Liberty, July 28, 1928

Part Seven

MRS. MOLLOY’S prediction that on the night of Rudge’s annual dramatic and musical entertainment the Hall would be completely emptied of its occupants was not, as it happened, literally fulfilled. A wanderer through the stable yard at about the hour of 10 would have perceived a light in an upper window; and, had he taken the trouble to get a ladder and climb up and look in, would have beheld John Carroll seated at his table, busy with a pile of accounts.

In an age so notoriously avid of pleasure as the one in which we live, it is rare to find a young man of such sterling character that he voluntarily absents himself from a village concert in order to sit at home and work; and, contemplating John, one feels quite a glow.

It was not as if he had been unaware of what he was missing. The vicar, he knew, was to open the proceedings with a short address; the choir would sing old English glees; the Misses Vivien and Alice Pond-Pond were down on the program for refined coon songs; and, in addition to other items too numerous and fascinating to mention, Hugo Carmody and his friend Mr. Fish would positively appear in person and render that noble example of Shakespeare’s genius, the Quarrel Scene from Julius Cæsar.

Yet John Carroll sat in his room, working. England’s future cannot be so dubious as the pessimists would have us believe while her younger generation is made of stuff like this.

John, in these days, was finding a good deal of consolation in his work. There is probably no better corrective of the pangs of hopeless love than real, steady application to the prosaic details of an estate. The heart finds it difficult to ache its hardest while the mind is busy with such items as “£61 8s. 5d., due to Messrs. Truby & Gaunt for Fixing Gas Engine,” or the claim of the Country Gentleman’s Association for £8 8s. 4d. for seeds. Add drains, manure, and feed of pigs, and you find yourself immediately in an atmosphere where Romeo himself would have let his mind wander.

John, as he worked, was conscious of a distinct easing of the strain that had been on him since his return to the Hall. And if at intervals he allowed his eyes to stray to the photograph of Pat on the mantelpiece, that was the sort of thing which might happen to any young man, and could not be helped.

It was seldom that visitors penetrated to this room of his—indeed, he had chosen to live above the stables in preference to inside the house for this very reason. And on Rudge’s big night he had looked forward to an unbroken solitude. He was surprised, therefore, as he checked the account of the Messrs. Vanderschoot & Son for bulbs, to hear footsteps on the stairs. A moment later the door opened and Hugo walked in.

JOHN’S first impulse, as always when his cousin paid him a visit, was to tell him to get out. People who, when they saw Hugo, immediately told him to get out generally had the comfortable feeling that they were doing the right and sensible thing. But tonight there was in his demeanor something so crushed and forlorn that John had not the heart to pursue this admirable policy.

“Hullo,” he said. “I thought you were down at the concert.”

Hugo uttered a short, bitter laugh, and, sinking into a chair, stared bleakly before him. His eyelids, like those of the Mona Lisa, were a little weary. He looked like the hero of a Russian novel debating the advisability of murdering a few near relations before hanging himself in the barn.

“I was,” he said. “Oh, yes; I was down at the concert, all right.”

“Have you done your bit already?”

“I have. They put Ronnie and me on just after the Vicar’s Short Address.”

“Wanted to get the worst over quick, eh?”

Hugo raised a protesting hand. There was infinite sadness in the gesture.

“Don’t mock, John. Don’t jeer. Don’t gibe and scoff. I’m a broken man.”

“Only cracked, I should have said.”

Hugo was not attuned to cousinly badinage. He frowned austerely.

“Less back chat,” he begged. “I came here for sympathy. And a drink. Have you got anything to drink?”

“There’s some whisky in that cupboard.”

Hugo heaved himself from the chair, looking more Russian than ever. John watched his operations with some concern.

“Aren’t you mixing it pretty strong?”

“I need it strong.”

The unhappy man emptied his glass, refilled it, and returned to the chair.

“In fact, it’s a point verging very much on the moot whether I ought to have put any water in at all.”

“What’s the trouble?”

“This isn’t bad whisky,” said Hugo, becoming a little brighter.

“I know it isn’t. What’s the matter?”

The momentary flicker of cheerfulness died out. Gloom once more claimed Hugo for its own.

“John, old man,” he said, “we got the bird.”

“Yes?”

“Don’t say ‘Yes?’ like that, as if you had expected it,” said Hugo, hurt. “The thing came on me as a stunning blow. I was amazed. Astounded. Absolutely nonplused.”

