The Saturday Evening Post, July 3, 1915

III—(Continued)

THE reason why all we novelists with bulging foreheads and expensive college educations are abandoning novels and taking to writing motion-picture scenarios is that the latter are so infinitely more simple and pleasant. If this narrative, for instance, were a film drama the operator at this point would flash on the screen the words:

Mr. Peters Discovers the Loss of the Scarab

And for a brief moment the audience would see an interior set, in which a little angry man, with a sharp face and starting eyes, would register, first, discovery; next, dismay.

The whole thing would be over in an instant. The printed word demands a greater elaboration.

It was Aline Peters who had to bear the brunt of her father’s mental agony when he discovered, shortly after Lord Emsworth had left him, that the gem of his collection of scarabs had done the same. It is always the innocent bystander who suffers.

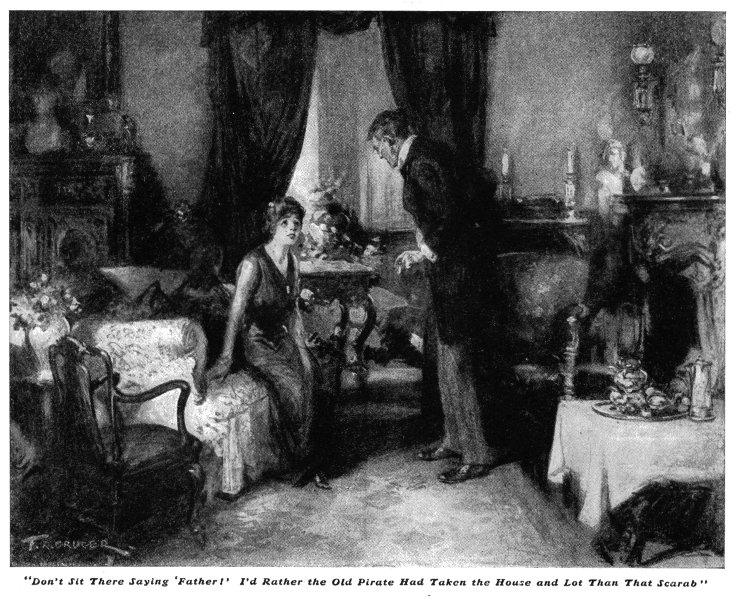

“The darned old sneak thief!” said Mr. Peters.

“Father!”

“Don’t sit there saying Father!’ What’s the use of saying Father!’? Do you think it is going to help—your saying Father!’? I’d rather the old pirate had taken the house and lot than that scarab. He knows what’s what! Trust him to walk off with the pick of the whole bunch! I did think I could trust the father of the man who’s going to marry my daughter for a second alone with the things. There’s no morality among collectors—none! I’d trust a syndicate of Jesse James, Captain Kidd and Dick Turpin sooner than I would a collector. My Cheops of the Fourth Dynasty! I wouldn’t have lost it for five thousand dollars!”

“But, father, couldn’t you write him a letter, asking for it back? He’s such a nice old man! I’m sure he didn’t mean to steal the scarab.”

Mr. Peters’ overwrought soul blew off steam in the shape of a passionate snort.

“Didn’t mean to steal it! What do you think he meant to do—take it away and keep it safe for me for fear I should lose it? Didn’t mean to steal it! I bet you he’s well-known in society as a kleptomaniac. I bet you that when his name is announced his friends lock up their spoons and send in a hurry call to police headquarters for a squad to come and see that he doesn’t sneak the front door. Of course he meant to steal it! He has a museum of his own down in the country. My Cheops is going to lend tone to that. I’d give five thousand dollars to get it back. If there’s a yegg in this country with the spirit to break into the castle and steal that scarab and hand it back to me, there’s five thousand waiting for him right here; and if he wants to he can knock that old safe blower on the head with a jimmy into the bargain.”

“But, father, why can’t you simply go to him and say it’s yours and that you must have it back?”

“And have him come back at me by calling off this engagement of yours? Not if I know it! You can’t go about the place charging a man with theft and ask him to go on being willing to have his son marry your daughter, can you? The slightest suggestion that I thought he had stolen this scarab and he would do the Proud Old English Aristocrat and end everything. He’s in the strongest position a thief has ever been in. You can’t get at him.”

“I didn’t think of that.”

“You don’t think at all. That’s the trouble with you,” said Mr. Peters.

You see now why we prefer writing motion-picture scenarios. It is painful to a refined and sensitive young novelist to have to set down such a scene between father and child; but what is one to do? Years of indigestion had made Mr. Peters’ temper, even when in a normal mood, perfectly impossible; in a crisis like this it ran amuck. He vented it on Aline because he had always vented his irritabilities on Aline; because the fact of her sweet, gentle disposition, combined with the fact of their relationship, made her the ideal person to receive the overflow of his black moods. While his wife had lived he had bullied her. On her death Aline had stepped into the vacant position.

Aline did not cry, because she was not a girl who was given to tears; but, for all her placid good temper, she was wounded. She was a girl who liked everything in the world to run smoothly and easily, and these scenes with her father always depressed her. She took advantage of a lull in Mr. Peters’ flow of words and slipped from the room.

Her cheerfulness had received a shock. She wanted sympathy. She wanted comforting. For a moment she considered George Emerson in the rôle of comforter; but there were objections to George in this character. Aline was accustomed to tease and chaff George, but at heart she was a little afraid of him; and instinct told her that, as comforter, he would be too volcanic and supermanly for a girl who was engaged to marry another man in June. George, as comforter, would be far too prone to trust to action rather than to the soothing power of the spoken word. George’s idea of healing the wound, she felt, would be to push her into a cab and drive to the nearest registrar’s.

No; she would not go to George. To whom, then? The vision of Joan Valentine came to her—of Joan as she had seen her yesterday, strong, cheerful, self-reliant, bearing herself, in spite of adversity, with a valiant jauntiness. Yes; she would go and see Joan. She put on her hat and stole from the house.

Curiously enough, only a quarter of an hour before, R. Jones had set out with exactly the same object in view.

How pleasant it is, after assisting at a scene of violence and recrimination, to be transferred to one of peace and good will. It is with a sense of relief that I find that the snipelike flight of this story takes us next far from Mr. Peters and his angry outpourings to the cozy smoking room of Blandings Castle.

