The Strand Magazine, June 1927

THE young man with the fresh, ingenuous face turned from the smoking-room window, through which he had been gazing out upon the smiling links.

“Nice day, sir,” he said.

The Oldest Member looked up with a start. He eyed the young man with a pleased surprise, gratified to find one of the younger generation of his own volition engaging him in conversation. For of late he had noticed on the part of his juniors a tendency to flit rapidly past him with vague mutterings.

“A beautiful day,” he agreed. “You are a new member here, I think?”

“Just joined. It’s a great course.”

“None better.”

“They give you a good lunch, too.”

“Capital.”

“In fact, the only drawback to the club, the secretary tells me, is that there is a fearful old bore who hangs about the place, lying in wait to collar people and tell them stories.”

The Oldest Member wrinkled his forehead thoughtfully.

“I do not know whom he can have been referring to,” he said. “No, I cannot recall any such person. But, talking of stories, you will be interested in the one I am about to relate. It is the story of John Gooch, Frederick Pilcher, Sidney McMurdo, and Agnes Flack.”

A wordless exclamation proceeded from the young man. His fresh face had lost some of its colour. He looked wistfully at the door.

“John Gooch, Frederick Pilcher, Sidney McMurdo, and Agnes Flack,” repeated the Oldest Member, firmly.

You may have noticed (said the Oldest Member) how frequently it happens that practitioners of the Arts are quiet, timid little men, shy in company and unable to express themselves except through the medium of the pencil or the pen. John Gooch was like that. So was Frederick Pilcher. Gooch was a writer and Pilcher was an artist, and they used to meet a good deal at the house of Agnes Flack, where they were constant callers. And every time they met John Gooch would say to himself, as he watched the other balancing a cup of tea and smiling his weak, propitiatory smile, “I am fond of Pilcher, but his best friend could not deny that he is a pretty dumb brick.” And Pilcher, as he saw Gooch sitting on the edge of his chair and fingering his tie, would reflect, “Nice fellow as Gooch is, he is certainly a total loss in mixed society.”

Mark you, if ever men had an excuse for being ill at ease in the presence of the opposite sex, these two had. They were both eighteen-handicap men, and Agnes Flack was exuberantly and dynamically scratch. She stood about five feet ten in her stockings, and had shoulders and fore-arms which would have excited the envy and admiration of one of those muscular women who good-naturedly allow six brothers, three sisters, and a cousin by marriage to pile themselves on her collar-bone while the orchestra plays a long-drawn chord and the audience streams out to the bar. Her eye resembled the eye of one of the more imperious queens of history; and when she laughed strong men clutched at their temples to keep the tops of their heads from breaking loose.

Even Sidney McMurdo was as a piece of damp blotting-paper in her presence. And he was a man who weighed two hundred and eleven pounds and had once been a semi-finalist in the Amateur Championship. He loved Agnes Flack with an ox-like devotion. And yet—and this will show you what life is—when she laughed, it was nearly always at him. I am told by those in a position to know that, on the occasion when he first proposed to her—on the sixth green—distant rumblings of her mirth were plainly heard in the club-house locker-room, causing two men who were afraid of thunderstorms to scratch their match.

Such, then, was Agnes Flack. Such, also, was Sidney McMurdo. And such, while we are on the subject, were Frederick Pilcher and John Gooch.

Now John Gooch, though, of course, they had exchanged a word from time to time, was in no sense an intimate of Sidney McMurdo. It was consequently a surprise to him when one night, as he sat polishing up the rough draft of a detective story—for his was a talent that found expression largely in blood, shots in the night, and millionaires who are found murdered in locked rooms with no possible means of access except a window forty feet above the ground—the vast bulk of McMurdo lumbered across his threshold and deposited itself in a chair.

The chair creaked. Gooch stared. McMurdo groaned.

“Are you ill?” said John Gooch.

“Ha!” said Sidney McMurdo.

He had been sitting with his face buried in his hands, but now he looked up; and there was a red glare in his eyes which sent a thrill of horror through John Gooch. The visitor reminded him of the Human Gorilla in his novel, “The Mystery of the Severed Ear.”

“For two pins,” said Sidney McMurdo, displaying a more mercenary spirit than the Human Gorilla, who had required no cash compensation for his crimes, “I would tear you into shreds.”

“Me?” said John Gooch, blankly.

“Yes, you. And that fellow Pilcher, too.” He rose; and, striding to the mantelpiece, broke off a corner of it and crumbled it in his fingers. “You have stolen her from me.”

“Stolen? Whom?”

“My Agnes.”

John Gooch stared at him, thoroughly bewildered. The idea of stealing Agnes Flack was rather like the notion of sneaking off with the Albert Hall. He could make nothing of it.

“She is going to marry you.”

“What!” cried John Gooch, aghast.

“Either you or Pilcher.” McMurdo paused. “Shall I tear you into little strips and tread you into the carpet?” he murmured, meditatively.

“No,” said John Gooch. His mind was blurred, but he was clear on that point.

