The Strand Magazine, February 1925

JAMES RODMAN bent forward and knocked the ashes out of his pipe. For awhile he sat, silent and pensive, staring into the fire. Then with a little, sudden movement he stooped and patted his dog William, asleep on the rug, and, leaning back, refilled his pipe and lit it. The flame of the match shone for a moment on his strong, capable face. Outside, the storm raged against the window, for it was an eerie night of howling wind and driving rain.

“Do you believe in ghosts?” he asked, abruptly.

I weighed the question thoughtfully. I was a little surprised, for nothing in our previous conversation had suggested the topic.

“Well, I don’t like them, if that’s what you mean. I was butted by one as a child.”

“Ghosts,” said James with some brusqueness. “Not goats.”

“Oh! Do I believe in ghosts?”

“Exactly.”

“Well, yes—and no.”

“That,” said James, “is a fat lot of help. I’ll put it another way. Do you believe in haunted houses? Do you believe that it is possible for a malign influence to envelop a place and work a spell on all who come within its radius?”

“Well——” I hesitated. “Well, no—and yes.” James looked at me with dislike.

“Are you always as bright as this?” he asked, sourly.

“Of course,” I went on, “one has read stories. Henry James’s ‘Turn of the Screw,’ for example. And Dunsany, I think, has one.”

“I’m not talking about fiction, fool. Of course there are thousands of haunted houses in fiction.”

“Well, in real life. . . . Well, look here, I once, as a matter of fact, did meet a man who knew a fellow——”

“I once lived in a haunted house,” he said. If James Rodman has a fault, it is his tendency to be a bad listener. I think it must be the result of always writing those mystery stories of his. You know how the detective in those tales always jumps on his friend and shushes him down if he tries to get a word in edgeways. James has become rather like that. “It cost me five thousand pounds. That is to say, that is the sum I sacrificed by not remaining there. I have spoken to you about my aunt Leila, the one who wrote sentimental novels——”

“De mortuis, you know,” I said, gravely. “Remember she is dead.”

“I know she’s dead, fathead. That’s the whole point of the story. I wasn’t going to say anything against her.”

I was relieved. In past years, you see, I had frequently heard James Rodman speak his mind on the subject of his aunt Leila and her books, and I was fearing another outburst. For James, I regret to say, was ashamed of his gifted relative. The lush sentimentalism of Leila May Pinckney, which was so dear to her enormous public, revolted him. He had always held rigid views on the art of the novel, and maintained that the artist should not descend to sloppy love-stories but should stick austerely to revolvers, cries in the night, missing papers, mysterious Chinamen, and dead bodies (with or without gash in throat).

I had never myself read anything by the late Miss Pinckney, but I knew that by those entitled to judge she had been regarded as pre-eminent in her particular form of literature. The critics usually headed their reviews of her books with the words:—

ANOTHER PINCKNEY

Or, sometimes, more offensively:—

ANOTHER PINCKNEY!!!

And once, dealing with, I think, “The Love Which Prevails,” the literary expert of the Scrutinizer had compressed his entire critique into the single phrase “Oh, God!”

“What I was going to say, when you interrupted me,” resumed James, “was that when my aunt Leila died I found she had left me five thousand pounds and the house in the country where she had lived for the last twenty years of her life.”

He paused.

“Fancy that!” I said.

“Twenty years,” repeated James. “Grasp that, for it has a vital bearing on what follows. Twenty years, mind you, and she turned out two novels and twelve short stories regularly every year, besides a monthly page of Advice to Young Girls in one of the magazines. That is to say, forty of my aunt Leila’s novels and no fewer than two hundred and forty of her short stories were written under the roof of Honeysuckle Cottage.”

“A pretty name,” I said.

“It was a condition of the will that I should reside there for the whole of the first year and for six months in every year that followed. Failing to do this, I was to forfeit the five thousand pounds.”

“It must be great fun making a freak will,” I said, meditatively. “I often wish I was rich enough to do it.”

“This wasn’t a freak will. The condition was perfectly intelligible. Aunt Leila was a firm believer in the influence of environment. She inserted this clause in order to compel me to move from London to the country. She had always objected to my living in London, maintaining that it hardened me and made my outlook on life sordid. She never liked my stuff, poor soul.”

“I see.”

“So I went down to Honeysuckle Cottage and—— Well, I’ll tell you the whole story.”

JAMES’S first impressions of Honeysuckle Cottage were, he tells me, wholly favourable. He was delighted with the place. It was a low, rambling, picturesque old house with funny little chimneys and a red roof, placed in the middle of the most charming country. With its oak beams, its trim garden, its trilling birds, and its rose-hung porch, it was the ideal spot for a writer. It was just the sort of place, he reflected whimsically, which his aunt had loved to write about in her books. Even the apple-cheeked old housekeeper who attended to his needs might have stepped straight out of one of them.

It seemed to James that his lot had been cast in pleasant places. He had brought down his books, his pipes, and his golf-clubs, and was hard at work finishing the best thing he had ever done. “The Secret Nine” was the title of it: and on the beautiful summer afternoon on which this story opens he was in the study, hammering away at his typewriter, at peace with the world. The machine was running sweetly, the new tobacco he had bought the day before was proving admirable, and he was moving on all six cylinders to the end of a chapter.

He shoved in a fresh sheet of paper, chewed his pipe thoughtfully for a moment, then wrote rapidly.

For an instant Lester Gage thought that he must have been mistaken. Then the noise came again, faint but unmistakable—a soft scratching on the outer panel.

His mouth set in a grim line. Silently, like a panther, he made one quick step to the desk, noiselessly opened a drawer, drew out his automatic. After that affair of the poisoned needle he was taking no chances. Still in dead silence, he tiptoed to the door; then, flinging it suddenly open, he stood there, his weapon poised.

