THE unwonted gravity of Mr. Mulliner’s demeanour had struck us all directly he entered the bar parlour of the Angler’s Rest; and the silent, moody way in which he sipped his hot Scotch and lemon convinced us that something was wrong. We hastened to make sympathetic inquiries.

Our solicitude seemed to please him. He brightened a little.

“Well, gentlemen,” he said, “I had not intended to intrude my private troubles on this happy gathering, but, if you must know, a young second cousin of mine has left his wife and is filing papers of divorce. It has upset me very much.”

Miss Postlethwaite, our warm-hearted barmaid, who was polishing glasses, introduced a sort of bedside manner into her task.

“Some viper crept into his home?” she asked.

Mr. Mulliner shook his head.

“No,” he said, “no vipers. The whole trouble appears to have been that, whenever my second cousin spoke to his wife, she would open her eyes to their fullest extent, put her head on one side like a canary, and say ‘What?’ He said he had stood it for eleven months and three days, which he believes to be a record, and that the time had now come, in his opinion, to take steps.”

Mr. Mulliner sighed.

“The fact of the matter is,” he said, “marriage to-day is made much too simple for a man. He finds it so easy to go out and grab some sweet girl that when he has got her he does not value her. I am convinced that that is the real cause of this modern boom in divorce. What marriage needs, to make it a stable institution, is something in the nature of obstacles during the courtship period. I attribute the solid happiness of my nephew Osbert’s union, to take but one instance, to the events which preceded it. If the thing had been a walkover, he would have prized his wife far less highly.”

“It took him a long time to teach her his true worth?” we asked.

“Love burgeoned slowly?” hazarded Miss Postlethwaite.

“On the contrary,” said Mr. Mulliner, “she loved him at first sight. What made the wooing of Mabel Petherick-Soames so extraordinarily difficult for my nephew Osbert was not any coldness on her part, but the unfortunate mental attitude of J. Bashford Braddock. Does that name suggest anything to you, gentlemen?”

“No.”

“No.”

“You do not think that a man with such a name would be likely to be a toughish sort of egg?”

“He might be, now you mention it.”

“He was. In Central Africa, where he spent a good deal of his time exploring, ostriches would bury their heads in the sand at Bashford Braddock’s approach, and even rhinoceroses, the most ferocious beasts in existence, frequently edged behind trees and hid till he had passed. And the moment he came into Osbert’s life my nephew realized with a sickening clearness that those rhinoceroses had known their business.”

UNTIL the advent of this man Braddock (said Mr. Mulliner), Fortune seemed to have lavished her favours on my nephew Osbert in full and even overflowing measure. Handsome, like all the Mulliners, he possessed in addition to good looks the inestimable blessings of perfect health, a cheerful disposition, and so much money that Income-Tax assessors screamed with joy when forwarding Schedule D to his address. And, on top of all this, he had fallen deeply in love with a most charming girl and rather fancied that his passion was returned.

For several peaceful, happy weeks all went well. Osbert advanced without a set-back of any description through the various stages of calling, sending flowers, asking after her father’s lumbago, and patting her mother’s Pomeranian to the point where he was able, with the family’s full approval, to invite the girl out alone to dinner and a theatre. And it was on this night of nights, when all should have been joy and happiness, that the Braddock menace took shape.

Until Bashford Braddock made his appearance, no sort of hitch had occurred to mar the perfect tranquillity of the evening’s proceedings. The dinner had been excellent, the play entertaining. Twice during the third act Osbert had ventured to squeeze the girl’s hand in a warm, though of course gentlemanly, manner; and it seemed to him that the pressure had been returned. It is not surprising, therefore, that by the time they were saying good night on the steps of her house he had reached the conclusion that he was on to a good thing which should be pushed along.