“Why did you come butting in?” groaned Sidney McMurdo, absently taking up the poker and tying it into a lover’s knot. “I was getting along splendidly until you two pimples broke out. Slowly but surely I was teaching her to love me, and now it can never be. I have a message for you. From her. I proposed to her for the eleventh time to-night; and when she had finished laughing she told me that she could never marry a mere mass of brawn. She said she wanted brain. And she told me to tell you and the pest Pilcher that she had watched you closely and realized that you both loved her, but were too shy to speak, and that she understood and would marry one of you.”

THERE was a long silence.

“Pilcher is a splendid fellow,” said John Gooch. “She must marry Pilcher.”

“She will, if he wins the match.”

“What match?”

“The golf match. She read a story in a magazine the other day where two men played a match at golf to decide which was to win the heroine; and about a week later she read another story in another magazine where two men played a match at golf to decide which was to win the heroine. And a couple of days ago she read three more stories in three more magazines where exactly the same thing happened; and she has decided to accept it as an omen. So you and the hound Pilcher are to play eighteen holes, and the winner marries Agnes.”

“The winner?”

“Certainly.”

“I should have thought—I forget what I was going to say.”

McMurdo eyed him keenly.

“You have not been trifling with this girl’s affections, Gooch, I hope?”

“No, no. Oh, no.”

“Because, if I thought that, I should know what steps to take. Even now——” He paused, and looked at the poker in his hand in a rather yearning sort of way. “No, no,” he said, “better not, better not.” With a gesture of resignation he flung the thing down. “Good night, weed. The match will be played on Friday morning. And may the better—or, rather, the less impossibly foul—man win.”

He banged the door, and John Gooch was alone.

But not for long. Scarcely half an hour had passed when the door opened once more, to admit Frederick Pilcher. The artist’s face was pale, and he was breathing heavily. He sat down, and after a brief interval contrived to summon up a smile. He rose and patted John Gooch on the shoulder.

“John,” he said, “I am a man who as a general rule hides his feelings. I mask my affections. But I want to say, straight out, here and now, that I like you, John.”

“Yes?” said John Gooch.

Frederick Pilcher patted his other shoulder.

“I like you so much, John, old man, that I can read your thoughts, strive to conceal them though you may. I have been watching you closely of late, John, and I know your secret. You love Agnes Flack.”

“I don’t!”

“Yes, you do. Ah, John, John,” said Frederick Pilcher, with a gentle smile, “why try to deceive an old friend? You love her, John. You love that girl. And I have good news for you, John—tidings of great joy. I happen to know that she will look favourably on your suit. Go in and win, my boy, go in and win. Take my advice and dash round and propose without a moment’s delay.”

John Gooch shook his head. He, too, smiled a gentle smile.

“Frederick,” he said, “this is like you. Noble. That’s what I call it. Noble. It’s the sort of thing the hero does in act two. But it must not be, Frederick. It must not, shall not be. I also can read a friend’s heart, and I know that you, too, love Agnes Flack. And I yield my claim. I am excessively fond of you, Frederick, and I give her up to you. God bless you, old fellow. God, in fact, bless both of you.”

“Look here,” said Frederick Pilcher, “have you been having a visit from Sidney McMurdo?”

“He did drop in for a minute.”

There was a tense pause.

“What I can’t understand,” said Frederick Pilcher, at length, peevishly, “is why, if you don’t love this infernal girl, you kept calling at her house practically every night and sitting goggling at her with obvious devotion.”

“It wasn’t devotion.”

“It looked like it.”

“Well, it wasn’t. And, if it comes to that, why did you call on her practically every night and goggle just as much as I did?”

“I had a very good reason,” said Frederick Pilcher. “I was studying her face. I am planning a series of humorous drawings on the lines of Felix the Cat, and I wanted her as a model. To goggle at a girl in the interests of one’s Art, as I did, is a very different thing from goggling wantonly at her like you.”

“Is that so?” said John Gooch. “Well, let me tell you that I wasn’t goggling wantonly. I was studying her psychology for a series of stories which I am preparing, entitled ‘Madeline Monk, Murderess.’ ”

Frederick Pilcher held out his hand.

“I wronged you, John,” he said. “However, be that as it may, the point is that we both appear to be up against it very hard. An extraordinarily well-developed man, that fellow McMurdo.”

“A mass of muscle.”

“And of a violent disposition.”

“Dangerously so.”

Frederick Pilcher drew out his handkerchief and dabbed at his forehead.

“You don’t think, John, that you might ultimately come to love Agnes Flack?”

“I do not.”

“Love frequently comes after marriage, I believe.”

“So does suicide.”

“Then it looks to me,” said Frederick Pilcher, “as if one of us was for it. I see no way out of playing that match.”

“Nor I.”

“The growing tendency on the part of the modern girl to read trashy magazine stories,” said Frederick Pilcher, severely, “is one that I deplore. I view it with alarm. And I wish to goodness that you authors wouldn’t write tales about men who play golf matches for the hand of a woman.”

“Authors must live,” said John Gooch. “How is your game these days, Frederick?”

