French Leave

by

P. G. Wodehouse

Literary and Cultural References

This is part of an ongoing effort by the members of the Blandings Yahoo! Group to document references, allusions, quotations, etc. in the works of P. G. Wodehouse. These notes, a work in progress, are by Diego Seguí and Neil Midkiff, with contributions from others as noted below.

|

Preface (written for the 1974 edition) Chapter 1 Chapter 2 Chapter 3 Chapter 4 Chapter 5 Chapter 6 |

Chapter 7 Chapter 8 Chapter 9 Chapter 10 Chapter 11 Chapter 12 |

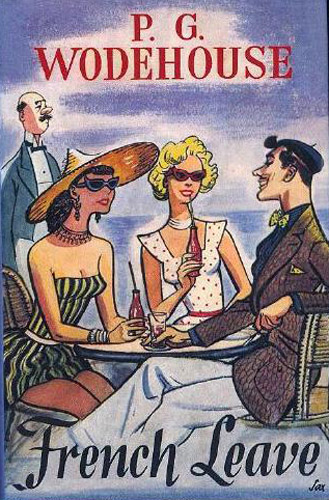

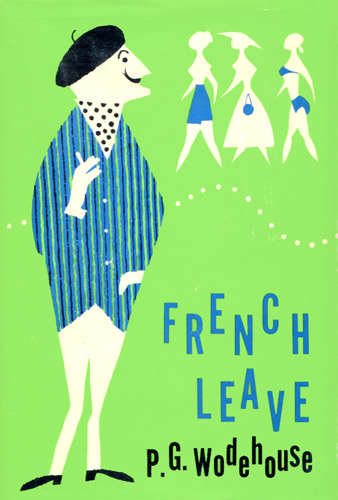

French Leave first appeared in a single-issue condensation in the Toronto Star Weekly, September 24, 1955, apparently based on an earlier stage of writing, with some differences in characters and plot elements. A four-part serial in John Bull, November 12 to December 3, 1955, is based on the UK text, but shortened with simple cuts. The UK first edition (left) was published by Herbert Jenkins, London, on January 20, 1956. It was reissued by Barrie and Jenkins in 1974 with a new preface by Wodehouse and with the text plates of the Jenkins first edition. The 1974 B&J edition was photo-reproduced for the 1992 Penguin paperback. Peter Schwed, Wodehouse’s editor at Simon & Schuster, didn’t like the novel on first reading in 1956 and, even when finally persuaded by its success in England, asked for some slight changes; the US book (right) was published by Simon & Schuster on 28 September 1959.

French Leave first appeared in a single-issue condensation in the Toronto Star Weekly, September 24, 1955, apparently based on an earlier stage of writing, with some differences in characters and plot elements. A four-part serial in John Bull, November 12 to December 3, 1955, is based on the UK text, but shortened with simple cuts. The UK first edition (left) was published by Herbert Jenkins, London, on January 20, 1956. It was reissued by Barrie and Jenkins in 1974 with a new preface by Wodehouse and with the text plates of the Jenkins first edition. The 1974 B&J edition was photo-reproduced for the 1992 Penguin paperback. Peter Schwed, Wodehouse’s editor at Simon & Schuster, didn’t like the novel on first reading in 1956 and, even when finally persuaded by its success in England, asked for some slight changes; the US book (right) was published by Simon & Schuster on 28 September 1959.

The basic idea of the girls-pretending-to-be-rich plot came from an unproduced musical, The Gibson Girls, written by Wodehouse and Guy Bolton, but not purchased by Florenz Ziegfeld. Guy Bolton turned it into a play Three Blind Mice (published under his pseudonym Stephen Powys), also the source of three Hollywood films: Three Blind Mice (1938, Twentieth Century-Fox); Moon Over Miami (1941, 20th Century-Fox); Three Little Girls in Blue (1946, 20th Century-Fox). Wodehouse shared his royalties on the book with Bolton for providing the core of the plot.

These notes are based on the UK edition, with occasional attention to some significant differences in the US book. Page references are to the UK editions (Jenkins 1956/B&J 1974/Penguin 1992). For users of other editions, a table of correspondences between the pagination of several available editions will open in a new browser window or tab upon clicking the link.

Preface (written for 1974 edition), pp. [5]–6

French leave

The phrase is cited as far back as 1741 in Green’s Dictionary of Slang, meaning to be absent from one’s work or military service without getting permission. Norman Murphy (A Wodehouse Handbook) notes that in French, the expression “aller à l’Anglais” (to take English leave) means the same thing.

