Liberty, August 4, 1928

Part Eight

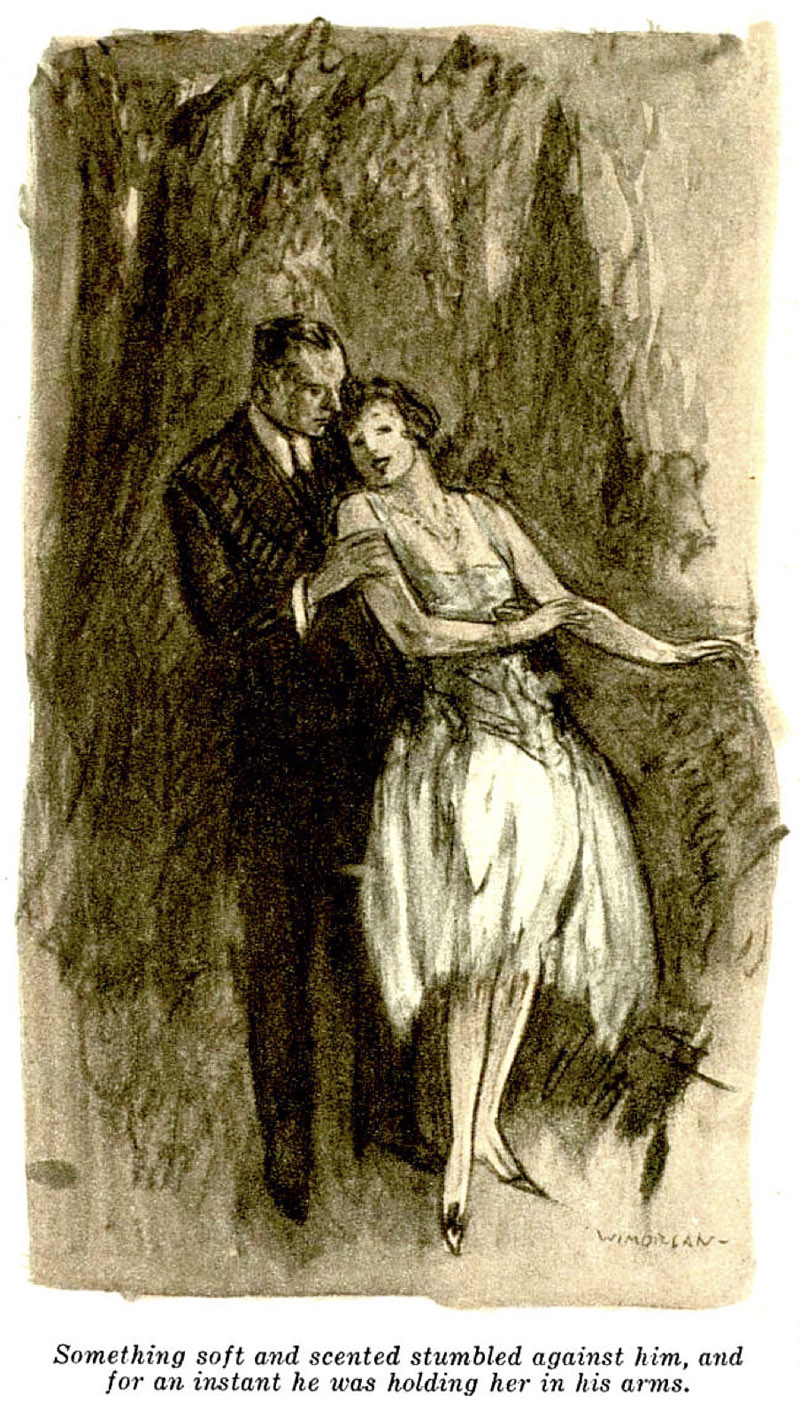

MR. CARMODY, lumbering along the dim path, was in a condition which in a slimmer man might have been called fluttering. He, like John, had absented himself from the festivities in the village, wishing to be on the spot when Dr. Twist made his entry into the house. He had seen Chimp get through the dining room window, and had instantly made his way to the front hall, purposing to wait there and see the precious suitcase duly deposited in the cupboard under the stairs. He had waited, but no Chimp had appeared. And then there had come to his ears barkings and shoutings and uproar in the night. Mr. Carmody, like Othello, was perplexed in the extreme. “Ah, Carmody,” said Ronnie Fish. He waved a kindly cigarette holder at his host. The latter regarded him with tense apprehension. Was his guest about to announce that Twist, caught in the act, was now under lock and key? For some reason or other, it was plain, Hugo and this unspeakable friend of his had returned at an unexpectedly early hour from the village, and Mr. Carmody feared the worst. Mr. Carmody gulped. “What—what—what—” “Poor old Hugo! Gone clean off his mental axis.” “What! What do you mean?” “I found him just now running round in circles and dashing his head against trees. He said he was chasing a burglar. Of course, there wasn’t anything of the sort on the premises. For, mark this, my dear Carmody: According to his statement, which I carefully checked, the burglar was a most respectable fellow named Twist, who runs a sort of health place near here. You know him, I believe?” “Slightly,” said Mr. Carmody. “Well, would a man in that position go about burgling houses? Pure delusion, of course!” Mr. Carmody breathed a deep sigh. “Undoubtedly,” he said. “Hugo was always weak-minded from a boy.” “By the way,” said Mr. Fish, “did you by any chance get up at five in the morning the other day and climb a ladder to look for swallows’ nests?” “Certainly not.” “I thought as much. Hugo said he saw you. Delusion again. The whole truth of the matter is, my dear Carmody, living in the country has begun to soften poor old Hugo’s brain. Take my tip and send him away to London at the earliest possible moment.” It was rare for Lester Carmody to feel gratitude for the advice which this young man gave so freely; but he was grateful now. He perceived clearly that a venture like the one on which he and his colleagues had embarked should never have been undertaken while the house was full of infernal, interfering young men. “Hugo was saying that you wished him to become your partner in some commercial enterprise,” he said. “A night club. The Hot Spot. Situated just off Bond Street, in the heart of London’s pleasure seeking area.” “You were going to give him a half share for five hundred pounds, I believe?” “Five hundred was the figure.” “He shall have a check immediately,” said Mr. Carmody. “And tomorrow you shall take him to London. The best trains are in the morning. I quite agree with you about his mental condition. I am very much obliged to you for drawing it to my notice.” “Don’t mention it, Carmody,” said Mr. Fish graciously. “Only too glad, my dear fellow. Always a pleasure, always a pleasure.” II JOHN had returned to his work, and was deep in it when Hugo and his wounded head crossed his threshold. He was startled and concerned. “Good heavens!” he cried. “What’s been happening?” “Fell down a bank and bumped the old lemon against a tree,” said Hugo, with the quiet pride of the man who has had an accident. “I looked in to see if you had got some glue or something to stick it up with.” John, as became one who thought nothing of putting stitches in cows, exhibited a cool efficiency. He bustled about, found water and cotton wool and iodine, and threw in sympathy as a makeweight. Only when the operation was completed did he give way to a natural curiosity. “How did it happen?” “Well, it