The Strand Magazine, January 1925

IN the demeanour of Roland Moresby Attwater, that rising young essayist and literary critic, there appeared, as he stood holding the door open to allow the ladies to leave his uncle Joseph’s dining-room, no outward and visible sign of the irritation that seethed beneath his mud-stained shirt-front. Well-bred and highly civilized, he knew how to wear the mask. The lofty forehead that shone above his rimless pince-nez was smooth and unruffled, and if he bared his teeth it was only in a polite smile. Nevertheless, Roland Attwater was fed to the eyebrows.

In the first place, he hated these family dinners. In the second place, he had been longing all the evening for a chance to explain that muddy shirt, and everybody had treated it with a silent tact which was simply maddening. In the third place, he knew that his uncle Joseph was only waiting for the women to go to bring up once again the infuriating topic of Lucy.

After a preliminary fluttering, not unlike that of hens disturbed in a barnyard, the female members of the party rustled past him in single file—his aunt Emily; his aunt Emily’s friend, Mrs. Hughes-Higham; his aunt Emily’s companion and secretary, Miss Partlett; and his

aunt Emily’s adopted daughter, Lucy. The last-named brought up the rear of the procession. She was a gentle-looking girl with spaniel eyes and freckles, and as she passed she gave Roland a swift, shy glance of admiration and gratitude. It was the sort of look Ariadne might have given Theseus immediately after his turn-up with the Minotaur: and a casual observer, not knowing the facts, would have supposed that, instead of merely opening a door for her, Roland had rescued her at considerable bodily risk from some frightful doom.

After a preliminary fluttering, not unlike that of hens disturbed in a barnyard, the female members of the party rustled past him in single file—his aunt Emily; his aunt Emily’s friend, Mrs. Hughes-Higham; his aunt Emily’s companion and secretary, Miss Partlett; and his

aunt Emily’s adopted daughter, Lucy. The last-named brought up the rear of the procession. She was a gentle-looking girl with spaniel eyes and freckles, and as she passed she gave Roland a swift, shy glance of admiration and gratitude. It was the sort of look Ariadne might have given Theseus immediately after his turn-up with the Minotaur: and a casual observer, not knowing the facts, would have supposed that, instead of merely opening a door for her, Roland had rescued her at considerable bodily risk from some frightful doom.

Roland closed the door and returned to the table. His uncle, having pushed port towards him, coughed significantly and opened fire.

“How did you think Lucy was looking to-night, Roland?”

The young man winced, but the fine courtly spirit which is such a characteristic of the younger members of the intelligentsia did not fail him. Instead of banging the speaker over the head with the decanter, he replied with quiet civility.

“Splendid,” he said.

“Nice girl.”

“Very.”

“Wonderful disposition.”

“Quite.”

“And so sensible.”

“Precisely.”

“Very different from these shingled, cigarette-smoking young women who infest the place nowadays.”

“Decidedly.”

“Had one of ’em up before me this morning,” said Uncle Joseph, frowning austerely over his port. Sir Joseph Moresby was by profession a metropolitan magistrate. “Charged with speeding. That’s their idea of life.”

“Girls,” argued Roland, “will be girls.”

“Not while I’m sitting at Bosher Street police-court, they won’t,” said his uncle, with decision. “Unless they want to pay five-pound fines and have their licenses endorsed.” He sipped thoughtfully. “Look here, Roland,” he said, as one struck by a novel idea, “why the devil don’t you marry Lucy?”

“Well, uncle——”

“You’ve got a bit of money, she’s got a bit of money. Ideal. Besides, you want somebody to look after you.”

“Do you suggest,” inquired Roland, his eyebrows rising coldly, “that I am incapable of looking after myself?”

“Yes, I do. Why, dammit, you can’t even dress for dinner, apparently, without getting mud all over your shirt-front.”

Roland’s cue had been long in coming, but it had arrived at a very acceptable moment.

“If you really want to know how that mud came to be on my shirt-front, Uncle Joseph,” he said, with quiet dignity, “I got it saving a man’s life.”

“Eh? What? How?”

“A man slipped on the pavement as I was passing through Grosvenor Square on my way here. It was raining, you know. And I——”

“You walked here?”

“Yes. And just as I reached the corner of Duke Street——”

“Walked here in the rain? There you are! Lucy would never let you do a foolish thing like that.”

“It began to rain after I had started.”

“Lucy would never have let you start.”

“Are you interested in my story, uncle,” said Roland, stiffly, “or shall we go upstairs?”

“Eh? My dear boy, of course, of course. Most interested. Want to hear the whole thing from beginning to end. You say it was raining and this fellow slipped off the pavement. And then I suppose a car or a taxi or something came along suddenly and you pulled him out of danger. Yes, go on, my boy.”

“How do you mean, go on?” said Roland, morosely. He felt like a public speaker whose chairman has appropriated the cream of his speech and inserted it in his own introductory remarks. “That’s all there is.”

“Well, who was the man? Did he ask you for your name and address?”

“He did.”

“Good! A young fellow once did something very similar to what you did, and the man turned out to be a millionaire and left him his entire fortune. I remember reading about it.”

“In the Family Herald, no doubt?”

“Did your man look like a millionaire?”

“He did not. He looked like what he actually was—the proprietor of a small bird-and-snake shop in Seven Dials.”

