Fred Patzel: Pavarotti of the Piglot

Norman Murphy’s sensational disclosure at our Houston convention [1999] that there existed a real Fred Patzel behind the “Pig-hoo-o-o-o-ey!” story has led to this almost equally sensational discovery by David Landman. As David mentioned in the fifth paragraph below, Col. Murphy commissioned other researchers to follow different lines in this quest. One such set of discoveries was made by Gary Hall and Linda Adam-Hall; their report is in the Winter 2000 issue of Plum Lines, page 8 and following.

A great voice as of a trumpet —Revelations

They are a crafty lot, these British brass hats. Tempered in kopjes and zarebas at the far-flung corners of Empire, they are past masters in the stealthy art of commando warfare. Deceptively cosmopolitan and suave, their silken manner conceals until too late the lightning strike of a cobra’s mailed fist. The reader will, of course, have recognized that I speak of Col. N.T.P. Murphy, Ret.

What follows is an account of my sandbagging last October by Col. Murphy whilst returning in a van from a visit to San Jacinto Battlefield outside Houston—and its perplexing outcome.

From the rear a buttery voice warbled, “I say, David, following my policy that everything in Wodehouse has a basis in fact, I note that James Belford, who, on the strength of his eponymous hog-call ‘Pig-hoo-o-o-o-ey!’ which stirs the languishing Empress to the trough when all else had failed and thereby wins Lord Emsworth’s approval of his marriage to his niece Angela, explains that he had his masterword ‘straight from the lips of Fred Patzel, the hog-calling champion of the Western States.’ It will come as no surprise to anyone, I am sure,” continued the voice, more marshmallowy than before, “that I know there really existed a Fred Patzel, but I can’t remember where I saw the reference. Do you think, dear fellow, that in an idle moment you could track him down?”

At least that’s what I think Col. Murphy said. One can never be sure. He might have been asking how it was possible the robust young blood he had seen in Boston four years earlier could have wizened so horribly in so short a time. I chose to credit the former likelihood.

“Righty-o,” I tossed back airily, hoping the others wouldn’t notice the gaff protruding from my gills. Murphy knew his man; the obsessive nature which made me as a boy so widely feared in scavenger races and Easter egg hunts would not let me rest until I had tracked the elusive Patzel to his lair. Nor did I suspect at the time that the vulpine Murphy had enlisted half a dozen other chumps in the same endeavor. That’s his method. He sits like a spider with a prodigious memory at the center of a vast web while a legion of operatives ferret about in the sub-basements of libraries feeding him information. Why, with a system like that, anyone could be The Man Who Knows Everything—unless it was a woman.

I will spare the reader an account of my daily agonies until six

months later, I finally ran Fred Patzel to ground just at the

library’s closing knell. The terror of those next few moments

still brings a cold sweat to the brow: the librarians, who had

already changed into stiletto heels, fish-net stockings and

leather mini-skirts and were eager to be moonlighting, straining

to drag me from the Xerox machine. I, in the gloomy knowledge

that if I was forced to return the journal to the circulation

desk uncopied, I would never see it again, simultaneously slotting

quarters and beating them off with my free hand. I got my copy,

and also, as I went bottom up down the marble steps to the pavement,

a painful demonstration of what ex

libris means

to the rowdier sort of librarian.

This is what I discovered. On 10 September 1926 the world awoke to news that the challenge issued by “Foghorn” Hughie Henry, the Kansas City Stockyards’ Goliath of the Gruntle, had been accepted by hog-callers of six states. Such titans as Swine-Songster Guy Bender, Baying Bob Warren, and Caruso of the Hog Belt Everett Dodd had thrown their cloth caps into the ring. But canny odds-makers knew that Hughie’s chief competition would come from the Champion of Nebraska, Fred Patzel (pronounced Pay-tzel). Had not Patzel’s prowess been featured in Ripley’s “Believe It or Not”: “Fred Patzel, champion hog-caller whose cry can be heard 5 miles”?

