The Saturday Evening Post, December 26, 1925

“ LIFE, laddie,” said Ukridge, “is very rum.” He had been lying for some time silent on the sofa, his face toward the ceiling; and I had supposed that he was asleep. But now it appeared that it was thought that had caused his unwonted quietude.

“Very, very rum,” said Ukridge. He heaved himself up and stared out of the window. The sitting-room window of the cottage which I had taken in the country looked upon a stretch of lawn, backed by a little spinney; and now there stole in through it from the waking world outside that first cool breeze which heralds the dawning of a summer day.

“Great Scott!” I said, looking at my watch. “Do you realize you’ve kept me up talking all night?”

Ukridge did not answer. There was a curious, far-away look on his face, and he uttered a sound like the last gurgle of an expiring soda-water siphon, which I took to be his idea of a sigh.

I saw what had happened. There is a certain hour at the day’s beginning which brings with it a strange magic, tapping wells of sentiment in the most hard-boiled. In this hour, with the sun pinking the eastern sky and the early bird chirping over its worm, Stanley Featherstonehaugh Ukridge, that battered man of wrath, had become maudlin; and, instead of being allowed to go to bed, I was in for some story of his murky past.

“Extraordinarily rum,” said Ukridge. “So is fate. It’s curious to think, Corky, old horse, that if things had not happened as they did I might now be a man of tremendous importance, looked up to and respected by all in Singapore.”

“Why should anyone respect you in Singapore?”

“Rolling in money,” proceeded Ukridge wistfully.

“You?”

“Yes, me. Did you ever hear of one of those blokes out East who didn’t amass a huge fortune? Of course you didn’t. Well, think what I should have done, with my brain and vision. Mabel’s father made a perfect pot of money in Singapore and I don’t suppose he had any vision whatsoever.”

“Who was Mabel?”

“Haven’t I ever spoken to you of Mabel?”

“No. Mabel who?”

“I won’t mention names.”

“I hate stories without names.”

“You’ll have this story without names—and like it,” said Ukridge with spirit. He sighed again. A most unpleasant sound. “Corky, my boy,” he said, “do you realize on what slender threads our lives hang? Do you realize how trifling can be the snags on which we stub our toes as we go through this world? Do you realize ——”

“Get on with it.”

“In my case it was a top hat.”

“What was a top hat?”

“The snag.”

“You stubbed your toe on a top hat?”

“Figuratively, yes. It was a top hat which altered the whole course of my life.”

“You never had a top hat.”

“Yes, I did have a top hat. It’s absurd for you to pretend that I never had a top hat. You know perfectly well that when I go to live with my Aunt Julia in Wimbledon I roll in top hats—literally roll.”

“Oh, yes, when you go to live with your aunt.”

“Well, it was when I was living with her that I met Mabel. The affair of the top hat happened ——”

I looked at my watch again.

“I can give you half an hour,” I said. “After that I’m going to bed. If you can condense Mabel into a thirty-minute sketch, carry on.”

“This is not quite the sympathetic attitude I would like to see in an old friend, Corky.”

“It’s the only attitude I’m capable of at half past three in the morning. Snap into it.”

Ukridge pondered.

“It’s difficult to know where to begin.”

“Well, to start with, who was she?”

“She was the daughter of a bloke who ran some sort of immensely wealthy business in Singapore.”

“Where did she live?”

“In Onslow Square.”

“Where were you living?”

“With my aunt in Wimbledon.”

“Where did you meet her?”

“At a dinner party at my aunt’s.”

“You fell in love with her at first sight?”

“Yes.”

“For a while it seemed she might return your love?”

“Exactly.”

“And then one day she saw you in a top hat and the whole thing was off. There you are. The entire story in two minutes, fifteen seconds. Now let’s go to bed.”

Ukridge shook his head.

“You’ve got it wrong, old horse. Nothing like that at all. You’d better let me tell the whole thing from the beginning.”

The first thing I did after that dinner—said Ukridge—was to go and call at Onslow Square. As a matter of fact, I called about three times in the first week; and it seemed to me that everything was going like a breeze. You know what I’m like when I’m staying with my Aunt Julia, Corky. Dapper is the word. Debonair. Perfectly groomed. Mind you, I don’t say I enjoy dressing the way she makes me dress when I’m with her, but there’s no getting away from it that it gives me an air. Seeing me strolling along the street with the gloves, the cane, the spats, the shoes and the old top hat, you might wonder if I was a marquis or a duke, but you would be pretty sure I was one of the two.

