The Strand Magazine, March 1912

CHAPTER VII.

betty meets a friend in need.

HE idea of flight had not occurred

to Betty immediately. On leaving Mr. Scobell’s villa she had walked aimlessly

out along the hillside. At first her mind was stunned, but gradually, as blood

begins to circulate in a frozen limb, thought had returned, slowly at first,

then in a wave that seethed and burned and tortured. She realized now, as she

had never realized before, the place John had held in her life. That it should

have been he, of all men, who was Mr. Scobell’s obsequious employé, the man

whom the Casino was paying to marry her, complacently ready to earn his wages

by counterfeiting love!

HE idea of flight had not occurred

to Betty immediately. On leaving Mr. Scobell’s villa she had walked aimlessly

out along the hillside. At first her mind was stunned, but gradually, as blood

begins to circulate in a frozen limb, thought had returned, slowly at first,

then in a wave that seethed and burned and tortured. She realized now, as she

had never realized before, the place John had held in her life. That it should

have been he, of all men, who was Mr. Scobell’s obsequious employé, the man

whom the Casino was paying to marry her, complacently ready to earn his wages

by counterfeiting love!

She must go away. That decision stood out, clear and definite, in the chaos of her thoughts. To meet him, to see the man she loved plunging into shame before her eyes, would be pain beyond bearing.

Below, across the valley of vineyards and glowing mimosa, the dome of the Casino caught the sun and flashed out in a blaze of gold. Beyond it, in the little harbour, lay the Marseilles packet, lazily breathing smoke as it prepared for its journey to the mainland. She looked at her watch. She would only just have time to catch the boat. She turned, and hurried back the way she had come.

Paris, when she arrived at the Gare du Lyon in the grey of a rainy morning, had much the same effect on Betty as London had had on John during his first morning of independence. She had been in Paris before, but then she had been rich, and the city had smiled upon her.

She had fled from Mervo with nothing but a few necessaries thrown together in a small bag, and there was nothing to detain her at the Gare du Lyon. She went straight to the Girdle Railway, and found a seat on the first train.

At the Gare du Nord all was movement and confusion. Obvious Anglo-Saxons wandered about like lost sheep, miserably conscious of linguistic deficiencies, or stood guard over suit-cases with almost a truculent air of defence.

Presently a group of four attracted Betty’s attention. Three were plainly Americans, a typical doing-Europe family—the father grey, patient, and a little bent; the mother, flying the brown veil, the Jolly Roger of the travelling American, resolute and unbeaten, but for the moment flustered; the daughter slim, trim, straight, jaunty, and clean-cut, with that indefinable glitter that stamps the American girl. The fourth member of the group was a polite semaphore in a blue blouse, and from the attitude of the three travellers it seemed that the kindly feelings which every good American harbours towards the French in return for benefits received from the late M. Lafayette were, in the case of this particular member of the nation, in danger of being forgotten.

Betty’s heart went out to the exiles. She stopped as she reached them, and hesitated. Then she caught the distracted eye of the lady in the brown veil, and answered its unspoken appeal.

“Can I help you?” she said. “I speak French.”

No shipwrecked mariners sighting a sail could have exhibited more animation than did the rescued family. The father’s patient face lit up as if somebody had pressed a switch. His wife’s eyes lost their haggard look. The daughter, who was nearest, seized Betty unaffectedly in her arms and hugged her.

Betty laughed.

“What is the trouble?” she asked. “What do you want me to tell the porter?”

“We want our baggage,” said the patient man, pathetically. “We let ’em separate us from it at the hotel, and that’s the last we’ve seen of it.”

“Oh, that is quite simple. I’ll explain to him in a moment. Are you going by the boat-train?”

“That’s right. We want to get to England, if they’ll let us.”

Betty explained matters to the porter.

“It will be all right now,” she said. “Just go with him and he will do everything that’s necessary.”

She turned to move away, but a universal exclamation of dismay stopped her.

“Say, you aren’t going to leave us?” queried the head of the family, anxiously.

“You want to take command of this outfit,” said his daughter, “or we don’t stand a dog’s chance. Are you travelling by the boat-train, too? Well, won’t you join us? This country’s got us all scared so that we don’t know what we’re doing.”

