The Captain, December 1905

CHAPTER IX.

sheen begins his education.

HE “Blue Boar” was a picturesque inn, standing on the bank of

the river Severn. It was much frequented in the summer by fishermen, who spent

their days in punts and their evenings in the old oak parlour, where a picture

in boxing costume of Mr. Joe Bevan, whose brother was the landlord of the inn, gazed

austerely down on them, as if he disapproved of the lamentable want of truth

displayed by the majority of their number. Artists also congregated there to

paint the ivy-covered porch. At the back of the house were bedrooms, to which

the fishermen would make their way in the small hours of a summer morning,

arguing to the last as they stumbled upstairs. One of these bedrooms, larger

than the others, had been converted into a gymnasium for the use of mine

host’s brother. Thither he brought pugilistic aspirants who wished to be

trained for various contests, and it was the boast of the “Blue

Boar” that it had never turned out a loser. A reputation of this kind is

a valuable asset to an inn, and the boxing world thought highly of it, in spite

of the fact that it was off the beaten track. Certainly the luck of the

“Blue Boar” had been surprising.

HE “Blue Boar” was a picturesque inn, standing on the bank of

the river Severn. It was much frequented in the summer by fishermen, who spent

their days in punts and their evenings in the old oak parlour, where a picture

in boxing costume of Mr. Joe Bevan, whose brother was the landlord of the inn, gazed

austerely down on them, as if he disapproved of the lamentable want of truth

displayed by the majority of their number. Artists also congregated there to

paint the ivy-covered porch. At the back of the house were bedrooms, to which

the fishermen would make their way in the small hours of a summer morning,

arguing to the last as they stumbled upstairs. One of these bedrooms, larger

than the others, had been converted into a gymnasium for the use of mine

host’s brother. Thither he brought pugilistic aspirants who wished to be

trained for various contests, and it was the boast of the “Blue

Boar” that it had never turned out a loser. A reputation of this kind is

a valuable asset to an inn, and the boxing world thought highly of it, in spite

of the fact that it was off the beaten track. Certainly the luck of the

“Blue Boar” had been surprising.

Sheen pulled steadily up stream on the appointed day, and after half an hour’s work found himself opposite the little landing-stage at the foot of the inn lawn.

His journey had not been free from adventure. On his way to the town he had almost run into Mr. Templar, and but for the lucky accident of that gentleman’s short sight must have been discovered. He had reached the landing-stage in safety, but he had not felt comfortable until he was well out of sight of the town. It was fortunate for him in the present case that he was being left so severely alone by the school. It was an advantage that nobody took the least interest in his goings and comings.

Having moored his boat and proceeded to the inn, he was directed upstairs by the landlord, who was an enlarged and coloured edition of his brother. From the other side of the gymnasium door came an unceasing and mysterious shuffling sound.

He tapped at the door, and went in.

He found himself in a large, airy room, lit by two windows and a broad skylight. The floor was covered with linoleum. But it was the furniture that first attracted his attention. In a farther corner of the room was a circular wooden ceiling, supported by four narrow pillars. From the centre of this hung a ball, about the size of an ordinary football. To the left, suspended from a beam, was an enormous leather bolster. On the floor, underneath a table bearing several pairs of boxing-gloves, a skipping-rope, and some wooden dumb-bells, was something that looked like a dozen Association footballs rolled into one. All the rest of the room, a space some few yards square, was bare of furniture. In this space a small sweater-clad youth, with a head of light hair cropped very short, was darting about and ducking and hitting out with both hands at nothing, with such a serious, earnest expression on his face that Sheen could not help smiling. On a chair by one of the windows Mr. Joe Bevan was sitting, with a watch in his hand.

As Sheen entered the room the earnest young man made a sudden dash at him. The next moment he seemed to be in a sort of heavy shower of fists. They whizzed past his ear, flashed up from below within an inch of his nose, and tapped him caressingly on the waistcoat. Just as the shower was at its heaviest his assailant darted away again, side-stepped an imaginary blow, ducked another, and came at him once more. None of the blows struck him, but it was with more than a little pleasure that he heard Joe Bevan call “Time!” and saw the active young gentleman sink panting into a seat.

“You and your games, Francis!” said Joe Bevan, reproachfully. “This is a young gentleman from the college come for tuition.”

“Gentleman—won’t mind—little joke—take it in spirit which is—meant,” said Francis, jerkily.

Sheen hastened to assure him that he had not been offended.

“You take your two minutes, Francis,” said Mr. Bevan, “and then have a turn with the ball. Come this way, Mr.——”

“Sheen.”

“Come this way, Mr. Sheen, and I’ll show you where to put on your things.”

Sheen had brought his football clothes with him. He had not put them on for a year.

“That’s the lad I was speaking of. Getting on prime, he is. Fit to fight for his life, as the saying is.”

“What was he doing when I came in?”

“Oh, he always has three rounds like that every day. It teaches you to get about quick. You try it when you get back, Mr. Sheen. Fancy you’re fighting me.”

“Are you sure I’m not interrupting you in the middle of your work?” asked Sheen.

“Not at all, sir, not at all. I just have to rub him down, and give him his shower-bath, and then he’s finished for the day.”

Having donned his football clothes and returned to the gymnasium, Sheen found Francis in a chair, having his left leg vigorously rubbed by Mr. Bevan.

“You fon’ of dargs?” inquired Francis affably, looking up as he came in.