These things count with a girl. They count still more with her mother. By the end of the second week you wouldn’t be far wrong in saying that I was the popular pet at Onslow Square. And then, rolling in one afternoon for a dish of tea, I was shocked to perceive nestling in my favorite chair, with all the appearance of a cove who is absolutely at home, another bloke. Mabel’s mother was fussing over him as if he were the long-lost son. Mabel seemed to like him a good deal. And the nastiest shock of all came when I discovered that the fellow was a baronet.

Now, you know as well as I do, Corky, that for the ordinary workaday bloke barts are tough birds to go up against. There is something about barts that appeals to the most soulful girl. And, as for the average mother, she eats them alive. Even an elderly bart with two chins and a bald head is bad enough, and this was a young and juicy specimen. He had a clean-cut, slightly pimply, patrician face; and, what was worse, he was in the Coldstream Guards. And you will bear me out, Corky, when I say that, while an ordinary civilian bart is bad enough, a bart who is also a guardee is a rival the stoutest-hearted cove might well shudder at.

And when you consider that practically all I had to put up against this serious menace was honest worth and a happy disposition, you will understand why the brow was a good deal wrinkled as I sat sipping my tea and listening to the rest of the company talking about people I’d never heard of and entertainments where I hadn’t been among those we also noticed.

After a while the conversation turned to Ascot.

“Are you going to Ascot, Mr. Ukridge?” said Mabel’s mother, apparently feeling that it was time to include me in the chitchat.

“Wouldn’t miss it for worlds,” I said.

Though, as a matter of fact, until that moment I had rather intended to give it the go-by. Fond as I am of the sport of kings, to my mind a race meeting where you’ve got to go in a morning coat and a top hat—with the thermometer probably in the nineties—lacks fascination. I’m all for being the young duke when occasion requires, but races and toppers don’t seem to me to go together.

“That’s splendid,” said Mabel, and I’m bound to say these kind words cheered me up a good deal. “We shall meet there.”

“Sir Aubrey,” said Mabel’s mother, “has invited us to his house party.”

“Taken a place for the week down there,” explained the bart.

“Ah!” I said. And, mark you, that was about all there was to say. For the sickening realization that this guardee bart, in addition to being a bart and a guardee, also possessed enough cash to take country houses for Ascot Week in that careless, offhand manner, seemed to go all over me like nettle rash. I was rattled, Corky. Your old friend was rattled. I did some pretty tense thinking on my way back to Wimbledon.

When I got there, I found my aunt in the drawing-room. And suddenly something in her attitude seemed to smite me like a blow. I don’t know if you have ever had that rummy feeling which seems to whisper in your ear that hell’s foundations are about to quiver, but I got it the moment I caught sight of her. She was sitting bolt upright in a chair, and as I came in she looked at me. You know her, Corky, and you know just how she shoots her eyes at you without turning her head, as if she were a basilisk with a stiff neck. Well, that’s how she looked at me now.

“Good evening,” she said.

“Good evening,” I said.

“So you’ve come in,” she said.

“Yes,” I said.

“Well, then, you can go straight out again,” she said.

“Eh?” I said.

“And never come back,” she said.

I goggled at her. Mark you, I had been heaved out of the old home by my Aunt Julia many a time before, so it wasn’t as if I wasn’t used to it; but I had never got the boot quite so suddenly before and so completely out of a blue sky. Usually, when Aunt Julia bungs me out on my ear, it is possible to see it coming days ahead.

“I might have guessed that something like this would happen,” she said.

And then all things were made plain. She had found out about the clock. And it shows what love can do to a fellow, Corky, when I tell you that I had clean forgotten all about it.

You know the position of affairs when I go to live with my Aunt Julia. She feeds me and buys me clothes, but for some reason best known to her own distorted mind it is impossible to induce her to part with a little ready cash. The consequence was that, falling in love with Mabel as I had done and needing a quid or two for current expenses, I had had to rely on my native ingenuity and resources. It was absolutely imperative that I should give the girl a few flowers and chocolates from time to time, and this runs into money. So, seeing a rather juicy clock doing nothing on the mantelpiece of the spare bedroom, I had sneaked it off under my coat and put it up the spout at the local pawnbroker’s. And now, apparently, in some devious and underhand manner she had discovered this.

Well, it was no good arguing. When my Aunt Julia is standing over you with her sleeves rolled up preparatory to getting a grip on the scruff of your neck and the seat of your trousers, it has always been my experience that words are useless. The only thing to do is to drift away and trust to time, the great healer. Some forty minutes later, therefore, a solitary figure might have been observed legging it to the station with a suitcase. I was out in the great world once more.

