Politicians

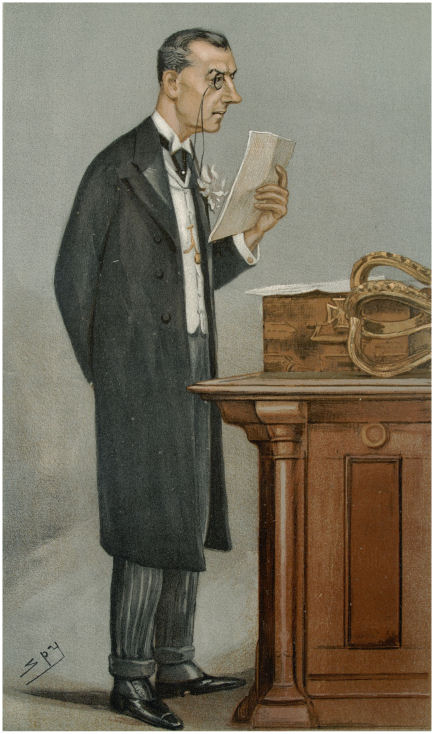

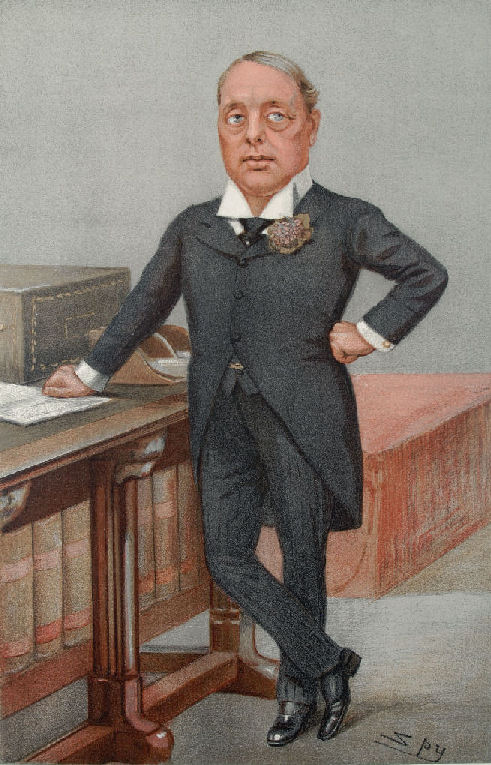

Joseph Chamberlain

“The Colonies”: a caricature of Joseph Chamberlain by Leslie Matthew Ward (‘Spy’), from Vanity Fair, 7 March 1901.

Chamberlain (1836-1914) was a charismatic orator and radical politician. From May 1876 until his death, in July 1914, he was member of parliament for Birmingham (Birmingham West from 1885). Before entering parliament, Chamberlain had been a successful businessman in Birmingham and, between November 1873 and May 1876, was the city’s mayor; Birmingham and the West Midlands remained his power base throughout his political career. Elected to parliament as a Liberal, Chamberlain served as President of the Board of Trade in Gladstone’s second ministry, from 1880-1885. In early 1886, he served briefly in Gladstone’s third ministry, but resigned over Gladstone’s proposals for Irish Home Rule and left the Liberal party to join a new Liberal Unionist Association, which formed a loose alliance with the Conservatives. In 1895, Henry Campbell-Bannerman’s Liberal government resigned and Lord Salisbury formed a coalition government, in which the Liberal Unionists were offered four Cabinet posts: Chamberlain rejected the Treasury and Home Office in favour of the Colonial Office, a less prestigious appointment, but one that he believed offered more scope for his ambitions. He served as Colonial Secretary continuously until September 1903, when he resigned from the Cabinet over the issue of tariff reform. It was while serving as Colonial Secretary that Chamberlain became convinced of the need for a scheme of Imperial Preference, a view that put him at odds with many of the most powerful politicians of his day.

In April 1902, the Chancellor of the Exchequer, Sir Michael Hicks Beach, imposed a small tariff on imported corn. Chamberlain saw this as an opportunity to start a reform of Britain’s trade laws. Hicks Beach resigned in July 1902, on the resignation of Lord Salisbury as Prime Minister, and Salisbury’s successor, his nephew Arthur Balfour, appointed a free-trader, C T Ritchie, as Chancellor. Despite Ritchie’s opposition, Chamberlain persuaded the Cabinet, in November 1902, to retain the corn tax in the next budget, but to remit it in favour of the colonies. He then left for an official tour of South Africa, where the Boer War had recently ended, but while he was away Ritchie succeeded in persuading the Cabinet to reverse its earlier decision. Chamberlain returned to find that he no longer had the support of the Cabinet and in the budget presented to Parliament in April 1903 the corn tax was abolished altogether.

