The Strand Magazine, April 1912

CHAPTER XI.

an ultimatum from the throne.

HILE John, in the little steamer

from Marseilles, was nearing the end of his impulsive dash across Europe, Mr.

Scobell was breakfasting with his sister Marion in the morning-room of their

villa on the Mervo hillside.

HILE John, in the little steamer

from Marseilles, was nearing the end of his impulsive dash across Europe, Mr.

Scobell was breakfasting with his sister Marion in the morning-room of their

villa on the Mervo hillside.

A frown of displeasure furrowed Mr. Scobell’s brow.

“Marion,” he was saying, “who was the fellow with the Jewish name who made an automaton and got into trouble all round through it? It’s on the tip of my tongue.”

“You mean Frankenstein, dear. He was the hero of a novel by Mrs. Shelley. According to the story——”

“All right, all right,” interrupted her brother, rudely. “I know all that. I only wanted to remember the name. Well, I’m Frankenstein, and this Prince is the monster.”

“I don’t know why you should say that, Bennie,” protested his sister. “I’m sure he’s a very nice young man.”

“He’s such a nice young man,” said Mr. Scobell, “that I’d feel much easier in my mind if I had him tied to a tree by a string, instead of having let him go off all alone to wander around with money enough to buy suppers for all the chorus-girls in London for about ten years.”

Miss Scobell murmured something, which, fortunately, the financier did not hear, about boys being boys.

“People are beginning to ask questions,” went on Mr. Scobell. “Old d’Orby didn’t dare make a fuss when I worked the abolition of the Republic, but he didn’t like it. He wants to be President again, and he’s beginning to get the people stirred up. They’re getting ready to start trouble. If the Prince doesn’t come back soon and take off his coat and show them that he’s there, it’ll be the end of him, that’s all.”

He smoked his cigar-stump fiercely.

“I’m sure——” began Miss Scobell, when the door opened and a footman appeared.

“His Highness the Prince of Mervo desires to speak to you, sir. He is walking up and down the road before the villa, sir. He declined to enter. He said that he desired to see you alone, sir.”

“All right,” said Mr. Scobell. The footman retired. He turned to his sister. “There,” he said. “You see! Guilty conscience! Daren’t come in. He’s come to the end of his money, and is wondering how he can touch me for more. By George, I’ll talk to him!”

“Don’t be too hard on him, Bennie. He’s very young.”

“He won’t feel young by the time I’ve finished,” said Mr. Scobell, truculently. “He’ll feel about a million.”

During the past forty-eight hours John had had the maximum of mental unrest and the minimum of sleep. His eyes were red and his chin covered with a day’s stubble. His clothes were creased and wrinkled. In other words, he looked like a young man who had just completed the concluding exercises of a prolonged debauch, and Mr. Scobell, coming face to face with him, saw in his appearance the confirmation of his worst suspicions.

“So you’ve come back!” he growled.

John stopped.

“I wanted to see you,” he said.

“Wanted to see me? I bet you wanted to see me. Where have you been? Why isn’t Betty with you?”

John flushed.

“We won’t discuss that, if you don’t mind,” he said.

Mr. Scobell gasped for utterance.

“Won’t——?” he stammered. “Well, I’m hanged! Won’t discuss it!”

He gulped. Then he found connected speech. “Well!” he cried. “Here, you and I have got to have a talk, young man! You were to find Betty and bring her back and marry her, weren’t you? Well, why haven’t you done it?”

John stared. Understanding was coming slowly to him.

“I fixed this thing up,” continued Mr. Scobell, “and it’s got to go through. I fetched Betty over here to marry you, and she’s got to marry you. I explained the whole thing to her, but, being a fool girl, she tried to get out of it. But she’s got to come back, and I was chump enough to think that, when you went away, you meant to find her and fetch her back. Instead of which you go running loose all over London with my money, and——”

John cut through his explanations with a sudden sharp cry. A blinding blaze of understanding had flashed upon him. He understood everything now. Every word that Betty had spoken, every gesture that she had made, had become amazingly clear.

Suddenly his mind began to work quietly and coolly. He looked at the heated financier.

“Wait!” he said, and Mr. Scobell stopped in mid-sentence. “I found Miss Silver,” he went on.

“You found her?” The wrath died out of Mr. Scobell’s face. “Good boy! Forget anything I may have said in the heat of the moment, Prince! I thought you’d been on the toot in London. So you found her?”