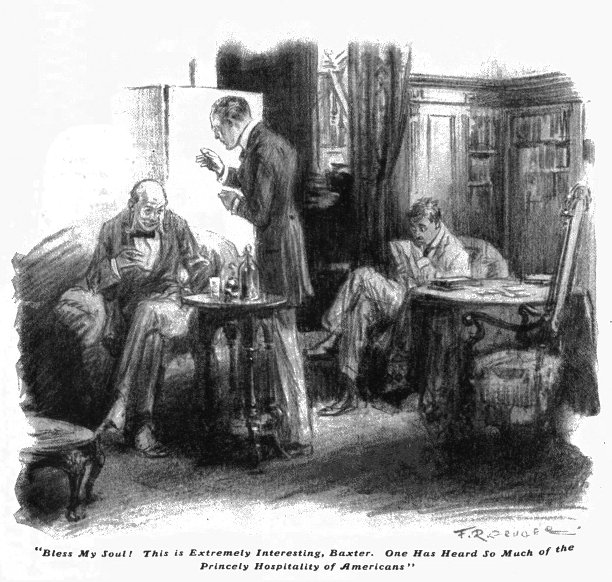

At half-past seven that night three men sat in the cozy smoking room of Blandings Castle.

They were variously occupied. In the long chair nearest the door the Honorable Frederick Threepwood—Freddie to pals—was reading. Next to him sat a young man whose eyes, glittering through rimless spectacles, were concentrated on the upturned faces of several neat rows of playing cards—Rupert Baxter, Lord Emsworth’s invaluable secretary, had no vices, but he sometimes relaxed his busy brain with a game of solitaire. Beyond Baxter, a cigar in his mouth and a weak highball at his side, the Earl of Emsworth took his ease. After the scene we have just been through, it does one good merely to contemplate such a picture.

The book the Honorable Freddie was reading was a small paper-covered book. Its cover was decorated with a color scheme in red, black and yellow, depicting a tense moment in the lives of a man with a black beard, a man with a yellow beard, a man without any beard at all, and a young woman who, at first sight, appeared to be all eyes and hair. The man with the black beard, to gain some private end, had tied this young woman with ropes to a complicated system of machinery, mostly wheels and pulleys. The man with the yellow beard was in the act of pushing or pulling a lever. The beardless man, protruding through a trapdoor in the floor, was pointing a large revolver at the parties of the second part.

Beneath this picture were the words: Hands up, you scoundrels! Above it, in a meandering scroll across the page, was: Gridley Quayle, Investigator. The Adventure of the Secret Six. By Felix Clovelly.

The Honorable Freddie did not so much read as gulp the adventure of the Secret Six. His face was crimson with excitement; his hair was rumpled; his eyes bulged. He was absorbed.

This is peculiarly an age in which each of us may, if we do but search diligently, find the literature suited to his mental powers. Grave and earnest men, at Eton and elsewhere, had tried Freddie Threepwood with Greek, with Latin, and with English; and the sheeplike stolidity with which he declined to be interested in the masterpieces of all three tongues had left them with the conviction that he would never read anything.

And then, years afterward, he had suddenly blossomed out as a student—only, it is true, a student of the Adventures of Gridley Quayle; but still a student. His was a dull life and Gridley Quayle was the only person who brought romance into it. Existence for the Honorable Freddie was simply a sort of desert, punctuated with monthly oases in the shape of new Quayle adventures. It was his ambition to meet the man who wrote them.

Lord Emsworth sat and smoked, and sipped and smoked again, at peace with all the world. His mind was as nearly a blank as it is possible for the human mind to be. The hand that had not the task of holding the cigar was at rest in his trousers pocket. The fingers of it fumbled idly with a small, hard object.

Gradually it filtered into his lordship’s mind that this small, hard object was not familiar. It was something new—something that was neither his keys nor his pencil; nor was it his small change. He yielded to a growing curiosity and drew it out. He examined it. It was a little something, rather like a fossilized beetle. It touched no chord in him. He looked at it with amiable distaste.

“Now how in the world did that get there?” he said.

The Honorable Freddie paid no attention to the remark. He was now at the very crest of his story, when every line intensified the thrill. Incident was succeeding incident. The Secret Six were here, there and everywhere, like so many malignant June bugs. Annabel, the heroine, was having a perfectly rotten time—kidnapped and imprisoned every few minutes. Gridley Quayle, hot on the scent, was covering somebody or other with his revolver almost continuously. Lord Threepwood had no time for chatting with his father.

Not so Rupert Baxter. Chatting with Lord Emsworth was one of the things for which he received his salary. He looked up from his cards.

“Lord Emsworth?”

“I have found a curious object in my pocket, Baxter. I was wondering how it got there.”

He handed the thing to his secretary. Rupert Baxter’s eyes lit up with sudden enthusiasm. He gasped.

“Magnificent!” he cried. “Superb!”

Lord Emsworth looked at him inquiringly.

“It is a scarab, Lord Emsworth; and unless I am mistaken—and I think I may claim to be something of an expert—a Cheops of the Fourth Dynasty. A wonderful addition to your museum!”

“Is it? By Gad! You don’t say so, Baxter!”

“It is, indeed. If it is not a rude question, how much did you give for it, Lord Emsworth? It must have been the gem of somebody’s collection. Was there a sale at Christie’s this afternoon?”

Lord Emsworth shook his head.

“I did not get it at Christie’s, for I recollect that I had an important engagement which prevented my going to Christie’s. I had—to be sure; yes—I had promised to call on Mr. Peters and examine his collection of—— Now I wonder what it was that Mr. Peters said he collected!”

“Mr. Peters is one of the best-known living collectors of scarabs.”

“Scarabs! You are quite right, Baxter. Now that I recall the episode, this is a scarab; and Mr. Peters gave it to me.”

“Gave it to you, Lord Emsworth?”

“Yes. The whole scene comes back to me. Mr. Peters, after telling me a great many exceedingly interesting things about scarabs, which I regret to say I cannot remember, gave me this. And you say it is really valuable, Baxter?”

“It is, from a collector’s point of view, of extraordinary value.”

“Bless my soul!” Lord Emsworth beamed. “This is extremely interesting, Baxter. One has heard so much of the princely hospitality of Americans. How exceedingly kind of Mr. Peters! I shall certainly treasure it, though I must confess that from a purely spectacular standpoint it leaves me a little cold. However, I must not look a gift horse in the mouth—eh, Baxter?”

From afar came the silver booming of a gong. Lord Emsworth rose.

From afar came the silver booming of a gong. Lord Emsworth rose.

“Time to dress for dinner? I had no idea it was so late. Baxter, you will be going past the museum door. Will you be a good fellow and place this among the exhibits? You will know what to do with it better than I. I always think of you as the curator of my little collection, Baxter—ha-ha! Mind how you step when you are in the museum. I was painting a chair there yesterday and I think I left the paint pot on the floor.”

He cast a less amiable glance at his studious son.

“Get up, Frederick, and go and dress for dinner. What is that trash you are reading?”

The Honorable Freddie came out of his book much as a sleepwalker wakes—with a sense of having been violently assaulted. He looked up with a kind of stunned plaintiveness.

