The Captain, January 1904

CHAPTER XIII.

Victim Number Three.

ITH

reference to our last communication,” ran the letter—the writer evidently

believed in the commercial style—“it may interest you to know that the bat you

lost by the statue on the night of the 26th of January has come into our

possession. We observe that Barry is still playing for the first fifteen.”

ITH

reference to our last communication,” ran the letter—the writer evidently

believed in the commercial style—“it may interest you to know that the bat you

lost by the statue on the night of the 26th of January has come into our

possession. We observe that Barry is still playing for the first fifteen.”

“And will jolly well continue to,” muttered Trevor, crumpling the paper viciously into a ball.

He went on writing the names for the Ripton match. The last name on the list was Barry’s.

Then he sat back in his chair, and began to wrestle with this new development. Barry must play. That was certain. All the bluff in the world was not going to keep him from playing the best man at his disposal in the Ripton match. He himself did not count. It was the school he had to think of. This being so, what was likely to happen? Though nothing was said on the point, he felt certain that if he persisted in ignoring the League, that bat would find its way somehow—by devious routes, possibly—to the headmaster or some one else in authority. And then there would be questions—awkward questions—and things would begin to come out. Then a fresh point struck him, which was, that whatever might happen would affect, not himself, but O’Hara. This made it rather more of a problem how to act. Personally, he was one of those dogged characters who can put up with almost anything themselves. If this had been his affair, he would have gone on his way without hesitating. Evidently the writer of the letter was under the impression that he had been the hero (or villain) of the statue escapade.

If everything came out it did not require any great effort of prophecy to predict what the result would be. O’Hara would go. Promptly. He would receive his marching orders within ten minutes of the discovery of what he had done. He would be expelled twice over, so to speak, once for breaking out at night—one of the most heinous offences in the school code—and once for tarring the statue. Anything that gave the school a bad name in the town was a crime in the eyes of the powers, and this was such a particularly flagrant case. Yes, there was no doubt of that. O’Hara would take the first train home without waiting to pack up. Trevor knew his people well, and he could imagine their feelings when the prodigal strolled into their midst—an old Wrykinian malgré lui. As the philosopher said of falling off a ladder, it is not the falling that matters: it is the sudden stopping at the other end. It is not the being expelled that is so peculiarly objectionable: it is the sudden homecoming. With this gloomy vision before him, Trevor almost wavered. But the thought that the selection of the team had nothing whatever to do with his personal feelings strengthened him. He was simply a machine, devised to select the fifteen best men in the school to meet Ripton. In his official capacity of football captain he was not supposed to have any feelings. However, he yielded in so far that he went to Clowes to ask his opinion.

Clowes, having heard everything and seen the letter, unhesitatingly voted for the right course. If fifty mad Irishmen were to be expelled, Barry must play against Ripton. He was the best man, and in he must go.

“That’s what I thought,” said Trevor. “It’s bad for O’Hara, though.”

Clowes remarked somewhat tritely that business was business.

“Besides,” he went on, “you’re assuming that the thing this letter hints at will really come off. I don’t think it will. A man would have to be such an awful blackguard to go as low as that. The least grain of decency in him would stop him. I can imagine a man threatening to do it as a piece of bluff—by the way, the letter doesn’t actually say anything of the sort, though I suppose it hints at it—but I can’t imagine anybody out of a melodrama doing it.”

“You can never tell,” said Trevor. He felt that this was but an outside chance. The forbearance of one’s antagonist is but a poor thing to trust to at the best of times.

“Are you going to tell O’Hara?” asked Clowes.

“I don’t see the good. Would you?”

“No. He can’t do anything, and it would only give him a bad time. There are pleasanter things, I should think, than going on from day to day not knowing whether you’re going to be sacked or not within the next twelve hours. Don’t tell him.”

“I won’t. And Barry plays against Ripton.”

“Certainly. He’s the best man.”

“I’m going over to Seymour’s now,” said Trevor, after a pause, “to see Milton. We’ve drawn Seymour’s in the next round of the house-matches. I suppose you knew. I want to get it over before the Ripton match, for several reasons. About half the fifteen are playing on one side or the other, and it’ll give them a good chance of getting fit. Running and passing is all right, but a good, hard game’s the thing for putting you into form. And then I was thinking that, as the side that loses, whichever it is——”

“Seymour’s, of course.”

“Hope so. Well, they’re bound to be a bit sick at losing, so they’ll play up all the harder on Saturday to console themselves for losing the cup.”

“My word, what strategy!” said Clowes. “You think of everything. When do you think of playing it, then?”

“Wednesday struck me as a good day. Don’t you think so?”

“It would do splendidly. It’ll be a good match. For all practical purposes, of course, it’s the final. If we beat Seymour’s, I don’t think the others will trouble us much.”

There was just time to see Milton before lock-up. Trevor ran across to Seymour’s, and went up to his study.

“Come in,” said Milton, in answer to his knock.

