The Captain, March 1906

CHAPTER XXI.

a good start.

IT was all over in half a minute.

The Tonbridgian was a two-handed fighter of the rushing type, and almost immediately after he had shaken hands, Sheen found himself against the ropes, blinking from a heavy hit between the eyes. Through the mist he saw his opponent sparring up to him, and as he hit he side-stepped. The next moment he was out in the middle again, with his man pressing him hard. There was a quick rally, and then Sheen swung his right at a venture. The blow had no conscious aim. It was purely speculative. But it succeeded. The Tonbridgian fell with a thud.

Sheen drew back. The thing seemed pathetic. He had braced himself up for a long fight, and it had ended in half a minute. His sensations were mixed. The fighting half of him was praying that his man would get up and start again. The prudent half realised that it was best that he should stay down. He had other fights before him before he could call that silver medal his own, and this would give him an invaluable start in the race. His rivals had all had to battle hard in their opening bouts.

The Tonbridgian’s rigidity had given place to spasmodic efforts to rise. He got on one knee, and his gloved hand roamed feebly about in search of a hold. It was plain that he had shot his bolt. The referee signed to his seconds, who ducked into the ring and carried him to his corner. Sheen walked back to his own corner, and sat down. Presently the referee called out his name as the winner, and he went across the ring and shook hands with his opponent, who was now himself again.

He overheard snatches of conversation as he made his way through the crowd to the dressing-room.

“Useful boxer, that Wrykyn boy.”

“Shortest fight I’ve seen here since Hopley won the Heavy-Weights.”

“Fluke, do you think?”

“Don’t know. Came to the same thing in the end, anyhow. Caught him fair.”

“Hard luck on that Tonbridge man. He’s a good boxer, really. Did well here last year.”

Then an outburst of hand-claps drowned the speakers’ voices. A swarthy youth with the Ripton pink and green on his vest had pushed past him and was entering the ring. As he entered the dressing-room he heard the referee announcing the names. So that was the famous Peteiro! Sheen admitted to himself that he looked tough, and hurried into his coat and out of the dressing-room again so as to be in time to see how the Ripton terror shaped.

It was plainly not a one-sided encounter. Peteiro’s opponent hailed from St. Paul’s, a school that has a habit of turning out boxers. At the end of the first round it seemed to Sheen that honours were even. The great Peteiro had taken as much as he had given, and once had been uncompromisingly floored by the Pauline’s left. But in the second round he began to gain points. For a boy of his weight he had a terrific hit with the right, and three applications of this to the ribs early in the round took much of the sting out of the Pauline’s blows. He fought on with undiminished pluck, but the Riptonian was too strong for him, and the third round was a rout. To quote the Sportsman of the following day, “Peteiro crowded in a lot of work with both hands, and scored a popular victory.”

Sheen looked thoughtful at the conclusion of the fight. There was no doubt that Drummond’s antagonist of the previous year was formidable. Yet Sheen believed himself to be the cleverer of the two. At any rate, Peteiro had given no signs of possessing much cunning. To all appearances he was a tough, go-ahead fighter, with a right which would drill a hole in a steel plate. Had he sufficient skill to baffle his (Sheen’s) strong tactics? If only Joe Bevan would come! With Joe in his corner to direct him, he would feel safe.

But of Joe up to the present there were no signs.

Mr. Spence came and sat down beside him.

“Well, Sheen,” he said, “so you won your first fight. Keep it up.”

“I’ll try, sir,” said Sheen.

“What do you think of Peteiro?”

“I was just wondering, sir. He hits very hard.”

“Very hard indeed.”

“But he doesn’t look as if he was very clever.”

“Not a bit. Just a plain slogger. That’s all. That’s why Drummond beat him last year in the Feather-weights. In strength there was no comparison, but Drummond was just too clever for him. You will be the same, Sheen.”

“I hope so, sir,” said Sheen.

After lunch the second act of the performance began. Sheen had to meet a boxer from Harrow who had drawn a bye in the first round of the competition. This proved a harder fight than his first encounter, but by virtue of a stout heart and a straight left he came through it successfully, and there was no doubt as to what the decision would be. Both judges voted for him.

Peteiro demolished a Radleian in his next fight.

There were now three light-weights in the running—Sheen, Peteiro, and a boy from Clifton. Sheen drew the bye, and sparred in an outer room with a soldier, who was inclined to take the thing easily. Sheen, with the thought of the final in his mind, was only too ready to oblige him. They sparred an innocuous three rounds, and the man of war was kind enough to whisper in his ear as they left the room that he hoped he would win the final, and that he himself had a matter of one-and-sixpence with Old Spud Smith on his success.