“Eh, governor?”

“Make haste! Beach rang the gong five minutes ago. What is that you are reading?”

“Oh, nothing, governor—just a book.”

“I wonder you can waste your time on such trash. Make haste!”

He turned to the door, and the benevolent expression once more wandered across his face.

“Extremely kind of Mr. Peters!” he said. “Really, there is something almost oriental in the lavish generosity of our American cousins.”

It had taken R. Jones just six hours to discover Joan Valentine’s address. That it had not taken him longer is a proof of his energy and of the excellence of his system of obtaining information; but R. Jones, when he considered it worth his while, could be extremely energetic, and he was a past master at the art of finding out things.

He poured himself out of his cab and rang the bell of Number Seven.

A disheveled maid answered the ring.

“Miss Valentine in?”

“Yes, sir.”

R. Jones produced his card.

“On important business, tell her. Half a minute—I’ll write it.”

He wrote the words on the card and devoted the brief period of waiting to a careful scrutiny of his surroundings. He looked out into the court and he looked as far as he could down the dingy passage; and the conclusions he drew from what he saw were complimentary to Miss Valentine.

“If this girl is the sort of girl who would hold up Freddie’s letters,” he mused, “she wouldn’t be living in a place like this. If she were on the make she would have more money than she evidently possesses. Therefore, she is not on the make; and I am prepared to bet that she destroyed the letters as fast as she got them.” Those were, roughly, the thoughts of R. Jones as he stood in the doorway of Number Seven; and they were important thoughts inasmuch as they determined his attitude toward Joan in the approaching interview. He perceived that this matter must be handled delicately—that he must be very much the gentleman. It would be a strain, but he must do it.

The maid returned and directed him to Joan’s room with a brief word and a sweeping gesture.

“Eh?” said R. Jones. “First floor, did you say?”

“Front,” said the maid.

R. Jones trudged laboriously up the short flight of stairs. It was very dark on the stairs and he stumbled. Eventually, however, light came to him through an open door. Looking in, he saw a girl standing at the table. She had an air of expectation; so he deduced that he had reached his journey’s end.

“Miss Valentine?”

“Please come in.”

R. Jones waddled in.

“Not much light on your stairs.”

“No. Will you take a seat?”

“Thanks.”

One glance at the girl convinced R. Jones that he had been right. Circumstances had made him a rapid judge of character, for in the profession of living by one’s wits in a large city the first principle of offense and defense is to sum people up at first sight. This girl was not on the make.

Joan Valentine was a tall girl with wheat-gold hair and eyes as brightly blue as a November sky when the sun is shining on a frosty world. There was in them a little of November’s cold glitter, too, for Joan had been through much in the last few years; and experience, even when it does not harden, erects a defensive barrier between its children and the world.

Her eyes were eyes that looked straight and challenged. They could thaw to the satin blue of the Mediterranean Sea, where it purrs about the little villages of Southern France; but they did not thaw for everybody. She looked what she was—a girl of action; a girl whom life had made both reckless and wary—wary of friendly advances, reckless when there was a venture afoot.

Her eyes, as they met R. Jones’ now, were cold and challenging. She, too, had learned the trick of swift diagnosis of character, and what she saw of R. Jones in that first glance did not impress her favorably.

“You wished to see me on business?”

“Yes,” said R. Jones. “Yes. . . . Miss Valentine, may I begin by begging you to realize that I have no intention of insulting you?”

Joan’s eyebrows rose. For an instant she did her visitor the injustice of suspecting that he had been dining too well.

“I don’t understand.”

“Let me explain: I have come here,” R. Jones went on, getting more gentlemanly every moment, “on a very distasteful errand, to oblige a friend. Will you bear in mind that whatever I say is said entirely on his behalf?”

By this time Joan had abandoned the idea that this stout person was a life-insurance tout, and was inclining to the view that he was collecting funds for a charity.

“I came here at the request of the Honorable Frederick Threepwood.”

“I don’t quite understand.”

“You never met him, Miss Valentine; but when you were in the chorus at the Piccadilly Theatre, I believe he wrote you some very foolish letters. Possibly you have forgotten them?”

“I certainly have.”

“You have probably destroyed them—eh?”

“Certainly. I don’t often keep letters. Why do you ask?”

“Well, you see, Miss Valentine, the Honorable Frederick Threepwood is about to be married; and he thought that possibly, on the whole, it would be better that the letters—and poetry—that he wrote you, were nonexistent.”

Not all R. Jones’ gentlemanliness—and during this speech he diffused it like a powerful scent in waves about him—could hide the unpleasant meaning of the words.

“He was afraid I might try to blackmail him?” said Joan, with formidable calm.

R. Jones raised and waved a fat hand deprecatingly.

“My dear Miss Valentine!”

Joan rose and R. Jones followed her example. The interview was plainly at an end.

“Please tell Mr. Threepwood to make his mind quite easy. He is in no danger.”

“Exactly—exactly; precisely! I assured Threepwood that my visit here would be a mere formality. I was quite sure you had no intention whatever of worrying him. I may tell him definitely, then, that you have destroyed the letters?”

“Yes. Good evening.”

“Good evening, Miss Valentine.”

The closing of the door behind him left him in total darkness, but he hardly liked to return and ask Joan to reopen it in order to light him on his way. He was glad to be out of her presence. He was used to being looked at in an unfriendly way by his fellows, but there had been something in Joan’s eyes that had curiously discomfited him.

R. Jones groped his way down, relieved that all was over and had ended well. He believed what she had told him, and he could conscientiously assure Freddie that the prospect of his sharing the fate of poor old Percy was nonexistent. It is true that he proposed to add in his report that the destruction of the letters had been purchased with difficulty, at a cost of just five hundred pounds; but that was a mere business formality.

He had almost reached the last step when there was a ring at the front door. With what he was afterward wont to call an inspiration, he retreated with unusual nimbleness until he had almost reached Joan’s door again. Then he leaned over the baluster and listened.

The disheveled maid opened the door. A girl’s voice spoke:

“Is Miss Valentine in?”

“She’s in; but she’s engaged.”

“I wish you would go up and tell her that I want to see her. Say it’s Miss Peters—Miss Aline Peters.”

The baluster shook beneath R. Jones’ sudden clutch. For a moment he felt almost faint. Then he began to think swiftly. A great light had dawned on him, and the thought outstanding in his mind was that never again would he trust a man or woman on the evidence of his senses. He could have sworn that this Valentine girl was on the level. He had been perfectly satisfied with her statement that she had destroyed the letters. And all the while she had been playing as deep a game as he had come across in the whole course of his professional career! He almost admired her. How she had taken him in!