“Yes. And she told me some of the things you said to her about me. They opened my eyes. Until I heard them I had not quite understood my position. I do now. You said that I was your employé.”

“It wasn’t intended for you to hear,” said Mr. Scobell, handsomely, “and Betty shouldn’t have handed it to you. I don’t wonder you feel hurt.”

“Don’t apologize. You were quite right. I was a fool not to see it before. You might have added that I was nothing more than a decoy for a gambling-hell.”

“Oh, come, Prince!” He felt in his vest-pocket. “Have a good cigar,” he said.

John waved aside the olive-branch.

“I object to being your employé,” he said. “And I object to being a decoy for a gambling-hell.”

“Why——”

“And I’m going to clear you out of this place, Mr. Scobell.”

“Eh? What? What’s that?”

John met his astonished eye coolly.

“There’s going to be a cleaning-up,” he said. “There will be no more gambling in Mervo.”

“You’re crazy,” gasped Mr. Scobell. “Abolish gambling? You can’t.”

“I can. That concession of yours isn’t worth the paper it’s written on. The Republic gave it to you. The Republic’s finished. If you want to conduct a Casino in Mervo, there’s only one man who can give you permission, and that’s myself. Do you understand?”

“But, Prince, talk sense.” Mr. Scobell’s voice was almost tearful. “It’s you who don’t understand. Do, for goodness’ sake, come down to earth and talk sense. Do you know how long you’d stay Prince of this place if you started to play the fool with my Casino? Just about long enough to let you pack a collar-stud and a tooth-brush into your portmanteau. And after that there wouldn’t be any more Prince.”

John shrugged his shoulders.

“I’ve said all I have to say. You’ve had your notice to leave. After to-day the Casino is closed.”

“But I tell you the people won’t stand it.”

“That’s for them to decide. They may have some self-respect.”

“They’ll turn you out.”

“Very well. That will prove that they have not.”

“But——”

John strode off down the road. He had been out of sight for several minutes before the financier recovered full possession of his faculties.

In after years John was wont to look back with amusement on the revolution which ejected him from the throne of his ancestors. But at the time its mirthfulness did not appeal to him. He was in frenzy of restlessness. Mervo had become a prison. But he must stay in it till the Casino business should be settled.

Presently there came a note from Mr. Scobell. It was brief. “Be sensible,” it ran. John tore it up.

It was on the same evening that definite hostilities may be said to have begun.

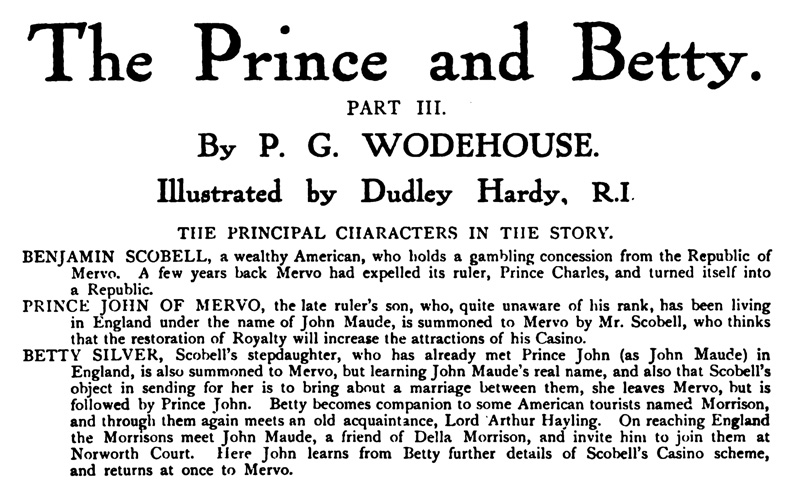

Between the palace and the market-place there was a narrow street of flagged stone, which was busy during the early part of the day, but deserted after sundown. Along this street, at about seven o’clock, John was strolling with a cigarette, when he was aware of a man crouching, with his back towards him.

So absorbed was the man in something which he was writing on the stones that he did not hear John’s approach, and the latter, coming up from behind, was enabled to see over his shoulder. In large letters of chalk he read the words, “Conspuez le Prince.’’

John’s knowledge of French was not profound, but he could understand this, and it annoyed him.

As he looked, the man, squatting on his heels, bent forward.

John had been a footballer before he was a Prince. The temptation was too much for him. He drew back his foot.

There was a howl and a thud, and John resumed his stroll. The first gun had been fired.

