The Captain, August 1904

I.

T was while playing

cricket that I saw Blenkinsop—for the first time for seven years. I was on tour

with the Weary Willies (that eminent club!), and a combination of circumstances

had brought us to a village in Somersetshire which you will not find on the

map. Our captain, a mere child in the art of tossing—which requires long and

constant practice before a man can become really proficient at it—called “Heads”

when it was perfectly obvious that the coin was going to come down tails, and,

the wicket being good, our opponents selfishly elected to take first knock.

T was while playing

cricket that I saw Blenkinsop—for the first time for seven years. I was on tour

with the Weary Willies (that eminent club!), and a combination of circumstances

had brought us to a village in Somersetshire which you will not find on the

map. Our captain, a mere child in the art of tossing—which requires long and

constant practice before a man can become really proficient at it—called “Heads”

when it was perfectly obvious that the coin was going to come down tails, and,

the wicket being good, our opponents selfishly elected to take first knock.

One of the first pair was Blenkinsop. I did not recognise him at first, but when he shaped to face my first ball—I was on at one end—his identity became certain. No two human beings in this vale of sorrow could stand like that. Blenkinsop’s batting attitude had once been the joy of his peers at Beckford, and the despair of the professional who looked after the junior cricket. He had much of the easy abandon of a cat in a strange garret—right leg well away from the bat, to facilitate flight towards the umpire in the event of a speedy yorker on the toes, left knee bent, body curved in a graceful arc over the handle of the bat. It was Blenkinsop all the way.

For old times’ sake I sent him down a long hop to leg. Any ordinary person would have put it joyfully out of the county. Blenkinsop was no ordinary person. He steered it very gently away for a single, and trotted up to my end.

“Hullo, Blenkinsop,” I said.

“Hullo!”

The progress of the game was interrupted for a few minutes, while he shook hands.

“Fancy seeing you!” he said; “Great Scott, why, it’s years since we met. Nearly ten. By Jove. I am glad to see you. Come round to my place after the match. I’m curate here, you know, and getting on splendidly.”

The batsman at the other end, who had been standing for some time in batting attitude, patiently waiting for the next ball, now gave the thing up, sat down with a resigned expression, and began to talk to the wicket-keeper. Mid-on lay down and apparently went to sleep, and short slip retired to the pavilion for one more gin and gingerbeer. These phenomena had not the slightest effect on Blenkinsop.

“What are you doing now?” he continued. “Have you seen any old Beckfordians lately? Do you remember——?”

Here mid-off asked the umpire to wake him if necessary, and lay down like his colleague on the leg-side. The voice of the Weary Willies’ captain, a slightly irascible person, made itself heard from the deep field, full of recriminations and enquiries. I thought I had better go on bowling, and did so. The next ball took a wicket, a fact which the batsman attributed audibly to the awful suspense in which he had been kept for the last five minutes, and I had leisure for some more Blenkinsopic conversation.

It was at this point that he asked me if I remembered his benefit.

“Do you remember Perkyn that night?” he said.

I did. Blenkinsop’s benefit stands out in my mind as the cheeriest memory of my school career. And there were some stirring episodes in that career. The affair of Mr. Stoker and the dog (which is “another story”) had caused me no little enjoyment. The episode of Tudway and the superannuated apple (I must tell you about that some time) had been not unamusing. But Blenkinsop’s benefit, in my humble opinion, defied competition.

The juniors of Jephson’s house were always rather a clannish lot. In my time we formed quite a close corporation. We walked together, and brewed together. We were most of us in the same form. I think now that they ought to have paid the master who took that form something extra, for his lot was certainly not cast in a pleasant place. There was Benson, for instance, a perfect prince of raggers, whose methods baffled detection, and Nicholas, second only to Benson. Perkyn, too, and Inge, and, indeed, all of us—we were all full of spirits.

Of this corporation Blenkinsop was a distinguished member. He had not the brilliance of a Benson, or the fertility of invention in the matter of excuses which characterised Inge, but he did his best, and showed clearly that he meant well. And there was no doubt that he was very popular with the rest of us.