“Oh!” said Sir Joseph, a trifle dashed. “Well, I must tell Lucy about this,” he said, brightening. “She will be tremendously excited. Just the sort of thing to appeal to a warm-hearted girl like her. Look here, Roland, why don’t you marry Lucy?”

Roland came to a swift decision. It had not been his intention to lay bare his secret dreams to this pertinacious old blighter, but there seemed no other way of stopping him. He drained a glass of port and spoke crisply.

“Uncle Joseph, I love somebody else.”

“Eh? What’s that? Who?”

“This is, of course, strictly between ourselves.”

“Of course.”

“Her name is Wickham. I expect you know the family? The Hertfordshire Wickhams.”

“Hertfordshire Wickhams!” Sir Joseph snorted, with extraordinary violence. “Bosher Street Wickhams, you mean. If it’s Roberta Wickham, a red-headed hussy who ought to be smacked and sent to bed without her supper, that’s the girl I fined this morning.”

“You fined her!” gasped Roland.

“Five pounds,” said his uncle, complacently. “Wish I could have given her five years. Menace to the public safety. How on earth did you get to know a girl like that?”

“I met her at a dance. I happened to mention that I was a critic of some small standing, and she told me that her mother wrote novels. I chanced to receive one of Lady Wickham’s books for review shortly afterwards, and the—er—favourable tone of my notice apparently gave her some pleasure.” Roland’s voice trembled slightly, and he blushed. Only he knew what it had cost him to write eulogistically of that terrible book. “She has invited me down to Skeldings, their place in Hertfordshire, for the week end to-morrow.”

“Send her a telegram.”

“Saying what?”

“That you can’t go.”

“But I am going.” It is a pretty tough thing if a man of letters who has sold his critical soul is not to receive the reward of his crime. “I wouldn’t miss it for anything.”

“Don’t you be a fool, my boy,” said Sir Joseph. “I’ve known you all your life—know you better than you know yourself—and I tell you it’s sheer insanity for a man like you to dream of marrying a girl like that. Forty miles she was going, right down the middle of Piccadilly. The constable proved it up to the hilt. You’re a quiet, sensible fellow, and you ought to marry a quiet, sensible girl. You’re what I call a rabbit.”

“A rabbit!” cried Roland, stung.

“There is no stigma attached to being a rabbit,” said Sir Joseph, pacifically. “Every man with a grain of sense is one. It simply means that you prefer a normal, wholesome life to gadding about like a—like a non-rabbit. You’re going out of your class, my boy. You’re trying to change your zoological species, and it can’t be done. Half the divorces to-day are due to the fact that rabbits won’t believe they’re rabbits till it’s too late. It is the peculiar nature of the rabbit——”

“I think we had better join the ladies, Uncle Joseph,” said Roland, frostily. “Aunt Emily will be wondering what has become of us.”

IN spite of the innate modesty of all heroes, it was with something closely resembling chagrin that Roland discovered, on going to his club in the morning, that the Press of London was unanimously silent on the subject of his last night’s exploit. Not that one expected anything in the nature of publicity, of course, or even desired it. Still, if there had happened to be some small paragraph under some such title as “Gallant Behaviour of an Author” or “Critical Moment for a Critic,” it would have done no harm to the sale of that little book of thoughtful essays which Blenkinsop’s had just put on the market.

And the fellow had seemed so touchingly grateful at the time.

Pawing at Roland’s chest with muddy hands, he had told him that he would never forget this blinking moment as long as he lived. And he had not bothered even to go and call at a newspaper office.

Well, well! He swallowed his disappointment and a light lunch and returned to his flat, where he found Bryce, his man-servant, completing the packing of his suit-case.

“Packing?” said Roland. “That’s right. Did those socks arrive?”

“Yes, sir.”

“Good!” said Roland. They were some rather special gents’ half-hose from the Burlington Arcade, subtly passionate, and he was hoping much from them. He wandered to the table, and became aware that on it lay a large cardboard box. “Hullo, what’s this?”

“A man left it a short while ago, sir. A somewhat shabbily-dressed person. The note accompanying it is on the mantelpiece, sir.”

Roland went to the mantelpiece; and, having inspected the dirty envelope for a moment with fastidious distaste, opened it in a gingerly manner.

“The box appears to me, sir,” continued Bryce, “to contain something alive. It seemed to me that I received the impression of something squirming.”

“Good Lord!” exclaimed Roland, staring at the letter.

“Sir?”

“It’s a snake. That fool has sent me a snake. Of all the——”

A hearty ringing at the front-door bell interrupted him. Bryce, rising from the suit-case, vanished silently. Roland continued to regard the unwelcome gift with a peevish frown.

“Miss Wickham, sir,” said Bryce at the door.

The visitor, who walked springily into the room, was a girl of remarkable and rather impish beauty. She resembled a particularly good-looking schoolboy who had dressed up in his sister’s clothes. She appeared, from the way she moved, to be built of whalebone and indiarubber; and there was a vitality in her bright hazel eyes which for years had caused nervous relatives to wonder apprehensively what she was going to be up to next.