Early next morning a window at the rear of the palace was broken by a stone, and towards noon one of the soldiers on guard in front of the Casino was narrowly missed by an anonymous orange. For Mervo this was practically equivalent to the attack on the Bastille, and John, when the report of the atrocities was brought to him, became hopeful.

After breakfast on the following morning Mr. Crump paid a visit to the palace.

He was the bearer of another note from Mr. Scobell. This time John tore it up unread, and, turning to the secretary, invited him to sit down and make himself at home.

Sipping a whisky and soda and smoking one of John’s cigars, Mr. Crump became confidential.

“This is a queer business,” he said. “Old Ben is chewing pieces out of the furniture up there. He’s pretty well fed up. He’s losing money all the while the people are making up their minds about this thing, and it beats him why they’re so slow.”

“It beats me, too. I don’t believe these hook-worm victims ever turned my father out. Or, if they did, somebody must have injected radium into them first. I’ll give them another couple of days, and—— Halloa! What’s this?”

He rose to his feet as the sound of agitated voices came from the other side of the door. The next moment it flew open, revealing General Poineau and an assorted group of footmen and other domestics.

General Poineau rushed forward into the room, and flung his arms above his head.

“Mon prince!” he moaned.

A perfect avalanche of French burst from the group outside the door.

“Crump!” cried John. “Stand by me, Crump! Look alive! This is where you come out strong. Never mind the chorus gentlemen in the passage. Concentrate yourself on old General Dingbat.”

The General had begun to speak rapidly, with a wealth of gestures. It astonished John that Mr. Crump could follow the harangue as apparently he did.

Mr. Crump looked grave.

“He says there is a large mob in the marketplace. They are talking of moving in force on the palace. The Palace Guards have gone over to the people. General Poineau urges you to disguise yourself and escape while there is time. You will be safe at his villa till the excitement subsides, when you can be smuggled over to France to-night.”

“Not for me,” said John, shaking his head. It’s very good of you, General, and I appreciate it, but I can’t wait till night. The boat leaves for Marseilles in another hour. I catch that. I’ll go up and pack my bag.”

But as he left the room there came through the open window the mutter of a crowd. He stopped. General Poineau whipped out his sword and brought it to the salute. John patted him on the shoulder.

“You’re a stout fellow, General,” he said, “but we sha’n’t want it. Come along, Crump, and help me address the multitude.”

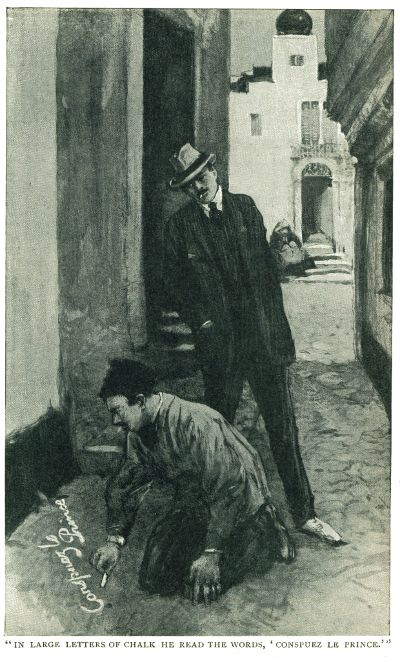

The window of the room looked out on to a square. There was a small balcony with a stone parapet. As John stepped out a howl of rage burst from the mob.

John walked on to the balcony and stood looking down on them, resting his arms on the parapet. The howl was repeated, and from somewhere at the back of the crowd came the sharp crack of a rifle, and a shot—the first and last of the campaign—clipped a strip of flannel from the collar of his coat.

John beckoned to Crump, who came on to the balcony with some reluctance, being mistrustful of the unseen sportsman.

“Tell ’em it’s all right, Crump, and that there’s no need for any fuss. From their manner I gather that I am no longer wanted on this throne. Ask them if that’s right.”

A small man, who appeared to be in command of the crowd, stepped forward as the secretary finished speaking and shouted some words which drew a murmur of approval from his followers.

“He wants to know,” interrupted Mr. Crump, “if you will allow the Casino to open again.”

“Tell him no, but add that I shall be delighted to abdicate, if that’s what they want. Bustle them, old man. Tell them to make up their minds quick, because I want to catch that boat.”