On the mat stood the most beautiful girl he had ever beheld. A veritable child of Faery. She eyed him for a moment with a saucy smile; then with a pretty, roguish look of reproof she shook a dainty forefinger at him.

“I believe you’ve forgotten me, Mr. Gage!” she fluted with a mock severity which her eyes belied.

James stared at the paper dumbly. He was utterly perplexed. He had not had the slightest intention of writing anything like this. To begin with, it was his unbroken rule never to permit girls to enter his stories. He held that a detective story should have no heroine. Heroines only held up the action and tried to flirt with the hero when he should have been busy looking for clues, and then went and let the villain kidnap them by some childishly simple trick. No, no girls for James.

And yet here was this creature with her saucy smile and her dainty forefinger horning in at the most important point in the story. It was uncanny.

He looked once more at his scenario. No, the scenario was all right. In perfectly plain words it stated that what happened when the door opened was that a dying man fell in, and after gasping “The beetle! Tell Scotland Yard that the blue beetle is——” expired on the hearth-rug, leaving Lester Gage not unnaturally somewhat mystified. Nothing whatever about any beautiful girls.

In a curious mood of irritation James scratched out the offending passage, wrote in the necessary corrections, and put the cover on the machine. It was at this point that he heard William whining.

The only blot on this Paradise which James had so far been able to discover was the infernal dog William. Belonging nominally to the gardener, on the very first morning he had adopted James by acclamation. And he maddened and infuriated James. He had a habit of coming and whining under the window when James was at work. The latter would ignore this as long as he could, then, when the thing became insupportable, would bound out of his chair, to see the animal standing on the gravel, gazing expectantly up at him with a stone in his mouth. William had a weak-minded passion for chasing stones, and on the first day James, in a rash spirit of camaraderie, had flung one for him. Since then James had thrown no more stones, but he had thrown any number of other solids, and the garden was littered with objects ranging from match-boxes to a plaster statuette of the young Joseph prophesying before Pharaoh. And still William came and whined, an optimist to the last.

The whining, coming now at a moment when he felt irritable and unsettled, acted on James much as the scratching on the door had acted on Lester Gage. Silently, like a panther, he made one quick step to the mantelpiece, removed from it a china mug bearing the legend “A Present from Clacton-on-Sea,” and crept to the window.

And as he did so a voice outside said, “Go away, sir, go away!” and there followed a short, high-pitched bark which was certainly not William’s. William was a mixture of Airedale, setter, bull-terrier, and mastiff; and, when in vocal mood, favoured the mastiff side of his family.

James peered out. There on the porch stood a girl in blue. She held in her arms a small fluffy white dog, and she was endeavouring to foil the upward movement towards this of the blackguard William. William’s mentality had been arrested some years before at the point where he imagined that everything in the world had been created for him to eat. A bone, a boot, a steak, the back wheel of a bicycle—it was all one to William. If it was there, he tried to eat it. He had even made a plucky attempt to devour the remains of the young Joseph prophesying before Pharaoh. And it was perfectly plain now that he regarded the curious wriggling object in the girl’s arms purely in the light of a snack to keep body and soul together till dinner-time.

“William!” bellowed James.

William looked courteously over his shoulder with eyes that beamed with the pure light of a life’s devotion; wagged the whip-like tail which he had inherited from his bull-terrier ancestor, and resumed his intent scrutiny of the fluffy dog.

“Oh, please!” cried the girl. “This great rough dog is frightening poor Toto.”

The man of letters and the man of action do not always go hand in hand, but practice had made James perfect in handling with a swift efficiency any situation that involved William. A moment later that canine moron, having received the present from Clacton in the short ribs, was scuttling round the corner of the house, and James had jumped through the window and was facing the girl.

She was an extraordinarily pretty girl. Very sweet and fragile she looked as she stood there under the honeysuckle with the breeze ruffling a tendril of golden hair that strayed from beneath her coquettish little hat. Her eyes were very big and very blue, her rose-tinted face becomingly flushed. All wasted on James, though. He disliked all girls, and particularly the sweet, droopy type.

“Did you want to see somebody?” he asked, stiffly.

“Just the house,” said the girl. “If it wouldn’t be giving any trouble. I do so want to see the room where Miss Pinckney wrote her books. This is where Leila May Pinckney used to live, isn’t it?”

“Yes. I am her nephew. My name is James Rodman.”

“Mine is Rose Maynard.”

James led the way into the house, and she stopped with a cry of delight on the threshold of the morning-room.

“Oh, how too perfect!” she cried. “So this was her study?”

“Yes.”

“What a wonderful place it would be for you to think in, if you were a writer, too!”

James held no high opinion of women’s literary taste, but nevertheless he was conscious of an unpleasant shock.

“I am a writer,” he said, coldly. “I write detective stories.”

“I—I’m afraid——” She blushed. “I’m afraid I don’t often read detective stories.”

“You no doubt prefer,” said James, still more coldly, “the sort of thing my aunt used to write.”

“Oh, I love her stories!” cried the girl, clasping her hands ecstatically. “Don’t you?”

“I cannot say that I do.”

“What!”

“They are pure apple-sauce,” said James, sternly. “Just nasty blobs of sentimentality, thoroughly untrue to life.”

The girl stared.

“Why, that’s just what’s so wonderful about them, their trueness to life! You feel they might all have happened. I don’t understand what you mean.”

They were walking down the garden now. James held the gate open for her and she passed through into the road.

“Well, for one thing,” he said, “I decline to believe that a marriage between two young people is invariably preceded by some violent and sensational experience in which they both share.”

“Are you thinking of ‘Scent o’ the Blossom,’ where Edgar saves Maud from drowning?”