Trevor went in, and stood surprised at the difference in the look of the place since the last time he had visited it. The walls, once covered with photographs, were bare. Milton, seated before the fire, was ruefully contemplating what looked like a heap of waste cardboard.

Trevor recognised the symptoms. He had had experience.

“You don’t mean to say they’ve been at you, too!” he cried.

Milton’s normally cheerful face was thunderous and gloomy.

“Yes. I was thinking what I’d like to do to the man who ragged it.”

“It’s the League again, I suppose?”

Milton looked surprised.

“Again?” he said, “where did you hear of the League? This is the first time I’ve heard of its existence, whatever it is. What is the confounded thing, and why on earth have they played the fool here? What’s the meaning of this bally rot?”

He exhibited one of the variety of cards of which Trevor had already seen two specimens. Trevor explained briefly the style and nature of the League, and mentioned that his study also had been wrecked.

“Your study? Why, what have they got against you?”

“I don’t know,” said Trevor. Nothing was to be gained by speaking of the letters he had received.

“Did they cut up your photographs?”

“Every one.”

“I tell you what it is, Trevor, old chap,” said Milton, with great solemnity, “there’s a lunatic in the school. That’s what I make of it. A lunatic whose form of madness is wrecking studies.”

“But the same chap couldn’t have done yours and mine. It must have been a Donaldson’s fellow who did mine, and one of your chaps who did yours and Mill’s.”

“Mill’s? By Jove, of course. I never thought of that. That was the League, too, I suppose?”

“Yes. One of those cards was tied to a chair, but Clowes took it away before anybody saw it.”

Milton returned to the details of the disaster.

“Was there any ink spilt in your room?”

“Pints,” said Trevor, shortly. The subject was painful.

“So there was here,” said Milton, mournfully. “Gallons.”

There was silence for a while, each pondering over his wrongs.

“Gallons,” said Milton again. “I was ass enough to keep a large pot full of it here, and they used it all, every drop. You never saw such a sight.”

Trevor said he had seen one similar spectacle.

“And my photographs! You remember those photographs I showed you? All ruined. Slit across with a knife. Some torn in half. I wish I knew who did that.”

Trevor said he wished so, too.

“There was one of Mrs. Patrick Campbell,” Milton continued in heartrending tones, “which was torn into sixteen pieces. I counted them. There they are on the mantelpiece. And there was one of Little Tich” (here he almost broke down), “which was so covered with ink that for half an hour I couldn’t recognise it. Fact.”

Trevor nodded sympathetically.

“Yes,” said Milton. “Soaked.”

There was another silence. Trevor felt it would be almost an outrage to discuss so prosaic a topic as the date of a house-match with one so broken up. Yet time was flying, and lock-up was drawing near.

“Are you willing to play——” he began.

“I feel as if I could never play again,” interrupted Milton. “You’d hardly believe the amount of blotting-paper I’ve used to-day. It must have been a lunatic, Dick, old man.”

When Milton called Trevor “Dick,” it was a sign that he was moved. When he called him “Dick, old man,” it gave evidence of an internal upheaval without parallel.

“Why, who else but a lunatic would get up in the night to wreck another chap’s study? All this was done between eleven last night and seven this morning. I turned in at eleven, and when I came down here again at seven the place was a wreck. It must have been a lunatic.”

“How do you account for the printed card from the League?”

Milton murmured something about madmen’s cunning and diverting suspicion, and relapsed into silence. Trevor seized the opportunity to make the proposal he had come to make, that Donaldson’s v. Seymour’s should be played on the following Wednesday.

Milton agreed listlessly.

“Just where you’re standing,” he said, “I found a photograph of Sir Henry Irving so slashed about that I thought at first it was Huntley Wright in San Toy.”

“Start at two-thirty sharp,” said Trevor.

“I had seventeen of Edna May,” continued the stricken Seymourite, monotonously. “In various attitudes. All destroyed.”

“On the first fifteen ground, of course,” said Trevor. “I’ll get Aldridge to referee. That’ll suit you, I suppose?”

“All right. Anything you like. Just by the fireplace I found the remains of Arthur Roberts in H.M.S. Irresponsible. And part of Seymour Hicks. Under the table——”

Trevor departed.

CHAPTER XIV.

The White Figure.

UPPOSE,”

said Shoeblossom to Barry, as they were walking over to school on the morning

following the day on which Milton’s study had passed through the hands of the

League, “suppose you thought somebody had done something, but you weren’t quite

certain who, but you knew it was some one, what would you do?”

UPPOSE,”

said Shoeblossom to Barry, as they were walking over to school on the morning

following the day on which Milton’s study had passed through the hands of the

League, “suppose you thought somebody had done something, but you weren’t quite

certain who, but you knew it was some one, what would you do?”

“What on earth do you mean?” inquired Barry.

“I was trying to make an A.B. case of it,” explained Shoeblossom.

“What’s an A.B. case?”

