the stampede for my little door, moving well for a man of his years, and he was closely followed by the rest of the elect. I came somewhere midway in the procession, outstripped by the leaders, but well up in the field. The last I saw of the monster meeting in aid of Boko Lawlor’s candidature was Boko’s drawn and agonized face as he barked his shin on an overturned table in his efforts to reach the exit in three strides.

THE next morning dawned bright and fair, and the sun, as we speeded back to London, smiled graciously in through the windows of our third-class compartment. But it awoke no answering smile on Ukridge’s face. He sat in his corner scowling ponderously out at the green countryside. He seemed in no way thankful that his prison-life was over, and he gave me no formal thanks for the swiftness and intelligence with which I had obtained his release.

A five-shilling telegram to Looney Coote had been the means of effecting this. Shortly after breakfast Ukridge had come to my hotel, a free man, with the information that Looney had wired the police of Redbridge directions to unbar the prison cell. But liberty he appeared to consider a small thing compared with his wrongs, and now he sat in the train, thinking, thinking, thinking.

I was not surprised when his first act on reaching Paddington was to climb into a cab and request the driver to convey him immediately to Looney Coote’s address.

Personally, though I was considerate enough not to say so, I was pro-Coote. If Ukridge wished to go about sneaking his friends’ cars without a word of explanation, it seemed to me that he did so at his own risk. I did not see how Looney Coote could be expected to know by some form of telepathy that his vanished Winchester-Murphy had fallen into the hands of an old schoolfellow. But Ukridge, to judge by his stony stare and tightened lips, not to mention the fact that his collar had jumped off its stud and he had made no attempt to adjust it, thought differently. He sat in the cab, brooding silently, and when we reached our destination and were shown into Looney’s luxurious sitting-room, he gave one long, deep sigh, like that of a fighter who hears the gong go for round one.

Looney fluttered out of the adjoining room in pyjamas and a flowered dressing-gown. He was evidently a late riser.

“Oh, here you are!” he said, pleased. “I say, old man, I’m awfully glad it’s all right.”

“All right!” An overwrought snort escaped Ukridge. His bosom swelled beneath his mackintosh. “All right!”

“I’m frightfully sorry there was any trouble.”

Ukridge struggled for utterance.

“Do you know I spent the night on a beastly plank bed?” he said, huskily.

“No, really? I say!”

“Do you know that this morning I was washed by the authorities?”

“I say, no!”

“And you say it’s all right!”

He had plainly reached the point where he proposed to deliver a lengthy address of a nature calculated to cause alarm and despondency in Looney Coote, for he raised a clenched fist, shook it passionately, and swallowed once or twice. But before he could embark on what would certainly have been an oration worth listening to, his host anticipated him.

“I don’t see that it was my fault,” bleated Looney Coote, voicing my own sentiments.

“You don’t see that it was your fault!” stuttered Ukridge.

“Listen, old man,” I urged, pacifically. “I didn’t like to say so before, because you didn’t seem in the mood for it, but what else could the poor chap have done? You took his car without a word of explanation——”

“What?”

“——and naturally he thought it had been stolen and had word sent out to the police-stations to look out for whoever had got it. As a matter of fact, it was I who advised him to.”

Ukridge was staring bleakly at Looney.

“Without a word of explanation!” he echoed. “What about my letter, the long and carefully-written letter I sent you explaining the whole thing?”

“Letter?”

“Yes!”

“I got no letter,” said Looney Coote.

Ukridge laughed malevolently.

“You’re going to pretend it went wrong in the post, eh? Thin, very thin. I am certain that letter was posted. I remember placing it in my pocket for that purpose. It is not there now, and I have been wearing this suit ever since I left London. See. These are all the contents of my——”

His voice trailed off as he gazed at the envelope in his hand. There was a long silence. Ukridge’s jaw dropped slowly.

“Now, how the deuce did that happen?” he murmured.

I am bound to say that Looney Coote in this difficult moment displayed a nice magnanimity which I could never have shown. He merely nodded sympathetically.

“I’m always doing that sort of thing myself,” he said. “Never can remember to post letters. Well, now that that’s all explained, have a drink, old man, and let’s forget about it.”

The gleam in Ukridge’s eye showed that the invitation was a welcome one, but the battered relics of his conscience kept him from abandoning the subject under discussion as his host had urged.

“But upon my Sam, Looney, old horse,” he stammered, “I—well, dash it, I don’t know what to say. I mean——”

Looney Coote was fumbling in the sideboard for the materials for a friendly carouse.

“Don’t say another word, old man, not another word,” he pleaded. “It’s the sort of thing that might have happened to anyone. And, as a matter of fact, the whole affair has done me a bit of good. Dashed lucky it has turned out for me. You see, it came as a sort of omen. There was an absolute outsider running in the third race at Kempton Park the day after the car went called Stolen Goods, and somehow it seemed to me that the thing had been sent for a purpose. I crammed on thirty quid at twenty-five to one. The people round about laughed when they saw me back this poor, broken-down-looking moke, and, dash it, the animal simply romped home! I collected a parcel!”

We clamoured our congratulations on this happy ending. Ukridge was especially exuberant.

“Yes,” said Looney Coote, “I won seven hundred and fifty quid. Just like that! I put it on with that new fellow you were telling me about at the O. W. dinner, old man—that chap Isaac O’Brien. It sent him absolutely broke and he’s had to go out of business. He’s only paid me six hundred quid so far, but says he has some sort of a sleeping partner or something who may be able to raise the balance.”

(Another story by P. G. Wodehouse next month.)

Notes:

This story first appeared in a slightly different version in the US Cosmopolitan magazine, November 1923, and the present version was collected in Ukridge (Herbert Jenkins, UK, 1924) and He Rather Enjoyed It (Doran, US, 1926). Annotations to the UK book version are elsewhere on this site.

Printer’s error corrected above:

Magazine had “while Ukridge slumbered noisily in an easy chair, Boko Lawler spoke with a husky confidence of his prospects”; corrected to Lawlor.

Madame Eulalie’s Rare Plums

Madame Eulalie’s Rare Plums