I wrote it in 1956

Actually it must have been in 1955 or earlier; see details of magazine appearances in the introduction above.

settled in Remsenburg for several years

The Wodehouses had bought a home in Remsenburg, Long Island, New York in 1952.

Georges Courteling

Misprint for Courteline (1858–1929, born Georges Victor Marcel Molnaux), a French satirical novelist and playwright. Spelled correctly on next page of preface.

the normal grunts and gurgles of the foreigner who finds himself cornered by anything Gallic

Reminiscent of the famous opening line of The Luck of the Bodkins:

Into the face of the young man who sat on the terrace of the Hotel Magnifique at Cannes there had crept a look of furtive shame, the shifty, hangdog look which announces that an Englishman is about to talk French.

tooth and claw

See Chapter 8, below.

Valerir-Moberanne

Another 1974 preface misprint; it is Valerie-Moberanne in the UK text and Valérie-Moberanne, with acute accent, in the US book.

I don’t say he doesn’t owe something to Georges Courteline

In A Wodehouse Handbook, N. T. P. Murphy expressed his gratitude to Anne-Marie Chanet for detailing the extent of Wodehouse’s borrowing from Courteline, who was famous for ridiculing civil servants. She showed that the names of de la Hourmerie, Soupe, Letondu, Floche, Punez, and Boissonade came from Courteline’s plays and books, and that some of the Floche/Boissonade dialogue is a direct translation from a 1900 play by Courteline. More details of the borrowings are in Tony Ring’s Nothing Is Simple in Wodehouse.

Changing titles is an occupational disease with American publishers.

At least 23 of Wodehouse’s novels appeared under different titles in their US and UK book editions; see my page of information on the Wodehouse novels. It is possible, of course, that not all of these changes can be blamed on the American publishers.

Wodehouse had commented on the vagaries of publishers as early as 1907:

We are reminded of the question of book-titles by a letter from an authoress in a daily paper. She writes that the publisher, taking advantage of a clause in the agreement which gives him the power to do so, has substituted a title of his own for the one chosen by her. This opens up an appalling prospect for authors. A curate, let us say, publishes a collection of short addresses to young men which he has titled “The Narrow Path.” “No,” says the publisher, “not a selling title. Let me think.” A month later the papers are advertising “Wine, Women and Song.” Financially the author might profit. But we fancy it would not make him popular with his vicar.

“By Any Other Name” in Notes of the Day, Globe (London evening newspaper), March 21, 1907.

the Best Hundred Books Entitled French Leave

Wodehouse had made a similar joke in his preface to the UK edition (1929, Herbert Jenkins) of Summer Lightning:

I can only express the modest hope that this story will be considered of inclusion in the list of the Hundred Best Books Called Summer Lightning.

Chapter One

Bensonburg (p. 7)

A transparent pseudonym for Remsenburg, where Plum and Ethel Wodehouse lived at the time of writing.

a small farm at the bottom of one of the lanes that led down to the water (p. 7)

The Wodehouses lived on Basket Neck Lane, which does lead down to the water. Murphy, in A Wodehouse Handbook, confirmed that there were duck and chicken farms nearby as described.

The US book has “lead” rather than “led” here.

Brother Masons (p. 7)

Ian Michaud points out that Wodehouse himself was a freemason, joining in 1929 and submitting his resignation in November 1934.

Chanel Number Five (p. 7)

Despite the number in its name, this was the first perfume to come from Coco Chanel’s fashion house, in 1921. It remains popular today as a classic fragrance and, as here, its name can be used as an allusion to a glamorous and desirable scent.

taking after their mother (p. 8)

The Canadian newspaper version adds that she had been a model.

Kelly, Dubinsky, Wix, Weems, and Bassinger (p. 9)

Wodehouse seems to be using names with a wide variety of family backgrounds deliberately here, in the tradition of multi-ethnic platoons in Hollywood war movies. Henry seems to be the only Weems in Wodehouse, and this is the only Dubinsky, but elsewhere in Wodehouse there are seven Bassingers, three Kellys, three Wixes, and a Wix-Biffen. See Who’s Who in Wodehouse.

to dangle bars of gold before the eyes of the widow and the orphan (p. 9)

See Biblia Wodehousiana.

Palm Beach suit (p. 9)

Summer-weight dress clothing made from a fabric blended of cotton and mohair, invented in 1911 by a textile manufacturer, which set up the Palm Beach clothing company in 1931.