“I don’t know,” admitted Shoeblossom, frankly. “But it comes in a book of Stevenson’s. I think it must mean a sort of case where you call everyone A. and B. and don’t tell their names.”

“Well, go ahead.”

“It’s about Milton’s study.”

“What! what about it?”

“Well, you see, the night it was ragged I was sitting in my study with a dark lantern——”

“Well?”

Shoeblossom proceeded to relate the moving narrative of his night-walking adventure. He dwelt movingly on his state of mind when standing behind the door, waiting for Mr Seymour to come in and find him. He related with appropriate force the hair-raising episode of the weird white figure. And then he came to the conclusions he had since drawn (in calmer moments) from that apparition’s movements.

“You see,” he said, “I saw it coming out of Milton’s study, and that must have been about the time the study was ragged. And it went into Rigby’s dorm. So it must have been a chap in that dorm. who did it.”

Shoeblossom was quite clever at rare intervals. Even Barry, whose belief in his sanity was of the smallest, was compelled to admit that here, at any rate, he was talking sense.

“What would you do?” asked Shoeblossom.

“Tell Milton, of course,” said Barry.

“But he’d give me beans for being out of the dorm. after lights-out.”

This was a distinct point to be considered. The attitude of Barry towards Milton was different from that of Shoeblossom. Barry regarded him—through having played with him in important matches—as a good sort of fellow who had always behaved decently to him. Leather-Twigg, on the other hand, looked on him with undisguised apprehension, as one in authority who would give him lines the first time he came into contact with him, and cane him if he ever did it again. He had a decided disinclination to see Milton on any pretext whatever.

“Suppose I tell him?” suggested Barry.

“You’ll keep my name dark?” said Shoeblossom, alarmed.

Barry said he would make an A.B. case of it.

After school he went to Milton’s study, and found him still brooding over its departed glories.

“I say, Milton, can I speak to you for a second?”

“Hullo, Barry. Come in.”

Barry came in.

“I had forty-three photographs,” began Milton, without preamble. “All destroyed. And I’ve no money to buy any more. I had seventeen of Edna May.”

Barry, feeling that he was expected to say something, said, “By Jove! Really?”

“In various positions,” continued Milton. “All ruined.”

“Not really?” said Barry.

“There was one of Little Tich——”

But Barry felt unequal to playing the part of chorus any longer. It was all very thrilling, but, if Milton was going to run through the entire list of his destroyed photographs, life would be too short for conversation on any other topic.

“I say, Milton,” he said, “it was about that that I came. I’m sorry——”

Milton sat up.

“It wasn’t you who did this, was it?”

“No, no,” said Barry, hastily.

“Oh, I thought from your saying you were sorry——”

“I was going to say I thought I could put you on the track of the chap who did do it——”

For the second time since the interview began Milton sat up.

“Go on,” he said.

“——But I’m sorry I can’t give you the name of the fellow who told me about it.”

“That doesn’t matter,” said Milton. “Tell me the name of the fellow who did it. That’ll satisfy me.”

“I’m afraid I can’t do that, either.”

“Have you any idea what you can do?” asked Milton, satirically.

“I can tell you something which may put you on the right track.”

“That’ll do for a start. Well?”

“Well, the chap who told me—I’ll call him A.; I’m going to make an A.B. case of it—was coming out of his study at about one o’clock in the morning——”

“What the deuce was he doing that for?”

“Because he wanted to go back to bed,” said Barry.

“About time, too. Well?”

“As he was going past your study, a white figure emerged——”

“I should strongly advise you, young Barry,” said Milton, gravely, “not to try and rot me in any way. You’re a jolly good wing three-quarters, but you shouldn’t presume on it. I’d slay the Old Man himself if he rotted me about this business.”

Barry was quite pained at this sceptical attitude in one whom he was going out of his way to assist.

“I’m not rotting,” he protested. “This is all quite true.”

“Well, go on. You were saying something about white figures emerging.”

“Not white figures. A white figure,” corrected Barry. “It came out of your study——”

“——And vanished through the wall?”

“It went into Rigby’s dorm.,” said Barry, sulkily. It was maddening to have an exclusive bit of news treated in this way.

“Did it, by Jove!” said Milton, interested at last. “Are you sure the chap who told you wasn’t pulling your leg? Who was it told you?”

“I promised him not to say.”

“Out with it, young Barry.”

“I won’t,” said Barry.

“You aren’t going to tell me?”

“No.”

Milton gave up the point with much cheerfulness. He liked Barry, and he realised that he had no right to try and make him break his promise.

“That’s all right,” he said. “Thanks very much, Barry. This may be useful.”

“I’d tell you his name if I hadn’t promised, you know, Milton.”

“It doesn’t matter,” said Milton. “It’s not important.”

“Oh, there was one thing I forgot. It was a biggish chap the fellow saw.”

“How big! My size?”

“Not quite so tall, I should think. He said he was about Seymour’s size.”

“Thanks. That’s worth knowing. Thanks very much, Barry.”