“Improved, unfortunately. I am putting better.”

“I am steadier off the tee.” John Gooch laughed bitterly. “When I think of the hours of practice I have put in, little knowing that a thing of this sort was in store for me, I appreciate the irony of life. If I had not bought Sandy McHoots’ book last spring, I might now be in a position to be beaten five and four.”

“Instead of which, you will probably win the match on the twelfth.”

John Gooch started.

“You can’t be as bad as that!”

“I shall be on Friday.”

“You mean to say you aren’t going to try?”

“I do.”

“You have sunk to such depths that you would deliberately play below your proper form?”

“I have.”

“Pilcher,” said John Gooch, coldly, “you are a hound, and I never liked you from the start.”

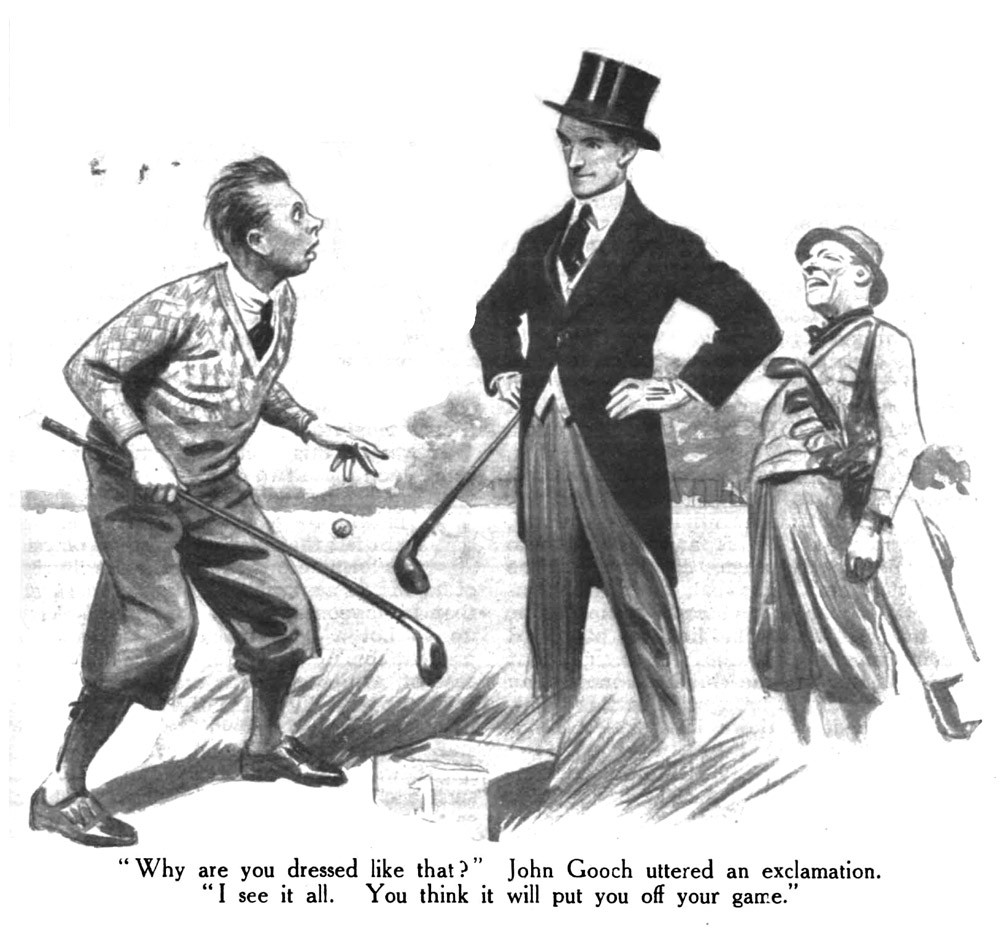

YOU would have thought that, after the conversation which I have just related, no depth of low cunning on the part of Frederick Pilcher would have had the power to surprise John Gooch. And yet, as he saw the other come out of the club-house to join him on the first tee on the Friday morning, I am not exaggerating when I say that he was stunned.

John Gooch had arrived at the links early, wishing to get in a little practice. One of his outstanding defects as a golfer was a pronounced slice; and it seemed to him that, if he drove off a few balls before the match began, he might be able to analyse this slice and see just what was the best stance to take up in order that it might have full scope. He was teeing his third ball when Frederick Pilcher appeared.

“What—what—what——!” gasped John Gooch.

For Frederick Pilcher, discarding the baggy, mustard-coloured plus-fours in which it was his usual custom to infest the links, was dressed in a perfectly-fitting morning-coat, yellow waistcoat, striped trousers, spats, and patent-leather shoes. He wore a high stiff collar, and on his head was the glossiest top-hat ever seen off the Stock Exchange. He looked intensely uncomfortable; and yet there was on his face a smirk which he made no attempt to conceal.

“What’s the matter?” he asked.

“Why are you dressed like that?” John Gooch uttered an exclamation. “I see it all. You think it will put you off your game.”

“Some idea of the kind did occur to me,” replied Frederick Pilcher, airily.