“Could I have knocked you down with a feather?”

“I thought we were going to be a riot. Of course, mind you, we came on much too early. It was criminal to bill us next to opening. An audience needs careful warming up for an intellectual act like ours.”

“What happened?”

Hugo rose and renewed the contents of his glass.

“There is a spirit creeping into the life of Rudge-in-the-Vale,” he said, “which I don’t like to see. A spirit of lawlessness and license. Disruptive influences are at work. Bolshevik propaganda, I shouldn’t wonder. Would a Rudge audience have given me the bird a few years ago? Not a chance!”

“But you’ve never tried them with the Quarrel Scene from Julius Cæsar before. Everybody has a breaking point.”

The argument was specious, but Hugo shook his head.

“In the good old days I could have done Hamlet’s Soliloquy and the hall would have rung with hearty cheers. It’s just this modern lawlessness and bolshevism.

“There was a very tough collection of the Budd Street element standing at the back who should never have been let in. They started straight away chiyiking the Vicar during his Short Address.

“I didn’t think anything of it at the time. I merely supposed that they wanted him to cheese it and let the entertainment start. I thought that directly Ronnie and I came on we should grip them. But we were barely a third of the way through when there were loud cries of ‘Tripe!’ and ‘Get off!’ ”

“I see what that meant. You hadn’t gripped them.”

“I was never so surprised in my life! Mark you, I’ll admit that Ronnie was perfectly rotten. He kept foozling his lines and saying, ‘Oh, sorry!’ and going back and repeating them. You can’t get the best out of Shakespeare that way.

“THE fact is, poor old Ronnie is feeling a little low just now. He got a letter this morning from his man Bessemer in London, a fellow who has been with him for years and has few equals as a trouser presser, springing the news out of an absolutely clear sky that he’s been secretly engaged for weeks and is just going to get married and leave Ronnie. Naturally, it has upset the poor chap badly. With a thing like that on his mind, he should never have attempted an exacting part like Brutus in the Quarrel Scene.”

“Just what the audience thought, apparently. What happened after that?”

“Well, we buzzed along as well as we could, and we had just got to that bit about digesting the venom of your spleen, though it do split you, when the proletariat suddenly started bunging vegetables.”

“Vegetables?”

“Turnips, mostly, as far as I could gather. Now, do you see the significance of that, John?”

“How do you mean, the significance?”

“Well, obviously these blighters had come prepared. They had meant to make trouble right along. If not, why would they have come to a concert with their pockets bulging with turnips?”

“They probably knew by instinct that they would need them.”

“No! It was simply this bally bolshevism one reads so much about.”

“You think these men were in the pay of Moscow?”

“I shouldn’t wonder. Well, that took us off. Ronnie got rather a beefy whack on the side of the head and exited rapidly. And I wasn’t going to stand out there doing the Quarrel Scene by myself, so I exited too. The last I saw, Chas. Bywater had gone on and was telling Irish dialect stories with a Swedish accent.”

“Did they throw turnips at him?”

“Not one! That’s the sinister part of it. That’s what makes me so sure the thing was an organized outbreak and all part of this class war you hear about. Chas. Bywater, in spite of the fact that his material is blue round the edges, goes like a breeze and gets off without a single turnip; whereas Ronnie and I—

“Well,” said Hugo, a hideous grimness in his voice, “this has settled one thing. I’ve performed for the last time for Rudge-in-the-Vale. Next year, when they come to me and plead with me to help out with the program, I shall reply, ‘Not after what has occurred!’ Well, thanks for the drink. I’ll be buzzing along.”

Hugo rose and wandered somnambulistically to the table.

“What are you doing?”

“Working.”

“Working?”

“Yes, working.”

“What at?”

“Accounts. Stop fiddling with those papers, curse you.”

“What’s this thing?”

“That,” said John, removing it from Hugo’s listless grasp and putting it out of reach in a drawer, “is the diagram of a thing called an alpha separator. It works by centrifugal force and can separate two thousand seven hundred and twenty-four quarts of milk in an hour. It has also a Holstein butter churner attachment and a boiler which at seventy degrees Centigrade destroys the obligatory and optional bacteria.”

“Yes?”

“Positively.”

“Oh? Well, damn it, anyway,” said Hugo.