In mid-May, in his Birmingham constituency, Chamberlain launched a strong appeal for imperial preference. Two weeks later, he repeated his view in the House of Commons, where he received support from many of the Liberal Unionists. The Prime Minister, Balfour, trying to balance the opposing views within his coalition government, refused to commit himself to one side or the other but, in an effort to retain Chamberlain in his Cabinet, produced a pamphlet in which he outlined some reforming measures. These did not go far enough for Chamberlain who, in September 1903, submitted his resignation.

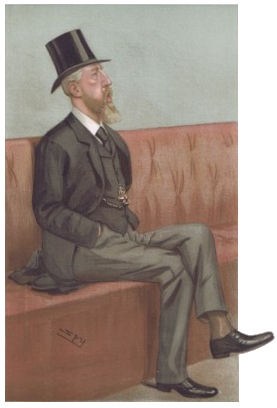

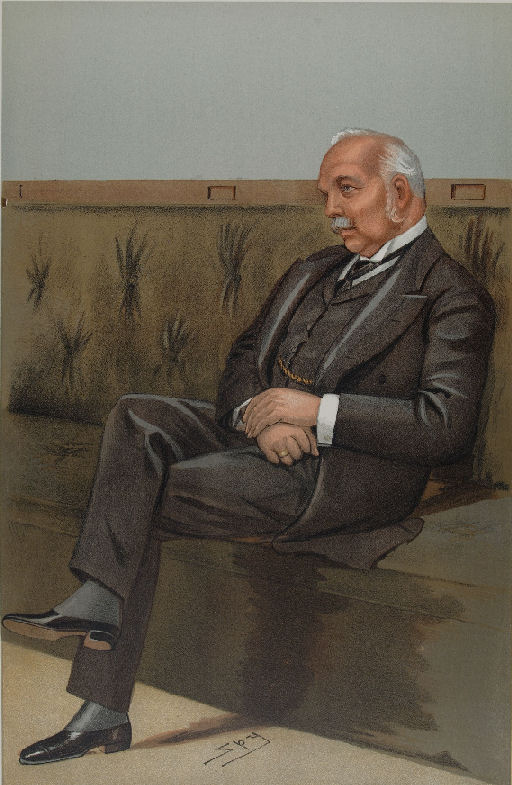

The Duke of Devonshire

“Education and Defence”: a caricature of Spencer Compton Cavendish, 8th Duke of Devonshire, by Leslie Matthew Ward (‘Spy’), from Vanity Fair,

15 May 1902.

Spencer Cavendish, 8th Duke of Devonshire (1833-1908), known until 1891 by the courtesy title of Marquess of Hartington, was one of the leading politicians of his era: he led the Liberal Party from 1875 to 1880, was leader of the Liberal Unionists from 1886 to 1903, and led the Conservative-Unionists in the House of Lords in 1902-03. He also, on three occasions, refused invitations to become Prime Minister, not for lack of ambition but because on each occasion he judged the circumstances not to be propitious.

Like Chamberlain, Devonshire was a fervent opponent of Irish Home Rule—his younger brother, Frederick, was murdered by Irish nationalists in 1882—but that was almost all they had in common: Devonshire was one of the old Whig aristocracy, while Chamberlain was a self-made man and a radical; Devonshire was, by inclination, a free trader and became an outspoken critic of Chamberlain’s views.

When Chamberlain tendered his resignation, in September 1903, the Prime Minister, Arthur Balfour, manoeuvred three free traders into resigning from the Cabinet—C T Ritchie, Chancellor of the Exchequer; Lord George Hamilton, Secretary for India; and Lord Balfour of Burleigh, Secretary for Scotland,—but hoped that Devonshire would agree to stay. Devonshire did indeed remain in the government for a few weeks, but then, to Balfour’s surprise, tendered his resignation also.

Within a few weeks, Devonshire had become president of the Unionist Free Food League and, before the end of the year, was advising Liberal Unionists not to vote for Unionist candidates who supported Chamberlain’s tariff reform proposals. In the spring of 1904, he finally resigned from the Liberal Unionist party in protest at Chamberlain’s plans.