started when I found that bounder Twist burgling the house.” “Twist?” “Yes, Twist. The Healthward Ho bird.” “You found Dr. Twist burgling the house?” “Yes; and I made him do bending and stretching exercises. And in the middle he legged it through the window, and Emily and I chivied him about the garden. Then he disappeared, and I saw him again at the end of that path above the shrubberies, and I dashed after him and took a toss—and it wasn’t Twist at all; it was Ronnie.” John forbore to ask further questions. This incoherent tale satisfied him that his cousin, if not delirious, was certainly on the borderland. He remembered the whole-heartedness with which Hugo had drowned his sorrows only a short while back in this very room, and he was satisfied that what the other needed was rest. “You’d better go to bed,” he said. “I think I’ve fixed you up pretty well, but perhaps you had better see the doctor tomorrow.” “Doc Twist?” “No, not Dr. Twist,” said John soothingly. “Dr. Bain, down in the village.” “Something ought to be done about the man Twist,” argued Hugo. “Somebody ought to pop it across him.” “If I were you I’d just forget all about Twist. Put him right out of your mind.” “But are we going to sit still and let perishers with waxed mustaches burgle the house whenever they feel inclined, and not do a thing to bring their gray hairs in sorrow to the grave?” “I shouldn’t worry about it if I were you. I’d just go off and have a nice, long sleep.” Hugo raised his eyebrows, and, finding that the process caused exquisite agony to his wounded head, quickly lowered them again. He looked at John with cold disapproval. “Oh?” he said. “Well, bung-oh, then!” “Good night.” “Give my love to the alpha separator and all the little separators.” “I will,” said John. He accompanied his cousin down the stairs and out into the stable yard. Having watched him move away, and feeling satisfied that he could reach the house without assistance, he was filling his pipe when Emily came round the corner. Emily was in great spirits. “Such larks!” said Emily. “One of those big nights. Burglars dashing to and fro, people falling over banks and butting their heads against trees, and everything bright and lively. But let me tell you something. A fellow like your cousin Hugo is no use whatever to a dog in any real emergency. He’s not a force. A broken reed. He—” “Stop that noise and get to bed,” said John. “Right ho,” said Emily. “You’ll be coming soon, I suppose?” She charged up the stairs, glad to get to her basket after a busy evening. John lighted his pipe and began to meditate. He found his mind turning to this extraordinary delusion of Hugo’s that he had caught Dr. Twist of Healthward Ho burgling the house. John had never met Dr. Twist, but he knew that he was the proprietor of a flourishing health cure establishment, and assumed him to be a reputable citizen. The idea that he had come all the way from Healthward Ho to burgle Rudge Hall was so bizarre that he could not imagine by what weird mental processes his cousin had been led to suppose that he had seen him. Footsteps sounded on the gravel, and he was aware of the subject of his thoughts returning. There was a dazed expression on Hugo’s face, and in his hand there fluttered a small oblong slip of paper. “John,” said Hugo, “look at this and tell me if you see what I see. Is it a check?” “Yes.” “For five hundred quid, made out to me and signed by Uncle Lester?” “Yes.” “THEN there is a Santa Claus!” said Hugo reverently. “John, old man, it’s absolutely uncanny. Directly I got into the house just now, Uncle Lester called me to his study, handed me this check, and told me I could go to London with Ronnie tomorrow and help him start that night club. You remember me telling you about Ronnie’s night club? Or did I? Well, anyway, he is starting a night club there, and he offered me a half share if I’d put up five hundred. By the way, Uncle Lester wants you to go to London