Evening Despatch, Friday, 11 March, 1927.

Humorist’s Bath of Inspiration.

P. G. WODEHOUSE AFLOAT AT DROITWICH — THE MAN AND HIS WORK — TRIALS OF BEING FUNNY.

EXCLUSIVE TO THE “EVENING DESPATCH”

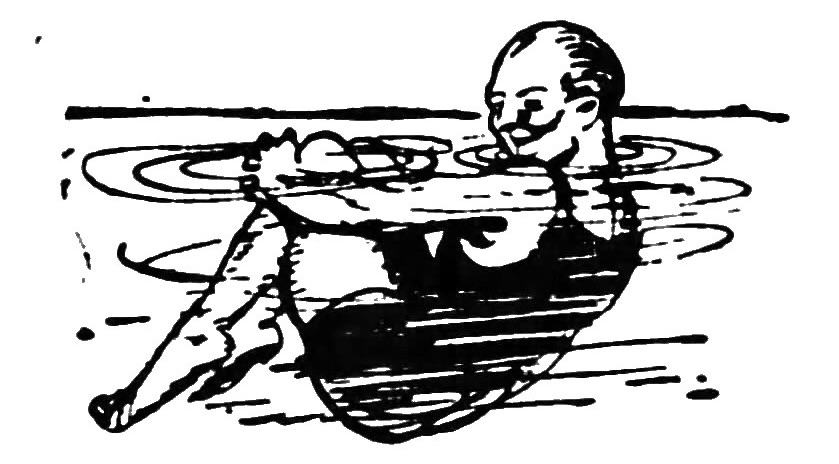

SHOULD you happen to see a large man floating round the big brine bath at Droitwich with his arms about his knees, looking rather like a huge white ball, that will be Mr. P. G. Wodehouse, the humorous writer who has made more laughter among the English-speaking peoples than any writer in the history of humorous literature.

The admirers of the work of Mr. Wodehouse—in Great Britain and America they total millions—will be glad to know that Mr. Wodehouse has not gone to the famous Worcestershire spa because of any stiffening of the joints of the fingers that tap his typewriter. He is there, so to speak, to treat the rheumatism of Mrs. Wodehouse. While Mrs. Wodehouse takes the private baths for her health, Mr. Wodehouse floats round the big public bath for pleasure and inspiration.

The admirers of the work of Mr. Wodehouse—in Great Britain and America they total millions—will be glad to know that Mr. Wodehouse has not gone to the famous Worcestershire spa because of any stiffening of the joints of the fingers that tap his typewriter. He is there, so to speak, to treat the rheumatism of Mrs. Wodehouse. While Mrs. Wodehouse takes the private baths for her health, Mr. Wodehouse floats round the big public bath for pleasure and inspiration.

“The brine water of that bath,” Mr. Wodehouse told me, “is the best I ever floated in. One can’t sink. In fact it’s so dense with salt that only half the body is in the water. In a way it’s hardly decent. But it’s a wonderful tonic. And being able to float round without effort rather appeals to me.”

Mr. Wodehouse confessed to me that the rapt gaze with which he floated round the brine bath was probably due to the fact that he is at present engaged upon a new novel which will almost certainly bear the characteristically Wodehouse title “John the Jellyfish.” Many of the scenes of this new novel will be laid in Worcestershire and Gloucestershire, and the characters will include those two American crooks—Twist and Molloy—who were responsible for so much of the humour in “Sam the Sudden,” the story which, it will be remembered, was serialised in the “Evening Despatch” some time ago.

Tradition Belied.

There is a tradition that the professional humorist is usually a melancholy man with a cadaverous countenance and a habit of contemplating suicide every now and then when inspiration fails him or is slow in coming. When I visited Mr. Wodehouse at the Impney Hotel, Droitwich—that magnificent mansion set in one of the most beautiful parks in England—I saw that tradition, in his case, lied. He is a large, comfortable-looking man with well covered bones. His humorous, mobile mouth would give to his face a look almost jovial if it were not that the usual expression in the bespectacled eyes is rather contemplative. He looks as if he could be as funny in conversation as he is on paper, and he can be.

I was half hoping that Mr. Wodehouse would chat to me in the picturesque slang of his famous dude characters—Archie Moffam and Bertie Wooster; that he would suggest a stab at a spot of billiards, or a stagger on to the golf course. But he spoke perfect English—English of a perfection which is only achieved by Englishmen who have spent half their life in America.