It was with consternation, therefore, that we received the news one afternoon that at the end of term he was to leave us.

It appeared that Blenkinsop was to go for a couple of years to France, then to Germany for another year. Finally, if he survived this sentence, he would go up to Oxford, and become a clergyman. The idea of Blenkinsop as a clergyman had a marked effect on the company.

“But, look here, man,” said Benson, “you can’t leave. It’s rot. Why, who’s to umpire in the junior house-match next term if you go? We shall probably have to have Jephson!”

This was an awful thought. The sustained success of Jephson’s house junior team was largely due—and we recognised it—to the really magnificent umpiring of Blenkinsop. Blenkinsop’s was one of those beautifully emotional natures which cannot turn a deaf ear to an appeal for l.b.w. in the mouth of a friend. Alas! such natures are rare indeed, and Jephson’s was distinctly not one of them. There was once an umpire who claimed proudly that he never forgot which side he was umpiring for. Jephson was the exact antithesis of that conscientious sportsman.

“Besides,” said Inge, “you’re so young. What’s the good of leaving when you’re not fifteen yet? Why, if you stopped on, you might get your First.”

The idea of Blenkinsop figuring in the first eleven—unless they smuggled him in as an umpire—had the good effect of restoring the company to cheerfulness, and the conversation turned to less gloomy topics.

It was some days after this that I received a note in school. The bottom part of it had been freshly smeared with ink for the convenience of the reader, but I was up to this conventional pleasantry, and handled the letter with caution. It was short, and ran as follows:

Dear Sir,—Your presence is earnestly requested at a meeting of the Blenkinsop Benefit Society this evening at six sharp over the Gym.

We are, dear Sir,

Yours, &c.,

James Benson,

(Hon. Sec. B.B.Soc.)

P.S.—Don’t tell Blenkinsop about it as we want to keep it dark. Answer, R.S.V.P., if you please.

I replied that I would be there, and of the style and nature of the Blenkinsop Benefit Society I was soon made aware.

All our set, with the exception of Blenkinsop, had assembled at the gymnasium. Benson addressed the meeting.

“You see,” he said, “it’s awful rot about old Blenk leaving, and all that sort of thing, so I thought we might do something to testify—er—that is to—er——”

“To testify to our esteem?” I suggested.

“That’s the idea,” said Benson, gratefully, “—testify to our esteem.”

Nicholas wanted to know what was the exact meaning of the expression.

“Why, give him a send-off, of course, you idiot,” said Benson.

“Then why don’t you say so?”

“I think,” continued Benson, ignoring the interruption, “we ought to have a regular bust-up in his honour. We’ll put that to the vote. That this meeting approves of the proposal to give Blenkinsop a send-off. Ayes to the right, noes to the left.”

Everybody stood still, and Benson announced that the motion had been carried nem. con.

“Well, the next thing,” he went on, “is the tin. How are we going to manage about that?”

“Hang it all,” Inge protested, “you surely aren’t going to give him a set of silver tea-things, or anything of that sort?”

“No, what I was thinking of was a dormitory supper!”

Unrestrained applause on the part of the audience.

“But we aren’t all in Blenk’s dorm.,” said Smith.

“Doesn’t matter. You can buck out of your dorm. when the prefect’s asleep. Admission on presentation of a visiting-card.”

“That sounds all right. What time is the thing coming off?”

“We’d better have it the last Saturday of term. That’s a fortnight from to-morrow.”

“No, I mean what time?”

“Oh, about five o’clock I should think. That’ll be early enough.”

“Oh yes, rather.”

“It will be a scene of unrestrained revelry,” observed Benson, prophetically—a remark which elicited another objection, this time from Inge.

“How about Norris?” he asked.

Norris was the prefect who presided with an uncomfortably firm hand over the destinies of Blenkinsop’s dormitory.

“I thought of that,” he said, “ages ago. Norris’ people have just taken a house near Horton for the holidays, and he has got leave to spend the last week-end of term there. I was standing close by when he asked the Old Man.”