“You fiend!”

“Tut tut, John. These are hard words to use to a friend.”

“You are no friend of mine.”

“A pity,” said Frederick Pilcher, “for I was hoping that you would ask me to be your best man at the wedding.” He took a club from his bag and swung it. “Amazing what a difference clothes make. You would hardly believe how this coat cramps the shoulders. I feel as if I were a sardine trying to wriggle in its tin.”

The world seemed to swim before John Gooch’s eyes. Then the mist cleared, and he fixed Frederick Pilcher with a hypnotic gaze.

“You are going to play well,” he said, speaking very slowly and distinctly. “You are going to play well. You are going to play well. You——”

“Stop it!” cried Frederick Pilcher.

“You are going to play well. You are going——”

A heavy hand descended on his shoulder. Sidney McMurdo was regarding him with a black scowl.

“We don’t want any of your confounded chivalry,” said Sidney McMurdo. “This match is going to be played in the strictest spirit of—— What the devil are you dressed like that for?” he demanded, wheeling on Frederick Pilcher.

“I—I have to go into the City immediately after the match,” said Pilcher. “I sha’n’t have time to change.”

“H’m. Well, it’s your own affair. Come along,” said Sidney McMurdo, gritting his teeth. “I’ve been told to referee this match, and I don’t want to stay here all day. Toss for the honour, worms.”

John Gpoch spun a coin. Frederick Pilcher called tails. The coin fell heads up.

“Drive off, reptile,” said Sidney McMurdo.

As John Gooch addressed his ball, he was aware of a strange sensation which he could not immediately analyse. It was only when, after waggling two or three times, he started to draw his club back that it flashed upon him that this strange sensation was confidence. For the first time in his life he seemed to have no doubt that the ball, well and truly struck, would travel sweetly down the middle of the fairway. And then the hideous truth dawned on him. His subconscious self had totally misunderstood the purport of his recent remarks and had got the whole thing nicely muddled up.

Much has been written of the subconscious self, and all that has been written goes to show that of all the thick-headed, blundering chumps who take everything they hear literally, it is the worst. Anybody of any intelligence would have realized that when John Gooch said, “You are going to play well,” he was speaking to Frederick Pilcher; but his subconscious self had missed the point completely. It had heard John Gooch say, “You are going to play well,” and it was seeing that he did so.

The unfortunate man did what he could. Realizing what had happened, he tried with a despairing jerk to throw his swing out of gear just as the club came above his shoulder. It was a fatal move. You may recall that when Arnaud Massy won the British Open Championship one of the features of his play was a sort of wiggly twiggle at the top of the swing, which seemed to have the effect of adding yards to his drive. This wiggly twiggle John Gooch, in his effort to wreck his shot, achieved to a nicety. The ball soared over the bunker in which he had hoped to waste at least three strokes; and fell so near the green that it was plain that only a miracle could save him from getting a four.

There was a sardonic smile on Frederick Pilcher’s face as he stepped on to the tee. In a few moments he would be one down, and it would not be his fault if he failed to maintain the advantage. He drew back the head of his club. His coat, cut by a fashionable tailor who, like all fashionable tailors, resented it if the clothes he made permitted his customers to breathe, was so tight that he could not get the club-head more than half-way up. He brought it to this point, then brought it down in a lifeless semi-circle.

“Nice!” said Sidney McMurdo, involuntarily. He despised and disliked Frederick Pilcher, but he was a golfer. And a golfer cannot refrain from giving a good shot its meed of praise.

For the ball, instead of trickling down the hill as Frederick Pilcher had expected, was singing through the air like a shell. It fell near John Gooch’s ball and, bounding past it, ran on to the green.

The explanation was, of course, simple. Frederick Pilcher was a man who, in his normal golfing costume, habitually overswung. This fault the tightness of his coat had now rendered impossible. And his other pet failing, the raising of the head, had been checked by the fact that he was wearing a top-hat. It had been Pilcher’s intention to jerk his head till his spine cracked; but the unseen influence of generations of ancestors who had devoted the whole of their intellect to the balancing of top-hats on windy days was too much for him.

A MINUTE later the two men had halved the hole in four.

The next hole, the water-hole, they halved in three. The third, long and over the hill, they halved in five.

And it was as they moved to the fourth tee that a sort of madness came upon both Frederick Pilcher and John Gooch simultaneously.

These two, you must remember, were eighteen-handicap men. That is to say, they thought well of themselves if they could get sixes on the first, sevens on the third, and anything from fours to elevens on the second—according to the number of balls they sank in the water. And they had done these three holes in twelve. John Gooch looked at Frederick Pilcher and Frederick Pilcher looked at John Gooch. Their eyes were gleaming, and they breathed a little stertorously through their noses.

“Pretty work,” said John Gooch.

“Nice stuff,” said Frederick Pilcher.

“Get a move on, blisters,” growled Sidney McMurdo.

It was at this point that the madness came upon these two men.