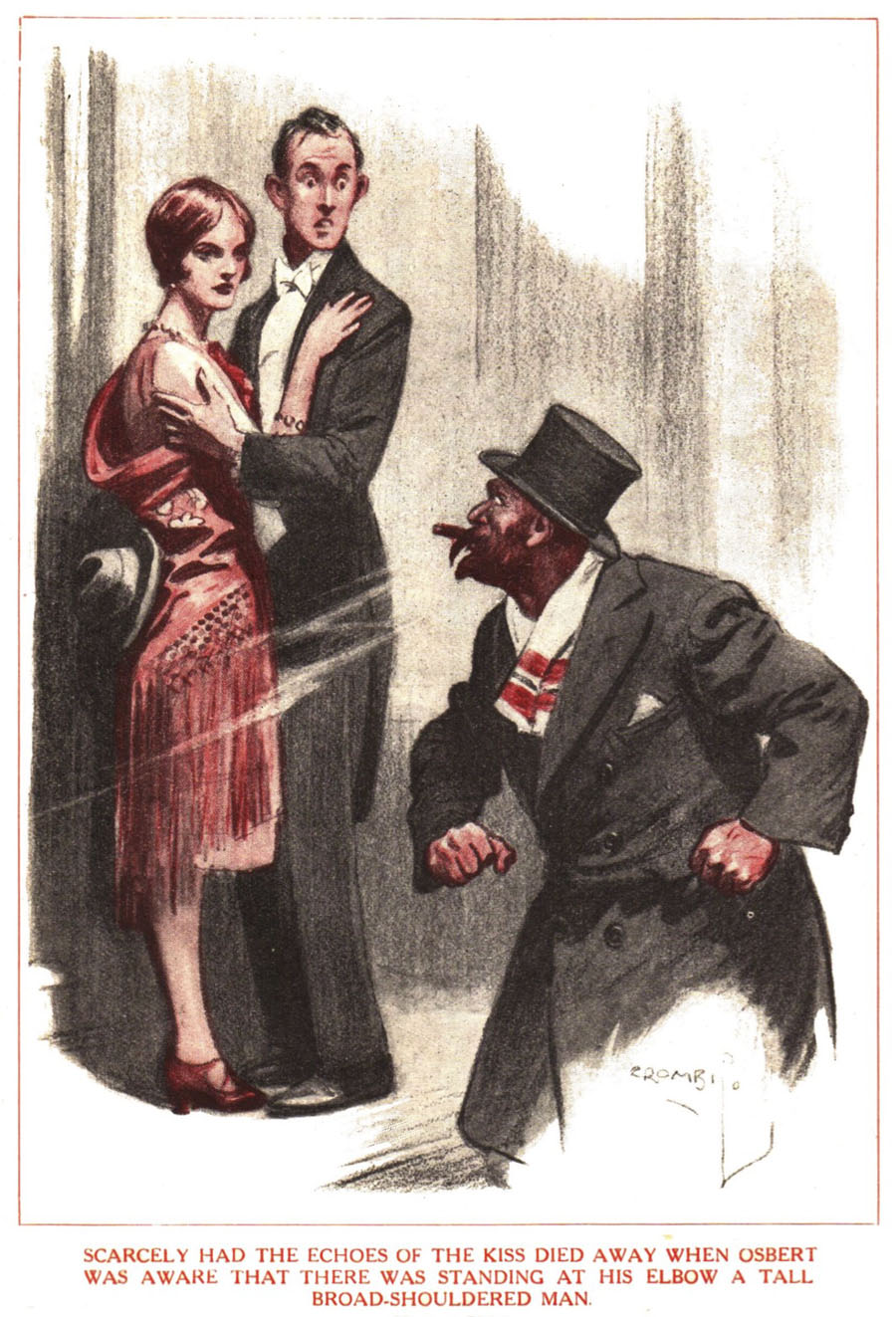

Putting his fortune to the test, to win or lose it all, Osbert Mulliner reached forward, clasped Mabel Petherick-Soames to his bosom, and gave her a kiss so ardent that in the silent night it sounded like somebody letting off a Mills bomb.

And scarcely had the echoes died away when he was aware that there was standing at his elbow a tall, broad-shouldered man in evening dress and an opera hat.

There was a pause.

“Hullo, Bashy!” said Mabel, and there was annoyance in her voice. “Where did you spring from? I thought you were exploring on the Congo or somewhere.”

The man removed his opera hat, squashed it flat, popped it out again, and spoke in a deep, rumbling voice.

“I returned from the Congo this morning. I have been dining with your father and mother. They informed me that you had gone to the theatre with this gentleman.”

“Mr. Mulliner. My cousin, Bashford Braddock,” said Mabel.

“How do you do?” said Osbert.

There was another pause. Bashford Braddock removed his opera hat, squashed it flat, popped it out again, and replaced it on his head. He seemed disappointed that he could not play a tune on it.

“Well, good night,” said Mabel.

“Good night,” said Osbert.

“Good night,” said Bashford Braddock. The door closed, and Osbert, looking from it to his companion, found that the other was staring at him with a peculiar expression in his eyes. They were hard, shiny eyes. Osbert did not like them.

“Mr. Mulliner,” said Bashford Braddock.

“Hullo?” said Osbert.

“A word with you, Mr. Mulliner. I saw all.”

“All?”

“All. Mr. Mulliner, you love that girl.”

“I do.”

“So do I.”

“You do?”

“I do.”

Osbert felt a little embarrassed. All he could think of to say was that it made them seem like one great big family.

“I have loved her since she was so high.”

“How high?” asked Osbert, for the light was uncertain.

“About so high. And I have always sworn that if ever any man came between us; if ever any slinking, sneaking, pop-eyed, lop-eared son of a sea-cook attempted to rob me of that girl, I would——”

“Er—what?” asked Osbert.

Bashford Braddock laughed a short, metallic laugh.

“Did you ever hear what I did to the King of Mgumbo-Mgumbo?”

“I didn’t even know there was a King of Mgumbo-Mgumbo.”

“There isn’t—now,” said Bashford Braddock.

Osbert was conscious of a clammy, creeping sensation in the region of his spine.

“What did you do to him?”

“Don’t ask.”

“But I want to know.”

“Far better not. You will find out quite soon enough, if you continue to hang round Mabel Petherick-Soames. That is all, Mr. Mulliner.” Bashford Braddock looked up at the twinkling stars. “What delightful weather we are having,” he said. “There was just the same quiet hush and peaceful starlight, I recollect, that time out in the Ngobi desert when I strangled the jaguar.”

Osbert’s Adam’s apple slipped a cog.

“W-what jaguar?”

“Oh, you wouldn’t know it. Just one of the jaguars out there. I had a rather tricky five minutes of it at first, because my right arm was in a sling and I could only use my left. Well, good night, Mr. Mulliner, good night.”

And Bashford Braddock, having removed his opera hat, squashed it flat, popped it out again, and replaced it on his head, stalked off into the darkness.

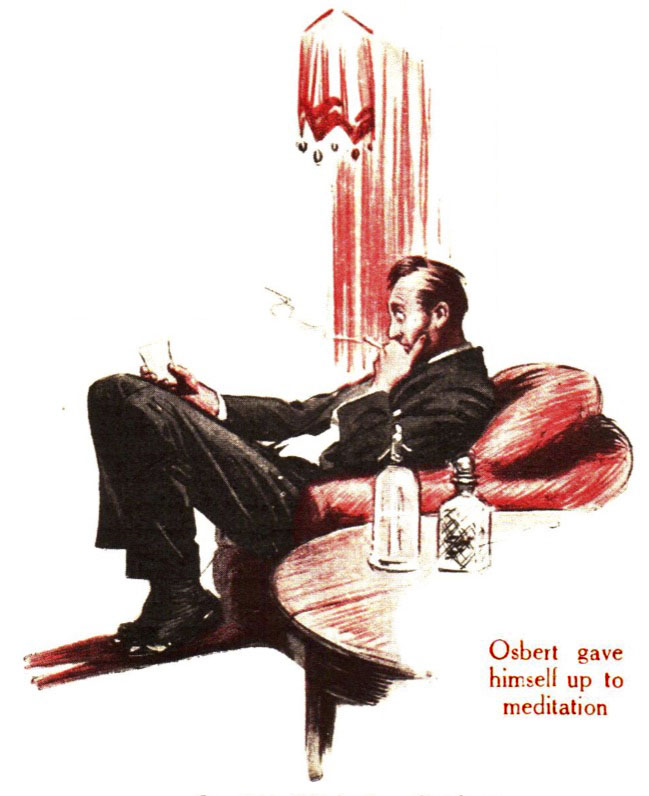

FOR several minutes after he had disappeared, Osbert Mulliner stood motionless, staring after him with unseeing eyes. Then, tottering round the corner, he made his way to his residence in South Audley Street and, contriving after three false starts to unlock the front door, climbed the stairs to his cosy library. There, having mixed himself a strong brandy-and-soda, he sat down and gave himself up to meditation; and eventually, after one quick drink and another taken rather slower, was able to marshal his thoughts with a certain measure of coherence. And those thoughts, I regret to say, when marshalled, were of a nature which I shrink from revealing to you.

FOR several minutes after he had disappeared, Osbert Mulliner stood motionless, staring after him with unseeing eyes. Then, tottering round the corner, he made his way to his residence in South Audley Street and, contriving after three false starts to unlock the front door, climbed the stairs to his cosy library. There, having mixed himself a strong brandy-and-soda, he sat down and gave himself up to meditation; and eventually, after one quick drink and another taken rather slower, was able to marshal his thoughts with a certain measure of coherence. And those thoughts, I regret to say, when marshalled, were of a nature which I shrink from revealing to you.

