Liberty, September 1, 1928

Part Twelve

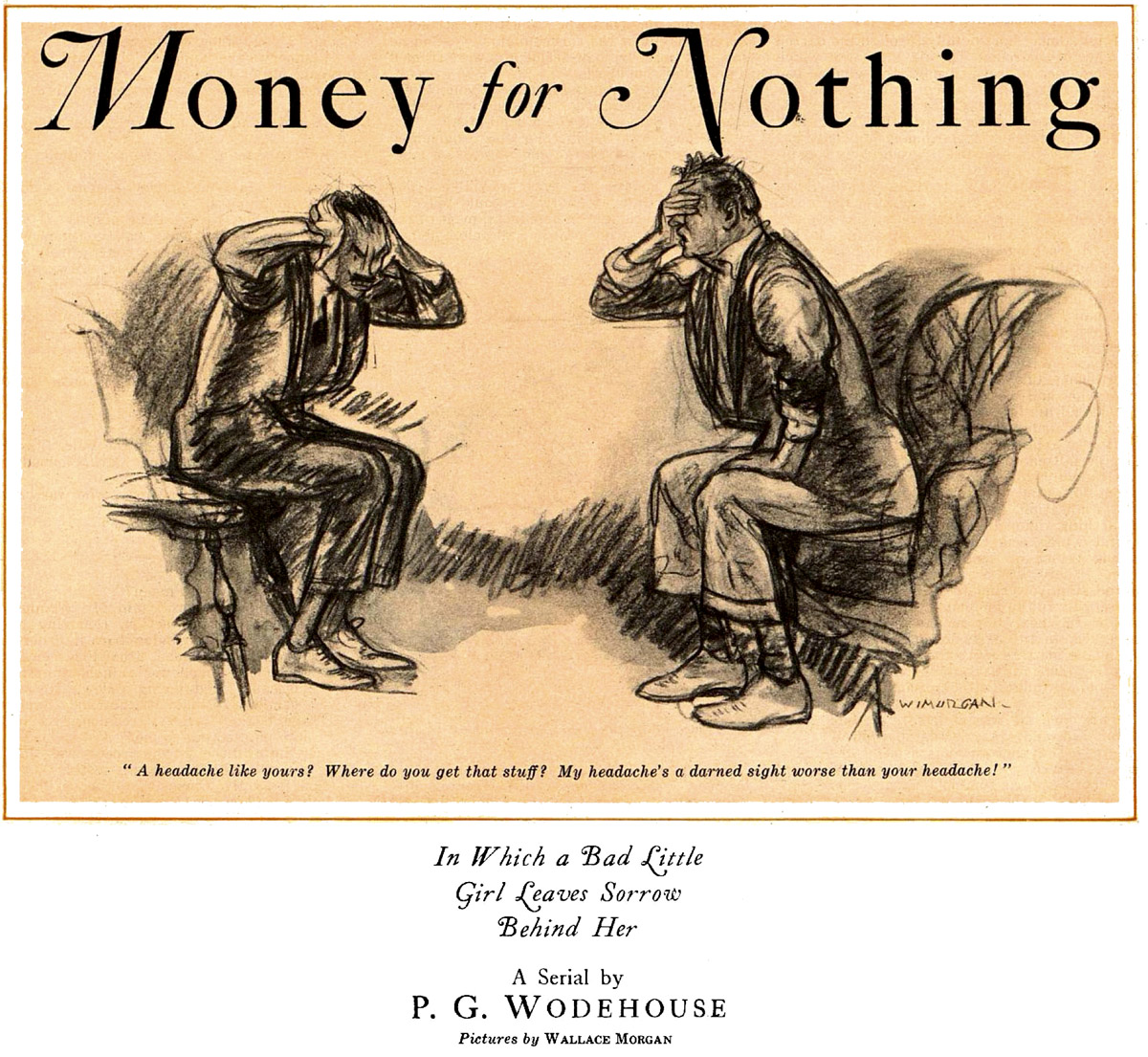

IT had been the opinion of Dolly Molloy, expressed during her conversation with Mr. Twist, that John, on awaking from his drugged slumber, would find himself suffering from a headache. The event proved her a true prophet.