Smedley Cork wears Palm Beach suits in The Old Reliable, ch. 1 and 7 (1951); on the other hand, a failed ruse in Company for Henry, ch. 8.2 (1967) “should have stood out as plainly as a Palm Beach suit at the Eton and Harrow match”—implying inferiority to formal morningwear in the eyes of the traditionalist.

Come, Watson, the hunt is up (p. 9)

An echo of Sherlock Holmes, but not a direct quotation from Conan Doyle.

“Come, Watson, come!” he cried. “The game is afoot. Not a word! Into your clothes and come!”

“The Adventure of the Abbey Grange” (1904; in The Return of Sherlock Holmes, 1905).

on my way to Easthampton (p. 10)

Properly spelled East Hampton, the town is at the eastern end of the south shore of Long Island, some thirty miles east of Remsenburg/Bensonburg.

bit like serpents and stung like adders (p. 10)

See Biblia Wodehousiana.

blue bag (p. 10)

A small fabric bag containing a synthetic ultramarine blue dye and sodium bicarbonate, used traditionally in laundering white clothes to counteract any yellowing of the material. There are many online recollections of using a moistened blue bag as a soothing application for a bee sting, but so far no scientific explanation of why it works has been found.

res (p. 10)

Legal Latin for the matter at issue, the point under discussion.

that Thing and Thing thing in Bleak House (p. 10)

Dickens dealt with the grinding expenses of protracted litigation in his 1852 novel Bleak House, in which the Chancery case of Jarndyce and Jarndyce is concluded because the legal costs have used up the entire value of the disputed estate.

about thirty cents (p. 11)

Perhaps an echo of “feel like thirty cents”; see Cocktail Time.

two thousand dollars (p. 11)

In the 1959 US book, this amount is raised to three thousand dollars, and all references to four thousand of course become six thousand.

“Just about enough” (p. 11)

In the Canadian version only, there is a Shakespearean quotation here instead:

“It’s enough,” said Jo.

“ ’Twill serve,” said Terry.

See Shakespeare Quotations and Allusions in Wodehouse.

nest-egg (p. 11)

Henry uses the term in its financial sense, as a starting basis or reserve of money upon which to build by further labor and investment; the Trent sisters think first of the literal sense, an artificial egg (as of porcelain) left in a nest to induce a hen to lay more eggs there.

It appears as two unhyphenated words, nest egg, in both periodical appearances and in the US book.

invested in Government bonds … a mere pittance (p. 12)

US Treasury 10-year bonds bought in 1955, when this book was being written, averaged about 2.75 percent interest, so their combined $4,000 would yield $110 annually.

relict (p. 12)

An old-fashioned term for a widow or other survivor of a deceased person.

wildcat prospectus (p. 12)

This term would apply, for instance, to the inflated descriptions of the spurious oil-well shares sold by Soapy Molloy in several Wodehouse novels, or to any other investment promising more return than it can actually deliver.

governess (p. 12)

Thus in Canadian newspaper and UK book; omitted in UK magazine; “teacher” in US book. Same substitution or omission on the next page.

his plastic mind (p. 12)

Here “plastic” has its traditional meaning of easily molded, like a sculptor’s clay. This should be not be read in the chemical sense of an artificial polymer material like vinyl or polyethylene. Still less should one infer the modern pop-psychological sense of “insincere or artificial in emotional interactions”; that usage goes no further back than the 1960s.

sons of Belial (p. 13)

See Biblia Wodehousiana.

The Canadian newspaper version adds “He bestrode their little world like a colossus and his strength was as the strength of 10.” See Shakespeare Quotations and Allusions in Wodehouse and Uncle Fred in the Springtime.

corn before his sickle (p. 13)

And the ripe corn before his sickle fell

Among the jocund reapers.

William Wordsworth: The Excursion, book 7 (1814).

scrub your face with a soapy flannel (p. 14)

In US book, “a soapy washcloth.” Omitted from both periodical condensations.

St. Rocque on the Brittany coast (p. 14)

St. Rocque and the Festival of the Saint were introduced in Hot Water. In A Wodehouse Handbook, Norman Murphy nominates Dinard on the north coast of Brittany as the original of St. Rocque; Wodehouse himself holidayed there in 1922, and it is the only Breton location that fits the description of resort hotels and casinos.

the end of July (p. 14)

In Hot Water it was on July 15, and that is the date mentioned in the Canadian newspaper version.