“Ah!” she said, cocking a bright eye at the suit-case. “I’m glad you’re bustling about. We ought to be starting soon. I’m going to drive you down in the two-seater.” She began a restless tour of the room. “Hullo!” she said, arriving at the box. “What might this be?” She shook it experimentally. “I say! There’s something squishy inside!”

“Yes, it’s——”

“Roland,” said Miss Wickham, having conducted further experiments, “immediate investigation is called for. Inside this box, old dear, there is most certainly some living organism. When you shake it, it distinctly squishes.”

“It’s all right. It’s only a snake.”

“Snake!”

“Perfectly harmless,” he hastened to assure her. “The fool expressly states that. Not that it matters, because I’m going to send it straight back, unopened.”

Miss Wickham squeaked with pleased excitement.

“Who’s been sending you snakes?”

Roland coughed diffidently.

“I happened to—er—save a man’s life last night. I was coming along at the corner of Duke Street——”

“Now, isn’t that an extraordinary thing?” said Miss Wickham, meditatively. “Here have I lived all these years and never thought of getting a snake!”

“——when a man——”

“The one thing every young girl should have.”

“——slipped off the pavement——”

“There are the most tremendous possibilities in a snake. The diner-out’s best friend. Pop it on to the table after the soup and be Society’s pet.”

Roland, though nothing, of course, could shake his great love, was conscious of a passing feeling of annoyance.

“I’ll tell Bryce to take the thing back to the man,” he said, abandoning his story as a total loss.

“Take it back?” said Miss Wickham, amazed. “But, Roland, what frightful waste! Why, there are moments in life when knowing where to lay your hand on a snake means more than words can tell.” She started. “Golly! Didn’t you once say that old Sir Joseph What’s-his-name—the beak, you know—was your uncle? He fined me five of the best yesterday for absolutely crawling along Piccadilly. He needs a sharp lesson. He must be taught that he can’t go about the place persecuting the innocent like that. I’ll tell you what. Ask him to lunch here and hide the thing in his napkin! That’ll make him think a bit!”

“No, no!” cried Roland, shuddering strongly.

“Roland! For my sake!”

“No, no, really!”

“And you’ve said dozens of times that you would do anything in the world for me!” She mused. “Well, at least let me tie a string to it and dangle it out of window in front of the next old lady that comes along.”

“No, no, please! I must send it back to the man.”

Miss Wickham’s discontent was plain, but she seemed to accept defeat.

“Oh, all right, if you’re going to refuse me every little thing! But let me tell you, my lad, that you’re throwing away the laugh of a lifetime. Wantonly and callously chucking it away. Where is Bryce? Gone to earth in the kitchen, I suppose. I’ll go and give him the thing while you strap the suit-case. We ought to be starting, or we sha’n’t get there by tea-time.”

“Let me do it.”

“No, I’ll do it.”

“You mustn’t trouble.”

“No trouble,” said Miss Wickham, amiably.

IN this world, as has been pointed out in various ways by a great many sages and philosophers, it is wiser for the man who shrinks from being disappointed not to look forward too keenly to moments that promise pleasure. Roland Attwater, who had anticipated considerable enjoyment from his drive down to Skeldings Hall, soon discovered, when the car had threaded its way through the London traffic and was out in the open country, that the conditions were not right for enjoyment. Miss Wickham did not appear to share the modern girl’s distaste for her home. She plainly wanted to get there as quickly as possible. It seemed to Roland that from the time they left High Barnet to the moment when, with a grinding of brakes, they drew up at the door of Skeldings Hall the two-seater had only touched Hertfordshire at odd spots.

Yet, as they alighted, Roberta Wickham voiced a certain dissatisfaction with her work.

“Forty-three minutes,” she said, frowning at her watch. “I can do better than that.”

“Can you?” gulped Roland. “Can you, indeed?”

“Well, we’re in time for tea, anyhow. Come in and meet the mater. Forgotten Sports of the Past—Number Three, Meeting the Mater.”

Roland met the mater. The phrase, however, is too mild and inexpressive and does not give a true picture of the facts. He not merely met the mater; he was engulfed and swallowed up by the mater. Lady Wickham, that popular novelist (“Strikes a singularly fresh note.”—R. Moresby Attwater in the New Examiner), was delighted to see her guest. Welcoming Roland to her side, she proceeded to strike so many singularly fresh notes that he was unable to tear himself away till it was time to dress for dinner. She was a large, severe woman, with a voice that never stopped, and she was still talking with unimpaired volubility on the subject of her books, of which Roland had been kind enough to write so appreciatively, when the gong went.

“Is it as late as that?” she said, surprised, releasing Roland, who had thought it later. “We shall have to go on with our little talk after dinner. You know your room? No? Oh, well, Claude will show you. Claude, will you take Mr. Attwater up with you? His room is at the end of your corridor. By the way, you don’t know each other, do you? Sir Claude Lynn—Mr. Attwater.”

The two men bowed; but in Roland’s bow there was not that heartiness which we like to see in our friends when we introduce them to fellow-guests. A considerable part of the agony which he had been enduring for the last two hours had been caused not so much by Lady Wickham’s eloquence, though that had afflicted him sorely, as by the spectacle of this man Lynn, whoever he might be, monopolizing the society of Bobbie Wickham in a distant corner. There had been to him something intolerably possessive about the back of Sir Claude’s neck as he bent towards Miss Wickham. It was the neck of a man who is being much more intimate and devotional than a jealous rival cares about.

