The Pall Mall Magazine, October 1913

HESE

things happened in New York, which is the capital of the Land

of Unexpectedness; which, like Shakespeare’s divinity, shapes our ends,

rough-hew them how we will. The fool of the family, sent there in

despair to add one more to his list of failures, returns home at the end

of three years a confirmed victim to elephantiasis of the income. His

brother with the bulging forehead and the college education falls,

protesting, into the eighteen dollars a week class. Anything may happen

in New York.

HESE

things happened in New York, which is the capital of the Land

of Unexpectedness; which, like Shakespeare’s divinity, shapes our ends,

rough-hew them how we will. The fool of the family, sent there in

despair to add one more to his list of failures, returns home at the end

of three years a confirmed victim to elephantiasis of the income. His

brother with the bulging forehead and the college education falls,

protesting, into the eighteen dollars a week class. Anything may happen

in New York.

Michael Burke and his brother Tim had journeyed from Skibbereen to the land where the dollar bills grow on trees, without any definite idea what they were going to do when they arrived there; and New York had handled such promising material in its best manner. Michael it had given to the ranks of the police. Tim it had spirited away. Utterly and absolutely he had vanished. Michael had left Ellis Island while Tim was still there. “And divil a sign,” said he, swinging his club sadly, “have I seen of me little brother from that day on.”

We were patrolling Merlin Street, on the East Side, together, one night when he first told me the story. I was the smallest of all possible reporters on The Manhattan Daily Chronicle at the time, and my most important duty was to cover the Windle Market police-station, which is within a stone’s throw of Merlin Street. It was there that I had met Michael; and when matters were quiet at the station, I would accompany him on his beat, and we would talk of many things, but principally of his little brother Tim. As the days went on, I must have heard the story fifty times. In the telling it sometimes varied, according to Michael’s mood. Sometimes it would be long and unrestrainedly pathetic. At other times it would have all the brevity of an official report. But it always ended in the same way. “And divil a sign,” Mike would say, “have I seen of me little brother from that time on.”

My imagination got to work on the thing. I liked Michael, and the contrast between his words and his granite, expressionless face appealed to me. It was not long before I began to build up in my mind’s eye a picture of the vanished Tim. Each night some remark of Mike’s would add another touch to the portrait. Why I got the idea that Tim was delicate I do not know. I suppose it came from Mike’s insistence on the epithet “little.” At any rate, Tim to me was a slightly-built boy, curly-haired, blue-eyed and pale. Not unlike little Lord Fauntleroy, grown up. Sometimes he had a cough.

There were nights in the hot weather when Mike would be despondent. A New York summer night does not encourage optimism. Tim was dead. He was sure of it. He had made inquiries and had found that a Timothy Bourke, released from Ellis Island at about that time, had found employment helping to construct the Subway. “This Timothy Bourke, working in compressed air in casement under the water, had taken that horrible form of paralysis known as the “bends,” and had died.

“They spelt the name different,” said Mike. “There was an ‘o’ to it, which there isn’t to Burke; but it’s me little brother for all that.” And from this conviction he was not to be shaken for a whole fortnight, till one evening the skies were torn by a thunderstorm and for the space of two hours New York became a shower-bath. And with the cool spell that followed Mike’s optimism came back to him.

It was in the fall that the great thing happened. I am bound to say that by that time I had become as hopeless of setting eyes on Tim in the flesh as ever Mike in his gloomiest moments had been. The better I became acquainted with New York, the more was I impressed with the vastness of the place and the impossibility of finding a man who has disappeared in such a jungle of humanity. New York is not like London. There is no one spot in it which everyone must visit. In London, it has well been said, if you want a man, you may go to Charing Cross and wait. You may have to wait a long time, but sooner or later he will come. New York has no Charing Cross.

My heart was sore for Mike—sorest when he was the most cheerful and talked of the great times he and Tim would have together when they met. It hurt me to hear him talk. Tim was dead—I knew it.