PICTURE to yourself their position. Each felt that by continuing to play in this form he was running a deadly risk of having to marry Agnes Flack. Each felt that his opponent could not possibly keep up so hot a pace much longer, and the prudent course, therefore, was for himself to ease off a bit before the crash came. And each, though fully aware of all this, felt that he was dashed if he wasn’t going to have a stab at doing the round of his life. It might well be that, having started off at such a clip, he would find himself finishing somewhere in the eighties. And that, surely, would compensate for everything.

After all, felt John Gooch, suppose he did marry Agnes Flack, what of it? He had faith in his star, and it seemed to him that she might quite easily get run over by a truck or fall off a cliff during the honeymoon. Besides, with all the facilities for divorce which modern civilization so beneficently provides, what was there to be afraid of in marriage, even with an Agnes Flack?

Frederick Pilcher’s thoughts were equally optimistic. Agnes Flack, he reflected, was undeniably a pot of poison; but so much the better. Just the wife to keep an artist up to the mark. Hitherto he had had a tendency to be a little lazy. He had avoided his studio and loafed about the house. Married to Agnes Flack, his studio would see a lot more of him. He would spend all day in it—probably have a truckle bed put in and never leave it at all. A sensible man, felt Frederick Pilcher, can always make a success of marriage if he goes about it in the right spirit.

John Gooch’s eyes gleamed. Frederic! Pilcher’s jaw protruded. And neck and neck, fighting grimly for their sixes and sometimes even achieving fives, they came to the ninth green, halved the hole, and were all square at the turn.

It was at this point that they perceived Agnes Flack standing on the club-house terrace.

“Yoo-hoo!” cried Agnes in a voice of thunder.

And John Gooch and Frederick Pilcher stopped dead in their tracks, blinking like abruptly-awakened somnambulists.

She made a singularly impressive picture, standing there with her tweed-clad form outlined against the white of the club-house wall. She had the appearance of one who is about to play Boadicea in a pageant; and John Gooch, as he gazed at her, was conscious of a chill that ran right down his back and oozed out at the soles of his feet.

“How’s the match coming along?” she yelled, cheerily.

“All square,” replied Sidney McMurdo, with a sullen scowl. “Wait where you are for a minute, germs,” he said. “I wish to have a word with Miss Flack.”

He drew Agnes aside and began to speak to her in a low rumbling voice. And presently it was made apparent to all within a radius of half a mile that he had been proposing to her once again, for suddenly she threw her head back and there went reverberating over the countryside that old familiar laugh.

“Ha, ha, ha, ha, ha, ha, HA!” laughed Agnes Flack.

John Gooch shot a glance at his opponent. The artist, pale to the lips, was removing his coat and hat and handing them to his caddie. And, even as John Gooch looked, he unfastened his braces and tied them round his waist. It was plain that from now on Frederick Pilcher intended to run no risk of not overswinging.

John Gooch could appreciate his feelings. The thought of how that laugh would sound across the bacon and eggs on a rainy Monday morning turned the marrow in his spine to ice and curdled every red corpuscle in his veins. Gone was the exhilarating ferment which had caused him to skip like a young ram when a long putt had given him a forty-six for the first nine. How bitterly he regretted now those raking drives, those crisp flicks of the mashie-niblick of which he had been so proud ten minutes ago. If only he had not played such an infernally good game going out, he reflected, he might at this moment be eight or nine down and without a care in the world.

A shadow fell between him and the sun; and he turned to see Sidney McMurdo standing by his side, glaring with a singular intensity.

“Bah!” said Sidney McMurdo, having regarded him in silence for some moments.

He turned on his heel and made for the club-house.

“Where are you going, Sidney?” asked Agnes Flack.

“I am going home,” replied Sidney McMurdo, “before I murder these two miserable harvest-bugs. I am only flesh and blood, and the temptation to grind them into powder and scatter them to the four winds will shortly become too strong. Good morning.”