There was a moment’s surprised silence when Mr. Crump had spoken. The Mervian mind was unused to being hustled in this way. Then a voice shouted, as it were tentatively, “Vive la République!” and at once the cry was taken up on all sides.

John beamed down on them.

“That’s right,” he said. “Fine! But I shall be missing the boat. Will you tell them, Crump, that any citizen who cares for a drink and a cigar will find it in the palace? Tell the household staff to stand by to pull corks. It’s dry work revolutionizing. And now I really must be going. Give one of those fellows down there half a crown and send him to fetch a cab. I must rush.”

Five minutes later the revolutionists. obviously embarrassed and ill at ease, were sheepishly gulping down their refreshment beneath the stony eye of the major-domo and his assistants, while upstairs in the state bedroom the deposed Prince was packing the Royal pyjamas into his suit-case.

CHAPTER XII.

john returns to norworth.

In moments of emotion man has an unfortunate tendency to forget the conventionalities, especially if he be a man of John’s temperament. John’s mind, when he left Norworth Court, had been so full of the idea that he must go back to Mervo and abolish the gaming tables there that there had been no room in it for the realization of what was due to his host and hostess. And he had nearly completed his return journey before he began to consider his position. When he did so it was borne in upon him with some vividness that he had fallen a little short in the performance of those courtesies which etiquette demands of the departing guest.

He regretted his absent-mindedness. By the time he reached London he perceived quite clearly that, unless Mr. and Mrs. Morrison happened to be of an angelically forgiving disposition, Norworth Court was barred to him, and his chances of again meeting Betty remote.

Della seemed to him his one hope. Her friendship would probably have remained intact even under the trying conditions. He determined to take up a position at the village inn and see her before attempting anything else.

Accordingly, having arrived at the village, he sent off a messenger to her with a note; and presently he saw her approaching briskly, her face one note of interrogation.

“I’ll explain everything later,” he said, in answer to her rush of inquiries. “First, how do I stand—with your father and mother, I mean?”

“You’re in mighty bad with ma. Say, why did you want to rush off——”

“Della,” interrupted John, “I’ve just got to get into that house. I’ve got to see Betty. I’ve something to tell her. I must see her. Della, be a pal, as you always have been. Smuggle me into the house and see that I have five minutes with Betty alone.”

Della regarded him open-eyed.

“Are you in love with Betty, John Maude?”

“Of course I am.”

“Well, I guess you know your own business,” said Della, doubtfully. “But if I was a man in love with a girl, you wouldn’t catch me going off and leaving her alone with Lord Arthur to prowl around and——”

“What do you mean?” cried John.

“Well, I may be wrong, but the way it looks to me is that you aren’t the only rubber-plant in Brooklyn. I can’t understand it, though. I don’t see his lordship’s game. He’s out to marry for money, but—well, you ought to see him when Betty’s around. He’s Assiduous Willie all right.”

“Della, can you get me into the house this afternoon?”

Della considered. “I guess I could,” she said. “We’re giving our first garden-party this afternoon. His lordship has gathered in a bunch of his special pals. If we make good with them, as far as I can figure it, the rest of the swells in these parts will O.K. us and come flocking in. Everybody will be out helping to whoop things up in the garden, and you can just slip in. You know my little room next to the drawing-room? Sneak in there, and when I see a chance I’ll ask Betty to fetch something from the drawing-room. Then you can go in and talk to her. And all I say is, if you butt into trouble, keep me out of it.”

Under other conditions there might have been romance in John’s stealthy entry into Norworth Court that afternoon. He found himself in Della’s sitting-room, hot, uncomfortable, and with much the same emotions as he would have felt if he had managed to elude the conductor on a tramcar and escape paying his fare. Nothing could make such a situation romantic.

The room he was in was on the second floor. The window looked out on to the lake, and through it, as John stood there, came the sounds of aristocratic revels on the terrace below. Peeping cautiously round the curtain, he had a view of the select company which Lord Arthur Hayling had gathered together to mingle with the invaders. Tea was in progress. The terrace, dotted with summer frocks, presented a gay and animated appearance. So did Mrs. Morrison, seated in the centre of it; but John, watching her, doubted the genuineness of her gaiety. She was going through an ordeal such as she had never, he imagined, gone through before.

Official news from the front was brought, a few moments later, by Della. She looked cool and fresh in her light dress as she burst into the room, but her eyes were weary.

“I just came up to cry for a few minutes,” she announced, simply, sinking into a chair.