“For I’m a man,” said the amiable warrior confidentially, “as knows Class when he sees it. You’re Class, sir, that’s what you are.”

This, taken in conjunction with the fact that if the worst came to the worst he had, at any rate, won a bronze medal by getting into the final, cheered Sheen. If only Joe Bevan had appeared he would have been perfectly contented.

But there were no signs of Joe.

CHAPTER XXII.

a good finish.

INAL, Light-Weights,” shouted the referee.

INAL, Light-Weights,” shouted the referee.

A murmur of interest from the ring-side chairs.

“R. D. Sheen, Wrykyn College.”

Sheen got his full measure of applause this time. His victories in the preliminary bouts had won him favour with the spectators.

“J. Peteiro, Ripton School.”

“Go it, Ripton!” cried a voice from near the door. The referee frowned in the direction of this audacious partisan, and expressed a hope that the audience would kindly refrain from comment during the rounds.

Then he turned to the ring again, and announced the names a second time.

“Sheen—Peteiro.”

The Ripton man was sitting with a hand on each knee, listening to the advice of his school instructor, who had thrust head and shoulders through the ropes, and was busy impressing some point upon him. Sheen found himself noticing the most trivial things with extraordinary clearness. In the front row of the spectators sat a man with a parti-coloured tie. He wondered idly what tie it was. It was rather like one worn by members of Templar’s house at Wrykyn. Why were the ropes of the ring red? He rather liked the colour. There was a man lighting a pipe. Would he blow out the match or extinguish it with a wave of the hand? What a beast Peteiro looked. He really was a nigger. He must look out for that right of his. The straight left. Push it out. Straight left ruled the boxing world. Where was Joe? He must have missed the train. Or perhaps he hadn’t been able to get away. Why did he want to yawn, he wondered.

“Time!”

The Ripton man became suddenly active. He almost ran across the ring. A brief handshake, and he had penned Sheen up in his corner before he had time to leave it. It was evident what advice his instructor had been giving him. He meant to force the pace from the start.

The suddenness of it threw Sheen momentarily off his balance. He seemed to be in a whirl of blows. A sharp shock from behind. He had run up against the post. Despite everything, he remembered to keep his guard up, and stopped a lashing hit from his antagonist’s left. But he was too late to keep out his right. In it came, full on the weakest spot on his left side. The pain of it caused him to double up for an instant, and as he did so his opponent uppercut him. There was no rest for him. Nothing that he had ever experienced with the gloves on approached this. If only he could get out of this corner.

Then, almost unconsciously, he recalled Joe Bevan’s advice.

“If a man’s got you in a corner,” Joe had said, “fall on him.”

Peteiro made another savage swing. Sheen dodged it and hurled himself forward.

“Break away,” said a dispassionate official voice.

Sheen broke away, but now he was out of the corner with the whole good, open ring to manœuvre in.

He could just see the Ripton instructor signalling violently to his opponent, and, in reply to the signals, Peteiro came on again with another fierce rush.

But Sheen in the open was a different person from Sheen cooped up in a corner. Francis Hunt had taught him to use his feet. He side-stepped, and, turning quickly, found his man staggering past him, overbalanced by the force of his wasted blow. And now it was Sheen who attacked, and Peteiro who tried to escape. Two swift hits he got in before his opponent could face round, and another as he turned and rushed. Then for a while the battle raged without science all over the ring. Gradually, with a cold feeling of dismay, Sheen realised that his strength was going. The pace was too hot. He could not keep it up. His left counters were losing their force. Now he was merely pushing his glove into the Ripton man’s face. It was not enough. The other was getting to close quarters, and that right of his seemed stronger than ever.

He was against the ropes now, gasping for breath, and Peteiro’s right was thudding against his ribs. It could not last. He gathered all his strength and put it into a straight left. It took the Ripton man in the throat, and drove him back a step. He came on again. Again Sheen stopped him.

It was his last effort. He could do no more. Everything seemed black to him. He leaned against the ropes and drank in the air in great gulps.

“Time!” said the referee.

The word was lost in the shouts that rose from the packed seats.

Sheen tottered to his corner and sat down.

“Keep it up, sir, keep it up,” said a voice. “Bear’t that the opposed may beware of thee. Don’t forget the guard. And the straight left beats the world.”

It was Joe—at the eleventh hour.