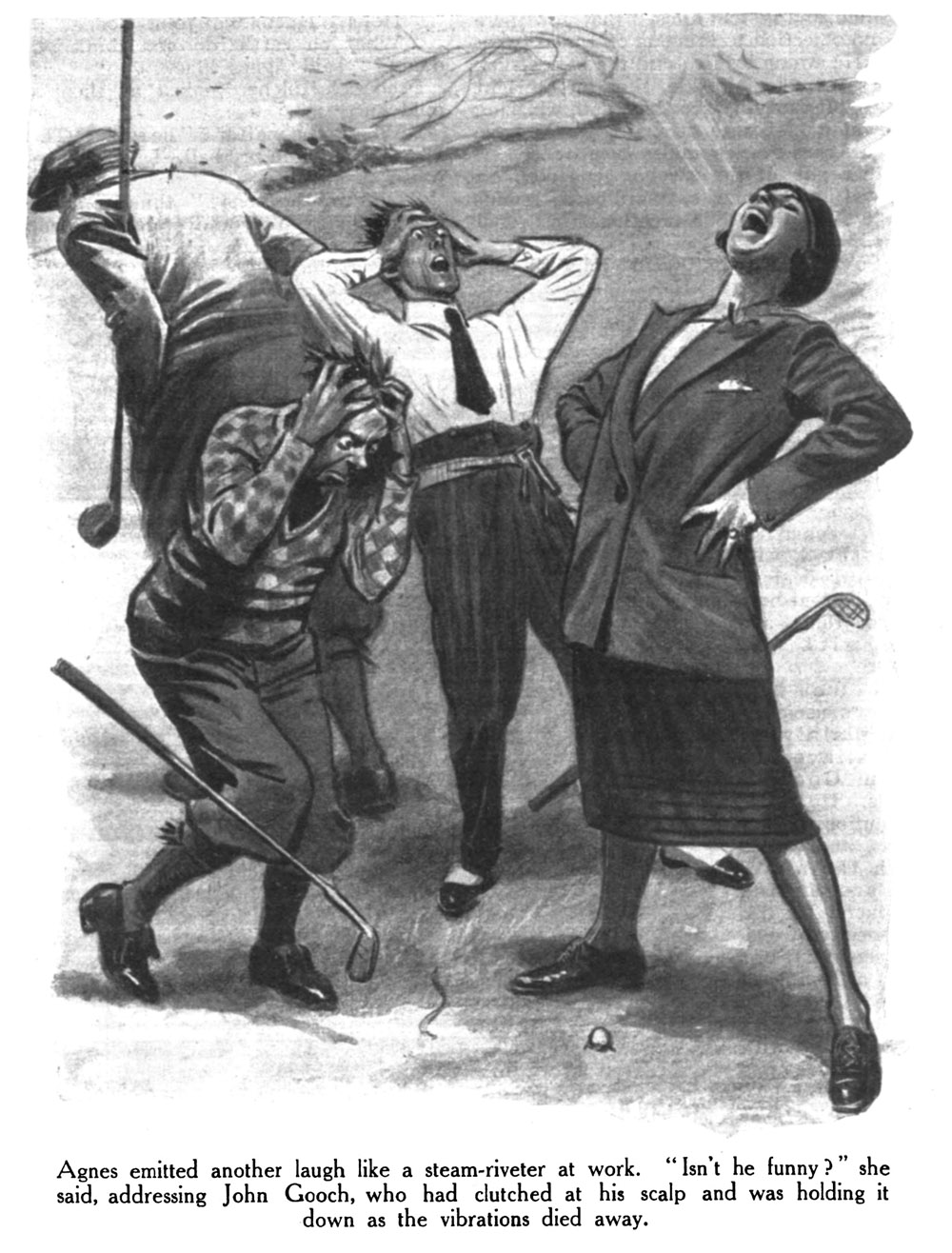

Agnes emitted another laugh like a steam-riveter at work.

“Isn’t he funny?” she said, addressing John Gooch, who had clutched at his scalp and was holding it down as the vibrations died away. “Well, I suppose I shall have to referee the rest of the match myself. Whose honour? Yours? Then drive off and let’s get at it.”

THE demoralizing effects of his form on the first nine holes had not completely left John Gooch. He drove long and straight, and stepped back appalled. Only a similar blunder on the part of his opponent could undo the damage.

But Frederick Pilcher had his wits well about him. He overswung as he had never overswung before. His ball shot off into the long grass on the right of the course, and he uttered a pleased cry.

“Lost ball, I fancy,” he said. “Too bad!”

“I marked it,” said John Gooch, grimly. “I will come and help you find it.”

“Don’t trouble.”

“It is no trouble.”

“But it’s your hole, anyway. It will take me three or four to get out of there.”

“It will take me four or five to get a yard from where I am.”

“Gooch,” said Frederick Pilcher, in a cautious whisper, “you are a cad.”

“Pilcher,” said John Gooch, in tones equally hushed, “you are a low bounder. And if I find you kicking that ball under a bush, there will be blood shed—and in large quantities.”

“Ha, ha!”

“Ha, ha to you!” said John Gooch.

The ball was lying in a leathery tuft, and, as Pilcher had predicted, it took three strokes to move it back to the fairway. By the time Frederick Pilcher had reached the spot where John Gooch’s drive had finished, he had played seven.

But there was good stuff in John Gooch. It is often in times of great peril that the artistic temperament shows up best. Missing the ball altogether with his next three swings, he topped it with his fourth, topped it again with his fifth, and, playing the like, sent a low, skimming shot well over the green into the bunker beyond. Frederick Pilcher, aiming for the same bunker, sliced and landed on the green. The six strokes which it took John Gooch to get out of the sand decided the issue. Frederick Pilcher was one up at the tenth.

BUT John Gooch’s advantage was short-lived. On the right, as you approach the eleventh green, there is a deep chasm, spanned by a wooden bridge. Frederick Pilcher, playing twelve, just failed to put his ball into this, and it rolled on to within a few feet of the hole. It seemed to John Gooch that the day was his. An easy mashie-shot would take him well into the chasm, from which no eighteen-handicap player had ever emerged within the memory of man. This would put him two down—a winning lead. He swung jubilantly, and brought off a nicely-lofted shot which seemed to be making for the very centre of the pit.