Sheen replied that he was, and, indeed, was possessed of one. The admission stimulated Francis, whose right leg was now under treatment, to a flood of conversation. He, it appeared, had always been one for dargs. Owned two. Answering to the names of Tim and Tom. Beggars for rats, yes. And plucked ’uns? Well—he would like to see, would Francis, a dog that Tim or Tom would not stand up to. Clever, too. Why once——

Joe Bevan cut his soliloquy short at this point by leading him off to another room for his shower-bath; but before he went he expressed a desire to talk further with Sheen on the subject of dogs, and, learning that Sheen would be there every day, said he was glad to hear it. He added that for a brother dog-lover he did not mind stretching a point, so that, if ever Sheen wanted a couple of rounds any day, he, Francis, would see that he got them. This offer, it may be mentioned, Sheen accepted with gratitude, and the extra practice he acquired thereby was subsequently of the utmost use to him. Francis, as a boxer, excelled in what is known in pugilistic circles as shiftiness. That is to say, he had a number of ingenious ways of escaping out of tight corners; and these he taught Sheen, much to the latter’s profit.

But this was later, when the Wrykinian had passed those preliminary stages on which he was now to embark.

The art of teaching boxing really well is a gift, and it is given to but a few. It is largely a matter of personal magnetism, and, above all, sympathy. A man may be a fine boxer himself, up to every move of the game, and a champion of champions, but for all that he may not be a good teacher. If he has not the sympathy necessary for the appreciation of the difficulties experienced by the beginner, he cannot produce good results. A boxing instructor needs three qualities, skill, sympathy, and enthusiasm. Joe Bevan had all three, particularly enthusiasm. His heart was in his work, and he carried Sheen with him. “Beautiful, sir, beautiful,” he kept saying, as he guarded the blows; and Sheen, though too clever to be wholly deceived by the praise, for he knew perfectly well that his efforts up to the present had been anything but beautiful, was nevertheless encouraged, and put all he knew into his hits. Occasionally Joe Bevan would push out his left glove. Then, if Sheen’s guard was in the proper place and the push did not reach its destination, Joe would mutter a word of praise. If Sheen dropped his right hand, so that he failed to stop the blow, Bevan would observe, “Keep that guard up, sir!” with almost a pained intonation, as if he had been disappointed in a friend.

The constant repetition of this maxim gradually drove it into Sheen’s head, so that towards the end of the lesson he no longer lowered his right hand when he led with his left; and he felt the gentle pressure of Joe Bevan’s glove less frequently. At no stage of a pupil’s education did Joe Bevan hit him really hard, and in the first few lessons he could scarcely be said to hit him at all. He merely rested his glove against the pupil’s face. On the other hand, he was urgent in imploring the pupil to hit him as hard as he could.

“Don’t be too kind, sir,” he would chant, “I don’t mind being hit. Let me have it. Don’t flap. Put it in with some weight behind it.” He was also fond of mentioning that extract from Polonius’ speech to Laertes, which he had quoted to Sheen on their first meeting.

Sheen finished his first lesson feeling hotter than he had ever felt in his life.

“Hullo, sir, you’re out of condition,” commented Mr. Bevan. “Have a bit of a rest.”

Once more Sheen had learnt the lesson of his weakness. He could hardly realise that he had only begun to despise himself in the last fortnight. Before then, he had been, on the whole, satisfied with himself. He was brilliant at work, and would certainly get a scholarship at Oxford or Cambridge when the time came; and he had specialised in work to the exclusion of games. It is bad to specialise in games to the exclusion of work, but of the two courses the latter is probably the less injurious. One gains at least health by it.

But Sheen now understood thoroughly, what he ought to have learned from his study of the Classics, that the happy mean was the thing at which to strive. And for the future he meant to aim at it. He would get the Gotford, if he could, but also would he win the house boxing at his weight.

After he had rested he discovered the use of the big ball beneath the table. It was soft, but solid and heavy. By throwing this—the medicine-ball, as they call it in the profession—at Joe Bevan, and catching it, Sheen made himself very hot again, and did the muscles of his shoulders a great deal of good.

“That’ll do for to-day, then, sir,” said Joe Bevan. “Have a good rub down to-night, or you’ll find yourself very stiff in the morning.”

“Well, do you think I shall be any good?” asked Sheen.

“You’ll do fine, sir. But remember what Shakespeare says.”

“About vaulting ambition?”

“No, sir, no. I meant what Hamlet says to the players. ‘Nor do not saw the air too much, with your hand, thus, but use all gently.’ That’s what you’ve got to remember in boxing, sir. Take it easy. Easy and cool does it, and the straight left beats the world.”

Sheen paddled quietly back to the town with the stream, pondering over this advice. He felt that he had advanced another step. He was not foolish enough to believe that he knew anything about boxing as yet, but he felt that it would not be long before he did.

CHAPTER X.

sheen’s progress.

HEEN improved. He took to boxing as he had taken to fives. He found that

his fives helped him. He could get about on his feet quickly, and his eye was

trained to rapid work.

HEEN improved. He took to boxing as he had taken to fives. He found that

his fives helped him. He could get about on his feet quickly, and his eye was

trained to rapid work.

His second lesson was not encouraging. He found that he had learned just enough to make him stiff and awkward, and no more. But he kept on, and by the end of the first week Joe Bevan declared definitely that he would do, that he had the root of the matter in him, and now required only practice.

“I wish you could see like I can how you’re improving,” he said at the end of the sixth lesson, as they were resting after five minutes’ exercise with the medicine-ball. “I get four blows in on some of the gentlemen I teach to one what I get in on you. But it’s like riding. When you can trot, you look forward to when you can gallop. And when you can gallop, you can’t see yourself getting on any further. But you’re improving all the time.”