John, as became one who prized physical fitness, had been all his life a rather unusually abstemious young man. But on certain rare occasions dotted through the years of his sojourn at Oxford he had permitted himself to relax—as, for instance, the night of his twenty-first birthday; boat-race night in his freshman year; and, perhaps most notable of all, the night of the university football match in the season when he had first found a place on the Oxford team and had helped to win one of the most spectacular games ever seen at Twickenham.

To celebrate each of these events he had lapsed from his normal austerity, and every time had awakened on the morrow to a world full of grayness and horror and sharp, shooting pains. But never had he experienced anything to compare with what he was feeling now.

He was dimly conscious that strange things must have been happening to him, and that these things had ended by depositing him on a strange bed in a strange room. But he was at present in no condition to give his situation any sustained thought. He merely lay perfectly still, concentrating all his powers on the difficult task of keeping his head from splitting in half.

When eventually, moving with exquisite care, he slid from the bed and stood up, the first thing of which he became aware was that the sun had sunk so considerably that it was now shining almost horizontally through the barred window of the room. The air, moreover, which accompanied its rays through the window had that cool fragrance which indicates the approach of evening.

Poets have said some good things, in their time, about this particular hour of the day; but to John on this occasion it brought no romantic thoughts. He was merely bewildered. He had started out from Rudge not long after 11 in the morning, and here it was late afternoon.

He moved to the window, feeling like Rip van Winkle. And presently the sweet air, playing about his aching brow, restored him so considerably that he was able to make deductions and arrive at the truth.

The last thing he could recollect was the man Twist handing him a tall glass. In that glass, it now became evident, must have lurked the cause of all his troubles. With an imbecile lack of the most elementary caution, inexcusable in one who had been reading detective stories all his life, he had allowed himself to be drugged.

It was a bitter thought, but he was not permitted to dwell on it for long.

Gradually, driving everything else from his mind, there stole upon him the realization that unless he found something immediately to slake the thirst which was burning him up he would perish of spontaneous combustion. There was a jug on the wash-stand, and, tottering to it, he found it mercifully full to the brim.

For the next few moments he was occupied, to the exclusion of all other mundane matters, with the task of seeing how much of the contents of this jug he could swallow without pausing for breath.

For the next few moments he was occupied, to the exclusion of all other mundane matters, with the task of seeing how much of the contents of this jug he could swallow without pausing for breath.

This done, he was at leisure to look about him and examine the position of affairs. That he was a prisoner was proved directly he tested the handle of the door. And, as further evidence, there were those bars on the window.

Whatever else might be doubtful, the one thing certain was that he would have to remain in this room until somebody came along and let him out.

His first reaction on making this discovery was a feeling of irritation at the silliness of the whole business. Where was the sense of it? Did this man Twist suppose that in the heart of peaceful Worcestershire he could immure a fellow forever in an upper room of his house?

And then his clouded intellect began to function more nimbly.

Twist’s behavior, he saw, was not so childish as he had supposed. It had been imperative for him to gain time in order to get away with his loot; and, John realized, he had most certainly gained it. And the longer he remained in this room the more complete would be the scoundrel’s triumph.

John became active. He went to the door again and examined it carefully. A moment’s inspection showed him that nothing was to be hoped for from that quarter. A violent application of his shoulder did not make this solid oak so much as quiver.

He tried the window. The bars were firm. Tugging had no effect on them.

There seemed to John only one course to pursue.

He shouted.

It was an injudicious move. The top of his head did not actually come off, but it was a very near thing.

By a sudden clutch at both temples he managed to avert disaster in the nick of time, and tottered weakly to the bed. There for some minutes he remained while unseen hands drove red-hot rivets into his skull.

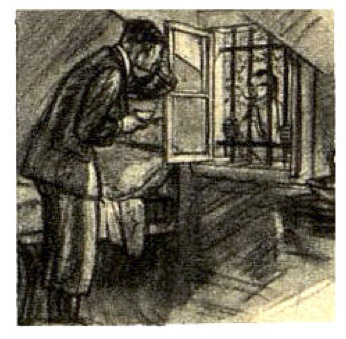

Presently the agony abated. He was able to rise again and make his way feebly to the jug, which he had now come to look on as his only friend in the world. He had just finished his second nonstop draft when something attracted his notice out of the corner of his eye, and he saw that in the window beside him were framed a head and shoulders.

“Hoy!” observed the head, in a voice like a lorry full of steel girders passing over cobblestones. “I’ve brought you a cuppertea.”

“Hoy!” observed the head, in a voice like a lorry full of steel girders passing over cobblestones. “I’ve brought you a cuppertea.”

