Vanity Fair, May 1916

DIARY OF A WAR-TIME HONEYMOON

of Irma Withers, Whose Husband

Refused to See America First

Honeymooners by FISH

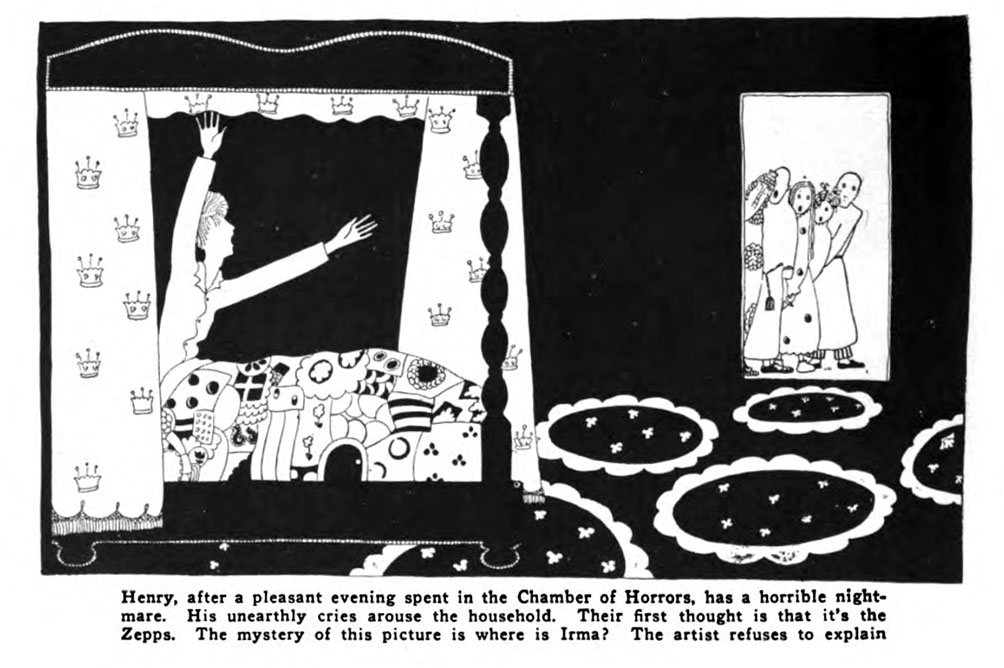

MONDAY. I feel sure this is going to be one of the most unpleasant honeymoons I have ever had. Henry would come to London. I told him that the War was bound to upset things, but he said that he was sick and tired of spending his honeymoons at Niagara Falls and that it would take more than a European War to keep him out of England. He is so obstinate and self-willed. I think he must be one of those cave-men you read about, or Abysmal Brutes, or whatever you call them. He insists on having his own way. So different from Horace and Theodore: and even Harold—though he could exhibit an iron will—never refused to yield to my wishes right at the beginning of the honeymoon. Yet, when I told Henry that I did not wish to spend the honeymoon in London, he said in the most brutal way that if I refused to come, he would go alone. “The war won’t have destroyed the great monuments of history, will it?” he said. “Me for the Morgue and Big Ben and Public Houses and the Crystal Palace, where the King lives.” So here we are, and I am sure I’ll hate it.

