The Captain, September 1906

ERRETT

junior said he wished he had a banjo. He went further. He said he wished

Merrett senior would give him one.

ERRETT

junior said he wished he had a banjo. He went further. He said he wished

Merrett senior would give him one.

“Do you know what banjos cost, Theodore?” inquired Merrett senior, who was in the City, and knew with a certain exactitude the value of money.

They were walking home from an afternoon concert when Merrett junior made his request. At the concert a man in a frock-coat and a yellow tie, a man, that is to say, entirely without claim to the respect of a right-thinking public, had dealt so dexterously with an instrument of the kind in question that Theodore’s vague yearnings for fame had swollen within him and crystallised. Hitherto he had wished to distinguish himself, without settling on any specific channel for his talents. He wanted to sit in an atmosphere of envy and congratulation, but he did not go so far as to say exactly how he proposed to do it. The concert weed’s rendering of “Dixie,” closely followed by “The Mosquitoes’ Parade,” had decided the matter. He would learn the banjo and play it to awed audiences when he got back to school. If a man in a frock-coat and yellow tie—bright yellow—could do it as well as that, how much better after earnest practice, couldn’t he do it? The general consensus of opinion at Seymour’s house, Wrykyn, of which house and school Merrett was a member, up to the present, was that he was a bit of an ass. His banjo would remove this impression.

The only objections were that he had not a banjo, and that his father, though a man of wealth, was not taking to the idea of giving him one with that jovial eagerness which ought to be the leading trait in a parent’s character.

“Do you know what these things cost, my boy?” asked Mr. Merrett, returning to his original suit.

“Yes. I know a place where you can get one for a quid. We’re just coming to it now. Look there!”

They stopped before a pawnbroker’s. In the window was an undeniable banjo, and the price, marked on a card in fair, round letters, was one pound.

“Well?” said Mr. Merrett, rattled.

“Shall I go in and order it?”

“Certainly not, certainly not. I shall give the matter a great deal more thought than I have had time to do up to the present before I buy you this instrument. Palmam qui meruit ferat, my boy. You must earn it, Theodore, you must earn it.”

Theodore’s reply was spoken under his breath, and escaped notice.

And so home.

On the following morning Merrett junior’s school report arrived. His father read it over his second cup of coffee. Coffee is supposed to have a soothing effect on the system. If this is so, we can only suppose that this was one of the beverage’s off-days. It seemed from this document that his form-work was poor. “Lacks energy and concentration,” wrote his form-master nastily, “without which qualities his undeniable talents avail him little.”

“This report is disgraceful,” said his father. “I see that the average age of boys in your form is fifteen. You are sixteen and a half. Your French, I note, is weak. How is that, when only last Summer you spent a fortnight with your Aunt Elizabeth at St. Malo?”

Theodore muttered something wordless through a jungle of toast and marmalade, and was asked not to speak with his mouth full.

The Serious Talk which was the sequel to the battle at breakfast ended in a sort of informal treaty. All was to be forgiven if Theodore should show a marked improvement during the forthcoming term. Meanwhile, for the remainder of the holidays, he would spend his mornings reading Greek and Latin authors on alternate days in order to give his Undeniable Talents a fair show. In the evenings, when he returned from business, Mr. Merrett would examine him on the day’s portion (with the help, though he did not mention this detail, of a Dr. Giles’ crib).

In this strenuous fashion the holidays drew to a close. By the time his boxes were packed, locked, and corded, and placed in the hall in readiness for the cab on the last afternoon, what Theodore did not know about the first three hundred lines of Euripides’ Medea and the first two books of Horace’s Odes was not knowledge. As for Merrett senior, he was beginning quite to enjoy those classics, and his opinion of Dr. Giles as an author was of the highest. On Theodore, on the other hand, the thought of those wasted mornings bore heavy. His air in the cab was one of gloom.

His father noted this melancholy, and not unnaturally set it down to grief at leaving the ancestral home. He was touched. When not impressed with the idea of doing his duty as a parent, Mr. Merrett was not a hard-hearted father. After all, he reflected, the boy had worked well for the last fortnight. He deserved some reward. (What the boy would have done if he had had a word to say in the matter, he did not ask himself.)

“Theodore, my boy,” he said, as they got out at the station, “I have come to a decision. Some time ago you mentioned a desire for a banjo.”