“If you really think I should be any help——”

“Help?” echoed the three, ecstatically.

“Then I will,” said Betty. “But there really isn’t anything for me to do.”

“Don’t you believe it,” said the girl. “You’ll save our lives. This is going to put you in the Carnegie Medal class.”

“Let’s get away into another compartment, where we can talk,” suggested the girl, when every obstacle had been successfully negotiated and they had won through to the train. “Ma likes to read on a journey, and the old gentleman will have to have a smoke to steady him after all this.”

They moved down the corridor till they found an empty compartment. The American girl removed her hat, settled her hair at the mirror, and sat down with a sigh of content.

“Thank goodness,” she said, as the train gathered speed. “No more Paris for me till I’ve had a squad of professors put me next to the language. It’s a funny thing. I used to tell people I was crazy to go to Paris—and now I guess that I must have been. London’ll be better, I reckon.”

“Are you going to stay in London?” asked Betty.

“Not for long. We—— But, say, let’s get acquainted. What’s your name? Mine’s Della Morrison.”

“Mine——” Betty stopped. The thought had occurred to her that she had better change her name. “Mine is Brown,” she said.

“What’s your first name?”

“Betty.”

“I shall call you Betty. And you call me Della. What I was saying before we—— Oh, yes. We’re going to stay in London for a while, then we’re going to rent a swell place in the country somewhere. A friend of ours is fixing it for us now. Something Court’s the place he’s trying to get. A court’s something like a castle, isn’t it? Fancy me in a castle! Oh, well,” she said, resignedly, “it’s all in a lifetime!”

“Surely you’ll like the castle?” said Betty, smiling.

Della looked doubtful.

“I’m not so sure,” she said. “You see, it’s this way. I don’t know much about castles, but I do know that we aren’t in the castle class. A month ago the old gentleman was paying-cashier in a bank, and I was keeping one eye on the boss and the other on the pad or playing ragtime on the typewriter. Well, we were as good at our jobs as the next person, but that’s no reason why we should make any particular hit with the effete aristocracy, is it? If you ask me, our team’s going to get the hook before we know what’s hit us. And I haven’t any use for society, either. I’m not saying I’m not glad to be quit of working at the office, but outside that I don’t seem to care much. And there’s another thing. Just before the news came that pa had had all that money left him, I got engaged.”

She sighed.

“Yes?” said Betty, encouragingly.

“To a boy in the office I was in in New York,” continued Della. “Tom Spiller his name is. He was bill-clerk there. Say, do you like red hair?” she broke off. “In a man, I mean. Tom’s got red hair. You’d like Tom.”

“I wish I could meet him.”

“Gee, I wish I could, too,” sighed Della. “You see, pa and ma don’t know anything about me being engaged. I was getting myself worked up to tell them, and, just as I was good and ready, along comes all this sudden wealth. And now I don’t know what to do about it. I daren’t tell them now. Ma’s got such large ideas. She don’t think about anybody lower than an earl these days. But, say, nobody’s going to make me give Tom up.”

“Of course not.”

“If I was good enough for him to marry when I was a stenog., he’s good enough for me to marry when I’m a plute.”

“Of course.”

Della looked at her affectionately.

“You’re a comfort, Betty,” she said. “I’m mighty glad I met you.” She sat up, struck with an idea. “Say, what are you going to do when you get to England?”

“I don’t know.”

“Then, say, you’ve got to stay with us as long as ever you can. In London first, and then in the country. Gee, it’ll be a comfort having you around.”

Betty flushed. “I’m afraid——” she began. “I don’t think—— I’m afraid I can’t, Della,” she said. “You don’t understand,” she went on, nervously. “You think I’m—— I mustn’t pay visits; I have got to find some way of earning my living. Except for the little money I have with me I haven’t a penny in the world.”

Della sat thinking. “I’ve got it,” she cried. “Lord Arthur said I’d better have one when I got to England. He’s the guy—the lord, I mean—who’s fixing the deal about the castle. He said that I should want a companion—someone to go around with—because ma couldn’t always be tagging along. You’re it!”

“But——”

“Don’t make objections. It’s settled. So you’ll come to the castle after all. We’ll have the greatest time. I’ll go and tell ma.”