With a delicious feeling of content Sheen leaned back in his chair. It would be all right now. He felt that the matter had been taken out of his hands. A more experienced brain than his would look after the generalship of the fight.

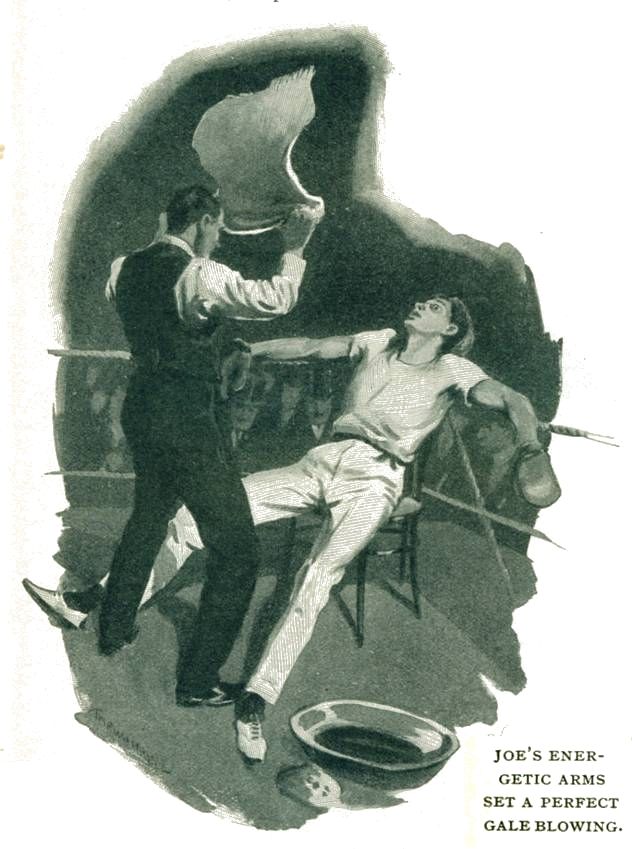

As the moments of the half-minute’s rest slid away he discovered the truth of Joe’s remarks on the value of a good second. In his other fights the flapping of the towel had hardly stirred the hair on his forehead. Joe’s energetic arms set a perfect gale blowing. The cool air revived him. He opened his mouth and drank it in. A spongeful of cold water completed the cure. Long before the call of Time he was ready for the next round.

“Keep away from him, sir,” said Joe, “and score with that left of yours. Don’t try the right yet. Keep it for guarding. Box clever. Don’t let him corner you. Slip him when he rushes. Cool and steady does it. Don’t aim at his face too much. Go down below. That’s the de-partment. And use your feet. Get about quick, and you’ll find he don’t like that. Hullo, says he, I can’t touch him. Then, when he’s tired, go in.”

The pupil nodded with closed eyes.

While these words of wisdom were proceeding from the mouth of Mr. Bevan, another conversation was taking place which would have interested Sheen if he could have heard it. Mr. Spence and the school instructor were watching the final from the seats under the side windows.

“It’s extraordinary,” said Mr. Spence. “The boy’s wonderfully good for the short time he has been learning. You ought to be proud of your pupil.”

“Sir?”

“I was saying that Sheen does you credit.”

“Not me, sir.”

“What! He told me he had been taking lessons. Didn’t you teach him?”

“Never set eyes on him, till this moment. Wish I had, sir. He’s the sort of pupil I could wish for.”

Mr. Spence bent forward and scanned the features of the man who was attending the Wrykinian.

“Why,” he said, “surely that’s Bevan—Joe Bevan! I knew him at Cambridge.”

“Yes, sir, that’s Bevan,” replied the instructor. “He teaches boxing at Wrykyn now, sir.”

“At Wrykyn—where?”

“Up the river—at the ‘Blue Boar,’ sir,” said the instructor, quite innocently—for it did not occur to him that this simple little bit of information was just so much incriminating evidence against Sheen.

Mr. Spence said nothing, but he opened his eyes very wide. Recalling his recent conversation with Sheen, he remembered that the boy had told him he had been taking lessons, and also that Joe Bevan, the ex-pugilist, had expressed a high opinion of his work. Mr. Spence had imagined that Bevan had been a chance spectator of the boy’s skill; but it would now seem that Bevan himself had taught Sheen. This matter, decided Mr. Spence, must be looked into, for it was palpable that Sheen had broken bounds in order to attend Bevan’s boxing-saloon up the river.