The close-up which he now received of this person did nothing to allay Roland’s apprehension. The man was handsome, sickeningly handsome, with just that dark, dignified, clean-cut handsomeness which attracts impressionable girls. It was, indeed, his dignity that so oppressed Roland now. There was that about Sir Claude Lynn’s calm and supercilious eye that made a fellow feel that he belonged to entirely the wrong set in London and that his trousers were bagging at the knees.

“A most delightful man,” whispered Lady Wickham, as Sir Claude moved away to open the door for Bobbie. “Between ourselves, the original of Captain Mauleverer, D.S.O., in my ‘Blood Will Tell.’ Very old family, ever so much money. Plays polo splendidly. And tennis. And golf. A superb shot. Member for East Bittlesham, and I hear on all sides that he may be in the Cabinet any day.”

“Indeed?” said Roland, coldly.

IT seemed to Lady Wickham, as she sat with him in her study after dinner—she had stated authoritatively that he would much prefer a quiet chat in that shrine of literature to any shallow revelry that might be going on elsewhere—that Roland was a trifle distrait. Nobody could have worked harder to entertain him than she. She read him the first seven chapters of the new novel on which she was engaged, and told him in gratifying detail the plot of the rest of it, but somehow all did not seem well. The young man, she noticed, had developed a habit of plucking at his hair; and once he gave a sharp, gulping cry which startled her. Lady Wickham began to feel disappointed in Roland, and was not sorry when he excused himself.

“I wonder,” he said, in a rather overwrought sort of way, “if you would mind if I just went and had a word with Miss Wickham? I—I—there’s something I wanted to ask her.”

“Certainly,” said Lady Wickham, without warmth. “You will probably find her in the billiard-room. She said something about having a game with Claude. Sir Claude is wonderful at billiards. Almost like a professional.”

Bobbie was not in the billiard-room, but Sir Claude was, practising dignified cannons which never failed to come off. At Roland’s entrance he looked up like an inquiring statue.

“Miss Wickham?” he said. “She left half an hour ago. I think she went to bed.”

He surveyed Roland’s flushed dishevelment for a moment with a touch of disapproval, then resumed his cannons. Roland, though he had that on his mind concerning which he desired Miss Wickham’s counsel and sympathy, felt that it would have to stand over till the morning. Meanwhile, lest his hostess should pop out of the study and recapture him, he decided to go to bed himself.

He had just reached the passage where his haven lay, when a door which had apparently been standing ajar opened and Bobbie appeared, draped in a sea-green negligée of such a calibre that Roland’s heart leaped convulsively and he clutched at the wall for support.

“Oh, there you are,” she said, a little petulantly. “What a time you’ve been!”

“Your mother was——”

“Yes, I suppose she would be,” said Miss Wickham, understandingly. “Well, I only wanted to tell you about Sidney.”

“Sidney? Do you mean Claude?”

“No. Sidney. The snake. I was in your room just after dinner, to see if you had everything you wanted, and I noticed the box on your dressing-table.”

“I’ve been trying to get hold of you all the evening to ask you what to do about that,” said Roland, feverishly. “I was most awfully upset when I saw the beastly thing. How Bryce came to be such an idiot as to put it in the car——”

“He must have misunderstood me,” said Bobbie, with a clear and childlike light shining in her hazel eyes. “I suppose he thought I said, ‘Put this in the back’ instead of ‘Take this back.’ But what I wanted to say was that it’s all right.”

“All right?”

“Yes. That’s why I’ve been waiting up to see you. I thought that, when you went to your room and found the box open, you might be a bit worried.”

“The box open!”

“Yes. But it’s all right. It was I who opened it.”

“Oh, but I say—you—you oughtn’t to have done that. The snake may be roaming about all over the house.”

“Oh, no, it’s all right. I know where it is.”

“That’s good.”

“Yes, it’s all right. I put him in Claude’s bed.”

Roland Attwater clutched at his hair as violently as if he had been listening to chapter six of Lady Wickham’s new novel.

“You—you—you—what?”

“I put him in Claude’s bed.”

Roland uttered a little whinnying sound, like a very old horse a very long way away.

“Put him in Claude’s bed!”

“Put him in Claude’s bed.”

“But—but—but why?”

“Why not?” asked Miss Wickham, reasonably.

“But—oh, my heavens!”

“Something on your mind?” inquired Miss Wickham, solicitously.

“It will give him an awful fright.”

“Jolly good for him. I was reading an article in the evening paper about it. Did you know that fear increases the secretory activity of the thyroid, suprarenal, and pituitary glands? Well, it does. Bucks you up, you know. Regular tonic. It’ll be like a day at the seaside for old Claude when he puts his bare foot on Sidney. Well, I must be turning in. Got that schoolgirl complexion to think about. Good night.”

FOR some minutes after he had tottered to his room, Roland sat on the edge of the bed in deep meditation. At one time it seemed as if his reverie was going to take a pleasant turn. This was when the thought presented itself to him that he must have overestimated the power of Sir Claude’s fascination. A girl could not, he felt, have fallen very deeply under a man’s spell if she started filling his bed with snakes the moment she left him.