When his visitor had gone, Milton proceeded to unearth one of the printed lists of the house which were used for purposes of roll-call. He meant to find out who were in Rigby’s dormitory. He put a tick against the names. There were eighteen of them. The next thing was to find out which of them was about the same height as Mr. Seymour. It was a somewhat vague description, for the house-master stood about five feet nine or eight, and a good many of the dormitory were that height, or near it. At last, after much brain-work, he reduced the number of “possibles” to seven. These seven were Rigby himself, Linton, Rand-Brown, Griffith, Hunt, Kershaw, and Chapple. Rigby might be scratched off the list at once. He was one of Milton’s greatest friends. Exeunt also Griffith, Hunt, and Kershaw. They were mild youths, quite incapable of any deed of devilry. There remained, therefore, Chapple, Linton, and Rand-Brown. Chapple was a boy who was invariably late for breakfast. The inference was that he was not likely to forego his sleep for the purpose of wrecking studies. Chapple might disappear from the list. Now there were only Linton and Rand-Brown to be considered. His suspicions fell on Rand-Brown. Linton was the last person, he thought, to do such a low thing. He was a cheerful, rollicking individual, who was popular with everyone and seemed to like everyone. He was not an orderly member of the house, certainly, and on several occasions Milton had found it necessary to drop on him heavily for creating disturbances. But he was not the sort that bears malice. He took it all in the way of business, and came up smiling after it was over. No, everything pointed to Rand-Brown. He and Milton had never got on well together, and quite recently they had quarrelled openly over the former’s play in the Day’s match. Rand-Brown must be the man. But Milton was sensible enough to feel that so far he had no real evidence whatever. He must wait.

On the following afternoon Seymour’s turned out to play Donaldson’s.

The game, like most house-matches, was played with the utmost keenness. Both teams had good three-quarters, and they attacked in turn. Seymour’s had the best of it forward, where Milton was playing a great game, but Trevor in the centre was the best outside on the field, and pulled up rush after rush. By half-time neither side had scored.

After half-time Seymour’s, playing down-hill, came away with a rush to the Donaldsonites’ half, and Rand-Brown, with one of the few decent runs he had made in good class football that term, ran in on the left. Milton took the kick, but failed, and Seymour’s led by three points. For the next twenty minutes nothing more was scored. Then, when five minutes more of play remained, Trevor gave Clowes an easy opening, and Clowes sprinted between the posts. The kick was an easy one, and what sporting reporters term “the major points” were easily added.

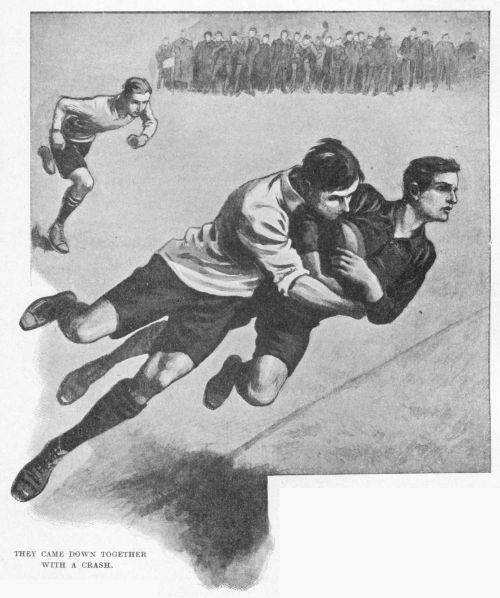

When there are five more minutes to play in an important house-match, and one side has scored a goal and the other a try, play is apt to become spirited. Both teams were doing all they knew. The ball came out to Barry on the right. Barry’s abilities as a three-quarter rested chiefly on the fact that he could dodge well. This eel-like attribute compensated for a certain lack of pace. He was past the Donaldson’s three-quarters in an instant, and running for the line, with only the back to pass, and with Clowes in hot pursuit. Another wriggle took him past the back, but it also gave Clowes time to catch him up. Clowes was a far faster runner, and he got to him just as he reached the twenty-five line. They came down together with a crash, Clowes on top, and as they fell the whistle blew.

“No side,” said Mr. Aldridge, the master who was refereeing.

Clowes got up.

“All over,” he said. “Jolly good game. Hullo, what’s up?”

For Barry seemed to be in trouble.

“You might give us a hand up,” said the latter. “I believe I’ve twisted my beastly ankle or something.”

CHAPTER XV.

A Sprain and a Vacant Place.

SAY,” said Clowes, helping him up, “I’m awfully sorry. Did I do it?

How did it happen?”

SAY,” said Clowes, helping him up, “I’m awfully sorry. Did I do it?

How did it happen?”

Barry was engaged in making various attempts at standing on the injured leg. The process seemed to be painful.

“Shall I get a stretcher or anything? Can you walk?”

“If you’d help me over to the house, I could manage all right. What a beastly nuisance! It wasn’t your fault a bit. Only you tackled me when I was just trying to swerve, and my ankle was all twisted.”