It is never pleasant, gentlemen, to have to display a relative in an unsympathetic light, but the truth is the truth and must be told. I am compelled, therefore, to confess that my nephew Osbert, forgetting that he was a Mulliner, writhed at this moment in an agony of craven fear.

It would be possible, of course, to find excuses for him. The thing had come upon him very suddenly, and even the stoutest are sometimes disconcerted by sudden peril. Then, again, his circumstances and upbringing had fitted him ill for such a crisis. A man who has been pampered by Fortune from birth becomes highly civilized; and the more highly civilized we are, the less adroitly do we cope with bounders of the Braddock type, who seem to belong to an earlier and rougher age. Osbert Mulliner was simply unequal to the task of tackling cave-men. Apart from some slight skill at contract bridge, the only thing he was really good at was collecting old jade; and what a help that would be, he felt as he mixed himself a third brandy-and-soda, in a personal combat with a man who appeared to think it only sporting to give jaguars a chance by fighting them one-handed.

He could see but one way out of the delicate situation in which he had been placed. To give Mabel Petherick-Soames up would break his heart, but it seemed to be a straight issue between that and his neck, and in this black hour the voting in favour of the neck was a positive landslide. Trembling in every limb, my nephew Osbert went to the desk and began to compose a letter of farewell.

He was sorry, he wrote, that he would be unable to see Miss Petherick-Soames on the morrow, as they had planned, owing to his unfortunately being called away to Australia. He added that he was pleased to have made her acquaintance, and that if, as seemed probable, they never saw each other again, he would always watch her future career with considerable interest.

Signing the letter “Yrs truly, O. Mulliner,” Osbert addressed the envelope and, taking it up the street to the post-office, dropped it in the box. Then he returned home and went to bed.

The telephone, ringing by his bedside, woke Osbert at an early hour next morning. He did not answer it. A glance at his watch had told him that the time was half-past eight, when the first delivery of letters is made in London. It seemed only too probable that Mabel, having just received and read his communication, was endeavouring to discuss the matter with him over the wire. He rose, bathed, shaved, and dressed, and had just finished a sombre breakfast when the door opened and Parker, his man, announced Major-General Sir Masterman Petherick-Soames.

An icy finger seemed to travel slowly down Osbert’s backbone. He cursed the preoccupation which had made him omit to instruct Parker to inform all callers that he was not at home. With some difficulty, for the bones seemed to have been removed from his legs, he rose to receive the tall, upright, grizzled, and formidable old man who entered. He had never met Mabel’s uncle Masterman, and he wished he was not meeting him now.

However, he rallied himself to play the host.

“Good morning,” he said. “Will you have a poached egg?”

“I will not,” replied Sir Masterman. “Poached egg, indeed! Poached egg, forsooth! Ha! Tchah! Bah!”

He spoke with such curt brusqueness that a stranger, had one been present, might have supposed him to belong to some league or society for the suppression of poached eggs. Osbert, however, with his special knowledge of the facts, was able to interpret this brusqueness correctly, and was not surprised when his visitor, gazing at him keenly with a pair of steely-blue eyes which must have got him very much disliked in military circles, plunged at once into the subject of the letter.

“Mr. Mulliner, my niece Mabel has received a strange communication from you.”

“Oh, she got it all right?” said Osbert, with an attempt at ease.

“It arrived this morning. You had omitted to stamp it. There was threepence to pay.”

“Oh, I say, I’m fearfully sorry. Careless of me. I must——”

Major-General Sir Masterman Petherick-Soames waved down his apologies.

“It is not the monetary loss which has so distressed my niece, but the letter’s contents. My niece is under the impression that last night she and you became engaged to be married, Mr. Mulliner.”

Osbert coughed.

“Well—er—not exactly. Not altogether. Not, as it were—I mean—you see——”

“I see very clearly. You have been trifling with my niece’s affections, Mr. Mulliner. I am very fond of all my nieces, and I have always sworn that if ever any man trifled with their affections I would——” He broke off and, taking a lump of sugar from the bowl, balanced it absently on the edge of a slice of toast. “Did you ever hear of a Captain Walkinshaw?”

“No.”

“Captain J. G. Walkinshaw? Dark man with an eyeglass. Used to play the saxophone.”

“No.”

“Ah! I thought you might have met him. He trifled with the affections of my niece Hester. I horsewhipped him on the steps of the Drones Club. Have you ever heard the name Blenkinsop-Bustard?”

“No.”

“Shortly after the affair of Captain Walkinshaw, Rupert Blenkinsop-Bustard trifled with the affections of my niece Gertrude. He was one of the Somersetshire Blenkinsop-Bustards. Wore a fair moustache and kept pigeons. I horsewhipped him on the steps of the Junior Bird-Fanciers. By the way, Mr. Mulliner, what is your club?”

“The United Jade-Collectors,” quavered Osbert.

“Has it steps?”

“I—I believe so.”

“Good. Good.” A dreamy look came into the General’s eyes. “Well, the announcement of your engagement to my niece Mabel will appear in to-morrow’s Morning Post. If it is contradicted—— Well, good morning, Mr. Mulliner, good morning.”

And, replacing in the dish the piece of bacon which he had been poising on a teaspoon, Major-General Sir Masterman Petherick-Soames left the room.

THE meditation to which my nephew Osbert had given himself up on the previous night was as nothing to the meditation to which he gave himself up now. For fully an hour he must have sat, his head supported by his hands, frowning despairingly at the remains of the marmalade on the plate before him. Though, like all the Mulliners, a clear thinker, he had to confess himself completely nonplussed. The situation had become so complicated that after awhile he went up to the library and tried to work it out on paper, letting x equal himself. But even this brought no solution, and he was still pondering deeply when Parker came up to announce lunch.

“Lunch?” said Osbert, amazed. “Is it lunch-time already?”

“Yes, sir. And might I be permitted to offer my respectful congratulations and good wishes, sir?”

“Eh?”

“On your engagement, sir. The General happened to mention to me as I let him out that a marriage had been arranged and would shortly take place between yourself and Miss Mabel Petherick-Soames. It was fortunate that he did so, as I was thus enabled to give the gentleman the information he required, when he rang up, straight—as you might say—from the horse’s mouth, sir.”

“Gentleman? What gentleman?”

“A Mr. Bashford Braddock, sir. He rang up about an hour after the General had left and said he had been informed of your engagement and wished to know if the news was well-founded. I assured him that it was and he said he would be calling to see you later. He was very anxious to know when you would be at home. He seemed a nice, friendly gentleman, sir.”

Osbert rose as if the chair in which he sat had suddenly become incandescent.

