The Saturday Evening Mail: New York, October 5, 1912.

THE PRINCE

AND BETTY

By Pelhan G. Wodehouse

ILLUSTRATED BY JOHN V. RANCK

CHAPTER VII.—(Continued.)

MR. SCOBELL was pacing the room in an ecstasy of triumphant rhetoric. “There’s another thing,” he said, swinging round suddenly and causing his sister to drop another stitch. “Maybe you think he’s some kind of a Dago, this guy? Maybe that’s what’s biting you. Let me tell you that he’s an American—pretty near as much an American as you are yourself.”

Betty stared at him.

“An American!”

“Don’t believe it, eh? Well, let me tell you that his mother was born and raised in Jersey, and that he has lived all his life in the States. He’s no little runt of a Dago. No, sir. He’s a Harvard man, six-foot high and weighs two hundred pounds. That’s the sort of man he is. I guess that’s not American enough for you, maybe? No?”

“You do shout so, Bennie!” murmured Miss Scobell. “I’m sure there’s no need.”

Betty uttered a cry. Something had told her who he was, this Harvard man who had sold himself. That species of sixth sense which lies undeveloped at the back of our minds during the ordinary happenings of life wakes sometimes in moments of keen emotion. At its highest, it is prophecy; at its lowest, a vague presentiment. It woke in Betty now. There was no particular reason why she should have connected her stepfather’s words with John. The term he had used was an elastic one. Among the visitors to the island there were probably several Harvard men. But somehow she knew.

“Who is he?” she cried. “What was his name before he—when he——?”

“His name?” said Mr. Scobell. “John Maude. Maude was his mother’s name. She was a Miss Westley. Here, where are you going?”

Betty was walking slowly toward the door. Something in her face checked Mr. Scobell.

“I want to think,” she said quietly. “I’m going out.”

IN days of old, in the age of legend, omens warned heroes of impending doom. But to-day the gods have grown weary, and we rush unsuspecting on our fate. No owl hooted, no thunder rolled from the blue sky as John went up the path to meet the white dress that gleamed between the trees. His heart was singing within him. She had come. She had not forgotten, or changed her mind, or willfully abandoned him. His mood lightened swiftly. Humility vanished. He was not such an outcast, after all. He was some one. He was the man Betty Silver had come to meet.

But with the sight of her face came reaction.

Her face was pale and cold and hard. She did not speak or smile. As she drew near she looked at him, and there was that in her look which set a chill wind blowing through the world and cast a veil across the sun.

And in this bleak world they stood silent and motionless while eons rolled by.

Betty was the first to speak.

“I’m late,” she said.

John searched in his brain for words, and came empty away. He shook his head dumbly.

“Shall we sit down?” said Betty.

John indicated silently the sandstone rock on which he had been communing with himself.

They sat down. A sense of being preposterously and indecently big obsessed John. There seemed no end to him. Wherever he looked, there were hands and feet and legs. He was a vast blot on the face of the earth. He glanced out of the corner of his eye at Betty. She was gazing out to sea.

He dived into his brain again. It was absurd! There must be something to say.

And then he realized that a worse thing had befallen. He had no voice. It had gone. He knew that, try he never so hard to speak, he would not be able to utter a word. A nightmare feeling of unreality came upon him. Had he ever spoken? Had he ever done anything but sit dumbly on that rock, looking at those sea gulls out in the water?

He shot another swift glance at Betty, and a thrill went through him. There were tears in her eyes.

The next moment—the action was almost automatic—his left hand was clasping her right, and he was moving along the rock to her side.

She snatched her hand away.

His brain, ransacked for the third time, yielded a single word.

“Betty!”

She got up quickly.

In the confused state of his mind, John found it necessary if he were to speak at all, to say the essential thing in the shortest possible way. Polished periods are not for the man who is feeling deeply.

He blurted out, huskily, “I love you!” and finding that this was all that he could say, was silent.