After a while she looked up, smiling contentedly.

“I’m all right now. I feel as if I’d had a Turkish bath.”

“What’s the matter?”

“Nothing. Just nerves. Why did we ever start this fool game? It’s all right for Betty. She’s used to mingling with this kind of bunch. Didn’t I always tell you so? She’s handling those duchesses and earls like an animal-tamer. Gee, I admire that kid!”

“And, talking of Betty——” suggested John.

“All right, I’ve not forgotten. I just looked in on my way to the drawing-room to leave my handkerchief on the piano. In about five minutes, when I’m too busy to leave the tea-table, I’ll ask Betty if she’d mind running up and——”

“Della, you’re a jewel. Isn’t there anything I can do for you?”

“Sure. If I freeze to death out there, tell Tom I died thinking of him. Good-bye.”

John resumed his watch from behind the curtain. He saw Della go out on the terrace and return to the tea-table. And then, for the first time, he distinguished Betty in the crowd below. She was talking to a woman in mauve. Close at hand hovered Lord Arthur Hayling.

John could follow all that went on, though no word reached him. Della, busy at the tea-table, spoke to Betty, who looked up at the drawing-room window and began to move towards the house.

She had reached the front door when Lord Arthur, detaching himself from the throng, moved off in the same direction. It might be that his lordship was going about some private business of his own, but in John’s mind there was no doubt that he was following Betty.

Voices became audible on the stairs, and the two passed the door behind which John stood and went on into the drawing-room. John opened the door cautiously and listened.

The drawing-room door was ajar, and in the silence of the house his lordship’s voice was plainly audible, apparently delivering a monologue. A single word gave John the clue, and then all that had been mysterious grew clear. In that cool drawing-room, not twelve feet from where he stood, his lordship was offering Betty his hand and title.

He clung to the door-handle. In the drawing-room the monologue proceeded on its rhythmical way.

In moments of emotion, it has been pointed out, John had a certain bias towards the impetuous. He was a little apt to treat any situation that had in it the elements of delicacy and embarrassment as if it were the enemy’s line in a football match.

Getting swiftly off the mark, he covered the distance to the drawing-room in three rapid bounds, and burst in.

When John, full of admirable resolutions, had set out under cover of the night to put an end to gambling in Mervo, his abrupt departure had not only offended his hostess, but had been entirely misinterpreted by Betty. She had regarded it as a sign on his part that, if there had ever been any struggle in his mind between wealth and self-respect, he had decided it in favour of the former.

The silent devotion of Lord Arthur Hayling, at first a trial, became gradually, as the days went by, something of a consolation. She was lonely to her very soul, and he was a friend. He was sympathetic. He could talk well. He had seen much of the world, and conveyed the idea of having read widely. Talking with him, she could check the pain that was always with her.

Sometimes a sudden and vivid memory of John would sweep over her mind, and she would see clearly the impossibility of what she contemplated; but the thought would return, and she would weaken once more.

It was in one of these moods of weakness that Lord Arthur had found her as she was setting out in quest of Della’s handkerchief. His lordship’s practised eye perceived it, and he knew that the moment was ripe for which he had been preparing, when he should put into words what till now had been mere hints.

He felt no trepidation. Words of the kind he intended to speak were his specialty. He was no raw novice at proposing marriage. He did it often, and he did it well.

He embarked gracefully on his declaration. Words proceeded from him in an easy, musical flow.

And then, at the very climax of his speech, the door flew open, revealing John. Lord Arthur stared at the intruder dumbly.

Betty rose to her feet, white and startled.

“Betty!” said John.

He stopped, and in the pause his lordship found speech.

“What—what the devil——? What the devil are you doing here?”

“I want to speak to you, Betty,” said John. His lordship did not move. His immobility maddened John.

“Get out,” he said, tersely.

Still his lordship made no movement. And John gave way to that impetuosity to which he was such a victim. He sprang forward and picked his lordship up in his arms.

The window of the drawing-room, like most of the windows at Norworth Court, was broad and massive and set well back in the thick wall, leaving outside a ledge some two feet in width. At present it was open, to allow the evening breeze to cool the room. The sight inspired John. He moved towards it.

Betty uttered a little cry of horror. For a moment the thing had taken on the aspect of tragedy.

John’s designs, however, were not homicidal. Holding his lordship, now in a sitting position on the ledge, he reached up a hand, and began to draw down the heavy sash.