Roville in Picardy (p. 14)

A transparent pseudonym for Deauville, a resort on the Channel coast northwest of Paris, near Trouville-sur-Mer, near where the Seine opens into the Channel, opposite Le Havre.

She’s hoping to marry a millionaire. (p. 15)

In the Canadian newspaper version only, both Jo and Terry seek to marry rich men; they describe their “investments” as “Wedding Bells Preferred” and “Orange Blossom Ordinaries.”

The new moon hung in the sky like a silver sickle (p. 17)

Wodehouse had used this image before:

Over to the west beyond the trees there still lingered a faint afterglow, and a new moon shone like a silver sickle above the big barn.

The Adventures of Sally, ch. 18 of book (1921/22)

…and Terry … bowed to it three times (p. 17)

So did Sally, following on from the previous quotation:

Sally came out of the house and bowed gravely three times for luck.

The Adventures of Sally, ch. 18 of book (1921/22)

Marquis de Maufringneuse … (p. 17)

Several of Wodehouse’s French characters have names that resemble ones in Balzac’s La Comédie humaine: the Duchesse de Maufrigneuse, the Marquis d’Esgrignon, the Princesse de Blamont-Chauvry. A Comtesse de Valérie-Moberanne appears briefly in The Triumphs of Eugène Valmont by Robert Barr [source: Wikipedia article on French Leave (novel)].

bonne-bouche (p. 17)

French for “good mouthful”: a tasty morsel or treat.

Chapter Two

the Bensonburg expeditionary force (p. 18)

When the United States entered World War One in 1917, the Army unit which fought on the Western Front, primarily in France, was called the American Expeditionary Force.

Rue Belleau … Rue Vanaye (p. 18)

Neither street name exists on modern maps.

Old Nick (p. 18)

Since at least 1643 this has been a familiar term for the Devil in literature.

Ministry de Dons et Legs (p. 18)

Only in the John Bull UK magazine serial is this office title fully in French as Ministère de Dons et Legs. It is unclear why Wodehouse’s other editors didn’t put the whole name into French. Wodehouse and his editors apparently expected readers to recognize Dons as “gifts.”

dwelt in marble halls with vassals and serfs at his side (p. 18)

An allusion to the aria “I Dreamt That I Dwelt in Marble Halls” from Balfe’s 1843 opera The Bohemian Girl, with lyrics by Alfred Bunn.

I dreamt that I dwelt in marble halls,

With vassals and serfs at my side,

And of all who assembled within those walls,

That I was the hope and the pride.

I had riches too great to count, could boast

Of a high ancestral name;

But I also dreamt, which pleased me most,

That you lov’d me still the same...

His only assets in the world today (p. 18)

The Canadian newspaper version adds just before this that his chateau in the Ardennes (mentioned in book versions in chapter 6.3) had gone, his racing stables and yacht had gone, and all but one of an ancestral collection of jewelled snuff boxes had gone.

mostly unpaid for (p. 18)

Many aristocrats, both in England and France, bought their clothing and other goods on credit, and some of them had the bad habit of paying late or never, considering that they sufficiently honored the tradesmen with their custom. It is also possible that some considered owing money to these suppliers was a point of pride, since in the days before credit cards or store charge accounts were available to nearly everyone, it was only the well-connected who were given the opportunity to delay paying for their purchases.

“I may be a chump, but it’s my boast that I don’t owe a penny to a single soul—not counting tradesmen, of course.”

Bicky Bickersteth in “Jeeves and the Hard-Boiled Egg” (1917)

Compare also Lord Peter Wimsey in Murder Must Advertise by Dorothy L. Sayers (1933), when pretending to be his own impecunious cousin Bredon, confronted by a fellow advertising writer with the accusation that his shoes are too expensive for his salary:

“…it is evident, dear lady, that you do not do your shopping in the true West End. You belong to the section of society that pays for what it buys. I revere, but do not imitate you.”

dossier Quibolle (p. 19)

By placing the proper name after the noun, Wodehouse accentuates the French feel of even his translated dialogue. Most adjectives and other modifiers in French are postpositive: le train bleu (the blue train).

sanctum (p. 20)

See Biblia Wodehousiana.

the right stuff (p. 21)

He roughed it in America for some years (p. 21)

Thus in Canadian newspaper and both US and UK books; this did not get changed when the timeline of Jefferson’s stay in America was altered for the US book (see ch. 5.3).