And then one night we found him, without the slightest difficulty. It was as if Fate, conscience-stricken, had resolved that there should be no chance of our overlooking him, for he came to us heralded by the loudest shouts I had ever heard from human throat. Mike and I were walking slowly up Merlin Street, Mike deep in an anecdote of his little brother’s childhood, when suddenly from around the corner in Blake Street there came to us the first of those giant yells. Instantly Mike’s mind got back from the interesting past to the equally interesting present. His jaw protruded. He gripped his club more tightly. The yells suggested murder. We rounded the corner at a brisk gallop.

My feelings, when we came in sight and found that it was not a murder, were mixed. As a citizen, I was relieved. As a reporter, I am afraid I was a little disappointed. Things had been quiet at Windle Market of late and there is no doubt that a murder gives a gifted young reporter, anxious to display his powers to an editor who has always shown a touch of skepticism concerning them, a distinct chance. I replaced my notebook in my pocket with a sigh of resignation. The thing was not even a hold-up. Indeed, at first sight it looked more like a convivial meeting of old friends than anything else.

There were two men on the sidewalk. One, short and stout and wearing a derby hat, was engaging in executing a sort of shuffling dance. The other, a gigantic red-haired man, was standing and snapping his fingers. He was bare-headed. There were the ruins of a tall hat on the ground beside him. Apparently in the exuberance of the moment he had thrown it down and jumped on it.

The stout man was the first to catch sight of us. He paused in his dance, and screamed a few words joyfully in German. The other, with another mammoth shout, wheeled round. The light fell on his face. It was a generously-planned face. Nature seemed to have started out with the idea of making two faces and then to have decided to use all the material for one. A vast jaw was its principal feature. This was surmounted by a grin that must have measured many inches. Curiously enough, the man reminded me instantly of someone I knew quite well, though at the moment I could not name him.

Mike had no such uncertainty. With a yell that rivalled the loudest of those we had heard in Merlin Street, he stopped dead, then sprang forward again. “Timmy!” he roared. “Me little brother!”

“Mike!” howled the man. “Saints above us, it’s me darlin’ Micky!”

They met in a hug like two wrestlers, while I stood respectfully on the outskirts, rapidly removing from its place in my portrait gallery that touching Lord Fauntleroy picture of Mike’s little brother which I had been at such pains for the last six months to paint, varnish and frame at my own expense. It was a pretty picture, considered simply as a work of art, but I felt that it was not a good likeness.

Meanwhile, the brothers had disentangled themselves and were bringing their life-histories up-to-date.

“Little did I think,” said Tim admiringly, “to see me darlin’ Micky a cop, in a fine blue uniform an’ all. It’s you that look the handsome boy, Micky. Who’d have thought of me Micky a cop! Praise the day!”

“An’ I’ve bin lookin’ for you Timmy, ivery blessed minute since they siperated us at the island. Young mister man here”—he indicated me with a wave of the hand—“he’ll tell ye that’s the truth. Ivery blessed minute, mornin’ and night, Timmy. Divil a wink of sleep have I had for eighteen months the way I’ve been looking for ye. I thought ye were dead. Timmy me boy. Young mister man here he’ll tell ye that’s the truth. Where have ye bin? What have ye bin doin’?”

“Sure, I’ve bin makin’ me fortune, Micky boy, like I said I would. First thing after leavin’ the island I gets a job as a bar-keep, settin’ up the drinks and throwin’ out the drunks; and wan day in blows Dan Magee—Red Dan Magee, the same which lived across the way in Skibbereen. He blows in and calls for a Wurtzberger. ‘Dan!’ says I, handin’ him the beer and a push in the chest simultaneous. ‘Wurra!’ says he. ‘It’s Timmy Burke or his ghost!’ And, says Dan, he’s made money the time he’s bin livin’ here, and he’s a hotel in a town out West, and I’m to go with him and help him, for ’tis too large for him to look after alone. Off I go, and it’s a fine, large hotel wid the folks jostling wan another in the doorways the way they’re eager to get in, and now Dan’s back to Ireland, lavin’ meself in charge, drawin’ good money. And I’m in New York for a wake’s holiday for rest and me health.”

