The Captain, October 1908

CHAPTER I.

mr. bickersdyke walks behind the bowler’s arm.

ONSIDERING what a

prominent figure Mr. John Bickersdyke was to be in Mike Jackson’s life, it was

only appropriate that he should make a dramatic entry into it. This he did, by

walking behind the bowler’s arm when Mike had scored ninety-eight, causing him

thereby to be clean bowled by a long-hop.

ONSIDERING what a

prominent figure Mr. John Bickersdyke was to be in Mike Jackson’s life, it was

only appropriate that he should make a dramatic entry into it. This he did, by

walking behind the bowler’s arm when Mike had scored ninety-eight, causing him

thereby to be clean bowled by a long-hop.

It was the last day of the Ilsworth cricket week, and the house team were struggling hard on a damaged wicket. During the first two matches of the week all had been well. Warm sunshine, true wickets, tea in the shade of the trees. But on the Thursday night, as the team champed their dinner contentedly after defeating the Incogniti by two wickets, a pattering of rain made itself heard upon the windows. By bedtime it had settled to a steady downpour. On Friday morning, when the team of the local regiment arrived in their brake, the sun was shining once more in a watery, melancholy way, but play was not possible before lunch. After lunch the bowlers were in their element. The regiment, winning the toss, put together a hundred and thirty, due principally to a last wicket stand between two enormous corporals, who swiped at everything and had luck enough for two whole teams. The house team followed with seventy-eight, of which Psmith, by his usual golf methods, claimed thirty. Mike, who had gone in first, as the star bat of the side, had been run out with great promptitude off the first ball of the innings, which his partner had hit in the immediate neighbourhood of point. At close of play the regiment had made five without loss. This, on the Saturday morning, helped by another shower of rain which made the wicket easier for the moment, they had increased to a hundred and forty-eight, leaving the house just two hundred to make on a pitch which looked as if it were made of linseed.

It was during this week that Mike had first made the acquaintance of Psmith’s family. Mr. Smith had moved from Shropshire, and taken Ilsworth Hall in a neighbouring county. This he had done, as far as could be ascertained, simply because he had a poor opinion of Shropshire cricket. And just at the moment cricket happened to be the pivot of his life.

“My father,” Psmith had confided to Mike, meeting him at the station in the family motor on the Monday, “is a man of vast but volatile brain. He has not that calm, dispassionate outlook on life which marks your true philosopher, such as myself. I——”

“I say,” interrupted Mike, eyeing Psmith’s movements with apprehension, “you aren’t going to drive, are you?”

“Who else? As I was saying, I am like some contented spectator of a Pageant. My pater wants to jump in and stage-manage. He is a man of hobbies. He never has more than one at a time, and he never has that long. But while he has it, it’s all there. When I left the house this morning he was all for cricket. But by the time we get to the ground he may have chucked cricket and taken up the Territorial Army. Don’t be surprised if you find the wicket being dug up into trenches, when we arrive, and the pro. moving in echelon towards the pavilion. No,” he added, as the car turned into the drive, and they caught a glimpse of white flannels and blazers in the distance, and heard the sound of bat meeting ball, “cricket seems still to be topping the bill. Come along, and I’ll show you your room. It’s next to mine, so that, if brooding on Life in the still hours of the night, I hit on any great truth, I shall pop in and discuss it with you.”

While Mike was changing, Psmith sat on his bed, and continued to discourse.

“I suppose you’re going to the ’Varsity?” he said.

“Rather,” said Mike, lacing his boots. “You are, of course? Cambridge, I hope. I’m going to King’s.”

“Between ourselves,” confided Psmith, “I’m dashed if I know what’s going to happen to me. I am the thingummy of what’s-its-name.”

“You look it,” said Mike, brushing his hair.

“Don’t stand there cracking the glass,” said Psmith. “I tell you I am practically a human three-shies-a-penny ball. My father is poising me lightly in his hand, preparatory to flinging me at one of the milky cocos of Life. Which one he’ll aim at I don’t know. The least thing fills him with a whirl of new views as to my future. Last week we were out shooting together, and he said that the life of the gentleman-farmer was the most manly and independent on earth, and that he had a good mind to start me on that. I pointed out that lack of early training had rendered me unable to distinguish between a threshing-machine and a mangel-wurzel, so he chucked that. He has now worked round to Commerce. It seems that a blighter of the name of Bickersdyke is coming here for the week-end next Saturday. As far as I can say without searching the Newgate Calendar, the man Bickersdyke’s career seems to have been as follows. He was at school with my pater, went into the City, raked in a certain amount of doubloons—probably dishonestly—and is now a sort of Captain of Industry, manager of some bank or other, and about to stand for Parliament. The result of these excesses is that my pater’s imagination has been fired, and at time of going to press he wants me to imitate Comrade Bickersdyke. However, there’s plenty of time. That’s one comfort. He’s certain to change his mind again. Ready? Then suppose we filter forth into the arena?”

Out on the field Mike was introduced to the man of hobbies. Mr. Smith, senior, was a long, earnest-looking man who might have been Psmith in a grey wig but for his obvious energy. He was as wholly on the move as Psmith was wholly statuesque. Where Psmith stood like some dignified piece of sculpture, musing on deep questions with a glassy eye, his father would be trying to be in four places at once. When Psmith presented Mike to him, he shook hands warmly with him and started a sentence, but broke off in the middle of both performances to dash wildly in the direction of the pavilion in an endeavour to catch an impossible catch some thirty yards away. The impetus so gained carried him on towards Bagley, the Ilsworth Hall ground-man, with whom a moment later he was carrying on an animated discussion as to whether he had or had not seen a dandelion on the field that morning. Two minutes afterwards he had skimmed away again. Mike, as he watched him, began to appreciate Psmith’s reasons for feeling some doubt as to what would be his future walk in life.

At lunch that day Mike sat next to Mr. Smith, and improved his acquaintance with him; and by the end of the week they were on excellent terms. Psmith’s father had Psmith’s gift of getting on well with people.

