Liberty, July 21, 1928

Part Six

MR. CARMODY would have writhed in irritation at Hugo’s question, had not prudence reminded him that he was thirty feet too high in the air to do that sort of thing.

“Never mind what I’m doing up here! Help me down.”

“How did you get there?”

“Never mind how I got here!”

“But what,” persisted Hugo insatiably, “is the big—or general—idea?”

Withheld from the relief of writhing, Mr. Carmody gritted his teeth.

“Put that ladder up,” he said in a strained voice.

“Ladder?”

“Yes, ladder.”

“What ladder?”

“There is a ladder on the ground.”

“Where?”

“There. No, not there. There! There! Not there, I tell you. There! There!”

Hugo, following these directions, concluded a successful search.

“Right,” he said. “Ladder, long, wooden, for purposes of climbing, one. Correct as per memo. Now what?”

“Put it up.”

“Right.”

“And hold it very carefully.”

“Esteemed order booked,” said Hugo. “Carry on.”

“Are you sure you are holding it carefully?”

“As in a vise.”

“Well, don’t let go.”

Mr. Carmody, dying a considerable number of deaths in the process, descended.

He found his nephew’s curiosity at close range even more acute than it had been from a distance.

“What on earth were you doing up there?” said Hugo, starting again at the beginning.

“Never mind.”

“But what were you?”

“If you wish to know, a rung broke and the ladder slipped.”

“But what were you doing on a ladder?”

“NEVER mind!” cried Mr. Carmody, regretting more bitterly than ever before in his life that his late brother Eustace had not lived and died a bachelor. “Don’t keep saying what—what—what!”

“Well, why?” said Hugo, conceding the point. “Why were you climbing ladders?”

Mr. Carmody hesitated. His native intelligence returning, he perceived now that this was just what the great public would want to know. It was little use urging a human talking machine like his nephew to keep quiet and say nothing about this incident. In a couple of hours it would be all over Rudge. He thought swiftly.

“I fancied I saw a swallow’s nest under the eaves.”

“Swallow’s nest?”

“Swallow’s nest. The nest,” said Mr. Carmody between his teeth, “of a swallow.”

“Did you think swallows nested in July?”

“Why shouldn’t they?”

“Well, they don’t.”

“I never said they did. I merely said—”

“No swallow has ever nested in July.”

“I never—”

“April,” said our usually well informed correspondent.

“What?”

“April. Swallows nest in April.”

“Damn all swallows!” said Mr. Carmody.

And there was silence for a moment, while Hugo directed his keen young mind at other aspects of this strange affair.

“How long had you been up there?”

“I don’t know. Hours. Since half-past five.”

“Half-past five? You mean you got up at half-past five to look for swallows’ nests in July?”

“I did not get up to look for swallows’ nests.”

“But you said you were looking for swallows’ nests.”

“I did not say I was looking for swallows’ nests. I merely said I fancied I saw a swallow’s nest—”

“You couldn’t have done. Swallows don’t nest in July. April.”

The sun was peeping over the elms. Mr. Carmody raised his clenched fists to it.

“I did not say I saw a swallow’s nest. I said I thought I saw a swallow’s nest.”

“And got a ladder out and climbed up for it?”

“Yes.”

“Having arisen from your couch at five-thirty ante meridian?”

“Will you kindly stop asking me all these questions?”

Hugo regarded him thoughtfully.

“Just as you like, uncle. Well, anything further this morning? If not, I’ll be getting along and taking my dip.”

II

“I SAY, Ronnie,” said Hugo, some two hours later, meeting his friend en route for the breakfast table. “You know my uncle?”

“What about him?”

“He’s loopy.”

“What?”

“Gone clean off his casters. I found him at seven o’clock this morning sitting on a second floor window sill. He said he’d got up at five-thirty to look for swallows’ nests.”

“Bad,” said Mr. Fish, shaking his head with even more than his usual solemnity. “Second floor window sill, did you say?”

“Second floor window sill.”