Mr. and Mrs. Morrison received the news with flattering approval. The spectacle of Betty producing order out of chaos at the Gare du Nord and speaking the mysterious tongue of France with the insouciance of a native had left a deep impression on their minds. They endorsed her appointment as Della’s companion with one voice.

The rest of the journey passed swiftly for Betty. A great weight had been lifted from her mind. Now that everything was settled she saw how terrifying the vague future had really been, and how reckless her headlong dash into the unknown.

The Morrisons had engaged rooms at the Cecil. Della, her magnificent energy proof against the fatigue of a journey from Paris, took Betty off to a theatre after dinner, and on their return sat on her bed talking till Betty’s answers became drowsy and disconnected.

It was late on the following morning when Betty came downstairs. Inquiring for the Morrisons, she was handed a note from Della, informing her that they had gone off to do Westminster Abbey, but would be back to lunch at one.

With more than an hour to pass, Betty wandered out into the Strand. It was nearly one o’clock when she returned. As she began to mount the hotel steps a taxi-cab drew up, and a man with a light moustache emerged. He paid the driver and turned to enter the hotel. Then he saw Betty, and a look of recognition came into his face.

“Miss Silver!” he said.

It was Lord Arthur Hayling.

CHAPTER VIII.

lord arthur is puzzled.

Betty took his outstretched hand and forced a smile, but she was disconcerted. If Lord Arthur was not the one man in the world whom she preferred not to meet, he was not far from being that. Even had her circumstances been other than they were, she would have wished to avoid him, for it had been at their last meeting that she had refused his stately and well-expressed offer of marriage.

“This is a most delightful surprise,” said Lord Arthur. He stroked his straw-coloured moustache. “Are you staying in the hotel?”

“Yes,” she said. “Are you?“

“I have an engagement to meet some people here for lunch at one. Americans. A Mr. Morrison and his family.”

“Morrison?”

“You know them? I should not have imagined that you would have come across them. They are excellent people,” he said, with a sub-tinkle of disapproval, “excellent people in every way; but, don’t you know—hardly——” He paused, leaving an eloquent gap. “But, perhaps,” he went on—hopefully, as it were—“these are not the same Morrisons that you know. The name is not an uncommon one. My acquaintance is a Mr. Richard Morrison. He was—ah—employed till recently, I believe, in some bank in New York. He inherited a fortune not long ago. His wife and daughter——”

Betty interrupted, speaking rapidly:—

“Yes, those are my Morrisons. I am travelling with them. That is to say——”

“Really?”

Lord Arthur’s blonde eyebrows rose the fraction of an inch. Although he himself was clinging to the Morrisons with the assiduity of a leech, and had for some time been turning over in his mind the idea of making Della the same handsome offer which Betty had declined at their last meeting, his caste prejudice had remained unaltered.

Lord Arthur Hayling was, in his curious way, a man of business, and to allow sentiment to interfere with business was a thing he would never have dreamed of doing. He intended to marry money; nothing would make him swerve from that determination; but he would have welcomed a chance to marry a woman who attracted him in a non-business way; and that was why Betty’s refusal had for the moment saddened him. He admired her as a woman scarcely less than as a human certified cheque, and to find her on intimate terms with these Morrisons was a surprise to him.

“Really?” he said again. Then, with tactful condescension: “They are most interesting people, are they not? Miss Morrison is charmingly quaint and lively.”

“Della is a dear,” said Betty, defiantly, in answer to the sub-tinkle.

“Quite so,” said his lordship.

He stroked his moustache, and Betty flushed. His attitude had the effect of ridding Betty of the nervousness which she had been feeling. She looked forward with a sort of grim pleasure to the effect of the bomb she was about to explode under his lordship’s nose.

“When I say I am travelling with the Morrisons,” she said, coolly, “I don’t mean as a friend. I am Miss Morrison’s paid companion.”

She was not disappointed. Lord Arthur Hayling, from boyhood up, had been steeped in the tradition that to display emotion is bad form and one of the things that are not done, but this piece of information cracked the shell of detached calm in which the years had encased him, and for a moment his jaw dropped and he gaped at Betty like any ordinary fellow whose father had been connected with trade.