On this Saturday, as Mike buckled on his pads, Mr. Smith bounded up, full of advice and encouragement.

“My boy,” he said, “we rely on you. These others”—he indicated with a disparaging wave of the hand the rest of the team, who were visible through the window of the changing-room—”are all very well. Decent club bats. Good for a few on a billiard-table. But you’re our hope on a wicket like this. I have studied cricket all my life”—till that summer it is improbable that Mr. Smith had ever handled a bat—“and I know a first-class batsman when I see one. I’ve seen your brothers play. Pooh, you’re better than any of them. That century of yours against the Green Jackets was a wonderful innings, wonderful. Now look here, my boy. I want you to be careful. We’ve a lot of runs to make, so we mustn’t take any risks. Hit plenty of boundaries, of course, but be careful. Careful. Dash it, there’s a youngster trying to climb up the elm. He’ll break his neck. It’s young Giles, my keeper’s boy. Hi! Hi, there!”

He scudded out to avert the tragedy, leaving Mike to digest his expert advice on the art of batting on bad wickets.

Possibly it was the excellence of this advice which induced Mike to play what was, to date, the best innings of his life. There are moments when the batsman feels an almost superhuman fitness. This came to Mike now. The sun had begun to shine strongly. It made the wicket more difficult, but it added a cheerful touch to the scene. Mike felt calm and masterful. The bowling had no terrors for him. He scored nine off his first over and seven off his second, half-way through which he lost his partner. He was to undergo a similar bereavement several times that afternoon, and at frequent intervals. However simple the bowling might seem to him, it had enough sting in it to worry the rest of the team considerably. Batsmen came and went at the other end with such rapidity that it seemed hardly worth while their troubling to come in at all. Every now and then one would give promise of better things by lifting the slow bowler into the pavilion or over the boundary, but it always happened that a similar stroke, a few balls later, ended in an easy catch. At five o’clock the Ilsworth score was eighty-one for seven wickets, last man nought, Mike not out fifty-nine. As most of the house team, including Mike, were dispersing to their homes or were due for visits at other houses that night, stumps were to be drawn at six. It was obvious that they could not hope to win. Number nine on the list, who was Bagley, the ground-man, went in with instructions to play for a draw, and minute advice from Mr. Smith as to how he was to do it. Mike had now begun to score rapidly, and it was not to be expected that he could change his game; but Bagley, a dried-up little man of the type which bowls for five hours on a hot August day without exhibiting any symptoms of fatigue, put a much-bound bat stolidly in front of every ball he received; and the Hall’s prospects of saving the game grew brighter.

At a quarter to six the professional left, caught at very silly point for eight. The score was a hundred and fifteen, of which Mike had made eighty-five.

A lengthy young man with yellow hair, who had done some good fast bowling for the Hall during the week, was the next man in. In previous matches he had hit furiously at everything, and against the Green Jackets had knocked up forty in twenty minutes while Mike was putting the finishing-touches to his century. Now, however, with his host’s warning ringing in his ears, he adopted the unspectacular, or Bagley, style of play. His manner of dealing with the ball was that of one playing croquet. He patted it gingerly back to the bowler when it was straight, and left it icily alone when it was off the wicket. Mike, still in the brilliant vein, clumped a half-volley past point to the boundary, and with highly scientific late cuts and glides brought his score to ninety-eight. With Mike’s score at this, the total at a hundred and thirty, and the hands of the clock at five minutes to six, the yellow-haired croquet exponent fell, as Bagley had fallen, a victim to silly point, the ball being the last of the over.

Mr. Smith, who always went in last for his side, and who so far had not received a single ball during the week, was down the pavilion steps and half-way to the wicket before the retiring batsman had taken half a dozen steps.

“Last over,” said the wicket-keeper to Mike. “Any idea how many you’ve got? You must be near your century, I should think.”

“Ninety-eight,” said Mike. He always counted his runs.

“By Jove, as near as that? This is something like a finish.”

Mike left the first ball alone, and the second. They were too wide of the off-stump to be hit at safely. Then he felt a thrill as the third ball left the bowler’s hand. It was a long-hop. He faced square to pull it.

And at that moment Mr. John Bickersdyke walked into his life across the bowling-screen.

He crossed the bowler’s arm just before the ball pitched. Mike lost sight of it for a fraction of a second, and hit wildly. The next moment his leg stump was askew; and the Hall had lost the match.

“I’m sorry,” he said to Mr. Smith. “Some silly idiot walked across the screen just as the ball was bowled.”

“What!” shouted Mr. Smith. “Who was the fool who walked behind the bowler’s arm?” he yelled appealingly to Space.

“Here he comes, whoever he is,” said Mike.

A short, stout man in a straw hat and a flannel suit was walking towards them. As he came nearer Mike saw that he had a hard, thin-lipped mouth, half-hidden by a rather ragged moustache, and that behind a pair of gold spectacles were two pale and slightly protruding eyes, which, like his mouth, looked hard.

“How are you, Smith?” he said.

“Hullo, Bickersdyke.” There was a slight internal struggle, and then Mr. Smith ceased to be the cricketer and became the host. He chatted amiably to the new-comer.

“You lost the game, I suppose,” said Mr. Bickersdyke.

The cricketer in Mr. Smith came to the top again, blended now, however, with the host. He was annoyed, but restrained in his annoyance.

“I say, Bickersdyke, you know, my dear fellow,” he said complainingly, “you shouldn’t have walked across the screen. You put Jackson off, and made him get bowled.”

“The screen?”

“That curious white object,” said Mike. “It is not put up merely as an ornament. There’s a sort of rough idea of giving the batsman a chance of seeing the ball, as well. It’s a great help to him when people come charging across it just as the bowler bowls.”

Mr. Bickersdyke turned a slightly deeper shade of purple, and was about to reply, when what sporting reporters call “the veritable ovation” began.

Quite a large crowd had been watching the game, and they expressed their approval of Mike’s performance.

There is only one thing for a batsman to do on these occasions. Mike ran into the pavilion, leaving Mr. Bickersdyke standing.