Drummond came up, carrying Barry’s blazer and sweater.

“Hullo, Barry,” he said, “what’s up? You aren’t crocked?”

“Something gone wrong with my ankle. That my blazer? Thanks. Coming over to the house? Clowes was just going to help me over.”

Clowes asked a Donaldson’s junior, who was lurking near at hand, to fetch his blazer and carry it over to the house, and then made his way with Drummond and the disabled Barry to Seymour’s. Having arrived at the senior day-room, they deposited the injured three-quarter in a chair, and sent McTodd, who came in at the moment, to fetch the doctor.

Dr. Oakes was a big man with a breezy manner, the sort of doctor who hits you with the force of a sledgehammer in the small ribs, and asks you if you felt anything then. It was on this principle that he acted with regard to Barry’s ankle. He seized it in both hands and gave it a wrench.

“Did that hurt?” he inquired anxiously.

Barry turned white, and replied that it did.

Dr. Oakes nodded wisely.

“Ah! H’m! Just so. ’Myes. Ah.”

“Is it bad?” asked Drummond, awed by these mystic utterances.

“My dear boy,” replied the doctor, breezily, “it is always bad when one twists one’s ankle.”

“How long will it do me out of footer?” asked Barry.

“How long? How long? How long? Why, fortnight. Fortnight,” said the doctor.

“Then I sha’n’t be able to play next Saturday?”

“Next Saturday? Next Saturday? My dear boy, if you can put your foot to the ground by next Saturday, you may take it as evidence that the age of miracles is not past. Next Saturday, indeed! Ha, ha.”

It was not altogether his fault that he treated the matter with such brutal levity. It was a long time since he had been at school, and he could not quite realise what it meant to Barry not to be able to play against Ripton. As for Barry, he felt that he had never loathed and detested any one so thoroughly as he loathed and detested Dr. Oakes at that moment.

“I don’t see where the joke comes in,” said Clowes, when he had gone. “I bar that man.”

“He’s a beast,” said Drummond. “I can’t understand why they let a tout like that be the school doctor.”

Barry said nothing. He was too sore for words.

What Dr. Oakes said to his wife that evening was: “Over at the school, my dear, this afternoon. This afternoon. Boy with a twisted ankle. Nice young fellow. Very much put out when I told him he could not play football for a fortnight. But I chaffed him, and cheered him up in no time. I cheered him up in no time, my dear.”

“I’m sure you did, dear,” said Mrs. Oakes. Which shows how differently the same thing may strike different people. Barry certainly did not look as if he had been cheered up when Clowes left the study and went over to tell Trevor that he would have to find a substitute for his right wing three-quarter against Ripton.

Trevor had left the field without noticing Barry’s accident, and he was tremendously pleased at the result of the game.

“Good man,” he said, when Clowes came in, “you saved the match.”

“And lost the Ripton match probably,” said Clowes, gloomily.

“What do you mean?”

“That last time I brought down Barry I crocked him. He’s in his study now with a sprained ankle. I’ve just come from there. Oakes has seen him and says he mustn’t play for a fortnight.”

“Great Scott!” said Trevor, blankly. “What on earth shall we do?”

“Why not move Strachan up to the wing, and put somebody else back instead of him? Strachan is a good wing.”

Trevor shook his head.

“No. There’s nobody good enough to play back for the first. We mustn’t risk it.”

“Then I suppose it must be Rand-Brown?”

“I suppose so.”

“He may do better than we think. He played quite a decent game to-day. That try he got wasn’t half a bad one.”

“He’d be all right if he didn’t funk. But perhaps he wouldn’t funk against Ripton. In a match like that anybody would play up. I’ll ask Milton and Allardyce about it.”

“I shouldn’t go to Milton to-day,” said Clowes. “I fancy he’ll want a night’s rest before he’s fit to talk to. He must be a bit sick about this match. I know he expected Seymour’s to win.”

He went out, but came back almost immediately.

“I say,” he said, “there’s one thing that’s just occurred to me. This’ll please the League. I mean, this ankle business of Barry’s.”

The same idea had struck Trevor. It was certainly a respite. But he regretted it for all that. What he wanted was to beat Ripton, and Barry’s absence would weaken the team. However, it was good in its way, and cleared the atmosphere for the time. The League would hardly do anything with regard to the carrying out of their threat while Barry was on the sick-list.

Next day, having given him time to get over the bitterness of defeat in accordance with Clowes’ thoughtful suggestion, Trevor called on Milton, and asked him what his opinion was on the subject of the inclusion of Rand-Brown in the first fifteen in place of Barry.

“He’s the next best man,” he added, in defence of the proposal.

“I suppose so,” said Milton. “He’d better play, I suppose. There’s no one else.”

“Clowes thought it wouldn’t be a bad idea to shove Strachan on the wing, and put somebody else back.”

“Who is there to put?”

“Jervis?”