The contest was scheduled for September 11 (Super Trough Saturday) on neutral ground in Omaha. (Patzel stemmed from Madison.) The ground rules reflected how much hog-calling had been sophisticated in the Jazz Age: in the past, hog-calling contests had been held in the open where the winner was determined by the number of pigs that responded. This contest was to be held in the Omaha City Auditorium and broadcast to thousands glued to crystal sets the length and breadth of America’s heartland. As it was impractical to accommodate dozens of rooting hogs in a theatre, the snout-count method of scoring was abandoned. The contestants were to be judged on the subtler criteria of pitch and expression for a possible thirty points; resonance, worth an equal number of points; and honesty, sincerity, and heart appeal, which could gain twenty points. Volume, Patzel’s strength, was valued at a mere twenty points. Speculation ran wild. With lung power devalued, could Patzel muster the pathos and bonhommie to trump Hughie’s ace in the hole which was to enter the ring hungry, in the belief that only a hungry man can truly resonate with the inner being of a hungry hog?

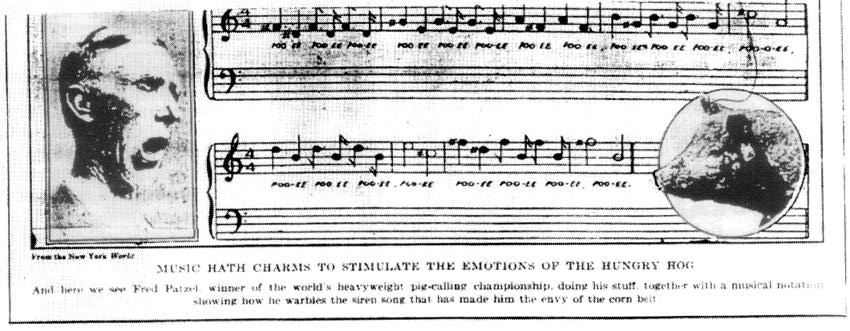

When the contest ended, for a brief moment all middle-America held its breath, which, upon reflection, was not unusual for aficionados at a hog-calling contest. Then the winner was announced. We can do no better than to quote the glowing words of the New York Sun: “Upon the laurels of Fred Patzel of Nebraska there is no taint of blight or mildew. Fred has been crowned champion hog caller of the universe in a contest open to all pretenders. His triumph was honestly won by the best man.” Fred Patzel reigned as hog-calling champion, not of the Western States as James Belford modestly claimed, but of the entire civilized universe! And here we should report that Patzel’s master-call was not “Pig-hoo-o-o-o-ey!” as Wodehouse would have it. The lyric Patzel wrote to what was said to be his own musical notation of his call was, “Poo-ee, poo-ee, poo-ee,” continuing the poo-ee motif unto the twentieth poo-ee.

Fred Patzel and his hog call, with musical notation said to be his

own, as printed in the Literary Digest of October 9, 1926.

There are a few incidental results of the contest which are worth reporting. Thomas M. Kilmartin of Griswold sued the city of Council Bluffs charging that one of his hogs leaped out of his truck and was killed when he heard Patzel’s call being rebroadcast. (Unfortunately, according to Donald Patzel, Fred’s son, no recording of his father’s call remains.) Guides in Anchorage, Alaska, spurred by the popularity of the Omaha contest, organized a Moose Calling Contest in which each contestant was obliged to provide himself with a regulation sized birch bark or corrugated cardboard horn through which to interpret the cry of a moose cow for her mate.

Fred Patzel wallowed in his success. He won a gold medal and seven hundred dollars, which, translated into current buying power, is about the cost of a Stealth bomber. With part of the money he bought an overcoat—reluctantly. “Never wore an overcoat in my life,” he protested, but Mrs. Patzel insisted. And fame brought with it privilege. Three days after his victory, Fred courted hubris by deliberately making an illegal U turn in his $25 snorting billy on Madison’s main street right in front of the town marshal by way of demonstrating his immunity from the law. The marshal endorsed Fred’s boast by standing at the curb grinning his approval, proud of the recognition accorded him by Fred’s cheery “Hello officer!” as he passed. The episode was reported in the local papers under the bold headline, “The Real Height of Fame: Fred Patzel Makes Horseshoe Turn in Middle of Street as Marshal Looks On.”