“But I can’t gallop yet?” said Sheen.

“Well, no, not gallop exactly, but you’ve only had six lessons. Why, in another six weeks, if you come regular, you won’t know yourself. You’ll be making some of the young gentlemen at the college wish they had never been born. You’ll make babies of them, that’s what you’ll do.”

“I’ll bet I couldn’t, if I’d learnt with some one else,” said Sheen, sincerely. “I don’t believe I should have learnt a thing if I’d gone to the school instructor.”

“Who is your school instructor, sir?”

“A man named Jenkins. He used to be in the army.”

“Well, there, you see, that’s what it is. I know old George Jenkins. He used to be a pretty good boxer in his time, but, there! boxing’s a thing, like everything else, that moves with the times. We used to go about in iron trucks. Now we go in motor-cars. Just the same with boxing. What you’re learning now is the sort of boxing that wins championship fights nowadays. Old George, well, he teaches you how to put your left out, but, my golly, he doesn’t know any tricks. He hasn’t studied it same as I have. It’s the ring-craft that wins battles. Now, sir, if you’re ready.”

They put on the gloves again. When the round was over, Mr. Bevan had further comments to make.

“You don’t hit hard enough, sir,” he said. “Don’t flap. Let it come straight out with some weight behind it. You want to be earnest in the ring. The other man’s going to do his best to hurt you, and you’ve got to stop him. One good punch is worth twenty taps. You hit him. And when you’ve hit him, don’t you go back; you hit him again. They’ll only give you three rounds in any competition you go in for, so you want to do the work you can while you’re at it.”

As the days went by, Sheen began to imbibe some of Joe Bevan’s rugged philosophy of life. He began to understand that the world is a place where every man has to look after himself, and that it is the stronger hand that wins. That sentence from Hamlet which Joe Bevan was so fond of quoting practically summed up the whole duty of man—and boy too. One should not seek quarrels, but, “being in,” one should do one’s best to ensure that one’s opponent thought twice in future before seeking them. These afternoons at the “Blue Boar” were gradually giving Sheen what he had never before possessed—self-confidence. He was beginning to find that he was capable of something after all, that in an emergency he would be able to keep his end up. The feeling added a zest to all that he did. His work in school improved. He looked at the Gotford no longer as a prize which he would have to struggle to win. He felt that his rivals would have to struggle to win it from him.

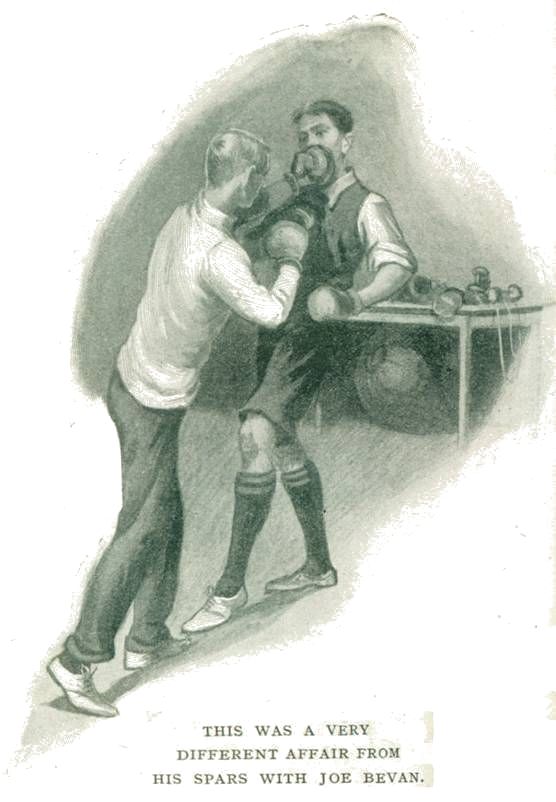

After his twelfth lesson, when he had learned the ground work of the art, and had begun to develop a style of his own, like some nervous batsman at cricket who does not show his true form till he has been at the wickets for several overs, the dog-loving Francis gave him a trial. This was a very different affair from his spars with Joe Bevan. Frank Hunt was one of the cleverest boxers at his weight in England, but he had not Joe Bevan’s gift of hitting gently. He probably imagined that he was merely tapping, and certainly his blows were not to be compared with those he delivered in the exercise of his professional duties; but, nevertheless, Sheen had never felt anything so painful before, not even in his passage of arms with Albert. He came out of the encounter with a swollen lip and a feeling that one of his ribs was broken, and he had not had the pleasure of landing a single blow upon his slippery antagonist, who flowed about the room like quicksilver. But he had not flinched, and the statement of Francis, as they shook hands, that he had “done varry well,” was as balm. Boxing is one of the few sports where the loser can feel the same thrill of triumph as the winner. There is no satisfaction equal to that which comes when one has forced oneself to go through an ordeal from which one would have liked to have escaped.

“Capital, sir, capital,” said Joe Bevan. “I wanted to see whether you would lay down or not when you began to get a few punches. You did capitally, Mr. Sheen.”

“I didn’t hit him much,” said Sheen with a laugh.

“Never mind, sir, you got hit, which was just as good. Some of the gentlemen I’ve taught wouldn’t have taken half that. They’re all right when they’re on top and winning, and to see them shape you’d say to yourself, By George, here’s a champion. But let ’em get a punch or two, and hullo! says you, what’s this? They don’t like it. They lay down. But you kept on. There’s one thing, though, you want to keep that guard up when you duck. You slip him that way once. Very well. Next time he’s waiting for you. He doesn’t hit straight. He hooks you, and you don’t want many of those.”