“I am thinking of every single one of my aunt’s books.” He looked at her curiously. He had just got the solution of a mystery which had been puzzling him for some time. Almost from the moment he had set eyes on her she had seemed somehow strangely familiar. It now suddenly came to him why it was that he disliked her so much. “Do you know,” he said, “you might be one of my aunt’s heroines yourself. You’re just the sort of girl she used to love to write about.”

Her face lit up.

“Oh, do you really think so?” She hesitated. “Do you know what I have been feeling ever since I came here? I’ve been feeling that you are exactly like one of Miss Pinckney’s heroes.”

“No, I say, really!” said James, revolted.

“Oh, but you are. When you jumped through that window it gave me quite a start. You were so exactly like Claude Masterson in ‘Heather o’ the Hills.’ ”

“I have not read ‘Heather o’ the Hills,’ ” said James, with a shudder.

“He was very strong and quiet, with deep, dark, sad eyes.”

James did not explain that his eyes were sad because her society gave him a pain in the neck. He merely laughed scornfully.

“So now, I suppose,” he said, “a car will come and knock you down and I shall carry you gently into the house and lay you—— Look out!” he cried.

It was too late. She was lying in a little huddled heap at his feet. Round the corner a large car had come bowling, keeping with an almost affected precision to the wrong side of the road. It was now receding into the distance, the occupant of the tonneau, a stout, red-faced gentleman in a fur coat, leaning out over the back. He had bared his head—not, one fears, as a pretty gesture of respect and regret, but because he was using his hat to hide the number-plate.

The dog Toto was, unfortunately, uninjured.

James carried the girl gently into the house and laid her on the sofa in the morning-room. He rang the bell and the apple-cheeked housekeeper appeared.

“Send for the doctor,” said James. “There has been an accident.”

The housekeeper bent over the girl.

“Eh, dearie, dearie!” she said. “Bless her sweet, pretty face!”

The gardener, he who technically owned William, was routed out from among the young lettuces and told to fetch Dr. Brady. He separated his bicycle from William, who was making a light meal off the left pedal, and departed on his mission. Dr. Brady arrived. And in due course he made his report.

“No bones broken, but a number of nasty bruises. And, of course, the shock. She will have to stay here for some time, Rodman. Can’t be moved.”

“Stay here! But she can’t. It isn’t proper.”

“Your housekeeper will act as a chaperon.”

The doctor sighed. He was a man of middle age with side-whiskers.

“A beautiful girl, that, Rodman,” he said.

“I suppose so,” said James.

“A sweet, beautiful girl. An elfin child.”

“A what?” cried James, starting. This imagery was very foreign to Dr. Brady as he knew him. On the only previous occasion on which they had had any extended conversation, the doctor had talked exclusively about the effect of too much proteins on the gastric juices.

“An elfin child. A tender, fairy creature. When I was looking at her just now, Rodman, I nearly broke down. Her little hand lay on the coverlet like some white lily floating on the surface of a still pool, and her dear, trusting eyes gazed up at me——”

He pottered off down the garden, still babbling, and James stood staring after him blankly. And slowly, like some cloud athwart a summer sky, there crept over James’s heart the chill shadow of a nameless fear.

IT was about a week later that Mr. Andrew McKinnon, the senior partner in the well-known firm of literary agents, McKinnon and Gooch, sat in his office in Chancery Lane, frowning thoughtfully over a telegram. He rang the bell.

“Ask Mr. Gooch to step in here.”

He resumed his study of the telegram.

“Oh, Gooch,” he said, when his partner appeared, “I’ve just had a curious wire from young Rodman. He seems to want to see me very urgently.”

Mr. Gooch read the telegram.

“Written under the influence of some strong mental excitement,” he agreed. “I wonder why he doesn’t come to the office if he wants to see you so badly?”

“He’s working very hard, finishing that novel for Prodder and Wiggs. Can’t leave it, I suppose. Well, it’s a nice day. If you will look after things here, I think I’ll motor down and let him give me lunch.”

As Mr. McKinnon’s car reached the crossroads a mile from Honeysuckle Cottage, he was aware of a gesticulating figure by the hedge. He stopped the car.

“Morning, Rodman.”

“Thank God you’ve come!” said James. It seemed to Mr. McKinnon that the young man looked paler and thinner. “Would you mind walking the rest of the way? There’s something I want to speak to you about.”

Mr. McKinnon alighted, and James, as he glanced at him, felt cheered and encouraged by the very sight of the man. The literary agent was a grim, hard-bitten person, to whom, when he called at their offices to arrange terms, editors kept their faces turned so that they might at least retain their back collar-studs. There was no sentiment in Andrew McKinnon. Editresses of Society papers practised their blandishments on him in vain, and many a publisher had woken screaming in the night, dreaming that he was signing a McKinnon contract.

“ WELL, Rodman,” he said, “Prodder and Wiggs have agreed to our terms. I was writing to tell you so when your wire arrived. I had a lot of trouble with them, but it’s fixed at twenty per cent. rising to twenty-five, and two hundred pounds advance royalties on day of publication.”

“Good,” said James, absently. “Good. McKinnon, do you remember my aunt, Leila May Pinckney?”

“Remember her? Why, I was her agent all her life.”

“Of course. Then you know the sort of tripe she wrote.”

“No author,” said Mr. McKinnon, reprovingly, “who pulls down a steady twenty thousand pounds a year writes tripe.”

“Well, anyway, you know her stuff.”

“Who better?”

“When she died she left me five thousand pounds and her house, Honeysuckle Cottage. I’m living there now. McKinnon, do you believe in haunted houses?”

“No.”

“Yet I tell you solemnly that Honeysuckle Cottage is haunted!”

“By your aunt?” said Mr. McKinnon, surprised.

“By her influence. There’s a malignant spell over the place. A sort of miasma of sentimentalism. Everybody who enters it succumbs.”

“Tut, tut! You mustn’t have these fancies.”

“They aren’t fancies.”