HUGO crossed the strip of gravel which lay between the stable yard and the house, and, having found in his trousers pocket the key of the back door, proceeded to let himself in. His objective was the dining room. He was feeling so much better after the refreshment of which he had just partaken that reason told him he had found the right treatment for his complaint. A few more swift ones from the cellaret in the dining room, and the depression caused by the despicable behavior of the Budd Street bolshevists might possibly leave him altogether.

The passage leading to his goal was in darkness, but he moved steadily forward. Occasionally a chair would dart from its place to crack him over the shin, but he was not to be kept from the cellaret by trifles like that. Soon his fingers were on the handle of the door, and he flung it open and entered. And it was at this moment that there came to his ears an odd noise.

It was not the noise itself that was odd. Feet scraping on gravel always make that unmistakable sound. What impressed itself on Hugo as curious was the fact that, on the gravel outside the dining room window, feet at this hour should be scraping at all.

His hand had been outstretched to switch on the light, but now he paused. He waited, listening. And presently, in the oblong of the middle of the three large windows, he saw dimly, against the lesser darkness outside, a human body. It was insinuating itself through the opening; and what Hugo felt about it was that he liked its dashed nerve.

Hugo Carmody was no poltroon. Both physically and morally, he possessed more than the normal store of courage. At Cambridge he had boxed for his university in the lightweight division; and once, in London, the petty cash having run short, he had tipped a hat-check boy with an aspirin tablet. Moreover, although it was his impression that the few drops of whisky which he had drunk in John’s room had but scratched the surface, their effect in reality had been rather pronounced.

“IN some diatheses,” an eminent physician has laid down, “whisky is not immediately pathogenic. In other cases the spirit in question produces marked cachexia.”

Hugo’s cachexia was very marked indeed. He would have resented keenly the suggestion that he was fried, boiled, or even sozzled; but he was unquestionably in a definite condition of cachexia.

In a situation, accordingly, in which many householders might have quailed, he was filled with a gay exhilaration. He felt able and willing to chew the head off any burglar that ever packed a centerbit.

Glowing with cachexia and the spirit of adventure, he switched on the light and found himself standing face to face with a small, weedy man beneath whose snub nose there nestled a waxed mustache.

“Stand, ho!” said Hugo jubilantly, falling at once into the vein of the Quarrel Scene.

In the bosom of the intruder many emotions were competing for precedence; but jubilation was not one of them. If Mr. Twist had had a weak heart, he would by now have been lying on the floor breathing his last, for few people can ever have had a nastier shock. He stood congealed, blinking at Hugo.

Hugo, meanwhile, had made the interesting discovery that it was no stranger who stood before him, but an old acquaintance.

“Great Scott!” he exclaimed. “Old Doc Twist! The beautiful, tranquil thoughts bird!”

He chuckled joyously. His was a retentive memory, and he could never forget that this man had once come within an ace of ruining that big deal in cigarettes over at Healthward Ho, and had also callously refused to lend him a tenner. Of such a man he could believe anything, even that he combined with the duties of a physical culture expert a little housebreaking and burglary on the side.

“Well, well, well!” said Hugo. “ ‘Remember March, the ides of March remember: Did not great Julius bleed for justice’ sake? What villain touch’d his body, that did stab, and not for justice?’ Answer me that, you blighter—yes or no?”

Chimp Twist licked his lips nervously. He was a little uncertain as to the exact import of his companion’s last words, but almost any words would have found in him at this moment a distrait listener.

“ ‘Oh! I could weep my spirit from mine eyes,’ ” said Hugo.

Chimp could have done the same. With an intense bitterness he was regretting that he had ever allowed Mr. Molloy to persuade him into this rash venture. But he was a man of resource. He made an effort to mend matters.

Soapy, in a similar situation, would have done it better; but Chimp, though not possessing his old friend’s glib tongue and insinuating manners, did the best he could.

“You startled me,” he said, smiling a sickly smile.

“I bet I did!” agreed Hugo cordially.

“I came to see your uncle.”

“You what?”

“I came to see your uncle.”

“Twist, you lie! And, what is more, you lie in your teeth.”

“Now, see here!” began Chimp, with a feeble attempt at belligerence.

Hugo checked him with a gesture.

“ ‘There is no terror, Cassius, in your threats; for I am armed so strong in honesty that they pass by me like the idle wind, which I respect not. Must I give way and room to your rash choler? Shall I be frighted when a madman stares? By the gods, you shall digest the venom of your spleen, though it do split you.’ And what could be fairer than that?” said Hugo.