And so, indeed, it was; and it was this fact that undid John Gooch’s schemes. The ball, with all the rest of the chasm to choose from, capriciously decided to strike the one spot on the left-hand rail of the wooden bridge which would deflect it towards the flag. It bounded high in the air, fell on the green; and the next moment, while John Gooch stood watching with fallen jaw and starting eyes, it had trickled into the hole.

There was a throbbing silence. Then Agnes Flack spoke.

“Important, if true,” she said. “All square again. I will say one thing for you two—you make this game very interesting.”

And once more she sent the birds shooting out of the tree-tops with that hearty laugh of hers. John Gooch, coming slowly to after the shattering impact of it, found that he was clutching Frederick Pilcher’s arm. He flung it from him as if it had been a loathsome snake.

A grimmer struggle than that which took place over the next six holes has probably never been seen on any links. First one, then the other seemed to be about to lose the hole, but always a well-judged slice or a timely top enabled his opponent to rally. At the eighteenth tee the game was still square; and John Gooch, taking advantage of the fact that Agnes had stopped to tie her shoe-lace, endeavoured to appeal to his one-time friend’s better nature.

“Frederick,” he said, “this is not like you.”

“What isn’t like me?”

“Playing this low-down game. It is not like the old Frederick Pilcher.”

“Well, what sort of a game do you think you are playing?”

“A little below my usual, it is true,” admitted John Gooch. “But that is due to nervousness. You are deliberately trying to foozle, which is not only painting the lily but very dishonest. And I can’t see what motive you have, either.”

“You can’t, can’t you?”

John Gooch laid a hand persuasively on the other’s shoulder.

“Agnes Flack is a most delightful girl.”

“Who is?”

“Agnes Flack.”

“A delightful girl?”

“Most delightful.”

“Agnes Flack is a delightful girl?”

“Yes.”

“Oh?”

“She would make you very happy.”

“Who would?”

“Agnes Flack.”

“Make me happy?”

“Very happy.”

“Agnes Flack would make me happy?”

“Yes.”

“Oh?”

John Gooch was conscious of a slight discouragement. He did not seem to be making headway.

“Well, then, look here,” he said, “what we had better do is to have a gentleman’s agreement.”

“Who are the gentlemen?”

“You and I.”

“Oh?”

John Gooch did not like the other’s manner, nor did he like the tone of voice in which he had just spoken. But then there were so many things about Frederick Pilcher that he did not like that it seemed useless to try to do anything about it. Moreover, Agnes Flack had finished tying her shoe-lace, and was making for them across the turf like a mastodon striding over some prehistoric plain. It was no time for wasting words.

“A gentleman’s agreement to halve the match,” he said hurriedly.

“What’s the good of that? She would only make us play extra holes.”

“We would halve those, too.”

“Then we should have to play it off another day.”

“But before that we could leave the neighbourhood.”

“Sidney McMurdo would follow us to the ends of the earth.”

“Ah, but suppose we didn’t go there? Suppose we simply lay low in the city and grew beards?”

“There’s something in it,” said Frederick Pilcher, reflectively.

“You agree?”

“Very well.”

“Splendid!”

“What’s splendid?” asked Agnes Flack, thudding up.

“Oh—er—the match,” said John Gooch. “I was saying to Pilcher that this was a splendid match.”

Agnes Flack sniffed. She seemed quieter than she had been at the outset, as though something were on her mind.

“I’m glad you think so,” she said. “Do you two always play like this?”

“Oh, yes. Yes. This is about our usual form.”

“H’m! Well, push on.”

It was with a light heart that John Gooch addressed his ball for the last drive of the match. A great weight had been lifted from his mind, and he told himself that now there was no objection to bringing off a real sweet one. He swung lustily; and the ball, struck on its extreme left side, shot off at right angles, hit the ladies’ tee-box, and, whizzing back at a high rate of speed, would have mown Agnes Flack’s ankles from under her, had she not at the psychological moment skipped in a manner extraordinarily reminiscent of the high hills mentioned in Sacred Writ.

“Sorry, old man,” said John Gooch, hastily, flushing as he encountered Frederick Pilcher’s cold look of suspicion. “Frightfully sorry, Frederick, old man. Absolutely unintentional.”

“What are you apologizing to him for?” demanded Agnes Flack with a good deal of heat. It had been a near thing, and the girl was ruffled.

Frederick Pilcher’s suspicions had plainly not been allayed by John Gooch’s words. He drove a cautious thirty yards, and waited with the air of one suspending judgment for his opponent to play his second. It was with a feeling of relief that John Gooch, smiting vigorously with his brassie, was enabled to establish his bona fides with a shot that rolled to within mashie-niblick distance of the green.

Frederick Pilcher seemed satisfied that all was well. He played his second to the edge of the green. John Gooch ran his third up into the neighbourhood of the pin.

Frederick Pilcher stooped and picked his ball up.

“Here!” cried Agnes Flack.

“Hey!” ejaculated John Gooch.

