The Captain, January 1909

CHAPTER XVI.

further developments.

ILL (surname unknown)

was not one of your ultra-scientific fighters. He did not favour the American

crouch and the artistic feint. He had a style wholly his own. It seemed to have

been modelled partly on a tortoise and partly on a windmill. His head he

appeared to be trying to conceal between his shoulders, and he whirled his arms

alternately in circular sweeps.

ILL (surname unknown)

was not one of your ultra-scientific fighters. He did not favour the American

crouch and the artistic feint. He had a style wholly his own. It seemed to have

been modelled partly on a tortoise and partly on a windmill. His head he

appeared to be trying to conceal between his shoulders, and he whirled his arms

alternately in circular sweeps.

Mike, on the other hand, stood upright and hit straight, with the result that he hurt his knuckles very much on his opponent’s skull, without seeming to disturb the latter to any great extent. In the process he received one of the windmill swings on the left ear. The crowd, strong pro-Billites, raised a cheer.

This maddened Mike. He assumed the offensive. Bill, satisfied for the moment with his success, had stepped back, and was indulging in some fancy sparring, when Mike sprang upon him like a panther. They clinched, and Mike, who had got the under grip, hurled Bill forcibly against a stout man who looked like a publican. The two fell in a heap, Bill underneath.

At the same time Bill’s friends joined in.

The first intimation Mike had of this was a violent blow across the shoulders with a walking-stick. Even if he had been wearing his overcoat, the blow would have hurt. As he was in his jacket it hurt more than anything he had ever experienced in his life. He leapt up with a yell, but Psmith was there before him. Mike saw his assailant lift the stick again, and then collapse as the old Etonian’s right took him under the chin.

He darted to Psmith’s side.

“This is no place for us,” observed the latter sadly. “Shift ho, I think. Come on.”

They dashed simultaneously for the spot where the crowd was thinnest. The ring which had formed round Mike and Bill had broken up as the result of the intervention of Bill’s allies, and at the spot for which they ran only two men were standing. And these had apparently made up their minds that neutrality was the best policy, for they made no movement to stop them. Psmith and Mike charged through the gap, and raced for the road.

The suddenness of the move gave them just the start they needed. Mike looked over his shoulder. The crowd, to a man, seemed to be following. Bill, excavated from beneath the publican, led the field. Lying a good second came a band of three, and after them the rest in a bunch.

They reached the road in this order.

Some fifty yards down the road was a stationary tram. In the ordinary course of things it would probably have moved on long before Psmith and Mike could have got to it; but the conductor, a man with sporting blood in him, seeing what appeared to be the finish of some Marathon Race, refrained from giving the signal, and moved out into the road to observe events more clearly, at the same time calling to the driver, who joined him. Passengers on the roof stood up to get a good view. There was some cheering.

Psmith and Mike reached the tram ten yards to the good; and, if it had been ready to start then, all would have been well. But Bill and his friends had arrived while the driver and conductor were both out in the road.

The affair now began to resemble the doings of Horatius on the bridge. Psmith and Mike turned to bay on the platform at the foot of the tram steps. Bill, leading by three yards, sprang on to it, grabbed Mike, and fell with him on to the road. Psmith, descending with a dignity somewhat lessened by the fact that his hat was on the side of his head, was in time to engage the runners-up.

Psmith, as pugilist, lacked something of the calm majesty which characterized him in the more peaceful moments of life, but he was undoubtedly effective. Nature had given him an enormous reach and a lightness on his feet remarkable in one of his size; and at some time in his career he appeared to have learned how to use his hands. The first of the three runners, the walking-stick manipulator, had the misfortune to charge straight into the old Etonian’s left. It was a well-timed blow, and the force of it, added to the speed at which the victim was running, sent him on to the pavement, where he spun round and sat down. In the subsequent proceedings he took no part.