“Exactly how my aunt started,” said Ronnie Fish. “They found her sitting on the roof of the stables, playing the ukulele in a blue dressing gown. She said she was Boadicea. And she wasn’t. That’s the point, old boy,” said Mr. Fish earnestly. “She wasn’t. We must get you out of this as quickly as possible, or before you know where you are you’ll find yourself being murdered in your bed. It’s this living in the country that does it. Six consecutive months in the country is enough to sap the intellect of anyone. Looking for swallows’ nests, was he?”

“So he said. And swallows don’t nest in July. They nest in April.”

Mr. Fish nodded.

“That’s how I always heard the story,” he agreed. “The whole thing looks very black to me, and the sooner you’re safe out of this and in London, the better.”

AT about the same moment Mr. Carmody was in earnest conference with Mr. Molloy.

“That man you were telling me about,” said Mr. Carmody. “That friend of yours who you said would help us.”

“Chimp?”

“I believe you referred to him as Chimp. How soon could you get in touch with him?”

“Right away, brother.”

Mr. Carmody objected to being called brother, but this was no time for being finicky.

“Send for him at once.”

“Why, have you given up the idea of getting that stuff out of the house yourself?”

“Entirely,” said Mr. Carmody. He shuddered slightly. “I have been thinking the matter over very carefully, and I feel that this is an affair where we require the services of some third party. Where is this friend of yours? In London?”

“No; he’s right around the corner. His name’s Twist. He runs a sort of health farm place only a few miles from here.”

“God bless my soul! Healthward Ho?”

“That’s the spot. Do you know it?”

“Why, I have only just returned from there.”

Mr. Molloy was conscious of a feeling of almost incredulous awe. It was the sort of feeling which would come to a man who saw miracles happening all round him. He could hardly believe that things could possibly run as smoothly as they appeared to be doing.

He had anticipated a certain amount of difficulty in selling Chimp Twist to Mr. Carmody, as he phrased it to himself, and had looked forward with not a little apprehension to a searching inquisition into Chimp Twist’s bona fides. And now, it seemed, Mr. Carmody knew Chimp personally and was, no doubt, prepared to receive him without a question. Could luck like this hold? That was the only thought that disturbed Mr. Molloy.

“Well, isn’t that interesting!” he said slowly. “So you know my old friend Twist, do you?”

“Yes,” said Mr. Carmody—speaking, however, as if the acquaintanceship were not one to which he looked back with any pleasure. “I know him very well.”

“Fine!” said Mr. Molloy. “You see, if I thought we were getting in somebody you knew nothing about and felt you couldn’t trust, it would sort of worry me.”

Mr. Carmody made no comment on this evidence of his guest’s nice feeling. He was meditating and did not hear it.

What he was meditating on was the agreeable fact that that money which he had been trying so vainly to recover from Dr. Twist would not be a dead loss, after all. He could write it off as part of the working expenses of this little venture.

He beamed happily at Mr. Molloy.

“Healthward Ho is on the telephone,” he said. “Go and speak to Dr. Twist now and ask him to come over here at once.”

He hesitated for a moment, then came bravely to a decision. After all, whatever the cost in petrol, oil, and depreciation of tires, it was for a good object. More working expenses.

“I will send my car for him,” he said.

If you wish to accumulate, you must inevitably speculate, felt Mr. Carmody.

III

THE strange depression which had come upon Pat in the shop of Chas. Bywater did not yield, as these gray moods generally do, to the curative influence of time. The following morning found her as gloomy as ever—indeed, rather gloomier; for shortly after breakfast the noblesse oblige spirit of the Wyverns had sent her on a reluctant visit to an old retainer, who lived—if you could call it that—in one of the smaller and stuffier houses in Budd Street.

Pensioned off after cooking for the Colonel for eighteen years, this female had retired to bed and stayed there. And there was a legend in the family—though neither by word nor by look did she ever give any indication of it—that she enjoyed seeing Pat.

Bedridden ladies of advanced age seldom bubble over with fun and joie de vivre. This one’s attitude toward life seemed to have been borrowed from her favorite light reading, the works of the prophet Jeremiah; and Pat, as she emerged into the sunshine after some eighty minutes of her society, was feeling rather like Jeremiah’s younger sister.