CHAPTER II.

mike hears bad news.

T seemed to Mike,

when he got home, that there was a touch of gloom in the air. His sisters were

as glad to see him as ever. There was a good deal of rejoicing going on among

the female Jacksons because Joe had scored his first double century in

first-class cricket. Double centuries are too common nowadays for the papers

to take much notice of them; but, still, it is not everybody who can make them,

and the occasion was one to be marked. Mike had read the news in the evening

paper in the train, and had sent his brother a wire from the station,

congratulating him. He had wondered whether he himself would ever achieve the

feat in first-class cricket. He did not see why he should not. He looked

forward through a long vista of years of county cricket. He had a birth

qualification for the county in which Mr. Smith had settled, and he had played

for it once already at the beginning of the holidays. His début had not

been sensational, but it had been promising. The fact that two members of the

team had made centuries, and a third seventy odd, had rather eclipsed his own

twenty-nine not out; but it had been a faultless innings, and nearly all the

papers had said that here was yet another Jackson, evidently well up to the

family standard, who was bound to do big things in the future.

T seemed to Mike,

when he got home, that there was a touch of gloom in the air. His sisters were

as glad to see him as ever. There was a good deal of rejoicing going on among

the female Jacksons because Joe had scored his first double century in

first-class cricket. Double centuries are too common nowadays for the papers

to take much notice of them; but, still, it is not everybody who can make them,

and the occasion was one to be marked. Mike had read the news in the evening

paper in the train, and had sent his brother a wire from the station,

congratulating him. He had wondered whether he himself would ever achieve the

feat in first-class cricket. He did not see why he should not. He looked

forward through a long vista of years of county cricket. He had a birth

qualification for the county in which Mr. Smith had settled, and he had played

for it once already at the beginning of the holidays. His début had not

been sensational, but it had been promising. The fact that two members of the

team had made centuries, and a third seventy odd, had rather eclipsed his own

twenty-nine not out; but it had been a faultless innings, and nearly all the

papers had said that here was yet another Jackson, evidently well up to the

family standard, who was bound to do big things in the future.

The touch of gloom was contributed by his brother Bob to a certain extent, and by his father more noticeably. Bob looked slightly thoughtful. Mr. Jackson seemed thoroughly worried.

Mike approached Bob on the subject in the billiard-room after dinner. Bob was practising cannons in rather a listless way.

“What’s up, Bob?” asked Mike.

Bob laid down his cue.

“I’m hanged if I know,” said Bob. “Something seems to be. Father’s worried about something.”

“He looked as if he’d got the hump rather at dinner.”

“I only got here this afternoon, about three hours before you did. I had a bit of a talk with him before dinner. I can’t make out what’s up. He seemed awfully keen on my finding something to do now I’ve come down from Oxford. Wanted to know whether I couldn’t get a tutoring job or a mastership at some school next term. I said I’d have a shot. I don’t see what all the hurry’s about, though. I was hoping he’d give me a bit of travelling on the Continent somewhere before I started in.”

“Rough luck,” said Mike. “I wonder why it is. Jolly good about Joe, wasn’t it. Let’s have fifty up, shall we?”

Bob’s remarks had given Mike no hint of impending disaster. It seemed strange, of course, that his father, who had always been so easy-going, should have developed a hustling Get On or Get Out spirit, and be urging Bob to Do It Now; but it never occurred to him that there could be any serious reason for it. After all, fellows had to start working some time or other. Probably his father had merely pointed this out to Bob, and Bob had made too much of it.

Half-way through the game Mr. Jackson entered the room, and stood watching in silence.

“Want a game, father?” asked Mike.

“No, thanks, Mike. What is it? A hundred up?”

“Fifty.”

“Oh, then you’ll be finished in a moment. When you are, I wish you’d just look into the study for a moment, Mike. I want to have a talk with you.”

“Rum,” said Mike, as the door closed. “I wonder what’s up?”

For a wonder his conscience was free. It was not as if a bad school-report might have arrived in his absence. His Sedleigh report had come at the beginning of the holidays, and had been, on the whole, fairly decent—nothing startling either way. Mr. Downing, perhaps through remorse at having harried Mike to such an extent during the Sammy episode, had exercised a studied moderation in his remarks. He had let Mike down far more easily than he really deserved. So it could not be a report that was worrying Mr. Jackson. And there was nothing else on his conscience.

Bob made a break of sixteen, and ran out. Mike replaced his cue, and walked to the study.

His father was sitting at the table. Except for the very important fact that this time he felt that he could plead Not Guilty on every possible charge, Mike was struck by the resemblance in the general arrangement of the scene to that painful ten minutes at the end of the previous holidays, when his father had announced his intention of taking him away from Wrykyn and sending him to Sedleigh. The resemblance was increased by the fact that, as Mike entered, Mr. Jackson was kicking at the waste-paper basket—a thing which with him was an infallible sign of mental unrest.

“Sit down, Mike,” said Mr. Jackson. “How did you get on during the week?”

“Topping. Only once out under double figures. And then I was run out. Got a century against the Green Jackets, seventy-one against the Incogs, and to-day I made ninety-eight on a beast of a wicket, and only got out because some silly goat of a chap——”

He broke off. Mr. Jackson did not seem to be attending. There was a silence. Then Mr. Jackson spoke with an obvious effort.

“Look here, Mike, we’ve always understood one another, haven’t we?”

“Of course we have.”

“You know I wouldn’t do anything to prevent you having a good time, if I could help it. I took you away from Wrykyn, I know, but that was a special case. It was necessary. But I understand perfectly how keen you are to go to Cambridge, and I wouldn’t stand in the way for a minute, if I could help it.”

Mike looked at him blankly. This could only mean one thing. He was not to go to the ’Varsity. But why? What had happened? When he had left for the Smith’s cricket week, his name had been down for King’s, and the whole thing settled. What could have happened since then?

“But I can’t help it,” continued Mr. Jackson.