The head was red in color and ornamented halfway down by a large and impressive mustache, waxed at the ends. The shoulders were broad and square, the eyes prawnlike. The whole apparition, in short, one could tell at a glance, was a sample or first installment of the person of a sergeant major. And unless he had dropped from heaven—which, from John’s knowledge of sergeant majors, seemed unlikely—the newcomer must be standing on the top of a ladder.

And such, indeed, was the case. Sergeant Major Flannery, though no acrobat, had nobly risked life and limb by climbing to this upper window to see how his charge was getting on and to bring him a little refreshment.

“Take your cuppertea, young fellow,” said Mr. Flannery.

THE hospitality had arrived too late. In the matter of tea drinking John was handicapped by the fact that he had just swallowed approximately a third of a jug of water. He regretted to be compelled to reject the contribution for lack of space. But, as what he desired most at the moment was human society and conversation, he advanced eagerly to the window.

“Who are you?” he asked.

“Flannery’s my name, young fellow.”

“How did I get here?”

“In that room?”

“Yes.”

“I put you there.”

“You did, did you?” said John. “Open this door at once, damn you!”

The sergeant major shook his head.

“Language!” he said reprovingly. “Profanity won’t do you no good, young man. Cursing and swearing won’t ’elp you. You just drink your cuppertea and don’t let’s have no nonsense. If you’d made a ’abit in the past of drinking more tea and less of the other thing, you wouldn’t be in what I may call your present predicament.”

“Will you open this door?”

“No, sir, I will not open that door. There aren’t going to be no doors opened till your conduct and behavior has been carefully examined in the course of a day or so and we can be sure there’ll be no verlence.”

“Listen,” said John, curbing a desire to jab at this man through the bars with the teaspoon, “I don’t know who you are—”

“Flannery’s the name, sir, as I said before. Sergeant Major Flannery.”

“—but I can’t believe you’re in this business—”

“Indeed I am, sir. I am Dr. Twist’s assistant.”

“But this man Twist is a criminal, you fool!”

Sergeant Major Flannery seemed pained rather than annoyed.

“Come, come, sir. A little civility, if you please. This what I may call contumacious attitude isn’t helping you. Surely you can see that for yourself. Always remember, sir, the voice with the smile wins.”

“This fellow Twist burgled our house last night. And all the while you’re keeping me shut up here he’s getting away.”

“Is that so, sir? What house would that be?”

“Rudge Hall.”

“Never heard of it.”

“It’s near Rudge-in-the-Vale. Twenty miles from here. Mr. Carmody’s place.”

“Mr. Lester Carmody, who was here taking the cure?”

“Yes. I’m his nephew.”

“His nephew, eh?”

“Yes.”

“Come, come!”

“What do you mean?”

“It so ’appens,” said Mr. Flannery with quiet satisfaction, removing one hand from the window bars in order to fondle his mustache, “that I’ve seen Mr. Carmody’s nephew. Tallish, thinnish, pleasant faced young fellow. He was over here to visit Mr. Carmody during the latter’s temp’ry residence. I had him pointed out to me.”

Painful though the process was, John felt compelled to grit his teeth.

“That was Mr. Carmody’s other nephew.”

“Other nephew, eh?”

“My cousin.”

“Your cousin, eh?”

“His name’s Hugo.”

“Hugo, eh?”

“Good God!” cried John. “Are you a parrot?”

Mr. Flannery, if he had not been standing on a ladder, would no doubt have drawn himself up haughtily at this outburst. Being none too certain of his footing, he contented himself with looking offended.

“No, sir,” he said, with a dignity which became him well; “in reply to your question, I am not a parrot. I am a salaried assistant at Dr. Twist’s health establishment, detailed to look after the patients and keep them away from the cigarettes and see that they do their exercise in a proper manner. And, as I said to the young lady, I understand human nature and am a match for artfulness of any description. What’s more, it was precisely this kind of artfulness on your part the young lady warned me against.

“ ‘Be careful, sergeant major,’ she said to me, clasping her ’ands in what I may call an agony of appeal, ‘that this poor, misguided young son of a what-not don’t come it over you with his talk about being the lost heir of some family living in the near neighborhood. Because he’s sure to try it on, you can take it from me, sergeant major,’ she said.