“But they may shove some one else in instead of him,” said Inge.

“They won’t. Or even if they do, it’ll only be Mainwaring, or somebody like that, who won’t mind what we get up to so long as we don’t make too much row about it. And, I say, there’s one thing we must remember. We must lie awfully low for the next fortnight, at any rate, in the dorm. The less we rag the less likely it is that anybody will be put into the dorm. when Norris is away. If they think that we can get on all right by ourselves, they’ll let us. See?”

We saw.

“That’s all right, then. Now, about the money again. How much can we raise?”

Money, as they say on ’Change, was rather tight. Towards the end of term one’s purse is never very heavy. There are so many things that one must buy; those luxuries, as somebody says, which are so much more necessary than necessities—buns at the quarter to eleven interval, potted meat for tea, and so on. However, in cash and promises of cash we managed to scrape together about six shillings, which Benson, who in addition to acting as secretary had modestly assumed the treasurership of the society, thought might almost be enough. And it was resolved that every member should write home and attempt, by specially representing himself on the verge of starvation, and compiling an excursus on the type of food we got at Jephson’s as a rule, to extract money from the parental coffers. This, said Benson, might or might not come off. If it did, we should have a Simple Beano (I quote his own classic expression). If not—well, we should have to get along as best we could with what we had already. A true philosopher, Benson.

Then somebody—Lucas, that was the man—made a brilliant suggestion.

“Look here,” he said, “if Norris is going to be away two nights, why not have two busts instead of one? Have the supper on the second night, and something in the assault-at-arms line on the first. We might get up a boxing comp., or something.”

Here Lucas, a passionate devotee of the Ring, shaped at an imaginary opponent, and delivered the left hook at the jaw with what would, in all probability, have been immense precision.

“Ripping,” said Benson. “That’s what we’ll do. Only we mustn’t have anything that’ll make too much row. Well, that’s all, I think. We might draw up some programmes in the meantime, and don’t you chaps forget to write to your people. Say grub will do if they can’t send money. Only money preferred, of course.”

“Of course,” we echoed as one man, and the meeting broke up.

II.

HE next fortnight was

dull. Very dull. Benson insisted on the members of the society lying low, with

a strictness worthy of Norris. The consequence was that we behaved in form, and

gave up stump cricket in the junior day-room, and in many other ways deprived

ourselves of much (more or less) innocent pleasure. The only one of us who

declined to alter his mode of life was Blenkinsop. He could not understand it

at all, and Benson refused to allow us to explain. He said it would be much

better to spring the great news suddenly on the favoured youth than to let him

know beforehand what honours the future had in store for him. So Blenkinsop

continued to be disorderly in a lonely, dazed sort of way, and complained

bitterly at intervals that the glory had departed from Jephson’s junior

day-room.

HE next fortnight was

dull. Very dull. Benson insisted on the members of the society lying low, with

a strictness worthy of Norris. The consequence was that we behaved in form, and

gave up stump cricket in the junior day-room, and in many other ways deprived

ourselves of much (more or less) innocent pleasure. The only one of us who

declined to alter his mode of life was Blenkinsop. He could not understand it

at all, and Benson refused to allow us to explain. He said it would be much

better to spring the great news suddenly on the favoured youth than to let him

know beforehand what honours the future had in store for him. So Blenkinsop

continued to be disorderly in a lonely, dazed sort of way, and complained

bitterly at intervals that the glory had departed from Jephson’s junior

day-room.

“I say,” he said to me one morning, “what on earth is the matter with you chaps? Why didn’t any of you back me up in math. this morning?”

“Oh, I don’t know,” I said, “one doesn’t always feel in form for ragging, somehow.” A revolutionary sentiment, which made Blenkinsop open his eyes and wonder what the world was coming to.

Meanwhile the preparations for the festivities went on apace. Inge managed to extract five shillings from an uncle, and an aunt of mine sent me one and six. After adding these and other subscriptions to the fund, Benson was able to announce officially that not only would there be enough for a Simple Beano, but it would also be possible to offer prizes in the preliminary assault-at-arms on the first night. Enthusiasm ran high at the news.