“You aren’t seriously meaning to tell me——”

“Well, how do you account for this? That book you were speaking about, which Prodder and Wiggs are to publish, ‘The Secret Nine.’ Every time I sit down to write it, a girl keeps trying to sneak in.”

“Into the room?”

“Into the story.”

“You don’t want a love-interest in your sort of book,” said Mr. McKinnon, shaking his head. “It delays the action.”

“I know it does. And every day I have to keep shooing this infernal female out. An awful girl, McKinnon. A soppy, soupy, treacly, drooping girl with a roguish smile. This morning she tried to butt in on the scene where Lester Gage is trapped in the den of the mysterious leper.”

“No!”

“She did, I assure you. I had to rewrite three pages before I could get her out of it. And that’s not the worst. Do you know, McKinnon, that at this moment I am actually living the plot of a typical Leila May Pinckney novel in just the setting she always used? And, my God! I can see the happy ending coming nearer every day. A week ago a girl was knocked down by a car at my door, and I’ve had to put her up. And every day I realize more clearly that, sooner or later, I shall ask her to marry me.”

“Don’t do it,” said Mr. McKinnon, a stout bachelor. “You’re too young to marry.”

“So was Methuselah,” said James, a stouter. “But all the same, I know I’m going to do it. It’s the influence of this awful house weighing upon me. I feel like an egg-shell in a maelstrom. I am being sucked on by a force too strong for me to resist. This morning I found myself kissing her dog!”

“No!”

“I did. And I loathe the little beast. Yesterday I got up at dawn and plucked a nosegay of flowers for her, wet with the dew.”

“Rodman!”

“It’s a fact. I laid them at her door and went downstairs kicking myself all the way. And there in the hall was the apple-cheeked housekeeper regarding me archly. If she didn’t murmur ‘Bless their sweet young hearts!’ my ears deceived me.”

“Why don’t you pack up and leave?”

“If I do, I lose the five thousand pounds.”

“Ah!” said Mr. McKinnon.

“I can understand what has happened. It’s the same with all haunted houses. My aunt’s subliminal ether-vibrations have woven themselves into the texture of the place, creating an atmosphere which forces the ego of all who come in contact with it to attune themselves to it. It’s either that or something to do with the fourth dimension.”

Mr. McKinnon laughed scornfully.

“Tut, tut!” he said, testily. “This is pure imagination. What has happened is that you’ve been working too hard. You’ll see this precious atmosphere of yours will have no effect on me.”

“That’s exactly why I asked you to come down. I hoped you might break the spell.”

“I will that,” said Mr. McKinnon, jovially.

The fact that the literary agent spoke little at lunch caused James no apprehension. Mr. McKinnon was ever a silent trencherman. From time to time James caught him stealing a glance at the girl, who was well enough to come down to meals now, limping pathetically; but he could read nothing in his face. And yet the mere look of his face was a consolation. It was so solid, so matter-of-fact, so exactly like an unemotional coco nut.

“You’ve done me good,” said James, with a sigh of relief, as he escorted the agent down the garden to his car after lunch. “I felt all along that I could rely on your rugged common sense. The whole atmosphere of the place seems different now.”

Mr. McKinnon did not speak for a moment. He seemed to be plunged in thought.

“Rodman,” he said, as he got into his car, “I’ve been thinking over that suggestion of yours of putting a love-interest into ‘The Secret Nine.’ I think you’re wise. The story needs it. After all, what is there greater in the world than love? Love—love—aye, it’s the sweetest word in the language. Put in a heroine and let her marry Lester Gage.”

“If,” said James, grimly, “she does succeed in worming her way in, she’ll jolly well marry the mysterious leper. But, look here, I don’t understand——”

“It was seeing that girl that changed me,” proceeded Mr. McKinnon. And as James stared at him aghast, tears suddenly filled his hard-boiled eyes. He openly snuffled. “Aye, seeing her sitting there under the roses with all that smell of honeysuckle and all. And the birdies singing so sweet in the garden and the sun lighting up her bonnie face. The puir wee lass!” he muttered, dabbing at his eyes. “The puir bonnie wee lass! Rodman,” he said, his voice quivering, “I’ve decided that we’re being hard on Prodder and Wiggs. Wiggs has had sickness in his home lately. We mustn’t be hard on a man who’s had sickness in his home, hey, laddie? No, no! I’m going to take back that contract and alter it to a flat twelve per cent. and no advance royalties.”

“What!”

“But you sha’n’t lose by it, Rodman. No, no, you sha’n’t lose by it, my mannie. I am going to waive my commission. The puir bonnie wee lass!”

The car rolled off down the road. Mr. McKinnon, seated in the back, was blowing his nose violently.

“This is the end!” said James.

I WANT you to appreciate James’s position. You who read this are probably a happy married man, constitutionally unable to realize the intensity of the instinct for self-preservation which animates Nature’s bachelors in time of peril. James, you feel, was making a lot of fuss about nothing. Charming girl—pretty as a picture—big blue eyes—— A lucky dog, you consider.

But James was so constructed as to be unable to look at the matter in this way. He had a congenital horror of matrimony. Though a young man, he had allowed himself to develop a great many habits which were as the breath of life to him; and these habits, he knew instinctively, a wife would shoot to pieces within a week of the end of the honeymoon.

James liked to breakfast in bed: and, having breakfasted, to smoke in bed and knock the ashes out on the carpet. What wife would tolerate this practice?

James liked to pass his days in a tennis shirt, grey flannel trousers, and slippers. What wife ever rests until she has enclosed her husband in a stiff collar, tight boots, and a morning suit and taken him with her to thés musicales?