For the present, however, Mr. Spence was content to say nothing.

Sheen came up for the second round fresh and confident. His head was clear, and his breath no longer came in gasps. There was to be no rallying this time. He had had the worst of the first round, and meant to make up his lost points.

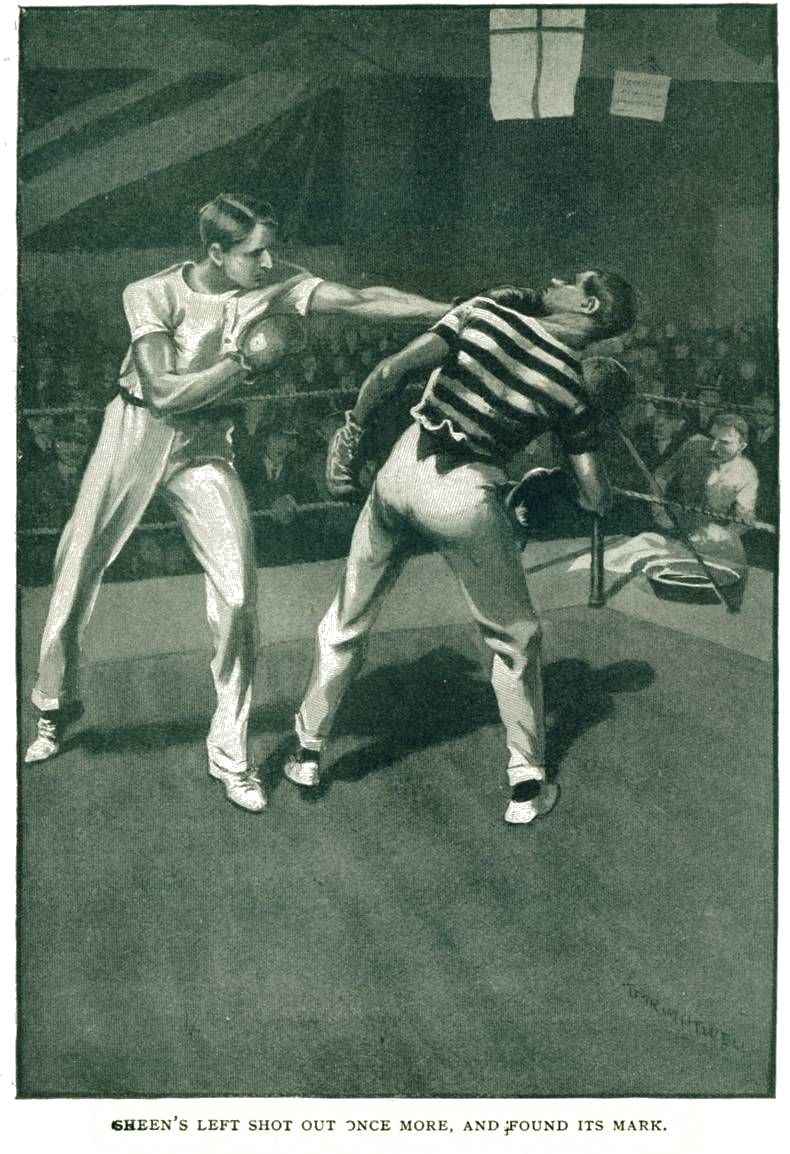

Peteiro, losing no time, dashed in. Sheen met him with a left in the face, and gave way a foot. Again Peteiro rushed, and again he was stopped. As he bored in for the third time Sheen slipped him. The Ripton man paused, and dropped his guard for a moment.

Sheen’s left shot out once more, and found its mark. Peteiro swung his right viciously but without effect. Another swift counter added one more point to Sheen’s score.

Sheen nearly chuckled. It was all so beautifully simple. What a fool he had been to mix it up in the first round. If he only kept his head and stuck to out-fighting he could win with ease. The man couldn’t box. He was nothing more than a slogger. Here he came, as usual, with the old familiar rush. Out went his left. But it missed its billet. Peteiro had checked his rush after the first movement, and now he came in with both hands. It was the first time during the round that he had got to close quarters, and he made the most of it. Sheen’s blows were as frequent, but his were harder. He drove at the body, right and left; and once again the call of Time extricated Sheen from an awkward position. As far as points were concerned he had had the best of the round, but he was very sore and bruised. His left side was one dull ache.

“Keep away from him, sir,” said Joe Bevan. “You were ahead on that round. Keep away all the time unless he gets tired. But if you see me signalling, then go in all you can and have a fight.”