“Parker!”

“Sir?”

“I am unexpectedly obliged to leave London, Parker. I don’t know where I am going—probably the Zambesi or Greenland—but I shall be away a long time. I shall close the house and give the staff an indefinite holiday. They will receive three months’ wages in advance, and at the end of that period will communicate with my lawyers, Messrs. Peabody, Thrupp, Thrupp, Thrupp, Thrupp, and Peabody, of Lincoln’s Inn. Inform them of this.”

“Very good, sir.”

“And, Parker.”

“Sir?”

“I am thinking of appearing shortly in some amateur theatricals. Kindly step round the corner and get me a false wig, a false nose, some false whiskers, and a good stout pair of blue spectacles.”

OSBERT’S plans when, after a cautious glance up and down the street, he left the house an hour later and directed a taxi-cab to take him to an obscure hotel in the wildest and least-known part of the Cromwell Road were of the vaguest. It was only when he reached that haven and had thoroughly wigged, nosed, whiskered, and blue-spectacled himself that he began to formulate a definite plan of campaign. He spent the rest of the day in his room, and shortly before lunch next morning set out for the second-hand clothing establishment of the brothers Cohen near Covent Garden to purchase a complete traveller’s outfit. It was his intention to board the boat sailing on the morrow for India and to potter awhile about the world, taking in en route Japan, South Africa, Peru, Mexico, China, Venezuela, the Fiji Islands, and other beauty-spots.

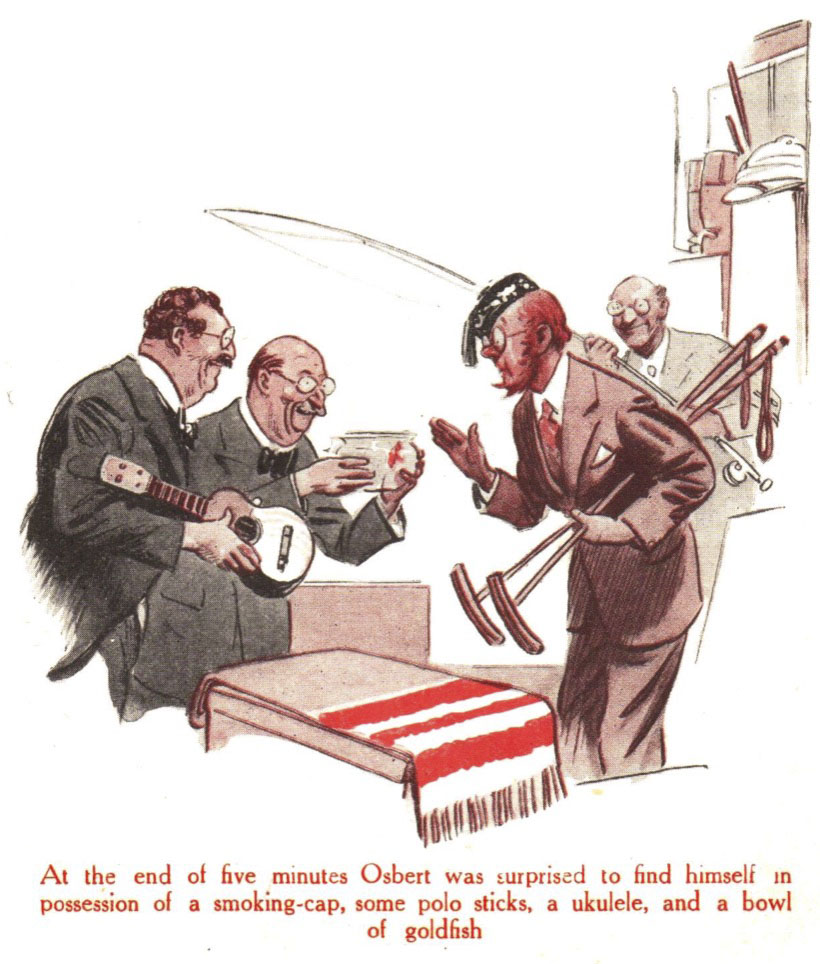

All the Cohens seemed glad to see him when he arrived at the shop. They clustered about him in a body, as if guessing by instinct that here came one of those big orders. At this excellent emporium one may buy, in addition to second-hand clothing, practically anything that exists; and the difficulty—for the brothers are all thrustful salesmen—is to avoid doing so. At the end of five minutes Osbert was surprised to find himself in possession of a smoking-cap, three boxes of poker chips, some polo sticks, a fishing-rod, a concertina, a ukulele, and a bowl of goldfish.

He was annoyed. These men appeared to him to have got quite a wrong angle on the situation. They seemed to think that he proposed to make his travels one long round of pleasure. As clearly as he was able, he tried to tell them that in the few broken years that remained to him before a shark or jungle-fever put an end to his sorrows he would have little heart for polo, for poker, or for playing the concertina while watching the gambols of goldfish. They might just as well offer him, he said querulously, a cocked hat or a sewing-machine.

Instant activity prevailed among the brothers.

“Fetch the gentleman his sewing-machine, Isador.”

“And, while you’re getting him the cocked hat, Lou,” said Irving, “ask the gentleman in the shoe department if he’ll be kind enough to step this way. You’re in luck,” he assured Osbert. “If you’re going travelling in foreign parts, he’s the very gentleman to advise you. You’ve heard of Mr. Braddock?”

There was very little of Osbert’s face visible behind his whiskers, but that little paled beneath its tan.

“Mr. B-Braddock?”

“That’s right. Mr. Braddock, the explorer.”

“Air!” said Osbert. “Give me air!”

He made rapidly for the door, and was about to charge through when it opened to admit a tall, distinguished-looking man of military appearance.

“Shop!” cried the new-comer in a clear, patrician voice, and Osbert reeled back against a pile of trousers. It was Major-General Sir Masterman Petherick-Soames.

A platoon of Cohens advanced upon him, Isador hastily snatching up a fireman’s helmet and Irving a microscope and a couple of jig-saw puzzles. The General waved them aside.

“Do you,” he asked, “keep horsewhips?”

“Yes, sir. Plenty of horsewhips.”

“I want a nice strong one with a medium-sized handle and lots of spring,” said Major-General Sir Masterman Petherick-Soames.

And at this moment Lou returned, followed by Bashford Braddock.

“Is this the gentleman?” said Bashford Braddock genially. “You’re going abroad, sir, I understand. Delighted if I can be of any service.”

“Bless my soul,” said Major-General Sir Masterman Petherick-Soames. “Bashford? It’s so confoundedly dark in here, I didn’t recognize you.”

“Switch on the light, Irving,” said Isador.

“No, don’t,” said Osbert. “My eyes are weak.”