Sudden alertness on the part of Merrett junior.

“You shall have it.”

“Oh, thanks awfully.”

“If you bring back a prize with you at the beginning of the summer holidays.”

Return of dejected expression to the face of Theodore. What was the good of making a condition like that? What earthly chance had he of landing a prize? As regarded the form prize, he was in the position of a distant relative of a peer with a number of healthy lives between himself and the title. That trophy would fall to one of half a dozen or more Frightful Swots who were going up the school at a perfectly indecent pace. He had often felt that there ought to be some sort of a speed limit for this type of person.

He felt it again as the train moved on its way. The form prize was out of the question. Mathematics? He barred mathematics. Never had liked them. Couldn’t do a sum for nuts unless he consulted the Answers at the end of the book first. French? Ah, now what about French? What was the matter with that?

Two minutes later Theodore had decided to win the French prize.

It was Theo’s misfortune that in the same form as himself there happened to be one Tilbury. Now, Tilbury also wanted the French prize, and he meant to get it. The other members of the form had not the slightest desire even to see it. It happened therefore, that while thirty of the Lower Fifth entirely overlooked Merrett’s manœuvres, his thirty-first rival regarded them with the deepest suspicion and discontent. He confided his woes to Linton, that Lower Fifth ornament, during the interval one day. Linton was a cheery individual who rather led the Lower Fifth life and thought. He was promising at all games, and worked hard in form,—making up for this expenditure of effort by creating disturbances whenever possible.

“I say, Linton, I call it a bit thick,” said Tilbury.

“What is?” asked Linton.

“That bounder, Merrett,” explained Tilbury. “He’s given up full marks in French six times running.”

“Why shouldn’t he? Amuses him, and doesn’t hurt any one else.”

“But there’s the prize.”

“You don’t mean to tell me that you want it! I wouldn’t have it as a gift. If you’re so keen, your best dodge is to give up full marks, too.”

“Thanks. That’s a jolly good idea,” said Tilbury. “I will.”

(I do not defend Linton’s moral outlook. I merely record it.)

The system on which French was conducted at Wrykyn needs a little explanation. Etiquette did not demand honesty from you save in the examinations. At the end of the hour every one corrected his neighbour’s “slip,” and handed it back to him. The marks were then given up to M. Gandinois. Most people gave up something near full marks. It pleased M. Gandinois, and hurt nobody else. At the end of term the term’s marks were added to examination marks, and the winner got away with the prize. With Merrett, therefore, giving up full marks every time, it will be seen that Tilbury’s grievance was well-founded. Tilbury had not that wealth of imagination which is so necessary to success in French. He was in the habit of giving up only about 75 per cent. In the exams., of course, everybody played fair.

This was a curious point of French etiquette at Wrykyn. Cribbing might run riot during the term. In fact, the better you did it, the more of a sportsman you were considered. But by unwritten law it ceased absolutely as soon as the examination began. It had frequently puzzled M. Gandinois, the disastrous falling-off in the standard. Boys who had scored 95 per cent. throughout the term on questions of grammar, would amass totals of fifteen and twenty-one in the time of crisis. He put it down to brain-fag.

So Tilbury went his way, and proceeded to adopt a system of Retaliation. As for Merrett, he went on from strength to strength. Looking at his marks, the casual observer would have said that here was that rare prodigy, the English boy who was brilliant at French.

And in due course the end of the term came, bringing with it the examinations.

Tilbury came up to Linton as the Lower Fifth streamed out of the room, and foamed with indignation. His hands revolved in the air.

“Oh, chuck it,” said Linton; “you aren’t a semaphore. What’s up?”

“It’s that bounder, Merrett.”

“What’s he been doing to you’?”

“He was swindling. He swindled all the time. I saw him. I was watching him.”

Linton looked serious.

“Are you certain?” he said.

“Absolutely. I was watching him. I saw him. He had a book under the desk. Old Gandinois couldn’t see him because the top of his desk was in the light, but I could. I was watching him. And now he’ll get the prize.”

“Don’t you worry. He hasn’t got it yet,” said Linton. “Look here, did any one else see him?”

“I don’t know. Firmin might have done. He was sitting near him.”

“All right. I’ll ask Firmin. And don’t go gassing about it till you hear from me, or you’ll go getting into trouble. See!”

Tilbury saw.

Linton consulted Firmin. Firmin supported Tilbury.