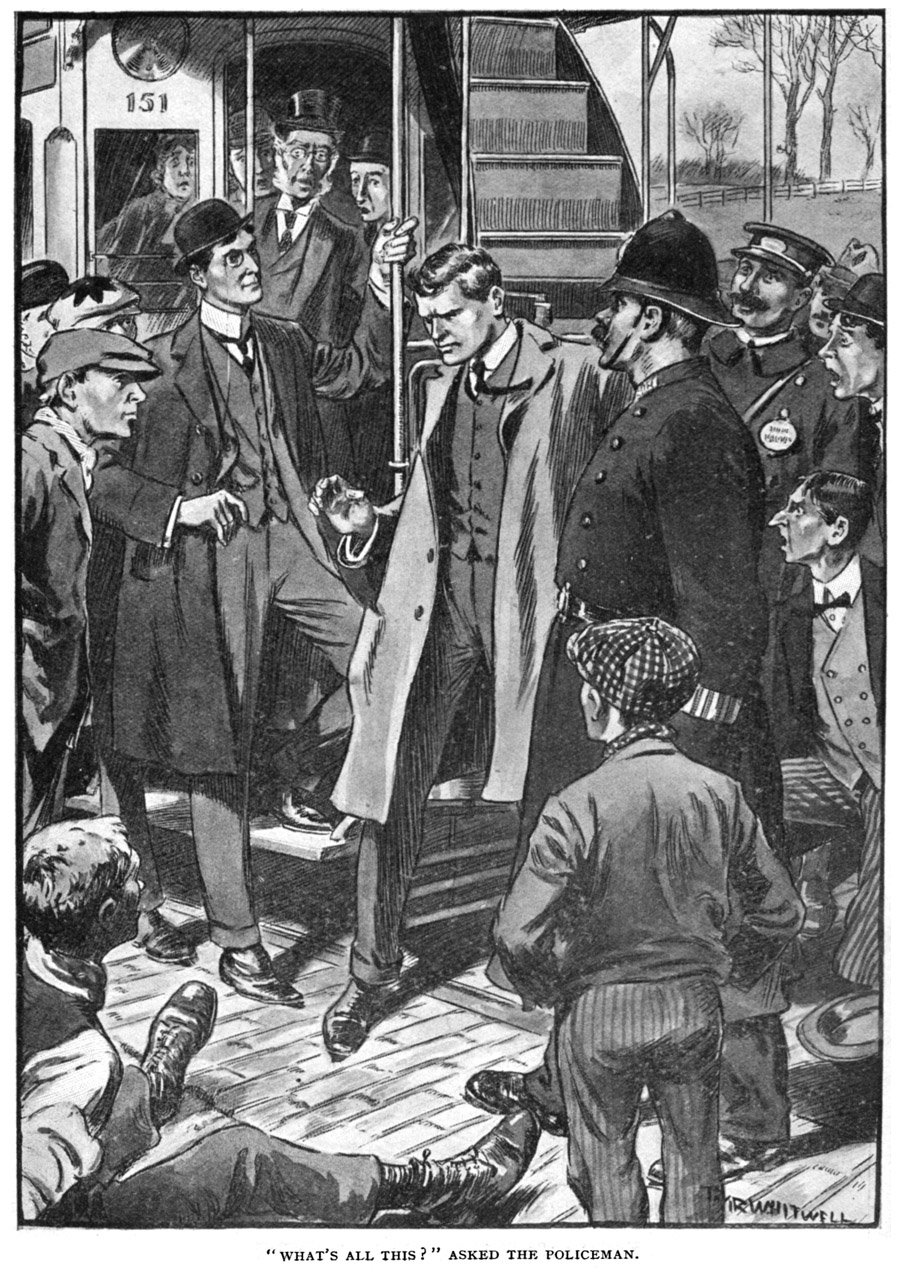

The other two attacked Psmith simultaneously, one on each side. In doing so, the one on the left tripped over Mike and Bill, who were still in the process of sorting themselves out, and fell, leaving Psmith free to attend to the other. He was a tall, weedy youth. His conspicuous features were a long nose and a light yellow waistcoat. Psmith hit him on the former with his left and on the latter with his right. The long youth emitted a gurgle, and collided with Bill, who had wrenched himself free from Mike and staggered to his feet. Bill, having received a second blow in the eye during the course of his interview on the road with Mike, was not feeling himself. Mistaking the other for an enemy, he proceeded to smite him in the parts about the jaw. He had just upset him, when a stern official voice observed, “ ’Ere, now, what’s all this?”

There is no more unfailing corrective to a scene of strife than the “What’s all this?” of the London policeman. Bill abandoned his intention of stamping on the prostrate one, and the latter, sitting up, blinked and was silent.

“What’s all this?” asked the policeman again. Psmith, adjusting his hat at the correct angle again, undertook the explanations.

“A distressing scene, officer,” he said. “A case of that unbridled brawling which is, alas, but too common in our London streets. These two, possibly till now the closest friends, fall out over some point, probably of the most trivial nature, and what happens? They brawl. They——”

“He ’it me,” said the long youth, dabbing at his face with a handkerchief and pointing an accusing finger at Psmith, who regarded him through his eyeglass with a look in which pity and censure were nicely blended.

Bill, meanwhile, circling round restlessly, in the apparent hope of getting past the Law and having another encounter with Mike, expressed himself in a stream of language which drew stern reproof from the shocked constable. “You ’op it,” concluded the man in blue. “That’s what you do. You ’op it.”

“I should,” said Psmith kindly. “The officer is speaking in your best interests. A man of taste and discernment, he knows what is best. His advice is good, and should be followed.”

The constable seemed to notice Psmith for the first time. He turned and stared at him. Psmith’s praise had not had the effect of softening him. His look was one of suspicion.

“And what might you have been up to?” he inquired coldly. “This man says you hit him.”

Psmith waved the matter aside.

“Purely in self-defence,” he said, “purely in self-defence. What else could the man of spirit do? A mere tap to discourage an aggressive movement.”

The policeman stood silent, weighing matters in the balance. He produced a notebook and sucked his pencil. Then he called the conductor of the tram as a witness.

“A brainy and admirable step,” said Psmith, approvingly. “This rugged, honest man, all unused to verbal subtleties, shall give us his plain account of what happened. After which, as I presume this tram—little as I know of the habits of trams—has got to go somewhere to-day, I would suggest that we all separated and moved on.”

He took two half-crowns from his pocket, and began to clink them meditatively together. A slight softening of the frigidity of the constable’s manner became noticeable. There was a milder beam in the eyes which gazed into Psmith’s.

Nor did the conductor seem altogether uninfluenced by the sight.

The conductor deposed that he had bin on the point of pushing on, seeing as how he’d hung abart long enough, when he see’d them two gents, the long ’un with the heye-glass (Psmith bowed) and t’other ’un, a-legging of it dahn the road towards him, with the other blokes pelting after ’em. He added that, when they reached the trem, the two gents had got aboard, and was then set upon by the blokes. And after that, he concluded, well, there was a bit of a scrap, and that’s how it was.

“Lucidly and excellently put,” said Psmith. “That is just how it was. Comrade Jackson, I fancy we leave the court without a stain on our characters. We win through. Er—constable, we have given you a great deal of trouble. Possibly——?”

“Thank you, sir.” There was a musical clinking. “Now then, all of you, you ’op it. You’ve all bin poking your noses in ’ere long enough. Pop off. Get on with that tram, conductor.”

Psmith and Mike settled themselves in a seat on the roof. When the conductor came along, Psmith gave him half a crown, and asked after his wife and the little ones at home. The conductor thanked goodness that he was a bachelor, punched the tickets, and retired.

“Subject for a historical picture,” said Psmith. “Wounded leaving the field after the Battle of Clapham Common. How are your injuries, Comrade Jackson?”

“My back’s hurting like blazes,” said Mike. “And my ear’s all sore where that chap got me. Anything the matter with you?”

“Physically,” said Psmith, “no. Spiritually much. Do you realize, Comrade Jackson, the thing that has happened? I am riding in a tram. I, Psmith, have paid a penny for a ticket on a tram. If this should get about the clubs! I tell you, Comrade Jackson, no such crisis has ever occurred before in the course of my career.”

“You can always get off, you know,” said Mike.

“He thinks of everything,” said Psmith, admiringly. “You have touched the spot with an unerring finger. Let us descend. I observe in the distance a cab. That looks to me more the sort of thing we want. Let us go and parley with the driver.”

CHAPTER XVII.

sunday supper.

HE cab took them back

to the flat, at considerable expense, and Psmith requested Mike to make tea, a

performance in which he himself was interested purely as a spectator. He had

views on the subject of tea-making which he liked to expound from an arm-chair

or sofa, but he never got further than this. Mike, his back throbbing dully

from the blow he had received, and feeling more than a little sore all over,

prepared the Etna, fetched the milk, and finally produced the finished article.

HE cab took them back

to the flat, at considerable expense, and Psmith requested Mike to make tea, a

performance in which he himself was interested purely as a spectator. He had

views on the subject of tea-making which he liked to expound from an arm-chair

or sofa, but he never got further than this. Mike, his back throbbing dully

from the blow he had received, and feeling more than a little sore all over,

prepared the Etna, fetched the milk, and finally produced the finished article.

Psmith sipped meditatively.

“How pleasant,” he said, “after strife is rest. We shouldn’t have appreciated this simple cup of tea had our sensibilities remained unstirred this afternoon. We can now sit at our ease, like warriors after the fray, till the time comes for setting out to Comrade Waller’s once more.”

Mike looked up.

“What! You don’t mean to say you’re going to sweat out to Clapham again?”

“Undoubtedly. Comrade Waller is expecting us to supper.”

“What absolute rot! We can’t fag back there.”

“Noblesse oblige. The cry has gone round the Waller household, ‘Jackson and Psmith are coming to supper,’ and we cannot disappoint them now. Already the fatted blanc-mange has been killed, and the table creaks beneath what’s left of the mid-day beef. We must be there. Besides, don’t you want to see how the poor man is? Probably we shall find him in the act of emitting his last breath. I expect he was lynched by the enthusiastic mob.”