The sense of being in a world unworthy of her—a world cold and unsympathetic and full of an inferior grade of human being—had now become so oppressive that she was compelled to stop on her way home and linger on the old bridge which spanned the Skirme. From the days of her childhood this sleepy, peaceful spot had always been a haven when things went wrong.

She was gazing down into the slow moving water and waiting for it to exercise its old spell, when she heard her name spoken, and turned to see Hugo.

“What ho,” said Hugo, pausing beside her.

His manner was genial and unconcerned. He had not met her since that embarrassing scene in the lobby of the Hotel Lincoln, but he was a man on whom the memory of past embarrassments sat lightly.

“WHAT do you think you’re doing, young Pat?”

Pat found herself cheering up a little. She liked Hugo. The sense of being all alone in a bleak world left her.

“Nothing in particular,” she said. “Just looking at the water.”

“Which, in its proper place,” agreed Hugo, “is admirable stuff. I’ve been doing a bit of froth blowing at the Carmody Arms. Also buying cigarettes and other necessaries.

“I say, have you heard about my Uncle Lester’s brain coming unstuck? Absolutely. He’s quite non compos. Mad as a coot. Belfry one seething mass of bats. He’s taken to climbing ladders in the small hours after swallows’ nests.

“However, shelving that for the moment, I’m very glad I ran into you this morning, young Pat. I wish to have a serious talk with you about old John.”

“John?”

“John.”

“What about John?”

At this moment there whirred past, bearing in its interior a weedy, snub-nosed man with a waxed mustache, a large red automobile. Hugo, suspending his remarks, followed it with astonished eyes.

“Good Lord!”

“What about Johnny?”

“That was the Dex-Mayo,” said Hugo. “And the gargoyle inside was that blighter Twist from Healthward Ho. Great Scott! The car must have been over there to fetch him.”

“What’s so remarkable about that?”

“What’s so remarkable?” echoed Hugo, astounded. “What’s remarkable about Uncle Lester deliberately sending his car twenty miles to fetch a man who could have come, if he had to come at all, by train, at his own expense? My dear old thing, it’s revolutionary. It marks an epoch. Do you know what I think has happened? You remember that dynamite explosion in the park, when Uncle Lester nearly got done in?”

“I don’t have much chance to forget it.”

“Well, what I believe has happened is that the shock he got that day has completely changed his nature. It’s a well known thing. You hear of such cases all the time. Ronnie Fish was telling me about one only yesterday.

“There was a man he knew in London, a money lender, a fellow who had a glass eye, and the only thing that enabled anyone to tell which of his eyes was which was that the glass one had rather a more human expression than the other. That’s the sort of chap he was.

“Well, one day he was nearly conked in a railway accident, and he came out of hospital a different man. Slapped people on the back, patted children on the head, tore up I. O. Us., and talked about it being everybody’s duty to make the world a better place.

“Take it from me, young Pat, Uncle Lester’s whole nature has undergone some sort of rummy change like that. That swallow’s nest business must have been a preliminary symptom. Ronnie tells me that this money lender with the glass eye—”

PAT was not interested in glass-eyed money lenders.

“What were you saying about John?”

“I’ll tell you what I’m going to do. I’m going home quick, so as to be among those present when he starts scattering the stuff. It’s quite on the cards that I may scoop that five hundred yet. Once a tightwad starts seeing the light—”

“You were saying something about John,” said Pat, falling into step with him as he moved off.

His babble irked her, making her wish that she could put the clock back a few years. Age, they say, has its compensations, but one of the drawbacks of becoming grown up and sedate is that you have to abandon the childish practice of clumping your friends on the side of the head when they wander from the point. However, she was not too old to pinch her companion in the fleshy part of the arm, and she did so.

“Ouch!” said Hugo, coming out of his trance.

“What about John?”

HUGO massaged his arm tenderly. The look of a greyhound pursuing an electric hare died out of his eyes.

“Of course, yes. John. Glad you reminded me. Have you seen John lately?”

“No. I’m not allowed to go to the Hall, and he seems too busy to come and see me.”