“Aren’t I going up to Cambridge, father?” stammered Mike.

“I’m afraid not, Mike. I’d manage it if I possibly could. I’m just as anxious to see you get your Blue as you are to get it. But it’s kinder to be quite frank. I can’t afford to send you to Cambridge. I won’t go into details which you would not understand; but I have lost a very large sum of money since I saw you last. So large that we shall have to economise in every way. I shall let this house and take a much smaller one. And you and Bob, I’m afraid, will have to start earning your living. I know it’s a terrible disappointment to you, old chap.”

“Oh, that’s all right,” said Mike thickly. There seemed to be something sticking in his throat, preventing him from speaking.

“If there was any possible way——”

“No, it’s all right, father, really. I don’t mind a bit. It’s awfully rough luck on you losing all that.”

There was another silence. The clock ticked away energetically on the mantelpiece, as if glad to make itself heard at last. Outside, a plaintive snuffle made itself heard. John, the bull-dog, Mike’s inseparable companion, who had followed him to the study, was getting tired of waiting on the mat. Mike got up, and opened the door. John lumbered in.

The movement broke the tension.

“Thanks, Mike,” said Mr. Jackson, as Mike started to leave the room, “you’re a sportsman.”

CHAPTER III.

the new era begins.

ETAILS of what were

in store for him were given to Mike next morning. During his absence at

Ilsworth a vacancy had been got for him in that flourishing institution, the

New Asiatic Bank; and he was to enter upon his duties, whatever they might be,

on the Tuesday of the following week. It was short notice, but banks have a

habit of swallowing their victims rather abruptly. Mike remembered the case of

Wyatt, who had had just about the same amount of time in which to get used to

the prospect of Commerce.

ETAILS of what were

in store for him were given to Mike next morning. During his absence at

Ilsworth a vacancy had been got for him in that flourishing institution, the

New Asiatic Bank; and he was to enter upon his duties, whatever they might be,

on the Tuesday of the following week. It was short notice, but banks have a

habit of swallowing their victims rather abruptly. Mike remembered the case of

Wyatt, who had had just about the same amount of time in which to get used to

the prospect of Commerce.

On the Monday morning a letter arrived from Psmith. Psmith was still perturbed. “Commerce,” he wrote, “continues to boom. My pater referred to Comrade Bickersdyke last night as a Merchant Prince. Comrade B. and I do not get on well together. Purely for his own good, I drew him aside yesterday and explained to him at great length the frightfulness of walking across the bowling-screen. He seemed restive, but I was firm. We parted rather with the Distant Stare than the Friendly Smile. But I shall persevere. In many ways the casual observer would say that he was hopeless. He is a poor performer at Bridge, as I was compelled to hint to him on Saturday night. His eyes have no animated sparkle of intelligence. And the cut of his clothes jars my sensitive soul to its foundations. I don’t wish to speak ill of a man behind his back, but I must confide in you, as my Boyhood’s Friend, that he wore a made-up tie at dinner. But no more of a painful subject. I am working away at him with a brave smile. Sometimes I think that I am succeeding. Then he seems to slip back again. However,” concluded the letter, ending on an optimistic note, “I think that I shall make a man of him yet—some day.”

Mike re-read this letter in the train that took him to London. By this time Psmith would know that his was not the only case in which Commerce was booming. Mike had written to him by return, telling him of the disaster which had befallen the house of Jackson. Mike wished he could have told him in person, for Psmith had a way of treating unpleasant situations as if he were merely playing at them for his own amusement. Psmith’s attitude towards the slings and arrows of outrageous Fortune was to regard them with a bland smile, as if they were part of an entertainment got up for his express benefit.

Arriving at Paddington, Mike stood on the platform, waiting for his box to emerge from the luggage-van, with mixed feelings of gloom and excitement. The gloom was in the larger quantities, perhaps, but the excitement was there, too. It was the first time in his life that he had been entirely dependent on himself. He had crossed the Rubicon. The occasion was too serious for him to feel the same helplessly furious feeling with which he had embarked on life at Sedleigh. It was possible to look on Sedleigh with quite a personal enmity. London was too big to be angry with. It took no notice of him. It did not care whether he was glad to be there or sorry, and there was no means of making it care. That is the peculiarity of London. There is a sort of cold unfriendliness about it. A city like New York makes the new arrival feel at home in half an hour; but London is a specialist in what Psmith in his letter had called the Distant Stare. You have to buy London’s good-will.

Mike drove across the Park to Victoria, feeling very empty and small. He had settled on Dulwich as the spot to get lodgings, partly because, knowing nothing about London, he was under the impression that rooms anywhere inside the four-mile radius were very expensive, but principally because there was a school at Dulwich, and it would be a comfort being near a school. He might get a game of fives there sometimes, he thought, on a Saturday afternoon, and, in the summer, occasional cricket.

Wandering at a venture up the asphalt passage which leads from Dulwich station in the direction of the College, he came out into Acacia Road. There is something about Acacia Road which inevitably suggests furnished apartments. A child could tell at a glance that it was bristling with bed-sitting rooms.

Mike knocked at the first door over which a card hung.

There is probably no more depressing experience in the world than the process of engaging furnished apartments. Those who let furnished apartments seem to take no joy in the act. Like Pooh-Bah, they do it, but it revolts them.

In answer to Mike’s knock, a female person opened the door. In appearance she resembled a pantomime “dame,” inclining towards the restrained melancholy of Mr. Wilkie Bard rather than the joyous abandon of Mr. George Robey. Her voice she had modelled on the gramophone. Her most recent occupation seemed to have been something with a good deal of yellow soap in it. As a matter of fact—there are no secrets between our readers and ourselves—she had been washing a shirt. A useful occupation, and an honourable, but one that tends to produce a certain homeliness in the appearance.

She wiped a pair of steaming hands on her apron, and regarded Mike with an eye which would have been markedly expressionless in a boiled fish.

“Was there anything?” she asked.

Mike felt that he was in for it now. He had not sufficient ease of manner to back gracefully away and disappear, so he said that there was something. In point of fact, he wanted a bed-sitting room.