“Not good enough. No, it’s better to be weakish on the wing than at back. Besides, Rand-Brown may do all right. He played well against you.”

“Yes,” said Trevor. “Study looks a bit better now,” he added, as he was going, having looked round the room. “Still a bit bare, though.”

Milton sighed.

“It will never be what it was.”

“Forty-three theatrical photographs want some replacing, of course,” said Trevor. “But it isn’t bad, considering.”

“How’s yours?”

“Oh, mine’s all right, except for the absence of photographs.”

“I say, Trevor.”

“Yes?” said Trevor, stopping at the door. Milton’s voice had taken on the tone of one who is about to disclose dreadful secrets.

“Would you like to know what I think?”

“What?”

“Why, I’m pretty nearly sure who it was that ragged my study?”

“By Jove! What have you done to him?”

“Nothing as yet. I’m not quite sure of my man.”

“Who is the man?”

“Rand-Brown.”

“By Jove! Clowes once said he thought Rand-Brown must be the president of the League. But then, I don’t see how you can account for my study being wrecked. He was out on the field when it was done.”

“Why, the League, of course. You don’t suppose he’s the only man in it? There must be a lot of them.”

“But what makes you think it was Rand-Brown?”

Milton told him the story of Shoeblossom, as Barry had told it to him. The only difference was that Trevor listened without any of the scepticism which Milton had displayed on hearing it. He was getting excited. It all fitted in so neatly. If ever there was circumstantial evidence against a man, here it was against Rand-Brown. Take the two cases. Milton had quarrelled with him. Milton’s study was wrecked “with the compliments of the League.” Trevor had turned him out of the first fifteen. Trevor’s study was wrecked “with the compliments of the League.” As Clowes had pointed out, the man with the most obvious motive for not wishing Barry to play for the school was Rand-Brown. It seemed a true bill.

“I shouldn’t wonder if you’re right,” he said, “but of course one can’t do anything yet. You want a lot more evidence. Anyhow, we must play him against Ripton, I suppose. Which is his study? I’ll go and tell him now.”

“Ten.”

Trevor knocked at the door of study Ten. Rand-Brown was sitting over the fire, reading. He jumped up when he saw that it was Trevor who had come in, and to his visitor it seemed that his face wore a guilty look.

“What do you want?” said Rand-Brown.

It was not the politest way of welcoming a visitor. It increased Trevor’s suspicions. The man was afraid. A great idea darted into his mind. Why not go straight to the point and have it out with him here and now? He had the League’s letter about the bat in his pocket. He would confront him with it and insist on searching the study there and then. If Rand-Brown were really, as he suspected, the writer of the letter, the bat must be in this room somewhere. Search it now, and he would have no time to hide it. He pulled out the letter.

“I believe you wrote that,” he said.

Trevor was always direct.

Rand-Brown seemed to turn a little pale, but his voice when he replied was quite steady.

“That’s a lie,” he said.

“Then, perhaps,” said Trevor, “you wouldn’t object to proving it.”

“How?”

“By letting me search your study?”

“You don’t believe my word?”

“Why should I? You don’t believe mine.”

Rand-Brown made no comment on this remark.

“Was that what you came here for?” he asked.

“No,” said Trevor; “as a matter of fact, I came to tell you to turn out for running and passing with the first to-morrow afternoon. You’re playing against Ripton on Saturday.”

Rand-Brown’s attitude underwent a complete transformation at the news. He became friendliness itself.

“All right,” he said. “I say, I’m sorry I said what I did about lying. I was rather sick that you should think I wrote that rot you showed me. I hope you don’t mind.”

“Not a bit. Do you mind my searching your study?”

For a moment Rand-Brown looked vicious. Then he sat down with a laugh.

“Go on,” he said; “I see you don’t believe me. Here are the keys, if you want them.”

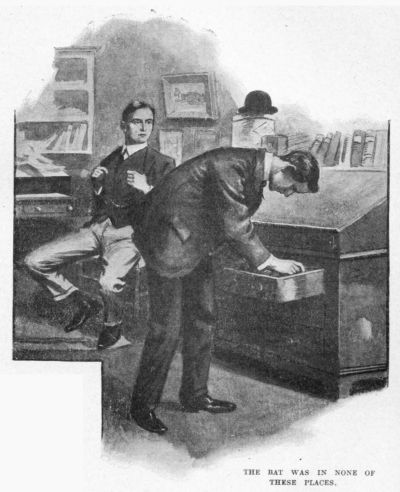

Trevor thanked him, and took the keys. He opened every drawer and examined the writing-desk. The bat was in none of these places. He looked in the cupboards. No bat there.

“Like to take up the carpet?” inquired Rand-Brown.

“No, thanks.”

“Search me if you like. Shall I turn out my pockets?”

“Yes, please,” said Trevor, to his surprise. He had not expected to be taken literally.

Rand-Brown emptied them, but the bat was not there. Trevor turned to go.

“You’ve not looked inside the legs of the chairs yet,” said Rand-Brown. “They may be hollow. There’s no knowing.”