Sheen enjoyed his surreptitious visits to the “Blue Boar.” Twice he escaped being caught in the most sensational way; and once Mr. Spence, who looked after the Wrykyn cricket and gymnasium, and played everything equally well, nearly caused complications by inviting Sheen to play fives with him after school. Fortunately the Gotford afforded an excellent excuse. As the time for the examination drew near, those who had entered for it were accustomed to become hermits to a great extent, and to retire after school to work in their studies.

“You mustn’t overdo it, Sheen,” said Mr. Spence. “You ought to get some exercise.”

“Oh, I do, sir,” said Sheen. “I still play fives, but I play before breakfast now.”

He had had one or two games with Harrington of the School House, who did not care particularly whom he played with so long as his opponent was a useful man. Sheen being one of the few players in the school who were up to his form, Harrington ignored the cloud under which Sheen rested. When they met in the world outside the fives-courts Harrington was polite, but made no overtures of friendship. That, it may be mentioned, was the attitude of every one who did not actually cut Sheen. The exception was Jack Bruce, who had constituted himself audience to Sheen, when the latter was practising the piano, on two further occasions. But then Bruce was so silent by nature that for all practical purposes he might just as well have cut Sheen like the others.

“We might have a game before breakfast some time, then,” said Mr. Spence.

He had noticed, being a master who did notice things, that Sheen appeared to have few friends, and had made up his mind that he would try and bring him out a little. Of the real facts of the case, he knew, of course, nothing.

“I should like to, sir,” said Sheen.

“Next Wednesday?”

“All right, sir.”

“I’ll be there at seven. If you’re before me, you might get the second court, will you?”

The second court from the end nearest the boarding-house was the best of the half-dozen fives-courts at Wrykyn. After school sometimes you would see fags racing across the gravel to appropriate it for their masters. The rule was that whoever first pinned to the door a piece of paper with his name on it was the legal owner of the court—and it was a stirring sight to see a dozen fags fighting to get at the door. But before breakfast the court might be had with less trouble.

Meanwhile, Sheen paid his daily visits to the “Blue Boar,” losing flesh and gaining toughness with every lesson. The more he saw of Joe Bevan the more he liked him, and appreciated his strong, simple outlook on life. Shakespeare was a great bond between them. Sheen had always been a student of the Bard, and he and Joe would sit on the little verandah of the inn, looking over the river, until it was time for him to row back to the town, quoting passages at one another. Joe Bevan’s knowledge, of the plays, especially the tragedies, was wide, and at first inexplicable to Sheen. It was strange to hear him declaiming long speeches from Macbeth or Hamlet and to think that he was by profession a pugilist. One evening he explained his curious erudition. In his youth, before he took to the ring in earnest, he had travelled with a Shakespearean repertory company. “I never played a star part,” he confessed, “but I used to come on in the Battle of Bosworth and in Macbeth’s castle and what not. I’ve been First Citizen sometimes. I was the carpenter in ‘Julius Cæsar.’ That was my biggest part. ‘Truly sir, in respect of a fine workman, I am but, as you would say, a cobbler.’ But somehow the stage—well . . . you know what it is, sir. Leeds one week, Manchester the next, Brighton the week after, and travelling all Sunday. It wasn’t quiet enough for me.”

The idea of becoming a professional pugilist for the sake of peace and quiet tickled Sheen. “But I’ve always read Shakespeare ever since then,” continued Mr. Bevan, “and I always shall read him.”

It was on the next day that Mr. Bevan made a suggestion which drew confidences from Sheen, in his turn.

“What you want now, sir,” he said, “is to practise on someone of about your own form, as the saying is. Isn’t there some gentleman friend of yours at the college who would come here with you?”

They were sitting on the verandah when he asked this question. It was growing dusk, and the evening seemed to invite confidences. Sheen, looking out across the river and avoiding his friend’s glance, explained just what it was that made it so difficult for him to produce a gentleman friend at that particular time. He could feel Mr. Bevan’s eye upon him, but he went through with it till the thing was told—boldly, and with no attempt to smooth over any of the unpleasant points.

“Never you mind, sir,” said Mr. Bevan consolingly, as he finished. “We all lose our heads sometimes. I’ve seen the way you stand up to Francis, and I’ll eat—I’ll eat the medicine-ball if you’re not as plucky as anyone. It’s simply a question of keeping your head. You wouldn’t do a thing like that again, not you. Don’t you worry yourself, sir. We’re all alike when we get bustled. We don’t know what we’re doing, and by the time we’ve put our hands up and got into shape, why, it’s all over, and there you are. Don’t you worry yourself, sir.”

“You’re an awfully good sort, Joe,” said Sheen gratefully.

CHAPTER XI.

a small incident.

AILING a gentleman friend, Mr. Bevan was obliged to do what he could by

means of local talent. On Sheen’s next visit he was introduced to a burly

youth of his own age, very taciturn and apparently ferocious. He, it seemed,

was the knife and boot boy at the “Blue Boar,” “did a

bit” with the gloves, and was willing to spar with Sheen provided Mr.

Bevan made it all right with the guv’nor; saw, that is so say, that he

did not get into trouble for passing in unprofessional frivolity moments which

should have been sacred to knives and boots. These terms having been agreed to,

he put on the gloves.