“And I said to the young lady, ‘Miss,’ I said, ‘he won’t come it over Egbert Flannery. Not him. I’ve seen too much of that sort of thing, miss,’ I said.

“And the young lady said, ‘Gawd’s strewth, sergeant major,’ she said, ‘I wish there was more men in the world like you, sergeant major, because then it would be a damn sight better place than it is, sergeant major.’ ”

He paused. Then, realizing an omission, added “she said.”

John clutched at his throbbing head.

“Young lady? What young lady?”

“You know well enough what young lady, sir. The young lady what brought you here to leave you in our charge. That young lady.”

“That young lady?”

“Yes, sir. The one who brought you here.”

“Brought me here?”

“And left you in our charge.”

“Left me in your charge?”

“Come, come, sir!” said Mr. Flannery. “Are you a parrot?”

The adroit thrust made no impression on John. His mind was too busy to recognize it for what it was—viz., about the cleverest repartee ever uttered by a noncommissioned officer of his majesty’s regular forces.

A MONSTROUS suspicion had smitten him, with the effect almost of a physical blow. Suspicion? It was more than a suspicion. If it was at Dolly Molloy’s request that he was now locked up in this infernal room, then, bizarre as it might seem, Dolly Molloy must in some way be connected with the nefarious activities of the man Twist.

The links that connected the two might be obscure, but as to the fact there could be no doubt whatever.

“You mean—” he gasped.

“I mean your sister, sir, who brought you over here in her car.”

“What! That was my car.”

“No, no, sir, that won’t do. I saw her myself driving off in it some hours ago. She waved her ’and to me,” said Mr. Flannery, caressing his mustache and allowing a note of tender sentiment to creep into his voice. “Yes, sir! She turned and waved her ’and.”

John made no reply. He was beyond speech. Trifling though it might seem to an insurance company, in comparison with the loss of Rudge Hall’s more valuable treasures, the theft of the two-seater smote him a blow from which he could not hope to rally. He loved his Widgeon Seven.

He had nursed it, tended it, oiled it, watered it, watched over it in sickness and in health as if it had been a baby sister. And now it had gone.

“Look here!” he cried feverishly. “You must let me out of here. At once!”

“No, sir. I promised your sister—”

“She isn’t my sister! I haven’t got a sister! Good heavens, man, can’t you understand—”

“I understand very well, sir. Artfulness! I was prepared for it.” Sergeant Major Flannery paused for an instant. “The young lady,” he said dreamily, “was afraid, too, that you might try to bribe me. She warned me most particular.”

John did not speak. His Widgeon Seven! Gone!

“Bribe me!” repeated Sergeant Major Flannery, his eyes widening. It was evident that the mere thought of such a thing sickened this good man. “She said you would try to bribe me to let you go.”

“Well, you can make your mind easy,” said John between his teeth. “I haven’t any money.”

There was a moment’s silence. Then Mr. Flannery said “Ho!” in a rather short manner. And silence fell again.

It was broken by the sergeant major in a moralizing vein.

“It’s a wonder to me,” he said, and there was peevishness in his voice, “that a young fellow with a lovely sister like what you’ve got can bring himself to lower himself to the beasts of the field, as the saying is. Drink in moderation is one thing. Mopping it up and becoming verlent and a nuisance to all is another.

“If you’d ever seen one of them lantern slides showing what alcohol does to the liver of the excessive drinker, maybe you’d have pulled up sharp while there was time. And not,” said the sergeant major, still with that oddly querulous note in his voice, “have wasted all your money on what could only do you ’arm. If you ’adn’t of give in so to your self-indulgence and what I may call besottedness, you would now ’ave your pocket full of money to spend how you fancied.” He sighed. “Your cuppertea’s got cold,” he said moodily.

“I don’t want any tea.”

“Then I’ll be leaving you,” said Mr. Flannery. “If you require anything, press the bell. Nobody’ll take any notice of it.”

He withdrew cautiously down the ladder; and, having paused at the bottom to shake his head reproachfully, disappeared from view.

JOHN did not miss him. His desire for company had passed. What he wanted now was to be alone and to think. Not that there was any likelihood of his thoughts being pleasant ones. The more he contemplated the iniquity of the Molloy family, the deeper did the iron enter into his soul. If ever he set eyes on Thomas G. Molloy again—

He set eyes on him again, oddly enough, at this very moment. From where he stood looking through the bars of the window, there was visible to him a considerable section of the drive. And up the drive at this juncture, toiling painfully, came Mr. Molloy in person, seated on a bicycle.