For an instant, as he toyed with this heartening reflection, something remotely resembling a smile played about Roland’s sensitive mouth. Then another thought came to wipe the smile away—the realization that, while the broad general principle of putting snakes in Sir Claude’s bed was entirely admirable, the flaw in the present situation lay in the fact that this particular snake could be so easily traced to its source. The butler, or whoever had taken his luggage upstairs, would be sure to remember carrying up a mysterious box. Probably it had squished as he carried it and was already the subject of comment in the servants’ hall. Discovery was practically certain.

Roland rose jerkily from his bed. There was only one thing to be done, and he must do it immediately. He must go to Sir Claude’s room and retrieve his lost pet. He crept to the door and listened carefully. No sound came to disturb the stillness of the house. He stole out into the corridor.

It was at this precise moment that Sir Claude Lynn, surfeited with cannons, put on his coat, replaced his cue in the rack, and came out of the billiard-room.

IF there is one thing in this world that should be done quickly or not at all, it is the removal of one’s personal snake from the bed of a comparative stranger. Yet Roland, brooding over the snowy coverlet, hesitated. All his life he had had a horror of crawling and slippery things. At his private school, while other boys had fondled frogs and achieved terms of intimacy with slow-worms, he had not been able to bring himself even to keep white mice. The thought of plunging his hand between those sheets and groping for an object of such recognized squishiness as Sidney appalled him. And, even as he hesitated, there came from the corridor outside the sound of advancing footsteps.

Roland was not by nature a resourceful young man, but even a child would have known what to do in this crisis. There was a large cupboard on the other side of the room, and its door had been left invitingly open. In the rapidity with which he bolted into this his uncle Joseph would no doubt have seen further convincing evidence of his rabbit-hood. He reached it and burrowed behind a mass of hanging clothes just as Sir Claude entered the room.

IT was some small comfort to Roland—and at the moment he needed what comfort he could get, however small—to find that there was plenty of space in the cupboard. And what was even better, seeing that he had had no time to close the door, it was generously filled with coats, overcoats, raincoats, and trousers. Sir Claude Lynn was evidently a man who believed in taking an extensive wardrobe with him on country-house visits; and, while he deplored the dandyism which this implied, Roland would not have had it otherwise. Nestling in the undergrowth, he peered out between a raincoat and a pair of golfing knickerbockers. A strange silence had fallen, and he was curious to know what his host was doing with himself.

At first he could not sight him; but, shifting slightly to the left, he brought him into focus, and discovered that in the interval that had passed Sir Claude had removed nearly all his clothes and was now standing before the open window, doing exercises.

It was not prudery that caused this spectacle to give Roland a sharp shock. What made him start so convulsively was the man’s horrifying aspect as revealed in the nude. Downstairs, in the conventional dinner-costume of the well-dressed man, Sir Claude Lynn had seemed robust and soldierly, but nothing in his appearance then had prepared Roland for the ghastly physique which he exhibited now. He seemed twice his previous size, as if the removal of constricting garments had caused him to bulge in every direction. When he inflated his chest, it looked like a barrel. And, though Roland in the circumstances would have preferred any other simile, there was only one thing to which his rippling muscles could be compared. They were like snakes, and nothing but snakes. They heaved and twisted beneath his skin just as Sidney was presumably even now heaving and twisting beneath the sheets.

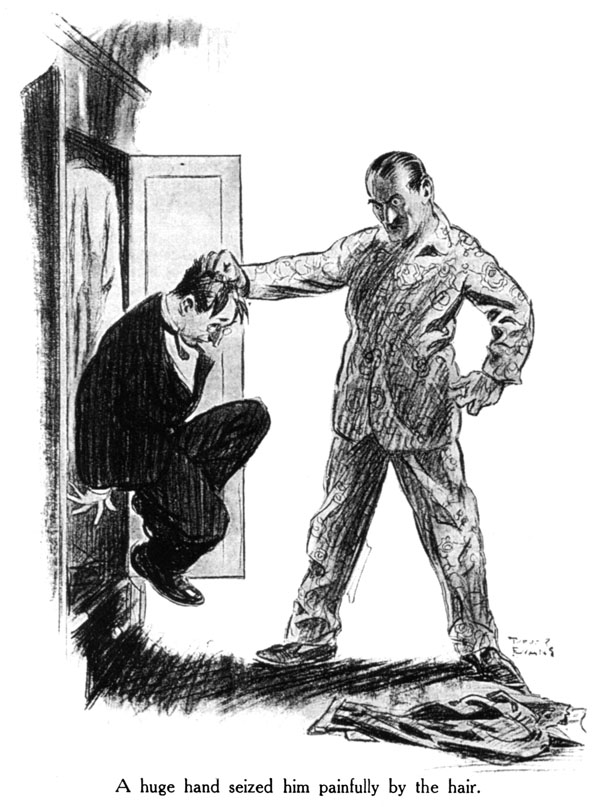

If ever there was a man, in short, in whose bedroom one would rather not have been concealed in circumstances which might only too easily lead to a physical encounter, that man was Sir Claude Lynn; and Roland, seeing him, winced away with a shudder so violent that a coat-hanger which had been trembling on the edge of its peg fell with a disintegrating clatter.

There was a moment of complete silence: then the trousers behind which he cowered were snatched away, and a huge hand, groping like the tentacle of some dreadful marine monster, seized him painfully by the hair and started pulling.