“Not much,” grinned Mike. “They were too busy with us. All right, I’ll come if you really want me to, but it’s awful rot.”

One of the many things Mike could never understand in Psmith was his fondness for getting into atmospheres that were not his own. He would go out of his way to do this. Mike, like most boys of his age, was never really happy and at his ease except in the presence of those of his own years and class. Psmith, on the contrary, seemed to be bored by them, and infinitely preferred talking to somebody who lived in quite another world. Mike was not a snob. He simply had not the ability to be at his ease with people in another class from his own. He did not know what to talk to them about, unless they were cricket professionals. With them he was never at a loss.

But Psmith was different. He could get on with anyone. He seemed to have the gift of entering into their minds and seeing things from their point of view.

As regarded Mr. Waller, Mike liked him personally, and was prepared, as we have seen, to undertake considerable risks in his defence; but he loathed with all his heart and soul the idea of supper at his house. He knew that he would have nothing to say. Whereas Psmith gave him the impression of looking forward to the thing as a treat.

The house where Mr. Waller lived was one of a row of semi-detached villas on the north side of the Common. The door was opened to them by their host himself. So far from looking battered and emitting last breaths, he appeared particularly spruce. He had just returned from Church, and was still wearing his gloves and tall hat. He squeaked with surprise when he saw who were standing on the mat.

“Why, dear me, dear me,” he said. “Here you are! I have been wondering what had happened to you. I was afraid that you might have been seriously hurt. I was afraid those ruffians might have injured you. When last I saw you, you were being——”

“Chivvied,” interposed Psmith, with dignified melancholy. “Do not let us try to wrap the fact up in pleasant words. We were being chivvied. We were legging it with the infuriated mob at our heels. An ignominious position for a Shropshire Psmith, but, after all, Napoleon did the same.”

“But what happened? I could not see. I only know that quite suddenly the people seemed to stop listening to me, and all gathered round you and Jackson. And then I saw that Jackson was engaged in a fight with a young man.”

“Comrade Jackson, I imagine, having heard a great deal about all men being equal, was anxious to test the theory, and see whether Comrade Bill was as good a man as he was. The experiment was broken off prematurely, but I personally should be inclined to say that Comrade Jackson had a shade the better of the exchanges.”

Mr. Waller looked with interest at Mike, who shuffled and felt awkward. He was hoping that Psmith would say nothing about the reason of his engaging Bill in combat. He had an uneasy feeling that Mr. Waller’s gratitude would be effusive and overpowering, and he did not wish to pose as the brave young hero. There are moments when one does not feel equal to the rôle.

Fortunately, before Mr. Waller had time to ask any further questions, the supper-bell sounded, and they went into the dining-room.

Sunday supper, unless done on a large and informal scale, is probably the most depressing meal on record. There is a chill discomfort in the round of beef, an icy severity about the open jam tart. The blanc-mange shivers miserably.

Spirituous liquor helps to counteract the influence of these things, and so does exhilarating conversation. Unfortunately, at Mr. Waller’s table there was neither. The cashier’s views on temperance were not merely for the platform; they extended to the home. And the company was not of the exhilarating sort. Besides Psmith and Mike and their host, there were four people present—Comrade Prebble, the orator; a young man of the name of Richards; Mr. Waller’s niece, answering to the name of Ada, who was engaged to Mr. Richards; and Edward.

Edward was Mr. Waller’s son. He was ten years old, wore a very tight Eton suit, and had the peculiarly loathsome expression which a snub nose sometimes gives to the young.

It would have been plain to the most casual observer that Mr. Waller was fond and proud of his son. The cashier was a widower, and after five minutes’ acquaintance with Edward, Mike felt strongly that Mrs. Waller was the lucky one. Edward sat next to Mike, and showed a tendency to concentrate his conversation on him. Psmith, at the opposite end of the table, beamed in a fatherly manner upon the pair through his eye-glass.

Mike got on with small girls reasonably well. He preferred them at a distance, but, if cornered by them, could put up a fairly good show. Small boys, however, filled him with a sort of frozen horror. It was his view that a boy should not be exhibited publicly until he reached an age when he might be in the running for some sort of colours at a public school.

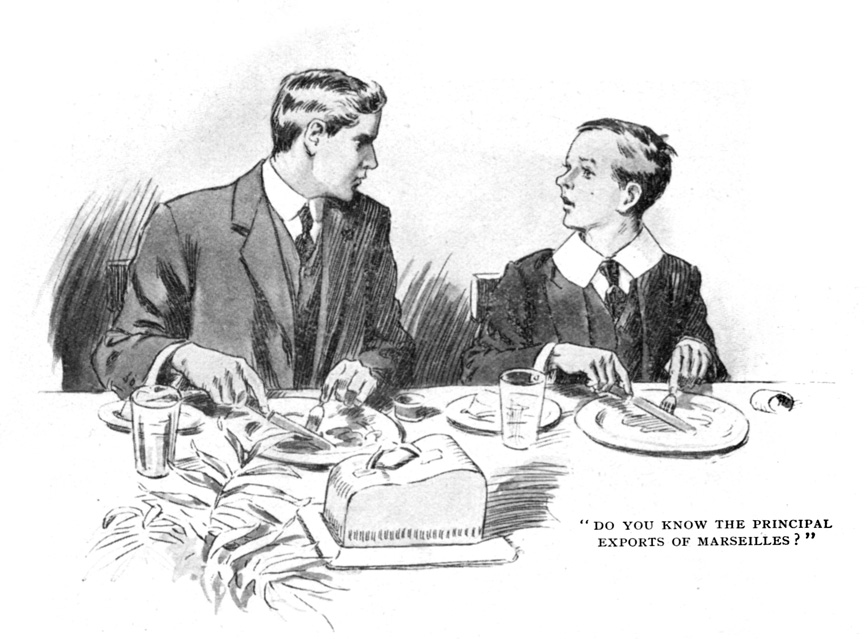

Edward was one of those well-informed small boys. He opened on Mike with the first mouthful.

“Do you know the principal exports of Marseilles?” he inquired.

“What?” said Mike coldly.

“Do you know the principal exports of Marseilles? I do.”

“Oh?” said Mike.

“Yes. Do you know the capital of Madagascar?”

Mike, as crimson as the beef he was attacking, said he did not.

“I do.”

“Oh?” said Mike.

“Who was the first king——?”

“You mustn’t worry Mr. Jackson, Teddy,” said Mr. Waller, with a touch of pride in his voice, as who should say, “There are not many boys of his age, I can tell you, who could worry you with questions like that.”

“No, no, he likes it,” said Psmith, unnecessarily. “He likes it. I always hold that much may be learned by casual chit-chat across the dinner-table. I owe much of my own grasp of——”

“I bet you don’t know what’s the capital of Madagascar,” interrupted Mike rudely.