EVEN to himself the words, as he spoke them, sounded bald and meaningless. To Betty, shaken by her encounter with Mr. Scobell, they sounded artificial, as if he were forcing himself to repeat a lesson. They jarred upon her.

“Don’t!” she said sharply. “Oh, don’t!”

Her voice stabbed him. It could not have stirred him more if she had uttered a cry of physical pain.

“Don’t! I know. I’ve been told.”

“Been told?”

She went on quickly.

“I know all about it. My stepfather has just told me. He said—he said you were his—” she choked—“his hired man; that he paid you to stay here and advertise the Casino. Oh, it’s too horrible! That it should be you! You, who have been—you can’t understand what you—have been to me—ever since we met; you couldn’t understand. I can’t tell you—a sort of help—something—something that—I can’t put it into words. Only it used to help me just to think of you. It was almost impersonal. I didn’t mind if I never saw you again. I didn’t expect ever to see you again. It was just being able to think of you. It helped—you were something I could trust. Something strong—solid.” She laughed bitterly. “I suppose I made a hero of you. Girls are fools. But it helped me to feel that there was one man alive who—who put his honor above money——”

SHE broke off. John stood motionless, staring at the ground. For the first time in his easy-going life he knew shame. Even now he had not grasped to the full the purport of her words. The scales were falling from his eyes, but as yet he saw but dimly.

She began to speak again, in a low, monotonous voice, almost as if she were talking to herself. She was looking past him, at the gulls that swooped and skimmed above the glittering water.

“I’m so tired of money—money—money. Everything’s money. Isn’t there a man in the world who won’t sell himself? I thought that you—I suppose I’m stupid. It’s business, I suppose. One expects too much.”

She looked at him wearily.

“Good-by,” she said. “I’m going.”

He did not move.

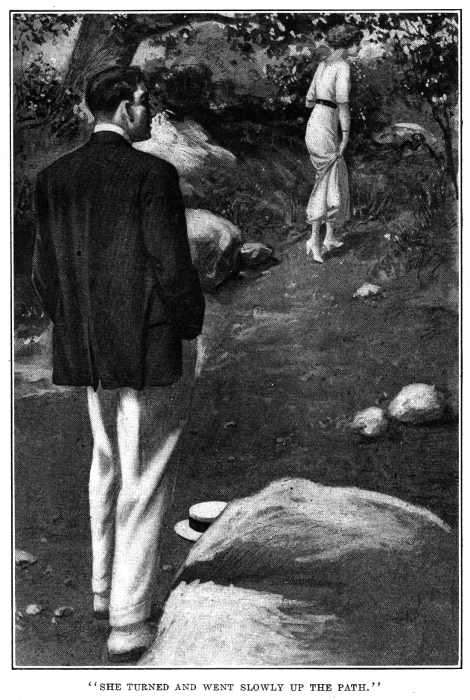

She turned and went slowly up the path. Still he made no movement. A spell seemed to be on him. His eyes never left her as she passed into the shadow of the trees. For a moment her white dress stood out clearly. She had stopped. With his whole soul he prayed that she would look back. And suddenly a strange weakness came upon John. He trembled. The hillside flickered before his eyes for an instant, and he clutched at the sandstone rock to steady himself.

Then his brain cleared, and he found himself thinking swiftly. He could not let her go like this. He must overtake her. He must stop her. He must speak to her. He must say—he did not know what it was that he would say—anything, so that he spoke to her again.

He raced up the path, calling her name. No answer came to his cries. Above him lay the hillside, dozing in the noonday sun; below, the Mediterranean, sleek and blue, without a ripple. He stood alone in a land of silence and sleep.

CHAPTER VIII.

AN ULTIMATUM FROM THE THRONE.

AT half-past twelve that morning business took Mr. Benjamin Scobell to the royal palace. He was not a man who believed in letting the grass grow under his feet. He liked to think of himself as swift and sudden—the Human Thunderbolt.