However, you know me, Corky. The old campaigner. It takes more than a knock like that to crush your old friend. I took a bed-sitting room in Arundel Street and sat down to envisage the situation.

Undeniably things had taken a nasty twist, and many a man lacking my vision and enterprise might have turned his face to the wall and said, “This is the end.” But I am made of sterner stuff. It seemed to me that all was not yet over. I had packed the morning coat, the waistcoat, the trousers, the shoes, the spats and the gloves, and had gone away wearing the old top hat; so, from a purely ornamental point of view, I was in precisely the position I had been before. That is to say, I could still continue to call at Onslow Square; and, what is more, if I could touch George Tupper for a fiver—which I intended to do without delay—should have the funds to go to Ascot.

The sun, it appeared to me, therefore, was still shining. How true it is, Corky, that no matter how the tempests lower there is always sunshine somewhere. How true it is—oh, all right. I was only mentioning it.

Well, George Tupper, splendid fellow, parted without a murmur. Well, no, not—to be absolutely accurate—without a murmur. Still, he parted. And the position of affairs was now as follows: Cash in hand, five pounds. Price of admission to grand stand and paddock at Ascot for first day of meeting, two pounds. Time to elapse before Ascot, ten days. Net result—three quid in my kick to keep me going till then and pay my fare down and buy flowers and so on. It all looked very rosy.

But note, Corky, how Fate plays with us. Two days before Ascot, as I was coming back from having tea at Onslow Square—not a little preoccupied, for the bart had been very strong on the wing that afternoon—there happened what seemed at first sight an irremediable disaster.

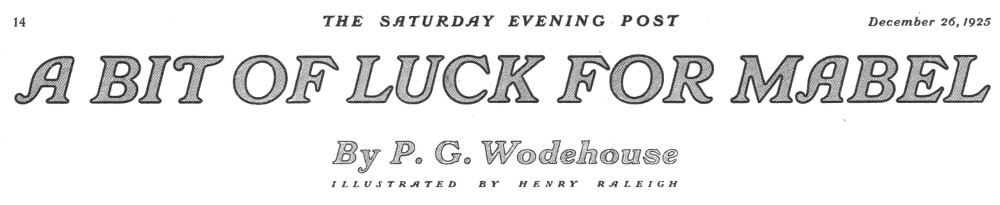

The weather, which had been fair and warm until that evening, had suddenly broken, and a rather nippy wind had sprung up from the east. Now, if I had not been so tensely occupied with my thoughts, brooding on the bart, I should, of course, have exercised reasonable precautions; but, as it was, I turned the corner into the Fulham Road in what you might call a brown study; and the first thing I knew my top hat had been whisked off my head and was tooling along briskly in the direction of Putney.

Well, you know what the Fulham Road’s like. A top hat has about as much chance in it as a rabbit at a dog show. I dashed after the thing with all possible speed, but what was the use? A taxicab knocked it sideways toward a bus, and the bus, curse it, did the rest. By the time the traffic had cleared a bit, I caught sight of the ruins and turned away with a silent groan. The thing wasn’t worth picking up.

So there I was, dished.

Or, rather, what the casual observer who didn’t know my enterprise and resource would have called dished. For a man like me, Corky, may be down, but he is never out. So swift were my mental processes that the time that elapsed between the sight of that ruined hat and my decision to pop round to the Foreign Office and touch George Tupper for another fiver was not more than fifty seconds. It is in the crises of life that brains really tell.

You can’t accumulate if you don’t speculate. So, though funds were running a bit low by this time, I invested a couple of bob in a cab. It was better to be two shillings out than to risk getting to the Foreign Office and finding that Tuppy had left.

Well, late though it was, he was still there. That’s one of the things I like about George Tupper, one of the reasons why I always maintain that he will rise to impressive heights in his country’s service—he does not shirk; he is not a clock watcher. Many civil servants are apt to call it a day at five o’clock, but not George Tupper. That is why one of these days, Corky, when you are still struggling along turning out articles for Interesting Bits and writing footling short stories about girls who want to be loved for themselves alone, Tuppy will be Sir George Tupper, K. C. M. G., and a devil of a fellow among the chancelleries.

I found him up to his eyes in official-looking papers, and I came to the point with all speed. I knew that he was probably busy declaring war on Montenegro or somewhere and wouldn’t want a lot of idle chatter.

“Tuppy, old horse,” I said, “it is imperative that I have a fiver immediately.”

“A what?” said Tuppy.

“A tenner,” I said.

It was at this point that I was horrified to observe in the man’s eye that rather cold, forbidding look which you sometimes see in blokes’ eyes on these occasions.