He was badly shaken. Though Betty had refused his offer of marriage, he had not entirely despaired of winning her, and, meeting her in the company of mutual acquaintances, he had felt that Fate was working for him. And now, with a firm hand, she had upset his air-castle. It was not surprising that the shock should have produced a temporary dumbness.

He put the natural construction on her statement. If Betty was in the position of having to earn her living as a paid companion, it meant that Mr. Benjamin Scobell must have lost his fortune.

The narrowness of his escape shocked Lord Arthur. Suppose she had accepted him, and then this had happened!

Betty stood waiting for him to recover.

“They know me as Miss Brown,” she said. “Will you please remember that I am not Miss Silver any longer?”

“You have changed your name? Just so. Exactly.”

“Thank you,” said Betty.

There was an awkward silence. Lord Arthur wanted to find out all about Mr. Scobell’s downfall, but it was not easy to start. He was casting about in his mind for an opening, when a taxi-cab drew up beside them, and the Morrison party got out.

“Halloa!” said Della. “Do you two know each other?”

Lord Arthur prevaricated smoothly.

“I inquired for you in the hotel, and they told me that Miss Brown was the only member of your party who had not gone out, so we made each other’s acquaintance.”

“She can talk French,” said Della, irrelevantly. “Say, I’m starving. Let’s go scare up some lunch.”

During the meal Lord Arthur was silent. He had not yet adjusted himself to the alteration in Betty. Mentally, he was on the ground taking the count of nine.

Regarding the business negotiations which he had been conducting, he vouchsafed in jerks the information that the arrangements were practically completed. A few necessary formalities, and Norworth Court, in Hampshire, would be at the wanderers’ disposal. It was one of the show-places of England, he went on to explain—quite the stateliest pile in the county, and more to the same effect.

Della and her father were frankly dismayed at the prospect of such magnificence; but Mrs. Morrison rose to the occasion with indomitable courage.

Even Lord Arthur’s statement that Norworth was pronounced “Nooth” and had been the property of the baronets of that name since the reign of Queen Elizabeth failed to unnerve her.

After lunch his lordship found himself left alone with Mr. Morrison, and he turned to the subject which was uppermost in his mind. He did not suppose that Mr. Morrison was acquainted personally with Mr. Scobell, but he knew that the financier had had large interests in America, and Mr. Morrison, being a member of the staff of a bank, would probably be in a position to know the cause of the latter’s downfall.

“I wonder if you knew Mr. Benjamin Scobell, Mr. Morrison?” he said. “Very sad about him.”

“Hey?” said Mr. Morrison, nervously. He hated being left alone with Lord Arthur, of whom he stood in awe, and had been hoping to make a rapid retreat.

“Mr. Benjamin Scobell, the financier,” explained Lord Arthur. “I met his stepdaughter some time ago. A charming girl. It must have come as a great blow to her.”

“Great blow?” repeated the other, puzzled.

“I understood that he had become bankrupt.”

Mr. Morrison shook his head.

“Not old man Scobell. I know all about him. He banked with us. I guess you’re thinking of someone else. Old man Scobell’s no bankrupt. At least he wasn’t when I left New York. He kept a five-figure account with us, and it was still there when I quit. And I’d have heard of it if he had smashed since then. Why, if Scobell smashed there’d be a noise like as though the Singer Building had fallen on to a sheet of tin.”

Lord Arthur stared. He rose from the table in a state of utter bewilderment. If her stepfather was still a rich man, what conceivable reason could there be why Betty should be travelling as a paid companion with these Morrisons?

He dined at his club, and it was while he was sipping his coffee that his tired brain yielded a solution of the mystery, which, however fantastic, seemed to him the only one conceivable.

It was a trick! She was testing him! His faded eyes glowed with excitement as the thing seemed to piece itself together like the scattered sections of a child’s puzzle. It was, he told himself, precisely the scheme which a romantic girl would have devised. She was testing him. He had proposed to her when she was rich. Would she be the same in his eyes when she was a penniless girl, earning her own living? It was to decide that question that she had joined the Morrisons.

But he reflected she had made one miscalculation when she had assumed that he would not ascertain the truth concerning her stepfather’s financial status.

CHAPTER IX.

the meeting at the theatre.