“Orkup stays,” said the pantomime dame. Which Mike interpreted to mean, would he walk upstairs?

The procession moved up a dark flight of stairs until it came to a door. The pantomime dame opened this, and shuffled through. Mike stood in the doorway, and looked in.

It was a repulsive room. One of those characterless rooms which are only found in furnished apartments. To Mike, used to the comforts of his bedroom at home and the cheerful simplicity of a school dormitory, it seemed about the most dismal spot he had ever struck. A sort of Sargasso Sea among bedrooms.

He looked round in silence. Then he said: “Yes.” There did not seem much else to say.

“It’s a nice room,” said the pantomime dame. Which was a black lie. It was not a nice room. It never had been a nice room. And it did not seem at all probable that it ever would be a nice room. But it looked cheap. That was the great thing. Nobody could have the assurance to charge much for a room like that. A landlady with a conscience might even have gone to the length of paying people some small sum by way of compensation to them for sleeping in it.

“About what?” queried Mike. Cheapness was the great consideration. He understood that his salary at the bank would be about four pounds ten a month, to begin with, and his father was allowing him five pounds a month. One does not do things en prince on a hundred and fourteen pounds a year.

The pantomime dame became slightly more animated. Prefacing her remarks by a repetition of her statement that it was a nice room, she went on to say that she could “do” it at seven and sixpence per week “for him”—giving him to understand, presumably, that, if the Shah of Persia or Mr. Carnegie ever applied for a night’s rest, they would sigh in vain for such easy terms. And that included lights. Coals were to be looked on as an extra. “Sixpence a scuttle.” Attendance was thrown in.

Having stated these terms, she dribbled a piece of fluff under the bed, after the manner of a professional Association footballer, and relapsed into her former moody silence.

Mike said he thought that would be all right. The pantomime dame exhibited no pleasure.

“ ’Bout meals?” she said. “You’ll be wanting breakfast. Bacon, aigs, an’ that, I suppose?”

Mike said he supposed so.

“That’ll be extra,” she said. “And dinner? A chop, or a nice steak?”

Mike bowed before this original flight of fancy. A chop or a nice steak seemed to be about what he might want.

“That’ll be extra,” said the pantomime dame in her best Wilkie Bard manner.

Mike said yes, he supposed so. After which, having put down seven and sixpence, one week’s rent in advance, he was presented with a grubby receipt and an enormous latchkey, and the séance was at an end.

Mike wandered out of the house. A few steps took him to the railings that bounded the College grounds. It was late August, and the evenings had begun to close in. The cricket-field looked very cool and spacious in the dim light, with the school buildings looming vague and shadowy through the slight mist. The little gate by the railway bridge was not locked. He went in, and walked slowly across the turf towards the big clump of trees which marked the division between the cricket and football fields. It was all very pleasant and soothing after the pantomime dame and her stuffy bed-sitting room. He sat down on a bench beside the second eleven telegraph-board, and looked across the ground at the pavilion. For the first time that day he began to feel really home-sick. Up till now the excitement of a strange venture had borne him up; but the cricket-field and the pavilion reminded him so sharply of Wrykyn. They brought home to him with a cutting distinctness, the absolute finality of his break with the old order of things. Summers would come and go, matches would be played on this ground with all the glory of big scores and keen finishes; but he was done. “He was a jolly good bat at school. Top of the Wrykyn averages two years. But didn’t do anything after he left. Went into the city or something.” That was what they would say of him, if they didn’t quite forget him.

The clock on the tower over the senior block chimed quarter after quarter, but Mike sat on, thinking. It was quite late when he got up, and began to walk back to Acacia Road. He felt cold and stiff and very miserable.

CHAPTER IV.

first steps in a business career.

HE City received Mike

with the same aloofness with which the more western portion of London had

welcomed him on the previous day. Nobody seemed to look at him. He was

permitted to alight at St. Paul’s and make his way up Queen Victoria Street

without any demonstration. He followed the human stream till he reached the

Mansion House, and eventually found himself at the massive building of the New

Asiatic Bank, Limited.

HE City received Mike

with the same aloofness with which the more western portion of London had

welcomed him on the previous day. Nobody seemed to look at him. He was

permitted to alight at St. Paul’s and make his way up Queen Victoria Street

without any demonstration. He followed the human stream till he reached the

Mansion House, and eventually found himself at the massive building of the New

Asiatic Bank, Limited.

The difficulty now was to know how to make an effective entrance. There was the bank, and here was he. How had he better set about breaking it to the authorities that he had positively arrived and was ready to start earning his four pound ten per mensem? Inside, the bank seemed to be in a state of some confusion. Men were moving about in an apparently irresolute manner. Nobody seemed actually to be working. As a matter of fact, the business of a bank does not start very early in the morning. Mike had arrived before things had really begun to move. As he stood near the doorway, one or two panting figures rushed up the steps, and flung themselves at a large book which stood on the counter near the door. Mike was to come to know this book well. In it, if you were an employé of the New Asiatic Bank, you had to inscribe your name every morning. It was removed at ten sharp to the accountant’s room, and if you reached the bank a certain number of times in the year too late to sign, bang went your bonus.

After a while things began to settle down. The stir and confusion gradually ceased. All down the length of the bank, figures could be seen, seated on stools and writing hieroglyphics in large ledgers. A benevolent-looking man, with spectacles and a straggling grey beard, crossed the gangway close to where Mike was standing. Mike put the thing to him, as man to man.

“Could you tell me,” he said, “what I’m supposed to do? I’ve just joined the bank.” The benevolent man stopped, and looked at him with a pair of mild blue eyes. “I think, perhaps, that your best plan would be to see the manager,” he said. “Yes, I should certainly do that. He will tell you what work you have to do. If you will permit me, I will show you the way.”

“It’s awfully good of you,” said Mike. He felt very grateful. After his experience of London, it was a pleasant change to find someone who really seemed to care what happened to him. His heart warmed to the benevolent man.