“I lent you five pounds only a week ago,” he said.

“And may heaven reward you, old horse,” I replied courteously.

“What do you want any more for?”

I was just about to tell him the whole circumstances when it was as if a voice whispered to me, “Don’t do it!” Something told me that Tuppy was in a nasty frame of mind and was going to turn me down—yes, me, an old schoolfellow, who had known him since he was in Eton collars. And at the same time I suddenly perceived, lying on a chair by the door, Tuppy’s topper. For Tuppy is not one of those civil servants who lounge into Whitehall in flannels and a straw hat. He is a correct dresser, and I honor him for it.

“What on earth,” said Tuppy, “do you need money for?”

“Personal expenses, laddie,” I replied. “The cost of living is very high these days.”

“What you want,” said Tuppy, “is work.”

“What I want,” I reminded him—if old Tuppy has a fault, it is that he will not stick to the point—“is a fiver.”

He shook his head in a way I did not like to see.

“It’s very bad for you, all this messing about on borrowed money. It’s not that I grudge it to you,” said Tuppy; and I knew, when I heard him talk in that pompous, foreign-official way, that something had gone wrong that day in the country’s service. Probably the draft treaty with Switzerland had been pinched by a foreign adventuress. That sort of thing is happening all the time in the Foreign Office. Mysterious veiled women blow in on old Tuppy and engage him in conversation, and when he turns round he finds the long blue envelope with the important papers in it gone.

“It’s not that I grudge you the money,” said Tuppy, “but you really ought to be in some regular job. I must think,” said Tuppy. “I must think. I must have a look round.”

“And meanwhile,” I said, “the fiver?”

“No. I’m not going to give it to you.”

“Only five pounds,” I urged. “Five little pounds, Tuppy, old horse.”

“No.”

“You can chalk it up in the books to office expenses and throw the burden on the taxpayer.”

“No.”

“Will nothing move you?”

“No. And I’m awfully sorry, old man, but I must ask you to clear out now. I’m terribly busy.”

“Oh, right-o,” I said.

He burrowed down into the documents again; and I moved to the door, scooped up the top hat from the chair, and passed out.

Next morning, when I was having a bit of breakfast, in rolled old Tuppy.

“I say,” said Tuppy.

“Say on, laddie.”

“You know when you came to see me yesterday?”

“Yes. You’ve come to tell me you’ve changed your mind about that fiver?”

“No, I haven’t come to tell you I’ve changed my mind about that fiver. I was going to say that, when I started to leave the office, I found my top hat had gone.”

“Too bad,” I said.

Tuppy gave me a piercing glance.

“You didn’t take it, I suppose.”

“Who, me? What would I want with a top hat?”

“Well, it’s very mysterious.”

“I expect you’ll find it was pinched by an international spy or something.”

Tuppy brooded for some moments.

“It’s all very odd,” he said. “I’ve never had it happen to me before.”

“One gets new experiences.”

“Well, never mind about that. What I really came about was to tell you that I think I have got you a job.”

“You don’t mean that!”

“I met a man at the club last night who wants a secretary. It’s more a matter with him of having somebody to keep his papers in order and all that sort of thing, so typing and shorthand are not essential. You can’t do shorthand, I suppose.”

“I don’t know. I’ve never tried.”

“Well, you’re to go and see him tomorrow morning at ten. His name’s Bulstrode, and you’ll find him at my club. It’s a good chance, so for heaven’s sake don’t be lounging in bed at ten.”

“I won’t. I’ll be up and ready, with a heart for any fate.”

“Well, mind you are.”

“And I am deeply grateful, Tuppy, old horse, for these esteemed favors.”

“That’s all right,” said Tuppy. He paused at the door. “It’s a mystery about that hat.”

“Insoluble, I should say. I shouldn’t worry any more about it.”

“One moment it was there, and the next it had gone.”

“How like life!” I said. “Makes one think a bit, that sort of thing.”

He pushed off, and I was just finishing my breakfast when Mrs. Beale, my landlady, came in with a letter.

It was from Mabel, reminding me to be sure to come to Ascot. I read it three times while I was consuming a fried egg; and I am not ashamed to say, Corky, that tears filled my eyes. To think of her caring so much that she should send special letters urging me to be there made me tremble like a leaf. It looked to me as though the bart’s number was up. Yes, at that moment, Corky, I felt positively sorry for the bart, who was in his way quite a good chap, though pimply.

