The Captain, November 1902

OW

long the feud between Welch and his house-master Merevale had been going on is uncertain.

Probably it had started from a remark that Merevale made about Welch after the

final house-match of the previous summer, when, owing principally to his

mismanagement of the bowling—he was captain of Merevale’s—Perkins’ had won by a

wicket. Merevale was a quick-tempered man with a rather rich vein of sarcasm in

him, and his comment on Welch’s performance was pungent and personal. He

delivered it as the latter was coming up the pavilion steps after the match.

The pavilion was, as was usual on the final house-match day, packed with

lookers-on, all of whom heard the remark, and the majority of whom laughed

audibly. Nobody could be expected actually to enjoy this sort of thing, but

anybody else but Welch would have forgotten the incident next day. Welch,

however, was one of those people who, though they look as if they were morally

pachydermatous, really feel everything. He hated being laughed at. The result

was that he nursed his grievance against Merevale until it became a sort of

second nature to him to be at daggers drawn. That was the flaw in Welch’s

character, a character in other ways distinctly up to the average. He was

inclined to sulk in these sort of emergencies.

OW

long the feud between Welch and his house-master Merevale had been going on is uncertain.

Probably it had started from a remark that Merevale made about Welch after the

final house-match of the previous summer, when, owing principally to his

mismanagement of the bowling—he was captain of Merevale’s—Perkins’ had won by a

wicket. Merevale was a quick-tempered man with a rather rich vein of sarcasm in

him, and his comment on Welch’s performance was pungent and personal. He

delivered it as the latter was coming up the pavilion steps after the match.

The pavilion was, as was usual on the final house-match day, packed with

lookers-on, all of whom heard the remark, and the majority of whom laughed

audibly. Nobody could be expected actually to enjoy this sort of thing, but

anybody else but Welch would have forgotten the incident next day. Welch,

however, was one of those people who, though they look as if they were morally

pachydermatous, really feel everything. He hated being laughed at. The result

was that he nursed his grievance against Merevale until it became a sort of

second nature to him to be at daggers drawn. That was the flaw in Welch’s

character, a character in other ways distinctly up to the average. He was

inclined to sulk in these sort of emergencies.

It was now nearing the end of the Easter term, and the air was thick with sports and rumours of sports. Welch was a fine runner. The mile was his distance, though, like most milers, he also dabbled in the half. He had the easy springy stride which marks the runner with a future as distinguished from the runner who does great things at school but nothing afterwards.

The interest of a school in its sports is generally rather in the prospective times than in the actual struggle for first place. It usually happens that one runner is first favourite, while the rest enter principally for the look of the thing and the chance of second prize. It was so with the mile. Given anything but the worst of bad luck, a sprained ankle or a fall, for instance, Welch could not help winning it. It only remained to see whether he would do a record. The record for the mile at St. Austin’s was an exceptionally good one—four forty-four and a fifth. Mitchell-Jones, afterwards president of the O.U.A.C., and winner of many and various desirable trophies on the track, was responsible for it. He had done it in his last year at school, ten years before, and nobody had come near it since. A respectable four fifty-eight or nine was the average time. Last year Drake of Dacre’s house, with Thomson of Merevale’s a foot behind, had covered the distance, amidst tremendous enthusiasm, in four minutes and forty-eight seconds. It was generally felt that this had reached the high water-mark. Then rumours began to be spread abroad about Welch’s form. Two of the junior school had timed him surreptitiously before breakfast one morning, and he had done his mile in four forty-seven without turning a hair. In ordinary football clothes, too, not running clothes at all! The school allowed the usual discount necessary in dealing with junior school statements, and resolved to keep its eye on Welch. He ran a mile three times a week, always before breakfast. On the third day after the two juniors had made their report, several seniors, sportsmen in whose eyes sport ranked before sleep, got up early with reliable watches, and strolled about until Welch appeared. A little group formed at the scratch to see him off, several enthusiasts pacing him for the last lap. Three stop-watches of unimpeachable reputation agreed on four forty-five as the time. As there was still a week before the sports it seemed almost certain that he would be able to rub off the last remaining second of Mitchell-Jones’s time, and so hand his name down to eternal fame as the holder of the St. Austin’s mile record. The school was excited. Welch went to bed early on the night before the sports. He felt he owed it to the school to take no risks. For the past week Elliman’s had flowed like water, pastry had been regarded with an aversion that amounted to loathing, and Merevale had even gone to the length of allowing him toast instead of bread, a great concession. Welch thought this a very graceful act on Merevale’s part. He fell asleep that night wondering vaguely if he had not better make advances in the matter of the feud, and place matters once more on a peace footing.