Mr. Twist was discouraged, but he persevered:

“I guess it looked funny to you, seeing me come in through a window. But, you see, I rang the front door bell and couldn’t seem to make anyone hear.”

“ ‘Away, slight man!’ ”

“You want me to go away?” said Mr. Twist, with a gleam of hope.

“You stay where you are, unless you’d like me to lean a decanter of the best port up against your head,” said Hugo. “And don’t flicker,” he added, awakening to another grievance against this unpleasant little man.

“Don’t what?” inquired Mr. Twist, puzzled, but anxious to oblige.

“Flicker. Your outline keeps wabbling, and I don’t like it. And there’s another thing about you that I don’t like. I’ve forgotten what it is for the moment, but it’ll come back to me soon.”

He frowned darkly; and, for the first time, it was borne in upon Mr. Twist that his young host was not altogether himself. There was a gleam in his eyes which, in Mr. Twist’s opinion, was far too wild to be agreeable.

“I know,” said Hugo, having reflected. “It’s your mustache.”

“My mustache?”

“Or whatever it is that’s broken out on your upper lip. I dislike it intensely. ‘When Cæsar lived,’ ” said Hugo querulously, “ ‘he durst not thus have moved me.’ And the worst thing of all is that you should have taken a quiet, harmless country house and called it such a beastly, repulsive name as Healthward Ho.

“GREAT Scott!” exclaimed Hugo. “I knew there was something I was forgetting. All this while you ought to have been doing bending and stretching exercises!”

“Your uncle, I guess, is still down at that concert thing in the village?” said Mr. Twist, weakly endeavoring to change the conversation.

Hugo started. A look of the keenest suspicion flashed into his eyes.

“Were you at that concert?” he said sternly.

“Me? No.”

“Are you sure, Twist? Look me in the face.”

“I’ve never been near any concert.”

“I strongly suspect you,” said Hugo, “of being one of the ringleaders in that concerted plot to give me the bird. I think I recognized you.”

“Not me.”

“You’re sure?”

“Sure.”

“Oh? Well, that doesn’t alter the cardinal fact that you are the bloke who makes poor, unfortunate fat men do bending and stretching exercises. So do a few now yourself.”

“Eh?”

“Bend!” said Hugo. “Stretch!”

“Stretch?”

“And bend,” said Hugo, insisting on full measure. “First bend, then stretch. Let me see your chest expand and hear the tinkle of buttons as you burst your waistcoat asunder.”

