The Captain, August 1902

ATTITUDE of Philip St. H. Harrison, of Merevale’s house, towards his

fellow man was outwardly one of genial and even sympathetic toleration.

Did his form-master intimate that his conduct was not his idea

of what Young England’s conduct should be, P. St. H. Harrison agreed

cheerfully with every word he said, warmly approved his intention of

laying the matter before the headmaster, and accepted his punishment

with the air of a waiter booking an order for a chump chop and fried

potatoes. But the next day there would be a squeaking desk in the

form-room just to show the master that he had not been forgotten. Or,

again, did the captain of his side at football speak rudely to him on

the subject of kicking the ball through in the scrum, Harrison would

smile gently, and at the earliest opportunity tread heavily on the

captain’s toe. In short, he was a youth who made a practice of taking

very good care of himself. Yet he had his failures. The affair of

Graham’s mackintosh was one of them, and it affords an excellent

example of the truth of the proverb that a cobbler should stick to his

last. Harrison’s forte was diplomacy. When he forsook the arts

of the diplomatist for those of the brigand, he naturally went wrong.

And the manner of these things was thus.

ATTITUDE of Philip St. H. Harrison, of Merevale’s house, towards his

fellow man was outwardly one of genial and even sympathetic toleration.

Did his form-master intimate that his conduct was not his idea

of what Young England’s conduct should be, P. St. H. Harrison agreed

cheerfully with every word he said, warmly approved his intention of

laying the matter before the headmaster, and accepted his punishment

with the air of a waiter booking an order for a chump chop and fried

potatoes. But the next day there would be a squeaking desk in the

form-room just to show the master that he had not been forgotten. Or,

again, did the captain of his side at football speak rudely to him on

the subject of kicking the ball through in the scrum, Harrison would

smile gently, and at the earliest opportunity tread heavily on the

captain’s toe. In short, he was a youth who made a practice of taking

very good care of himself. Yet he had his failures. The affair of

Graham’s mackintosh was one of them, and it affords an excellent

example of the truth of the proverb that a cobbler should stick to his

last. Harrison’s forte was diplomacy. When he forsook the arts

of the diplomatist for those of the brigand, he naturally went wrong.

And the manner of these things was thus.

Tony Graham was a prefect in Merevale’s, and part of his duties was to look after the dormitory of which Harrison was one of the ornaments. It was a dormitory that required a good deal of keeping in order. Such choice spirits as Braithwaite of the Upper Fourth, and Mace, who was rapidly driving the master of the Lower Fifth into a premature grave, needed a firm hand. Indeed, they generally needed not only a firm hand, but a firm hand grasping a serviceable walking-stick. Add to these Harrison himself, and others of a similar calibre, and it will be seen that Graham’s post was no sinecure. It was Harrison’s custom to throw off his mask at night with his other garments, and appear in his true character of an abandoned villain, willing to stick at nothing as long as he could do it strictly incog. In this capacity he had come into constant contact with Graham. Even in the dark it is occasionally possible for a prefect to tell where a noise comes from. And if the said prefect has been harassed six days in the week by a noise, and locates it suddenly on the seventh, it is wont to be bad for the producer and patentee of same.

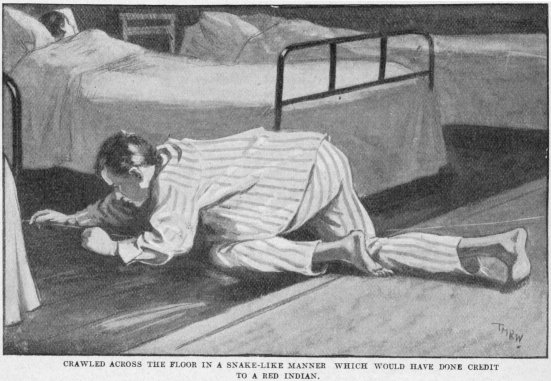

And so it came about that Harrison, enjoying himself one night after the manner of his kind, was suddenly dropped upon with violence. He had constructed an ingenious machine consisting of a biscuit tin, some pebbles, and some string. He put the pebbles in the tin, tied the string to it, and placed it under a chest of drawers. Then he took the other end of the string to bed with him, and settled down to make a night of it. At first all went well. Repeated enquiries from Tony failed to produce the author of the disturbance, and when finally the questions ceased and the prefect appeared to have given the matter up as a bad job, P. St. H. Harrison began to feel that under certain circumstances life was worth living. It was while he was in this happy frame of mind that the string, with which he had just produced a triumphant rattle from beneath the chest of drawers, was seized, and the next instant its owner was enjoying the warmest minute of a chequered career. Tony, like Brer Rabbit, had laid low until he was certain of the direction from which the sound proceeded. He had then slipped out of bed, crawled across the floor in a snake-like manner which would have done credit to a red Indian, found the tin and traced the string to its owner. Harrison emerged from the encounter feeling sore and unfit for any further recreation. This deed of the night left its impression on Harrison. The account had to be squared somehow, and in a few days his chance came. Merevale’s were playing a “friendly” with the School House, and in default of anybody better Harrison had been pressed into service as umpire. This in itself had annoyed him. Cricket was not in his line—he was not one of your flannelled fools—and of all things in connection with the game he loathed umpiring most.