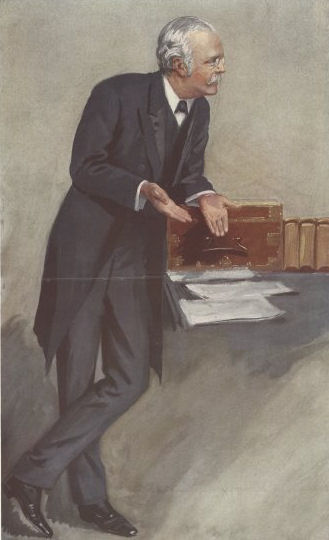

Arthur Balfour

“Dialectics”: a caricature of Rt Hon Arthur Balfour by XIT, from Vanity Fair,

27 January 1910.

Balfour (1848-1930) was a Conservative politician and Prime Minister from July 1902 to December 1905. He served under his uncle, Lord Salisbury, as Secretary for Ireland and then as Leader of the House of Commons, before succeeding Salisbury as Prime Minister upon the latter’s resignation. Balfour was—like Chamberlain— firmly opposed to Irish Home Rule, but had a more ambivalent attitude to tariff reform; he described himself as a free-trader, but not of the dogmatic variety, and while not favouring imperial preference he was prepared to consider proposals for retaliatory tariffs. As Prime Minister he faced the difficult task of trying to achieve a compromise between the two opposing factions in his coalition, a task which ultimately proved impossible: in December 1905 he resigned as Prime Minister, hoping that a minority Liberal government, under Henry Campbell-Bannerman, would prove unworkable; Campbell-Bannerman, however, immediately called a general election for January 1906, when the Liberals gained a landslide victory.

Following Chamberlain’s speech of 15 May 1903, Balfour worked hard to hold his government together. He refused to allow the issue of fiscal reform to be debated in the House of Commons, except in the context of an opposition vote of no confidence—and the Liberals did not feel strong enough to force such a vote—but he could not stop constant sniping by both the oppposition and the more maverick members of his own party, such as Winston Churchill; nor could he control matters in the House of Lords, where the Duke of Devonshire was the leading representative of the government.

When, in early September 1903, Chamberlain announced his intention to resign, Balfour kept this information from the rest of the Cabinet. Having decided that, if he had to lose Chamberlain, it would be better for government unity if the leading free traders were to go also, he manoeuvred two of them—C T Ritchie and Lord George Hamilton—into submitting their resignations. Two other Cabinet ministers, Devonshire and Lord Balfour of Burleigh, together with a junior Treasury minister, the Hon Arthur Elliott, also submitted their resignations. Balfour persuaded Devonshire to withdraw his resignation, but two weeks later Devonshire submitted his resignation again, giving it as his reason that a recent speech by Balfour had caused him to decide that he could no longer support the government.

Lord Rosebery

“Little Bo-Peep”: a caricature of Lord Rosebery by Leslie Matthew Ward (‘Spy’), from Vanity Fair,

14 March 1901.

Archibald Primrose, 5th Earl of Rosebery (1847-1929), was a Liberal politician and British Prime Minister. His father, also Archibald, was heir to the earldom and was known by the courtesy title of Lord Dalmeny until his death, in 1851, when the courtesy title passed to his son. The 4th earl died in 1868, and his grandson succeeded him as the 5th Earl.

Rosebery was recruited into the Liberal party by Gladstone, under whom he served as Foreign Secretary, during Gladstone’s short-lived third ministry, in 1886, and again in Gladstone’s fourth ministry, from 1892-94; while out of office, he served, from 1889, as the first chairman of the newly-created London County Council. A firm believer in imperialism and a strong navy, Rosebery became the leader of an imperialist faction within the party. When Gladstone retired, in March 1894, it was Rosebery whom Queen Victoria invited to form a government, ignoring the claims of other possible candidates, among them Gladstone’s Chancellor of the Exchequer, Sir William Harcourt, who became the party’s leader in the House of Commons. Harcourt, who belonged to a more radical wing of the party, was critical of many of Rosebery’s policies and this led to friction within the Cabinet. Rosebery, tired by the continual dissension, lost interest in the business of running a government and when, in June 1895, the Government lost a vote on Army supply by the small margin of seven votes Rosebery chose to submit his resignation to the Queen. At the ensuing general election, in July 1895, the Conservatives, under Lord Salisbury, won the largest number of seats and, in an alliance with the Liberal Unionists, formed a coalition government that lasted until December 1905.