“If your eyes are weak, you ought not to be going to the tropics,” said Bashford Braddock.

“This gentleman a friend of yours?” asked the General.

“Oh, no. I’m just going to help him buy an outfit.”

“The gentleman’s already got a smoking-cap, poker chips, polo sticks, a fishing-rod, a concertina, a ukulele, a bowl of goldfish, a cocked hat, and a sewing-machine,” said Isador.

“Ah!” said Bashford Braddock. “Then all he will require now is a sun helmet, a pair of puttees, and some ointment for alligator bites.”

With the rapid decision of an explorer who is buying things for which somebody else is going to pay, he completed the selection of Osbert’s outfit.

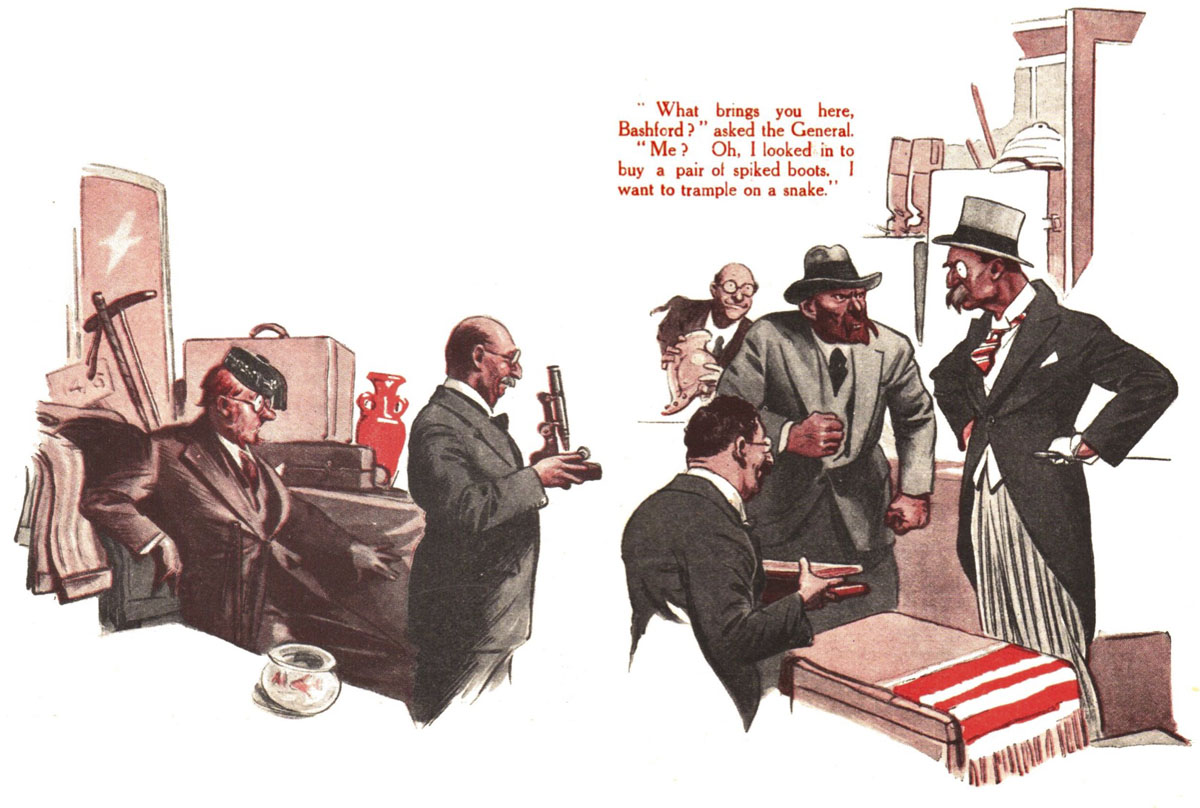

“And what brings you here, Bashford?” asked the General.

“Me? Oh, I looked in to buy a pair of spiked boots. I want to trample on a snake.”

“An odd coincidence. I came here to buy a horsewhip to horsewhip a snake.”

“A bad week-end for snakes,” said Bashford Braddock.

The General nodded gravely.

“Of course, my snake,” he said, “may prove not to be a snake. In classifying him as a snake I may have misjudged him. In that case I shall not require this horsewhip. Still, they’re always useful to have about the house.”

“Undoubtedly. Lunch with me, General?”

“Delighted, my dear fellow.”

“Good-bye, sir,” said Bashford Braddock, giving Osbert a friendly nod. “Glad I was able to be of some use. When do you sail?”

“Gentleman’s sailing to-morrow morning on the Rajputana,” said Isador.

“What!” cried Major-General Sir Masterman Petherick-Soames. “Bless my soul! I didn’t realize you were going to India. I was out there for years and can give you all sorts of useful hints. The old Rajputana? Why, I know the purser well. I’ll come and see you off and have a chat with him. No doubt I shall be able to get you a number of little extra attentions. No, no, my dear fellow, don’t thank me. I have a good deal on my mind at the moment, and it will be a relief to do somebody a kindness.”

IT seemed to Osbert, as he crawled back to the shelter of his Cromwell Road bedroom, that Fate was being altogether too rough with him. Obviously, if Sir Masterman Petherick-Soames intended to come down to the boat to see him off, it would be madness to attempt to sail. On the deck of a liner under the noonday sun the General must inevitably penetrate his disguise. His whole scheme of escape must be cancelled and another substituted. Osbert ordered two pots of black coffee, tied a wet handkerchief round his forehead, and plunged once more into thought.

It has been frequently said of the Mulliners that you may perplex but you cannot baffle them. It was getting on for dinner-time before Osbert finally decided upon a plan of action; but this plan, he perceived as he examined it, was far superior to the first one.

He had been wrong, he saw, in thinking of flying to foreign climes. For one who desired as fervently as he did never to see Major-General Sir Masterman Petherick- Soames again in this world, the only real refuge was a London suburb. Any momentary whim might lead Sir Masterman to pack a suit-case and take the next boat to the Far East, but nothing would ever cause him to take a tram for Dulwich, Cricklewood, Winchmore Hill, Brixton, Balham, or Surbiton. In those trackless wastes Osbert would be safe.

Osbert decided to wait till late at night; then go back to his house in South Audley Street, pack his collection of old jade and a few other necessaries, and vanish into the unknown.

It was getting on for midnight when, creeping warily to the familiar steps, he inserted his latchkey in the familiar keyhole. He had feared that Bashford Braddock might be watching the house, but there were no signs of him. He slipped swiftly into the dark hall and closed the front door softly behind him.

It was at this moment that he became aware that from under the door of the dining-room at the other end of the hall there was stealing a thin stream of light.