It was obvious now what her game was. Previous to his visit she had arranged a meeting with Freddie’s fiancée, with the view of opening negotiations for the sale of the letters. She had held him, Jones, at arm’s length because she was going to sell the letters to whoever would pay the best price. But for the accident of his happening to be here when Miss Peters arrived, Freddie and his fiancée would have been bidding against each other and raising each other’s price.

R. Jones had worked the same game himself a dozen times, and he resented the entry of female competition into what he regarded as essentially a male field of enterprise.

As the maid stumped up the stairs he continued his retreat. He heard Joan’s door open, and the stream of light showed him the disheveled maid standing in the doorway.

“Ow, I thought there was a gentleman with you, miss.”

“He left a moment ago. Why?”

“There’s a lady wants to see you. Miss Peters, her name is.”

“Will you ask her to come up?”

The disheveled maid was no polished mistress of ceremonies. She leaned down into the void and hailed Aline.

“She says will you come up?”

Aline’s feet became audible on the staircase. There were greetings.

“Whatever brings you here, Aline?”

“Am I interrupting you, Joan, dear?”

“No. Do come in! I was only surprised to see you so late. I didn’t know you paid calls at this hour. Is anything wrong? Come in.”

The door closed, the maid retired to the depths, and R. Jones stole cautiously down again. He was feeling absolutely bewildered. Apparently his deductions, his second thoughts, had been all wrong, and Joan was, after all, the honest person he had imagined at first sight. Those two girls had talked to each other as though they were old friends; as though they had known each other all their lives. That was the thing which perplexed R. Jones.

With the tread of a Red Indian, he approached the door and put his ear to it. He found he could hear quite comfortably.

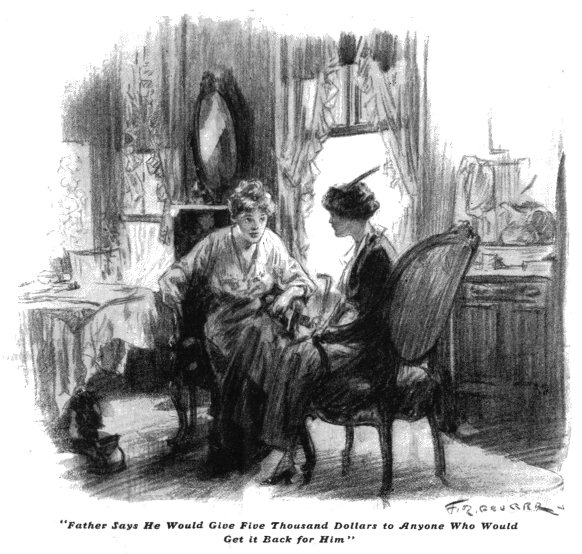

Aline, meantime, inside the room, had begun to draw comfort from Joan’s very appearance—she looked so capable.

Joan’s eyes had changed the expression they had contained during the recent interview. They were soft now, with a softness that was half compassionate, half contemptuous. It is the compensation which life gives to those whom it has handled roughly in order that they shall be able to regard with a certain contempt the small troubles of the sheltered. Joan remembered Aline of old, and knew her for a perennial victim of small troubles. Even in their schooldays she had always needed to be looked after and comforted. Her sweet temper had seemed to invite the minor slings and arrows of fortune. Aline was a girl who inspired protectiveness in a certain type of her fellow human beings. It was this quality in her that kept George Emerson awake at nights; and it appealed to Joan now.

Joan, for whom life was a constant struggle to keep the wolf within a reasonable distance from the door, and who counted that day happy on which she saw her way clear to paying her weekly rent and possibly having a trifle over for some coveted hat or pair of shoes, could not help feeling, as she looked at Aline, that her own troubles were as nothing, and that the immediate need of the moment was to pet and comfort her friend. Her knowledge of Aline told her the probable tragedy was that she had lost a brooch or had been spoken to crossly by somebody; but it also told her that such tragedies bulked very large on Aline’s horizon.

Trouble, after all, like beauty, is in the eye of the beholder; and Aline was far less able to endure with fortitude the loss of a brooch than she herself to bear the loss of a position the emoluments of which meant the difference between having just enough to eat and starving.

“You’re worried about something,” she said. “Sit down and tell me all about it.”

Aline sat down and looked about her at the shabby room. By that curious process of the human mind which makes the spectacle of another’s misfortune a palliative for one’s own, she was feeling oddly comforted already. Her thoughts were not definite and she could not analyze them; but what they amounted to was that, though it was an unpleasant thing to be bullied by a dyspeptic father, the world manifestly held worse tribulations, which her father’s other outstanding quality, besides dyspepsia—wealth, to wit—enabled her to avoid.

It was at this point that the dim beginnings of philosophy began to invade her mind. The thing resolved itself almost into an equation. If father had not had indigestion he would not have bullied her. But, if father had not made a fortune he would not have had indigestion. Therefore, if father had not made a fortune he would not have bullied her. Practically, in fact, if father did not bully her he would not be rich. And if he were not rich——

She took in the faded carpet, the stained wall paper and the soiled curtains with a comprehensive glance. It certainly cut both ways. She began to be a little ashamed of her misery.

“It’s nothing at all, really,” she said. “I think I’ve been making rather a fuss about very little.”

Joan was relieved. The struggling life breeds moods of depression, and such a mood had come to her just before Aline’s arrival. Life, at that moment, had seemed to stretch before her like a dusty, weary road, without hope. She was sick of fighting. She wanted money and ease, and a surcease from this perpetual race with the weekly bills. The mood had been the outcome, though she did not realize it, of her yesterday’s meeting with Aline.

Mr. Peters might be unguarded in his speech when conversing with his daughter—he might play the tyrant toward her in many ways; but he did not stint her in the matter of dress allowance, and, on the occasion when she met Joan, Aline had been wearing so Parisian a hat and a tailor-made suit of such obviously expensive simplicity that green-eyed envy had almost spoiled Joan’s pleasure at meeting this friend of her opulent days.

She had suppressed the envy, and it had revenged itself by assaulting her afresh in the form of the worst fit of the blues she had had in two years. She had been loyally ready to sink her depression in order to alleviate Aline’s, but it was a distinct relief to find that the feat would not be necessary.

“Never mind,” she said. “Tell me what the very little thing was.”

“It was only father,” said Aline simply.

Joan cast her mind back to the days of school and placed father as a rather irritable person, vaguely reputed to be something of an ogre in his home circle.

“Was he angry with you about something?” she asked.

“Not exactly angry with me; but—well, I was there.”

Joan’s depression lifted slightly. She had forgotten, in the stunning anguish of the sudden spectacle of that hat and that tailor-made suit, that Paris hats and hundred-and-twenty-dollar suits not infrequently had what the vulgar term a string attached to them. After all, she was independent. She might have to murder her beauty with frocks that had never been nearer Paris than the Tottenham Court Road; but at least no one bullied her because she happened to be at hand when tempers were short.