After resigning as Prime Minister, Rosebery became increasingly disenchanted with the Liberal party. He remained the party’s leader only until October 1896, when he resigned and was succeeded by Harcourt. His support for the Boer War and opposition to Irish Home Role distanced him from mainstream Liberal opinion. He eventually left the Liberal party and moved to the cross-benches in the House of Lords from where, in his later years, he became a strong critic of the Liberal governments of Campbell-Bannerman and Asquith.

Outside of politics, Rosebery had a passionate interest in breeding racehorses and three of his horses won the Derby, one of Britain’s most prestigious races, which takes place annually at Epsom racecourse, close to where Rosebery had one of his homes, The Durdans. Rosebery had stables built in the grounds of The Durdans in 1881 and all three of his Derby-winning horses were eventually buried there, alongside an earlier Derby winner who had been owned by the previous owner of the house. Both the house and the stables are now listed buildings. Rosebery was also an avid book-collector and an author: as a young man, in 1862 he published a collection of poetry; in later life he wrote several political biographies, his subjects including William Pitt (1891), Sir Robert Peel (1899) and the Emperor Napoleon (1900).

Sir Michael Hicks Beach

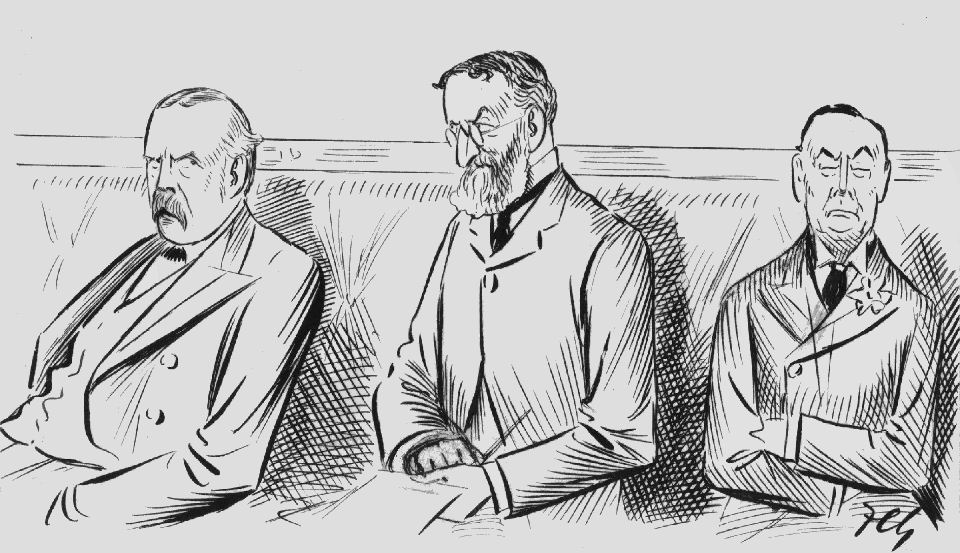

A sketch by Francis Carruthers Gould of three front benchers in Salisbury's last administration: Arthur Balfour (left), First Lord of the Treasury; Sir Michael Hicks Beach (centre), Chancellor of the Exchequer; and Joseph Chamberlain (right), Colonial Secretary.

Sir Michael Hicks Beach, Bt (1837-1916) was a Conservative politician. He was first elected to parliament in 1864, and served continuously until 1906, when he was raised to the peerage as the Viscount St Aldwyn. Under Disraeli, he served as Chief Secretary for Ireland from 1874-78 and as Secretary for the Colonies from 1878-80. He held Cabinet posts in each of Lord Salisbury's administrations: in Salisbury's brief first administration, from July 1885 to February 1886, he was Chancellor of the Exchequer and Leader of the House of Commons, and he was again Chancellor in Salisbury's third and last administration. When Salisbury announced his retirement, in July 1902, Hicks Beach also chose to retire from the government, though he remained in the Commons until his elevation to the peerage four years later.

In August 1901, Hicks Beach became Father of the House of Commons—a largely honorific title given to the member of the House with the longest period of continuous service. He relinquished this title on his elevation to the House of Lords.