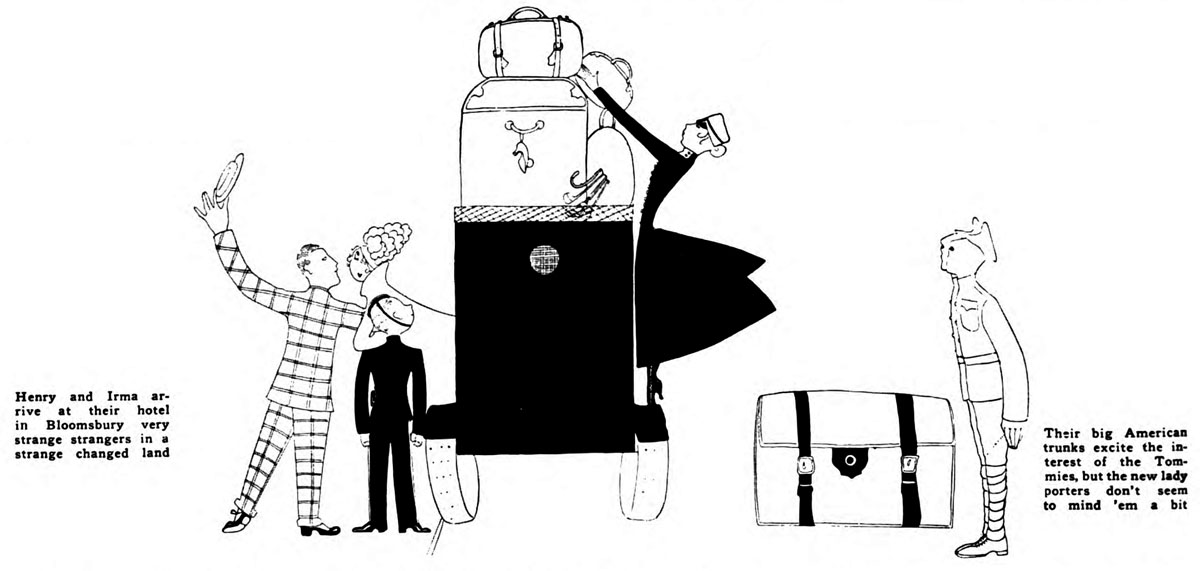

RIGHT from the start I began to feel uneasy. I had not realized that men were so scarce over here. A female ticket-clerk sold us our tickets at Liverpool: there were female porters at the London station: and a most dangerously attractive young person drove the taxi-cab to our hotel. I caught Henry winking at all of them, and his manner, as he gave the directions to our chauffeuse, was unnecessarily suave for one in his position. I began to feel that it might be difficult to induce Henry to keep his mind on his job. How different it all would have been in the pure air of Atlantic City.

TUESDAY. Is it wrong of me to feel a slight but well-defined thrill of happiness at the discovery that Henry, too, is having his troubles? We are staying at a hotel in Bloomsbury, and this morning the proprietor brought Henry a large sheet of questions to fill in. After all the trouble we had in getting our passports, I think they might have let us alone. Henry had got as far as “Born, Waupakoneta, Walla-Walla County, Wisconsin,—Father absent at the time, but Mother there—No Teutonity in family—Hired Girl a Swede—Mother a Methodist—Father nothing,” when he began to feel faint and asked the senile waiter—all the staff here are at least a hundred years old—to bring him a bottle of Pabst. The waiter gave a shudder. “It’s after two-thirty, sir,” he said, “and even if it wasn’t there’s a ’undred pound fine if you treated the lady.” Henry said—most brutally—that he had had no intention of treating the lady, and the waiter presented the anti-wine card. “We can do you a nice stone ginger-beer, sir, or a glass of barley-water. Or would you prefer a beaker of milk-and-soda?” Henry staggered out of the place, clucking like a wounded hen, and I did not see him again for the rest of the day. Can it be that I have been deceived in Henry? Is he the sort of man to whose care a young and trusting divorcée should have given her happiness? I am beginning to have forebodings. (Later, Henry has come back, complaining of being poisoned. It seems, from what I can make of his disjointed ramblings, that he spent the day lowering himself to the level of the beasts that perish by means of a beverage called Kopp’s Ale, discovering only after he had consumed several dozen that it was non-alcoholic. I feel sure that Henry is not all that I thought him to be.)