“It isn’t so much being busy. Don’t forget there’s a war on. No doubt he’s afraid of bumping into the parent.”

“If Johnny’s scared of father—”

“There’s no need to speak in that contemptuous tone. I am, and there are few more intrepid men alive than Hugo Carmody. The old Colonel, believe me, is a tough baby. If I ever see him, I shall run like a rabbit, and my biographers may make of it what they will.

“You, being his daughter and having got accustomed to his ways, probably look on him as something quite ordinary and harmless; but even you will admit that he’s got eyebrows which must be seen to be believed.”

“Oh, never mind father’s eyebrows. Go on about Johnny.”

“Right ho. Well, then, look here, young Pat,” said Hugo earnestly, “in the matter of the aforesaid John, I want to ask you a favor. I understand he proposed to you that night at the Mustard Spoon.”

“Well?”

“And you slipped him the mitten.”

“Well?”

“Oh, don’t think I’m blaming you,” Hugo assured her. “If you don’t want him, you don’t. Nothing could be fairer than that. But what I’m asking you to do now is to keep clear of the poor chap. If you happen to run into him, that can’t be helped; but be a sport and do your best to avoid him.

“Don’t unsettle him. If you come buzzing round, stirring memories of the past and arousing thoughts of auld lang syne and what not, that’ll unsettle him. It’ll take his mind off his job and—well—unsettle him. And, providing he isn’t unsettled, I have strong hopes that we may get old John off this season. Do I make myself clear?”

PAT kicked viciously at an inoffensive pebble, whose only fault was that it happened to be within reach at the moment.

“I suppose what you’re trying to break to me in your rambling, woolen headed way is that Johnny is mooning round that Molloy girl? I met her just now in Bywater’s, and she told me she was staying at the Hall.”

“I wouldn’t call it mooning,” said Hugo thoughtfully, speaking like a man who is an expert in these matters and can appraise subtle values. “I wouldn’t say it had quite reached the mooning stage yet. But I have hopes. You see, John is a bloke whom nature intended for a married man. He’s a confirmed settler down, the sort of chap who—”

“You needn’t go over all that again. I had the pleasure of hearing your views on the subject that night in the lobby of the hotel.”

“Oh, you did hear?” said Hugo, unabashed. “Well, don’t you think I’m right?”

“If you mean do I approve of Johnny marrying Miss Molloy, I certainly do not.”

“But if you don’t want him—”

“It has nothing to do with my wanting him or not wanting him. I don’t like Miss Molloy.”

“Why not?”

“She’s flashy.”

“I would have said smart.”

“I wouldn’t.”

Pat, with an effort, recovered a certain measure of calm. Wrangling, she felt, was beneath her. Since she could not hit Hugo with the basket in which she had carried two pounds of tea, a bunch of roses, and a seed cake to her bedridden pensioner, the best thing to do was to preserve a ladylike composure.

“Anyway, you’re probably taking a lot for granted. Probably Johnny isn’t in the least attracted by her. Has he ever given any sign of it?”

“Sign?” Hugo considered. “It depends on what you mean by sign. You know what old John is. One of these strong, silent fellows who look on all occasions like a stuffed frog.”

“He doesn’t!”

“Pardon me,” said Hugo firmly. “Have you ever seen a stuffed frog? Well, I have. I had one for years when I was a kid. And John has exactly the same power of expressing emotion. You can’t go by what he says or the way he looks. You have to keep an eye out for much subtler bits of evidence.

“Now, last night he was explaining the rules of cricket to this girl, and answering all her questions on the subject, and, as he didn’t at any point in the proceedings punch her on the nose, one is entitled to deduce, I consider, that he must be strongly attracted by her. Ronnie thinks so, too. So what I’m asking you to do—”

“Good-by,” said Pat.

They had reached the gate of the little drive that led to her house, and she turned in sharply.

“Eh?”

“Good-by.”

“But, just a moment,” insisted Hugo. “Will you—”

At this point he stopped in midsentence and began to walk quickly up the road. And Pat, puzzled to conjecture the reason for so abrupt a departure, received illumination a moment later when she saw her father coming down the drive.