After the first day London depressed Betty terribly.

The little party gathered under the banner of Mrs. Morrison at the Hotel Cecil dealt with the city each in his or her own way. To Della, though she had lived in it for some months, London was a strange city, and she and her mother set out to “do” the place with that grim thoroughness which is the peculiar property of a certain type of American visitor. Guide-book in hand, they swooped from spot to spot, devouring like locusts the Tower, London Bridge, St. Paul’s, the Zoo, the Crystal Palace, Kew Gardens, the Cheshire Cheese, and the rest, at the rate of two or three a day.

As for Betty, she passed what was probably the most miserable week of her life. The first excitement of her escape from Mervo was over, and her eyes were looking down the interminable vista of the years to come—a vista of drab greyness, without hope or joy to colour it. Della, resolutely determined to enjoy herself, professed to find quaintness where Betty found only squalor; hut even Della did not display any regret when Lord Arthur announced one morning that Mrs. Morrison’s “little place” was ready for its new tenants, and it was decided that the invaders should move to Hampshire on the following day.

Lord Arthur, during the week, had comported himself like a Galahad. When he exerted himself he could display a considerable charm of manner. He exerted himself now. He was playing for a big stake, and he spared no effort. Towards Betty his manner was such as recalled the old days of chivalry. His restrained devotion was admirable.

Betty was genuinely surprised. She had fancied that his lordship’s mind was an open book to her. And she had expected that her announcement that she was employed by Mrs. Morrison as a paid companion would have had a chilling effect on his ardour.

Her feelings began to alter. She was aching for friendship. She welcomed anything that would colour ever so slightly that grey vista down which she was looking. His lordship would have been vastly encouraged could he have guessed how high he stood in her estimation. He did not guess, for Betty, woman-like, felt more than she seemed to feel, and she struck his lordship at this early stage in the proceedings as regrettably unresponsive.

The opening performance of a new musical comedy was due on the party’s last night in London, and Mrs. Morrison had bought a box. Lord Arthur was to meet them at the theatre. The head of the family had decided to remain in slippered ease at the hotel. He had attended five theatrical performances during the week, and that, he held, was sufficient.

The musical comedy proved to be much like other musical comedies, of which Betty had seen two that week, and the first act had not been in progress long when her attention began to wander. She looked at the audience. The house was crowded. She ran her eye slowly over the stalls below.

And then suddenly her heart leaped, and she sank back quickly into the corner of the box, where the hanging curtain hid her. She had seen John.

He was sitting at the end of the ninth row, evidently in the company of the man seated next to him, a light-haired young man with glasses; for as Betty caught sight of him this young man bent across to make some remark.

She sat on in a dream. The figures on the other side of the footlights seemed blurred and far away. She felt as if she were choking. The sight of him had quickened into life a host of emotions which till then had been numbed.

She was conscious of a noise of clapping, and realized that the first act was over and that the curtain had fallen. Lord Arthur rose and went out to smoke a cigarette. She moved back farther into her corner, till her chair pressed against the wall.

Della turned to her with some question that she did not hear, and as she did so there was a knock at the door.

“May I come in?” said a voice in the doorway. “I caught sight of you at the end of the act, Della, and came round to see if you would still speak to your old friends.”

Della uttered a cry of surprise.

“Why, John Maude! Mother, this is Mr. Maude, whom I used to know in the office. John Maude, I want you to know my friend, Betty Brown.”

John had parted from Mr. Scobell on the quay at Mervo full of determination, but, as he discovered when he came to consider his plan of action, with only the vaguest ideas as to how he was to find the object of his search. As far as Paris the trail was broad and clear; but there, had it not been that Mr. Scobell had placed no limit on the expenses of the expedition, it might well have been lost altogether. Unhampered, however, by financial obstacles, John had been able to make exhaustive inquiries, which had led him to the Gare du Nord, and there the trail had become clear again. Among the scores of employés interviewed by John was the blue-bloused semaphore who had so harassed Della and her parents. From him John elicited the fact that the young lady had left the Gare du Nord in the Calais boat-train in the company of an American family of three—a father, a mother, and a daughter.