“I do,” said Edward. “I can tell you the kings of Israel, if you like. Do you know the kings of Israel?” he added, turning to Mike. He seemed to have no curiosity as to the extent of Psmith’s knowledge. Mike’s appeared to fascinate him.

Mike helped himself to beetroot in moody silence.

His mouth was full when Comrade Prebble asked him a question. Comrade Prebble, as has been pointed out in an earlier part of the narrative, was a good chap, but had no roof to his mouth.

“I beg your pardon?” said Mike.

Comrade Prebble repeated his observation. Mike looked helplessly at Psmith, but Psmith’s eyes were on his plate.

Mike felt he must venture on some answer.

“No,” he said decidedly.

Comrade Prebble seemed slightly taken aback. There was an awkward pause. Then Mr. Waller, for whom his fellow Socialist’s methods of conversation held no mysteries, interpreted.

“The mustard, Prebble? Yes, yes. Would you mind passing Prebble the mustard, Mr. Jackson?”

“Oh, sorry,” gasped Mike, and, reaching out, upset the water-jug into the open jam-tart.

Through the black mist which rose before his eyes as he leaped to his feet and stammered apologies came the dispassionate voice of Master Edward Waller reminding him that mustard was first introduced into Peru by Cortez.

His host was all courtesy and consideration. He passed the matter off genially. But life can never be quite the same after you have upset a water-jug into an open jam-tart at the table of a comparative stranger. Mike’s nerve had gone. He ate on, but he was a broken man.

At the other end of the table it became gradually apparent that things were not going on altogether as they should have done. There was a sort of bleakness in the atmosphere. Young Mr. Richards was looking like a stuffed fish, and the face of Ada, Mr. Waller’s niece, was cold and set.

“Why, come, come, Ada,” said Mr. Waller, breezily, “what’s the matter? You’re eating nothing. What’s George been saying to you?” he added jocularly.

“Thank you, uncle Robert,” replied Ada precisely, “there’s nothing the matter. Nothing that Mr. Richards can say to me can upset me.”

“Mr. Richards!” echoed Mr. Waller in astonishment. How was he to know that, during the walk back from church, the world had been transformed, George had become Mr. Richards, and all was over?

“I assure you, Ada——” began that unfortunate young man. Ada turned a frigid shoulder towards him.

“Come, come,” said Mr. Waller, disturbed. “What’s all this? What’s all this?”

His niece burst into tears and left the room.

If there is anything more embarrassing to a guest than a family row, we have yet to hear of it. Mike, scarlet to the extreme edges of his ears, concentrated himself on his plate. Comrade Prebble made a great many remarks, which were probably illuminating, if they could have been understood. Mr. Waller looked, astonished, at Mr. Richards. Mr. Richards, pink but dogged, loosened his collar, but said nothing. Psmith, leaning forward, asked Master Edward Waller his opinion on the Licensing Bill.

“We happened to have a word or two,” said Mr. Richards at length, “on the way home from church on the subject of Women’s Suffrage.”

“That fatal topic!” murmured Psmith.

“In Australia——” began Master Edward Waller.

“I was rayther—well, rayther facetious about it,” continued Mr. Richards.

Psmith clicked his tongue sympathetically.

“In Australia——” said Edward.

“I went talking on, laughing and joking, when all of a sudden she flew out at me. How was I to know she was ’eart and soul in the movement? You never told me,” he added accusingly to his host.

“In Australia——” said Edward.

“I’ll go and try and get her round. How was I to know?”

Mr. Richards thrust back his chair and bounded from the room.

“Now, iawinyaw, iear oiler——” said Comrade Prebble judicially, but was interrupted.

“How very disturbing!” said Mr. Waller. “I am so sorry that this should have happened. Ada is such a touchy, sensitive girl. She——”

“In Australia,” said Edward in even tones, “they’ve got Women’s Suffrage already. Did you know that?” he said to Mike.

Mike made no answer. His eyes were fixed on his plate. A bead of perspiration began to roll down his forehead. If his feelings could have been ascertained at that moment, they would have been summed up in the words, “Death, where is thy sting?”

CHAPTER XVIII.

psmith makes a discovery.

OMEN,” said Psmith,

helping himself to trifle, and speaking with the air of one launched upon his

special subject, “are, one must recollect, like—like—er, well, in fact, just

so. Passing on lightly from that conclusion, let us turn for a moment to the

Rights of Property, in connection with which Comrade Prebble and yourself had

so much that was interesting to say this afternoon. Perhaps you”—he bowed in

Comrade Prebble’s direction—“would resume, for the benefit of Comrade Jackson—a

novice in the Cause, but earnest—your very lucid——”

OMEN,” said Psmith,

helping himself to trifle, and speaking with the air of one launched upon his

special subject, “are, one must recollect, like—like—er, well, in fact, just

so. Passing on lightly from that conclusion, let us turn for a moment to the

Rights of Property, in connection with which Comrade Prebble and yourself had

so much that was interesting to say this afternoon. Perhaps you”—he bowed in

Comrade Prebble’s direction—“would resume, for the benefit of Comrade Jackson—a

novice in the Cause, but earnest—your very lucid——”

Comrade Prebble beamed, and took the floor. Mike began to realize that, till now, he had never known what boredom meant. There had been moments in his life which had been less interesting than other moments, but nothing to touch this for agony. Comrade Prebble’s address streamed on like water rushing over a weir. Every now and then there was a word or two which was recognisable, but this happened so rarely that it amounted to little. Sometimes Mr. Waller would interject a remark, but not often. He seemed to be of opinion that Comrade Prebble’s was the master mind, and that to add anything to his views would be in the nature of painting the lily and gilding the refined gold. Mike himself said nothing. Psmith and Edward were equally silent. The former sat like one in a trance, thinking his own thoughts, while Edward, who, prospecting on the sideboard, had located a rich biscuit-mine, was too occupied for speech.

After about twenty minutes, during which Mike’s discomfort changed to a dull resignation, Mr. Waller suggested a move to the drawing-room, where Ada, he said, would play some hymns.

The prospect did not dazzle Mike, but any change, he thought, must be for the better. He had sat staring at the ruin of the blanc-mange so long that it had begun to hypnotize him. Also, the move had the excellent result of eliminating the snub-nosed Edward, who was sent to bed. His last words were in the form of a question, addressed to Mike, on the subject of the hypotenuse and the square upon the same.

“A remarkably intelligent boy,” said Psmith. “You must let him come to tea at our flat one day. I may not be in myself—I have many duties which keep me away—but Comrade Jackson is sure to be there, and will be delighted to chat with him.”

On the way upstairs Mike tried to get Psmith to himself for a moment, to suggest the advisability of an early departure; but Psmith was in close conversation with his host. Mike was left to Comrade Prebble, who, apparently, had only touched the fringe of his subject in his lecture in the dining-room.