When, however, Tony came on to bowl at his end, vice Charteris, who had been hit for three fours in an over by Scott, the school slogger, he recognized that even umpiring had its advantages, and resolved to make the most of the situation.

Scott had the bowling, and he lashed out at Tony’s first ball in his usual reckless style. There was an audible click, and what the sporting papers call confident appeals came simultaneously from Welch, Merevale’s captain, who was keeping wicket, and Tony himself. Even Scott seemed to know that his time had come. He moved a step or two away from the wicket, but stopped before going further to look at the umpire on the off-chance of a miracle happening to turn his decision in the batsman’s favour.

The miracle happened.

“Not out,” said Harrison.

“Awfully curious,” he added genially to Tony, “how like a bat those bits of grass sound! You have to be jolly smart to know where a noise comes from, don’t you!”

Tony grunted disgustedly, and walked back again to the beginning of his run.

If ever, in the whole history of cricket, a man was out leg-before wicket, Scott was so out to Tony’s second ball. It was hardly worth appealing for such a certainty. Still, the formality had to be gone through.

“How was that?” enquired Tony.

“Not out. It’s an awful pity, don’t you think, that they don’t bring in that new leg-before rule?”

“Seems to me,” said Tony bitterly, “the old rule holds pretty good when a man’s leg’s bang in front.”

“Rather. But you see the ball didn’t pitch straight, and the rule says——”

“Oh, all right,” said Tony.

The next ball Scott hit for four, and the next after that for a couple. The fifth was a yorker, and just grazed the leg stump. The sixth was a beauty. You could see it was going to beat the batsman from the moment it left Tony’s hand. Harrison saw it perfectly.

“No ball,” he shouted. And just as he spoke Scott’s off stump ricochetted towards the wicket-keeper.

“Heavens, man,” said Tony fairly roused out of his cricket manners, a very unusual thing for him, “I’ll swear my foot never went over the crease. Look, there’s the mark.”

“Rather not. Only, you see, it seemed to me you chucked that time. Of course, I know you didn’t mean to, and all that sort of thing, but still, the rules——”

Tony would probably have liked to have said something very forcible about the rules at this point, but it occurred to him that after all Harrison was only within his rights, and that it was bad form to dispute the umpire’s decision. Harrison walked off towards square-leg with a holy joy.

But he was too much of an artist to overdo the thing. Tony’s next over passed off without interference. Possibly, however, this was because it was a very bad one. After the third over he asked Welch if he could get somebody else to umpire, as he had work to do. Welch heaved a sigh of relief, and agreed readily.

“Conscientious sort of chap that umpire of yours,” said Scott to Tony, after the match. Scott had made a hundred and four, and was feeling pleased. “Considering he’s in your house, he was awfully fair.”

“You mean that we generally swindle, I suppose?”

“Of course not, you rotter. You know what I mean. But, I say, that catch Welch and you appealed for must have been a near thing. I could have sworn I hit it.”

“Of course you did. It was clean out. So was the lbw. I say, did you think that ball that bowled you was a chuck? That one in my first over, you know.”

“Chuck! My dear Tony, you don’t mean to say that man pulled you up for chucking? I thought your foot must have gone over the crease.”

“I believe the chap’s mad,” said Tony.

“Perhaps he’s taking it out of you this way for treading on his corns somehow. Have you been milling with this gentle youth lately?”

“By jove,” said Tony, “you’re right. I gave him beans only the other night for ragging in the dormitory.”

Scott laughed.

“Well, he seems to have been getting a bit of his own back to-day. Lucky the game was only a friendly. Why will you let your angry passions rise, Tony? You’ve wrecked your analysis by it, though it’s improved my average considerably. I don’t know if that’s any solid satisfaction to you?”

“It isn’t.”

“You don’t say so! Well, so long. If I were you, I should keep an eye on that conscientious umpire.”

“I will,” said Tony. “Good night.”

The process of keeping an eye on Harrison brought no results. When he wished to behave himself well, he could. On such occasions Sandford and Merton were literally not in it with him, and the hero of a Sunday school story would simply have refused to compete. But Nemesis, as the poets tell us, though no sprinter, manages, like the celebrated Maisie, to get right there in time. Give her time, and she will arrive. She arrived in the case of Harrison. One morning, about a fortnight after the house match incident, Harrison awoke with a new sensation. At first he could not tell what exactly this sensation was, and being too sleepy to discuss nice points of internal emotion with himself, was just turning over with the intention of going to sleep again, when the truth flashed upon him. The sensation he felt was loneliness, and the reason he felt lonely was because he was the only occupant of the dormitory. To right and left and all around were empty beds.