That night I made my final preparations. I counted the cash in hand. I had just enough to pay my fare to Ascot and back, my entrance fee to the grand stand and paddock, with a matter of fifteen bob over for lunch and general expenses and a thoughtful ten bob to do a bit of betting with. Financially, I was on velvet.

Nor was there much wrong with the costume department. I dug out the trousers, the morning coat, the waistcoat, the shoes and the spats, and I tried on Tuppy’s topper again. And for the twentieth time I wished that old Tuppy, a man of sterling qualities in every other respect, had had a slightly bigger head. It’s a curious thing about old George Tupper. There’s a man who you might say is practically directing the destinies of a great nation—at any rate, he’s in the Foreign Office and extremely well thought of by the nibs; and yet his size in hats is a small seven. I don’t know if you’ve ever noticed that Tuppy’s head goes up to a sort of point. Mine, on the other hand, is shaped more like a mangel-wurzel, and this made the whole thing rather complex and unpleasant.

As I stood at the glass, giving myself a final inspection, I couldn’t help feeling what a difference a hat makes to a man. Bare-headed, I was perfect in every detail, but with the hat on I looked a good deal like a bloke about to go on and do a comic song at one of the halls. Still, there it was, and it was no good worrying about it. I put the trousers under the mattress to insure an adequate crease, and I rang the bell for Mrs. Beale and gave her the coat to press with a hot iron. I also gave her the hat and instructed her to rub stout on it. This, as you doubtless know, gives a topper the deuce of a gloss, and when a fellow is up against a bart he can’t afford to neglect the smallest detail.

And so to bed.

I didn’t sleep very well. At about one in the morning it started to rain in buckets, and the thought suddenly struck me: What the deuce was I going to do if it rained during the day? To buy an umbrella would simply dislocate the budget beyond repair. The consequence was that I tossed pretty restlessly on my pillow.

But all was well. When I woke at eight o’clock, the sun was pouring into the room and the last snag seemed to have been removed from my path. I had breakfast, and then I dug the trouserings out from under the mattress, slipped into them, put on the shoes, buckled the spats, and rang the bell for Mrs. Beale. I was feeling debonair to a degree. The crease in the trousers was perfect.

“Oh, Mrs. Beale,” I said. “The coat and the hat, please. What a lovely morning!”

Now, this Beale woman, I must tell you, was a slightly sinister sort of female, with eyes that reminded me a good deal of my Aunt Julia’s. And I was now somewhat rattled to perceive that she was looking at me in a rather meaning kind of manner. I also perceived that she held in her hand a paper or document. And there shot through me, Corky, a nameless fear. It’s a kind of instinct, I suppose. A man who has been up against it as frequently as I have comes to shudder automatically when he sees a landlady holding a sheet of paper and looking at him in a meaning manner. A moment later it was plain that my sixth sense had not deceived me.

“I’ve brought your little account, Mr. Ukridge,” said this fearful female.

“Right!” I said heartily. “Just shove it on the table, will you. And bring the coat and hat.”

She looked more like my Aunt Julia than ever.

“I must ask you for the money now,” she said. “Being a week overdue.”

All this was taking the sunshine out of the morning, but I remained debonair.

“Yes, yes,” I said. “I quite understand. We’ll have a good long talk about that later. The hat and coat, please, Mrs. Beale.”

“I must ask you”—she was beginning again, but I checked her with one of my looks. If there’s one thing I bar in this world, Corky, it’s sordidness.

“Yes, yes,” I said testily. “Some other time. I want the hat and coat, please.”

At this moment, by the greatest bad luck, her vampire gaze fell on the mantelpiece. You know how it is when you are dressing with unusual care—you fill your pockets last thing. And I had most unfortunately placed my little capital on the mantelpiece. Too late I saw that she had spotted it. Take the advice of a man who has seen something of life, Corky, and never leave your money lying about. It’s bound to start a disagreeable train of thought in the mind of anyone who sees it.

“You’ve got the money there,” said Mrs. Beale.

I leaped for the mantelpiece and trousered the cash.

“No, no,” I said hastily. “You can’t have that. I need that.”

“Ho?” she said. “So do I.”

“Now listen, Mrs. Beale,” I said. “You know as well as I do ——”

“I know as well as you do that you owe me two pounds three and sixpence ha’penny.”

“And in good time,” I said, “you shall have it. But just for the moment you must be patient. Why, dash it, Mrs. Beale,” I said warmly, “you know as well as I do that in all financial transactions a certain amount of credit is an understood thing. Credit is the lifeblood of commerce. Without credit commerce has no elasticity. So bring the hat and coat, and later on we will thresh this matter out thoroughly.”

