The Captain, May 1913

AFTER the rather gloomy meeting last year, when the coal strike was on everybody’s nerves, and half the schools did not compete, the 1913 boxing competitions, at the Queen’s Avenue Gymnasium, were refreshingly lively and well attended. There were two records. The number of entries was larger than ever before, and Clifton walked away with four championships—which feat even St. Paul’s has never accomplished. I am not sure that A. M. MacColl’s performance in the Bantams was not also a record. Last year, Ward, of Eton, went through three fights without having to complete a round of each. This year MacColl went one better by putting four opponents down and out, each in less than half a round.

Although

there was a full evening’s fighting on the Thursday, and a ten to one o’clock

session on the Friday, the main interest of the meeting began, as usual, at two

o’clock on the second day, when the stage had been cleared for the semi-finals

and finals. There was much good work done in the earlier bouts. Tatham

(Haileybury) put up a particularly plucky fight against Mothersill (Bedford).

Although

there was a full evening’s fighting on the Thursday, and a ten to one o’clock

session on the Friday, the main interest of the meeting began, as usual, at two

o’clock on the second day, when the stage had been cleared for the semi-finals

and finals. There was much good work done in the earlier bouts. Tatham

(Haileybury) put up a particularly plucky fight against Mothersill (Bedford).

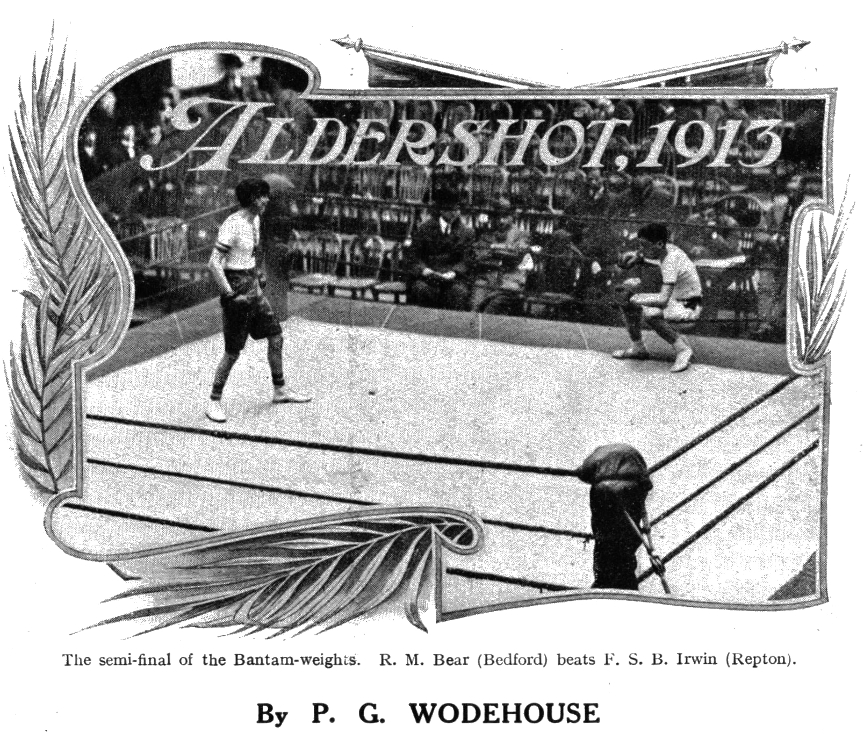

The semi-final of the Bantams found still surviving, besides the electrifying MacColl, Bear (Bedford), Irwin (Repton), and Earle (Tonbridge), who had had a tough bout with W. J. Armstrong (Worksop) in the second series.

The first pair were Bear and Irwin, and a splendid fight left the former in the final. After an even first round Bear’s strength began to tell. The second round was all his. In the third Irwin began to come back, but Bear had got too far ahead, and there was never doubt about the decision.

MacColl v.

Earle must have been about the most rapid thing on record. It is written in the

history of the American professional ring that a champion once met a would-be

champion somewhere out in Texas, and, having smitten him one blow, turned to

his seconds to have his gloves removed, with the remark, “I know what I done to

dat stiff.” Much the same happened now. MacColl shook hands, feinted with his

left, and shot in his right, and all was over. It was the only blow of the

contest.

MacColl v.

Earle must have been about the most rapid thing on record. It is written in the

history of the American professional ring that a champion once met a would-be

champion somewhere out in Texas, and, having smitten him one blow, turned to

his seconds to have his gloves removed, with the remark, “I know what I done to

dat stiff.” Much the same happened now. MacColl shook hands, feinted with his

left, and shot in his right, and all was over. It was the only blow of the

contest.

Personally, I hardly expected almost identically the same thing to happen in the final. Bear had a great advantage in height. MacColl is a midget, and for toughness Bear appeared to be a miniature edition of his brother, the middle-weight champion of a few years back. It did happen, however. The fight lasted less than forty seconds. A brief rally, and Clifton had won its first championship.