During Hicks Beach's time as Chancellor, he was faced with the problem of financing the war in South Africa against the Boer republics of Transvaal and the Free State. Although by temperament a free trader, he recognised the need for additional sources of taxation and, in what was to be his last budget, in April 1902, he reimposed a small duty on imported corn (ie grain) that had been abolished over 30 years earlier. When, twelve months later, his successor as Chancellor, C T Ritchie, once again removed this duty, Hicks Beach found himself in the position of trying to defend the abolition of a duty that he had previously argued strenuously to impose. In July 1903, Hicks Beach chaired the first meetings of what became the Unionist Free Food League, which he subsequently served as president until October 1903, when he vacated the position in favour of the Duke of Devonshire. It was largely Hicks Beach's loyalty to his party and to Balfour that prevented the activities of the League from causing a split in the Unionist party.

C T Ritchie

C T Ritchie: a caricature by Carlo Pellegrini (‘Ape’), from Vanity Fair, 31 October 1885.

Charles Thompson Ritchie (1838-1906) was a Conservative politician. He served under Lord Salisbury as President of the Board of Trade from 1895-1900 and as Home Secretary from 1900-1902. When Salisbury retired, in 1902, his Chancellor of the Exchequer, Michael Hicks Beach, also took the opportunity to retire. The new Prime Minister, Arthur Balfour, chose Ritchie as his replacement. Ritchie served as Chancellor from August 1902 until September 1903.

Ritchie was a convinced free trader and in his first (and only) budget, in April 1903, he removed the tax on imported corn that had been imposed a year earlier by Hicks Beach. Against Ritchie’s opposition, Chamberlain had argued for the retention of this tax for non-Empire countries, with a remission of the tax in favour of the colonies, and he believed he had Cabinet support for this view. But while he was away in South Africa, Ritchie gained the support of Cabinet members for a repeal of the tax: his argument that it was politically undesirable was strengthened by the results in several by-elections, which saw the Unionists lose votes. Chamberlain’s response came in the form of his speech at Birmingham on 15 May 1903, which sparked the tariff reform debate.

In September 1903, Ritchie was one of three free traders in the Cabinet who chose to resign rather than support Balfour’s proposals for retaliatory tariffs. He subsequently joined the Unionist Free Food League and campaigned actively against Chamberlain’s proposals.

Henry Campbell-Bannerman

“The Opposition”: a caricature of Henry Campbell-Bannerman by Leslie Matthew Ward (‘Spy’), from Vanity Fair, 10 August 1899.

Sir Henry Campbell-Bannerman (1836-1908), commonly known as “C-B”, was a Liberal politician. He served briefly as Secretary of State for War under Gladstone in 1886 and held the same post again under Gladstone and then Rosebery from 1892-95. In February 1899 he succeeded Sir William Harcourt as leader of the Liberal party in opposition. In December 1905, following the resignation of Arthur Balfour as Prime Minister, Campbell-Bannerman formed a minority government; he promptly called a general election, which the Liberals won comfortably. Campbell-Bannerman resigned as Prime Minister in April 1908 because of ill health, and died 19 days later.

In May 1907, Campbell-Bannerman became Father of the House of Commons—a largely honorific title given to the member of the House with the longest period of continuous service. He is the only Prime Minister to have become Father of the House while in office: four others—Lloyd-George, Churchill, Callaghan and Heath—became Father of the House (Lloyd-George for 16 years), but none until several years after ceasing to be Prime Minister.

Campbell-Bannerman was a passionate believer in free trade. As he put it during a speech at Bolton in October 1903, “I oppose protection root and branch, veiled and unveiled, one-sided or reciprocal. I oppose it in any form.”

Institutions

The Cobden Club

The Cobden Club was a London gentlemen’s club. Founded in 1866, it took its name from Richard Cobden (1804-65), one of the principal opponents of the Corn Laws and chief architect of their repeal in 1846. Its stated object was to encourage “the growth and diffusion of those economic and political principles with which Cobden’s name is associated”.

The Cobden Club numbered among its members many of the leading proponents of free trade, and—unusually, for a gentlemen’s club—was very active politically, publishing pamphlets, arranging speeches, etc. It began organising a campaign against Chamberlain’s proposals within days of his speech in Birmingham, in May 1903.

The Cobden Club had numerous “honorary” members, many resident abroad. Although the Club, and many of these foreign members, vigorously denied that they had any influence on the policies or behaviour of the club, their presence among the membership led opponents of free trade to claim that the Cobden Club was being unduly influenced by “foreigners”, whose countries, if not they personally, had a vested interest in Britain’s continuing adherence to free trade policies.