And then this woman showed a baseness of soul, a horrible low cunning which, I like to think, is rarely seen in the female sex.

“I’ll either have the money,” she said, “or I’ll keep the coat and hat.” And words cannot express, Corky, the hideous malignity in her voice. “They ought to fetch a bit.”

I stared at her, appalled.

“But I can’t go to Ascot without a top hat.”

“Then you’d better not go to Ascot.”

“Be reasonable!” I begged. “Reflect!”

It was no good. She stood firm on her demand for two pounds three and sixpence ha’penny.

It is only when you are in a situation like that, Corky, that you really begin to be able to appreciate the true hollowness of the world. This Ascot business, for instance. Why should it be necessary to wear a top hat at Ascot, when you can go to all the other races in anything you like?

Here was I, perfectly equipped for Hurst Park, Sandown, Gatwick, Ally Pally, Lingfield or any other meeting you care to name; and, simply because a ghoul of a landlady had pinched my topper, I was utterly debarred from going to Ascot, though the price of admission was bulging in my pocket. It’s just that sort of thing that makes a fellow chafe at our modern civilization and wonder if after all man can be Nature’s last word.

Such, Corky, were my meditations as I stood at the window and gazed bleakly out at the sunshine. And then, suddenly, as I gazed, I observed a bloke approaching up the street.

I eyed him with interest. He was an elderly, prosperous bloke with a yellowish face and a white mustache, and he was looking at the numbers on the doors as if he was trying to spot a destination. And at this moment he halted outside the front door of my house, squinted up at the number, and then trotted up the steps and rang the bell. And I realized at once that this must be Tuppy’s secretary man, the fellow I was due to go and see at the club in another half hour. For a moment it seemed odd that he should have come to call on me instead of waiting for me to call on him; and then I reflected that this was just the sort of thing that the energetic, world’s-worker type of man that Tuppy chummed up with at his club would be likely to do. Time is money with these coves, and no doubt he had remembered some other appointment which he couldn’t make if he waited at his club till ten.

Anyway, here he was, and I peered down at him with a beating heart. For what sent a thrill through me, Corky, was the fact that he was much about my build and was brightly clad in correct morning costume, with top hat complete. And though it was hard to tell exactly at such a distance and elevation, the thought flashed across me like an inspiration from above that that top hat would fit me a dashed sight better than Tuppy’s had done. In another minute there was a knock on the door, and he came in. Seeing him at close range, I perceived that I had not misjudged this man. He was shortish, but his shoulders were just about the same size as mine, and his head was large and round. If ever, in a word, a bloke might have been designed by Providence to wear a coat and hat that would fit me, this bloke was that bloke. I gazed at him with a gleaming eye.

“Mr. Ukridge?”

“Yes,” I said. “Come in. Awfully good of you to call.”

“Not at all.”

And now, Corky, as you will no doubt have divined, I was, so to speak, at the crossroads. The finger post of prudence pointed one way, that of love another. Prudence whispered to me to conciliate this bloke, to speak him fair, to comport myself toward him as toward one who held my destinies in his hand and who could, if well disposed, give me a job which would keep the wolf from the door while I was looking round for something bigger and more attuned to my vision and abilities.

Love, on the other hand, was shouting to me to pinch his coat and hat and leg it for the open spaces.

It was the deuce of a dilemma.

“I have called ——” began the bloke.

I made up my mind. Love got the decision.

“I say,” I said, “I think you’ve got something on the back of your coat.”

“Eh?” said the bloke, trying to squint round and look between his shoulder blades—silly ass.

“It’s a squashed tomato or something.”

“A squashed tomato?”

“Or something.”

“How would I get a squashed tomato on my coat?”

“Ah!” I said, giving him to understand with a wave of the hand that these were deep matters.

“Very curious,” said the bloke.