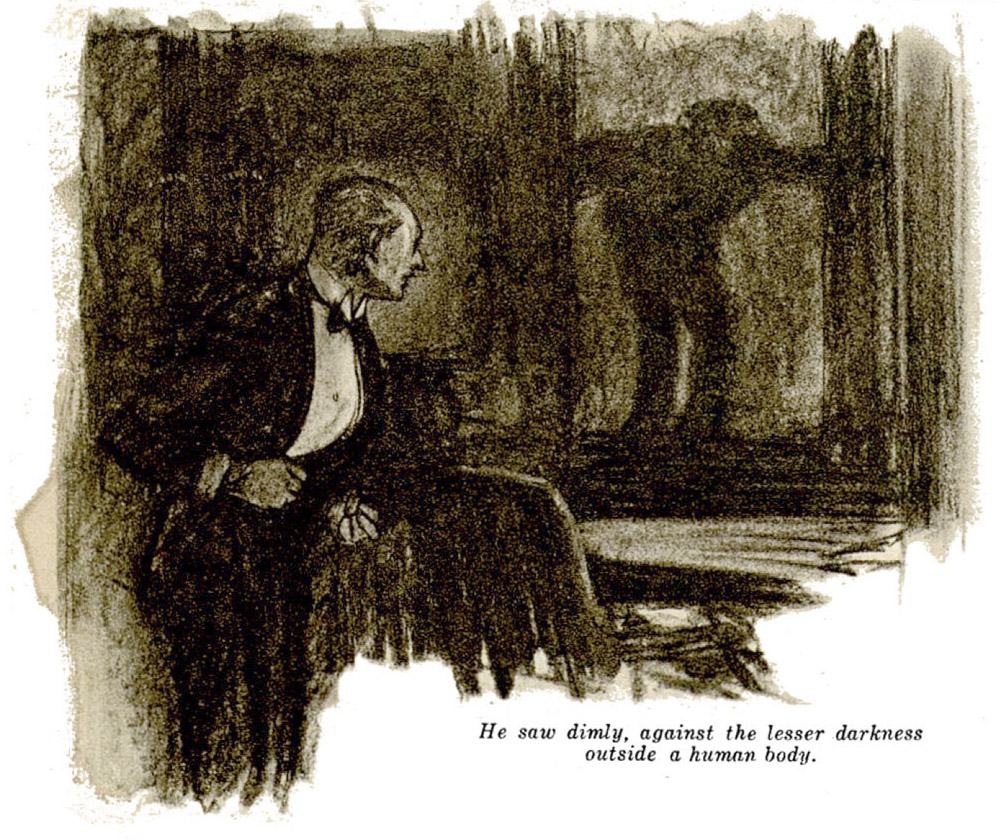

MR. TWIST was now definitely of the opinion that the gleam in the young man’s eyes was one of the most unpleasant and menacing things he had ever encountered. Transferring his gaze from this gleam to the other’s well knit frame, he decided that he was in the presence of one who, whether his singular request was due to weakness of intellect or to alcohol, had best be humored.

“Get on with it,” said Hugo.

He settled himself in a chair and lighted a cigarette. His whole manner was suggestive of the blasé nonchalance of a sultan about to be entertained by the court acrobat. But, though his bearing was nonchalant, that gleam was still in his eyes, and Chimp Twist hesitated no longer. He bent, as requested—and then, having bent, stretched.

For some moments he jerked his limbs painfully in this direction and in that, while Hugo, puffing smoke, surveyed him with languid appreciation.

“Now tie yourself into a reefer knot,” said Hugo.

Chimp gritted his teeth. A sorrow’s crown of sorrow is remembering happier things; and there came back to him the recollection of mornings when he had stood at his window and laughed heartily at the spectacle of his patients at Healthward Ho being hounded on to these very movements by the vigilant Sergeant Flannery.

How little he had supposed that there would ever come a time when he himself would be compelled to perform these exercises! And how little he had guessed at the hideous discomfort which they could cause a man who had let his body muscles grow stiff.

“Wait,” said Hugo suddenly.

Mr. Twist was glad to do so. He straightened himself, breathing heavily.

“Are you thinking beautiful thoughts?”

Chimp Twist gulped. “Yes,” he said, with a strong effort.

“Beautiful, tranquil thoughts?”

“Yes.”

“Then carry on.”

Chimp resumed his calisthenics. He was aching in every joint now, but into his discomfort there had shot a faint gleam of hope. Everything in this world has its drawbacks and its advantages.

With the drawbacks to his present situation he had instantly become acquainted; but now, at last, one advantage presented itself to his notice—the fact, to wit, that the staggerings and totterings inseparable from a performance of the kind with which he was entertaining his limited but critical audience had brought him very near to the open window.

“How are the thoughts?” asked Hugo. “Still beautiful?”

Chimp said they were, and he spoke sincerely. He had contrived to put a space of several feet between himself and his persecutor, and the window gaped invitingly almost at his side.

“Yours,” said Hugo, puffing smoke meditatively, “has been a very happy life, Twist. Day after day you have had the privilege of seeing my Uncle Lester doing just what you’re doing now, and it must have beaten a circus hollow. It’s funny enough even when you do it, and you haven’t anything like his personality and appeal. If you could see what a priceless ass you look, it would keep you giggling for weeks.

“I know!” said Hugo, receiving an inspiration. “Do the one where you touch your toes without bending the knees.”

In all human affairs the semblance of any given thing is bound to vary considerably with the point of view. To Chimp Twist, as he endeavored to comply with this request, it seemed incredible that what he was doing could strike anyone as humorous.

To Hugo, on the other hand, it appeared as if the entertainment had now reached its apex of wholesome fun.

As Mr. Twist’s purple face came up for the third time, he abandoned himself whole-heartedly to mirth. He rocked in his chair, and, rashly trying to inhale cigarette smoke at the same time, found himself suddenly overcome by a paroxysm of coughing.

It was the moment for which Chimp Twist had been waiting. There is, as Ronnie Fish would have observed in the village hall an hour or so earlier, if the audience had had the self-restraint to let him get as far as that, “a tide in the affairs of men, which, taken at the flood, leads on to fortune.”

CHIMP did not neglect the opportunity that fate had granted him. With an agile bound, he was at the window, and—rendered supple, no doubt, by his recent exercises—leaped smartly through it.