About a week before the date of the performance, the programmes were circulated. I still have one in my possession, very dirty and dog-eared, but still readable. It would be trespassing on the kindness of the reader to quote it in extenso. Suffice it to say that nearly every branch of sport was represented, from boxing to ping-pong, and that an elaborate menu of the banquet was embodied in it. This last was a distinct work of art, and a credit to Benson’s imaginative talents. It concluded with apt quotations from the works of Mr. W. S. Gilbert, a particular protégé of Benson’s, such as:

“Gentlemen, will you allow us to offer you a magnificent banquet?”

“Cut the satisfying sandwich, broach the exhilarating Marsala, and let us rejoice today if we never rejoice again.”

“Tell me, major, are you fond of toffee?”

“To-day he is not well.”

There were a good many more.

The spot event, so to speak, of the banquet would, according to the programme, be a case of pineapples—none of your tinned imitations, but real! Perkyn’s brother from the West Indies was sending them over. Perkyn had just received a letter from him, informing him that the case would arrive next week. Keen anxiety was felt as to whether it would come in time. The moment had now arrived when all should be revealed to Blenkinsop. Benson did it in a touching speech, in which he dwelt so long and fondly on the departing one’s sterling qualities, now as a ragger, now as an umpire, that that youth almost broke down. And when Benson reminded us how, against Leicester’s last year, he had given their two best men out l.b.w. and caught at the wicket in the first over, and so won us the match in the most handsome style, there was not a dry eye in the house.

“It’s awfully good of you chaps,” observed Blenkinsop, on being called on to reply, “and I tell you what.”

“What?” we asked.

“They’re having a house sing-song on Saturday evening, and as our dorm.’s the largest, they’re going to hold it there. If we have luck they may leave the piano in the room till the next morning, and if anybody can play, we might have a bit of a rag.”

Roars of applause, during which Nicholas owned up to being able to play some waltz tunes. This news plunged the meeting into a tremendous state of enthusiasm. Everybody liked waltz tunes, a few knew how to dance, and all were very certain that they were going to dance, whether they knew how to or not. It was agreed that the assault-at-arms, which would be over by—say—half-past six, should conclude with a grand concert. Could Nicholas play anything else? Rather. All sorts of things. Inge knew a comic song or two. I could play the bones. It was evident that the proceedings would not fall flat for lack of musical talent. The only thing was—would the piano be left? While we were still in doubt on this important point the case of pineapples arrived. It was a good, large case. We decided not to open it “till the night.”

The day came. The concert went off splendidly. We were always more or less in form at these sing-songs, and on this occasion I suppose we made as much noise as any dozen juniors of our weight and age in the kingdom could have done. It was an idiosyncracy of ours to make noise. We were of opinion that every one who wished to leave the world a brighter and happier place for his presence in it should adopt some speciality, and make himself a thorough master of it. Our speciality was noise. Benson’s prohibition of ragging was felt not to apply to an end of term dormitory concert. To prevent us enjoying ourselves at that would have been to have struck a deadly blow at the inalienable rights of the citizen. Such a blow we were determined to prevent, and Benson, seeing the force of our arguments, was wise enough to allow us to take our own way. We took it.

And the piano was left after all. Jephson and the prefects did think of moving it, but they decided not to.

It was about seven the next morning before proceedings recommenced. At that hour I awoke, with a hastily-formed impression that I was drowning, to find Nicholas, with every appearance of keen enjoyment, squeezing water into my mouth from a large and evidently very full sponge.

“Buck up,” he said, encouragingly, “we’re two hours late as it is.”

“Why, what’s the time?”

“Seven. And we ought to have begun at five. Come and help me get these chaps up.”

I seized my sponge, plunged it into the jug, and in less than two minutes the dormitory was awake.

Once begun, affairs marched rapidly. We cleared a space by moving the beds back along the walls, and opened the entertainment with a little football under Association rules. I am happy to say that I led my side to victory in a style that would have done credit to a captain of England. Three times in the first moiety did I put the sponge-bag under the chest of drawers, and twice after half-time did it hurtle from my toe and crash against the door. I have seldom played a finer game. We won by five goals to one, and the one was a fluke.