As he mused drowsily on these portents, the distant sound of a bell came to his ears and completed the cure. It was the bell for chapel. He dragged his watch from under his pillow, and looked at it with consternation. Four minutes to seven. And chapel was at seven. Now Harrison had been late for chapel before. It was not the thought of missing the service that worried him. What really was serious was that he had been late so many times before that Merevale had hinted at serious steps to be taken if he were late again, or, at any rate, until a considerable interval of punctuality had elapsed.

That threat had been uttered only yesterday, and here he was in all probability late again.

There was no time to dress. He sprang out of bed, passed a sponge over his face as a concession to the decencies, and looked round for something to cover his night-shirt, which, however suitable for dormitory use, was, he felt instinctively, scarcely the garment to wear in public.

Fate seemed to fight for him. On one of the pegs in the wall hung a mackintosh, a large, blessed mackintosh. He was inside it in a moment.

Four minutes later he rushed into his place in chapel.

The short service gave him some time for recovering himself. He left the building feeling a new man. His costume, though quaint, would not call for comment. Chapel at St. Austin’s was never a full-dress ceremony. Mackintoshes covering night-shirts were the rule rather than the exception.

But between his costume and that of the rest there was this subtle distinction. They wore their own mackintoshes. He wore somebody else’s.

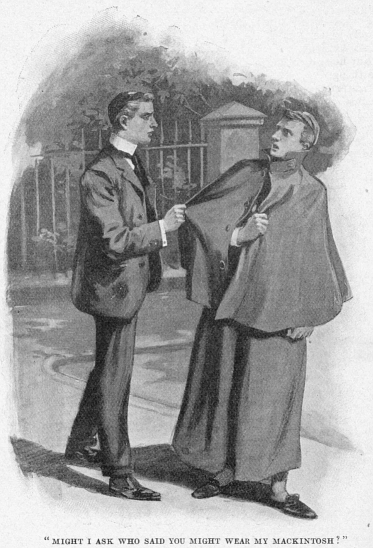

The bulk of the school had split up into sections, each section making for its own house, and Merevale’s was already within sight, when Harrison felt himself grasped from behind. He turned, to see Graham.

“Might I ask,” enquired Tony with great politeness, “who said you might wear my mackintosh?”

Harrison gasped.

“I suppose you didn’t know it was mine?”

“No, no, rather not. I didn’t know.”

“And if you had known it was mine you wouldn’t have taken it, I suppose?”

“Oh no, of course not,” said Harrison. Graham seemed to be taking an unexpectedly sensible view of the situation.

“Well,” said Tony, “now that you know it is mine, suppose you give it up.”

“Give it up!”

“Yes; buck up. It looks like rain, and I mustn’t catch cold.”

“But, Graham, I’ve only got on——”

“Spare us these delicate details. Mack up, please. I want it.”

Finally, Harrison appearing to be diffident in the matter, Tony took the garment off for him, and went on his way.

Harrison watched him go with mixed feelings. Righteous indignation struggled with the gravest apprehensions regarding his own future. If Merevale should see him! Horrible thought. He ran. He had just reached the house, and was congratulating himself on having escaped, when the worst happened. At the private entrance stood Merevale, and with him the headmaster himself. They both eyed him with considerable interest as he shot in at the boys’ entrance.

“Harrison,” said Merevale after breakfast.

“Yes, sir?”

“The headmaster wishes to see you—again.”

“Yes, sir,” said Harrison.

And there was a curious lack of enthusiasm in his voice.

Notes:

flannelled fools: See the notes to “Muddied Oafs” for this Kipling reference.

Sandford and Merton: from The History of Sandford and Merton by Thomas Day (1748–1789), which began as a short story, was expanded to book length in 1783, and continued in two further volumes in 1786 and 1789. It became a best-selling children’s book, incorporating Rousseau’s philosophy of education into a series of moral tales. Harry Sandford is the plain, honest son of a yeoman farmer; Tommy Merton begins as a spoiled, proud aristocrat, age six, pampered by his mother’s West Indies slaves; he learns the value of work and simple, virtuous pleasures from Harry.

Maisie: the 1900 Gaiety show The Messenger Boy included a song called “Maisie” by Lionel Monckton. (The lyrics were credited to Leslie Mayne, but that was a pseudonym for Monckton himself.) The chorus of the first verse has these words:

Maisie is a daisy,

Maisie is a dear;

For the boys are mad about her

And they can’t get on without her,

And they all cry “whoops” when Maisie’s coming near.

Maisie doesn’t mind it,

Maisie lets them stare;

Other girls are so uncertain

When they do a bit of flirting,

But Maisie gets right there.

Madame Eulalie’s Rare Plums

Madame Eulalie’s Rare Plums