tomorrow, too.” “Me! Why?” “I fancy he’s got the wind up a bit about this burglary business tonight. He said something about wanting you to go and see the insurance people—to bump up the insurance a trifle, I suppose. He’ll explain. But listen, John. It really is the most extraordinary thing, this. Uncle Lester starting to unbelt, I mean, and scattering money all over the place. I was absolutely right when I told Pat this morning—” “Have you seen Pat?” “Met her this morning on the bridge. And I said to her—” “Did she—er—ask after me?” “No.” “No?” said John hollowly. “Not that I remember. I brought your name into the talk and we had a few words about you, but I don’t recollect her asking after you.” Hugo laid a hand on his cousin’s arm. “It’s no use, John. Be a man! Forget her. Keep plugging away at that Molloy girl. I think you’re beginning to make an impression. I think she’s softening. I was watching her narrowly last night, and I fancied I saw a tender look in her eyes when they fell on you. I may have been mistaken, but that’s what I fancied. A sort of shy, filmy look. “I’ll tell you what it is, John. You’re much too modest. You underrate yourself. Keep steadily before you the fact that almost anybody can get married if they only plug away at it. Look at this man Bessemer, for instance—Ronnie’s man, that I told you about. As ugly a devil as you would wish to see outside the House of Commons, equipped with number sixteen feet and a face more like a walnut than anything. And yet, he has clicked. “The moral of which is that no one need ever lose hope. Consider the case of Bessemer. Compared with him, you are quite good looking. His ears alone—” “Good night,” said John. He knocked his pipe and turned to the stairs. Hugo thought his manner abrupt. III SERGEANT MAJOR FLANNERY, that able and conscientious man, walked briskly up the main staircase of Healthward Ho. Outside a door off the second landing, he stopped and knocked. A loud sneeze sounded from within. “Cub!” called a voice. Chimp Twist, propped up with pillows, was sitting in bed, swathed in a woolen dressing gown. His face was flushed, and he regarded his visitor from under swollen eyelids with a moroseness which would have wounded a more sensitive man. Sergeant Major Flannery stood six feet two in his boots; he had a round, shiny face at which it was agony for a sick man to look; and Chimp was aware that when he spoke it would be in a rolling, barrack square bellow which would go clean through him like a red-hot bullet through butter. “Well?” Chimp muttered thickly. HE broke off to sniff at a steaming jug which stood beside his bed, and the sergeant major, gazing down at him with the offensive superiority of a robust man in the presence of an invalid, fingered his waxed mustache. The action intensified Chimp’s dislike. From the first he had been jealous of that mustache. Until it had come into his life, he had always thought highly of his own fungoid growth; but one look at this rival exhibit had taken all the heart out of him. The thing was long and blond and bushy, and it shot heavenward into two glorious needle-point ends, a shining zareba of hair quite beyond the scope of any mere civilian. Non-army men may grow mustaches, and wax them and brood over them and be fond and proud of them; but, to obtain a waxed mustache in the deepest and holiest sense of the words, you have to be a sergeant major. “Oo-er!” said Mr. Flannery. “That’s a nasty cold you’ve got. A nasty, feverish cold,” proceeded the sergeant major, in the tones in which he had once been wont to request squads of recruits to number off from the right. “You ought to do something about that cold.” “I am doing subthig about it,” growled Chimp, having recourse to the jug once more. “I don’t mean sniffing at jugs, sir. You won’t do yourself no good sniffing at jugs, Mr. Twist. You want to go to the root of the matter, if you understand the expression. You want to attack it from the