There was a suspicion of weariness about the look of the Ripton champion as he shook hands for the last round. He had not had an expert in his corner, and he was beginning to feel the effects of his hurricane fighting in the opening rounds. He began quietly, sparring for an opening. Sheen led with his left. Peteiro was too late with his guard. Sheen tried again—a double lead. His opponent guarded the first blow, but the second went home heavily on the body, and he gave way a step.

Then from the corner of his eye Sheen saw Bevan gesticulating wildly, so, taking his life in his hands, he abandoned his waiting game, dropped his guard, and dashed in to fight. Peteiro met him doggedly. For a few moments the exchanges were even. Then suddenly the Riptonian’s blows began to weaken. He got home his right on the head, and Sheen hardly felt it. And in a flash there came to him the glorious certainty that the game was his.

He was winning—winning—winning.

. . . . .

“That’s enough,” said the referee.

The Ripton man was leaning against the ropes, utterly spent, at almost the same spot where Sheen had leaned at the end of the first round. The last attack had finished him. His seconds helped him to his corner.

The referee waved his hand.

“Sheen wins,” he said.

And that was the greatest moment of his life.

CHAPTER XXIII.

a surprise for seymour’s.

EYMOUR’S house took in one copy of the Sportsman daily. On the

morning after the Aldershot competition Linton met the paper-boy at the door on

his return from the fives courts, where he had been playing a couple of

before-breakfast games with Dunstable. He relieved him of the house copy, and

opened it to see how the Wrykyn pair had performed in the gymnastics. He did

not expect anything great, having a rooted contempt for both experts, who were small

and, except in the gymnasium, obscure. Indeed, he had gone so far on the

previous day as to express a hope that Biddle, the more despicable of the two,

would fall off the horizontal bar and break his neck. Still he might as well

see where they had come out. After all, with all their faults, they were human

beings like himself, and Wrykinians.

EYMOUR’S house took in one copy of the Sportsman daily. On the

morning after the Aldershot competition Linton met the paper-boy at the door on

his return from the fives courts, where he had been playing a couple of

before-breakfast games with Dunstable. He relieved him of the house copy, and

opened it to see how the Wrykyn pair had performed in the gymnastics. He did

not expect anything great, having a rooted contempt for both experts, who were small

and, except in the gymnasium, obscure. Indeed, he had gone so far on the

previous day as to express a hope that Biddle, the more despicable of the two,

would fall off the horizontal bar and break his neck. Still he might as well

see where they had come out. After all, with all their faults, they were human

beings like himself, and Wrykinians.

The competition was reported in the Boxing column. The first thing that caught his eye was the name of the school among the headlines. “Honours,” said the headline, “for St. Paul’s, Harrow, and Wrykyn.”

“Hullo,” said Linton, “what’s all this?”

Then the thing came on him with nothing to soften the shock. He had folded the paper, and the last words on the half uppermost were, “Final. Sheen beat Peteiro.”

Linton had often read novels in which some important document “swam before the eyes” of the hero or the heroine; but he had never understood the full meaning of the phrase until he read those words, “Sheen beat Peteiro.”

There was no mistake about it. There the thing was. It was impossible for the Sportsman to have been hoaxed. No, the incredible, outrageous fact must be faced. Sheen had been down to Aldershot and won a silver medal! Sheen! Sheen!! Sheen who had—who was—well, who, in a word, was Sheen!!!

Linton read on like one in a dream.

“The light-weights fell,” said the writer, “to a newcomer Sheen, of Wrykyn” (Sheen!), “a clever youngster with a strong defence and a beautiful straight left, doubtless the result of tuition from the middle-weight ex-champion, Joe Bevan, who was in his corner for the final bout. None of his opponents gave him much trouble except Peteiro, of Ripton, whom he met in the final. A very game and determined fight was seen when these two met, but Sheen’s skill and condition discounted the rushing tactics of his adversary, and in the last minute of the third round the referee stopped the encounter.” (Game and determined! Sheen!!) “Sympathy was freely expressed for Peteiro, who has thus been runner-up two years in succession. He, however, met a better man, and paid the penalty. The admirable pluck with which Sheen bore his punishment and gradually wore his man down made his victory the most popular of the day’s programme.”

Well!

Details of the fighting described Sheen as “cutting out the work,” “popping in several nice lefts,” “swinging his right for the point,” and executing numerous other incredible manœuvres.

Sheen!

You caught the name correctly? Sheen, I’ll trouble you.