There was a moment of complete silence: then the trousers behind which he cowered were snatched away, and a huge hand, groping like the tentacle of some dreadful marine monster, seized him painfully by the hair and started pulling.

“Ouch!” said Roland, and came out like a winkle at the end of a pin.

A modesty which Roland, who was modest himself, should have been the first to applaud had led the other to clothe himself hastily for this interview in a suit of pyjamas of a stupefying mauve. In all his life Roland had never seen such a colour-scheme; and in some curious way the brilliance of them seemed to complete his confusion. The result was that, instead of plunging at once into apologies and explanations, he remained staring with fallen jaw; and his expression, taken in conjunction with the fact that his hair, rumpled by the coats, appeared to be standing on end, supplied Sir Claude with a theory which seemed to cover the case. He remembered that Roland had had much the same cockeyed look when he had come into the billiard-room. He recalled that immediately after dinner Roland had disappeared and had not joined the rest of the party in the drawing-room. Obviously the fellow must have been drinking like a fish in some secret part of the house for hours.

“Get out!” he said curtly, taking Roland by the arm with a look of disgust and leading him sternly to the door. An abstemious man himself, Sir Claude Lynn had a correct horror of excess in others. “Go and sleep it off. I suppose you can find your way to your room? It’s the one at the end of the corridor, as you seem to have forgotten.”

“But listen——”

“I cannot understand how a man of any decent upbringing can make such a beast of himself.”

“Do listen!”

“Don’t shout like that,” snapped Sir Claude, severely. “Good heavens, man, do you want to wake the whole house? If you dare to open your mouth again, I’ll break you into little bits.”

Roland found himself out in the passage, staring at a closed door. Even as he stared it opened sharply, and the upper half of the mauve-clad Sir Claude popped out.

“No drunken singing in the corridor, mind!” said Sir Claude, sternly, and disappeared.

It was a little difficult to know what to do. Sir Claude had counselled slumber, but the suggestion was scarcely a practical one. On the other hand, there seemed nothing to be gained by hanging about in the passage. With slow and lingering steps Roland moved towards his room, and had just reached it when the silence of the night was rent by a shattering scream; and the next moment there shot through the door he had left a large body. And, as Roland gazed dumbly, a voice was raised in deafening appeal.

“Shot-gun!” vociferated Sir Claude. “Help! Shot-gun! Bring a shot-gun, somebody!”

There was not the smallest room for doubt that the secretory activity of his thyroid, suprarenal, and pituitary glands had been increased to an almost painful extent.