stummick. The stummick is the seat of the trouble. Get the stummick right and the rest follows natural.” “Wad do you wad?” “There’s some say quinine, and some say a drop of camphor on a lump of sugar, and some say cinnamon; but, you can take it from me, the best thing for a nasty, feverish cold in the head is taraxacum and hops. There is no occasion to damn my eyes, Mr. Twist. I am only trying to be ’elpful. You send out for some taraxacum and hops, and before you know where you are—” “Wad do you wad?” “I’m telling you. There’s a gentleman below—a gentleman who’s called,” said Sergeant Major Flannery, making his meaning clearer. “A gentleman,” being still more precise, “who’s called at the front door in a nortermobile. He wants to see you.” “Well, he can’t.” “Says his name’s Molloy.” “Molloy?” “That’s what he said,” replied Mr. Flannery. “Oh? All right. Send him up.” “Taraxacum and hops,” repeated the sergeant major, pausing at the door. He disappeared, and a few minutes later returned, ushering in Soapy. He left the two old friends together, and Soapy approached the bed with rather an awe-struck air. “You’ve got a cold,” he said. Chimp sniffed—twice: once with annoyance and once at the jug. “So would you have a code if you’d been sitting up to your neck in water for half an hour last night and had to ride home tweddy biles wriggig wet on a motorcycle.” “Says which?” exclaimed Soapy, astounded. Chimp related the saga of the previous night, touching disparagingly on Hugo and Emily. “And thad lets me out,” he concluded. “No, no!” “I’m through.” “Don’t say that.” “I do say thad.” “But, Chimpie, we’ve got it all fixed for you to get away with the stuff tonight.” Chimp stared at him incredulously. “Tonight? You thig I’m going out tonight, with this code of mine, to clibe through windows and be run off my legs by—” “But, Chimpie, there’s no danger of that, now. We’ve got everything set. That guy Hugo and his friend are going to London this morning, and so’s the other fellow. You won’t have a thing to do but walk in.” “Oh?” said Chimp. HE relapsed into silence, and took a thoughtful sniff at the jug. This information, he was bound to admit, did alter the complexion of affairs. But he was a business man. “Well, if I do agree to go out and risk exposing this nasty, feverish code of mine to the night air, which is the worst thig a man can do—ask any doctor—” “Chimpie!” cried Mr. Molloy in a stricken voice. His keen intuition told him what was coming. “I don’t do it on any sigsdy-forty basis. Sigsdy-five thirty-five is the figure.” Mr. Molloy had always been an eloquent man—without a natural turn for eloquence you cannot hope to traffic successfully in the baser varieties of oil stocks—but never had he touched the sublime heights of oratory to which he soared now. Nevertheless, when at the end of five minutes he paused for breath, he knew that he had failed to grip his audience. “Sigsdy-five thirty-five,” said Chimp firmly. “You need me, or you wouldn’t have brought me into this. If you could have worked the job by yourself, you’d never have tode me a word about it.” “I can’t work it by myself. I’ve got to have an alibi. I and the wife are going to a theater tonight in Birmingham.” “That’s what I’m saying. You can’t get alog without me. And that’s why it’s goig to be sigsdy-five thirty-five.” Mr. Molloy wandered to the window and looked hopelessly out over the garden. “Think what Dolly will say when I tell her,” he pleaded. Chimp replied ungallantly that Dolly and what she might say meant little in his life. Mr. Molloy groaned hollowly. “Well, I guess if that’s the way you feel—” Chimp assured him that it was. “Then I suppose that’s the way we’ll have to fix it.” “All right,” said Chimp. “Then I’ll be there somewheres about eleven, or a little later maybe. And you needn’t bother to leave any window opud this time. Just have a ladder laying around, and I’ll bust the window of the picture gallery where the stuff