Lucas got the boxing, and the ping-pong—played on the floor with a tennis-ball and hair-brushes, a cricket-bag acting as a net—fell to Blenkinsop, a popular victory. In fact, everything went splendidly, until at seven-fifty, the purely athletic portion of the entertainment being over, we began on the music. That was fatal. Chapel at Beckford is at eight on Sunday mornings, and such were the ensnaring qualities of Nicholas’ playing—with the soft pedal down to minimise the volume of sound—that the bell rang while we were still at it, as if we had had the whole of the day before us. We stopped, and stared at one another blankly.

“I didn’t know it was half so late,” said Inge.

Benson rose to the occasion as usual.

“Well,” he said, “there’s one thing pretty certain, we can’t get to chapel in time. We’re bound to be too late to get in. So I votes we don’t try to. We can’t get into any worse row than we’re in at present. Forge ahead with the music, Nick.”

He turned to Inge with a brilliant smile.

“My dance, I think,” he said.

A couple of seconds later the ball was in progress once more. As I have had occasion to remark before, a true philosopher, Benson.

III.

INES,” said Inge, as

we left Jephson’s presence after a painful interview some two hours later, “are

the beastliest nuisance ever invented. And they don’t do you any good, either.

They only spoil your handwriting, and then you get more lines because they say

they can’t read your work.”

INES,” said Inge, as

we left Jephson’s presence after a painful interview some two hours later, “are

the beastliest nuisance ever invented. And they don’t do you any good, either.

They only spoil your handwriting, and then you get more lines because they say

they can’t read your work.”

Jephson, always the soul of generosity, had given us three hundred lines apiece for our morning’s manœuvres. If we so much as breathed during the remainder of the term, he had hinted, he should make a point of enlisting the crude but effective aid of the flagellum.

I think we would all have preferred such a course on this occasion. Jephson’s canes—the brown one particularly—stung like adders, but he rarely gave you more than six, and though a touching-up is undoubtedly painful while it lasts (and a little longer, perhaps), it is soon over. Whereas with lines—but the subject is too melancholy.

Inge had come particularly badly out of the business. The rest of us had received our sentence with quiet resignation. Inge, on the other hand, had perceived a chance of scoring off the Bench. “Please, sir,” he asked, “can I do mine out of Homer?”

“I shall be disappointed if you do not, Inge,” replied Jephson, politely. “With the accents, of course.” “Accents!” thought Inge, “what’s the man driving at?” Then in a flash he saw his hideous mistake. He had meant to say Horace, not Homer. Horace, sensible man, foreseeing that in some future century lines would be invented, turned out a certain quantity of his work in verses with about half a dozen syllables in them, a boon to the line writer. Homer, on the other hand, not only wrote in Greek, but wrote the longest possible lines he could. Three hundred lines of Homer are equivalent to about double the number of Vergil, the man one usually goes to for lines.

“I meant Horace, sir,” said Inge, hastily.

Jephson waved aside the suggestion.

“Homer will do equally well, Inge,” he said, and the interview terminated.

Benson took a more cheerful view of things. This may have been due to his dauntless spirit, or possibly the reflection that he had in his desk some eight hundred lines, written in odd moments and stocked against such a day as this, may have comforted him. He looked on the bright side.

“After all,” he said, “we haven’t got it nearly as hot as I thought we should have done. And there’s no doubt that we’re giving Blenk a ripping good send-off.”

There we admitted that he was right.

“All the same,” he continued, “perhaps under the circumstances we ought to run as few risks as possible till the end of term. If we’re late for chapel again there’ll be no end of a row. So I think, instead of having the supper at five to-morrow morning, we’d better have it at twelve to-night. Jephson will have finished his rounds by then, and there won’t be any danger if we don’t make a row. What do you chaps say?”

We were unanimously of the opinion that the sooner we got at the provisions the better. Our mouths had been watering for days.