“What on earth do you think you’re doing?” said Agnes Flack.

Frederick Pilcher looked at them with mild surprise.

“What’s the matter?” he said. “There’s a blob of mud on my ball. I just wanted to brush it off.”

“Oh, my heavens!” thundered Agnes Flack. “Haven’t you ever read the rules? You’re disqualified.”

“Disqualified?”

“Dis-jolly-well-qualified,” said Agnes Flack, her eyes flashing scorn. “This cripple here wins the match.”

Frederick Pilcher heaved a sigh.

“So be it,” he said. “So be it.”

“What do you mean, so be it? Of course it is.”

“Exactly. Exactly. I quite understand. I have lost the match. So be it.”

And, with drooping shoulders, Frederick Pilcher shuffled off in the direction of the bar.

John Gooch watched him go with a seething fury which for the moment robbed him of speech. He might, he told himself, have expected something like this. Frederick Pilcher, lost to every sense of good feeling and fair play, had double-crossed him. He shuddered as he realized how inky must be the hue of Frederick Pilcher’s soul; and he wished in a frenzy of regret that he had thought of picking his own ball up. Too late! Too late!

For an instant the world had been blotted out for John Gooch by a sort of red mist. This mist clearing, he now saw Agnes Flack standing looking at him in a speculative sort of way, an odd expression in her eyes. And beyond her, leaning darkly against the club-house wall, his bulging muscles swelling beneath his coat and his powerful fingers tearing to pieces what appeared to be a section of lead piping, stood Sidney McMurdo.

John Gooch did not hesitate. Although McMurdo was some distance away, he could see him quite clearly; and with equal clearness he could remember every detail of that recent interview with him. He drew a step nearer to Agnes Flack, and, having gulped once or twice, began to speak.

“Agnes,” he said, huskily, “there is something I want to say to you. Oh, Agnes, have you not guessed——”

“One moment,” said Agnes Flack. “If you’re trying to propose to me, sign off. There is nothing doing. The idea is all wet.”

“All wet?”

“All absolutely wet. I admit that there was a time when I toyed with the idea of marrying a man with brains, but there are limits. I wouldn’t marry a man who played golf as badly as you do if he were the last man in the world. Sid-nee!” she roared, turning and cupping her mouth with her hands; and a nervous golfer down by the lake-hole leaped three feet and got his mashie entangled between his legs.

“Hullo?”

“Hullo?”

“I’m going to marry you, after all.”

“Me?”

“Yes, you.”

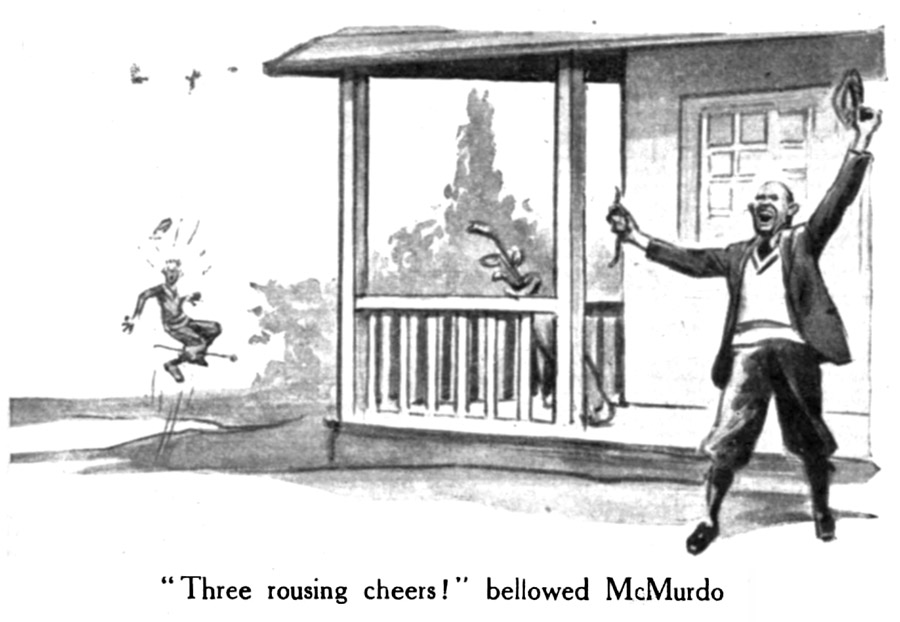

“Three rousing cheers!” bellowed McMurdo.

“Three rousing cheers!” bellowed McMurdo.

Agnes Flack turned to John Gooch. There was something like commiseration in her eyes, for she was a woman. Rather on the large side, but still a woman.

“I’m sorry,” she said.

“Don’t mention it,” said John Gooch.

“I hope this won’t ruin your life.”

“No, no.”

“You still have your Art.”

“Yes, I still have my Art.”

“Are you working on anything just now?” asked Agnes Flack.

“I’m starting a new story to-night,” said John Gooch. “It will be called ‘Saved From the Scaffold.’ ”

Madame Eulalie’s Rare Plums

Madame Eulalie’s Rare Plums