He descended heavily on the dog Emily. Emily, wandering out for a last stroll before turning in, had just paused beneath the window to investigate a smell which had been called to her attention on the gravel. She was trying to make up her mind whether it was rats or the ghost of a long lost bone, when the skies suddenly started raining heavy bodies on her.

Emily was a dog who, as a rule, took things as they came, her guiding motto in life being the old Horatian nil admirari; but she could lose her poise. She lost it now. A startled oath escaped her, and for a brief instant she was completely unequal to the situation.

In this instant Chimp, equally startled, but far too busy to stop, had disengaged himself and was vanishing into the darkness.

A moment later Hugo came through the window. His coughing fit had spent itself, and he was now in good voice again. He was shouting.

At once Emily became herself again. All her sporting blood stirred in answer to these shouts. She forgot her agony. Her sense of grievance left her. Recognizing Hugo, she saw all things clearly and realized in a flash that here at last was the burglar for whom she had been waiting ever since her conversation with that wire-haired terrier over at Webleigh Manor.

John had taken her to lunch there one day, and, fraternizing with the Webleigh dog under the table, she had immediately noticed in his manner something aloof and distinctly patronizing.

It had then come out in conversation that they had had a burglary at the Manor a couple of nights before, and the wire-haired terrier, according to his own story, had been the hero of the occasion.

He spoke with an ill assumed off-handedness of barking and biting and chasings in the night, and, though he did not say it in so many words, gave Emily plainly to understand that it took an unusual dog to grapple with such a situation, and that in a similar crisis she herself would inevitably be found wanting.

Ever since that day she had been longing for a chance to show her mettle, and now it had come. Calling instructions in a high voice, she raced for the bushes into which Chimp had disappeared.

Hugo, a bad third, brought up the rear of the procession.

CHIMP, meanwhile, had been combining with swift movement some very rapid thinking. Fortune had been with him in the first moments of this dash for safety; but now, he considered, it had abandoned him and he must trust to his native intelligence to see him through. He had not anticipated dogs. To a go-as-you-please race across country with Hugo he would have trusted himself, but Hugo in collaboration with a dog was another matter. It became now a question, not of speed, but of craft. And he looked about him, as he ran, for a hiding place, for some shelter from this canine and human storm which he had unwittingly aroused.

And fortune, changing sides again, smiled upon him once more. Emily, who had been coming nicely, attempted very injudiciously at this moment to take a short cut, and became involved in a bush. And Chimp, accelerating an always active brain, perceived a way out. There was a low stone wall immediately in front of him, and beyond it, as he came up, he saw the dull gleam of water.

It was not an ideal haven, but he was in no position to pick and choose. The interior of the tank from which the gardeners drew ammunition for their watering cans had, for one who from childhood had always disliked bathing, a singularly repellent air. Those dark, oily looking depths suggested the presence of frogs, newts, and other slimy things that work their way down a man’s back and behave clammily around his spine. But it was most certainly a place of refuge.

He looked over his shoulder. An agitated crackling of branches announced that Emily had not yet worked clear, and Hugo had apparently stopped to render first aid. With a silent shudder, Chimp stepped into the tank and, lowering himself into the depths, nestled behind a water lily.

He looked over his shoulder. An agitated crackling of branches announced that Emily had not yet worked clear, and Hugo had apparently stopped to render first aid. With a silent shudder, Chimp stepped into the tank and, lowering himself into the depths, nestled behind a water lily.

HUGO was finding the task of extricating Emily more difficult than he had anticipated. The bush was one of those thorny, adhesive bushes, and it twined itself lovingly in Emily’s hair.

Bad feeling began to arise, and the conversation took on an acrimonious tone.

“Stand still!” growled Hugo. “Stand still, you blighter dog.”

“Push,” retorted Emily. “Push, I tell you! Push, not pull. Don’t you realize that all the while we’re wasting time here that fellow’s getting away?”

“Don’t wriggle, confound you! How can I get you out if you keep wriggling?”

“Try a lift in an upward direction. No, that’s no good. Stop pushing, and pull. Pull, I tell you! Pull, not push. Now, when I say, ‘To you—’ ”

Something gave. Hugo staggered back. Emily sprang from his grasp. The chase was on again.

But now all the zest had gone out of it. The operations in the bush had occupied only a bare couple of minutes, but they had been enough to allow the quarry to vanish. He had completely disappeared.