The Tariff Reform League

The Tariff Reform League was ostensibly a non-political body, formed for the purpose of mobilising public support for Chamberlain’s proposals. Its supporters, who included Unionist MPs, businessmen and academics, held preliminary meetings, beginning in late May 1903, at the Duke of Sutherland’s London home before the League was formally inaugurated at a meeting on 21 July. The Duke was elected as president and Arthur Pearson, proprietor of the Daily Express, was elected as a member (and subsequently chairman) of the executive committee. A resolution passed at the inaugural meeting defined the purpose of the League as being

the development and defence of the industrial interests of the British Empire, its main object being to advocate the examination of the tariff with a view to its employment, to consolidate and develop the resources of the Empire, and to defend the industries of the United Kingdom.

Although Chamberlain was involved behind the scenes, his position as a Cabinet minister prevented him from direct association with the League, but he became one of its vice-presidents within weeks of resigning his ministerial office.

The Unionist Free Food League

The Unionist Free Food League was formed in July 1903, as a counter to the Tariff Reform League. Initially it was merely a committee of Unionist free trade MPs, chaired by a former Chancellor of the Exchequer, Sir Michael Hicks Beach, and with one of the “elder statesmen” of the Conservative party, Sir John Gorst as a vice-chairman. Some 60 Unionist MPs were associated with the League from the outset, including Winston Churchill and Lord Hugh Cecil. In order to allow particpation from non-parliamentarians, it was later formally constituted as the Unionist Free Food League, with Hicks Beach as its president. In mid-October, soon after the Duke of Devonshire’s resignation from the government, Hicks Beach invited him to join the League. Devonshire stipulated a number of conditions, the principal one being that the League should not interfere with the government’s right to lay measures before Parliament for approval, and when these conditions were accepted he joined the League and was elected as president, Hicks Beach, with C T Ritchie and Lord Goschen, being elected as vice-presidents.

An early circular letter from the League stated its aim as being “to counteract the active steps already taken by the advocates of the protective taxation on food“. A resolution passed by the committee on 30 July stated its aims more clearly:

The Unionist Free Food League is an association of supporters of his Majesty’s present Government formed for the purpose of placing before the people the objections hitherto generally entertained by the Unionist party, and maintained by every Conservative and Unionist Government since 1852, to the imposition of protective duties on food.

The Press

The fiscal debate took place before the age of radio or television; even photographs were used only sparingly, and not at all in most of the daily and weekly newspapers and periodicals. The audience for a major political speech was often limited by the capacity of the venue, and though the principal speakers—such as Chamberlain, Devonshire, Balfour, Rosebery—often spoke before 5,000 or more people, this was still only a fraction of the number who would read a report of the speech in their favourite newspaper the following day.

As a result, newspapers were almost entirely responsible for disseminating the views of politicians to the wider public, and they did so very much from whatever standpoint was dictated by their proprietors and editors. Very little of the reporting was objective, and many of the daily newspapers took an active role in shaping the debate. The Daily News, for example, was effectively a mouthpiece for the anti-imperialist faction of the Liberal party and was almost vitriolic in its attacks on Chamberlain. On the other side of the fence, the Daily Express (and its proprietor, Arthur Pearson) championed Chamberlain and lost no opportunity to ridicule his opponents (as can clearly be seen from the tone of the Parrot poems). The Daily Mail occupied a more ambivalent position: its proprietor, Alfred Harmsworth, admired Chamberlain but disapproved of his tariff reform crusade and the paper was initially highly critical of him, though by 1904 it was being identified as one of his supporters. The Times, while broadly favouring Chamberlain’s proposals, was almost alone in maintaining a degree of objectivity: while its editorials were usually critical of the opponents of tariff reform, its reporting was generally balanced and fairly represented the views of all concerned, and—unlike papers such as the News and Express—it regular allowed Chamberlain’s opponents a voice in the form of “Letters to the Editor”.

Among the weekly periodicals, the Westminster Gazette was noted for its judicious, albeit prejudiced, analysis; its principal cartoonist, F Carruthers Gould, made something of a career out of caricaturing Chamberlain. Punch, too, was generally anti-Chamberlain, though it is not always clear whether this represented a political stance or merely reflected the fact that, more than most of the other major personalities involved, he provided the best material for a cartoonist. The Illustrated London News, like the Times, was broadly pro-Chamberlain, but maintained a measured tone.