is. It’ll be more trouble, but I dode bide takig a bidder trouble to make thigs look more natural. You just see thad thad ladder’s where I can fide it, and then you can leave all the difficud part of it to me.” “Difficult!” “Difficud was what I said,” returned Chimp. “Suppose I trip over somethig id the dark? Suppose I slip on the stairs? Suppose the ladder breaks? Suppose that dog gets after me again? That dog’s not goig to London, is it? Well, then! Besides, considerig that I may quide ligely get pneumonia and pass in my checks— What did you say?” Mr. Molloy had not spoken. He had merely sighed wistfully. IV ALTHOUGH anxious thought for the comfort of his juniors was not habitually one of Lester Carmody’s outstanding qualities, in planning his nephew John’s expedition to London he had been considerateness itself. John, he urged, must on no account dream of trying to make the double journey in a single day. Let him have a good dinner in London, go to a theater, sleep comfortably at a first class hotel, and return at his leisure on the morrow. Nevertheless, in spite of his uncle’s solicitude, nightfall found John hurrying back into Worcestershire in the Widgeon Seven. He did not admit that he was nervous, yet there had undoubtedly come upon him something that resembled uneasiness. He had been thinking a good deal during his ride to London about the peculiar behavior of his cousin Hugo on the previous night. The supposition that Hugo had found Dr. Twist of Healthward Ho trying to burgle Rudge Hall was, of course, too absurd for consideration; but it did seem possible that he had surprised some sort of an attempt upon the house. Rambling and incoherent as his story had been, it had certainly appeared to rest upon that substratum of fact; and John had protested rather earnestly to his uncle against being sent to London on an errand which could have been put through much more simply by letter, at a time when burglars were in the neighborhood. Mr. Carmody had laughed at his apprehensions. It was most unlikely, he pointed out, that Hugo had ever seen a marauder at all. But, assuming that he had done so, and that he had surprised him and pursued him about the garden, was it reasonable to suppose that the man would return on the very next night? And if, finally, he did return, the mere absence of John would make very little difference. Unless he proposed to patrol the grounds all night, John, sleeping as he did over the stable yard, could not be of much help. And even without him Rudge Hall was scarcely in a state of defenselessness. Sturgis, the butler, it was true, must, on account of age and flat feet, be reckoned a noncombatant; but, apart from Mr. Carmody himself, the garrison, John must recollect, included the intrepid Thomas G. Molloy, a warrior at the very mention of whose name bad men in Western mining camps had in days gone by trembled like aspens. It was all very plausible; yet John, having completed his business in London, swallowed an early dinner and turned the head of the Widgeon Seven homeward. It is often the man with the smallest stake in a venture who has its interests most deeply at heart. His Uncle Lester John had always suspected of a complete lack of interest in the welfare of Rudge Hall; and as for Hugo, that urban-minded young man looked on the place as a sort of penitentiary. To John it was left to regard Rudge Hall in the right Carmody spirit—the spirit of that Nigel Carmody who had once held it for King Charles against the forces of the Commonwealth. Where the Hall was concerned, John was fussy. The thought of intruders treading its sacred floors appalled him. He urged the Widgeon Seven forward at its best speed, and reached Rudge as the clock over the stables was striking 11. The first thing that met his eye, as he turned in at the stable yard, was the door of the garage gaping widely open and empty space in the spot where the Dex-Mayo should have stood. He ran the two-seater