Colonel Wyvern had been dealing murderously with snails in the shadow of a bush, and the expression on his face seemed to indicate that he would be glad to extend the treatment to Hugo.

He gazed after that officious young man with a steely eye. The second post had arrived a short time before, and it had included, among a number of bills and circulars, a letter from his lawyer, in which the latter regretfully gave it as his opinion that an action against Mr. Lester Carmody in the matter of that dynamite business would not lie. To bring such an action would, in the judgment of Colonel Wyvern’s lawyer, be a waste both of time and money.

The communication was not calculated to sweeten the Colonel’s temper, nor did the spectacle of his daughter in apparently pleasant conversation with one of the enemy help to cheer him up.

“What were you talking about to that fellow?” he demanded. It was rare for Colonel Wyvern to be the heavy father, but there are times when heaviness in a father is excusable. “Where did you meet him?”

HIS tone disagreeably affected Pat’s already harrowed nerves, but she replied to the questions equably.

“I met him on the bridge. We were talking about John.”

“Well, kindly understand that I don’t want you to hold any communication whatsoever with that young man or his cousin John or his infernal uncle or any of that Hall gang! Is that clear?”

Her father was looking at her as if she were a snail which he had just found eating one of his lettuce leaves; but Pat still contrived with some difficulty to preserve a pale, saintlike calm.

“Quite clear.”

“Very well, then.”

There was a silence.

“I’ve known Johnny fourteen years,” said Pat in a small voice.

“Quite long enough,” grunted Colonel Wyvern.

Pat walked on into the house and up the stairs to her room.

There, having stamped on the basket and reduced it to a state where it would never again carry seed cake to ex-cooks, she sat on her bed and stared, dry eyed, at her reflection in the mirror.

What with Dolly Molloy and Hugo and her father, the whole aspect of John Carroll seemed to be changing for her. No longer was she able to think of him as poor old Johnny. He had the glamour now of something unattainable and greatly to be desired. She looked back at a night, some centuries ago, when a fool of a girl had refused the offer of this superman’s love, and shuddered to think what a mess of things girls can make.

And she had no one to confide in. The only person who could have understood and sympathized with her was Hugo’s glass-eyed money lender. He knew what it was to change one’s outlook.

IV

MEANWHILE Mr. Alexander (Chimp) Twist stood with his shoulders against the mantelpiece in Mr. Carmody’s study and, twirling his waxed mustache thoughtfully, listened with an expressionless face to Soapy Molloy’s synopsis of the events which had led up to his being at the Hall this morning.

Dolly reclined in a deep armchair. Mr. Carmody was not present, having stated that he preferred to leave the negotiations entirely to Mr. Molloy.

Through the open window the sounds and scents of summer poured in; but it is unlikely that Chimp Twist was aware of them. He was a man who believed in concentration, and his whole attention now was taken up by the remarkable facts which his old acquaintance and partner was placing before him.

The latter’s conversation on the telephone some two hours before had left Chimp Twist with an open mind. He was hopeful, but cautiously hopeful. Soapy had insisted that there was a big thing on, but he had reserved his enthusiasm until he should learn the details.

The thing, he felt, might seem big to Soapy, but to Alexander Twist no things were big things unless he could see in advance a substantial profit for A. Twist in them.

Mr. Molloy, concluding his story, paused for a reply. The visitor gave his mustache a final twist, and shook his head.

“I don’t get it,” he said.

Mrs. Molloy straightened herself militantly in her chair.

Of all masculine defects, she liked slowness of wit least; and she had never been a great admirer of Mr. Twist.