It was this clue that had brought John to London. He had engaged a room at the Savoy Hotel, and had spent his time wandering through the streets and dining and lunching at the most popular restaurants, in the hope of an accidental meeting.

Della had begun to speak again as Betty turned, and her breathless monologue served to bridge over what would otherwise have been a notable silence. Betty’s temples were throbbing. She was incapable of speech. And John stood in the doorway motionless. Him, too, the situation had deprived of words.

The orchestra had begun to tune up. All over the house people were returning to their seats. John muttered vaguely and opened the door. He was still dazed.

As the door closed Della jumped up and ran out into the corridor.

“Say, John Maude,” she said, rapidly, “I want to see a lot of you. I want all the old pals I can get around me these days. You’ve got to come down with us to our place in the country tomorrow. Will you? Promise!”

“Della,” said John, “you’re an angel. There’s nothing I’d like better in the world.”

“That’s a promise, then. I’ll fix it with ma. Well, I must be going back. Say, Betty’s a pretty girl, isn’t she? I want you two to be pals. She’s a dear. Oh, there’s the opening chorus. I must be getting back. Come around to the hotel to-morrow. And don’t you go side-stepping that castle proposition.”

“Mother,” said Della, at supper that night, “I’ve asked Mr. Maude to come down with us to stay at the Court to-morrow. He’s all alone here, and I guess he’s lonesome. That’s all right, ain’t it? Why, Betty, how pale you’re looking! What’s the matter? Ain’t you well?”

“I’m a little tired,” said Betty.

CHAPTER X.

norworth court.

Of the six members of the army of occupation which bivouacked round the tea-table on the upper terrace at Norworth Court two days later, Lord Arthur Hayling alone was completely contented and in tune with the peace of the summer evening.

To Della and her father the atmosphere of permanence was frightening. Norworth Court gave them the feeling of being becalmed in a Sargasso Sea from which there was no escape. Before Della’s eyes rose a vision of Tom Spiller—unattainable Tom—beckoning to her from across an impassable gulf. Across another gulf her father saw tall buildings and bustling street-cars.

Betty’s emotions were of a different order. Norworth Court did not affect her unpleasantly. In other circumstances she would have loved its old-world calm. But the thought that, postpone it as she might, sooner or later there must come that meeting alone with John killed her enjoyment. Wherever she looked, she seemed to meet his eyes, hurt and puzzled. A hundred times she had made up her mind to avoid the inevitable no longer, only to alter it at the last moment. She was afraid—afraid of him, afraid of herself; afraid of the pain which she must inflict and the pain which she must suffer.

To John the world had never seemed so bleak. Things had passed completely beyond his comprehension. Betty’s flight from Mervo had been only less intelligible than her avoidance of him now. His mind kept returning to that meeting in the Casino. Every detail of it stood out clearly in his memory. She had been friendly then. There were moments when he had almost persuaded himself that she had shown signs of being something more. Yet, now, she was making the most obvious efforts to avoid being alone with him for an instant. Time after time, in the brief period of this visit, she had done it. Sometimes Della was the unconscious buffer between them, but more frequently Lord Arthur.

John cast a furtive glance at his lordship as he sat contentedly sipping tea, and jealousy raged within him. Perhaps, suggested Jealousy, it was not merely to avoid being alone with him that Betty attached herself so closely to Lord Arthur.

This identical thought was occupying his lordship’s mind at that very moment, and to it was due his feeling of peace and that appreciation of the world and the summer evening. The plan of campaign which he had mapped out for himself appeared to be succeeding beyond his expectations. A little more, and the time would be ripe for that second attack which was to carry the position.

He finished his tea and lit a cigarette. It was the cool of the evening, and the surface of the little reed-fringed lake at the foot of the terraces glittered with the last rays of the setting sun. Mrs. Morrison had gone indoors, and her husband had pottered off to smoke a cigar. Della had just broken a long silence with a remark to John.

Lord Arthur turned to Betty, who was sitting between him and Della.

“Would you care to go out on the lake before the sun goes down, Miss Brown?” he said.

Betty looked round. John was talking to Della. It would put off the moment she was dreading for another day.

“Yes,” she said.

They had reached the second terrace before Della noticed them.

“Where are they going?” she said.

John did not reply. He was watching the pair as they made their way across the turf, absorbed in hard feelings towards his lordship.