in, switched off the engine and the lights, and, climbing down stiffly, proceeded to ponder over this phenomenon. The only explanation he could think of was that his uncle must have ordered the car out after dinner on an expedition of some kind. To Birmingham, probably. John thought he could guess what must have happened. He did not often read the Birmingham papers himself, but the Post came to the house every morning; and he seemed to see Miss Molloy, her appetite for entertainment whetted rather than satisfied by the village concert, finding in its columns the announcement that one of the musical comedies of her native land was playing at the Prince of Wales’. No doubt she had wheedled his uncle into taking her and her father over there, with the result that here the house was without anything in the shape of protection except butler Sturgis, who had been old when John was a boy. A wave of irritation passed over John. He had been looking forward to tumbling into bed without delay, and this meant that he must remain up and keep vigil till the party’s return. Well, at least he would rout Emily out of her slumbers. “Hullo?” said Emily sleepily, in answer to his whistle. “Yes?” “Come down,” called John. There was a scrambling on the stairs. “You back?” “Come along.” “What’s up? More larks?” “Don’t make such a beastly noise,” said John. “Do you know what time it is?” They walked out together, and proceeded to make a slow circle of the house. And gradually the magic of the night began to soften John’s annoyance. London had been stiflingly hot, and this sweet coolness was like balm. Emily had disappeared into the darkness—which probably meant that she would clump back up the stairs at 2 in the morning, having rolled in something unpleasant, and ruin his night’s repose by leaping on his chest. But he could not bring himself to worry about it. A sort of beatific peace was upon him. It was almost as though an inner voice were whispering to him that he was on the brink of some wonderful experience. And what experience the immediate future could hold, except the possible washing of Emily, he was unable to imagine. Moving at a leisurely pace, he worked round to the back of the house again, and stepped off the grass on to the gravel outside the stable yard. And, as his shoes grated in the warm silence, a splash of white suddenly appeared in the blackness before him. “Johnny?” He came back on his heels as if he had received a blow. It was the voice of Pat, sounding in the silence like moonlight made audible. “Is that you, Johnny?” John broke into a little run. His heart was jumping, and all the happiness which had been glowing inside him leaped up into a roaring flame. That mysterious premonition had meant something, after all. But he had never dreamed it could mean anything so wonderful as this. THE night was full of stars, but overhanging trees made the spot where they stood a little island of darkness in which all that was visible of Pat was a faint gleaming of white. John stared at her dumbly. Only once before in his life could he remember having felt as he felt now; and that was one raw November evening at school, at the close of the football match against Marlborough, when, after battling wearily through a long half hour to preserve the slenderest of all possible leads, he had heard the referee’s whistle sound through the rising mists, and had stood up, bruised and battered and covered with mud, to the realization that the game was over and won. He had had his moments since then, but never again till now had he felt that strange, almost awful, ecstasy. Pat, for her part, appeared composed. “That mongrel of yours is a nice sort of watchdog,” she said. “I’ve been flinging tons of gravel at your window and she hasn’t uttered a sound.” “Emily’s gone away somewhere.” “I hope she gets bitten by a rabbit,” said Pat. “I’m off that hound for life. I met her in the village a little while ago, and she practically cut me