“I shouldn’t struggle,” he advised. “You won’t fall. At least, you’ll have to get out of your coat to do it,” he added.

And, pulling the tails of his lordship’s coat into the room, he wedged the sash down tightly upon them.

From outside the window, curiously muffled, came the voice of his lordship, raising itself in a general appeal for help.

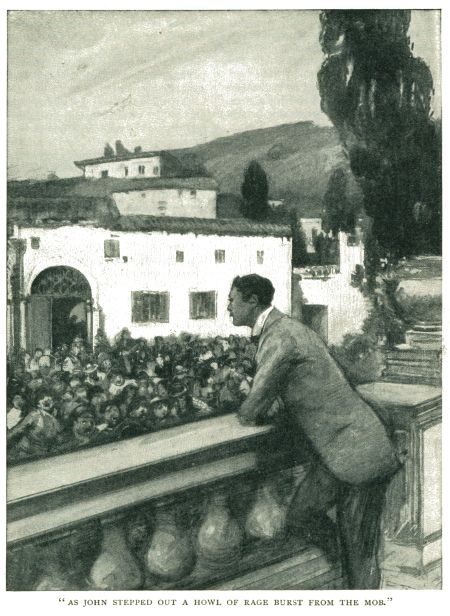

John crossed to the door and locked it. Then he turned to Betty. She did not move as he approached her.

“They’ll be coming in a moment,” he said, “so I must talk quick. Betty, I’ve come back to explain. All those things you said to me that night were true. But there was one thing you thought of me then, though you didn’t say it, which wasn’t true. I may have been a steerer for a gambling-hell, but I wasn’t that!”

He stopped.

“I had no suspicion.” he went on. “Perhaps I ought to have seen, but I didn’t. It never occurred to me. When I followed you from Mervo I hadn’t a notion what was wrong. Then you told me, and I saw. I had never thought of my position in that way before. But I knew you were right, and I knew I couldn’t see you again till I had squared myself. I went straight back to Mervo, and there I saw your stepfather, and he told me—what he had told you. . . . And then I shut down the Casino.”

Betty looked at him without speaking. Her heart was beating quickly. As yet she did not fully comprehend.

“I abolished the gaming tables,” he went on. Then she understood, and she trembled with the sudden rush of happiness that filled her.

She made an impulsive movement towards him. She was conscious of a passionate longing to feel his arms round her.

She could not speak, but there was no need for words. She saw his face light up. And then he had gathered her into his arms and was holding her there, clutching her to him fiercely. Her own about his neck tightened convulsively, forcing his head down until his face rested against hers.

She raised a small, cool hand to his face and gently stroked his cheek. She performed it almost unconsciously, this half-formal gesture with which woman, from the days of Eve, has taken possession of the man she loves.

“I want you,” she said.

She pressed more closely against his arms. They were strong arms, restful to lean against at the journey’s end.

CHAPTER XIII.

the last straw.

Meanwhile the sudden appearance of Lord Arthur Hayling on a second-storey window-sill had had a marked effect on the dignified revellers on the terrace. His frantic demands for help disposed of the idea that he had assumed the position for his own amusement, and the phenomenon occasioned, in consequence, considerable mystification.

But Mrs. Morrison’s guests quickly recovered their poise. The well-bred Briton has two methods of coping with the unusual, and if one fails the other is always successful. His first step, when faced with any situation that promises to be embarrassing, is to ignore it. If it will not be ignored, he simply goes away.

The guests at the garden-party adopted the latter method. The air became full of polite farewells.

The advance-guard of the rescue party, which had arrived almost immediately after his lordship had been sighted, consisted of Della, Mr. Briggs, the butler, and Henry, one of the footmen.

At first Della had had that leaden sense of irretrievable disaster which oppresses the soul when matters have passed out of our hands and are running amok.

She did not blame John. In the same circumstances she would have wished her Tom to behave in the same way. But that did not alter the fact that he had completely spoiled the party. The polite self-effacement of the guests was merely temporary. When they had gone they would discuss the matter. It would be talked about at fifty dinner-tables. The story would permeate the county like an epidemic. And that the victim should have been Lord Arthur Hayling was the final tragedy.

Mr. Briggs, the butler, was hammering experimentally on one panel of the door.

There came the sound of the key turning in the lock. The door opened, and John appeared.

“John Maude,” cried Della, “what, in the name of goodness, have you been doing? What’s his lordship——?”