“What a shame!” she said. “Tell me all about it.”

With a prefatory remark that it was all so ridiculous, really, Aline narrated the afternoon’s events.

Joan heard her out, checking a strong disposition to giggle. Her viewpoint was that of the average person, and the average person cannot see the importance of the scarab in the scheme of things. The opinion she formed of Mr. Peters was of his being an eccentric old gentleman making a great to-do about nothing at all. Losses had to have a concrete value before they could impress Joan. It was beyond her to grasp that Mr. Peters would sooner have lost a diamond necklace, if he had happened to possess one, than his Cheops of the Fourth Dynasty.

It was not until Aline, having concluded her tale, added one more strand to it that she found herself treating the matter seriously.

“Father says he would give five thousand dollars to anyone who would get it back for him.”

“What!”

“What!”

The whole story took on a different complexion for Joan. Money talks. Mr. Peters’ words might have been merely the rhetorical outburst of a heated moment; but, even discounting them, there seemed to remain a certain exciting substratum. A man who shouts that he will give five thousand dollars for a thing may very well mean he will give five hundred, and Joan’s finances were perpetually in a condition which makes five hundred dollars a sum to be gasped at.

“He wasn’t serious, surely!”

“I think he was,” said Aline.

“But five thousand dollars!”

“It isn’t really very much to father, you know. He gave away a hundred thousand a year ago to a university.”

“But for a grubby little scarab!”

“You don’t understand how father loves his scarabs. Since he retired from business he has been simply wrapped up in them. You know collectors are like that. You read in the papers about men giving all sorts of money for funny things.”

Outside the door R. Jones, his ear close to the panel, drank in all these things greedily. He would have been willing to remain in that attitude indefinitely in return for this kind of special information; but just as Aline said these words a door opened on the floor above, and somebody came out, whistling, and began to descend the stairs.

R. Jones stood not on the order of his going. He was down in the hall and fumbling with the handle of the front door with an agility of which few casual observers of his dimensions would have deemed him capable. The next moment he was out in the street, walking calmly toward Leicester Square, pondering over what he had heard.

Much of R. Jones’ substantial annual income was derived from pondering over what he had heard.

In the room Joan was looking at Aline with the distended eyes of one who sees visions or has inspirations. She got up. There are occasions when one must speak standing.

“Then you mean to say that your father would really give five thousand dollars to anyone who got this thing back for him?”

“I am sure he would. But who could do it?”

“I could,” said Joan. “And what is more, I’m going to!”

Aline stared at her helplessly. In their schooldays, Joan had always swept her off her feet. Then, she had always had the feeling that with Joan nothing was impossible. Heroine worship, like hero worship, dies hard. She looked at Joan now with the stricken sensation of one who has inadvertently set powerful machinery in motion.

“But, Joan!” It was all she could say.

“My dear child, it’s perfectly simple. This earl of yours has taken the thing off to his castle, like a brigand. You say you are going down there on Friday for a visit. All you have to do is to take me along with you, and sit back and watch me get busy with the scarab.”

“But, Joan!”

“Where’s the difficulty?”

“I don’t see how I could take you down very well.”

“Why not?”

“Oh, I don’t know.”

“But what is your objection?”

“Well—don’t you see?—if you went down there as a friend of mine and were caught stealing the scarab, there would be just the trouble father wants to avoid—about my engagement, you see, and so on.”

It was an aspect of the matter that had escaped Joan. She frowned thoughtfully.

“I see. Yes, there is that; but there must be a way.”

“You mustn’t, Joan—really! Don’t think any more about it.”

“Not think any more about it! My child, do you even faintly realize what five thousand dollars—or a quarter of five thousand dollars—means to me? I would do anything for it—anything! And there’s the fun of it. I don’t suppose you can realize that, either. I want a change. I want something new. I’ve been grubbing away here on nothing a week for years, and it’s time I had a vacation. There must be a way by which you could get me down—— Why, of course! Why didn’t I think of it before! You shall take me on Friday as your lady’s maid!”

“But, Joan, I couldn’t!”

“Why not?”

“I—I couldn’t.”

“Why not?”

“Oh, well!”

Joan advanced on her where she sat and grasped her firmly by the shoulders. Her face was inflexible.

“Aline, my pet, it’s no good arguing. You might just as well argue with a wolf on the trail of a fat Russian peasant. I need that money. I need it in my business. I need it worse than anybody has ever needed anything. And I’m going to have it! From now on, until further notice, I am your lady’s maid. You can give your present one a holiday.”

Aline met her eyes waveringly. The spirit of the old schooldays, when nothing was impossible where Joan was concerned, had her in its grip. Moreover, the excitement of the scheme began to attract her.

“But, Joan,” she said, “you know it’s simply ridiculous. You could never pass as a lady’s maid. The other servants would find you out. I expect there are all sorts of things a lady’s maid has got to do and not do.”

“My dear Aline, I know them all. You can’t stump me on below-stairs etiquette. I have been a lady’s maid!”

“Joan!”

“It’s quite true—three years ago, when I was more than usually impecunious. The wolf was glued to the door like a postage stamp; so I answered an advertisement and became a lady’s maid.”

“You seem to have done everything.”

“I have—pretty nearly. It’s all right for you idle rich, Aline—you can sit still and contemplate life; but we poor working girls have got to hustle.”

Aline laughed.

“You know you always could make me do anything you wanted in the old days, Joan. I suppose I have got to look on this as quite settled now?”

“Absolutely settled! Oh, Aline, there’s one thing you must remember: Don’t call me Joan when I’m down at the castle. You must call me Valentine.” She paused. The recollection of the Honorable Freddie had come to her. No; Valentine would not do! “No; not Valentine,” she went on—“it’s too jaunty. I used it three years ago, but it never sounded just right. I want something more respectable, more suited to my position. Can’t you suggest something?”

Aline pondered.

“Simpson?”

“Simpson! It’s exactly right. You must practice it. Simpson! Say it kindly and yet distantly, as though I were a worm, but a worm for which you felt a mild liking. Roll it round your tongue.”

“Simpson.”

“Splendid! Now once again—a little more haughtily.”

“Simpson—Simpson—Simpson.”

Joan regarded her with affectionate approval.

“It’s wonderful!” she said. “You might have been doing it all your life.”

“What are you laughing at?” asked Aline.

“Nothing,” said Joan. “I was just thinking of something. There’s a young man who lives on the floor above this, and I was lecturing him yesterday on enterprise. I told him to go and find something exciting to do. I wonder what he would say if he knew how thoroughly I am going to practice what I preach!”