AILING a gentleman friend, Mr. Bevan was obliged to do what he could by

means of local talent. On Sheen’s next visit he was introduced to a burly

youth of his own age, very taciturn and apparently ferocious. He, it seemed,

was the knife and boot boy at the “Blue Boar,” “did a

bit” with the gloves, and was willing to spar with Sheen provided Mr.

Bevan made it all right with the guv’nor; saw, that is so say, that he

did not get into trouble for passing in unprofessional frivolity moments which

should have been sacred to knives and boots. These terms having been agreed to,

he put on the gloves.

For the first time since he had begun his lessons, Sheen experienced an attack of his old shyness and dislike of hurting other people’s feelings. He could not resist the thought that he had no grudge against the warden of the knives and boots. He hardly liked to hit him.

The other, however, did not share this prejudice. He rushed at Sheen with such determination that almost the first warning the latter had that the contest had begun was the collision of the back of his head with the wall. Out in the middle of the room he did better, and was beginning to hold his own, in spite of a rousing thump on his left eye, when Joe Bevan called “Time!” A second round went off in much the same way. His guard was more often in the right place, and his leads less wild. At the conclusion of the round, pressure of business forced his opponent to depart, and Sheen wound up his lesson with a couple of minutes at the punching-ball. On the whole, he was pleased with his first spar with someone who was really doing his best and trying to hurt him. With Joe Bevan and Francis there was always the feeling that they were playing down to him. Joe Bevan’s gentle taps, in particular, were a little humiliating. But with his late opponent all had been serious. It had been a real test, and he had come through it very fairly. On the whole, he had taken more than he had given—his eye would look curious to-morrow—but already he had thought out a way of foiling the burly youth’s rushes. Next time he would really show his true form.

The morrow, on which Sheen expected his eye to look curious, was the day he had promised to play fives with Mr. Spence. He hoped that at the early hour at which they had arranged to play it would not have reached its worst stage; but when he looked in the glass at a quarter to seven, he beheld a small ridge of purple beneath it. It was not large, nor did it interfere with his sight, but it was very visible. Mr. Spence, however, was a sportsman, and had boxed himself in his time, so there was a chance that nothing would be said.

It was a raw, drizzly morning. There would probably be few fives-players before breakfast, and the capture of the second court should be easy. So it turned out. Nobody was about when Sheen arrived. He pinned his slip of paper to the door, and, after waiting for a short while for Mr. Spence and finding the process chilly, went for a trot round the gymnasium to pass the time.

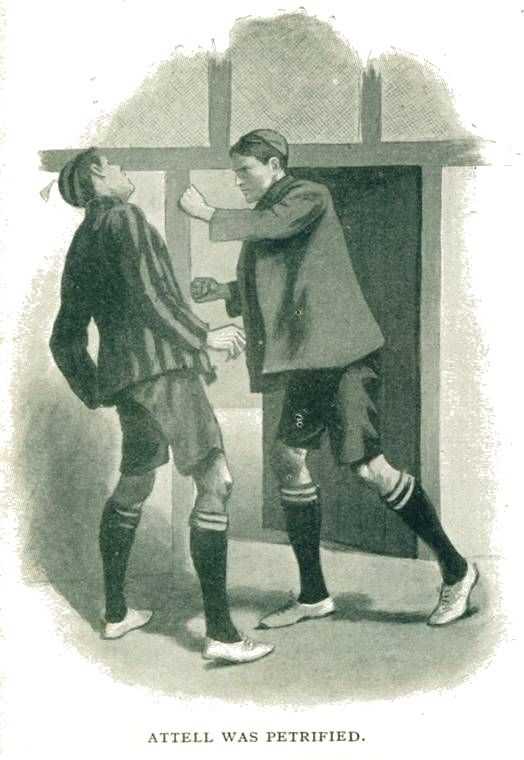

Mr. Spence had not arrived during his absence, but somebody else had. At the door of the second court, gleaming in first-fifteen blazer, sweater, stockings, and honour-cap, stood Attell.

Sheen looked at Attell, and Attell looked through Sheen.

It was curious, thought Sheen, that Attell should be standing in the very doorway of court two. It seemed to suggest that he claimed some sort of ownership. On the other hand, there was his, Sheen’s, paper on the. . . . His eye happened to light on the cement flooring in front of the court. There was a crumpled ball of paper there.

When he had started for his run, there had been no such ball of paper.

Sheen picked it up and straightened it out. On it was written “R. D. Sheen.”

He looked up quickly. In addition to the far-away look, Attell’s face now wore a faint smile, as if he had seen something rather funny on the horizon. But he spake no word.

A curiously calm and contented feeling came upon Sheen. Here was something definite at last. He could do nothing, however much he might resent it, when fellows passed him by as if he did not exist; but when it came to removing his landmark. . . .

“Would you mind shifting a bit?” he said very politely. “I want to pin my paper on the door again. It seems to have fallen down.”

Attell’s gaze shifted slowly from the horizon and gradually embraced Sheen.

“I’ve got this court,” he said.

“I think not,” said Sheen silkily. “I was here at ten to seven, and there was no paper on the door then. So I put mine up. If you move a little, I’ll put it up again.”

“Go and find another court, if you want to play,” said Attell, “and if you’ve got anybody to play with,” he added with a sneer. “This is mine.”

“I think not,” said Sheen.

Attell resumed his inspection of the horizon.

“Attell,” said Sheen.

Attell did not answer.

Sheen pushed him gently out of the way, and tore down the paper from the door.