These and a thousand other thoughts of the same kind flashed through the unfortunate young man’s mind as the days went by. And every day that passed seemed to draw him nearer to the brink of the chasm. Fate appeared to be taking a malicious pleasure in making things as difficult for him as possible. Now that the girl was well enough to leave her bed, she spent her time sitting in a chair on the sun-sprinkled porch, and James had to read to her. And poetry at that. And not the jolly, wholesome sort of poetry the boys are turning out nowadays, either—good, honest stuff about sin and gas-works and decaying corpses, but the old-fashioned kind with rhymes in it, dealing almost exclusively with love.

The weather, moreover, continued superb. The honeysuckle cast its sweet scent on the gentle breeze; the roses over the porch stirred and nodded; the flowers in the garden were lovelier than ever; the birds sang their little throats sore. And every evening there was a magnificent sunset. It was almost as if Nature were doing it on purpose.

At last James intercepted Dr. Brady as he was leaving after one of his visits and put the thing to him squarely.

“When is that girl going?”

The doctor patted him on the arm.

“Not yet, Rodman,” he said, in a low, understanding voice. “No need to worry yourself about that. Mustn’t be moved for days and days and days—I might almost say weeks and weeks and weeks.”

“Weeks and weeks!” cried James.

“And weeks,” said Dr. Brady. He prodded James roguishly in the abdomen. “Good luck to you, my boy; good luck to you,” he said.

It was some small consolation to James that the mushy physician immediately afterwards tripped over William on his way down the path and broke his stethoscope. When a man is up against it like James, every little helps.

He was walking dismally back to the house after this conversation when he was met by the apple-cheeked housekeeper.

“The little lady would like to speak to you, sir,” said the apple-cheeked exhibit, rubbing her hands.

“Would she?” said James, hollowly.

“So sweet and pretty she looks, sir; oh, sir, you wouldn’t believe! Like a blessed angel sitting there with her dear eyes all a-shining——”

“Don’t do it!” cried James, with extraordinary vehemence. “Don’t do it!”

He found the girl propped up on the cushions and thought once again how singularly he disliked her. And yet, even as he thought this, some force against which he had to fight madly was whispering to him: “Go to her and take that little hand! Breathe into that little ear the burning words that will make that little face turn away, crimsoned with blushes!” He wiped a bead of perspiration from his forehead and sat down.

“Mrs. Stick-in-the-Mud—what’s her name?—says you want to see me.”

The girl nodded.

“I’ve had a letter from Uncle Henry. I wrote to him as soon as I was better and told him what had happened, and he is coming here to-morrow morning.”

“Uncle Henry?”

“That’s what I call him, but he’s really no relation. He is my guardian. He and daddy were officers in the same regiment, and when daddy was killed, fighting on the Afghan frontier, he died in Uncle Henry’s arms and with his last breath begged him to take care of me.”

James started. A sudden wild hope had awoken in his heart. Years ago, he remembered, he had read a book of his aunt’s, entitled “Rupert’s Legacy,” and in that book——

“I’m engaged to marry him,” said the girl, quietly.

“Wow!” shouted James.

“What?” asked the girl, startled.

“Touch of cramp,” said James. He was thrilling all over. That wild hope had been realized.

“It was daddy’s dying wish that we should marry,” said the girl.

“And dashed sensible of him, too. Dashed sensible,” said James, warmly.

“And yet,” she went on, a little wistfully, “I sometimes wonder——”

“Don’t,” said James. “Don’t. You must respect a father’s dying wish. So he’s coming here to-morrow, is he? Capital, capital! To lunch, I suppose? Excellent! I’ll run down and tell Mrs. Who-is-it to lay in another chop.”

IT was with a gay and uplifted heart that James strolled the garden and smoked his pipe next morning. A great cloud seemed to have rolled itself away from him. Everything was for the best in the best of all possible worlds. He had finished “The Secret Nine” and shipped it off to Mr. McKinnon, and now as he strolled there was shaping itself in his mind a corking plot about a man with only half a face who lived in a secret den under a house near Kennington Oval and terrorized London with a series of shocking murders. And what made them so shocking was the fact that each of the victims, when discovered, was found to have only half a face, too. The rest had been chipped off, presumably by some blunt instrument.

The thing was coming out magnificently, when suddenly his attention was diverted by a piercing scream. Out of the bushes fringing the river that ran beside the garden burst the apple-cheeked housekeeper.

“Oh, sir! Oh, sir! Oh, sir!”

“What is it?” demanded James, irritably.

“Oh, sir! Oh, sir! Oh, sir!”

“Yes, and then what?”

“The little dog, sir. He’s in the river.”

“Well, whistle him to come out.”

“Oh, sir, do come quick. He’ll be drowned.”

James followed her through the bushes, taking off his coat as he went. He was saying to himself: “I will not rescue this dog. I do not like the dog, it is high time he had a bath, and in any case it would be much simpler to stand on the bank and fish for him with a rake. Only an ass out of a Leila May Pinckney book would dive into a beastly river to save——”

At this point he dived. Toto, alarmed by the splash, swam rapidly for the bank, but James was too quick for him. Grasping him firmly by the neck, he scrambled ashore and ran for the house, followed by the housekeeper.