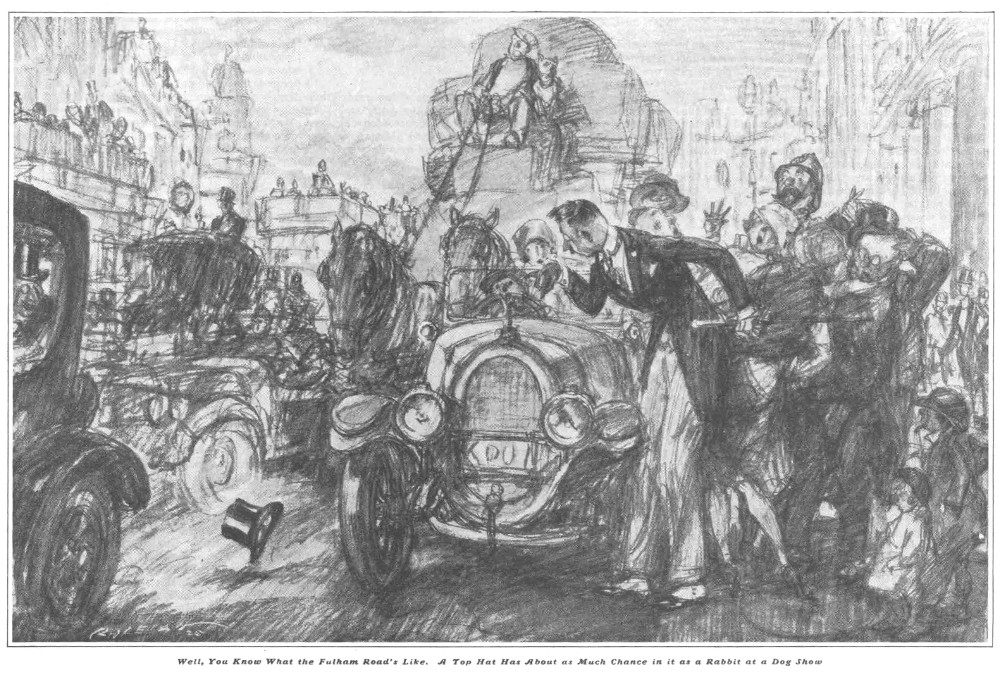

“Very,” I said. “Slip off your coat and let’s have a look at it.”

He slid out of the coat and I was on it like a knife. You have to move quick on these occasions, and I moved quick. I had the coat out of his hand and the top hat off the table where he had put it, and was out of the door and dashing down the stairs before he could utter a yip. I put on the coat and it fitted like a glove. I slapped the top hat onto my head, and it might have been made for me. And then I went out into the sunshine, as natty a specimen as ever paced down Piccadilly.

I was passing down the front steps when I heard a sort of bellow from above. There was the bloke, protruding from the window; and, strong man though I am, Corky, I admit that for an instant I quailed at the sight of the hideous fury that distorted his countenance.

“Come back!” shouted the bloke.

Well, it wasn’t a time for standing and making explanations and generally exchanging idle chatter. When a man is leaning out of window in his shirt sleeves making the amount of noise that this cove was making, it doesn’t take long for a crowd to gather. And my experience has been that when a crowd gathers, it isn’t much longer before some infernal, officious policeman rolls round as well. Nothing was further from my wishes than to have this little purely private affair between the bloke and myself sifted by a policeman in front of a large crowd. So I didn’t linger. I waved my hand as much as to say that all would come right in the future, and then I nipped at a fairly high rate of speed round the corner and hailed a taxi. It had been no part of my plans to incur the expense of a taxi, I having earmarked twopence for a ride on the Tube to Waterloo; but there are times when economy is false prudence.

Once in the cab, whizzing along and putting more distance between the bloke and myself with every revolution of the wheels, I perked up amazingly. I had been, I confess, a trifle apprehensive until now; but from this moment everything seemed splendid. I forgot to mention it before, but this final top hat which now nestled so snugly on the brow was a gray top hat; and, if there is one thing that really lends a zip and a sort of devilish fascination to a fellow’s appearance, it is one of those gray toppers. As I looked at myself in the glass and then gazed out of the window at the gay sunshine, it seemed to me that God was in his heaven and all right with the world.

The general excellence of things continued. I had a pleasant journey; and, when I got to Ascot, I planked my ten bob on a horse I had heard some fellows talking about in the train, and, by Jove, it ambled home at a crisp ten to one. So there I was, five quid ahead of the game almost, you might say, before I had got there. It was with an uplifted heart, Corky, that I strolled off to the paddock to have a look at the multitude and try to find Mabel. And I had hardly emerged from that tunnel thing that you have to walk through to get from the stand, to the paddock when I ran into old Tuppy.

My first feeling on observing the dear old chap was one of relief that I wasn’t wearing his hat. Old Tuppy is one of the best, but little things are apt to upset him and I was in no mood for a painful scene.

“Ah, Tuppy,” I said genially.

George Tupper is a man with a heart of gold, but he is deficient in tact.

“How the deuce did you get here?” he asked.

“In the ordinary way, laddie,” I said.

“I mean, what are you doing here dressed up to the nines like this?”

“Naturally,” I replied with a touch of stiffness, “when I come to Ascot, I wear the accepted morning costume of the well-dressed Englishman.”

“You look as if you had come into a fortune.”