“It feels strange to you, perhaps, at first, Mr.——”

“Jackson.”

“Mr. Jackson. My name is Waller. I have been in the City some time, but I can still recall my first day. But one shakes down. One shakes down quite quickly. Here is the manager’s room. If you go in, he will tell you what to do.”

“Thanks awfully,” said Mike.

“Not at all.” He ambled off on the quest which Mike had interrupted, turning, as he went, to bestow a mild smile of encouragement on the new arrival. There was something about Mr. Waller which reminded Mike pleasantly of the White Knight in “Alice through the Looking-glass.”

Mike knocked at the managerial door, and went in.

Two men were sitting at the table. The one facing the door was writing when Mike went in. He continued to write all the time he was in the room. Conversation between other people in his presence had apparently no interest for him, nor was it able to disturb him in any way.

The other man was talking into a telephone. Mike waited till he had finished. Then he coughed. The man turned round. Mike had thought, as he looked at his back and heard his voice, that something about his appearance or his way of speaking was familiar. He was right. The man in the chair was Mr. Bickersdyke, the cross-screen pedestrian.

These reunions are very awkward. Mike was frankly unequal to the situation. Psmith, in his place, would have opened the conversation, and relaxed the tension with some remark on the weather or the state of the crops. Mike merely stood wrapped in silence, as in a garment.

That the recognition was mutual was evident from Mr. Bickersdyke’s look. But apart from this, he gave no sign of having already had the pleasure of making Mike’s acquaintance. He merely stared at him as if he were a blot on the arrangement of the furniture, and said, “Well?”

The most difficult parts to play in real life as well as on the stage are those in which no “business” is arranged for the performer. It was all very well for Mr. Bickersdyke. He had been “discovered sitting.” But Mike had had to enter, and he wished now that there was something he could do instead of merely standing and speaking.

“I’ve come,” was the best speech he could think of. It was not a good speech. It was too sinister. He felt that even as he said it. It was the sort of thing Mephistopheles would have said to Faust by way of opening conversation. And he was not sure, either, whether he ought not to have added, “sir.”

Apparently such subtleties of address were not necessary, for Mr. Bickersdyke did not start up and shout, “This language to me!” or anything of that kind. He merely said, “Oh! And who are you?”

“Jackson,” said Mike. It was irritating, this assumption on Mr. Bickersdyke’s part that they had never met before.

“Jackson? Ah, yes. You have joined the staff?”

Mike rather liked this way of putting it. It lent a certain dignity to the proceedings, making him feel like some important person for whose services there had been strenuous competition. He seemed to see the bank’s directors being reassured by the chairman. (“I am happy to say, gentlemen, that our profits for the past year are £3,000,006-2-2½ —(cheers)—and”—impressively—“that we have finally succeeded in inducing Mr. Mike Jackson—(sensation)—to—er—in fact, to join the staff!” (Frantic cheers, in which the chairman joined.)”

“Yes,” he said.

Mr. Bickersdyke pressed a bell on the table beside him, and picking up a pen, began to write. Of Mike he took no further notice, leaving that toy of Fate standing stranded in the middle of the room.

After a few moments one of the men in fancy dress, whom Mike had seen hanging about the gangway, and whom he afterwards found to be messengers, appeared. Mr. Bickersdyke looked up.

“Ask Mr. Bannister to step this way,” he said.

The messenger disappeared, and presently the door opened again to admit a shock-headed youth with paper cuff-protectors round his wrists.

“This is Mr. Jackson, a new member of the staff. He will take your place in the postage department. You will go into the cash department, under Mr. Waller. Kindly show him what he has to do.”

Mike followed Mr. Bannister out. On the other side of the door the shock-headed one became communicative.

“Whew!” he said, mopping his brow. “That’s the sort of thing which gives me the pip. When William came and said old Bick wanted to see me, I said to him, ‘William, my boy, my number is up. This is the sack.’ I made certain that Rossiter had run me in for something. He’s been waiting for a chance to do it for weeks, only I’ve been as good as gold and haven’t given it him. I pity you going into the postage. There’s one thing, though. If you can stick it for about a month, you’ll get through all right. Men are always leaving for the East, and then you get shunted on into another department, and the next new man goes into the postage. That’s the best of this place. It’s not like one of those banks where you stay in London all your life. You only have three years here, and then you get your orders, and go to one of the branches in the East, where you’re the dickens of a big pot straight away, with a big screw and a dozen native Johnnies under you. Bit of all right, that. I shan’t get my orders for another two and a half years and more, worse luck. Still, it’s something to look forward to.”

“Who’s Rossiter?” asked Mike.

“The head of the postage department. Fussy little brute. Won’t leave you alone. Always trying to catch you on the hop. There’s one thing, though. The work in the postage is pretty simple. You can’t make many mistakes, if you’re careful. It’s mostly entering letters and stamping them.”

They turned in at the door in the counter, and arrived at a desk which ran parallel to the gangway. There was a high rack running along it, on which were several ledgers. Tall, green-shaded electric lamps gave it rather a cosy look.

As they reached the desk, a little man with short, black whiskers buzzed out from behind a glass screen, where there was another desk.

“Where have you been, Bannister, where have you been? You must not leave your work in this way. There are several letters waiting to be entered. Where have you been?”

“Mr. Bickersdyke sent for me,” said Bannister, with the calm triumph of one who trumps an ace.

“Oh! Ah! Oh! Yes, very well. I see. But get to work, get to work. Who is this?”

“This is a new man. He’s taking my place. I’ve been moved on to the cash.”

“Oh! Ah! Is your name Smith?” asked Mr. Rossiter, turning to Mike.

Mike corrected the rash guess, and gave his name. It struck him as a curious coincidence that he should be asked if his name were Smith, of all others. Not that it is an uncommon name.

“Mr. Bickersdyke told me to expect a Mr. Smith. Well, well, perhaps there are two new men. Mr. Bickersdyke knows we are short-handed in this department. But, come along, Bannister, come along. Show Jackson what he has to do. We must get on. There is no time to waste.”