As John craned his neck and glared down with burning eyes, the rider dismounted; and the bicycle, which appeared to have been waiting for the chance, bit him neatly in the ankle with its left pedal. John was too far away to hear the faint cry of agony which escaped the suffering man, but he could see his face. It was a bright crimson face, powdered with dust, and its features were twisted in anguish.

John went back to the jug and took another long drink. In the spectacle just presented to him he had found a faint, feeble glimmering of consolation.

II

ON leaving John, Sergeant Major Flannery’s first act was to go to what he was accustomed to call the orderly room and make his report. He reached it only a few minutes after its occupant’s return to consciousness. Chimp Twist had opened his eyes and staggered to his feet at just about the moment when the sergeant major was offering John the cup of tea.

Mr. Twist’s initial discovery, like John’s, was that he had a headache. He then set himself to try to decide where he was. His mind clearing a little, he was enabled to gather that he was in England, and—assembling the facts by degrees—in his study at Healthward Ho (formerly Graveney Court), Worcestershire. After that, everything came back to him, and he stood holding to the table with one hand and still grasping the lily with the other, and gave himself up to scorching reflections on the subject of the resourceful Mrs. Molloy.

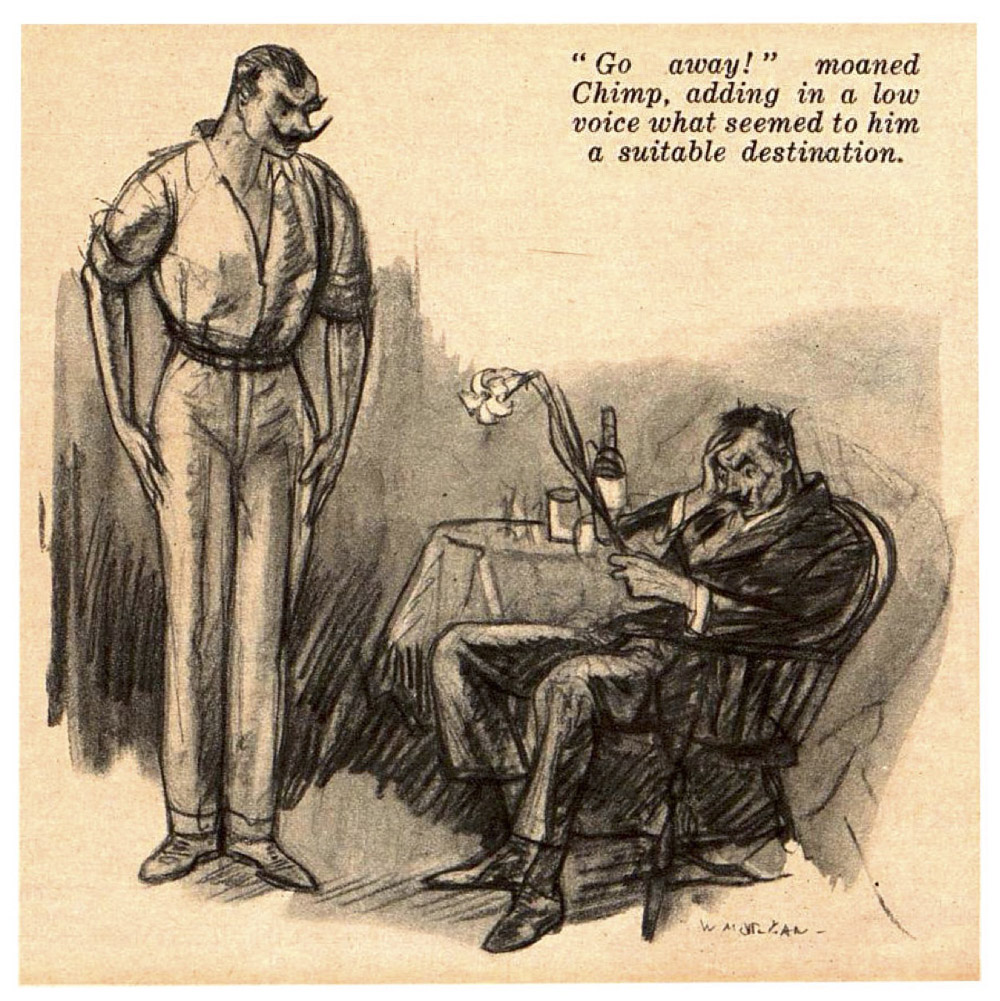

He was still busy with these when there came a forceful knock on the door and Sergeant Major Flannery entered.