IV

ON THE morning following Aline’s visit to Joan Valentine, Ashe sat in his room, the Morning Post on the table before him. The heady influence of Joan had not yet ceased to work within him; and he proposed, in pursuance of his promise to her, to go carefully through the columns of advertisements, however pessimistic he might feel concerning the utility of that action.

His first glance assured him that the vast fortunes of the philanthropists whose acquaintance he had already made in print were not yet exhausted. Brian MacNeill still dangled his gold before the public; so did Angus Bruce; so did Duncan Macfarlane; so, likewise, did Wallace Mackintosh and Donald McNab. They still had the money and they still wanted to give it away.

Ashe was reading listlessly down the column when, from the mass of advertisements, one of an unusual sort detached itself.

Wanted: Young Man of good appearance, who is poor and reckless, to undertake a delicate and dangerous enterprise. Good pay for the right man. Apply between the hours of ten and twelve at offices of Mainprice, Mainprice & Boole, 3, Denvers Street, Strand.

And as he read it, half past ten struck on the little clock on his mantelpiece. It was probably this fact that decided Ashe. If he had been compelled to postpone his visit to the offices of Messrs. Mainprice, Mainprice & Boole until the afternoon it is possible that barriers of laziness might have reared themselves in the path of adventure; for Ashe, an adventurer at heart, was also uncommonly lazy. As it was, however, he could make an immediate start.

Pausing but to put on his shoes, and having satisfied himself by a glance in the mirror that his appearance was reasonably good, he seized his hat, shot out of the narrow mouth of Arundel Street like a shell, and scrambled into a taxicab, with the feeling that—short of murder—they could not make it too delicate and dangerous for him.

He was conscious of strange thrills. This, he told himself, was the only possible mode of life with spring in the air. He had always been partial to those historical novels in which the characters are perpetually vaulting on chargers and riding across country on perilous errands. This leaping into taxicabs to answer stimulating advertisements in the Morning Post was very much the same sort of thing. It was with fine fervor animating him that he entered the gloomy offices of Mainprice, Mainprice & Boole. His brain was afire and he felt ready for anything.

“I have come in ans——” he began, to the diminutive office boy, who seemed to be the nearest thing visible to a Mainprice or a Boole.

“Siddown. Gottatakeyerturn,” said the office boy; and for the first time Ashe perceived that the anteroom in which he stood was crowded to overflowing.

This, in the circumstances, was something of a damper. He had pictured himself, during his ride in the cab, striding into the office and saying: “The delicate and dangerous enterprise. Lead me to it!” He had not realized until now that he was not the only man in London who read the advertisement columns of the Morning Post, and for an instant his heart sank at the sight of all this competition. A second and more comprehensive glance at his rivals gave him confidence.

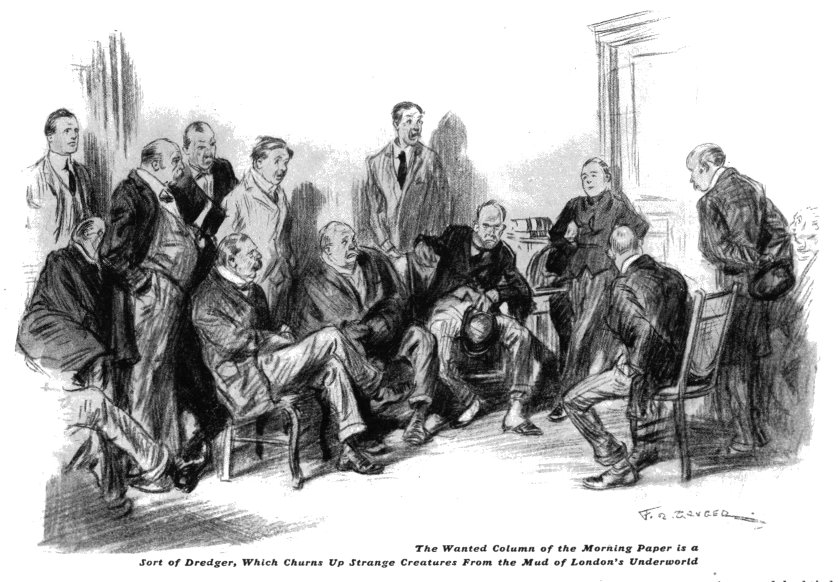

The Wanted column of the morning paper is a sort of dredger, which churns up strange creatures from the mud of London’s underworld. Only in response to the dredger’s operations do they come to the surface in such numbers as to be noticeable, for as a rule they are of a solitary habit and shun company; but when they do come they bring with them something of the horror of the depths.

It is the saddest spectacle in the world—that of the crowd collected by a Wanted advertisement. They are so palpably not wanted by anyone for any purpose whatsoever; yet every time they gather together with a sort of hopeful hopelessness. What they were originally—the units of these collections—Heaven knows! Fate has battered out of them every trace of individuality. Each now is exactly like his neighbor—no worse; no better.

Ashe, as he sat and watched them, was filled with conflicting emotions. One half of him, thrilled with the glamour of adventure, was chafing at the delay, and resentful of these poor creatures as of so many obstacles to the beginning of all the brisk and exciting things that lay behind the mysterious brevity of the advertisement; the other, pitifully alive to the tragedy of the occasion, was grateful for the delay.

On the whole, he was glad to feel that if one of these derelicts did not secure the “good pay for the right man,” it would not be his fault. He had been the last to arrive, and he would be the last to pass through that door, which was the gateway of adventure—the door with Mr. Boole inscribed on its ground glass, behind which sat the author of the mysterious request for assistance, interviewing applicants. It would be through their own shortcomings—not because of his superior attractions—if they failed to please that unseen arbiter.

That they were so failing was plain. Scarcely had one scarred victim of London’s unkindness passed through before the bell would ring; the office boy, who, in the intervals of frowning sternly on the throng, as much as to say that he would stand no nonsense, would cry, “Next!” and another dull-eyed wreck would drift through, to be followed a moment later by yet another. The one fact at present ascertainable concerning the unknown searcher for reckless young men of good appearance was that he appeared to be possessed of considerable decision of character, a man who did not take long to make up his mind. He was rejecting applicants now at the rate of two a minute.

Expeditious though he was, he kept Ashe waiting for a considerable time. It was not until the hands of the fat clock over the door pointed to twenty minutes past eleven that the office boy’s Next! found him the only survivor. He gave his clothes a hasty smack with the palm of his hand and his hair a fleeting dab to accentuate his good appearance, and turned the handle of the door of fate.