So at the eerie hour mentioned, when churchyards yawn and graves give up their dead, we yawned and gave ourselves up to the pleasures of the palate.

Banquets are always pleasant things, says an authority, consisting as they do mostly of eating and drinking; but the specially nice thing about a banquet is that it comes when something’s over, and to-morrow seems a long way off, and there’s nothing more to worry about. Gazing upon the varied refreshments, we forgot the lines of to-day, and had no thought for what might happen when the remnants of the feast were discovered littering the floor on the morrow.

Benson had certainly laid out the Blenkinsop Benefit Society funds well in his capacity of treasurer. Without going into full details, I may touch lightly upon such items as sardines and chocolates éclairs, buns and potted turkey, consumed in the order given.

The pièce de resistance was the case of pineapples. It was a thrilling moment when Benson, with the rapt air of a high priest at some mystic ceremony, prised open the lid with a pair of scissors belonging to the absent Norris. There was an alarmingly loud crack as the lid came in half, but the noise had apparently not been heard outside the dormitory, for no Jephson broke in upon our revels.

A short struggle with the other half of the lid, in which Norris’ scissors suffered severely (Benson said thoughtfully that if we bent them back again he might not notice anything was wrong), and the way to the fruit was clear. There were six of the pineapples, beauties, all of them, and there were just a dozen of us. A rapid calculation revealed the fact that we should each get half of one. We shared them righteously, one to every two beds, and two to the four visitors from the other dormitories.

I was just dividing mine with Nicholas, when a curious thing happened.

Perkyn, who slept across the way, suddenly sprang up with a wild shriek, rushed to his jug, and plunged his left arm into it. It was now about twelve-thirty.

“Look here, young Perkyn!” said Benson, savagely.

“Ow! !” cried Perkyn.

“Shut up, you ass; do you want to wake the house?”

“I’m bitten!” shrilled Perkyn.

“You’re what?” cried Inge.

“Bitten. OW! ! !”

He danced painfully, still keeping his arm deep in the jug.

“Perhaps it’s only imagination,” suggested dear old Blenkinsop in his good, hopeful way.

Perkyn suspended his Terpsichorean exhibition to throw a piece of soap at the speaker.

The discussion might, and probably would, have been prolonged indefinitely, but for an interruption which switched our attention off Perkyn and his real or imaginary bites in a flash.

“Great Scott, you chaps,” cried Lucas, “look out. There’s a centipede! Look out, Nick, it’s coming towards you!”

And sure enough, there, on the floor, simply sprinting for Nicholas’ bed in a purposeful manner that seemed to say that, having done with Perkyn, it considered the time had come for the second course, was a genuine centipede. It was three feet long—no, I am allowing myself to be carried away in the enthusiasm of the moment. I scorn to palter with the truth. Subsequent inspection proved that it was only two and a half inches long. But still, even two and a half inches of centipede is quite enough for one dormitory, especially if one has neither shoe nor sock to protect one’s feet. The most grasping person will admit this.

I don’t think I have ever moved quicker than I did then. I jumped up in bed. My soap was reposing in its place. As the centipede passed over a patch of moonlight on the floor, I let fly. It was a superb shot.

Smack it went less than an inch in front of the beast’s nose. The happy result was that it slewed round, and scuttled, still with the same purposeful air, in the direction of Inge.

Inge was out of bed and on the floor—a position fraught with peril. He gave it a nail-brush at three yards range, and missed. He tried with the second barrel, a sponge, and missed again. The centipede was but a yard from him when he leaped on to Blenkinsop’s bed, and at the same moment Blenkinsop, that calm strategist, enveloped the reptile from above in a blanket.

It was the turning-point of the battle.

Up till now the centipede had ranged where it listed, a thing of fear. Now we had it in a corner, and proposed, wind and weather permitting, to show it exactly who was who, and precisely what was what.

Each armed with a trusty slipper, we surrounded the blanket, and waited for the enemy to show up. The minutes passed without a sign of it. Apparently the reptile found it warm and comfortable under the blanket, and meant to stay there.