“By George! I’d completely forgotten him! Della,” he said, ruefully, “I’m awfully sorry this should have happened.”

“You aren’t the only one! Aren’t you going to pull him in?”

“I suppose I’d better.”

John turned to the window.

There are moments in life too poignant for speech. Such a moment occurred when John, raising the sash, pulled Lord Arthur off his perch and deposited him on the drawing-room carpet. It was a situation to which no words could have done justice, and his lordship did not attempt any. Under considerable disadvantages, for his face was red and his clothes soiled, he maintained an impressive dignity. Ignoring John, who had begun in friendly fashion to dust him down, he stood, stiffly erect, pulling his moustache.

It was one of those situations to which it seems at first sight impossible to add any further touch of embarrassment. This, however, Della contrived to do.

His lordship had not observed her presence for a moment, but now, catching sight of her, he turned sharply, and prepared to speak. Such, however, was the overwrought state of his mind that he hesitated, marshalling his thoughts, for an instant. And it was in that instant that Della did the unforgivable thing. She laughed!

Lord Arthur started; and then, with a stiff bow, he walked abruptly out of the room.

“Oh, Della!” said Betty.

Della leaned against the piano, giggling helplessly.

“I didn’t mean to! I couldn’t help it! Honest, I didn’t mean to!”

She dried her eyes.

“I guess that’s put the lid on it,” she said. “It’s too bad of me! Making that kind of a break! Oh, well!”

Further sounds of movement came from the passage outside. Mr. and Mrs. Morrison entered. There was a strained look on the latter’s face. She sank down in a chair and covered her eyes with her hands.

Della crossed quickly to her side and put an arm affectionately round her.

“We met his lordship on the stairs,” explained Mr. Morrison, briefly. “He’s madder than a hornet. He’s beaten it. Never coming back.”

Della gave her mother a remorseful hug. Mrs. Morrison was sobbing quietly. She put out a hand and patted Della’s arm.

“Yes, honey. I know it’s hard on you. I know how disappointed you’ll be. I’d go on if I could, but I can’t. I’ve tried and tried not to hate it, but I can’t help it. It’s killing me. I can’t stand it. I knew I couldn’t the moment the folks began to arrive for this party, and when I saw Lord Arthur s-sitting on the w-w-window——”

Della sprang to her feet.

“Ma! Do you mean to say you want to quit—to go back to America?”

Mrs. Morrison nodded miserably.

“I know it’s a disappointment for you, honey, but——”

She broke off. Della had flung herself upon her and was hugging her rapturously.

“You dear! You darling!” she cried.

Mr. Morrison had begun to execute a species of dance. He revolved slowly, snapping his fingers and uttering weird cries. And Betty and John, skirting round him, passed unnoticed from the room.

CHAPTER XIV.

conclusion.

On the following day John wrote to Mr. Scobell, informing him of his engagement to Betty. It was a curt letter, and contained no suggestion that the writer regarded the financier’s approval or disapproval as in any way affecting the matter in hand.

An era of the deepest peace had now set in at Norworth Court. Lord Arthur was in London at his club. The servants had left in a body, as requested on the day after the garden-party, and the little band of survivors were living, with vast content, a picnic life, supporting themselves, when they did not go to the village inn, on meals cooked by Mrs. Morrison.

It was a peaceful, happy time. With the departure of the guests the depressing spell of the Court seemed to have vanished.

Mrs. Morrison, relieved of the burden of her social duties, had become a different woman. And Della was radiant. She had broken the facts in the case of Tom to her parents during the first moments of the revolution, and Mr. Morrison, having pointed out the various ways in which the American young man was superior to every other known variety of young man, had given his approval without a murmur of dissent.

John and Betty spent the days wandering about the grounds or exploring the little lake in the punt, for which another pole had been provided in place of that which had broken.

Betty, happy though she was in the present, was inclined to touch on the future more frequently than John liked. His views were unvaryingly optimistic.

“Leave it to me,” he said. “I’ve got about thirty pounds. What more do we want? Rockefeller and all those fellows started with about twopence. We’ll go to America with the Morrisons. I’ll get a job of some sort, if it’s blacking boots.”

But Fate had arranged a different destiny for him. Towards the end of the week he was strolling back along the main street of the village, whither he had been to buy tobacco, when from a window on the ground floor of the inn a voice spoke.

“Hey!” said the voice of Mr. Scobell.