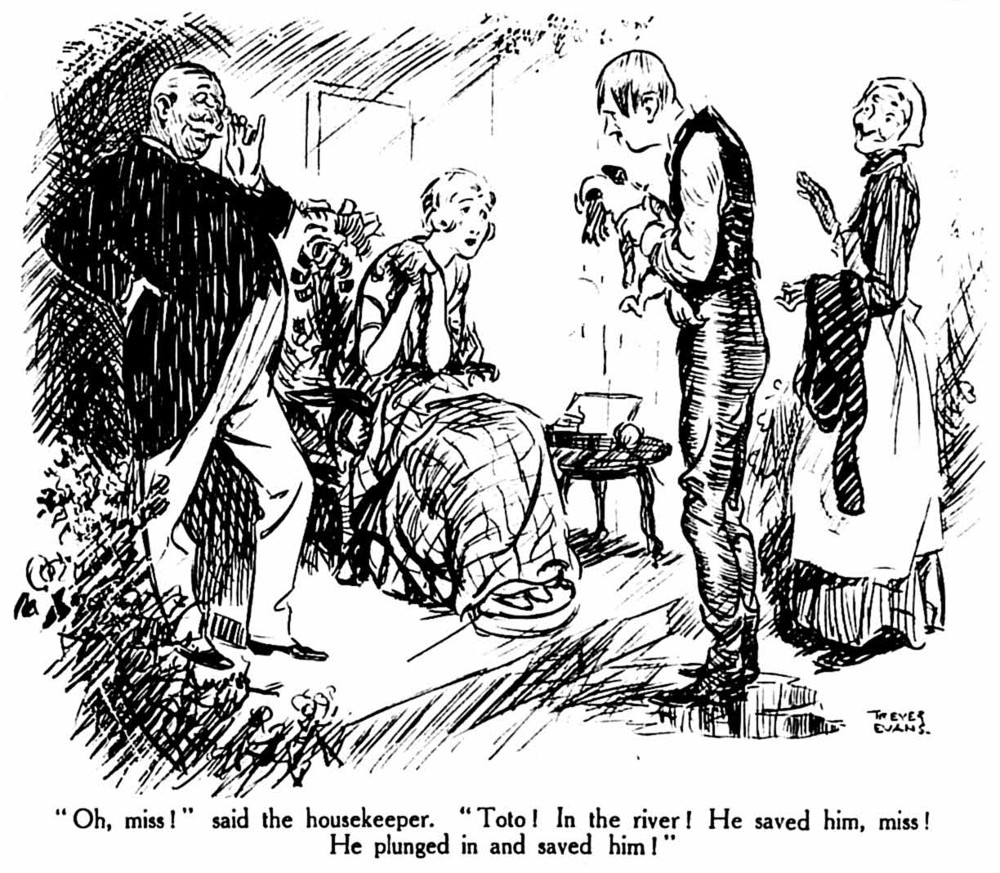

The girl was seated on the porch. Over her there bent the tall, soldierly figure of a man with keen eyes and greying hair. The housekeeper raced up.

“Oh, miss! Toto! In the river! He saved him, miss! He plunged in and saved him!”

The girl drew a quick breath.

“Gallant, damme! By Jove! By gad! Yes, gallant, by George!” exclaimed the soldierly man.

The girl seemed to wake from a reverie.

“Uncle Henry, this is Mr. Rodman. Mr. Rodman, my guardian, Colonel Carteret.”

“Proud to meet you, sir,” said the Colonel, his honest blue eyes glowing as he fingered his short, crisp moustache. “As fine a thing as I ever heard of, damme!”

“Yes. You are brave—brave,” the girl whispered.

“I am wet—wet,” said James, and went upstairs to change his clothes.

THE girl did not appear at lunch, and James had to undertake the task of entertaining Colonel Carteret by himself. It was not a particularly easy task, for the man appeared silent and preoccupied. James, anxious to play the host, tried to draw him out on golf, Cubist art, the Czecho-Slovakian problem, life in the East, the dance craze, the growing unrest of the age, the treatment of hens in sickness, modern music, hydrotherapy as a cure for rheumatism, and the weather, but was countered by silent nods. From time to time the Colonel, pulling at his crisp moustache, seemed about to say something, but never got farther than a brief military clearing of the throat. Once James, catching his eye as he reached for the mustard, found that the elder man was scrutinizing him closely.

The meal concluded, he produced cigarettes, and for a while the silence remained unbroken. Then Colonel Carteret bent forward, his clean-cut face grave.

“Rodman,” he said, “I should like to speak to you.”

“Yes?” said James, thinking it was about time.

“Rodman,” said Colonel Carteret. “Or, rather, George. I may call you George?” he added, with a sort of wistful diffidence that had a singular charm.

“Certainly, if you wish it,” replied James, civilly. “Though my name is James.”

“James, eh? Well, well, it amounts to the same thing, eh, what, damme, by gad?” said the Colonel with a momentary return of his bluff, soldierly manner. Well, then, James, I have something that I wish to say to you. Did Miss Maynard—did Rose happen to tell you anything about myself in—er—in connection with herself?”

“She mentioned that you and she were engaged to be married.”

The Colonel’s tightly-drawn lips quivered. “No longer,” he said.

“What!”

“No, John, my boy——”

“James.”

“No, James, my boy, no longer. While you were upstairs changing your clothes, she told me—breaking down, poor child, as she spoke—that she wished our engagement to be at an end.”

James half rose from the table, his cheeks blanched.

“You don’t mean that!” he gasped.

Colonel Carteret nodded. He was staring out of the window, his fine eyes set in a look of pain.

“But this is nonsense,” cried James. “This is absurd. She—she mustn’t be allowed to chop and change like this. I mean to say, it—it isn’t fair——”

“Don’t think of me, my boy.”

“I’m not—I mean, did she give any reason?”

“Her eyes did.”

“Her what did?”

“Her eyes, when she looked at you on the porch, as you stood there—young, heroic—having just saved the life of the dog she loves. It is you who have won that tender heart, my boy.”

“Now listen,” protested James. “You aren’t going to sit there and tell me that a girl falls in love with a man just because he saves her dog from drowning?”

“Why, surely,” said Colonel Carteret, surprised. “What better reason could she have?” He sighed. “It is the old, old story, my boy. Youth to Youth. I am an old man—I should have known—I should have foreseen—yes, Youth to Youth.”

“You aren’t a bit old.”

“Yes, yes.”

“No, no.”

“Yes, yes.”

“Don’t keep on saying ‘Yes, yes,’ ” cried James, clutching at his hair. “Besides, she wants a steady old buffer—a steady, sensible man of medium age—to look after her.”