Hugo, sitting on the wall of the tank and trying to recover his breath, watched Emily as she darted to and fro, inspecting paths and drawing shrubberies, and knew that he had failed.

It was a bitter moment, and he sat and smoked moodily. Presently even Emily gave the thing up. She came back to where Hugo sat, her tongue lolling and disgust written all over her expressive features.

There was a silence. Emily thought it was all Hugo’s fault; Hugo thought it was Emily’s. A stiffness had crept into their relations once again; and when at length Hugo, feeling a little more benevolent after three cigarettes, reached down and scratched Emily’s head, the latter drew away coldly.

“Dam’ fool!” she said.

Hugo started. Was it some sound, some distant stealthy footstep, that had caused his companion to speak? He stared into the night.

“Fathead!” said Emily. “Can’t even pull somebody out of a bush.”

She laughed mirthlessly; and Hugo, now keenly on the alert, rose from his seat and gazed this way and that. And then, moving softly away from him at the end of the path, he saw a dark figure.

Instantly Hugo Carmody became once more the man of action. With a stern shout, he dashed along the path. And he had not gone half a dozen feet when the ground seemed suddenly to give way under him.

This path, as he should have remembered, knowing the terrain as he did, was a terrace path, set high above the shrubberies below.

It was a simple enough matter to negotiate it in daylight and at a gentle stroll; but to race successfully along it in the dark required a Blondin. Hugo’s third stride took him well into the abyss. He clutched out desperately, grasped only cool Worcestershire night air, and then, rolling down the slope, struck his head with great violence against a tree which seemed to have been put there for the purpose.

When the sparks had cleared away and the firework exhibition was over, he rose painfully to his feet.

A voice was speaking from above—the voice of Ronald Overbury Fish.

“Hullo!” said the voice. “What’s up?”

WEIGHED down by the burden of his many sorrows, Ronnie Fish had come to this terrace path to be alone. Solitude was what he desired, and solitude was what he had supposed he had got until, abruptly, without any warning but a wild shout, the companion of his school and university days had suddenly dashed out from empty space and apparently attempted to commit suicide.

WEIGHED down by the burden of his many sorrows, Ronnie Fish had come to this terrace path to be alone. Solitude was what he desired, and solitude was what he had supposed he had got until, abruptly, without any warning but a wild shout, the companion of his school and university days had suddenly dashed out from empty space and apparently attempted to commit suicide.

Ronnie was surprised. Naturally, no fellow likes getting the bird at a village concert, but Hugo, he considered, in trying to kill himself was adopting extreme measures.

“What’s up?” he asked again.

Hugo was struggling dazedly up the bank.

“Was that you, Ronnie?”

“Was what me?”

“That.”

“Which?”

Hugo approached the matter from another angle.

“Did you see anyone?”

“When?”

“Just now. I thought I saw someone on the path. It must have been you.”

“It was. Why?”

“I thought it was somebody else.”

“Well, it wasn’t.”

“I know, but I thought it was.”

“Who did you think it was?”

“A fellow called Twist.”

“Twist?”

“Yes, Twist.”

“Why?”

“I’ve been chasing him.”

“Chasing Twist?”

“Yes. I caught him burgling the house.”

They had been walking along, and now reached a spot where the light, freed from overhanging branches, was stronger. Mr. Fish became aware that his friend had sustained injuries.

They had been walking along, and now reached a spot where the light, freed from overhanging branches, was stronger. Mr. Fish became aware that his friend had sustained injuries.