“Dude characters like Archie Moffam and Bertie Wooster have always fascinated me,” said Mr. Wodehouse. “No, I never met anybody quite like either of them. They are sheer inventions—types of moneyed irresponsibility. As a matter of fact, I have never drawn a single character from real life. And I believe that the character that is almost solely the product of invention is very often more realistic than the character drawn with photographic accuracy from real life. The nearest I ever got to the actual portrayal of a living man was in the creation of Psmith, of “Psmith, Journalist,” “Psmith in the City,” and the other Psmith tales. I never saw the original: I merely heard of him. Which is perhaps as well. There is nothing so devastating to the imagination as actual facts.”

The Idea—and then!

People who believe that written humour of the very high order to which Mr. Wodehouse has accustomed his readers is usually the product of the white heat of inspiration, will be interested to learn that Mr. Wodehouse is almost methodical in his working. “One must of course, get one’s idea,” said Mr. Wodehouse, “and that may come in a thousand ways from anywhere. But once the idea has come, the rest is a matter of concentration and application.” The first fifty pages of a novel would be hard work, and comparatively slowly typed; thereafter, however, the story would proceed at a rate of between two and three thousand words a day, typed in the mornings and the evenings.

Having regard to the difficulty of written humour even to a genius—and written humour is without doubt the most difficult department of the literary art—Mr. Wodehouse’s output is astounding. During the last few years his annual output has been two musical comedies, a “straight” play, a novel and 12 short stories. The straight play of last year, incidentally, has been described by the American critics who have seen it in New York as the most successful produced there since the war. It is shortly coming to this country, together with one or two of the musical comedies.

His Critic.

Mr. Wodehouse admitted that it was often very difficult for a writer of humour to tell whether his work was having a laughter-making effect on the reader. “The comic conception is born in the writer’s brain, and by the time he has got it down on paper it is stale to him. For him the element of surprise has gone, and he can never be sure that the written words convey the comic conception. I have always felt, therefore, that a writer of humour must have a critic on whose judgment he can rely. My critic is my daughter. I send nothing to a publisher of which she has not first approved.”

Mr. Wodehouse always types his stories. “When one really gets going,” he told me, “the pen can't keep pace with the ideas. At the same time I have never been able to adopt the speediest method of all of getting ideas on to paper—dictation. Dictating makes me feel as if I were a politician on a platform, and that feeling is fatal to story telling—strange as it may appear."

At his home in Norfolk-street, London, Mrs. Wodehouse constructed for her husband a delightful library, with book-lined walls, a wide desk, carpeted floors, and every convenience for the literary worker. Here Mrs. Wodehouse thought he shall work in comfort. Mr. Wodehouse actually uses, however, an attic bedroom which is equipped with a plain deal kitchen table, a chair, a gas stove and a typewriter. “During working hours,” he said, “I like a strictly businesslike atmosphere. Besides there are so many stairs to the attic that nobody ever climbs them to interrupt me.”

Greatest Trial.

Nobody has ever been more lyrical about the humours and trials of golf than Mr. Wodehouse. One would expect, consequently, that he spent all his spare time on a golf course. But he doesn’t. His favourite recreation is walking, and, according to Mrs. Wodehouse, getting his clothes into a deuce of a mess. The truth is that although Mr. Wodehouse has probed the heart of the average golfer deeper than any other writer, though he has extracted from the game more laughs than anyone else, he is not nowadays particularly keen on golf.

In fact, if one must be completely candid, he is capable of thinking of plots for stories while playing with out of bounds on the right and a cross-wind blowing from the left. Than which, of course, there is no greater heresy.

Mr. Wodehouse, naturally, smokes. He consumes each day an ounce of tobacco, described by Mrs. Wodehouse as being a mixture of cabbage and eau de Cologne. Recently “P. G.” fancied that he was smoking too much. Accordingly, he went to a doctor, who said, in effect: “Bo, cut it out. Nix on the smoke stuff. Three guineas. And come back on Tuesday.”

“P. G.”, intimidated, cut out the weed. But for one day only. Thereafter he cut out the doctor, his output for the smokeless day having been one word. It was the definite article “The,” beyond which he was unable to get.