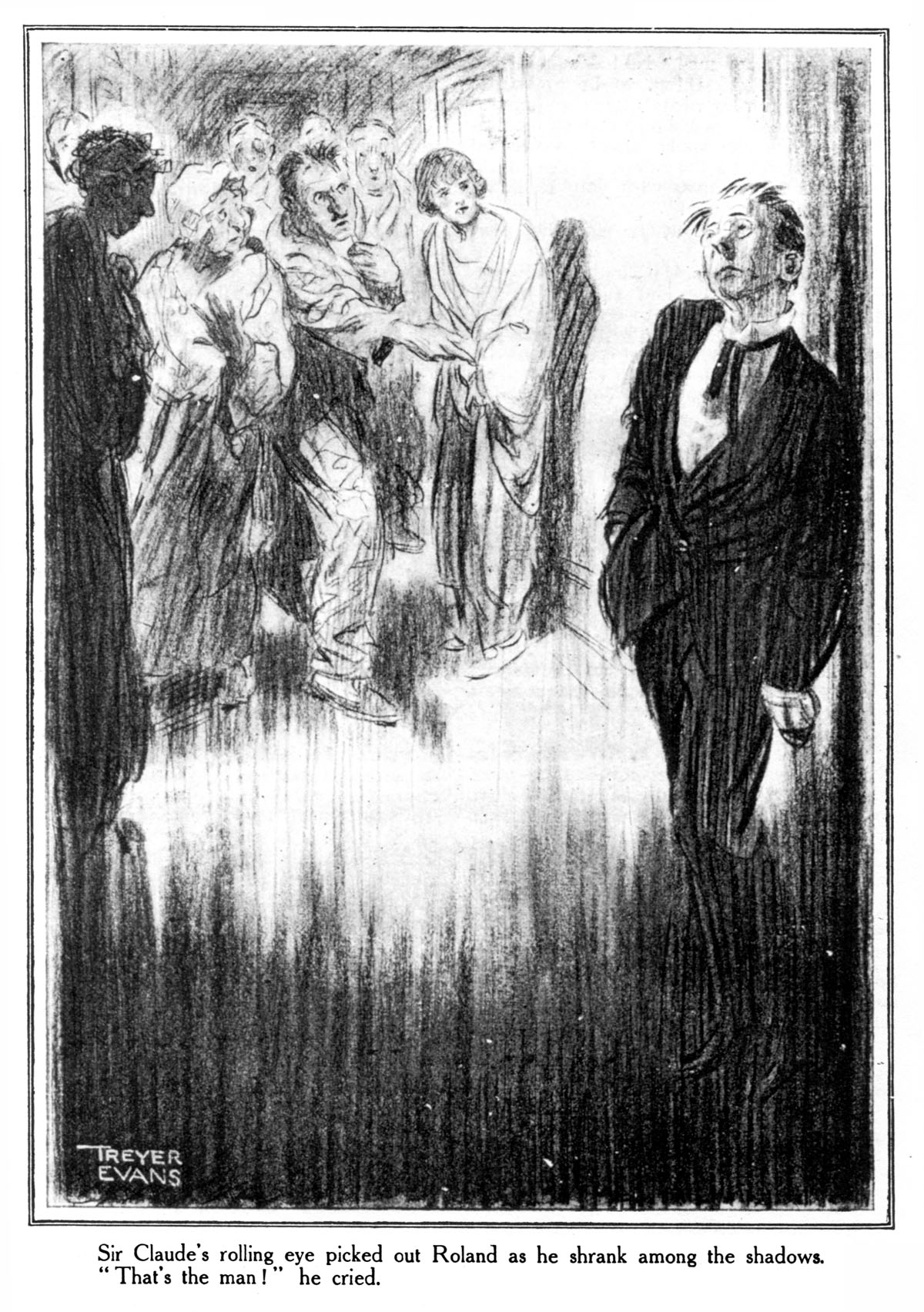

It is only in the most modern and lively country houses that this sort of thing can happen without attracting attention. So quickly did the corridor fill that it seemed to Roland as if dressing-gowned figures had shot up through the carpet. Among those present he noticed Lady Wickham in blue, her daughter Roberta in green, three male guests in bath-robes, the under-housemaid in curl-papers, and Simmons, the butler, completely and correctly clad in full afternoon costume. They were all asking what was the matter, but, as Lady Wickham’s penetrating voice o’ertopped the rest, it was to her that Sir Claude turned to tell his story.

“A snake?” said Lady Wickham, interested.

“A snake.”

“In your bed?”

“In my bed.”

“Most unusual,” said Lady Wickham, with a touch of displeasure.

Sir Claude’s rolling eye, wandering along the corridor, picked out Roland as he shrank among the shadows. He pointed at him with such swift suddenness that his hostess only saved herself from a nasty blow by means of some shifty footwork.

“That’s the man!” he cried.

Lady Wickham, already ruffled, showed signs of peevishness.

“My dear Claude,” she said, with a certain asperity, “do come to some definite decision. A moment ago you said there was a snake in your room; now you say it was a man. Besides, can’t you see that that is Mr. Attwater? What would he be doing in your room?”

“I’ll tell you what he was doing. He was putting that infernal snake in my bed. I found him there.”

“Found him there? In your bed?”

“In my cupboard. Hiding. I hauled him out.”

All eyes were turned upon Roland. His own he turned with a look of wistful entreaty upon Roberta Wickham. A cavalier of the nicest gallantry, nothing, of course, would induce him to betray the girl; but surely she would appreciate that the moment had come for her to step forward and clear a good man’s name with a full explanation.

He had been too sanguine. A pretty astonishment lit up Miss Wickham’s lovely eyes. But her equally lovely mouth did not open.

“But Mr. Attwater has no snake,” argued Lady Wickham. “He is a well-known man-of-letters. Well-known men-of-letters,” she said, stating a pretty generally recognized fact, “do not take snakes with them when they go on visits.”

A new voice joined in the discussion.

“Begging your pardon, your ladyship.”

It was the voice of Simmons, grave and respectful.

“Begging your pardon, your ladyship, it is my belief that Mr. Attwater did have a serpent in his possession. Thomas, who conveyed his baggage to his room, mentioned a cardboard box that seemed to contain something alive.”

From the expression of the eyes that once more raked him in his retirement, it was plain that the assembled company were of the opinion that it was Roland’s turn to speak. But speech was beyond him. He had been backing slowly for some little time, and now, as he backed another step, the handle of his bedroom door insinuated itself into the small of his back. It was almost as if the thing were hinting to him that refuge that lay beyond.

He did not resist the kindly suggestion. With one quick, emotional movement he turned, plunged into his room, and slammed the door behind him.

From the corridor without came the sound of voices in debate. He was unable to distinguish words, but the general trend of them was clear. Then silence fell.

Roland sat on his bed, staring before him. He was roused from his trance by a tap on the door.

“Who’s that?” he cried, bounding up. His eye was wild. He was prepared to sell his life dearly.

“It is I, sir. Simmons.”

“What do you want?”

The door opened a few inches. Through the gap there came a hand. In the hand was a silver salver. On the salver lay something squishy that writhed and wriggled.

“Your serpent, sir,” said the voice of Simmons.

IT was the opinion of Roland Attwater that he was now entitled to the remainder of the night in peace. The hostile forces outside must now, he felt, have fired their last shot. He sat on his bed, thinking deeply, if incoherently. From time to time the clock on the stables struck the quarters, but he did not move. And then into the silence it seemed to him that some sound intruded—a small tapping sound that might have been the first tentative efforts of a very young woodpecker just starting out in business for itself. It was only after this small noise had continued for some moments that he recognized it for what it was.

Somebody was knocking softly on his door.

There are moods in which even the mildest man will turn to bay, and there gleamed in Roland Attwater’s eyes as he strode to the door and flung it open a baleful light. And such was his militant condition that, even when he glared out and beheld Roberta Wickham, still in that green negligée, the light did not fade away. He regarded her malevolently.