At this point in the conversation the first jarring note was struck. The little German, who had been hopping round in an agitated manner, evidently anxious to obtain a hearing, burst into speech. He spoke rapidly and gutturally in his native language. The brothers inspected him with grave disapproval. “Aw, g’wan,” said Mike, “talk English.”

The flood of speech continued unchecked. I stepped forward. I am a poor German scholar, but I was able to pick up the main drift of the harangue. “He’s making a complaint,” I said.

“What’s he got to complain about?” said Mike.

The German was now addressing himself directly to me. Something seemed to have told him that I was his link with the representative of the law. Having persuaded him to reduce his speed, I was enabled to follow him more closely.

“It’s about your brother,” I said.

“About Timmy?”

“He says that your brother assaulted him.”

Righteous indignation on the part of Tim. “And it’s meself,” he said, pained, “that did nothing of the kind. I just gave him wan little shake, so as he’d hardly feel it, to stop him when he was tryin’ to run.”

“He says you forced him to dance.”

“And wasn’t I just tryin’ to teach the little man to dance an Irish jig?” demanded Tim warmly.

“Anyhow,” I said, “he wants to make a complaint at the station.”

A look of deep thought and care settled on Mike’s face. In the excitement of the reunion this aspect of the affair had escaped him for the moment. He had sunk the policeman in the brother. He began to look as if he would be compelled to reverse the process.

I pleaded in my best German. I was eloquent, lucid and moving, but without effect. The complainant was obdurate. His feelings had been wounded and nothing would satisfy him but a general adjournment to the police-station.

“I’m sorry,” I said to Mike. “I can’t persuade him. He’s set on it.”

There was an awkward pause. Mike looked at Tim. Tim looked at Mike. I lit a cigarette. The German gesticulated.

“Timmy,” said Mike ruefully, “it’s pinchin’ ye I’ll have to be after.”

There was another pause.

“Will ye be comin’ along, Timmy boy?” said Mike.

His little brother was obviously struggling with his feelings. He looked from Mike to the ground and back again at Mike. His twiddling fingers betokened agitation of mind. He grinned furtively at intervals. Then he unbosomed himself. “Micky,” he said solemnly, “this is the way ut is. If ye ask ut of me as a brother, I’ll go as quiet as Mary’s lamb. But I tell ye,” he proceeded with pathos, “it cuts me to the heart. Wasn’t I lookin’ to end me evening with the father and mother of a fight with some fool of a cop who’d give me all the fight I wanted? Faith, I haven’t so much as slapped a man since I left Red Dan’s hotel in Wistaria. I tell ye, Micky boy, it’s hard. But if ye ask ut of me as a brother, I’ll do ut. But it’s hard. Bad days to ye, ye small sawn-off, for spoilin’ a man’s pleasure,” he concluded, eyeing the little German reproachfully. “Which way do we go, Micky boy?”

And then Michael rose to the situation like a hero. He sank his private feelings in order to give his little brother pleasure. Tim was the type of Irishman to whom a fight at any hour of the day is meat and drink, regardless of the identity of his opponent. He would have fought his dearest friend for pure love of the thing. But Mike was differently constituted. He was something of a sentimentalist, and a fight with his brother was by no means necessary to his happiness. But he did not hesitate.

“Timmy,” he said, handing me his club, “ye shan’t have your pleasure spoiled. Ye shan’t come quiet. I’d take shame to presume on yer kind heart. Young mister man here can see fair, and I’ll just be the plain cop and give ye all the fight you need.”

“Micky boy,” said Tim, deeply moved, “ye’re a jool.”

Tim apparently favoured the hurricane style of fighting. He rushed in with a whoop, and was hit out again with a drive under the chin. He gulped once or twice. “Faith,” he said, “I thought me head was off. Ye’ve a fine, strong left, Micky boy.”