When Mr. Waller had predicted hymns in the drawing-room, he had been too sanguine (or too pessimistic). Of Ada, when they arrived, there were no signs. It seemed that she had gone straight to bed. Young Mr. Richards was sitting on the sofa, moodily turning the leaves of a photograph album, which contained portraits of Master Edward Waller in geometrically progressing degrees of repulsiveness—here, in frocks, looking like a gargoyle; there, in sailor suit, looking like nothing on earth. The inspection of these was obviously deepening Mr. Richards’ gloom, but he proceeded doggedly with it.

Comrade Prebble backed the reluctant Mike into a corner, and, like the Ancient Mariner, held him with a glittering eye. Psmith and Mr. Waller, in the opposite corner, were looking at something with their heads close together. Mike definitely abandoned all hope of a rescue from Psmith, and tried to buoy himself up with the reflection that this could not last for ever.

Hours seemed to pass, and then at last he heard Psmith’s voice saying good-bye to his host.

He sprang to his feet. Comrade Prebble was in the middle of a sentence, but this was no time for polished courtesy. He felt that he must get away, and at once. “I fear,” Psmith was saying, “that we must tear ourselves away. We have greatly enjoyed our evening. You must look us up at our flat one day, and bring Comrade Prebble. If I am not in, Comrade Jackson is certain to be, and he will be more than delighted to hear Comrade Prebble speak further on the subject of which he is such a master.” Comrade Prebble was understood to say that he would certainly come. Mr. Waller beamed. Mr. Richards, still steeped in gloom, shook hands in silence.

Out in the road, with the front door shut behind them, Mike spoke his mind.

“Look here, Smith,” he said definitely, “if being your confidential secretary and adviser is going to let me in for any more of that sort of thing, you can jolly well accept my resignation.”

“The orgy was not to your taste?” said Psmith sympathetically.

Mike laughed. One of those short, hollow, bitter laughs.

“I am at a loss, Comrade Jackson,” said Psmith, “to understand your attitude. You fed sumptuously. You had fun with the crockery—that knockabout act of yours with the water-jug was alone worth the money—and you had the advantage of listening to the views of a master of his subject. What more do you want?”

“What on earth did you land me with that man Prebble for?”

“Land you! Why, you courted his society. I had practically to drag you away from him. When I got up to say good-bye, you were listening to him with bulging eyes. I never saw such a picture of rapt attention. Do you mean to tell me, Comrade Jackson, that your appearance belied you, that you were not interested? Well, well. How we misread our fellow creatures.”

“I think you might have come and lent a hand with Prebble. It was a bit thick.”

“I was too absorbed with Comrade Waller. We were talking of things of vital moment. However, the night is yet young. We will take this cab, wend our way to the West, seek a café, and cheer ourselves with light refreshments.”

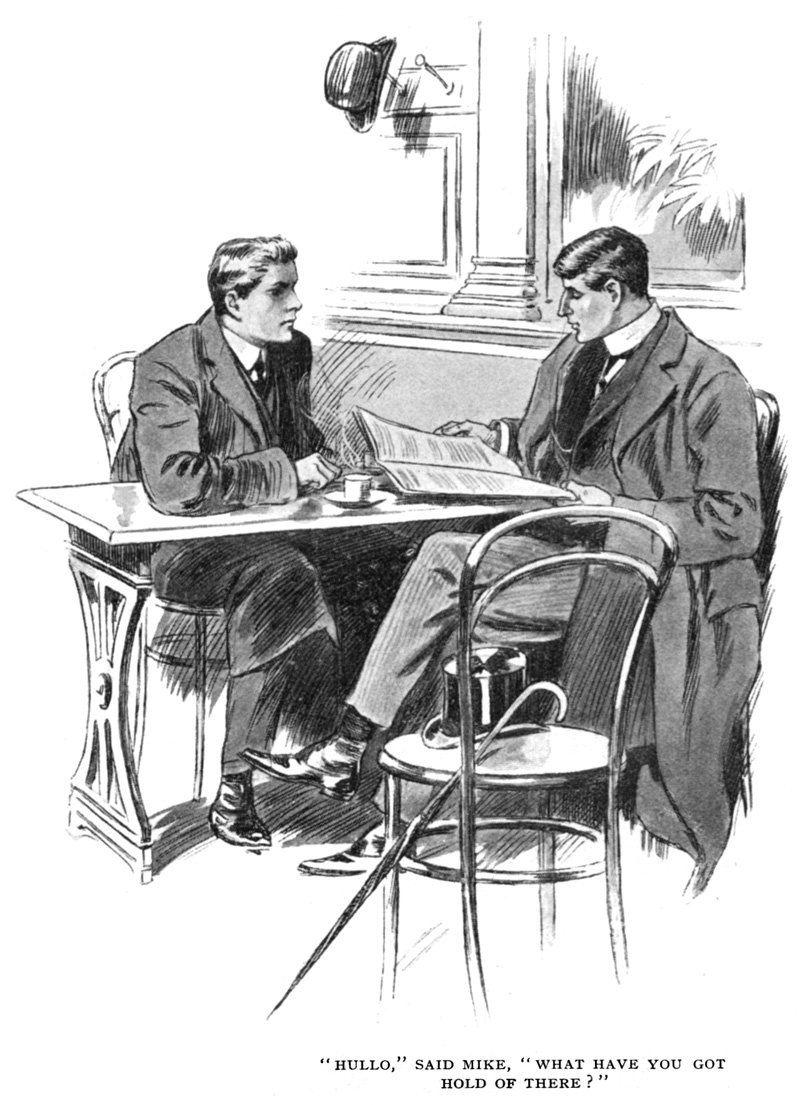

Arrived at a café whose window appeared to be a sort of museum of every kind of German sausage, they took possession of a vacant table and ordered coffee. Mike soon found himself soothed by his bright surroundings, and gradually his impressions of blanc-mange, Edward, and Comrade Prebble faded from his mind. Psmith, meanwhile, was preserving an unusual silence, being deep in a large square book of the sort in which press-cuttings are pasted. As Psmith scanned its contents a curious smile lit up his face. His reflections seemed to be of an agreeable nature.

“Hullo,” said Mike, “what have you got hold of there? Where did you get that?”

“Comrade Waller very kindly lent it to me. He showed it to me after supper, knowing how enthusiastically I was attached to the Cause. Had you been less tensely wrapped up in Comrade Prebble’s conversation, I would have desired you to step across and join us. However, you now have your opportunity.”

“But what is it?” asked Mike.

“It is the record of the meetings of the Tulse Hill Parliament,” said Psmith impressively. “A faithful record of all they said, all the votes of confidence they passed in the Government, and also all the nasty knocks they gave it from time to time.”

“What on earth’s the Tulse Hill Parliament?”

“It is, alas,” said Psmith in a grave, sad voice, “no more. In life it was beautiful, but now it has done the Tom Bowling act. It has gone aloft. We are dealing, Comrade Jackson, not with the live, vivid present, but with the far-off, rusty past. And yet, in a way, there is a touch of the live, vivid present mixed up in it.”