In this matter of the royal alliance, it was his intention to have at it and clear it up at once. Having put his views clearly before Betty, he now proposed to lay them with equal clarity before the prince. There was no sense in putting the thing off.

That Betty had not received his information with joy did not distress him. He had a poor opinion of the feminine intelligence. Girls got their minds full of nonsense from reading novels and seeing plays—like Betty. Betty objected to those who were wiser than herself providing a perfectly good prince for her to marry. Some fool notion of romance, of course. Not that he was angry. He did not blame her any more than the surgeon blames a patient for the possession of an unsuitable appendix. There was no animus in the matter. Her mind was suffering from foolish ideas, and he was the surgeon whose task it was to operate upon it. That was all. One had to expect foolishness in women. It was their nature. The only thing to do was to tie a rope to them and let them run around till they were tired of it, then pull them in. He saw his way to managing Betty.

NOR did he anticipate trouble with John. He had taken an estimate of John’s character, and it did not seem to him likely that it contained unsuspected depths. He set John down, as he had told Betty, as a young man acute enough to know when he had a good job and sufficiently sensible to make concessions in order to retain it. Betty, after the manner of woman, might make a fuss before yielding to the inevitable, but from level-headed John he looked for placid acquiescence.

His mood, as the automobile whirred its way down the hill toward the town, was sunny. He looked on life benevolently and found it good. The view appealed to him more than it had managed to do on other days. As a rule, he was the man of blood and iron who had no time for admiring scenery, but to-day he vouchsafed it a not unkindly glance. It was certainly a dandy little place, this island of his. A vineyard on the right caught his eye. He made a mental note to uproot it and run up a hotel in its place. Farther down the hill he selected a site for a villa, where the mimosa blazed, and another where at present there were a number of utterly useless violets. A certain practical element was apt, perhaps, to color Mr. Scobell’s half-hours with nature.

The sight of the steamboat leaving the harbor on its journey to Marseilles gave him another idea. Now that Mervo was a going concern, a real live proposition, it was high time that it should have an adequate service of boats. The present system of one a day was absurd. He made a note to look into the matter. These people wanted waking up.

ARRIVING at the palace, he was informed that his highness had gone out shortly after breakfast, and had not returned. The majordomo gave the information with a twinkle of disapproval in his voice. Before taking up his duties at Mervo, he had held a similar position in the household of a German prince, where rigid ceremonial obtained, and John’s cheerful disregard of the formalities frankly shocked him. To take the present case for instance: When his highness of Swartzheim had felt inclined to enjoy the air of a morning, it had been a domestic event full of stir and pomp. He had not merely crammed a soft hat over his eyes and strolled out with his hands in his pockets, but without a word to his household staff as to where he was going or when he might be expected to return.

Mr. Scobell received the news equably, and directed his chauffeur to return to the villa. He could not have done better, for, on his arrival, he was met with the information that his highness had called to see him shortly after he had left, and was now waiting in the morning room.

The sound of footsteps came to Mr. Scobell’s ears as he approached the room. His highness appeared to be pacing the floor like a caged animal at the luncheon hour.

The resemblance was heightened by the expression in the royal eye as his highness swung round at the opening of the door and faced the financier.

“Why, say, prince,” said Mr. Scobell, “this is lucky. I been looking for you. I just been to the palace, and the main guy there told me you had gone out.”

“I did. And I met your stepdaughter.”

MR. SCOBELL was astonished. Fate was certainly smoothing his way if it arranged meetings between Betty and the prince before he had time to do it himself. There might be no need for the iron hand after all.

“You did?” he said. “Say, how the Heck did you come to do that? What did you know about Betty?”

“Miss Silver and I had met before, in America, when I was in college.”

Mr. Scobell slapped his thigh joyously.

“Gee, it’s working out like a fiction story in the magazines!”

“Is it?” said John. “How? And, for the matter of that, what?”

Mr. Scobell answered question with question.

“Say, prince, you and Betty were pretty good friends in the old days, I guess?”

John looked at him coldly.

“We won’t discuss that, if you don’t mind,” he said.