The room assigned by the firm to their Mr. Boole for his personal use was a small and dingy compartment, redolent of that atmosphere of desolation which lawyers alone know how to achieve. It gave the impression of not having been swept since the foundation of the firm in the year 1786. There was one small window, covered with grime. It was one of those windows you see only in lawyers’ offices. Possibly some reckless Mainprice or harebrained Boole had opened it in a fit of mad excitement induced by the news of the Battle of Waterloo, in 1815, and had been instantly expelled from the firm. Since then no one had dared to tamper with it.

Looking through this window—or, rather, looking at it, for X rays could hardly have succeeded in actually penetrating the alluvial deposits on the glass—was a little man. As Ashe entered, he turned and looked at him as though he hurt him rather badly in some tender spot.

Ashe was obliged to own to himself that he felt a little nervous. It is not every day that a young man of good appearance, who has led a quiet life, meets face to face one who is prepared to pay him well for doing something delicate and dangerous. To Ashe the sensation was entirely novel. The most delicate and dangerous act he had performed to date had been the daily mastication of Mrs. Bell’s breakfast. Yes, he had to admit it—he was nervous; and the fact that he was nervous made him hot and uncomfortable.

To judge him by his appearance the man at the window was also hot and uncomfortable. He was a little, truculent-looking man, and his face at present was red with a flush that sat unnaturally on a normally lead-colored face. His eyes looked out from under thick gray eyebrows with an almost tortured expression. This was partly owing to the strain of interviewing Ashe’s preposterous predecessors, but principally to the fact that the little man had suddenly been seized with acute indigestion, a malady to which he was peculiarly subject.

He removed from his mouth the black cigar he was smoking, inserted a digestive tabloid, and replaced the cigar. Then he concentrated his attention on Ashe. As he did so the hostile expression of his face became modified. He looked surprised and—grudgingly—pleased.

“Well, what do you want?” he said.

“I came in answer to——”

“In answer to my advertisement? I had given up hope of seeing anything part human. I thought you must be one of the clerks. You’re certainly more like what I advertised for. Of all the seedy bunches of dead beats I ever struck, the aggregation I’ve just been interviewing was the seediest! When I spend good money in advertising for a young man of good appearance, I want a young man of good appearance—not a tramp of fifty-five.”

Ashe was sorry for his predecessors, but he was bound to admit that they certainly had corresponded somewhat faithfully to the description just given. The comparative cordiality of his own reception removed the slight nervousness that had been troubling him. He began to feel confident—almost jaunty.

“I’m through,” said the little man wearily. “I’ve had enough of interviewing applicants. You’re the last one I’ll see. Are there any more hobos outside?”

“Not when I came in.”

“Then we’ll get down to business. I’ll tell you what I want done, and if you are willing you can do it; if you are not willing you can leave it—and go to the devil! Sit down.”

Ashe sat down. He resented the little man’s tone, but this was not the moment for saying so. His companion scrutinized him narrowly.

“So far as appearance goes,” he said, “you are what I want.” Ashe felt inclined to bow. “Whoever takes on this job has got to act as my valet, and you look like a valet.” Ashe felt less inclined to bow. “You’re tall and thin and ordinary-looking. Yes; so far as appearance goes, you fill the bill.”

It seemed to Ashe that it was time to correct an impression the little man appeared to have formed.

“I am afraid,” he said, “if all you want is a valet, you will have to look elsewhere. I got the idea from your advertisement that something rather more exciting was in the air. I can recommend you to several good employment agencies if you wish.” He rose. “Good morning!” he said.

He would have liked to fling the massive pewter inkwell at this little creature who had so keenly disappointed him.

“Sit down!” snapped the other.

Ashe resumed his seat. The hope of adventure dies hard on a spring morning when one is twenty-six, and he had the feeling that there was more to come.

“Don’t be a damned fool!” said the little man. “Of course I’m not asking you to be a valet and nothing else.”

“You would want me to do some cooking and plain sewing on the side, perhaps?”

Their eyes met in a hostile glare. The flush on the little man’s face deepened.

“Are you trying to get fresh with me?” he demanded dangerously.

“Yes,” said Ashe.

The answer seemed to disconcert his adversary. He was silent for a moment.

“Well,” he said at last, “maybe it’s all for the best. If you weren’t full of gall probably you wouldn’t have come here at all; and whoever takes on this job of mine has got to have gall if he has nothing else. I think we shall suit each other.”

“What is the job?”

The little man’s face showed doubt and perplexity.

“It’s awkward. If I’m to make the thing clear to you I’ve got to trust you. And I don’t know a thing about you. I wish I had thought of that before I inserted the advertisement.”

Ashe appreciated the difficulty.

“Couldn’t you make an A-B case out of it?”

“Maybe I could if I knew what an A-B case was.”

“Call the people mixed up in it A and B.”

“And forget, halfway through, who was which! No; I guess I’ll have to trust you.”

“I’ll play square.”

The little man fastened his eyes on Ashe’s in a piercing stare. Ashe met them smilingly. His spirits, always fairly cheerful, had risen dangerously high by now. There was something about the little man, in spite of his brusqueness and ill temper, which made him feel flippant.

“Pure white!” said Ashe.

“Eh?”

“My soul! And this”—he thumped the left section of his waistcoat—“solid gold. ‘You may fire when ready, Gridley.’ Proceed, professor.”

“I don’t know where to begin.”

“Without presuming to dictate, why not at the beginning?”

“It’s all so darned complicated that I don’t rightly know which is the beginning. Well, see here: I collect scarabs. I’m crazy about scarabs. Ever since I quit business, you might say that I have practically lived for scarabs.”

“Though it sounds like an unkind thing to say of anyone,” said Ashe. “Incidentally, what are scarabs?” He held up his hand. “Wait! It all comes back to me. Expensive classical education, now bearing belated fruit. Scarabæus—Latin; noun, nominative—a beetle. Scarabæum—accusative—the beetle. Scarabæi—of the beetle. Scarabæo—to or for the beetle. I remember now. Egypt—Rameses—Pyramids—sacred scarabs! Right!”

“Well, I guess I’ve got together the best collection of scarabs outside the British Museum, and some of them are worth what you like to me. I don’t reckon money when it comes to a question of my scarabs. Do you understand?”

“Sure, Mike!”

Displeasure clouded the little man’s face.

“My name is not Mike.”

“I used the word figuratively, as it were.”

“Well, don’t do it again. My name is J. Preston Peters, and Mr. Peters will do as well as anything else when you want to attract my attention.”

“Mine is Marson. You were saying, Mr. Peters?”

“Well, it’s this way,” said the little man.

Shakspere and Pope have both emphasized the tediousness of a twice-told tale; so the Episode of the Stolen Scarab need not be repeated at this point, though it must be admitted that Mr. Peters’ version of it differed considerably from the calm, dispassionate description the author, in his capacity of official historian, has given earlier in the story.