“I don’t know what the dickens you’re talking about,” said Mike. “Let’s have a look, anyway.”

Psmith handed him the volume, and, leaning back, sipped his coffee, and watched him. At first Mike’s face was bored and blank, but suddenly an interested look came into it.

“Aha!” said Psmith.

“Who’s Bickersdyke? Anything to do with our Bickersdyke?”

“No other than our genial friend himself.”

Mike turned the pages, reading a line or two on each.

“Hullo!” he said, chuckling. “He lets himself go a bit, doesn’t he!”

“He does,” acknowledged Psmith. “A fiery, passionate nature, that of Comrade Bickersdyke.”

“He’s simply cursing the Government here. Giving them frightful beans.”

Psmith nodded.

“I noticed the fact myself.”

“But what’s it all about?”

“As far as I can glean from Comrade Waller,” said Psmith, “about twenty years ago, when he and Comrade Bickersdyke worked hand-in-hand as fellow clerks at the New Asiatic, they were both members of the Tulse Hill Parliament, that powerful institution. At that time Comrade Bickersdyke was as fruity a Socialist as Comrade Waller is now. Only, apparently, as he began to get on a bit in the world, he altered his views to some extent as regards the iniquity of freezing on to a decent share of the doubloons. And that, you see, is where the dim and rusty past begins to get mixed up with the live, vivid present. If any tactless person were to publish those very able speeches made by Comrade Bickersdyke when a bulwark of the Tulse Hill Parliament, our revered chief would be more or less caught bending, if I may employ the expression, as regards his chances of getting in as Unionist candidate at Kenningford. You follow me, Watson? I rather fancy the light-hearted electors of Kenningford, from what I have seen of their rather acute sense of humour, would be, as it were, all over it. It would be very, very trying for Comrade Bickersdyke if these speeches of his were to get about.”

“You aren’t going to——!”

“I shall do nothing rashly. I shall merely place this handsome volume among my treasured books. I shall add it to my ‘Books that have Helped Me’ series. Because I fancy that, in an emergency, it may not be at all a bad thing to have about me. And now,” he concluded, “as the hour is getting late, perhaps we had better be shoving off for home.”

CHAPTER XIX.

the illness of edward.

IFE in a bank is at

its pleasantest in the winter. When all the world outside is dark and damp and

cold, the light and warmth of the place are comforting. There is a pleasant air

of solidity about the interior of a bank. The green shaded lamps look cosy.

And, the outside world offering so few attractions, the worker, perched on his

stool, feels that he is not so badly off after all. It is when the days are

long and the sun beats hot on the pavement, and everything shouts to him how

splendid it is out in the country, that he begins to grow restless.

IFE in a bank is at

its pleasantest in the winter. When all the world outside is dark and damp and

cold, the light and warmth of the place are comforting. There is a pleasant air

of solidity about the interior of a bank. The green shaded lamps look cosy.

And, the outside world offering so few attractions, the worker, perched on his

stool, feels that he is not so badly off after all. It is when the days are

long and the sun beats hot on the pavement, and everything shouts to him how

splendid it is out in the country, that he begins to grow restless.

Mike, except for a fortnight at the beginning of his career in the New Asiatic Bank, had not had to stand the test of sunshine. At present, the weather being cold and dismal, he was almost entirely contented. Now that he had got into the swing of his work, the days passed very quickly; and with his life after office-hours he had no fault to find at all.

His life was very regular. He would arrive in the morning just in time to sign his name in the attendance-book before it was removed to the accountant’s room. That was at ten o’clock. From ten to eleven he would potter. There was nothing going on at that time in his department, and Mr. Waller seemed to take it for granted that he should stroll off to the Postage Department and talk to Psmith, who had generally some fresh grievance against the ring-wearing Bristow to air. From eleven to half-past twelve he would put in a little gentle work. Lunch, unless there was a rush of business or Mr. Waller happened to suffer from a spasm of conscientiousness, could be spun out from half-past twelve to two. More work from two till half-past three. From half-past three till half-past four tea in the tearoom, with a novel. And from half-past four till five either a little more work or more pottering, according to whether there was any work to do or not. It was by no means an unpleasant mode of spending a late January day.

Then there was no doubt that it was an interesting little community, that of the New Asiatic Bank. The curiously amateurish nature of the institution lent a certain air of light-heartedness to the place. It was not like one of those banks whose London office is their main office, where stern business is everything and a man becomes a mere machine for getting through a certain amount of routine work. The employees of the New Asiatic Bank, having plenty of time on their hands, were able to retain their individuality. They had leisure to think of other things besides their work. Indeed, they had so much leisure that it is a wonder they thought of their work at all.

The place was full of quaint characters. There was West, who had been requested to leave Haileybury owing to his habit of borrowing horses and attending meets in the neighbourhood, the same being always out of bounds and necessitating a complete disregard of the rules respecting evening chapel and lock-up. He was a small, dried-up youth, with black hair plastered down on his head. He went about his duties in a costume which suggested the sportsman of the comic papers.

There was also Hignett, who added to the meagre salary allowed him by the bank by singing comic songs at the minor music halls. He confided to Mike his intention of leaving the bank as soon as he had made a name, and taking seriously to the business. He told him that he had knocked them at the Bedford the week before, and in support of the statement showed him a cutting from the Era, in which the writer said that “Other acceptable turns were the Bounding Zouaves, Steingruber’s Dogs, and Arthur Hignett.” Mike wished him luck.

And there was Raymond who dabbled in journalism and was the author of “Straight Talks to Housewives” in Trifles, under the pseudonym of “Lady Gussie”; Wragge, who believed that the earth was flat, and addressed meetings on the subject in Hyde Park on Sundays; and many others, all interesting to talk to of a morning when work was slack and time had to be filled in.

Mike found himself, by degrees, growing quite attached to the New Asiatic Bank.

One morning, early in February, he noticed a curious change in Mr. Waller. The head of the Cash Department was, as a rule, mildly cheerful on arrival, and apt (excessively, Mike thought, though he always listened with polite interest) to relate the most recent sayings and doings of his snub-nosed son, Edward. No action of this young prodigy was withheld from Mike. He had heard, on different occasions, how he had won a prize at his school for General Information (which Mike could well believe); how he had trapped young Mr. Richards, now happily reconciled to Ada, with an ingenious verbal catch; and how he had made a sequence of diverting puns on the name of the new curate, during the course of that cleric’s first Sunday afternoon visit.

On this particular day, however, the cashier was silent and absent-minded. He answered Mike’s good-morning mechanically, and sitting down at his desk, stared blankly across the building. There was a curiously grey, tired look on his face.