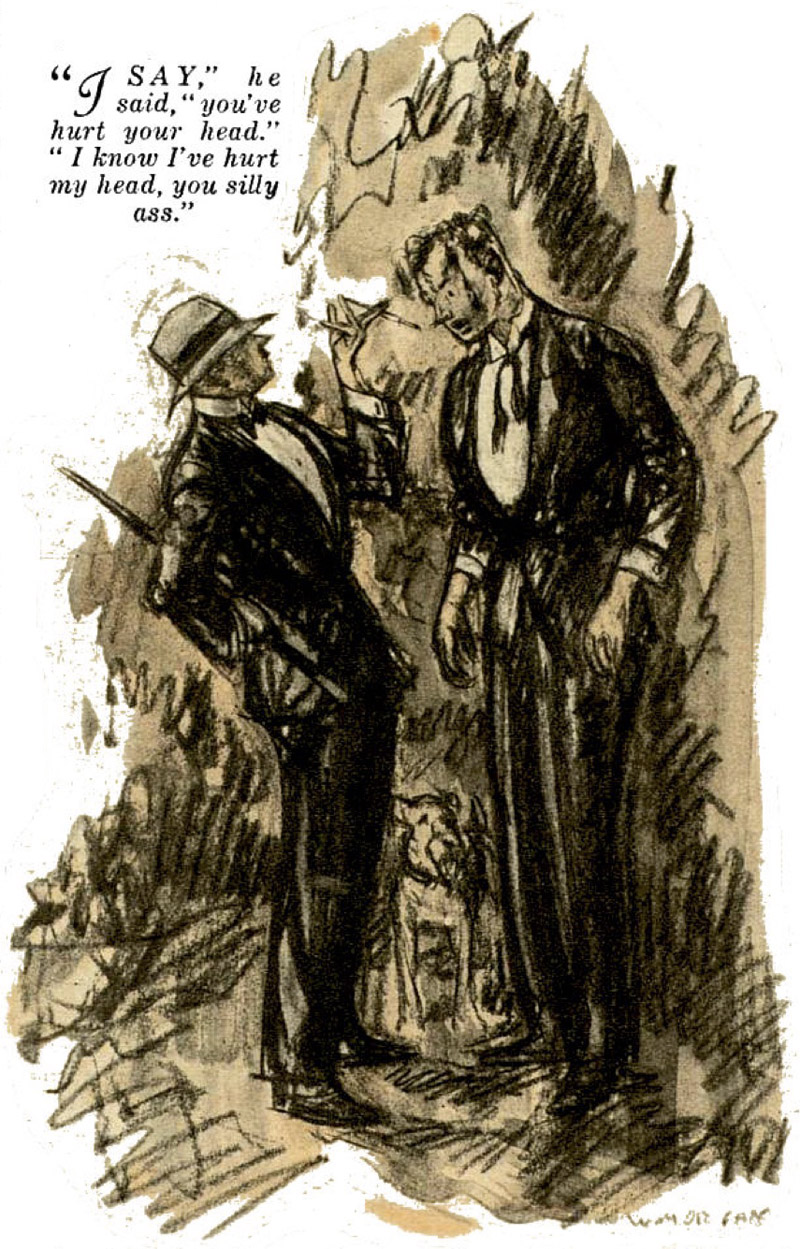

“I say,” he said, “you’ve hurt your head.”

“I know I’ve hurt my head, you silly ass.”

“It’s bleeding, I mean.”

“Bleeding?”

“Bleeding.”

HUGO put a hand to his wound, took it away again, inspected it.

“I’ll go and get old John to fix it,” he said. “He once put six stitches in a cow.”

“What cow?”

“One of the cows. I forget its name.”

“Where do we find this John?”

“He’s in his room over the stables.”

“Can you walk it all right?”

“Oh, yes, rather.”

Ronnie, relieved, lighted a cigarette, and approached an aspect of the affair which had been giving him food for thought.

“I say, Hugo, have you been having a few drinks or anything?”

“What do you mean?”

“Well, buzzing about the place after nonexistent burglars.”

“They weren’t nonexistent. I tell you, I caught this man Twist—”

“How do you know it was Twist?”

“I’ve met him.”

“Who? Twist?”

“Yes.”

“Where?”

“He runs a place called Healthward Ho near here.”

“What’s Healthward Ho?”

“It’s a place where fellows go to get fit. My uncle was there.”

“And Twist runs it?”

“Yes.”

“And you think this—dash it, this pillar of society was burgling the house?”

“I caught him, I tell you.”

“Who? Twist?”

“Yes.”

“Well, where is he, then?”

“I don’t know.”

“Listen, old man,” said Ronnie gently. “I think you’d better be pushing along and getting that bulb of yours repaired.”

He remained gazing after his friend, as he disappeared in the direction of the stable yard, with much concern. He hated to think of good old Hugo getting into a mental state like this—though, of course, it was only what you could expect if a man lived in the country all the time.

He was still brooding when he heard footsteps behind him, and looked round and saw Mr. Lester Carmody approaching.

Mr. Carmody gets first, a shock, then relief—then does something he had never done before in his life! Read about it in next week’s Liberty.

Madame Eulalie’s Rare Plums

Madame Eulalie’s Rare Plums