dead.” There was a pause. “Pat!” said John thickly. “I thought I’d come up and see how you were getting on. It was such a lovely night, I couldn’t go to bed. What were you doing, prowling round?” It suddenly came home to John that he was neglecting his vigil. The thought caused him no remorse whatever. A thousand burglars with a thousand jimmies could break into the Hall, and he would not stir a step to prevent them. “Oh, just walking.” “Were you surprised to see me?” “Yes.” “We don’t see much of each other nowadays.” “I didn’t know—I wasn’t sure you wanted to see me.” “Good gracious! What made you think that?” “I don’t know.” Silence fell upon them again. John was harassed by a growing consciousness that he was failing to prove himself worthy of this golden moment which the Fates had granted to him. Was this all he was capable of—stiff, halting, banal words? He saw himself for an instant as he must be appearing to a girl like Pat, a girl who had been everywhere and met all sorts of men—glib, dashing men; suave, ingratiating men; men of poise and savoir-faire who could carry themselves with a swagger. An aching humility swept over him. And yet, she had come here tonight to see him! The thought a little restored his self-respect, and he was trying desperately to discover some remark which would show his appreciation of that divine benevolence, when she spoke again. “Johnny, let’s go out on the moat.” JOHN’S heart was singing like one of the morning stars. The suggestion was not one which he would have made himself, for it would not have occurred to him; but, now that it had been made, he saw how superexcellent it was. He tried to say so, but words would not come to him. “You don’t seem very enthusiastic,” said Pat. “I suppose you think I ought to be at home and in bed?” “No.” “Perhaps you want to go to bed?” “No.” “Well, come on, then.” They walked in silence down the yew hedged path that led to the boathouse. The beauty of the night wrapped them about as in a garment. It was dark here, and even the gleam of white that was Pat had become indistinct. “Yes?” He heard her utter a little exclamation. Something soft and scented stumbled against him, and for an instant he was holding her in his arms. The next moment he had very properly released her again, and he heard her laugh. “Sorry,” said Pat. “I stumbled.” John did not reply. He was incapable of speech. That swift moment of contact had had the effect of clarifying his mental turmoil. Luminously now he perceived what was causing his lack of eloquence. It was the surging, choking desire to kiss Pat, to reach out and snatch her up in his arms and hold her there. He stopped abruptly. “What’s the matter?” “Nothing,” said John. Prudence, the kill-joy, had whispered in his ear, “Is it wise?” Before her whisper the cave man in John fled back into the dim past whence he had come. Most certainly, felt the twentieth century John, it would not be wise. Very clearly Pat had shown him, that night in London, that all that she could give him was friendship. He had read stories. In stories girls drew their breath in sharply and said, “Oh, why must you spoil everything like this?” He decided not to spoil everything. Walking warily, he reached the little gate that led to the boathouse steps, and opened it with something of a flourish. “Be careful,” he said. “What of?” said Pat. It seemed to John that she spoke a trifle flatly. “These steps are rather tricky.” “Oh?” said Pat. It wasn’t just the steps that were tricky! Fate had a whole bag of tricks up her sleeve. Watch them tumble out as the story leaps forward in next week’s installment. Printer’s errors corrected above:  “I’ve got a bit of bad news for you, Carmody,” said Mr. Fish. “Brace up, my dear fellow.”

“I’ve got a bit of bad news for you, Carmody,” said Mr. Fish. “Brace up, my dear fellow.”

“Johnny?”

“Johnny?”

Magazine had “its absolutely uncanny.”

Madame Eulalie’s Rare Plums

Madame Eulalie’s Rare Plums