Chimp’s grip on the table tightened. He held himself together like one who sees a match set to a train of gunpowder and awaits the shattering explosion. His visitor’s lips had begun to move, and Chimp could guess how that parade ground voice was going to sound to a man with a headache like his.

“H’rarph’m,” began Mr. Flannery, clearing his throat. And Chimp, with a sharp cry, reeled to a chair and sank into it. The noise had hit him like a shell. He cowered where he sat, peering at the sergeant major with haggard eyes.

“Ooer!” boomed Mr. Flannery, noting these symptoms. “You aren’t looking up to the mark, Mr. Twist.”

Chimp dropped the lily, feeling the necessity of having both hands free. He found he experienced a little relief if he put the palms over his eyes and pressed hard.

“I’ll tell you what it is, sir,” roared the sympathetic sergeant major. “What’s ’appened ’ere is that the nasty, feverish cold of yours has gone and struck inwards. It’s left your ’ead and has penetrated internally to your vitals. If only you’d have took taraxacum and hops, like I told you—”

“Go away!” moaned Chimp, adding in a low voice what seemed to him a suitable destination.

Mr. Flannery regarded him with mild reproach.

“There’s nothing gained, Mr. Twist, by telling me to get to ’ell out of here. I’ve merely come for the single and simple reason that I thought you would wish to know I’ve had a conversation with the verlent case upstairs, and the way it looks to me, sir, subject to your approval, is that it ’ud be best not to let him out from under lock and key for some time to come. True, ’e did not attempt anything in the nature of actual physical attack, being prevented, no doubt, by the fact that there was iron bars between him and me, but his manner throughout was peculiar, not to say odd, and I recommend that all communications be conducted till further notice through the window.”

“Do what you like,” said Chimp faintly.

“It isn’t what I like, sir,” bellowed Mr. Flannery virtuously. “It’s what you like and instruct, me being in your employment and only ’ere to carry out your orders smartly as you give them. And there’s one other matter, sir. As perhaps you are aware, the young lady went off in the little car—”

“Don’t talk to me about the young lady!”

“I was only about to say, Mr. Twist, that you will doubtless be surprised to hear that, for some reason or another, having started to go off in the little car, the young lady apparently decided on second thoughts to continue her journey by train. She left the little car at Lowick station, with instructions that it be returned ’ere.

“I found that young Jakes, the station master’s son, outside with it a moment ago. Tooting the ’orn, he was, the young rascal, and saying he wanted half a crown. Using my own discretion, I gave him sixpence. You may reimburse me at your leisure and when convenient. Shall I take the little car and put it in the garridge, sir?”

Chimp gave eager assent to this proposition, as he would have done to any proposition which appeared to carry with it the prospect of removing this man from his presence.

“IT’s funny, the young lady leaving the little car at the station, sir,” mused Mr. Flannery in a voice that shook the chandelier. “I suppose she happened to reach there at a moment when a train was signaled, and decided that she preferred not to overtax her limited strength by driving to London. I fancy she must have had London as her objective.”

Chimp fancied so, too. A picture rose before his eyes of Dolly and Soapy reveling together in the metropolis, with the loot of Rudge Hall bestowed in some safe place where he would never, never be able to get at it. The picture was so vivid that he uttered a groan.

“Where does it catch you, sir?” asked Mr. Flannery solicitously.

“Eh?”

“The pain, sir. The agony. You appear to be suffering. If you take my advice, you’ll get off to bed and put an ’ot water bottle on your stummick. Lay it right across the abdomen, sir. It may dror the poison out. I had an old aunt—”

“I don’t want to hear about your aunt.”

“Very good, sir. Just as you wish.”

“Tell me about her some other time.”

“Any time that suits you, sir,” said Mr. Flannery agreeably. “Well, I’ll be off and putting the little car in the garridge.”

He left the room; and Chimp, withdrawing his hands from his eyes, gave himself up to racking thought.

A MAN recovering from knockout drops must necessarily see things in a jaundiced light; but it is scarcely probable that, even had he been in robust health, Mr. Twist’s meditations would have been much pleasanter. Condensed, they resolved themselves, like John’s, into a passionate wish that he could meet Soapy Molloy again, if only for a moment.