“Gee,” said Della, “they’re going out in the punt. Shout to them. That punt-pole’s on the blink. I tried it yesterday, and it creaked. It’s cracked or something. He’ll go smashing it and falling in.”

“Will he?” said John, with grim satisfaction. “Do you object?”

Della looked at him quickly and laughed.

“Well,” she said, “now that you mention it, I guess I don’t. Say, John, how d’you like him?” She jerked her head towards the lake, where his lordship, wielding the suspected pole, was propelling the punt slowly across the water. “I don’t fall for him.” she went on, without waiting for an answer. “And the old gentleman don’t, either. His lordship’s like this place. He gives me cold feet. Does the place get you that way, too? Ever since I’ve been here I’ve been feeling as if I was some sort of a worm. Pa says the place makes him feel as if he was walking down Broadway in a straw hat in April.” She looked unhappily at the old grey walls of the house. “Kind of disapproving it looks, don’t it?”

John laughed. “You’ll get used to it.”

“Not in a million years. But between you and Betty I may manage to bear up. You’re both comforts. Gee, I wish Tom was here.” She rose. “I’ve got to go and write a letter,” she said, abruptly.

John remained where he was, his eyes fixed on the pair in the punt.

The sun had gone down behind the wood which topped the low hill beyond the lake, and twilight had stolen upon the world. The air was cool with falling dew. On the lake, Lord Arthur had turned the punt and was making for the shore.

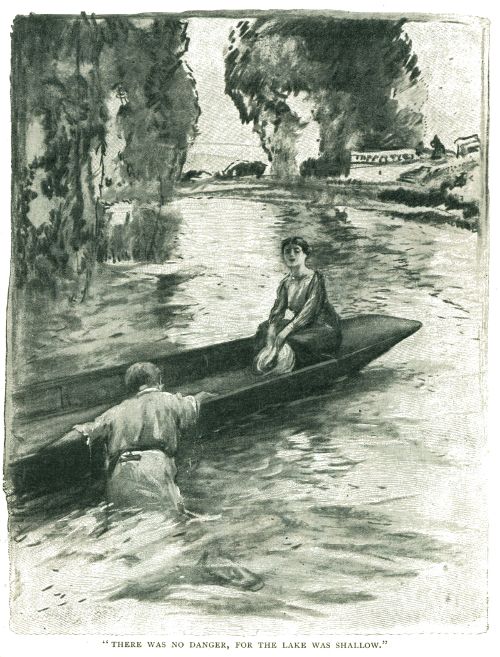

John rose from his chair and began to walk towards the house. He had hardly started when there came from the lake a cry and a splash. He wheeled quickly. The punt was rocking from side to side, and two feet from it, hatless and up to his waist in water, stood Lord Arthur, grasping a fragment of the pole. Della’s suspicions of its stability had been confirmed.

John ran easily towards the water’s edge. There was no danger, for the lake was shallow. He arrived as his lordship, towing the punt with one hand, waded ashore.

“The pole broke,” said his lordship, complainingly, clambering on to dry land.

John held the punt steady for Betty to get out.

“Lucky the water wasn’t deep,” he said. “You had better run up to the house and change your clothes. We’ll follow.”

Betty flushed.

“Oh——” she began, and stopped.

“I think I had better,” said his lordship, stepping out of his puddle and starting a fresh one.

He galloped moistly up the terrace. John watched for a moment, then turned to Betty. She had not moved.

For many days John had been scheming for just this moment, nerving himself for it, rehearsing the attitude that he would assume; but now that it had come he found himself unprepared. He was unequal to the situation. She was looking at him, her face cold and pale, and there was that in her look which set a chill wind blowing through the world and robbed him of speech.

A sense of being preposterously big obsessed him. He was conscious of his bulk as he had never been before. Subconsciously he felt that she was afraid of him, that she regarded him as something hostile. The thought was torture. He longed for words that would dispel it, but found none.

A nightmare feeling of unreality came upon him. How long had they been standing there? The departure of Lord Arthur was like some happening of the remote past. Æons seemed to have rolled by.

Suddenly Betty spoke.

“We shall he late,” she said, nervously.