“It doesn’t matter, thanks,” said Trevor. “Sorry for troubling you. Don’t forget to-morrow afternoon.”

And he went, with the very unpleasant feeling that he had been badly scored off.

CHAPTER XVI.

The Ripton Match.

T

was a curious thing in connection with the matches between Ripton and Wrykyn

that Ripton always seemed to be the bigger team. They always had a

gigantic pack of forwards, who looked capable of shoving a hole through one of

the pyramids. Possibly they looked bigger to the Wrykinians than they

really were. Strangers always look big on the football field. When

you have grown accustomed to a person’s appearance, he does not look nearly so

large. Milton, for instance, never struck anybody at Wrykyn as being

particularly big for a school forward, and yet to-day he was the heaviest man on

the field by a quarter of a stone. But, taken in the mass, the Ripton

pack were far heavier than their rivals. There was a legend current among

the lower forms at Wrykyn that fellows were allowed to stop on at Ripton till

they were twenty-five, simply to play football. This is scarcely likely

to have been based on fact. Few lower form legends are.

T

was a curious thing in connection with the matches between Ripton and Wrykyn

that Ripton always seemed to be the bigger team. They always had a

gigantic pack of forwards, who looked capable of shoving a hole through one of

the pyramids. Possibly they looked bigger to the Wrykinians than they

really were. Strangers always look big on the football field. When

you have grown accustomed to a person’s appearance, he does not look nearly so

large. Milton, for instance, never struck anybody at Wrykyn as being

particularly big for a school forward, and yet to-day he was the heaviest man on

the field by a quarter of a stone. But, taken in the mass, the Ripton

pack were far heavier than their rivals. There was a legend current among

the lower forms at Wrykyn that fellows were allowed to stop on at Ripton till

they were twenty-five, simply to play football. This is scarcely likely

to have been based on fact. Few lower form legends are.

Jevons, the Ripton captain, through having played opposite Trevor for three seasons—he was the Ripton left centre-three-quarter—had come to be quite an intimate of his. Trevor had gone down with Milton and Allardyce to meet the team at the station, and conduct them up to the school.

“How have you been getting on since Christmas?” asked Jevons.

“Pretty well. We’ve lost Paget, I suppose you know?”

“That was the fast man on the wing, wasn’t it?”

“Yes.”

“Well, we’ve lost a man, too.”

“Oh, yes, that red-haired forward. I remember him.”

“It ought to make us pretty even. What’s the ground like?”

“Bit greasy, I should think. We had some rain late last night.”

The ground was a bit greasy. So was the ball. When Milton kicked off up the hill with what wind there was in his favour, the outsides of both teams found it difficult to hold the ball. Jevons caught it on his twenty-five line, and promptly handed it forward. The first scrum was formed in the heart of the enemy’s country.

A deep, swelling roar from either touchline greeted the school’s advantage. A feature of a big match was always the shouting. It rarely ceased throughout the whole course of the game, the monotonous but impressive sound of five hundred voices all shouting the same word. It was worth hearing. Sometimes the evenness of the noise would change to an excited crescendo as a school three-quarter got off, or the school back pulled up the attack with a fine piece of defence. Sometimes the shouting would give place to clapping when the school was being pressed and somebody had found touch with a long kick. But mostly the man on the ropes roared steadily and without cessation, and with the full force of his lungs, the word “Wrykyn!”

The scrum was a long one. For two minutes the forwards heaved and strained, now one side, now the other, gaining a few inches. The Wrykyn pack were doing all they knew to heel, but their opponents’ superior weight was telling. Ripton had got the ball, and were keeping it. Their game was to break through with it and rush. Then suddenly one of their forwards kicked it on, and just at that moment the opposition of the Wrykyn pack gave way, and the scrum broke up. The ball came out on the Wrykyn side, and Allardyce whipped it out to Deacon, who was playing half with him.

“Ball’s out,” cried the Ripton half who was taking the scrum. “Break up. It’s out.”

And his colleague on the left darted across to stop Trevor, who had taken Deacon’s pass, and was running through on the right.

Trevor ran splendidly. He was a three-quarter who took a lot of stopping when he once got away. Jevons and the Ripton half met him almost simultaneously, and each slackened his pace for the fraction of a second, to allow the other to tackle. As they hesitated, Trevor passed them. He had long ago learned that to go hard when you have once started is the thing that pays.

He could see that Rand-Brown was racing up for the pass, and, as he reached the back, he sent the ball to him, waist-high. Then the back got to him, and he came down with a thud, with a vision, seen from the corner of his eye, of the ball bounding forward out of the wing three-quarter’s hands into touch. Rand-Brown had bungled the pass in the old familiar way, and lost a certain try.

The touch-judge ran up with his flag waving in the air, but the referee had other views.

“Knocked on inside,” he said; “scrum here.”

“Here” was, Trevor saw with unspeakable disgust, some three yards from the goal-line. Rand-Brown had only had to take the pass, and he must have scored.