Mike could not make it out. He did not like to ask if there was anything the matter. Mr. Waller’s face had the unreasonable effect on him of making him feel shy and awkward. Anything in the nature of sorrow always dried Mike up and robbed him of the power of speech. Being naturally sympathetic, he had raged inwardly in many a crisis at this devil of dumb awkwardness which possessed him and prevented him from putting his sympathy into words. He had always envied the cooing readiness of the hero on the stage when any one was in trouble. He wondered whether he would ever acquire that knack of pouring out a limpid stream of soothing words on such occasions. At present he could get no farther than a scowl and an almost offensive gruffness.

The happy thought struck him of consulting Psmith. It was his hour for pottering, so he pottered round to the Postage Department, where he found the old Etonian eyeing with disfavour a new satin tie which Bristow was wearing that morning for the first time.

“I say, Smith,” he said, “I want to speak to you for a second.”

Psmith rose. Mike led the way to a quiet corner of the Telegrams Department.

“I tell you, Comrade Jackson,” said Psmith, “I am hard pressed. The fight is beginning to be too much for me. After a grim struggle, after days of unremitting toil, I succeeded yesterday in inducing the man Bristow to abandon that rainbow waistcoat of his. To-day I enter the building, blythe and buoyant, worn, of course, from the long struggle, but seeing with aching eyes the dawn of another, better era, and there is Comrade Bristow in a satin tie. It’s hard, Comrade Jackson, it’s hard, I tell you.”

“Look here, Smith,” said Mike, “I wish you’d go round to the Cash and find out what’s up with old Waller. He’s got the hump about something. He’s sitting there looking absolutely fed up with things. I hope there’s nothing up. He’s not a bad sort. It would be rot if anything rotten’s happened.”

Psmith began to display a gentle interest.

“So other people have troubles as well as myself,” he murmured musingly. “I had almost forgotten that. Comrade Waller’s misfortunes cannot but be trivial compared with mine, but possibly it will be as well to ascertain their nature. I will reel round and make inquiries.”

“Good man,” said Mike. “I’ll wait here.”

Psmith departed, and returned, ten minutes later, looking more serious than when he had left.

“His kid’s ill, poor chap,” he said briefly. “Pretty badly too, from what I can gather. Pneumonia. Waller was up all night. He oughtn’t to be here at all to-day. He doesn’t know what he’s doing half the time. He’s absolutely fagged out. Look here, you’d better nip back and do as much of the work as you can. I shouldn’t talk to him much if I were you. Buck along.”

Mike went. Mr. Waller was still sitting staring out across the aisle. There was something more than a little gruesome in the sight of him. He wore a crushed, beaten look, as if all the life and fight had gone out of him. A customer came to the desk to cash a cheque. The cashier shovelled the money to him under the bars with the air of one whose mind is elsewhere. Mike could guess what he was feeling, and what he was thinking about. The fact that the snub-nosed Edward was, without exception, the most repulsive small boy he had ever met in this world, where repulsive small boys crowd and jostle one another, did not interfere with his appreciation of the cashier’s state of mind. Mike’s was essentially a sympathetic character. He had the gift of intuitive understanding, where people of whom he was fond were concerned. It was this which drew to him those who had intelligence enough to see beyond his sometimes rather forbidding manner, and to realize that his blunt speech was largely due to shyness. In spite of his prejudice against Edward, he could put himself into Mr. Waller’s place, and see the thing from his point of view.

Psmith’s injunction to him not to talk much was unnecessary. Mike, as always, was rendered utterly dumb by the sight of suffering. He sat at his desk, occupying himself as best he could with the driblets of work which came to him.

Mr. Waller’s silence and absentness continued unchanged. The habit of years had made his work mechanical. Probably few of the customers who came to cash cheques suspected that there was anything the matter with the man who paid them their money. After all, most people look on the cashier of a bank as a sort of human slot-machine. You put in your cheque, and out comes money. It is no affair of yours whether life is treating the machine well or ill that day.

The hours dragged slowly by, till five o’clock struck, and the cashier, putting on his coat and hat, passed silently out through the swing-doors. He walked listlessly. He was evidently tired out.

Mike shut his ledger with a vicious bang, and went across to find Psmith. He was glad the day was over.

CHAPTER XX.

concerning a cheque.

HINGS never happen

quite as one expects them to. Mike came to the office next morning prepared for

a repetition of the previous day. He was amazed to find the cashier not merely

cheerful, but even exuberantly cheerful. Edward, it appeared, had rallied in

the afternoon, and, when his father had got home, had been out of danger. He

was now going along excellently, and had stumped Ada, who was nursing him, with

a question about the Thirty Years’ War, only a few minutes before his father

had left to catch his train. The cashier was overflowing with happiness and

goodwill towards his species. He greeted customers with bright remarks on the

weather, and snappy views on the leading events of the day; the former tinged with

optimism, the latter full of a gentle spirit of toleration. His attitude

towards the latest actions of His Majesty’s Government was that of one who felt

that, after all, there was probably some good even in the vilest of his fellow

creatures, if one could only find it.

HINGS never happen

quite as one expects them to. Mike came to the office next morning prepared for

a repetition of the previous day. He was amazed to find the cashier not merely

cheerful, but even exuberantly cheerful. Edward, it appeared, had rallied in

the afternoon, and, when his father had got home, had been out of danger. He

was now going along excellently, and had stumped Ada, who was nursing him, with

a question about the Thirty Years’ War, only a few minutes before his father

had left to catch his train. The cashier was overflowing with happiness and

goodwill towards his species. He greeted customers with bright remarks on the

weather, and snappy views on the leading events of the day; the former tinged with

optimism, the latter full of a gentle spirit of toleration. His attitude

towards the latest actions of His Majesty’s Government was that of one who felt

that, after all, there was probably some good even in the vilest of his fellow

creatures, if one could only find it.

Altogether, the cloud had lifted from the Cash Department. All was joy, jollity and song.

“The attitude of Comrade Waller,” said Psmith, on being informed of the change, “is reassuring. I may now think of my own troubles. Comrade Bristow has blown into the office to-day in patent leather boots with white kid uppers, as I believe the technical term is. Add to that the fact that he is still wearing the satin tie, the waistcoat, and the ring, and you will understand why I have definitely decided this morning to abandon all hope of his reform. Henceforth my services, for what they are worth, are at the disposal of Comrade Bickersdyke. My time from now onward is his. He shall have the full educative value of my exclusive attention. I give Comrade Bristow up. Made straight for the corner-flag, you understand,” he added, as Mr. Rossiter emerged from his lair, “and centred, and Sandy Turnbull headed a beautiful goal. I was just telling Jackson about the match against Blackburn Rovers,” he said to Mr. Rossiter.

“Just so, just so. But get on with your work, Smith. We are a little behind-hand. I think perhaps it would be as well not to leave it just yet.”

“I will leap at it at once,” said Psmith cordially.

Mike went back to his department.