Their eyes met. Attell, after a moment’s pause, came forward, half menacing, half irresolute; and as he came Sheen hit him under the chin in the manner recommended by Mr. Bevan.

“When you upper-cut,” Mr. Bevan was wont to say, “don’t make it a swing. Just a half-arm jolt’s all you want.”

It was certainly all Attell wanted. He was more than surprised. He was petrified. The sudden shock of the blow, coming as it did from so unexpected a quarter, deprived him of speech: which was, perhaps, fortunate for him, for what he would have said would hardly have commended itself to Mr. Spence, who came up at this moment.

“Well, Sheen,” said Mr. Spence, “here you are. I hope I haven’t kept you waiting. What a morning! You’ve got the court, I hope?”

“Yes, sir,” said Sheen.

He wondered if the master had seen the little episode which had taken place immediately before his arrival. Then he remembered that it had happened inside the court. It must have been over by the time Mr. Spence had come upon the scene.

“Are you waiting for somebody, Attell?” asked Mr. Spence. “Stanning? He will be here directly. I passed him on the way.”

Attell left the court, and they began their game.

“You’ve hurt your eye, Sheen,” said Mr. Spence, at the end of the first game. “How did that happen?”

“Boxing, sir,” said Sheen.

“Oh,” replied Mr. Spence, and to Sheen’s relief he did not pursue his inquiries.

Attell had wandered out across the gravel to meet Stanning.

“Got that court?” inquired Stanning.

“No.”

“You idiot, why on earth didn’t you? It’s the only court worth playing in. Who’s got it?”

“Sheen.”

“Sheen!” Stanning stopped dead. “Do you mean to say you let a fool like Sheen take it from you! Why didn’t you turn him out?”

“I couldn’t,” said Attell. “I was just going to when Spence came up. He’s playing Sheen this morning. I couldn’t very well bag the court when a master wanted it.”

“I suppose not,” said Stanning. “What did Sheen say when you told him you wanted the court?”

This was getting near a phase of the subject which Attell was not eager to discuss.

“Oh, he didn’t say much,” he said.

“Did you do anything?” persisted Stanning.

Attell suddenly remembered having noticed that Sheen was wearing a black eye. This was obviously a thing to be turned to account.

“I hit him in the eye,” he said. “I’ll bet it’s coloured by school-time.”

And sure enough, when school-time arrived, there was Sheen with his face in the condition described, and Stanning hastened to spread abroad this sequel to the story of Sheen’s failings in the town battle. By the end of preparation it had got about the school that Sheen had cheeked Attell, that Attell had hit Sheen, and that Sheen had been afraid to hit him back. At the precise moment when Sheen was in the middle of a warm two-minute round with Francis at the “Blue Boar,” an indignation meeting was being held in the senior day-room at Seymour’s to discuss this latest disgrace to the house.

“This is getting a bit too thick,” was the general opinion. Moreover, it was universally agreed that something ought to be done. The feeling in the house against Sheen had been stirred to a dangerous pitch by this last episode. Seymour’s thought more of their reputation than any house in the school. For years past the house had led on the cricket and football field and off it. Sometimes other houses would actually win one of the cups, but, when this happened, Seymour’s was always their most dangerous rival. Other houses had their ups and downs, were very good one year and very bad the next; but Seymour’s had always managed to maintain a steady level of excellence. It always had a man or two in the School eleven and fifteen, generally supplied one of the School Racquets pair for Queen’s Club in the Easter vac., and when this did not happen always had one of two of the Gym. Six or Shooting Eight, or a few men who had won scholarships at the ’Varsities. The pride of a house is almost keener than the pride of a school. From the first minute he entered the house a new boy was made to feel that, in coming to Seymour’s, he had accepted a responsibility that his reputation was not his own, but belonged to the house. If he did well, the glory would be Seymour’s glory. If he did badly, he would be sinning against the house.

This second story about Sheen, therefore, stirred Seymour’s to the extent of giving the house a resemblance to a hornet’s nest into which a stone had been hurled. After school that day the house literally hummed. The noise of the two day-rooms talking it over could be heard in the road outside. The only bar that stood between the outraged Seymourites and Sheen was Drummond. As had happened before, Drummond resolutely refused to allow anything in the shape of an active protest, and no argument would draw him from this unreasonable attitude, though why it was that he had taken it up he himself could not have said. Perhaps it was that rooted hatred a boxer instinctively acquires of anything in the shape of unfair play that influenced him. He revolted against the idea of a whole house banding together against one of its members.

So even this fresh provocation did not result in any active interference with Sheen; but it was decided that he must be cut even more thoroughly than before.

And about the time when this was resolved, Sheen was receiving the congratulations of Francis on having positively landed a blow upon him. It was an event which marked an epoch in his career.

CHAPTER XII.

dunstable and linton go up the

river.

HERE are some proud, spirited natures which resent rules and laws on

principle as attempts to interfere with the rights of the citizen. As the

Duchess in the play said of her son, who had had unpleasantness with the

authorities at Eton because they had been trying to teach him things,

“Silwood is a sweet boy, but he will not stand the bearing-rein.”

Dunstable was also a sweet boy, but he, too, objected to the bearing-rein. And

Linton was a sweet boy, and he had similar prejudices. And this placing of the

town out of bounds struck both of them simultaneously as a distinct attempt on

the part of the headmaster to apply the bearing-rein.

HERE are some proud, spirited natures which resent rules and laws on

principle as attempts to interfere with the rights of the citizen. As the

Duchess in the play said of her son, who had had unpleasantness with the

authorities at Eton because they had been trying to teach him things,

“Silwood is a sweet boy, but he will not stand the bearing-rein.”