“The great trial of having a reputation as a humorous writer,” said Mr. Wodehouse, “is that in private life people expect a man to be as funny as his books. The truth about humour is that it is rarely spontaneous. It is manufactured by blood and sweat. And when people expect me to talk like Archie Moffam or Bertie Wooster, or Psmith, or Jeeves—as they do—I begin to wish I had become a chartered accountant instead of a humorous writer. People who are introduced to a chartered accountant don’t expect him to present them with a balance sheet.”

Surprise for Wife.

Like most men whose work is creative, Mr. Wodehouse is inclined occasionally to be rather erratic. Once he was at Southampton, fresh from America and bound for London. He had put Mrs. Wodehouse into a carriage and had gone back down the train to see to the luggage. Suddenly, just as the train was starting, he appeared at the window of the carriage at which his wife was sitting. “Sorry,” he said, “but I shan’t be coming to London. I’ve just remembered old Jim’s within five miles of this place. Must see him. Take care of yourself. Cheerio.”

Mrs. Wodehouse did not see her husband for five days. She had no idea where he had gone. When he did turn up it appeared that he had bought a bicycle, visited several friends in the South-country, and then, in a day, cycled from Southampton to London—77 miles. He went to a hotel, and was shown the door because, after his exertions, he looked too much like a tramp. He got in at one of his clubs and rejoined Mrs. Wodehouse next morning.

“And where,” said Mrs. Wodehouse, “is the bicycle?”

“Outside the club,” said “P.G.” “I’ll get it.” But alas! the man of genius had been forestalled by the man of enterprise and the bicycle had gone.

Born Near Worcester.

To Midlanders it will be a source of pride that the birthplace of Mr. Wodehouse was Ham Hill, near Worcester. During the last few days he has visited the place for the first time since boyhood. He left Ham Hill to go to the well-known Dulwich School, connection with which he still maintains incidentally, by writing in the school magazine the reports of the school cricket matches. One of these cricket matches was a few years ago responsible for the loss to Mr. Wodehouse of many thousands of pounds. He had a wire from an American theatrical manager asking him to re-write a play. He preferred to attend the Dulwich School cricket match rather than catch the trans-Atlantic boat. That play earned for the man who did actually re-write it a small fortune.

Mr. and Mrs. Wodehouse are staying at the Impney Hotel, Droitwich, for six weeks. Next week they are being visited by Mr. Peter Haddon, the well-known actor, who is coming up from London to discuss the dramatisation of some of the Archie Moffam stories. Mr. Haddon has the idea that the Archie stories would make a very successful play, and he hopes himself to play the principal role.

. . . Inasmuch as, in the interests of the readers of the “Evening Despatch,” I have divulged the secret of the present haunt of England’s most popular humorist, I feel it incumbent upon me, in conclusion, to ask any reader who sees Mr. Wodehouse floating about the Droitwich brine bath not to splash the body. From what Mr. Wodehouse has told me of his next novel, it is going to be better than anything he has ever done, and, as one of those people to whom humorous literature is indispensable, I should hate anything to happen to that story. W.H.B.

From the Birmingham, England Evening Despatch, March 11, 1927.

Thanks to AK for finding the original of this article.

Notes:

Wodehouse often visited his grandmother Lydia Lea Wodehouse at Ham Hill in Worcestershire until her death in 1892, but he was born at Guildford in Surrey and lived for most of his early years in Bath.

“John the Jellyfish” was published in 1928 as Money for Nothing. Ian Michaud reminds us that in In Search of Blandings, Norman Murphy identified the Chateau Impney Hotel as the real-life model for Walsingford Hall, the home of Sir Buckstone Abbott in Summer Moonshine:

Ian Michaud reminds us that in In Search of Blandings, Norman Murphy identified the Chateau Impney Hotel as the real-life model for Walsingford Hall, the home of Sir Buckstone Abbott in Summer Moonshine:

a vast edifice constructed of glazed red brick, in some respects resembling a French château but, on the whole perhaps, having more the appearance of those model dwellings in which a certain number of working-class families are assured of a certain number of cubic feet of air. It had a huge leaden roof, tapering to a point and topped by a weathervane, and from one side of it, like some unpleasant growth, there protruded a large conservatory. There were also a dome and some minarets. Victorian villagers gazing up at it had named it Abbott’s Folly, and they had been about right.

Madame Eulalie’s Rare Plums

Madame Eulalie’s Rare Plums