For an instant this evidence that the house was not, as he had supposed, unoccupied startled Osbert considerably. Then, recovering himself, he understood what must have happened. Parker, his man, instead of leaving as he had been told to do, was taking advantage of his employer’s presumed absence from London to stay on and do some entertaining. Osbert, thoroughly incensed, hurried to the dining-room and felt that his suspicion had been confirmed. On the table were set out all the materials, except food and drink, of a cosy little supper for two. The absence of food and drink was accounted for, no doubt, by the fact that Parker and—Osbert saw only too good reason to fear—his lady-friend were down in the larder, fetching them.

Osbert boiled from his false wig to the soles of his feet with a passionate fury. So this was the sort of thing that went on the moment his back was turned, was it? There were heavy curtains hiding the window, and behind these he crept. It was his intention to permit the feast to begin and then, stepping forth like some avenging Nemesis, to confront his erring man-servant and put it across him in no uncertain manner. Bashford Braddock and Major-General Sir Masterman Petherick-Soames, with their towering stature and whipcord muscles, might intimidate him, but with a shrimp like Parker he felt that he could do himself justice. Osbert had been through much in the last forty-eight hours, and unpleasantness with a man who, like Parker, stood a mere five feet five in his socks appeared to him rather in the nature of a tonic.

HE had not been waiting long when there came to his ears the sound of footsteps outside. He softly removed his wig, his nose, his whiskers, and his blue spectacles. There must be no disguise to soften the shock when Parker found himself confronted. Then, peeping through the curtains, he prepared to spring.

Osbert did not spring. Instead, he shrank back like a more than ordinarily diffident tortoise into its shell, and tried to achieve the maximum of silence by breathing through his ears. For it was no Parker who had entered, no frivolous lady-friend, but a couple of plug-uglies of such outstanding physique that Bashford Braddock might have been the little brother of either of them.

Osbert stood petrified. He had never seen a burglar before, and he wished, now that he was seeing these, that it could have been arranged for him to do so through a telescope. At this close range they gave him much the same feeling the prophet Daniel must have had on entering the lions’ den, before his relations with the animals had been established on their subsequent basis of easy camaraderie. He was thankful that, when the breath which he had been holding for some eighty seconds at length forced itself out in a loud gasp, the noise was drowned by the popping of a cork.

It was from a bottle of Osbert’s best Bollinger that this cork had been removed. The marauders, he was able to see, were men who believed in doing themselves well. In these days, when almost everybody is on some sort of diet, it is rarely that one comes across the old-fashioned type of diner who does not worry about balanced meals and calories, but just squares his shoulders and goes at it till his eyes bubble. Osbert’s two guests plainly belonged to this nearly obsolete species. They were drinking out of tankards and eating three varieties of meat simultaneously, as if no such thing as a high blood-pressure had ever been invented. A second pop announced the opening of another quart of champagne.

At the outset of the proceedings there had been little or nothing in the way of supper-table conversation. But now, the first keen edge of his appetite satisfied by about three pounds of ham, beef, and mutton, the burglar who sat nearest to Osbert was able to relax. He looked about him approvingly.

“Nice little crib, this, Ernest,” he said.

“R!” replied his companion—a man of few words, and those rather hampered by cold potatoes and bread.

“Must have been some real swells in here one time and another.”

“R!”

“Baronets and such, I wouldn’t be surprised.”

“R!” said the second burglar, helping himself to more champagne and mixing in a little port, sherry, Italian vermouth, old brandy, and green Chartreuse to give it body.

The first burglar looked thoughtful.

“Talking of baronets,” he said, “a thing I’ve often wondered is—well, suppose you’re having a dinner, see?”

“R!”

“As it might be in this very room.”

“R!”

“Well, would a baronet’s sister go in before the daughter of the younger son of a peer? I’ve often wondered about that.”

The second burglar finished his champagne, port, sherry, Italian vermouth, old brandy, and green Chartreuse, and mixed himself another.

“Go in?”

“Go in to dinner.”

“If she was quicker on her feet, she would.”

“What do you mean?”

“Why, she’d get to the door first. Stands to reason.”

The first burglar raised his eyebrows.

“Ernest,” he said coldly, “you talk like an uneducated son of a what-not. Haven’t you never been taught nothing about the rules and manners of good society?”

The second burglar flushed. It was plain that the rebuke had touched a tender spot. There was a strained silence. The first burglar resumed his meal. The second burglar watched him with a hostile eye. He had the air of a man who is waiting for his chance, and it was not long before he found it.

“Harold,” he said.

“Well?” said the first burglar.

“Don’t gollup your food, Harold,” said the second burglar.

The first burglar started. His eyes gleamed with sudden fury. His armour, like his companion’s, had been pierced.

“Who’s golluping his food?”

“You are.”

“I am?”

“Yes, you.”

“Who, me?”

“R!”

“Golluping my food?”

“R! Like a pig or something.”

It was evident to Osbert, peeping warily through the curtains, that the generous fluids which these two men had been drinking so lavishly had begun to have their effect. They spoke thickly, and their eyes had become red and swollen.

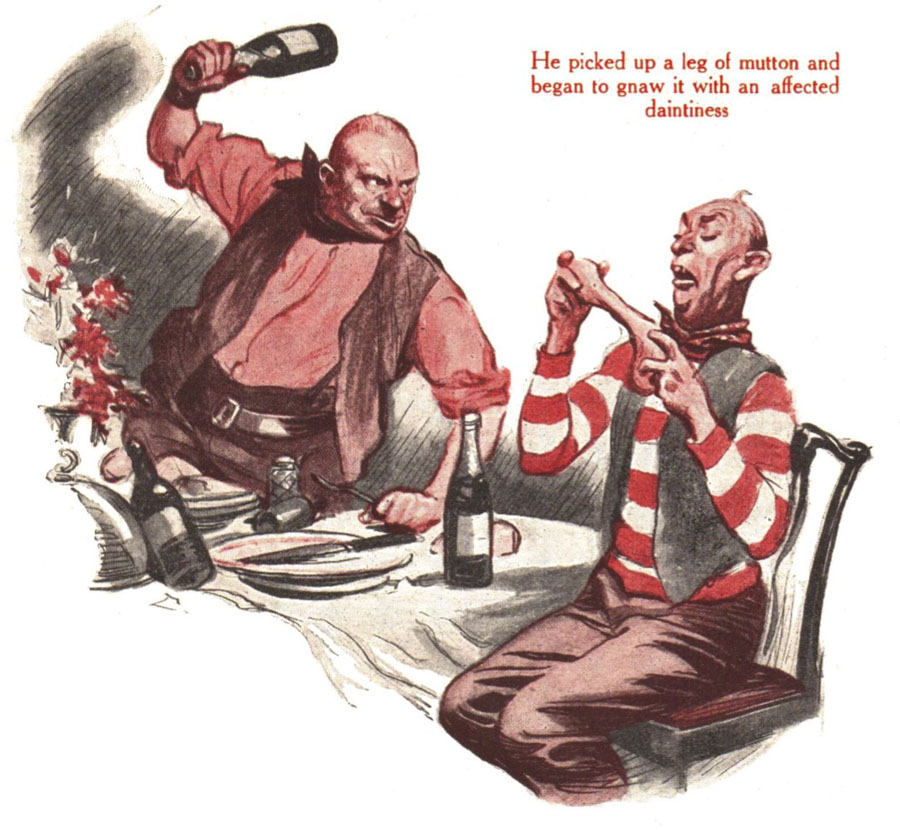

“I may not know all about baronets’ younger sisters,” said the burglar Ernest, “but I don’t gollup my food like pigs or something.”