Dunstable was also a sweet boy, but he, too, objected to the bearing-rein. And

Linton was a sweet boy, and he had similar prejudices. And this placing of the

town out of bounds struck both of them simultaneously as a distinct attempt on

the part of the headmaster to apply the bearing-rein.

“It’s all very well to put it out of bounds for the kids,” said Dunstable, firmly, “but when it comes to Us—why, I never heard of such a thing.”

Linton gave it as his opinion that such conduct was quite in a class of its own as regarded cool cheek.

“It fairly sneaks,” said Linton, with forced calm, “the Garibaldi.”

“Kids,” proceeded Dunstable, judicially, “are idiots, and can’t be expected to behave themselves down town. Put the show out of bounds to them if you like. But We——”

“We!” echoed Linton.

“The fact is,” said Dunstable, “it’s a beastly nuisance, but we shall have to go down town and up the river just to assert ourselves. We can’t have the thin end of the wedge coming and spoiling our liberties. We may as well chuck life altogether if we aren’t able to go to the town whenever we like.”

“And Albert will be pining away,” added Linton.

“Hullo, young gentlemen,” said the town boatman, when they presented themselves to him, “what can I do for you?”

“I know it seems strange,” said Dunstable, “but we want a boat. We are the Down-trodden British Schoolboys’ League for Demanding Liberty and seeing that We Get It. Have you a boat?”

The man said he believed he had a boat. In fact, now that he came to think of it, he rather fancied he had one or two. He proceeded to get one ready, and the two martyrs to the cause stepped in.

Dunstable settled himself in the stern, and collected the rudder-lines.

“Hullo,” said Linton, “aren’t you going to row?”

“It may be only my foolish fancy,” replied Dunstable, “but I rather think you’re going to do that. I’ll steer.”

“Beastly slacker,” said Linton. “Anyhow, how far are we going? I’m not going to pull all night.”

“If you row for about half an hour without exerting yourself—and I can trust you not to do that—and then look to your left, you’ll see a certain hostelry, if it hasn’t moved since I was last there. It’s called the ‘Blue Boar.’ We will have tea there, and then I’ll pull gently back, and that will end the programme.”

“Except being caught in the town by half the masters,” said Linton. “Still, I’m not grumbling. This had to be done. Ready?”

“Not just yet,” said Dunstable, looking past Linton and up the landing-stage. “Wait just one second. Here are some friends of ours.”

Linton looked over his shoulder.

“Albert!” he cried.

“And the blighter in the bowler who struck me divers blows in sundry places. Ah, they’ve sighted us.”

“What are you going to do? We can’t have another scrap with them.”

“Far from it,” said Dunstable gently. “Hullo, Albert. And my friend in the moth-eaten bowler! This is well met.”

“You come out here,” said Albert, pausing on the brink.

“Why?” asked Dunstable.

“You see what you’ll get.”

“But we don’t want to see what we’ll get. You’ve got such a narrow mind, Albert—may I call you Bertie? You seem to think that nobody has any pleasures except vulgar brawls. We are going to row up river, and think beautiful thoughts.”

Albert was measuring with his eye the distance between the boat and landing-stage. It was not far. A sudden spring. . . .

“If you want a fight, go up to the school and ask for Mr. Drummond. He’s the gentlemen who sent you to hospital last time. Any time you’re passing, I’m sure he’d——”

Albert leaped.