Colonel Carteret shook his head with a gentle smile.

“This is mere quixotry, my boy. It is splendid of you to take this attitude, but no, no.”

“Yes, yes.”

“No, no.” He gripped James’s hand for an instant, then rose and walked to the door. “That is all I wished to say, Tom.”

“James.”

“James. I just thought that you ought to know how matters stood. Go to her, my boy, go to her, and don’t let any thought of an old man’s broken dream keep you from pouring out what is in your heart. I am an old soldier, lad, an old soldier. I have learned to take the rough with the smooth. But I think—I think I will leave you now. I—I should—should like to be alone for awhile. If you need me, you will find me in the raspberry bushes.”

He paused at the door; smiled that brave, gentle smile of his once again, and was gone. A soldier and a gentleman. It is not only on the stricken field of battle that the officers of the King’s Own Royal Punjabi Light Cavalry are trained to bear themselves like men.

HE had scarcely gone when James, also, left the room. He took his hat and stick and walked blindly out of the garden, he knew not whither. His brain was numbed. Then, as his powers of reasoning returned, he told himself that he should have foreseen this ghastly thing. If there was one type of character over which Leila May Pinckney had been wont to spread herself, it was the pathetic guardian who loves his ward but renounces her to the younger man. No wonder the girl had broken off the engagement. Any elderly guardian who allowed himself to come within a mile of Honeysuckle Cottage was simply asking for it.

And then as he turned to walk back, a sort of dull defiance gripped James. Why, he asked, should he allow himself to be put upon in this manner? If the girl liked to throw over this man, why should he be the goat?

He saw his way clearly now. He just wouldn’t do it, that was all. And if they didn’t like it they could lump it.

Full of a new fortitude, he strode in at the gate. A tall, soldierly figure emerged from the raspberry bushes and came to meet him.

“Well?” said Colonel Carteret.

“Well?” said James, defiantly.

“Am I to congratulate you?”

James caught his keen blue eye and hesitated. It was not going to be so simple as he had supposed.

“Well—er——” he said.

Into the keen blue eyes there came a look that James had not seen there before. It was the stern, hard look which (probably) had caused men to bestow upon this old soldier the name of Cold-Steel Carteret.

“You have not asked Rose to marry you?”

“Er—no. Not yet.”

The keen blue eyes grew keener and bluer.

“Rodman,” said Colonel Carteret, in a strange, quiet voice, “I have known that little girl since she was a tiny child. For years she has been all in all to me. Her father died in my arms, and with his last breath bade me see that no harm came to his darling. I have nursed her through mumps, measles—aye, and chicken-pox, and I live but for her happiness.” He paused, with a significance that made James’s toes curl. “Rodman,” he said, “do you know what I would do to any man who trifled with that little girl’s affections?” He reached in his hip-pocket, and an ugly-looking revolver glittered in the sunlight. “I would shoot him like a dog.”

“Like a dog?” faltered James.

“Like a dog,” said Colonel Carteret. He took James’s arm and turned him towards the house. “She is on the porch. Go to her. And if——” He broke off. “But, tut,” he said, in a kindlier tone, “I am doing you an injustice, my boy. I know it.”

“Oh, you are,” said James, fervently.

“Your heart is in the right place.”

“Oh, absolutely,” said James.

“Then go to her, my boy. Later on you may have something to tell me. If so, you will find me in the strawberry beds.”

IT was very cool and fragrant on the porch. Overhead, little breezes played and laughed among the roses. Somewhere in the distance sheep-bells tinkled, and, in the shrubbery a thrush was singing its evensong. Seated in her chair behind a wicker table laden with tea-things, Rose Maynard watched James as he shambled up the path.

“Tea’s ready,” she called, gaily. “Where is Uncle Henry?” A look of pity and distress flitted for a moment over her flower-like face. “Oh, I—I forgot,” she faltered.

“He is in the strawberry beds,” said James, in a low voice.

She nodded unhappily.

“Of course, of course. Oh, why is life like this?” James heard her whisper.

He sat down. He looked at the girl. She was leaning back with closed eyes, and he had thought he had never seen such a little squirt in his life. The idea of passing his remaining days in her society revolted him. He was stoutly opposed to the idea of marrying anyone; but if, as happens to the best of us, he ever was compelled to perform the wedding-glide, he had always hoped it would be with some lady golf champion who would help him with his putting, and thus, by bringing his handicap down a notch or two, enable him to save something from the wreck, so to speak. But to link his lot with a girl who read his aunt’s books and liked them; a girl who could tolerate the presence of the dog Toto; a girl who clasped her hands in pretty, childish joy when she saw a nasturtium in bloom—it was too much.

Nevertheless, he took her hand and began to speak.

“Miss Maynard—Rose——”

She opened her eyes and cast them down. A flush had come into her cheeks. The dog Toto at her side sat up and begged for cake, disregarded.

“Let me tell you a story. Once upon a time there was a lonely man who lived in a cottage all by himself——”

He stopped. Was it James Rodman who was talking this bilge?

“Yes?” whispered the girl.

“But one day there came to him out of nowhere a little fairy princess. She——”

He stopped again, but this time not because of the sheer shame of listening to his own voice. What caused him to interrupt his tale was the fact that at this moment the tea-table suddenly began to rise slowly in the air, tilting as it did so a considerable quantity of hot tea on to the knees of his trousers.

“Ouch!” cried James, leaping.

The table continued to rise, and then fell sideways, revealing the homely countenance of William, who, concealed by the cloth, had been taking a nap beneath it. He moved slowly forward, his eyes on Toto. For many a long day William had been desirous of putting to the test, once and for all, the problem of whether Toto was edible or not. Sometimes he thought yes; at other times no. Now seemed an admirable opportunity for a definite decision. He advanced on the object of his experiment, making a low whistling noise through his nostrils, not unlike a boiling kettle. And Toto, after one long look of incredulous horror, tucked his shapely tail between his legs and, turning, raced for safety. He had laid a course in a bee-line for the open garden gate, and William, shaking a dish of marmalade off his head a little petulantly, galloped ponderously after him.