I cannot remember anything in all the Aldershot meetings I have attended which impressed me so much as MacColl’s cleverness, unless it was Erskine in the 1911 competitions. Nearly all the other bantam-weight fights were hard, even struggles, with the winner getting home ahead by a comparatively small margin of points. Yet MacColl “cleaned up” in about six punches all told. I was sitting right up against the ropes in the very corner where his little difficulty with Bear came to an end, and yet I could not see how it was done.

People

with whom, if I meet them, I shall refrain from quarrelling.—No.

1.: A. M. MacColl (Clifton).

People

with whom, if I meet them, I shall refrain from quarrelling.—No.

1.: A. M. MacColl (Clifton).

None of last year’s champions were defending their titles, but R. G. Ireland (Tonbridge), who won that amazingly vigorous bantam-weight final in 1912 against Farrell, of Cranbrook, had moved up into the Feathers, and was a strong favourite among bad judges of form—one of whom was the present writer. The excellences of Sheldon (Haileybury) did not dawn upon me till I saw him with Ireland in the semi-final. Even then Sheldon’s dreamy manner was deceptive. Ireland was all fire and energy. There were moments when he leaped in the air like a young gazelle (or grasshopper). Sheldon, on the other hand, wore a deprecating air. His eye was mild and introspective. He seemed to be trying to remember what it was they had asked him to be sure not to forget when he left Haileybury yesterday. Then, in the second round, he brightened up. It was all right. He had posted the letter. After that he was another man. He ducked, slipped, and worked his left like a professor. In the final round he unshipped a right hook, and Ireland went out.

Rees (Worksop), in the other semi-final, beat Rogers (St. Paul’s) after a good, even fight, in which the loser never gave up. Most of Rees’s points were won late in the last round.

The

final was excellent. Rees for a time looked like winning; but Sheldon’s

footwork was too good to let him do much damage; and after being a few points

behind on round one, the Haileybury representative went right ahead and won

well.

The

final was excellent. Rees for a time looked like winning; but Sheldon’s

footwork was too good to let him do much damage; and after being a few points

behind on round one, the Haileybury representative went right ahead and won

well.

If Sheldon is as young as he looks—he seems about fifteen—he should have a big future as a boxer. He is wonderfully cool, and has the straight left, the footwork, and all the other virtues.

Incidentally, Haileybury’s first championship, I believe. Or did they win the heavies once in the Dark Ages?

D. Wellesley-Smith (Dulwich), W. H. Shoobert (St. Paul’s), J. H. Cooper (Seaford

Engineering College), and C. A. B. Elliott (Clifton) were the Light-weight

semi-finalists. Of these Shoobert and Wellesley-Smith had shown the best form

in the opening bouts. They were drawn against each other in the semi-final; and

Wellesley-Smith, getting to work at once, was all over his man in the first

round. Shoobert seemed bewildered by the rapidity of the attack, and was down

three times before the first gong; but he rallied with great pluck in the last

round, and, though Wellesley-Smith never looked like losing, there was

excitement right up to the end. Elliott v. Cooper was a

tamer affair. Elliott is one of the most limited boxers that ever won a championship.

He has only one blow—a heavy right swing. As, however, he nearly always gets it

home, his limitations do not stand in his way very much. But he is not a pretty

boxer to watch. Owing to Elliott’s lack of variety, and Wellesley-Smith’s

inability to force the pace in the dashing manner he had adopted in earlier

bouts, the final was a little disappointing. Wellesley-Smith had the straight

left which should have stopped Elliott’s right swings, but, probably owing to

the pace of his semi-final, it had not enough force behind it. Still, on points,

the Dulwich man was ahead till the last round, when half a dozen right swings

wiped off his lead. The better boxer lost, but Elliott’s doggedness deserved

its reward.

D. Wellesley-Smith (Dulwich), W. H. Shoobert (St. Paul’s), J. H. Cooper (Seaford

Engineering College), and C. A. B. Elliott (Clifton) were the Light-weight

semi-finalists. Of these Shoobert and Wellesley-Smith had shown the best form

in the opening bouts. They were drawn against each other in the semi-final; and

Wellesley-Smith, getting to work at once, was all over his man in the first

round. Shoobert seemed bewildered by the rapidity of the attack, and was down

three times before the first gong; but he rallied with great pluck in the last

round, and, though Wellesley-Smith never looked like losing, there was

excitement right up to the end. Elliott v. Cooper was a

tamer affair. Elliott is one of the most limited boxers that ever won a championship.

He has only one blow—a heavy right swing. As, however, he nearly always gets it

home, his limitations do not stand in his way very much. But he is not a pretty

boxer to watch. Owing to Elliott’s lack of variety, and Wellesley-Smith’s

inability to force the pace in the dashing manner he had adopted in earlier

bouts, the final was a little disappointing. Wellesley-Smith had the straight

left which should have stopped Elliott’s right swings, but, probably owing to

the pace of his semi-final, it had not enough force behind it. Still, on points,

the Dulwich man was ahead till the last round, when half a dozen right swings

wiped off his lead. The better boxer lost, but Elliott’s doggedness deserved

its reward.