And he had barely decided that such a meeting was the only thing which life now had to offer, when the door opened again and the maid appeared.

“Mr. Molloy to see you, sir.”

Chimp started from his chair.

“Show him in,” he said in a tense, husky voice.

There was a shuffling noise without, and Soapy appeared in the doorway.

The progress of Mr. Molloy across the threshold of Chimp Twist’s study bore a striking resemblance to that of some spent runner breasting the tape at the conclusion of a more than usually grueling Marathon race.

His hair was disordered, his face streaked with dust and heat, and his legs acted so independently of his body that they gave him an odd appearance of moving in several directions at once. An unbiased observer, seeing him, could not but have felt a pang of pity for this wreck of what had once, apparently, been a fine, upstanding man.

Chimp was not an unbiased observer. He did not pity his old business partner. Judging from a first glance, Soapy Molloy seemed to him to have been caught in some sort of machinery and subsequently run over by several motor lorries, and Chimp was glad of it. He would have liked to seek out the man in charge of that machinery and the drivers of those lorries and reward them handsomely.

“So here you are!” he said.

Mr. Molloy, navigating cautiously, backed and filled in the direction of the armchair. Reaching it after considerable difficulty, he gripped its sides and lowered himself with infinite weariness.

A sharp exclamation escaped him as he touched the cushions. Then, sinking back, he closed his eyes and immediately went to sleep.

Chimp gazed down at him, seething with a resentment that made his headache worse than ever. That Soapy should have had the cold, callous crust to come to Healthward Ho at all after what had happened was sufficiently infuriating. That, having come, he should proceed, without a word of explanation or apology, to treat the study as a bedroom was more than Chimp could endure.

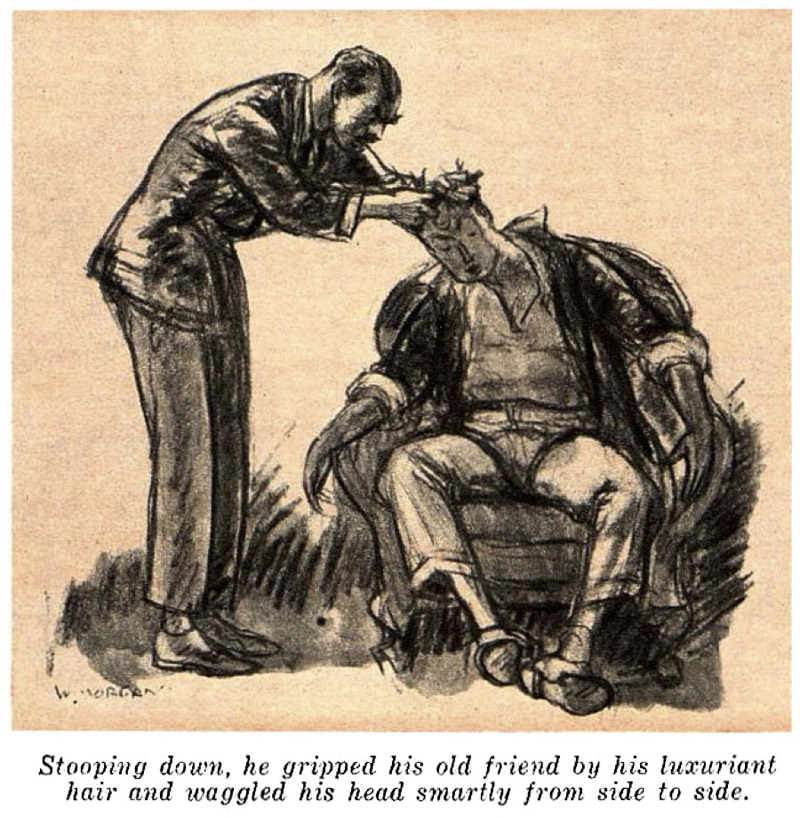

Stooping down, he gripped his old friend by his luxuriant hair and waggled his head smartly from side to side several times. Soapy sat up.

“Eh?” he said, blinking.

“What do you mean, eh?”

“Which—why—where am I?”

“I’ll tell you where you are.”

“Oh!” said Mr. Molloy, intelligence returning.

He sank back among the cushions again, finding their softness delightful. In the matter of seats, a man who has ridden twenty miles on an elderly push bicycle becomes an exacting critic.