He had been asleep four hours or more when he woke with a start. Somebody had entered his cubicle, and was shaking him by the shoulder. A hastily-formed impression that this was the advance guard of another dormitory making a midnight raid was dispelled by the rasping sound of a match on its box. Then it flared suddenly, and when his eyes had become accustomed to the light he saw that it was Merevale. Merevale, in pyjamas and a Balliol blazer, with a look on his face so ghastly that it woke Welch far more effectively than the shaking had done.

“Welch,” whispered Mr. Merevale, as the match gave a dying flicker.

“Yes, sir.”

“Get some clothes on. Get your running clothes on. Don’t make a noise. I don’t want the rest of the dormitory to wake. Then come to my study. And be quick. Don’t make a noise.”

He stole silently out again. Welch heard him open the door which separated his private house from the boys’ half. Then he began to dress in a dazed way, wondering all the time what was going to happen. It must be something important, or Merevale would hardly have dragged him out of bed like this at one o’clock. He had looked pretty bad, thought Welch. Why? And why running clothes? And why—a hundred things. Well, he would soon know.

He was not sorry to be out of the room and in the passage. There is always something very unpleasant and eerie in the sound of other people breathing heavily in the dark when one is awake oneself. Queer little moans and grunts and sighs were uttered from time to time as he groped for his running things and put them on. It was very cold, too. Altogether a most unpleasant situation. Why, why, why, he asked himself again.

Suddenly somebody began to talk in his sleep. The sound acted on Welch like an electric shock. He was surprised to find how near he had been to falling asleep again. He was quite awake now, and he made his way stealthily to Mr. Merevale’s study.

Merevale was waiting there for him. There was a candle burning on the table. It cast an indistinct light, and made the house-master’s face look worse than ever.

“Welch,” said he, “listen to me. Sit down. Now, in the first place, are you quite awake?”

This was exactly the question Welch had been asking of himself. Could he be awake?

“Yes, sir,” he said.

“Quite awake? Then listen to me. Welch, I am going to ask you to do rather a big thing. Do you know where Doctor Adamson lives?”

Adamson was the doctor who ministered to St. Austin’s when it was sick or when it thought it was. He lived in the village, and from St. Austin’s to the village is just a mile by road. The road is well laid, and as nearly level as a road can be.

“Yes, sir,” said Welch. He began to understand dimly.

“You could find the house in the dark? Good. Then listen. I want you to run your very hardest to Adamson’s and give him this note. Tell him to come at once. It’s important. Very important.”

Welch’s face became one large mark of interrogation. Mr. Merevale explained.

“Marjorie is very ill. Diphtheria, we think.”

Welch was on his feet in a moment at that. Marjorie was Merevale’s ten-year-old daughter. The house worshipped her to a man, and with reason, for the Mere Kid, as she was called, was a patriot and sportswoman to her small finger-tips, and wore out vast supplies of gloves annually in applauding the doings of her house in the cricket and football fields.

“Your bicycle, sir?” he said.

“Punctured yesterday. Not another in the house.” Welch was silent.

“Can you do it in time? In another quarter of an hour it may be too late.”

Welch did what every other member of the house would have done. He held out his hand for the note.