Mad as a hatter (p. 22)

See Uncle Fred in the Springtime.

bed-sitting-room (p. 26)

Thus in UK magazine and book. US book has “one-room apartment” here.

Just before his visit to his son, the Canadian newspaper version has a scene and characters not present in any later version. Old Nick takes his last snuffbox to the antique shop of Marcel Rapetaux in the Rue Faubourg St. Honore, selling it for ten thousand francs (“which sounds a lot but is actually about $30”). The dealer shows him a Renoir pastel of a young ballet dancer which he has made arrangements to purchase; the seller turns out to be the dancer herself, Juliette Buffard, now much aged, but once a star at the Moulin Rouge known as Julie-Bille-en-Bois, and an old friend of Old Nick, who explains that Rapetaux is offering her far too little (the same 10,000 francs) and that she could get much more from selling it elsewhere. He gives her the proceeds of his snuffbox on which to live until she can sell the pastel, and goes off to get money from his son.

Chapter Three

It was only in the last year or two… (p. 27)

The opening sentence of this chapter differs in the various version.

It was only in the last year or two that Old Nick had seen much of his son and heir, for almost immediately after his father’s second marriage the young man, disliking his stepmother—and Old Nick did not blame him—had removed himself from the family circle and gone to America, where he had supported himself in a fashion till the outbreak of the war.

UK book text. Canadian newspaper version is the same except for mistakenly omitting “last”.

It was only in the last year or two that Old Nick had seen much of his son and heir, for Jefferson had been in America until the outbreak of the war.

UK magazine, much abridged.

It was only in the last year or two that Old Nick had seen much of his son and heir, for almost immediately after his father’s second marriage the young man, disliking his stepmother—and Old Nick did not blame him—had removed himself from the family circle and gone to America, to his deceased mother’s family.

US book, emphasizing Jeff’s youth, in accordance with the statement later that Jeff had been only fourteen as a member of the French Resistance.

prodigal son (p. 27)

See Biblia Wodehousiana.

grey hairs in sorrow to the grave (p. 27)

See Biblia Wodehousiana.

Ridgfield, Connecticut (p. 27)

The US book correctly spells it Ridgefield, a real-life town founded some 300 years ago in the foothills of the Berkshire mountains. Both periodicals omit the description of Jeff’s mother’s family and the mention of this town.

the great race movements of the Middle Ages (p. 28)

[The] fresh swarm of British lecturers [to the USA in 1920] was like one of those great race movements of the Middle Ages.

Three Men and a Maid/The Girl on the Boat, ch. 1 (1921/22)

“No, that’s true. Well, I’ll be dashed. Did you know that I was once engaged to Florence?”

“Of course.”

“And now Stilton is.”

“Yes.”

“How absolutely extraordinary. It’s like one of those great race movements you read about.”

Joy in the Morning, ch. 6 (1946)

“We don’t want the thing to look like one of those great race movements.”

Uncle Dynamite, ch. 9.2 (1948)

[on New York theatrical writers going to Hollywood] Rudolf Friml was there and Vincent Youmans and Arthur Richman and a dozen more. It was like one of those great race movements of the middle ages.

Bring On the Girls, ch. 17.1 (1953)

“Odd how all these pillars of the home seem to be dashing away on toots these days. It’s like what Jeeves was telling me about the great race movements of the Middle Ages. Jeeves starts his holiday this morning.”

Jeeves in the Offing/How Right You Are, Jeeves, ch. 1 (1960)

“They’ve gone up to London.”

“So have Spode and Madeline. And Runkle ought to be leaving soon. It’s like one of those great race movements of the Middle Ages I used to read about at school.”

Much Obliged, Jeeves/Jeeves and the Tie that Binds, ch. 16 (1971)

rive gauche

The Left Bank of the Seine, the artistic quarter of Paris.

Chapter Four

Chapter Five

Chapter Six

Chapter Seven

Chapter Eight

tooth and claw

Usually the phrase refers to the savagery of wild beasts, as in “Nature red in tooth and claw” from Tennyson’s In Memoriam.

Chapter Nine

Chapter Ten

Chapter Eleven

Chapter Twelve

Wodehouse’s writings are copyright © Trustees of the Wodehouse Estate in most countries;

material published prior to 1931 is in USA public domain, used here with permission of the Estate.

Our editorial commentary and other added material are copyright

© 2012–2026 www.MadamEulalie.org.