The day passed quickly. Mr. Waller, in the intervals of work, talked a good deal, mostly of Edward, his doings, his sayings, and his prospects. The only thing that seemed to worry Mr. Waller was the problem of how to employ his son’s almost superhuman talents to the best advantage. Most of the goals towards which the average man strives struck him as too unambitious for the prodigy.

By the end of the day Mike had had enough of Edward. He never wished to hear the name again.

We do not claim originality for the statement that things never happen quite as one expects them to. We repeat it now because of its profound truth. The Edward’s pneumonia episode having ended satisfactorily (or, rather, being apparently certain to end satisfactorily, for the invalid, though out of danger, was still in bed), Mike looked forward to a series of days unbroken by any but the minor troubles of life. For these he was prepared. What he did not expect was any big calamity.

At the beginning of the day there were no signs of it. The sky was blue, and free from all suggestions of approaching thunderbolts. Mr. Waller, still chirpy, had nothing but good news of Edward. Mike went for his morning stroll round the office feeling that things had settled down and had made up their mind to run smoothly.

When he got back, barely half an hour later, the storm had burst.

There was no one in the department at the moment of his arrival; but a few minutes later he saw Mr. Waller come out of the manager’s room, and make his way down the aisle.

It was his walk which first gave any hint that something was wrong. It was the same limp, crushed walk which Mike had seen when Edward’s safety still hung in the balance.

As Mr. Waller came nearer, Mike saw that the cashier’s face was deadly pale.

Mr. Waller caught sight of him and quickened his pace.

“Jackson,” he said.

Mike came forward.

“Do you—remember——” he spoke slowly, and with an effort, “do you remember a cheque coming through the day before yesterday for a hundred pounds, with Sir John Morrison’s signature?”

“Yes. It came in the morning, rather late.”

Mike remembered the cheque perfectly well, owing to the amount. It was the only three-figure cheque which had come across the counter during the day. It had been presented just before the cashier had gone out to lunch. He recollected the man who had presented it, a tallish man with a beard. He had noticed him particularly because of the contrast between his manner and that of the cashier. The former had been so very cheery and breezy, the latter so dazed and silent.

“Why?” he said.

“It was a forgery,” muttered Mr. Waller, sitting down heavily.

Mike could not take it in all at once. He was stunned. All he could understand was that a far worse thing had happened than anything he could have imagined.

“A forgery!” he said.

“A forgery. And a clumsy one. Oh, it’s hard. I should have seen it on any other day but that. I could not have missed it. They showed me the cheque in there just now. I could not believe that I had passed it. I don’t remember doing it. My mind was far away. I don’t remember the cheque or anything about it. Yet there it is.”

Once more Mike was tongue-tied. For the life of him he could not think of anything to say. Surely, he thought, he could find something in the shape of words to show his sympathy. But he could find nothing that would not sound horribly stilted and cold. He sat silent.

“Sir John is in there,” went on the cashier. “He is furious. Mr. Bickersdyke, too. They are both furious. I shall be dismissed. I shall lose my place. I shall be dismissed.” He was talking more to himself than to Mike. It was dreadful to see him sitting there, all limp and broken.

“I shall lose my place. Mr. Bickersdyke has wanted to get rid of me for a long time. He never liked me. I shall be dismissed. What can I do? I’m an old man. I can’t make another start. I am good for nothing. Nobody will take an old man like me.”

His voice died away. There was a silence. Mike sat staring miserably in front of him.

Then, quite suddenly, an idea came to him. The whole pressure of the atmosphere seemed to lift. He saw a way out. It was a curious, crooked way, but at that moment it stretched clear and broad before him. He felt light-hearted and excited, as if he were watching the development of some interesting play at the theatre.

He got up, smiling.

The cashier did not notice the movement. Somebody had come in to cash a cheque, and he was working mechanically.

Mike walked up the aisle to Mr. Bickersdyke’s room, and went in.

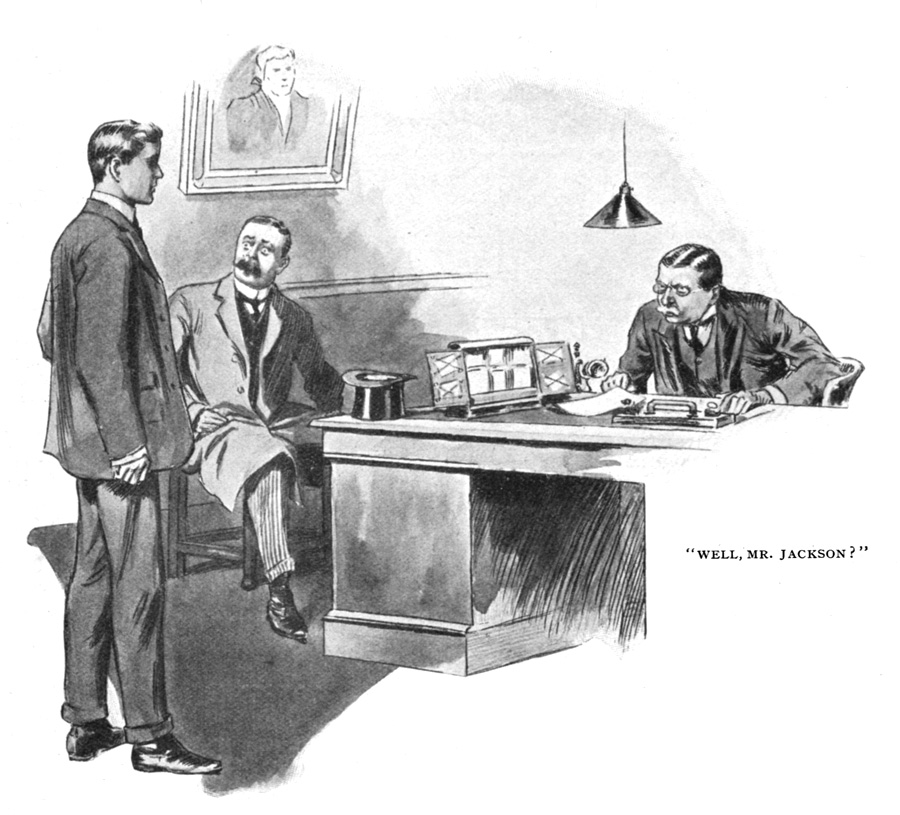

The manager was in his chair at the big table. Opposite him, facing slightly sideways, was a small, round, very red-faced man. Mr. Bickersdyke was speaking as Mike entered.

“I can assure you, Sir John——” he was saying.

He looked up as the door opened.

“Well, Mr. Jackson?”

Mike almost laughed. The situation was tickling him.

“Mr. Waller has told me——” he began.

“I have already seen Mr. Waller.”

“I know. He told me about the cheque. I came to explain.”

“Explain?”

“Yes. He didn’t cash it at all.”

“I don’t understand you, Mr. Jackson.”

“I was at the counter when it was brought in,” said Mike. “I cashed it.”

(To be continued.)

Madame Eulalie’s Rare Plums

Madame Eulalie’s Rare Plums