In Mr. Peters’ version the Earl of Emsworth appeared as a smooth and purposeful robber, a sort of elderly Raffles, worming his way into the homes of the innocent, and sparing only that portion of their property which was too heavy for him to carry away. Mr. Peters, indeed, specifically described the Earl of Emsworth as an oily old second-story man.

It took Ashe some little time to get a thorough grasp of the tangled situation; but he did it at last. Only one point perplexed him.

“You want to hire somebody to go to the castle and get this scarab back for you. I follow that. But why go as your valet?”

“That’s simple enough. You don’t think I’m asking him to buy a black mask and break in, do you? I’m making it as easy for him as possible. I can’t take a secretary down to the castle, for everybody knows that, now I’ve retired, I haven’t got a secretary; and if I engaged a new one and he was caught trying to steal my scarab from the earl’s collection it would look suspicious. But a valet is different. Anyone can get fooled by a crook valet with bogus references.”

“I see. There’s just one other point: Suppose your accomplice does get caught—what then?”

“That,” said Mr. Peters, “is the catch; and it’s just because of that I am offering good pay to my man. We’ll suppose, for the sake of argument, that you accept the contract and get caught. Well, if that happens you’ve got to look after yourself. I couldn’t say a word. If I did it would all come out, and so far as the breaking off of my daughter’s engagement to young Threepwood is concerned it would be just as bad as though I had tried to get the thing back myself.

“You’ve got to bear that in mind. You’ve got to remember it if you forget everything else. I don’t appear in this business in any way whatsoever. If you get caught you take what’s coming to you without a word. You don’t turn round and say: ‘I am innocent. Mr. Peters will explain all’—because Mr. Peters certainly won’t. Mr. Peters won’t utter a syllable of protest if they want to hang you.

“No; if you go into this, young man, you go into it with your eyes open. You go into it with a full understanding of the risks—because you think the reward, if you are successful, makes the taking of those risks worth while. You and I know that what you are doing isn’t really stealing; it’s simply a tactful way of getting back my own property. But the judge and jury will have different views.”

“I am beginning to understand,” said Ashe thoughtfully, “why you called the job delicate and dangerous.”

Certainly it had been no overstatement. As a writer of detective stories for the British office boy he had imagined in his time many undertakings that might be so described, but few to which the description was more admirably suited.

“It is,” said Mr. Peters; “and that is why I’m offering good pay. Whoever carries this job through gets five thousand dollars in cash.”

Ashe started.

“Five thousand dollars!”

“Five thousand.”

“When do I begin?”

“You’ll do it?”

“For five thousand I certainly will.”

“With your eyes open?”

“Wide open!”

A look of positive geniality illuminated Mr. Peters’ pinched features. He even went so far as to pat Ashe on the shoulder.

“Good boy!” he said. “Meet me at Paddington Station at four o’clock on Friday. And if there’s anything more you want to know come round to this address.”

There remained the telling of Joan Valentine; for it was obviously impossible not to tell her. When you have revolutionized your life at the bidding of another you cannot well conceal the fact, as though nothing had happened. Ashe had not the slightest desire to conceal the fact. On the contrary, he was glad to have such a capital excuse for renewing the acquaintance.

He could not tell her, of course, the secret details of the thing. Naturally those must remain hidden. No; he would just go airily in and say:

“You know what you told me about doing something new? Well, I’ve just got a job as a valet.”

So he went airily in and said it.

“To whom?” said Joan.

“To a man named Peters—an American.”

Women are trained from infancy up to conceal their feelings. Joan did not start or otherwise express emotion.

“Not Mr. J. Preston Peters?”

“Yes. Do you know him? What a remarkable thing!”

“His daughter,” said Joan, “has just engaged me as a lady’s maid.”

“What!”

“It will not be quite the same thing as three years ago,” Joan explained. “It is just a cheap way of getting a holiday. I used to know Miss Peters very well, you see. It will be more like traveling as her guest.”

“But—but——” Ashe had not yet overcome his amazement.

“Yes?”

“But what an extraordinary coincidence!”

“Yes. By the way, how did you get the situation? And what put it into your head to be a valet at all? It seems such a curious thing for you to think of doing.”

Ashe was embarrassed.

“I—I—well, you see, the experience will be useful to me, of course, in my writing.”

“Oh! Are you thinking of taking up my line of work? Dukes?”

“No, no—not exactly that.”

“It seems so odd. How did you happen to get in touch with Mr. Peters?”

“Oh, I answered an advertisement.”

“I see.”

Ashe was becoming conscious of an undercurrent of something not altogether agreeable in the conversation. It lacked the gay ease of their first interview. He was not apprehensive lest she might have guessed his secret. There was, he felt, no possible means by which she could have done that. Yet the fact remained that those keen blue eyes of hers were looking at him in a peculiar and penetrating manner. He felt damped.

“It will be nice, being together,” he said feebly.

“Very!” said Joan.

There was a pause.

“I thought I would come and tell you.”

“Quite so.”

There was another pause.

“It seems so funny that you should be going out as a lady’s maid.”

“Yes?”

“But, of course, you have done it before.”

“Yes.”

“The really extraordinary thing is that we should be going to the same people.”

“Yes.”

“It—it’s remarkable, isn’t it?”

“Yes.”

Ashe reflected. No; he did not appear to have any further remarks to make.

“Good-by for the present,” he said.

“Good-by.”

Ashe drifted out. He was conscious of a wish that he understood girls. Girls, in his opinion, were odd.

When he had gone Joan Valentine hurried to the door and, having opened it an inch, stood listening. When the sound of his door closing came to her she ran down the stairs and out into Arundel Street. She went to the Hotel Mathis.

“I wonder,” she said to the sad-eyed waiter, “if you have a copy of the Morning Post?”

The waiter, a child of romantic Italy, was only too anxious to oblige youth and beauty. He disappeared and presently returned with a crumpled copy. Joan thanked him with a bright smile.

Back in her room, she turned to the advertisement pages. She knew that life was full of what the unthinking call coincidences; but the miracle of Ashe having selected by chance the father of Aline Peters as an employer was too much of a coincidence for her. Suspicion furrowed her brow.

It did not take her long to discover the advertisement that had sent Ashe hurrying in a taxicab to the offices of Messrs. Mainprice, Mainprice & Boole. She had been looking for something of the kind.

She read it through twice and smiled. Everything was very clear to her. She looked at the ceiling above her and shook her head.

“You are quite a nice young man, Mr. Marson,” she said softly; “but you mustn’t try to jump my claim. I dare say you need that money too; but I’m afraid you must go without. I am going to have it—and nobody else!”

(TO BE CONTINUED)

Madame Eulalie’s Rare Plums

Madame Eulalie’s Rare Plums