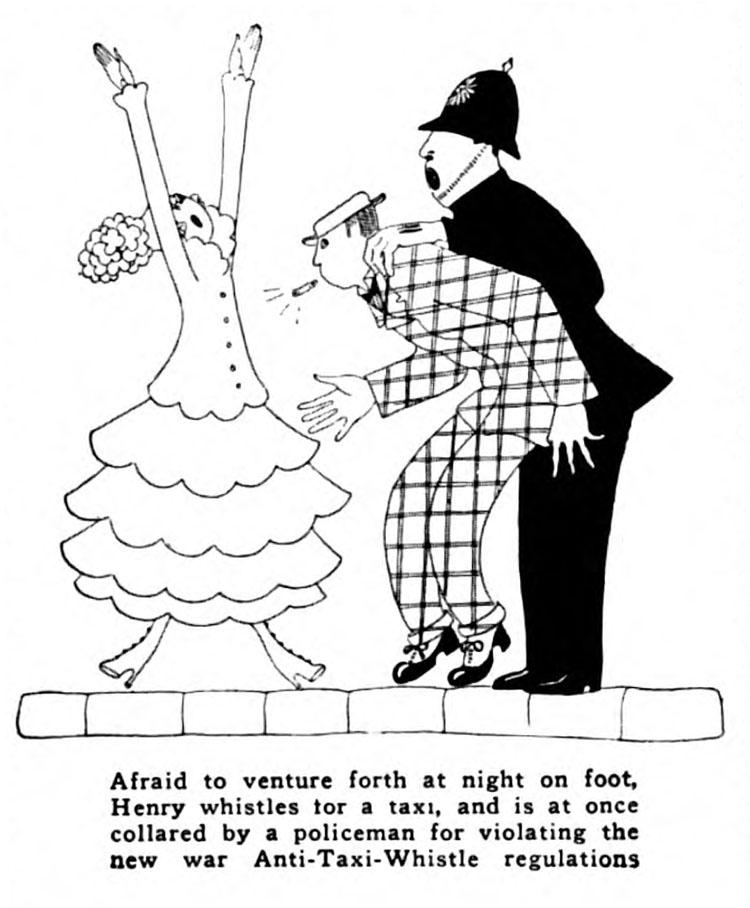

WEDNESDAY. There is no doubt about it. Henry’s fascination is beginning to wane. I managed to

drag him out to see the city’s objects of interest to-day. As I very justly said, now was the

time to improve our minds: after we had settled down to our married life it would be too late.

He showed a most indecent exultation on learning that the British Museum had been closed, and

wanted to go to the movies. But I was firm, and we made our way to Westminster Abbey. It was

while we were making for this wonderful edifice that Henry made the first of those mistakes

which, if persisted in, are certain to lead to our being arrested as spies and shot at sunrise

in the Tower. He said that he was tired of walking, and he pulled a whistle out of his pocket

and blew it for a taxi. The next moment a large policeman had him by the scruff of the neck and

was telling him to come quietly. It was only my repeated assertions that Henry was not

responsible for his actions and would never do it again that kept them from putting him in

prison on a charge of whistling to attract Zeppelins. Really, I do think I have been deceived

in Henry. An Abysmal Brute is bad enough, but an Abysmal Brute who is also an apparently

incurable bonehead is a combination which few wives have been called upon to love, honor, and

obey.

WEDNESDAY. There is no doubt about it. Henry’s fascination is beginning to wane. I managed to

drag him out to see the city’s objects of interest to-day. As I very justly said, now was the

time to improve our minds: after we had settled down to our married life it would be too late.

He showed a most indecent exultation on learning that the British Museum had been closed, and

wanted to go to the movies. But I was firm, and we made our way to Westminster Abbey. It was

while we were making for this wonderful edifice that Henry made the first of those mistakes

which, if persisted in, are certain to lead to our being arrested as spies and shot at sunrise

in the Tower. He said that he was tired of walking, and he pulled a whistle out of his pocket

and blew it for a taxi. The next moment a large policeman had him by the scruff of the neck and

was telling him to come quietly. It was only my repeated assertions that Henry was not

responsible for his actions and would never do it again that kept them from putting him in

prison on a charge of whistling to attract Zeppelins. Really, I do think I have been deceived

in Henry. An Abysmal Brute is bad enough, but an Abysmal Brute who is also an apparently

incurable bonehead is a combination which few wives have been called upon to love, honor, and