He buzzed back to his lair. Bannister grinned at Mike. He was a cheerful youth. His normal expression was a grin.

“That’s a sample of Rossiter,” he said. “You’d think from the fuss he’s made that the business of the place was at a standstill till we got to work. Perfect rot! There’s never anything to do here till after lunch, except checking the stamps and petty cash, and I’ve done that ages ago. There are three letters. You may as well enter them. It all looks like work. But you’ll find the best way is to wait till you get a couple of dozen or so, and then work them off in a batch. But if you see Rossiter about, then start stamping something or writing something, or he’ll run you in for neglecting your job. He’s a nut. I’m jolly glad I’m under old Waller now. He’s the pick of the bunch. The other heads of departments are all nuts, and Bickersdyke’s the nuttiest of the lot. Now, look here. This is all you’ve got to do. I’ll just show you, and then you can manage for yourself. I shall have to be shunting off to my own work in a minute.”

CHAPTER V.

the other man.

S Bannister had said,

the work in the postage department was not intricate. There was nothing much to

do except enter and stamp letters, and, at intervals, take them down to the

post office at the end of the street. The nature of the work gave Mike plenty

of time for reflection.

S Bannister had said,

the work in the postage department was not intricate. There was nothing much to

do except enter and stamp letters, and, at intervals, take them down to the

post office at the end of the street. The nature of the work gave Mike plenty

of time for reflection.

His thoughts became gloomy again. All this was very far removed from the life to which he had looked forward. There are some people who take naturally to a life of commerce. Mike was not of these. To him the restraint of the business was irksome. He had been used to an open-air life, and a life, in its way, of excitement. He gathered that he would not be free till five o’clock, and that on the following day he would come at ten and go at five, and the same every day, except Saturdays and Sundays, all the year round, with a ten days’ holiday. The monotony of the prospect appalled him. He was not old enough to know what a narcotic is Habit, and that one can become attached to and interested in the most unpromising jobs. He worked away dismally at his letters till he had finished them. Then there was nothing to do except sit and wait for more.

He looked through the letters he had stamped, and re-read the addresses. Some of them were directed to people living in the country, one to a house which he knew quite well, near to his own home in Shropshire. It made him home-sick, conjuring up visions of shady gardens and country sounds and smells, and the silver Severn gleaming in the distance through the trees. About now, if he were not in this dismal place, he would be lying in the shade in the garden with a book, or wandering down to the river to boat or bathe. That envelope addressed to the man in Shropshire gave him the worst moment he had experienced that day.

The time crept slowly on to one o’clock. At two minutes past Mike awoke from a day-dream to find Mr. Waller standing by his side. The cashier had his hat on.

“I wonder,” said Mr. Waller, “if you would care to come out to lunch. I generally go about this time, and Mr. Rossiter, I know, does not go out till two. I thought perhaps that, being unused to the City, you might have some difficulty in finding your way about.”

“It’s awfully good of you,” said Mike. “I should like to.”

The other led the way through the streets and down obscure alleys till they came to a chop-house. Here one could have the doubtful pleasure of seeing one’s chop in its various stages of evolution. Mr. Waller ordered lunch with the care of one to whom lunch is no slight matter. Few workers in the City do regard lunch as a trivial affair. It is the keynote of their day. It is an oasis in a desert of ink and ledgers. Conversation in city office deals, in the morning, with what one is going to have for lunch, and in the afternoon with what one has had for lunch.

At intervals during the meal Mr. Waller talked. Mike was content to listen. There was something soothing about the grey-bearded one.

“What sort of a man is Bickersdyke?” asked Mike.

“A very able man. A very able man indeed. I’m afraid he’s not popular in the office. A little inclined, perhaps, to be hard on mistakes. I can remember the time when he was quite different. He and I were fellow clerks in Morton and Blatherwick’s. He got on better than I did. A great fellow for getting on. They say he is to be the Unionist candidate for Kenningford when the time comes. A great worker, but perhaps not quite the sort of man to be generally popular in an office.”

“He’s a blighter,” was Mike’s verdict. Mr. Waller made no comment. Mike was to learn later that the manager and the cashier, despite the fact that they had been together in less prosperous days—or possibly because of it—were not on very good terms. Mr. Bickersdyke was a man of strong prejudices, and he disliked the cashier, whom he looked down upon as one who had climbed to a lower rung of the ladder than he himself had reached.

As the hands of the chop-house clock reached a quarter to two, Mr. Waller rose, and led the way back to the office, where they parted for their respective desks. Gratitude for any good turn done to him was a leading characteristic of Mike’s nature; and he felt genuinely grateful to the cashier for troubling to seek him out and be friendly to him.

His three-quarters-of-an-hour absence had led to the accumulation of a small pile of letters on his desk. He sat down and began to work them off. The addresses continued to exercise a fascination for him. He was miles away from the office, speculating on what sort of a man J. B. Garside, Esq., was, and whether he had a good time at his house in Worcestershire, when somebody tapped him on the shoulder.

He looked up.