“I thought I’d better come and have a word with you,” whispered Miss Wickham.

“Indeed?” said Roland.

“I wanted to explain.”

“Explain!”

“Well,” said Miss Wickham, “you may not think there’s any explanation due to you, but I really feel there is. Oh, yes, I do. You see, it was this way. Claude had asked me to marry him.”

“And so you put a snake in his bed? Of course! Quite natural!”

“Well, you see, he was so frightfully perfect and immaculate and dignified and—oh, well, you’ve seen him for yourself, so you know what I mean. He was too darned overpowering—that’s what I’m driving at—and it seemed to me that if I could only see him really human and undignified—just once—I might—well, you see what I mean?”

“And the experiment, I take it, was successful?”

Miss Wickham wriggled her small toes inside her slippers.

“It depends which way you look at it. I’m not going to marry him, if that’s what you mean.”

“I should have thought,” said Roland, coldly, “that Sir Claude behaved in a manner sufficiently—shall I say human?—to satisfy even you.”

Miss Wickham giggled reminiscently.

“He did leap, didn’t he? He reminded me of those hills in the Bible. ‘Why skip ye so, ye high hills?’ Do you remember? But it’s all off, just the same.”

“Might I ask why?”

“Those pyjamas, old dear,” said Miss Wickham, firmly. “The moment I caught a glimpse of them, I said to myself, ‘No wedding bells for me!’ No! I’ve seen too much of life, old thing, to be optimistic about a man who wears mauve pyjamas.” She plunged for a space into maiden meditation. When she spoke again, it was on another aspect of the affair. “I’m afraid mother is rather cross with you, Roland.”

“You surprise me!”

“Never mind. You can slate her next novel.”

“I intend to,” said Roland, grimly, remembering what he had suffered in the study from chapters one to seven of it.

“But meanwhile I don’t think you had better meet her again just yet. Do you know, I really think the best plan would be for you to go away to-night without saying good-bye. There is a very good milk-train which gets you into London at six-forty-five.”

“When does it start?”

“At three-fifteen.”

“I’ll take it,” said Roland.

There was a pause. Roberta Wickham drew a step closer.

“Roland,” she said, softly, “you were a dear not to give me away. I do appreciate it so much.”

“Not at all!”

“There would have been an awful row. I expect mother would have taken away my car.”

“Ghastly!”

“I want to see you again quite soon, Roland. I’m coming up to London next week. Will you give me lunch? And then we might go and sit in Kensington Gardens or somewhere where it’s quiet.”

Roland eyed her fixedly.

“I’ll drop you a line,” he said.

SIR JOSEPH MORESBY was an early breakfaster. The hands of the clock pointed to five minutes past eight as he entered his dining-room with a jaunty and hopeful step. There were, his senses told him, kidneys and bacon beyond that door. To his surprise he found that there was also his nephew Roland. The young man was pacing the carpet restlessly. He had a rumpled look, as if he had slept poorly, and his eyes were pink about the rims.

“Roland!” exclaimed Sir Joseph. “Good gracious! What are you doing here? Didn’t you go to Skeldings after all?”

“Yes, I went,” said Roland in a strange, toneless voice.

“Then what——?”

“Uncle Joseph,” said Roland, “you remember what we were talking about at dinner? Do you really think Lucy would have me if I asked her to marry me?”

“What! My dear boy, she’s been in love with you for years.”

“Is she up yet?”

“No. She doesn’t breakfast till nine.”

“I’ll wait.”

Sir Joseph grasped his hand.

“Roland, my boy——” he began.

But there was that on Roland’s mind that made him unwilling to listen to set speeches.

“Uncle Joseph,” he said, “do you mind if I join you for a bite of breakfast?”

“My dear boy, of course——”

“Then I wish you would ask them to be frying two or three eggs and another rasher or so. While I’m waiting I’ll be starting on a few kidneys.”

IT was ten minutes past nine when Sir Joseph happened to go into the morning-room. He had supposed it empty, but he perceived that the large armchair by the window was occupied by his nephew Roland. He was leaning back with the air of one whom the world is treating well. On the floor beside him sat Lucy, her eyes fixed adoringly on the young man’s face.

“Yes, yes,” she was saying. “How wonderful! Do go on, darling.”

Sir Joseph tiptoed out, unnoticed. Roland was speaking as he softly closed the door.

“Well,” Sir Joseph heard him say, “it was raining, you know, and just as I reached the corner of Duke Street——”

(Another P. G. Wodehouse story next month.)

Notes:

This is the second appearance of this story, after its debut in the Saturday Evening Post of December 20, 1924, and collected in Mr. Mulliner Speaking (1929/30) in a slightly shorter version, but with an added Anglers’ Rest introduction featuring Mr. Mulliner, a cousin of Lady Wickham.

Even though printed in the January 1925 issue of the Strand, it appeared with a 1924 copyright notice, which seems reasonable, since the January issue appeared on newsstands in late December. Thus under USA copyright law it fell into public domain at the end of 2019.

Annotations to this story appear as endnotes at the Saturday Evening Post link above.

Madame Eulalie’s Rare Plums

Madame Eulalie’s Rare Plums