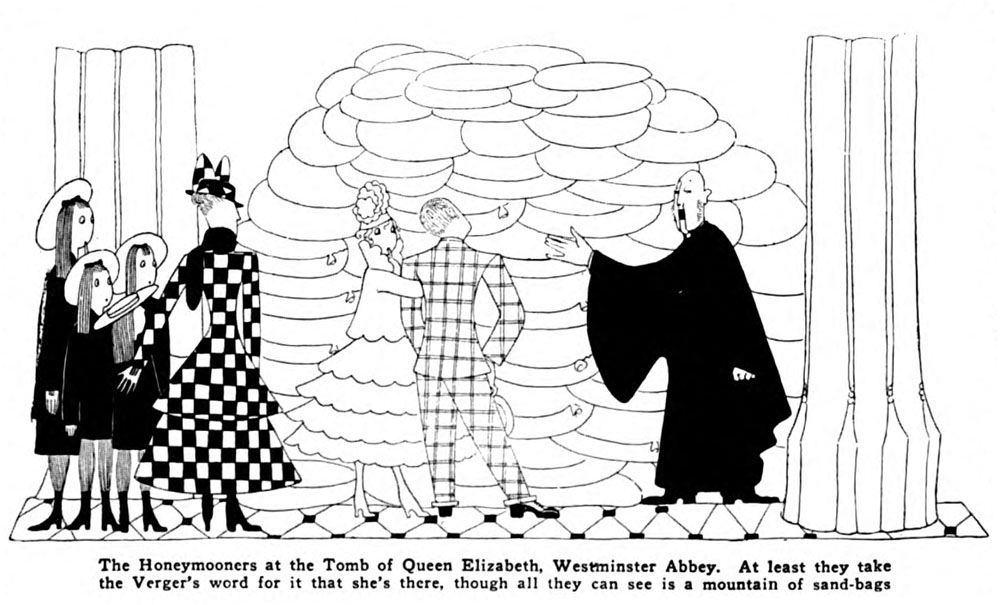

obey.  When we got to Westminster Abbey, we spent a fascinating hour gazing at the slabs

beneath which lie England’s mighty dead and on top of which lie the sandbags placed there in

case of bombs. “There,” I said to Henry in a hushed whisper, “lies Edward the Eighth!” And all

Henry could reply was that, if ever he got out from under those bags, they could cable the news

to him collect. I am beginning to see that he has rather less soul than the common wart-hog.

When we got to Westminster Abbey, we spent a fascinating hour gazing at the slabs

beneath which lie England’s mighty dead and on top of which lie the sandbags placed there in

case of bombs. “There,” I said to Henry in a hushed whisper, “lies Edward the Eighth!” And all

Henry could reply was that, if ever he got out from under those bags, they could cable the news

to him collect. I am beginning to see that he has rather less soul than the common wart-hog.

THURSDAY. Henry is little or no use in a crisis. Tonight, returning from a ramble, we found

ourselves on an island in Piccadilly. It was pitch dark, and the only lights to be seen were

those of taxi-cabs waiting to swoop down on us directly we left our place of safety. And all Henry

could do was to say that now perhaps I was satisfied and this was what came of listening to

me and letting me drag him to London.  We should have spent the night there, if it had not

been for a friendly policeman, who seemed to know his way about and led us through the darkness

to the opposite sidewalk. Henry grumbled all the way. “There isn’t a back alley in America

that’s lighted like this,” he said. “Why don’t you wire up?” The policeman thanked him in a

dignified way, and the episode ended. More and more the conviction is creeping over

me that, Henry is a boob from Boob Center.

We should have spent the night there, if it had not

been for a friendly policeman, who seemed to know his way about and led us through the darkness

to the opposite sidewalk. Henry grumbled all the way. “There isn’t a back alley in America

that’s lighted like this,” he said. “Why don’t you wire up?” The policeman thanked him in a

dignified way, and the episode ended. More and more the conviction is creeping over

me that, Henry is a boob from Boob Center.