“Yes, he’d certainly got a book under the desk. Rather rot, I call it, even in French. Not that one wants the prize, of course,” he added hastily, lest he should be misjudged.

“Of course not. Still——”

“In an exam.——” said Firmin.

“It’s not quite——”

“The game, is it?”

“Better not say anything to anybody, Firmin. I’ll look after this.”

That night Merrett wrote to his father. He was, he said, in excellent health, and hoped his father was the same. He added that he had hopes of bringing back the French prize.

And when at the prize-giving, two days later, the headmaster read out, without excitement (for he was beginning to get a little tired of the business), “French prize, Lower Fifth,—T. Merrett,” these hopes would have appeared to the majority of people to have been realised. As Merrett walked down the hall with his handsomely bound copy of “Les Misérables” in his hand, he saw himself, as in a vision, playing “Lumberin’ Luke” to enthusiastic audiences.

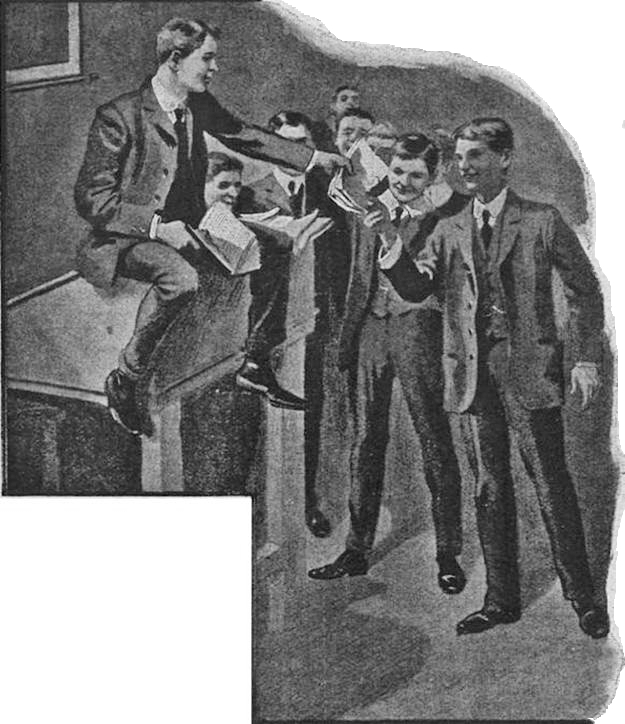

The Lower Fifth had assembled in force in their form-room to collect their books when Merrett arrived. Linton was standing by the master’s desk. He seemed to be waiting for something.

“Hullo, Merrett,” he said. “Is that the prize? Let’s have a look.”

Possessing himself of the gleaming volume, he cleared a space for himself among the ink pots and papers on the desk, and sat down. Merrett noticed that a certain hush of expectancy had fallen on the room.

“Look here, Merrett,” said Linton, turning over the leaves of the book, “you probably don’t know it, but you were seen cribbing the exam. What about that?”

“Fat lot of right you’ve got to talk about cribbing,” said Merrett.

“We all crib during the term, so it’s all right. But it’s an understood thing that we don’t do it during exams. So you don’t seem to have much claim to this rotten book, do you?”

“Give it back.”

“Wait a second. You’ll get your share all right. This is going to be done perfectly fairly. Now, some forms would have touched you up for this, wouldn’t they, you chaps?”

“Rather,” said the form.

“But we aren’t going to. You ought to be grateful. Only, as we’ve all got just as much right to the prize as you, we’re going to divide it.”

“I say—” said a voice of protest. Tilbury had come out second in the French order, and he had not looked for this Communistic arrangement.

“Dry up,” said Linton. “And if you come any nearer, Merrett, you’ll get it hot. Follow? There are five hundred and sixteen pages of this book. How much is that each, some one?”

A pause.

“Thirteen, exactly,” said Firmin.

“Thanks. Here’s your lot, Firmin,” said Linton. “Don’t mind them being a bit torn, do you?”

“Not a bit,” said Firmin. “Thanks.”

“You can have the cover, Merrett,” said Linton, when he had handed every one his portion of the prize. “Come in useful as an ornament for your mantelpiece at home.”

But Theodore never troubled to exhibit his share of the spoil in that way. And he still wants a banjo.

Madame Eulalie’s Rare Plums

Madame Eulalie’s Rare Plums