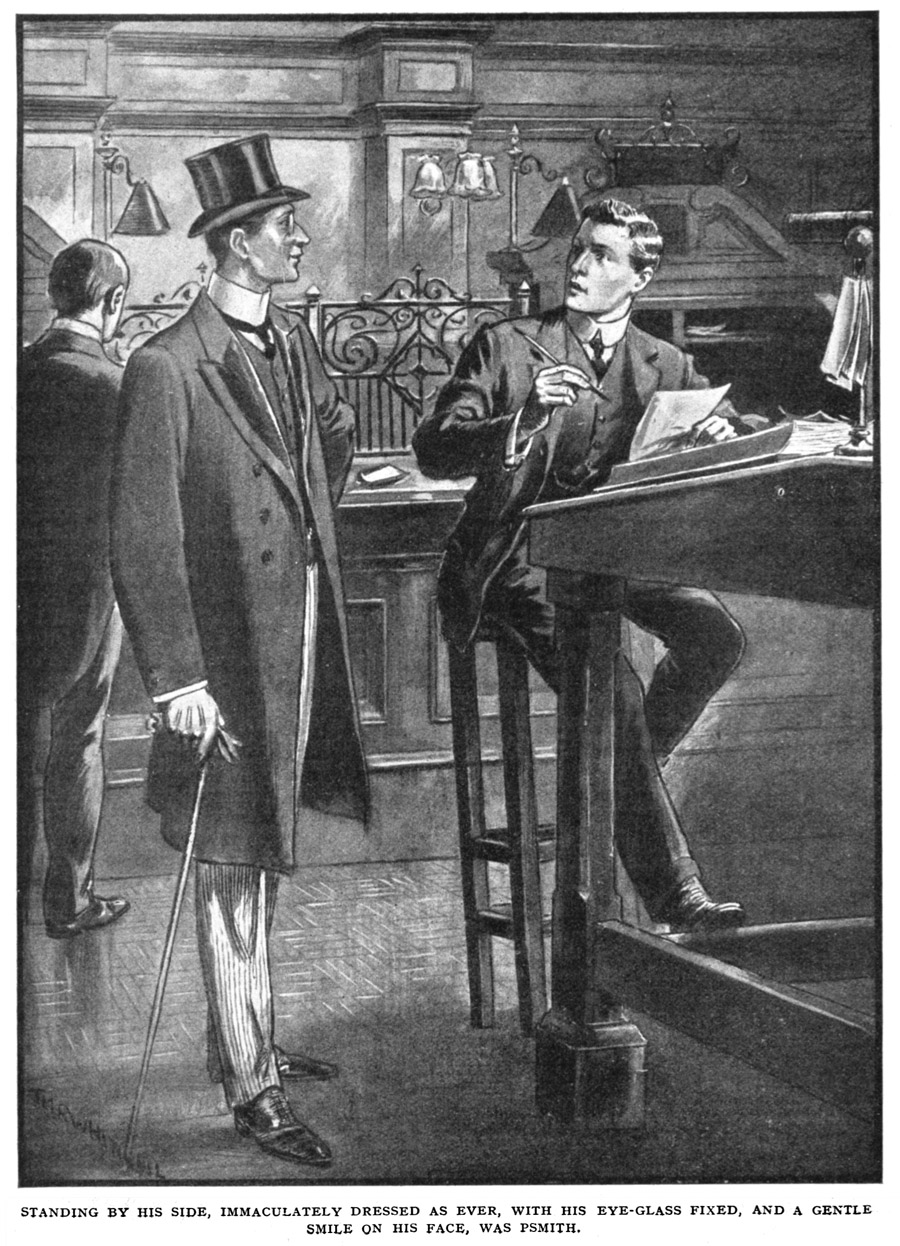

Standing by his side, immaculately dressed as ever, with his eye-glass fixed and a gentle smile on his face, was Psmith.

Mike stared.

“Commerce,” said Psmith, as he drew off his lavender gloves, “has claimed me for her own, Comrade of old. I, too, have joined this blighted institution.”

As he spoke, there was a whirring noise in the immediate neighbourhood, and Mr. Rossiter buzzed out from his den with the esprit and animation of a clock-work toy.

“Who’s here?” said Psmith with interest, removing his eye-glass, polishing it, and replacing it in his eye.

“Mr. Jackson,” exclaimed Mr. Rossiter. “I really must ask you to be good enough to come in from your lunch at the proper time. It was fully seven minutes to two when you returned, and——”

“That little more,” sighed Psmith, “and how much it is!”

“Who are you?” snapped Mr. Rossiter, turning on him.

“I shall be delighted, Comrade——”

“Rossiter,” said Mike, aside.

“Comrade Rossiter. I shall be delighted to furnish you with particulars of my family history. As follows. Soon after the Norman Conquest, a certain Sieur de Psmith grew tired of work—a family failing, alas!—and settled down in this country to live peacefully for the remainder of his life on what he could extract from the local peasantry. He may be described as the founder of the family which ultimately culminated in Me. Passing on——”

Mr. Rossiter refused to pass on.

“What are you doing here? What have you come for?”

“Work,” said Psmith, with simple dignity. “I am now a member of the staff of this bank. Its interests are my interests. Psmith, the individual, ceases to exist, and there springs into being Psmith, the cog in the wheel of the New Asiatic Bank; Psmith, the link in the bank’s chain; Psmith, the Worker. I shall not spare myself,” he proceeded earnestly. “I shall toil with all the accumulated energy of one who, up till now, has only known what work is like from hearsay. Whose is that form sitting on the steps of the bank in the morning, waiting eagerly for the place to open? It is the form of Psmith, the Worker. Whose is that haggard, drawn face which bends over a ledger long after the other toilers have sped blithely westwards to dine at Lyons’ Popular Café? It is the face of Psmith, the Worker.”

“I——” began Mr. Rossiter.

“I tell you,” continued Psmith, waving aside the interruption and tapping the head of the department rhythmically in the region of the second waistcoat-button with a long finger, “I tell you, Comrade Rossiter, that you have got hold of a good man. You and I together, not forgetting Comrade Jackson, the pet of the Smart Set, will toil early and late till we boost up this Postage Department into a shining model of what a Postage Department should be. What that is, at present, I do not exactly know. However. Excursion trains will be run from distant shires to see this Postage Department. American visitors to London will do it before going on to the Tower. And now,” he broke off, with a crisp, businesslike intonation, “I must ask you to excuse me. Much as I have enjoyed this little chat, I fear it must now cease. The time has come to work. Our trade rivals are getting ahead of us. The whisper goes round, ‘Rossiter and Psmith are talking, not working,’ and other firms prepare to pinch our business. Let me Work.”

Two minutes later, Mr. Rossiter was sitting at his desk with a dazed expression, while Psmith, perched gracefully on a stool, entered figures in a ledger.

(To be continued.)

Madame Eulalie’s Rare Plums

Madame Eulalie’s Rare Plums