And, as if to drive home the reproach, he picked up the leg of mutton and began to gnaw it with an affected daintiness.

The next moment the battle had been joined. The spectacle of the other’s priggish object-lesson was too much for the burglar Harold. He plainly resented tuition in the amenities from one on whom he had always looked as a social inferior. With a swift movement of the hand he grasped the bottle before him and bounced it smartly on his colleague’s head.

Osbert Mulliner cowered behind the curtain. The sportsman in him whispered that he was missing something good, for ring-seats to view which many men would have paid large sums, but he could not nerve himself to look out. However, there was plenty of interest in the thing, even if you merely listened. The bumps and crashes seemed to indicate that the two principals were hitting one another with virtually everything in the room except the wallpaper and the large sideboard. Now they appeared to be grappling on the floor, anon fighting at long range with bottles. Words and combinations of words, of whose existence he had till then been unaware, floated to Osbert’s ears; and more and more he asked himself, as the combat proceeded, What would the harvest be?

And then, with one titanic crash, the battle ceased as suddenly as it had begun.

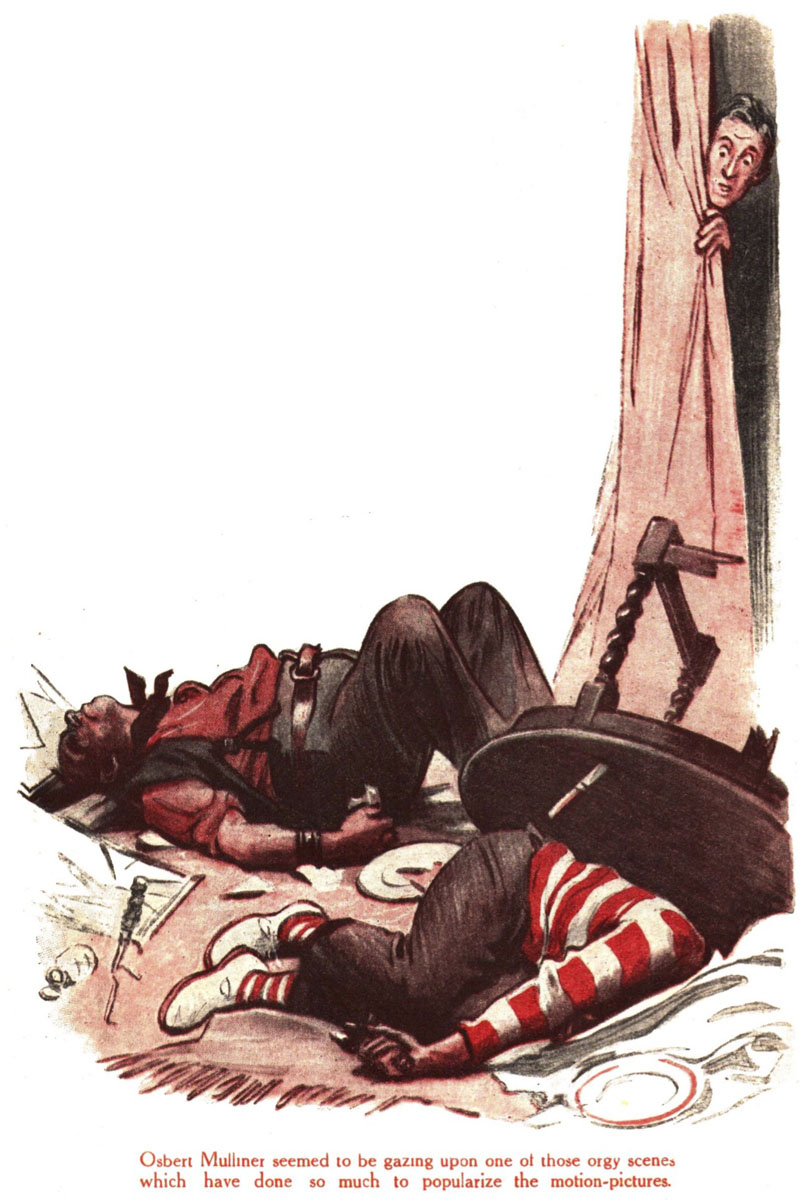

IT was some moments before Osbert Mulliner could bring himself to peep from behind the curtains. When he did so, he seemed to be gazing upon one of those orgy scenes which have done so much to popularize the motion-pictures. Scenically, the thing was perfect. All that was needed to complete the resemblance was a few attractive-looking girls with hardly any clothes on.

IT was some moments before Osbert Mulliner could bring himself to peep from behind the curtains. When he did so, he seemed to be gazing upon one of those orgy scenes which have done so much to popularize the motion-pictures. Scenically, the thing was perfect. All that was needed to complete the resemblance was a few attractive-looking girls with hardly any clothes on.

He came out and gaped down at the ruins. The burglar Harold was lying with his head in the fireplace; the burglar Ernest was doubled up under the table; and it seemed to Osbert almost absurd to think that these were the same hearty fellows who had come into the room to take pot-luck so short a while before. Harold had the appearance of a man who has been passed through a wringer. Ernest gave the illusion of having recently become entangled in some powerful machinery. If, as was probable, they were known to the police, it would take a singularly keen-eyed constable to recognize them now.

The thought of the police reminded Osbert of his duty as a citizen. He went to the telephone and called up the nearest station and was informed that representatives of the Law would be round immediately to scoop up the remains. He went back to the dining-room to wait, but its atmosphere jarred upon him. He felt the need of fresh air; and, going to the front door, he opened it and stood upon the steps, breathing deeply.

And, as he stood there, a form loomed through the darkness and a heavy hand fell on his arm.

“Mr. Mulliner, I think? Good evening, Mr. Mulliner,” said the voice of Bashford Braddock. “A word with you, Mr. Mulliner.”