Fred Patzel and part of his family—note his medal. (Those 1926

photocopy machines were primitive.)

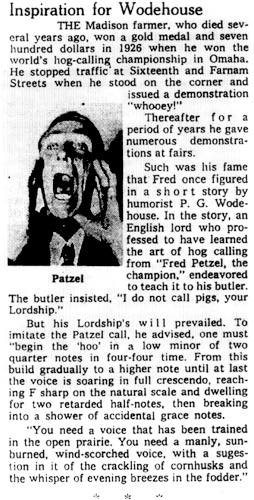

From Robert McMorris’s column in the

Omaha World-Herald

of February 7, 1967.

In 1927 Fred Patzel was immortalized in Wodehouse’s short story. In 1933 we have evidence his noble pipes had not thrown in the towel. Invited to demonstrate his call on a local radio station in Norfolk, Nebraska, “in order to give a little atmosphere to market reports,” he blew out more than $200 worth of tubes and put station WJAG off the air for three minutes. (This story was reported in Robert McMorris’ Omaha World-Herald column and confirmed by Fred Patzel’s son Donald in a recent telephone conversation.)

But, alas, fame is but for a season. By 1949 Fred was lamenting to an Omaha World-Herald columnist that “the art of hog calling” had vanished. And so had Fred’s renown. When in 1967 it was suggested that the new pork processing plant in Madison be named “Patzel’s Memorial Pork Packery” after the late champion, no one remembered his greater glory, and the plan was abandoned. Yet remembered he was. Ironically, it was as “the best darned ditch digger in all of Madison County"—an inferior, threadbare immortality at best. “No sewer ever ran backward if he dug the ditch,” gushed Blue Hill lawyer Ralph F. Baird. “And families were consoled with the thought that their dear ones lay straight, level and true in their perfectly sculpted graves.” Of Fred’s clarion call that could have passed for the doomsday trump and brought those dear ones running back to the bosoms of their families, not a mention.

No statue of Patzel graces the Madison city square, lamented Omaha World-Herald columnist Robert McMorris. We can only trust that there is a heaven reserved for porkers who have made the ultimate sacrifice for our morning rasher, and there, as the poet sings, “ ’midst warbling choirs of seraphic swine,” gleams a golden statue of Fred Patzel.

The reader will recall that I earlier wrote that my pursuit of the elusive Patzel had yielded a “perplexing” outcome. Reprinted here are the concluding paragraphs of an editorial that appeared in the New York Sun of September 14, 1926 and was later reprinted with other accounts of Fred’s triumph from New York and Boston newspapers in the Literary Digest of October 9, 1926. You are invited to compare them with the description of James Belford’s hog-call at the climax of “Pig-hoo-o-o-o-ey!”

He begins his ‘Poo-ey’ in a low minor of two

quarter notes in four-four time. From this he builds gradually

to a higher note, until at last his voice is soaring in full crescendo,

reaching F sharp on the natural scale and dwelling for two retarded

half notes, then breaking into a shower of accidental grace notes . . . the voice must be trained out on the open prairie with tornadoes

for sparring partners to give it robustness and strength. A manly,

sunburned, wind scorched voice is absolutely indispensable. . . it is a voice which should have within it a suggestion of

the crackling of corn husks, the whisper of evening breezes in

the fodder. Such vocal equipment belongs to Fred Patzel. That’s

why he is champion.

The perplexity is this: why would Wodehouse risk lifting such a prominent passage from the Sun’s beautifully written editorial as the climax of his story less than a year after the anonymous editorial and its reprinting in the Literary Digest if it was his intention to deceive? “Pig-hoo-o-o-o-ey!” first appeared in Liberty of July 9, 1927 and Strand Magazine the following month. And why did no one call him on the wholesale borrowing? Could it be that Wodehouse’s use of Fred Patzel’s name and the Sun’s perhaps celebrated description of his call was intended and taken by all concerned as an homage to the Orpheus of the hog-lot, the once and future champion of the universe, Fred Patzel?

—David Landman in Plum Lines, Summer 2000.

Madame Eulalie’s Rare Plums

Madame Eulalie’s Rare Plums