The Ripton forwards were beginning to find their feet better now, and they carried the scrum. A truculent-looking warrior in one of those ear-guards which are tied on by strings underneath the chin, and which add fifty per cent. to the ferocity of a forward’s appearance, broke away with the ball at his feet, and swept down the field with the rest of the pack at his heels. Trevor arrived too late to pull up the rush, which had gone straight down the right touchline, and it was not till Strachan fell on the ball on the Wrykyn twenty-five line that the danger ceased to threaten.

Even now the school were in a bad way. The enemy were pressing keenly, and a real piece of combination among their three-quarters would only too probably end in a try. Fortunately for them, Allardyce and Deacon were a better pair of halves than the couple they were marking. Also, the Ripton forwards heeled slowly, and Allardyce had generally got his man safely buried in the mud before he could pass.

He was just getting round for the tenth time to bottle his opponent as before, when he slipped. When the ball came out he was on all fours, and the Ripton exponent, finding to his great satisfaction that he had not been tackled, whipped the ball out on the left, where a wing three-quarter hovered.

This was the man Rand-Brown was supposed to be marking, and once again did Barry’s substitute prove of what stuff his tackling powers were made. After his customary moment of hesitation, he had at the Riptonian’s neck. The Riptonian handed him off in a manner that recalled the palmy days of the old Prize Ring—handing off was always slightly vigorous in the Ripton v. Wrykyn match—and dashed over the line in the extreme corner.

There was anguish on the two touchlines. Trevor looked savage, but made no comment. The team lined up in silence.

It takes a phenomenal kick to convert a try from the touchline. Jevons’ kick was a long one, but it fell short. Ripton led by a try to nothing.

A few more scrums near the halfway line, and a fine attempt at a dropped goal by the Ripton back, and it was half-time, with the score unaltered.

During the interval there were lemons. An excellent thing is your lemon at half-time. It cools the mouth, quenches the thirst, stimulates the desire to be at them again, and improves the play.

Possibly the Wrykyn team had been happier in their choice of lemons on this occasion, for no sooner had the game been restarted than Clowes ran the whole length of the field, dodged through the three-quarters, punted over the back’s head, and scored a really brilliant try, of the sort that Paget had been fond of scoring in the previous term. The man on the touchline brightened up wonderfully, and began to try and calculate the probable score by the end of the game, on the assumption that, as a try had been scored in the first two minutes, ten would be scored in the first twenty, and so on.

But the calculations were based on false premises. After Strachan had failed to convert, and the game had been resumed with the score at one try all, play settled down in the centre and neither side could pierce the other’s defence. Once Jevons got off for Ripton, but Trevor brought him down safely, and once Rand-Brown let his man through, as before, but Strachan was there to meet him, and the effort came to nothing. For Wrykyn, no one did much except tackle. The forwards were beaten by the heavier pack, and seldom let the ball out. Allardyce intercepted a pass when about ten minutes of play remained, and ran through to the back. But the back, who was a capable man and in his third season in the team, laid him low scientifically before he could reach the line.

Altogether it looked as if the match were going to end in a draw. The Wrykyn defence, with the exception of Rand-Brown, was too good to be penetrated, while the Ripton forwards, by always getting the ball in the scrums, kept them from attacking. It was about five minutes from the end of the game when the Ripton right centre-three-quarter, in trying to punt across to the wing, miskicked and sent the ball straight into the hands of Trevor’s colleague in the centre. Before his man could get round to him he had slipped through, with Trevor backing him up. The back, as a good back should, seeing two men coming at him, went for the man with the ball. But by the time he had brought him down, the ball was no longer where it had originally been. Trevor had got it, and was running in between the posts.

This time Strachan put on the extra two points without difficulty.

Ripton played their hardest for the remaining minutes, but without result. The game ended with Wrykyn a goal ahead—a goal and a try to a try. For the second time in one season the Ripton match had ended in a victory—a thing it was very rarely in the habit of doing.

The senior day-room at Seymour’s rejoiced considerably that night. The air was dark with flying cushions, and darker still, occasionally, when the usual humorist turned the gas out. Milton was out, for he had gone to the dinner which followed the Ripton match, and the man in command of the house in his absence was Mill. And the senior day-room had no respect whatever for Mill.

Barry joined in the revels as well as his ankle would let him, but he was not feeling happy. The disappointment of being out of the first still weighed on him.

At about eight, when things were beginning to grow really lively, and the noise seemed likely to crack the window at any moment, the door was flung open and Milton stalked in.

“What’s all this row?” he inquired. “Stop it at once.”

As a matter of fact the row had stopped—directly he came in.

“Is Barry here?” he asked.

“Yes,” said that youth.

“Congratulate you on your first, Barry. We’ve just had a meeting and given you your colours. Trevor told me to tell you.”

(To be continued.)

Madame Eulalie’s Rare Plums

Madame Eulalie’s Rare Plums