John took a quick step towards her. Somehow the sound of her voice had broken the spell and set him free.

She shrank back as he moved; and he saw that there were tears in her eyes. A thrill went through him.

The next moment—the action was almost automatic—his fingers had touched her arm and closed on it.

She wrenched herself free.

“Betty!” he muttered.

They stood facing each other. He could hear her quick breathing. Her face was dim and indistinct, but her eyes shone in the darkness.

A strange weakness came upon John. He trembled. The contact of her soft flesh through the thin sleeve had set loose in him a whirl of primitive emotions.

“I love you!“ he said, in a low voice. Even to himself the words, as he spoke them, sounded bald and meaningless. To Betty, shaken by what had passed between her and Mr. Scobell, they sounded artificial, as if he were forcing himself to repeat a lesson. They jarred upon her.

“Don’t!” she said, sharply. “Oh, don’t!” Her voice stabbed him. “Don’t! I know. I’ve been told.”

She went on quickly, in gasps.

“I know all about it. My stepfather told me. He said—he said you were his”—she choked—”his hired man; that he paid you to stay and advertise the Casino. And he sent for me, and was going to tell you that—that you must marry me. Oh, it’s too horrible! That it should be you! You, who have been—you can’t understand what you have been to me—ever since we met. You couldn’t understand. I can’t tell you—a sort of help—something—something that—I can’t put it into words. Only it used to help me just to think of you. I didn’t mind if I never saw you again. I didn’t expect ever to see you again. It was just being able to think of you. It helped—you were something I could trust. Something strong—solid.” She laughed bitterly. “I suppose I made a hero of you. Girls are fools. But it helped me to feel that there was one man alive who—who put his honour above money.”

She broke off. John stood motionless, staring into the shadows. For the first time in his easy-going life he knew shame. The scales were falling from his eyes, though as yet he saw but dimly.

She began to speak again, in a low, monotonous voice, almost as if she were talking to herself. “I’m so tired of money—money—money. Everything’s money. Isn’t there a man in the world who won’t sell himself? I thought that you—— I suppose I’m stupid. One expects too much.”

She turned and went slowly up the terrace towards the house. Still he made no movement. A spell seemed to be on him. His eyes never left her. He could just see her white dress in the darkness. Once she stopped. With his whole soul he prayed that she would come back. But she moved on again, and was gone.

Then his brain cleared, and he began to think swiftly. He had begun to think with a curious coolness. It was one of those rare moments in a man’s life when, from the outside, through a breach in that wall of excuses and self-deception which he has been at such pains to build, he looks at himself impartially.

The sight that John saw through the wall was not comforting. It was not an heroic soul that, stripped of its defences, shivered beneath the scrutiny. In another mood he would have mended the breach, excusing and extenuating; but not now. He looked at himself without pity, and saw himself weak, slothful, devoid of all that was clean and fine, and a bitter contempt filled him.

From inside the house came the swelling note of the dinner-gong.

In his bedroom John’s mood of introspection gave way to one of restlessness. He must do something. He must show her that he was not the man she thought him. And then it came to him that there was only one way. If he was to prove that he was not the Casino’s hired man he must destroy the Casino. Not till he had done that could he face her again and say to her what he wished to say. He would prove to her that her first judgment of him had been the true one, that he was a man who could put his honour above money.

She loved him. She had not tried to hide it. He would show her that he was worthy of her love. He must return to Mervo at once. Every moment would be a year till he had made himself a free man.

Betty was not in the drawing-room when the gong sounded for dinner.

“Betty’s not feeling good,” explained Della. “She’s gotten a headache or a chill or something, poor kid. She was looking as pale as a sheet, so I made her go to bed.”

John went out on to the terrace after dinner. He felt more keenly than ever the imperative need for instant action. Would it be possible for him to leave to-night? If he could reach London early in the morning he would be able to catch the noon-day boat at Dover.

He threw away his cigar, and went back into the house to find a time-table. Yes, there was a slow train that would bring him to London in the small hours of the morning. He went up to his room, changed his clothes, and packed a bag. Then, walking warily by back-stairs, he stole out of the house and began his five-mile walk to the station.

Madame Eulalie’s Rare Plums

Madame Eulalie’s Rare Plums