FRIDAY. To-day has ended everything. I induced Henry to take me to lunch at the Cheshire Cheese. “This place,” he said, looking around him, “reminds me of Germany.” (He has, I believe, occasionally visited rathskellers in New York.) “Bring me a stein of Wurzburger, or Moerlein, or Anheuser Busch.” It sounded just like an interned German expressing his opinion of Sir Edward Grey, and I saw many suspicious glances cast at him. And then, when we had finished lunch, he went out into the street and took a snapshot of the place. The entire police force of London seemed to descend on him as one man. Waiters streamed out of the restaurant to testify that they had heard Henry making abusive remarks in German about the king. The last I saw of him, as—with an aching heart—I left the scene, they were taking him away to search him for hidden plans.

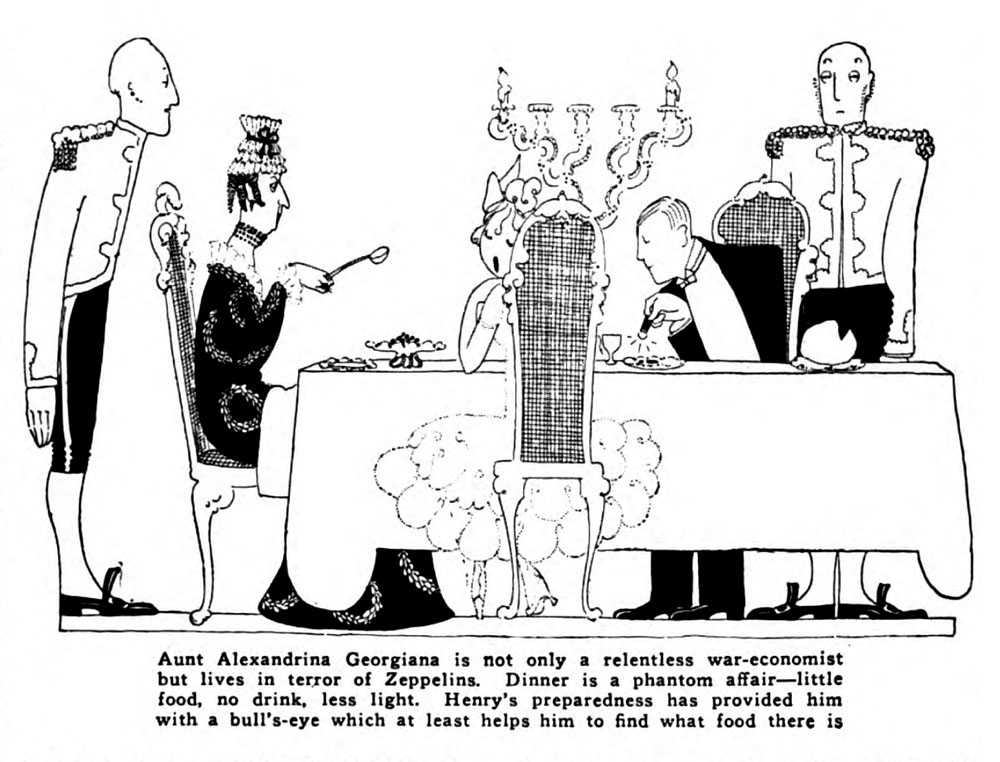

2 a.m. Henry has returned. He identified himself as an American citizen by applying to an aunt

of his who lives somewhere in London, and he says the aunt has insisted on our spending the

remainder of our honeymoon at her house. She has religious mania and is a vegetarian. We dine

with Aunt Georgiana in the suburbs this evening, and remain as her guests for the night.

2 a.m. Henry has returned. He identified himself as an American citizen by applying to an aunt

of his who lives somewhere in London, and he says the aunt has insisted on our spending the

remainder of our honeymoon at her house. She has religious mania and is a vegetarian. We dine

with Aunt Georgiana in the suburbs this evening, and remain as her guests for the night.

6 a.m. I have just wakened Henry from a troubled sleep to inform him that there will not be any remainder of our honeymoon. I am going out to get a divorce.

SATURDAY. Homeward bound. Have instructed my New York lawyer by wireless to get me a divorce and to have it ready for me when I land. I have also sent a wireless to Eustace, telling him to meet the boat and take me out to lunch. My faith in men is well-nigh shattered, but, if Eustace means business,—as he has often hinted—I shall insist that we spend our honeymoon in the neighborhood of Broadway and Forty-second Street.