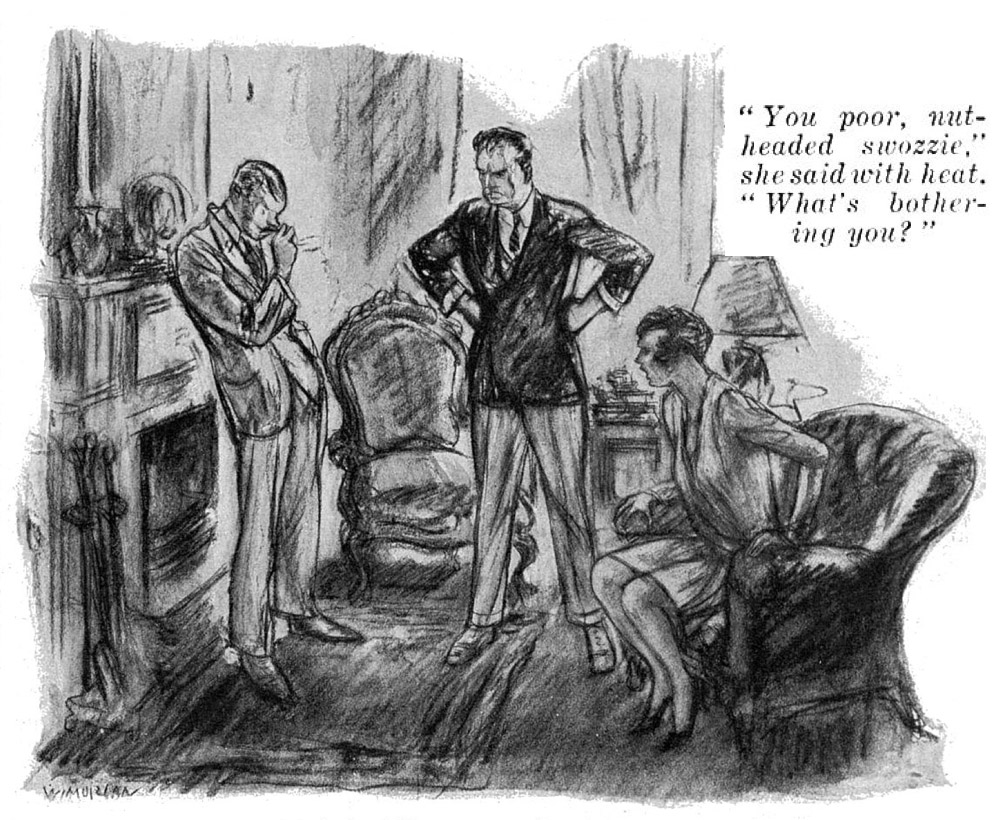

“You poor, nut-headed swozzie,” she said with heat. “What don’t you get? It’s simple enough, isn’t it? What’s bothering you?”

“There’s a catch somewhere. Why isn’t this guy Carmody able to sell the things?”

“It’s the law, you poor fish. Soapy explained all that.”

“Not to me he didn’t,” said Chimp. “A lot of words fluttered out of him, but they didn’t explain anything to me. Do you mean to say there’s a law in this country that says a man can’t sell his own property?”

“It isn’t his own property.” Dolly’s voice was shrill with exasperation. “The things belong in the family and have to be kept there. Does that penetrate, or have we got to use a steam drill?

“Listen here. Old George W. Ancestor starts one of these English families going—way back in the year G. Z. something. He says to himself, ‘I can’t last forever, and when I go, then what? My son Freddy is a good boy, handy with the battle-ax and okay at mounting his charger, but he’s like all the rest of these kids—you can’t keep him away from the hock shop as long as there’s anything in the house he can raise money on. It begins to look like, the moment I’m gone, my collection of old antiques can kiss itself good-by.’

“And then he gets an idea. He has a law passed saying that Freddy can use the stuff as long as he lives, but he can’t sell it. And Freddy, when his time comes, he hands the law on to his son Archibald, and so on, down the line till you get to this here now Carmody.

“The only way this Carmody can realize on all these things is to sit in with somebody who’ll pinch them and then salt them away somewheres, so that after the cops are out of the house and all the fuss has quieted down they can get together and do a deal.”

Chimp’s face cleared.

“Now I’m hep,” he said. “Now I see what you’re driving at. Why couldn’t Soapy have put it like that before? Well, then, what’s the idea? I sneak in and swipe the stuff. Then what?”

“You salt it away.”

“At Healthward Ho?”

“No!” said Mr. Molloy.

“No!” said Mrs. Molloy.

It would have been difficult to say which spoke with the greater emphasis, and the effect was to create a rather embarrassing silence.