The

Welters, as they were expected to do on the form of the semi-finals, went to

Clifton. H. S. Kirkwood was the Clifton representative. In the semi-final he

beat Vacher (Sherborne) fairly easily; and in the final, with Anderton

(Repton), he was never in danger. Anderton had beaten Gavin (Haileybury) in the

semi-final. Gavin is a clever boxer, and there were many who thought the

decision should have gone to him. My own opinion was that Anderton was just

ahead at the end.

The

Welters, as they were expected to do on the form of the semi-finals, went to

Clifton. H. S. Kirkwood was the Clifton representative. In the semi-final he

beat Vacher (Sherborne) fairly easily; and in the final, with Anderton

(Repton), he was never in danger. Anderton had beaten Gavin (Haileybury) in the

semi-final. Gavin is a clever boxer, and there were many who thought the

decision should have gone to him. My own opinion was that Anderton was just

ahead at the end.

Kirkwood v. Anderton went the full three rounds, but the Clifton man’s quickness and the excellence of his footwork were too much for his opponent, and there was never a moment during the fight when Repton looked like spoiling Clifton’s record.

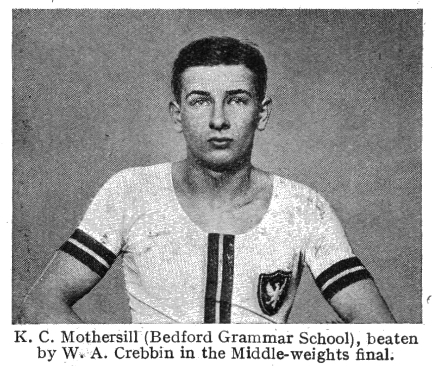

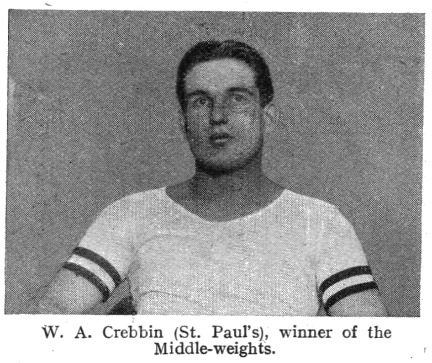

The Middle-weight final was quite like old times, being won by a typical St. Paul’s boxer, W. A. Crebbin. Last year Crebbin was the victim of a doubtful decision, but this year his luck was in, and he went safely over the full course. He had a very soft job in the semi-final, Waterton (Stonyhurst) being no match for him.

In the final Crebbin met Mothersill (Bedford), one of last year’s welters. Both were slow, but Crebbin was a good deal the stronger. Mothersill had had most of the energy taken out of him in his semi-final bout with Rossdale (Clifton). A very little luck might have given Clifton a fifth championship, for Mothersill’s win was a very narrow one.

Crebbin

has an ugly style, and Mothersill rather an attractive one; but Crebbin has the

Jerry Driscoll idea of perpetual aggressiveness, and he was always the man who

was doing the work. Mothersill stuck to him well, however, all through.

Crebbin

has an ugly style, and Mothersill rather an attractive one; but Crebbin has the

Jerry Driscoll idea of perpetual aggressiveness, and he was always the man who

was doing the work. Mothersill stuck to him well, however, all through.

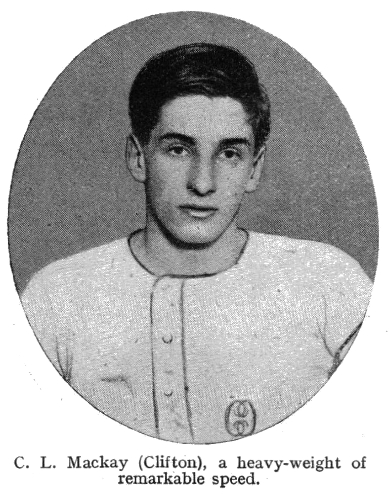

If it is true, as I saw in one of the papers, that C. L. Mackay, the Clifton heavy-weight, only started to learn boxing last term, he is by way of being a pugilistic marvel. He has all the mingled dash and coolness of a veteran. He gives the impression of knowing every move on the board. The lightest man in the catch-weight competition—his weight was given as 11st. 10lbs.—he went through in much the same way as MacColl in the bantams. In the first series he beat G. Pauling (Beaumont) in the first round. He next met Haymes (of Dulwich), and put him out in under a minute. In the semi-final Babington (Eton) kept him out till the last round, when the referee stopped the fight. And in the final, against Bunbury (St. Paul’s), the latter’s seconds threw up the sponge in the first minute.

Mackay has the speed of a middle-weight—in fact, considerably more speed than anyone exhibited in this year’s middle-weight competition. When he fills out he should be a remarkable boxer.

And so home, after one of the best Aldershots I remember.

Madame Eulalie’s Rare Plums

Madame Eulalie’s Rare Plums