“It’s just twenty-five past,” said Merevale, as he let him out of the front door. “Can you get there by half-past?”

“Easily, sir,” said Welch, and started.

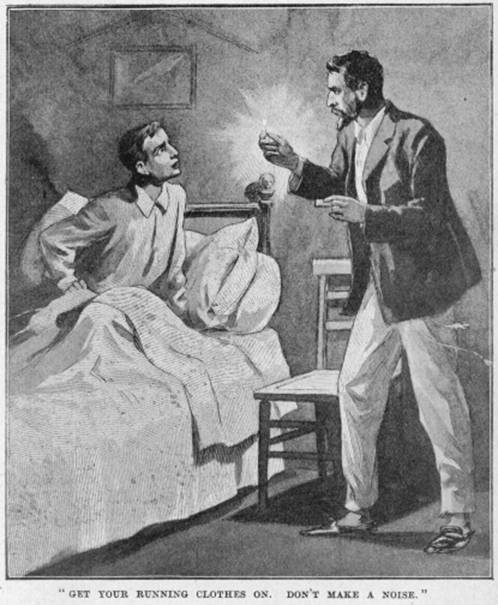

Doctor Adamson was returning from a night visit to a patient, when, just as he reached the door of his house, he pulled up in blank astonishment. Down the road to the left, from the direction of St. Austin’s, a white figure was running at an extraordinary pace. The doctor’s professional ear recognised the heavy breathing of a fine trained runner who has all but run himself out. For a moment he was profoundly puzzled.

“Training! At this time of night! Can’t be. By jove, he’s making for my house. Must be something wrong.”

“Here,” he shouted, “this way. I am Doctor Adamson, if you are after me.”

Welch wheeled round in the direction of the voice, and staggered up to the dogcart. “Note,” he gasped, “Merevale.” He was terribly tired in spite of his training. “Time?” he gasped.

The doctor whipped out his watch.

“The exact time is eighteen seconds to the half-hour. Half-past one practically. Now, let’s see what it’s all about.”

He frowned as he read Merevale’s letter. “Diphtheria. H’m. Thinks it’s diphtheria. Can’t be anything else by the symptoms. Jump up, young man. We must hurry.”

But Welch could not move. He lay by the side of the road and panted. The doctor was a powerful man. He sprang down, and lifted him in his arms. It took him two minutes to carry him into the house and place him on a sofa. Then he returned to the dogcart. He gathered up the reins again and turned the horse’s head towards St. Austin’s.

Merevale was standing at the front door.

“That you, doctor?” he said. “Thank God you were in. Come on quickly, man. She’s worse.”

“How about the horse?” asked the doctor. “He won’t improve the flower beds if he gets on to them.”

“Never mind the flower beds. Let the beast roll in them if he wants to. This way.”

Doctor Adamson rose from his inspection of the patient, and turned to Merevale with a smile. “I think it will be all right,” he said, “I am in time by exactly five minutes.”

* * * * *

“I must be going back to my other patient now,” said the doctor an hour afterwards.

“Your other patient?”

“The runner.”

“Oh, Welch.”

“Welch is his name, is it? I used to know some Welches in Somersetshire. Wonder if it is the same family. I suppose you realise what you owe to him?”

“Yes, by jove,” said Mr. Merevale. “If you will give me a lift, doctor, I’ll come back with you now and see him.”

Welch did not break the record on sports day, as he was too knocked up to run at all, and the race went to Roberts, of Dacre’s house, in the very mediocre time of five one. But he has the satisfaction of knowing that in his run that night he must have been a clear second inside Mitchell-Jones’s historic time, making all allowances. The occasion is also kept green in his memory by a silver cup, the exact double of the school mile cup, which Merevale presented to him as a memento of the occasion.

Welch did better times after he left school, but, as he very justly observes, that was the best mile he ever did, or was ever likely to do.

And Merevale is of much the same opinion.

Madame Eulalie’s Rare Plums

Madame Eulalie’s Rare Plums