“Ye want to watch for it comin’ up sudden when ye swing,” said Mike. “Ye never would trouble about your guard, Timmy,” he went on, more in sorrow than in anger. “If I told ye wance about it in the old day, I told ye a thousand times.”

They circled warily round one another, sparring for an opening.

“I had ut from Dan Magee,” said Tim conversationally, parrying a left hook, “that little Kate Malone is married this eight months.”

“She is?” said Mike, interested, swinging with his right, and missing. “Who’s the boy?”

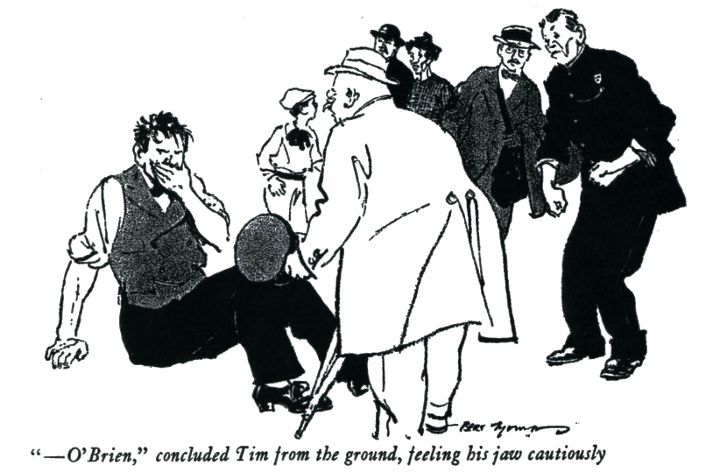

“Larry”—Tim broke off to rush in and try a double lead and a right to the body; Mike scored the first knockdown with an upper-cut; “—O’Brien,” concluded Tim from the ground, feeling his jaw cautiously.

“Larry O’Brien! Ye don’t say! Have ye had enough, Timmy boy?”

“I should like more,” said Tim wistfully, “if ut isn’t incommodin’ you, Micky.”

“Sure, no,” said Mike heartily, “take all you want.”

“Thank ye, Micky boy.”

“An’ look out for me left that comes up when we’re in-fightin’,” said Mike, with brotherly solicitude.

“I’ll remember ut. Ready, Micky?”

“Sure!”

Round two began.

“Murphy’s dead,” said Tim.

Mike side-stepped. “Which Murphy?” he asked.

“Old Jack Murphy,” said Tim, landing heavily on his brother’s left ear.

“Old Jack Murphy who had the duck-farm?”

“That’s the man. He died of fallin’ downstairs in the dark and breakin’ his neck.”

“Poor old Jack,” said Mike, sorrowfully hammering Tim’s ribs.

“All flesh is as grass,” said Tim philosophically as he went down for the second time.

It was in the middle of the third round that the end came. It was the briskest of the three, and for the first minute I thought that Tim would recover the ground he had lost in the opening stages. Twice he staggered Mike with right swings, but his fatal passion for imparting news undid him. In the excitement of telling the story of the love-affairs of a certain Andy Regan, as related to him by Dan Magee, he had the misfortune to leave exposed that portion of the anatomy known as the solar plexus. Mike’s left shot out, and the anecdote ended in a gasp and a gurgle, as the narrator sank slowly and peacefully to the ground.

Mike wiped his brow and looked deprecatingly at me. “Ye mustn’t think me little brother can’t fight,” he said. “He’s a rale good boy, if he wasn’t so careless. Boy and man he never would remember to kape watch over his body, the way it wouldn’t get jolted by a blow. But for all I’ve beaten him, don’t you think, young mister man, as me little brother isn’t a rale good fighter. He’s careless, that’s all. Are ye feelin’ better, Timmy boy? Have ye had enough?”

“Thank ye, Micky, yes. I’d go on, but I doubt me I can’t stand. I’m rale sorry to spoil your pleasure this early, but me legs will not hold me. Lift me up aisy, Micky boy, and help me to the station.”

P. G. Wodehouse.

Madame Eulalie’s Rare Plums

Madame Eulalie’s Rare Plums