“Gee! I feel bad!” he murmured.

It was a natural remark, perhaps, for a man in his condition to make; but it had the effect of adding several degrees Fahrenheit to his companion’s already impressive warmth. For some moments Chimp Twist, wrestling with his emotion, could find no form of self-expression beyond a curious spluttering noise.

“Yes, sir,” proceeded Mr. Molloy, “I feel bad. All the way over here on a bicycle, Chimpie—that’s where I’ve been. It’s in the calf of the leg that it gets me principally. There and around the instep. And I wish I had a dollar for every bruise those darned pedals have made on me.”

“And what about me?” demanded Chimp, at last ceasing to splutter.

“YES, sir,” said Mr. Molloy wistfully; “I certainly wish someone could come along and offer me as much as fifty cents for every bruise I’ve gotten from the ankles upwards. They’ve come out on me like a rash or something.”

“If you had my headache—”

“Yes, I’ve a headache, too,” said Mr. Molloy. “It was the hot sun beating down on my neck that did it. There were times when I thought really I’d have to pass the thing up. Say, if you knew what I feel like—”

“And how about what I feel like?” shrilled Mr. Twist, quivering with self-pity. “A nice thing that was that wife of yours did to me! A fine trick to play on a business partner! Slipping stuff into my highball that laid me out cold. Is that any way to behave? Is that a system?”

Mr. Molloy considered the point.

“The madam is a mite impulsive,” he admitted.

“And leaving me laying there—and putting a lily in my hand!”

“That was her playfulness,” explained Mr. Molloy. “Girls will have their bit of fun.”

“Fun! Say—”

Mr. Molloy felt that it was time to point the moral.

“It was your fault, Chimpie. You brought it on yourself by acting greedy and trying to get the earth. If you hadn’t of stood us up for that sixty-five thirty-five of yours, all this would never have happened. Naturally, no high-spirited girl like the madam wasn’t going to stand for nothing like that.

“But listen while I tell you what I’ve come about. If you’re willing to can all that stuff and have a fresh deal, and a square one this time—one-third to me, one-third to you, and one-third to the madam—I’ll put you hep to something that’ll make you feel good. Yes, sir, you’ll go singing about the house.”

“The only thing you could tell me that would make me feel good,” replied Chimp churlishly, “would be that you’d tumbled off of that bicycle of yours and broken your damned neck.”

Mr. Molloy was pained.

“Is that nice, Chimpie?”

MR. TWIST wished to know if, in the circumstances and after what had occurred, Mr. Molloy expected him to kiss him.

“If you had a headache like mine, Chimpie,” said Mr. Molloy reproachfully, “you’d know how it felt to sit and listen to an old friend giving you the razz.”

Chimp was obliged to struggle for a while with a sudden return of his spluttering.

“A headache like yours? Where do you get that stuff? My headache’s a darned sight worse than your headache!”

“It couldn’t be, Chimpie.”

“If you want to know what a headache really is, you take some of those kayo drops you’re so fond of.”

“Well, putting that on one side,” said Mr. Molloy, wisely forbearing to argue, “let me tell you what I’ve come here about. Chimpie, that guy Carmody has double crossed us. He was on to us from the start.”

“What?”

“Yes, sir. I had it from his own lips in person. And do you know what he done? He took that stuff out of the closet and sent his chauffeur over to Worcester to put it in the left luggage place at the depot there.”

“Gee!” said Mr. Twist, impressed. “That was smooth. Then you haven’t got it, do you mean?”

“No; I haven’t got it.”

Mr. Twist had never expected to feel anything in the nature of elation that day or for many days to come. But at these words something like ecstasy came upon him. He uttered a delighted laugh, which, owing to sudden agony in the head, changed to a muffled howl.

“So, after all your smartness,” he said, removing his hands from his temples as the spasm passed, “you’re no better off than what I am?”

“We’re both sitting pretty, Chimpie, if we get together and act quick.”

“How’s that? Act how?”

“I’ll tell you. This chauffeur guy left the stuff and brought home the ticket and he gave it to that young Carroll fellow!” said Mr. Molloy.

Naturally, the two crooks try to get the ticket from John. But such a move is more easily planned than accomplished. Don’t miss the climax in next week’s installment.

Madame Eulalie’s Rare Plums

Madame Eulalie’s Rare Plums