John had wondered sometimes what Mr. Scobell’s move would be on receipt of his letter. He had been a little surprised at not hearing from him. That he would come to Norworth he had not anticipated.

“Come along in, Prince,” said Mr. Scobell, smiling amiably. “I want to have a talk with you.”

John found the financier seated amidst the remains of a late breakfast, smiling benignly and plainly resolved to let bygones be bygones.

“First,” he began, “about you and Betty. Go right ahead. I’ve no objection.”

“That’s very good of you,” said John. “I thought that, after what had happened——”

“Oh, pshaw!” interrupted the other. “That’s all a thing of the past. There’s no hard feelings about that. Why, Prince, do you know that fool game of yours, stopping the tables and all that, was the best thing that could possibly have happened? If we’d tried for a million years we couldn’t have thought of a better advertisement. The tables are booming. Why, if it goes on like this, we shall have to hang out the Standing Room Only signs.”

John laughed.

“Well, if the world’s so full of fools,” he said, “I don’t see why you shouldn’t have your share of them. So long as I’m not mixed up in it, you can do all the business you please.”

Mr. Scobell regarded him curiously.

“Prince,” he said, leaning forward, “you’ve got no fixed ideas about what you’re going to do from now on, have you?”

“I’ve thought of one or two things. Blacking boots was the last. But I’ve settled nothing.”

“Good! Then this is where we talk business. Did you ever hear the story of the fellows who were making a bet and the fellow who offered to hold the money, and then they wanted to know who was going to hold him?”

“When I was a baby I kicked my nurse for telling me that story.”

“Well, it’s that way with me. You know I’ve got a heap of interests over in America? Well, I’ve got a heap of fellows watching those interests for me. What I want now is someone to watch those fellows. See what I mean? I want someone honest, someone I can trust. He needn’t be a financial genius; all he wants to be is honest, and I’m going to offer the job to you. And I’ll pay you well.”

“What?” said John. “You’re going to do that?”

He drew in his breath slowly.

“This sounds pretty good to me,” he added.

“It’s yours if you’ll take it.”

John leaned across the table and extended his hand.

“I will,” he said. “And thanks for saving my life. I never did think much of that bootblack scheme.”

He sat back and looked at Mr. Scobell.

“What you’ve done with your wings and harp, I can’t think,” he said, meditatively. “It’s a wonderful disguise.”

John and Betty were married quietly—or as quietly as the village organist, a lusty performer, would permit—two weeks later at Norworth Church. The bride was given away by Mr. Scobell, who, with a delicacy of feeling of which few who knew him would have deemed him capable, refrained from smoking during the ceremony. The wedding breakfast was held at the Court, after which the newly-married pair set off in a motor-car, the gift of the bride’s stepfather, for their honeymoon tour.

It was while the chauffeur was cranking up the machine that Mr. Benjamin Scobell exhibited the only trace of sentiment with which history credits him.

Betty was already in the car, and John, buttoning his motor-coat, was about to follow her, when the financier drew him aside.

“Hi!” he said. “Jest a moment, Prince.”

John bent an attentive ear.

“Prince,” said Mr. Scobell, puffing earnestly at his cigar and keeping his eyes fixed on the distant hills. “I’ve got something I want you to do for me.”

“Yes?” said John. “What’s that?”

Mr. Scobell continued to inspect the distant hills.

“I wish you’d name him Benjamin,” he said, softly.

“Him?” said John, puzzled. “Who? . . . Great Scot!”

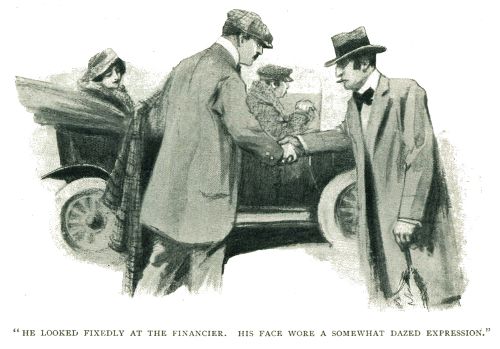

He looked fixedly at the financier. His face wore a somewhat dazed expression.

“The papers call you Hustler Scobell, don’t they?” he said, at last.

Mr. Scobell blushed with pleasure.

“Why, yes. That’s so. They do.”

John nodded thoughtfully.

“I don’t wonder,” he said. “I don’t wonder. Good-bye.”

the end.

Madame Eulalie’s Rare Plums

Madame Eulalie’s Rare Plums