“IT isn’t that we don’t trust you, Chimpie,” said Mr. Molloy, when this silence had lasted some little time.

“Oh?” said Mr. Twist, rather distantly.

“It’s simply that this bimbo Carmody naturally don’t want the stuff to go out of the house. He wants it where he can keep an eye on it.”

“How are you going to pinch it without taking it out of the house?”

“That’s all been fixed. I was talking to him about it this morning after I phoned you. Here’s the idea. You get the stuff and pack it away in a suitcase—”

“Stuff that there’s only enough of so’s you can put it all in a suitcase is a hell of a lot of use to anyone,” commented Mr. Twist disparagingly.

Dolly clutched her temples. Mr. Molloy brushed his hair back from his forehead with a despairing gesture.

“Sweet potatoes!” moaned Dolly. “If you had another brain you’d just have one. A thing hasn’t got to be the size of the Singer Building to be valuable, has it? I suppose if someone offered you a diamond, you’d turn it down because it wasn’t no bigger than a hen’s egg.”

“Diamond?” Chimp brightened. “Are there diamonds?”

“No, there aren’t. But there’s pictures and things, any one of them worth a packet. Go on, Soapy; tell him.”

Mr. Molloy smoothed his hair and addressed himself to his task once more.

“Well, it’s like this, Chimpie,” he said. “You put the stuff in a suitcase and you take it down into the hall, where there’s a closet under the stairs—”

“We’ll show you the closet,” interjected Dolly.

“Sure, we’ll show you the closet,” said Mr. Molloy generously. “Well, you put the suitcase in this closet and you leave it lay there. The idea is that later on I give old man Carmody my check and he hands it over and we take it away.”

“He thinks Soapy owns a museum in America,” explained Dolly. “He thinks Soapy’s got all the money in the world.”

“Of course, long before the time comes for giving any checks, we’ll have got the stuff away.”

MR. CHIMP digested this.

“Who’s going to buy it, when you do get it away?” he asked.

“Oh, gee!” said Dolly. “You know as well as I do there’s dozens of people on the other side who’ll buy it.”

“And how are you going to get it away, if it’s in a closet in Carmody’s house, and Carmody has the key—”

“Now, there,” said Mr. Molloy, with a deferential glance at his wife, as if requesting her permission to reopen a delicate subject, “the madam and I had a kind of an argument. I wanted to wait till a chance came along sort of natural; but Dolly’s all for quick action. You know what women are. Impetuous.”

“If you’d care to know what we’re going to do,” said Mrs. Molloy definitely, “we’re not going to hang around waiting for any chances to come along sort of natural. We’re going to slip a couple of knock-out drops in old man Carmody’s port one night after dinner, and clear out with the stuff while—”

“Knock-out drops?” said Chimp, impressed. “Have you got any knock-out drops?”

“Sure we’ve got knock-out drops. Soapy never travels without them.”

“The madam always packs them in their little bottle first thing, before even my clean collars,” said Mr. Molloy proudly. “So you see, everything’s all arranged.”

“Yeah?” said Mr. Twist. “And how about me?”

“How do you mean, how about you?”

“It seems to me,” pointed out Mr. Twist, eying his business partner in rather an unpleasant manner with his beady little eyes, “that you’re asking me to take a pretty big chance. While you’re doping the old man, I’ll be twenty miles away at Healthward Ho. How am I to know you won’t go off with the stuff and leave me to whistle for my share?”

It is only occasionally that one sees a man who cannot believe his ears; but anybody who had been in Mr. Carmody’s study at this moment would have been able to enjoy that interesting experience. A long moment of stunned and horrified amazement passed before Mr. Molloy was able to decide that he really had heard correctly.

“Chimpie! You don’t suppose we’d double-cross you?”

“Ee-magine!” said Mrs. Molloy.

“Well, mind you don’t,” said Mr. Twist coldly. “But you can’t say I’m not taking a chance. And now, talking turkey for a moment, how do we share?”

“Equal shares, of course, Chimpie.”

“You mean half for me and half for you and Dolly?”