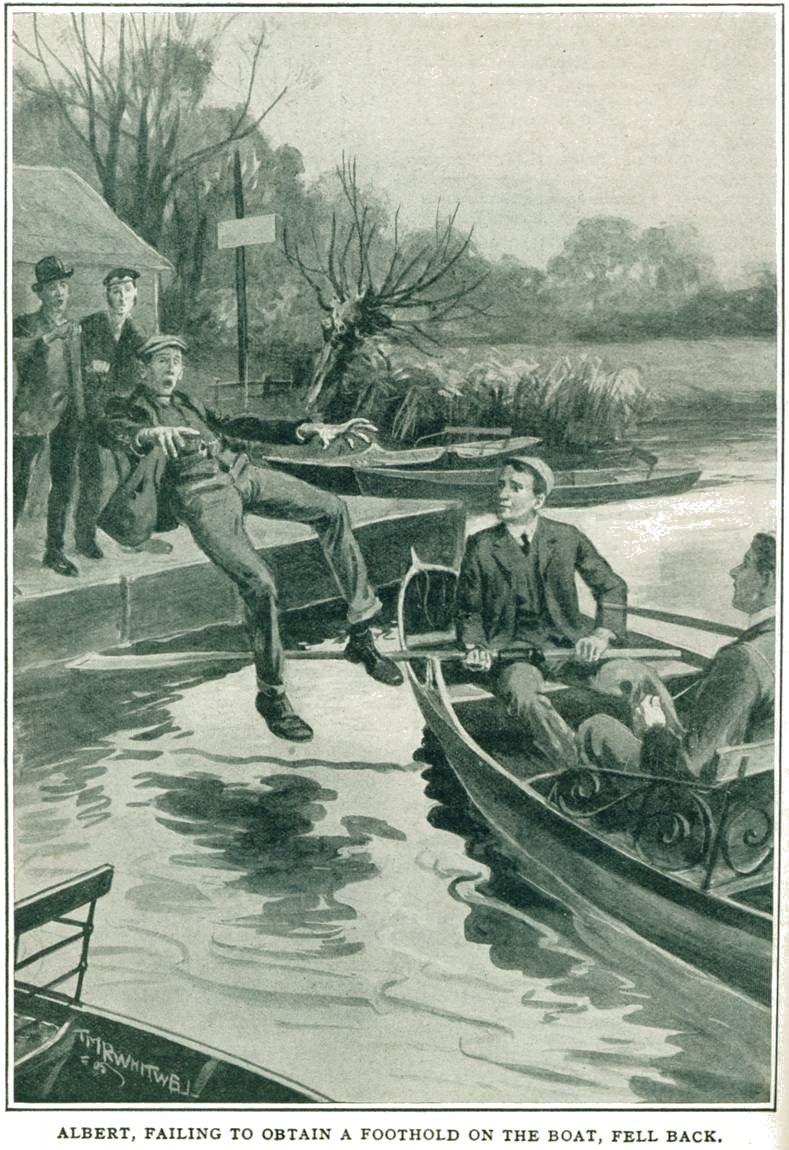

But Linton had had him under observation, and, as he sprung, pushed vigorously with his oar. The gap between boat and shore widened in an instant, and Albert, failing to obtain a foothold on the boat, fell back, with a splash that sent a cascade over his friend and the boatman, into three feet of muddy water. By the time he had scrambled out, his enemies were moving pensively up-stream.

The boatman was annoyed.

“Makin’ me wet and spoilin’ my paint—what yer mean by it?”

“Me and my friend here we want a boat,” said Albert, ignoring the main issue.

“Want a boat! Then you’ll not get a boat. Spoil my cushions, too, would you? What next, I wonder! You go to Smith and ask him for a boat. Perhaps he ain’t so particular about having his cushions——”

“Orl right,” said Albert, “orl right.”

Mr. Smith proved more complaisant, and a quarter of an hour after Dunstable and Linton had disappeared, Albert and his friend were on the water. Moist outside, Albert burned within with a desire for Revenge. He meant to follow his men till he found them. It almost seemed as if there would be a repetition of the naval battle which had caused the town to be put out of bounds. Albert was a quick-tempered youth, and he had swallowed fully a pint of Severn water.

Dunstable and Linton sat for some time in the oak parlour of the “Blue Boar.” It was late when they went out. As they reached the water’s edge Linton uttered a cry of consternation.

“What’s up?” asked Dunstable. “I wish you wouldn’t do that so suddenly. It gives me a start. Do you feel bad?”

“Great Scott! it’s gone.”

“The pain?”

“Our boat. I tied it up to this post.”

“You can’t have done. What’s that boat over there! That looks like ours.”

“No, it isn’t. That was there when we came. I noticed it. I tied ours up here, to this post.”

“This is a shade awkward,” said Dunstable thoughtfully. “You must have tied it up jolly rottenly. It must have slipped away and gone down-stream. This is where we find ourselves in the cart. Right among the ribstons, by Jove. I feel like that Frenchman in the story, who lost his glasses just as he got to the top of the mountain, and missed the view. Altogezzer I do not vish I ’ad kom.”

“I’m certain I tied it up all right. And—why, look! here’s the rope still on the pole, just as I left it.”

For the first time Dunstable seemed interested.

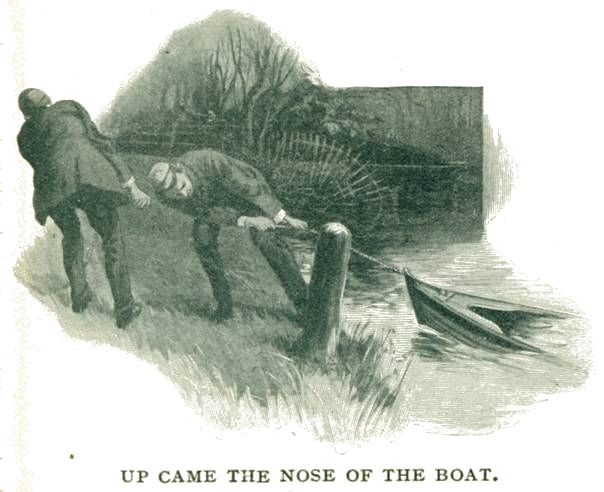

“This is getting mysterious. Did we hire a rowing-boat or a submarine? There’s something on the end of this rope. Give it a tug, and see. There, didn’t you feel it?”

“I do believe,” said Linton in an awed voice, “the thing’s sunk.”

They pulled at the rope together. The waters heaved and broke, and up came the nose of the boat, to sink back with a splash as they loosened their hold.

“There are more things in Heaven and Earth——” said Dunstable, wiping his hands. “If you ask me, I should say an enemy hath done this. A boat doesn’t sink of its own accord.”

“Albert!” said Linton. “The blackguard must have followed us up and done it while we were at tea.”

“That’s about it,” said Dunstable. “And now—how about getting home?”

“I suppose we’d better walk. We shall be hours late for lock-up.”

“You,” said Dunstable, “may walk if you are fond of exercise and aren’t in a hurry. Personally, I’m going back by river.”

“But——”

“That looks a good enough boat over there. Anyhow, we must make it do. One mustn’t be particular for once.”

“But it belongs—what will the other fellow do?”

“I can’t help his troubles,” said Dunstable mildly, “having enough of my own. Coming?”

It was about ten minutes later that Sheen, approaching the waterside in quest of his boat, found no boat there. The time was a quarter to six, and lock-up was at six-thirty.

(To be continued.)

Madame Eulalie’s Rare Plums

Madame Eulalie’s Rare Plums