Rose Maynard staggered to her feet.

“Oh, save him!” she cried.

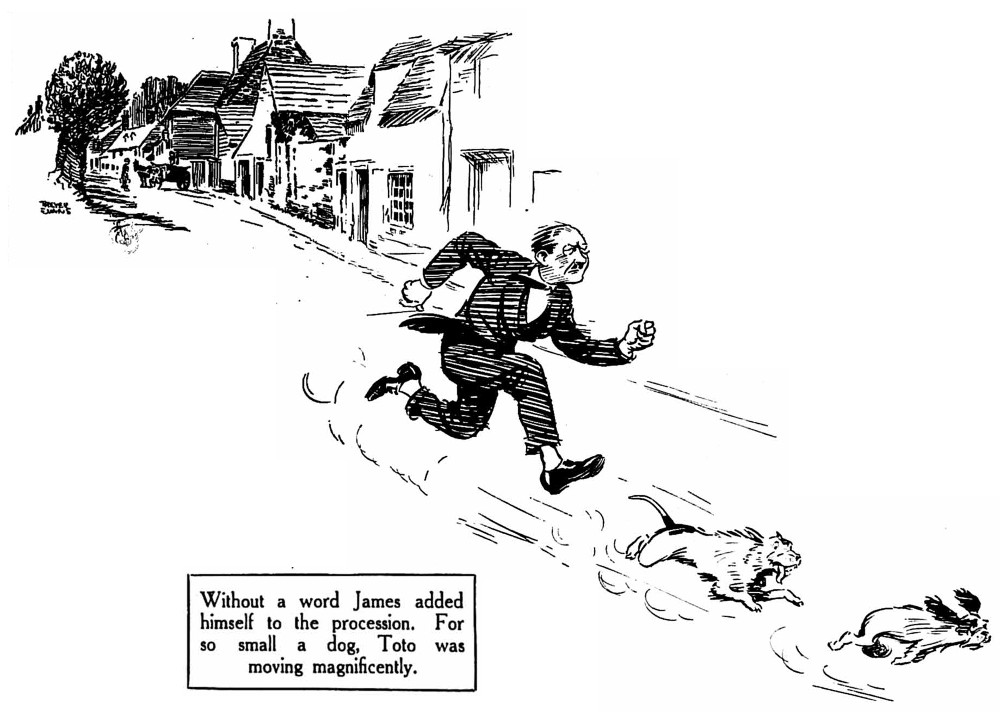

Without a word James added himself to the procession. His interest in Toto was but tepid. What he wanted was to get near enough to William to discuss with him that matter of the tea on his trousers. He reached the road, and found that the order of the runners had not changed. For so small a dog, Toto was moving magnificently. A cloud of dust rose as he skidded round the corner. William followed. James followed William.

And so they passed Farmer Birkett’s barn, Farmer Giles’s cow-shed, the place where Farmer Willetts’s pigsty used to be before the big fire, and the Bunch of Grapes public-house, Jno. Biggs, propr., licensed to sell tobacco, wines, and spirits. And it was as they were turning down the lane that leads past Farmer Robinson’s chicken-run that Toto, thinking swiftly, bolted abruptly into a small drain-pipe.

“William!” roared James, coming up at a canter. He stopped to pluck a branch from the hedge and swooped darkly on.

William had been crouching before the pipe, making a noise like a bassoon into its interior; but now he rose and came beamingly to James. His eyes were aglow with chumminess and affection; and, placing his forefeet on James’s chest, he licked him three times on the face in rapid succession.

And, as he did so, something seemed to snap in James. The scales seemed to fall from James’s eyes. For the first time he saw William as he really was, the authentic type of dog who saves his master from a frightful peril. A wave of emotion swept over him.

“William,” he muttered. “William!”

William was making an early supper off a half-brick he had found in the road. James stooped and patted him fondly.

“William,” he whispered, “you knew when the time had come to change the conversation, didn’t you, old boy?” He straightened himself. “Come, William,” he said. “Another four miles and we reach East Wobsley Junction. Make it snappy and we shall just catch the up express, first stop London.”

William looked up into his face, and it seemed to James that he gave a brief nod of comprehension and approval. James turned. Through the trees to the east he could see the red roof of Honeysuckle Cottage, lurking like some evil dragon in ambush.

Then, together, man and dog passed silently into the sunset.

THAT is the story James Rodman told to me as the rain beat and rattled against the window-pane. As to whether it is true, that, of course, is an open question. I, personally, am of opinion that it is. There is no doubt that James did go to live at Honeysuckle Cottage three or four years ago, and, while there, underwent some experience which has left an ineradicable mark upon him. His eyes to-day have that unmistakable look which comes only to confirmed bachelors whose feet have been led to the very brink of the pit and who have gazed at close range into the naked face of matrimony.

And, if further proof is needed, there is William. He is now James’s inseparable companion. Would any man be habitually seen in public with a dog like William unless he had some solid cause to be grateful to him? I think not. Myself, when I observe William coming along the street, I cross the road and look into a shop-window till he has passed. I am not a snob, but I dare not risk my social prestige by being seen talking to him.

Nor is the precaution an unnecessary one. There is a shameless absence of all appreciation of class distinctions about William which recalls the worst excesses of the French Revolution. I have seen him with my own eyes chivvy a Pomeranian belonging to a duchess from near the Achilles statue to within a few yards of Queen’s Gate.

And yet James walks daily with him in Piccadilly. It is surely significant.

See the Saturday Evening Post appearance of this story for annotations.

Madame Eulalie’s Rare Plums

Madame Eulalie’s Rare Plums