Mr. Molloy winced as if the mere suggestion had touched an exposed nerve.

“No, no, no, Chimpie! You get a third, I get a third, and the madam gets a third.”

“Not on your life!”

“Not on your life!”

“What?”

“Not on your life! What do you think I am?”

“I don’t know,” said Mrs. Molloy acidly. “But, whatever it is, you’re the only one of it.”

“Is that so?”

“Yes, that is so.”

“Now, now, now,” said Mr. Molloy, intervening. “Let’s not get personal. I can’t figure this thing out, Chimpie. I can’t see where your kick comes in. You surely aren’t suggesting that you should ought to have as much as I and the wife put together?”

“No, I’m not. I’m suggesting I ought to have more.”

“What!”

“Sixty-forty’s my terms.”

A FEVERISH cry rang through the room. The temperamental Mrs. Molloy was very near the point past which a sensitive woman cannot be pushed.

“Every time we get together on one of these jobs,” she said, with deep emotion, “we always have this same fuss about the divvying up. Just when everything looks nice and settled, you start this thing of trying to hand I and Soapy the nub end of the deal. What’s the matter with you, that you always want the earth? Be human, why can’t you, you poor lump of Camembert.”

“I’m human, all right.”

“You’ve got to prove it to me.”

“What makes you say I’m not human?”

“Well, look in the glass and see for yourself,” said Mrs. Molloy offensively.

The pacific Mr. Molloy felt it time to call the meeting to order once more.

“Now, now, now! All this isn’t getting us anywheres. Let’s stick to business. Where do you get that sixty-forty stuff, Chimp?”

“I’ll tell you where I get it. I’m going into this thing as a favor, aren’t I? There’s no need for me to sit in at this game at all, is there? I’ve got a good, flourishing, respectable business of my own, haven’t I? A business that’s on the level. Well, then!”

DOLLY sniffed. Her husband’s soothing intervention had failed signally to diminish her animosity.

“I don’t know what your idea was in starting that Healthward Ho joint,” she said, “but I’ll bet my diamond sunburst it isn’t on the level.”

“Certainly it’s on the level. A man with brains can always make a good living without descending to anything low and crooked. That’s why I say that if I go into this thing it will simply be because I want to do a favor to two old friends.”

“Old what?”

“Friends was what I said,” repeated Mr. Twist. “If you don’t like my terms, say so, and we’ll call the deal off. It’ll be all right by me. I’ll simply get along back to Healthward Ho and go on running my good, flourishing, respectable business. Come to think of it, I’m not any too sold on this thing, anyway. I was walking in my garden this morning, and a magpie come up to me as close as that.”

Mrs. Molloy expressed the view that this was tough on the magpie, but wanted to know what the bird’s misfortune in finding itself so close to Mr. Twist that it could not avoid taking a good, square look at him had to do with the case.

“Well, I’m superstitious, same as everyone else.”

“Oh, stop stringing the beads and talk sense,” said Dolly wearily.

“I’m talking sense, all right. Sixty per cent or I don’t come in. You wouldn’t have asked me to come in if you could have done without me. Think I don’t know that? Sixty’s moderate. I’m doing all the hard work, aren’t I?”

“Hard work?” Dolly laughed bitterly. “Everybody’ll be out of the house on the night of this concert thing they’re having down in the village, there’ll be a window left open, and you’ll just walk in and pack up the stuff. If that’s hard, what’s easy? We’re simply handing you slathers of money for practically doing nothing.”

“Sixty,” said Mr. Twist. “And that’s my last word.”

“But, Chimpie—” pleaded Mr. Molloy.

“Sixty.”

“Have a heart!”

“Sixty.”

“It isn’t as though—”

“Sixty.”

Dolly threw up her hands despairingly.

“Oh, give it to him,” she said. “He won’t be happy if you don’t. If a guy’s middle name is Shylock, where’s the use wasting time trying to do anything about it?”

All right. They agreed to give it to him. But you must not read, in next week’s issue, what happened to that agreement, and what happened to those concerned, if laughter is bad for you.

Madame Eulalie’s Rare Plums

Madame Eulalie’s Rare Plums