His tone annoyed Mr. Scobell. Off came the velvet glove, and the iron hand displayed itself. His green eyes glowed dully and the tip of his nose wriggled, as was its habit in times of emotion.

“Is that so?” he cried, regarding John with disfavor. “Well, I guess! Won’t discuss it! You gotta discuss it, your royal Texas League highness! You want making a head shorter, my bucko. You——”

John’s demeanor had become so dangerous that he broke off abruptly, and with an unostentatious movement, as of a man strolling carelessly about his private sanctum, put himself within easy reach of the door handle.

He then became satirical.

“Maybe your serene, imperial two-by-fourness would care to suggest a subject we can discuss?”

John took a step forward.

“Yes, I will,” he said between his teeth. “You were talking to Miss Silver about me this morning. She told me one or two of the things you said, and they opened my eyes. Until I heard them I had not quite understood my position. I do now. You said, among other things, that I was your hired man.”

“It wasn’t intended for you to hear,” said Mr. Scobell, slightly mollified, “and Betty shouldn’t oughter have handed it to you. I don’t wonder you feel raw. I wouldn’t say that sort of thing to a guy’s face. Sure, no. Tact’s my middle name. But, since you have heard it, well——!”

“Don’t apologize. You were quite right. I was a fool not to see it before. No description could have been fairer. You might have said much more. You might have added that I was nothing more than a steerer for a gambling hell.”

“Oh, come, prince!”

THERE was a knock at the door. A footman entered, bearing, with a detached air, as if he disclaimed all responsibility, a letter on a silver tray.

Mr. Scobell slit the envelope, and began to read. As he did so his eyes grew round, and his mouth slowly opened till his cigar stump, after hanging for a moment from his lower lip, dropped off like an exhausted bivalve and rolled along the carpet.

“Prince,” he gasped, “she’s gone. Betty!”

“Gone! What do you mean?”

“She’s beaten it. She’s half way to Marseilles by now. Gee, and I saw the darned boat going out!”

“She’s gone!”

“This is from her. Listen what she says:

“By the time you read this I shall be gone. I am going back to America as quickly as I can. I am giving this to a boy to take to you directly the boat has started. Please do not try to bring me back. I would sooner die than marry the prince.”

John started violently.

“What!” he cried.

Mr. Scobell nodded sympathy.

“That’s what she says. She sure has it in bad for you. What does she mean? Seeing you and she are old friends——”

“I don’t understand. Why does she say that to you? Why should she think that you knew that I had asked her to marry me?”

“Eh?” cried Mr. Scobell. “You asked her to marry you? And she turned you down! Prince, this beats the band. Say, you and I must get together and do something. The girl’s mad. See here, you aren’t wise to what’s been happening. I been fixing this thing up. I fetched you over here, and then I fetched Betty, and I was going to have you two marry. I told Betty all about it this morning.”

JOHN cut through his explanation with a sudden sharp cry. A blinding blaze of understanding had flashed upon him. It was as if he had been groping his way in a dark cavern and had stumbled unexpectedly into brilliant sunlight. He understood everything now. Every word that Betty had spoken, every gesture that she had made, had become amazingly clear. He saw now why she had shrunk back from him, why her eyes had worn that look. He dared not face the picture of himself as he must have appeared in those eyes, the man whom Mr. Benjamin Scobell’s Casino was paying to marry her, the hired man earning his wages by speaking words of love.

A feeling of physical sickness came over him. He held to the table for support as he had held to the sandstone rock. And then came rage, rage such as he had never felt before, rage that he had not thought himself capable of feeling. It swept over him in a wave, pouring through his veins and blinding him, and he clung to the table till his knuckles whitened under the strain, for he knew that he was very near to murder.

A minute passed. He walked to the window, and stood there, looking out. Vaguely he heard Mr. Scobell’s voice at his back, talking on, but the words had no meaning for him.

Madame Eulalie’s Rare Plums

Madame Eulalie’s Rare Plums