“Now then,” said Lucas, in the language of the man on the touch-line, “have it out there, Beckford.” And it was rather like a football match. I felt just as if I was playing half behind a pack that wouldn’t heel. The suspense was something shocking.

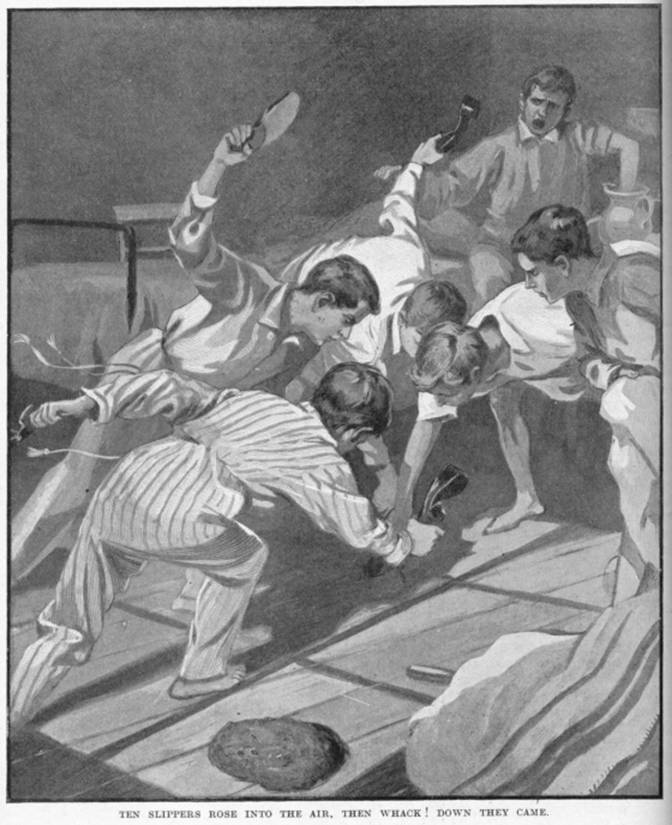

“Look here,” said Inge, after five minutes, “I’m going to switch the blanket off, and then you chaps go in hard with your slippers. Ready? Now then.”

For intense excitement the next minute beat anything I have ever experienced or wish to experience. We forgot what time it was and how vital it was to keep quiet, and egged each other on with shrill shouts. Perkyn, still with his arm in the jug, danced wildly, and impressed on us the necessity of bucking up.

Off went the blanket. Ten slippers rose into the air. Then whack! down they came, and from the centre of the inferno out scuttled the centipede, calm and unmoved as ever. Excitement ran higher.

“Beck-ford! !”

“Coming out your side, Nick.”

“Get to it, get to it.”

“Look out your end, Inge.”

“Coming over.”

Ten slippers crashed down again, and even as they crashed an icy voice spoke from the door.

“What is the meaning of this noise?”

We jumped up from where the late centipede lay flattened on the boards. At the door stood Jephson. He was simply but tastefully clad in pyjamas and a dressing-gown, and didn’t look a bit pleased at being woke up at one in the morning.

“Please, sir,” said Inge, “a centipede.”

“A what?”

Inge pointed to the corpse.

“Where did it come from ?”

“A case of pineapples, sir,” admitted Inge, reluctantly.

Jephson raised his candle and inspected the débris of the feast in silence.

“Has anybody been stung?” he asked at last.

“I have, sir,” said Perkyn.

“Then dress and go across to Dr. Fletcher’s.” Dr. Fletcher was the school doctor. He lived about a hundred yards from Jephson’s.

“And I should like to see you all in my study to-morrow,” he concluded, “directly after breakfast.”

“And after all,” said Benson, philosophically, on the following day, when Mr. Jephson had done with us, “I’d rather get touched up than more lines. And I think we may say we gave Blenk a fairly decent send-off.”

And the Blenkinsop Society, having admitted that his statements were justified, adjourned for light refreshments.

—————

Madame Eulalie’s Rare Plums

Madame Eulalie’s Rare Plums