Osbert returned his gaze without flinching. He was conscious of a strange, almost uncanny calm. The fact was that, everything in this world being relative, he was regarding Bashford Braddock at this moment as rather an undersized little squirt and wondering why he had ever worried about the man. To one who had come so recently from the society of Harold and Ernest, Bashford Braddock seemed like one of Singer’s Midgets.

“Ah, Braddock?” said Osbert.

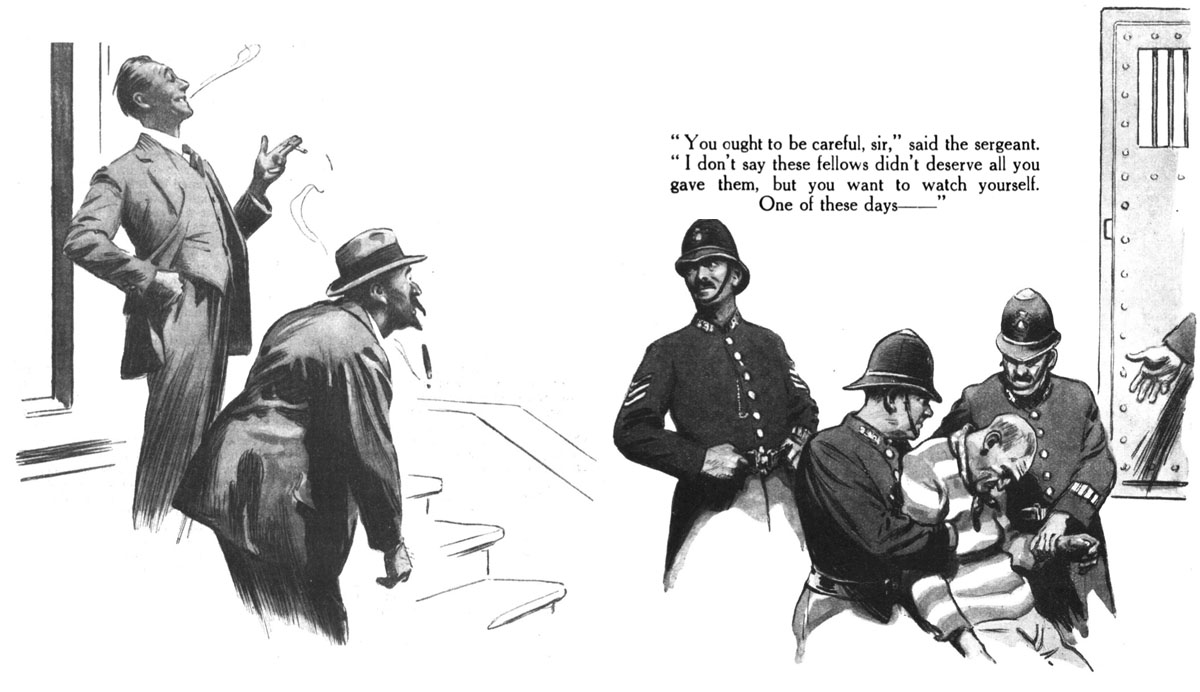

AT this moment, with a grinding of brakes, a van stopped before the door and policemen began to emerge.

“Mr. Mulliner?” asked the sergeant.

Osbert greeted him affably.

“Come in,” he said. “Come in. Go straight through. You will find them in the dining-room. I’m afraid I had to handle them a little roughly. You had better ’phone for a doctor.”

“Bad, are they?”

“A little the worse for wear.”

“Well, they asked for it,” said the sergeant.

“Exactly,” said Osbert.

Bashford Braddock had been standing listening to this exchange of remarks with a somewhat perplexed air.

“What’s all this?” he said.

Osbert came out of his thoughts with a start.

“You still here, my dear chap?”

“I am.”

“Want to see me about anything? Something on your mind?”

“I just want a quiet five minutes alone with you, Mr. Mulliner.”

“Certainly,” said Osbert. “Certainly, certainly, certainly. Just wait till these policemen have gone and I will be at your disposal. We have had a little burglary.”

“Burg——” Bashford Braddock was beginning, when there came out on to the steps a couple of policemen. They were supporting the burglar Harold, and were followed by others assisting the burglar Ernest. The sergeant, coming last, shook his head at Osbert a little gravely.

“You ought to be careful, sir,” he said. “I don’t say these fellows didn’t deserve all you gave them, but you want to watch yourself. One of these days——”

“Perhaps I did overdo it a little,” admitted Osbert. “But I am rather apt to see red on these occasions. Well, good night, sergeant, good night. And now,” he said, taking Bashford Braddock’s arm in a genial grip, “what was it you wanted to talk to me about? Come into the house. Wo shall be all alone there. I gave the staff a holiday. There won’t be a soul except ourselves.”

Bashford Braddock released his arm. He seemed embarrassed. His face, as the light of the street lamp shone upon it, was strangely pale.

“Did you——” He gulped a little. “Was that really you?”

“Really me? Oh, you mean those two fellows? Oh, yes, I found them in my dining-room, eating my food and drinking my wine as cool as you please, and naturally I set about them. But the sergeant was quite right. I do get too rough when I lose my temper. I must remember,” he said, taking out his handkerchief and tying a knot in it, “to cure myself of that. The fact is, I sometimes don’t know my own strength. But you haven’t told me what it is you want to see me about.”

Bashford Braddock swallowed twice in quick succession. He edged past Osbert to the foot of the steps.

“Oh, nothing, nothing.”

“But, my dear fellow,” protested Osbert, “it must have been something important to bring you round at this time of night.”

Bashford Braddock coughed.

“Well, it was like this. I—er—saw the announcement of your engagement in the paper this morning, and I thought—I—er—just thought I would pop round and ask you what you would like for a wedding present.”

“My dear chap! Much too kind of you.”

“So—er—so silly if I gave a fish-slice and found that everybody else had given fish-slices.”

“That’s true. Well, why not come inside and talk it over?”

“No, I won’t come in, thanks. Perhaps you will write and let me know. Poste Restante, Bongo on the Congo, will find me. I am returning there immediately.”

“Certainly,” said Osbert. He looked down at his companion’s feet. “My dear chap, what on earth are you wearing those extraordinary boots for?”

“Corns,” said Bashford Braddock.

“Why the spikes?”

“They relieve the pressure on the feet.”

“I see. Well, good night, Mr. Braddock.”

“Good night, Mr. Mulliner.”

“Good night,” said Osbert.

“Good night,” said Bashford Braddock.

Annotations to this story as it appeared in book form are in the notes to Mr. Mulliner Speaking on this site.

Madame Eulalie’s Rare Plums

Madame Eulalie’s Rare Plums