“Yes?” I said, rather wishing he would change the subject. In spite of what you might call the perfect alibi of the gray topper, I did not want to discuss hats and clothes with Tuppy so soon after his recent bereavement. I could see that the hat he had on was a brand new one and must have set him back at least a couple of quid.

“I suppose you’ve gone back to your aunt?” said Tuppy, jumping at a plausible solution. “Well, I’m awfully glad, old man, because I’m afraid that secretary job is off. I was going to write to you tonight.”

“Off?” I said. Having had the advantage of seeing the bloke’s face as he hung out of the window at the moment of our parting, I knew it was off, but I couldn’t see how Tuppy could know.

“He rang me up last night to tell me that he was afraid you wouldn’t do, as he had decided that he must have a secretary who knew shorthand.”

“Oh!” I said. “Oh, did he? Then I’m dashed glad,” I said warmly, “that I pinched his hat. It will be a sharp lesson to him not to raise people’s hopes and shilly-shally in this manner.”

“Pinched his hat? What do you mean?”

I perceived that there was need for caution. Tuppy was looking at me in an odd manner, and I could see that the turn the conversation had taken was once more wakening in him suspicions that he ought to have known better than to entertain of an old school friend.

“It was like this, Tuppy,” I said. “When you came to me and told me about that international spy sneaking your hat from the Foreign Office, it gave me an idea. I had been wanting to come to Ascot, but I had no topper. Of course, if I had pinched yours, as you imagined for a moment I had done, I should have had one; but, not having pinched yours, of course I hadn’t one. So when your friend Bulstrode called on me this morning I collared his. And now that you have revealed to me what a fickle, changeable character he is, I’m very glad I did.”

Tuppy gaped slightly.

“Bulstrode called on you this morning, did you say?”

“This morning at about half-past nine.”

“He couldn’t have done.”

“Then how do you account for my having his hat? Pull yourself together, Tuppy, old horse.”

“The man who came to see you couldn’t have been Bulstrode.”

“Why not?”

“He left for Paris last night.”

“What!”

“He phoned me from the station just before his train started. He had had to change his plans.”

“Then who was the bloke?” I said. The thing seemed to me to have the makings of one of those great historic mysteries you read about. I saw no reason why posterity should not discuss forever the problem of the Bloke in the Gray Topper as keenly as they do the Man in the Iron Mask. “The facts,” I said, “are precisely as I have stated. At nine-thirty this morning a bird, gayly appareled in morning coat, sponge-bag trousers and gray top hat presented himself at my rooms and——”

At this moment a voice spoke behind me.

“Oh, hullo!”

I turned, and observed the bart.

“Hullo!” I said.

I introduced Tuppy. The bart nodded courteously.

“I say,” said the bart. “Where’s the old man?”

“What old man?”

“Mabel’s father. Didn’t he catch you?”

I stared at the man. He appeared to me to be gibbering. And a gibbering bart is a nasty thing to have hanging about you before you have strengthened yourself with a bit of lunch.

“Mabel’s father’s in Singapore,” I said.

“No, he isn’t,” said the bart. “He got home yesterday, and Mabel sent him round to your place to pick you up and bring you down here in the car. Had you left before he arrived?”

Well, that’s where the story ends, Corky. From the moment that pimply baronet uttered those words, you might say that I faded out of the picture. I never went near Onslow Square again. Nobody can say that I lack nerve, but I hadn’t nerve enough to creep into the family circle and resume acquaintance with that fearsome bloke. There are some men, no doubt, with whom I might have been able to pass the whole thing off with a light laugh, but that glimpse I had had of him as he bellowed out of the window told me that he was not one of them. I faded away, Corky, old horse, just faded away. And about a couple of months later I read in the paper that Mabel had married the bart.

Ukridge sighed another sigh and heaved himself up from the sofa. Outside, the world was blue-gray with the growing dawn, and even the later birds were busy among the worms.

“You might make a story out of that, Corky,” said Ukridge.

“I might,” I said.

“All profits to be shared on a strict fifty-fifty basis, of course.”

“Of course.”

Ukridge brooded.

“Though it really wants a bigger man to do it justice and tell it properly, bringing out all the fine shades of the tragedy. It wants somebody like Thomas Hardy or Kipling or somebody.”

“Better let me have a shot at it.”

“All right,” said Ukridge. “And, as regards a title, I should call it His Lost Romance or something like that. Or would you suggest simply something terse and telling like Fate or Destiny?”

“I’ll think of a title,” I said.

Madame Eulalie’s Rare Plums

Madame Eulalie’s Rare Plums