Linton stared blankly across the school grounds. Then he burst into a sudden yell of laughter.

On that very morning the senior day-room was going to court-martial Sheen for disgracing the house. The resolution had been passed on the previous afternoon, probably just as he was putting the finishing touches to the “most popular victory of the day’s programme.” “This,” said Linton, “is rich.”

He grubbed a little hole in one of Mr. Seymour’s flower-beds, and laid the Sportsman to rest in it. The news would be about the school at nine o’clock, but if he could keep it from the senior day-room till the brief interval between breakfast and school, all would be well, and he would have the pure pleasure of seeing that backbone of the house make a complete ass of itself. A thought struck him. He unearthed the Sportsman, and put it in his pocket.

He strolled into the senior day-room after breakfast.

“Any one seen the Sporter this morning?” he inquired.

No one had seen it.

“The thing hasn’t come,” said some one.

“Good!” said Linton to himself.

At this point Stanning strolled into the room. “I’m a witness,” he said, in answer to Linton’s look of inquiry. “We’re doing this thing in style. I depose that I saw the prisoner cutting off on the—whatever day it was, when he ought to have been saving our lives from the fury of the mob. Hadn’t somebody better bring the prisoner into the dock?”

“I’ll go,” said Linton promptly. “I may be a little time, but don’t get worried. I’ll bring him all right.”

He went upstairs to Sheen’s study, feeling like an impresario about to produce a new play which is sure to create a sensation.

Sheen was in. There was a ridge of purple under his left eye, but he was otherwise intact.

“ ’Gratulate you, Sheen,” said Linton.

For an instant Sheen hesitated. He had rehearsed this kind of scene in his mind, and sometimes he saw himself playing a genial, forgiving, let’s-say-no-more-about-it-we-all-make-mistakes-but-in-future! rôle, sometimes being cold, haughty, and distant, and repelling friendly advances with icy disdain. If anybody but Linton had been the first to congratulate him he might have decided on this second line of action. But he liked Linton, and wanted to be friendly with him.

“Thanks,” he said.

Linton sat down on the table and burst into a torrent of speech.

“You are a man! What did you want to do it for? Where the dickens did you learn to box? And why on earth, if you can win silver medals at Aldershot, didn’t you box for the house and smash up that sidey ass Stanning? I say, look here, I suppose we haven’t been making idiots of ourselves all the time, have we?”

“I shouldn’t wonder,” said Sheen. “How?”

“I mean, you did— What I mean to say is— Oh, hang it, you know! You did cut off when we had that row in the town, didn’t you?”

“Yes,” said Sheen, “I did.”

With that medal in his pocket it cost him no effort to make the confession.

“I’m glad of that. I mean, I’m glad we haven’t been such fools as we might have been. You see, we only had Stanning’s word to go on.”

Sheen started.

“Stanning!” he said. “What do you mean?”

“He was the chap who started the story. Didn’t you know? He told everybody.”

“I thought it was Drummond,” said Sheen blankly. “You remember meeting me outside his study the day after? I thought he told you then.”

“Drummond! Not a bit of it. He swore you hadn’t been with him at all. He was as sick as anything when I said I thought I’d seen you with him.”

“I—” Sheen stopped. “I wish I’d known,” he concluded. Then, after a pause, “So it was Stanning!”

“Yes,—conceited beast. Oh, I say.”

“Um?”

“I see it all now. Joe Bevan taught you to box.”

“Yes.”

“Then that’s how you came to be at the ‘Blue Boar’ that day. He’s the Bevan who runs it.”

“That’s his brother. He’s got a gymnasium up at the top. I used to go there every day.”

“But I say, Great Scott, what are you going to do about that?”

“How do you mean?”

“Why, Spence is sure to ask you who taught you to box. He must know you didn’t learn with the instructor. Then it’ll all come out, and you’ll get dropped on for going up the river and going to the pub.”

“Perhaps he won’t ask,” said Sheen.

“Hope not. Oh, by the way——”

“What’s up?”

“Just remembered what I came up for. It’s an awful rag. The senior day-room are going to court-martial you.”

“Court-martial me!”

“For funking. They don’t know about Aldershot, not a word. I bagged the Sportsman early, and hid it. They are going to get the surprise of their lifetime. I said I’d come up and fetch you.”

“I shan’t go,” said Sheen.

Linton looked alarmed.

“Oh, but I say, you must. Don’t spoil the thing. Can’t you see what a rag it’ll be?”

“I’m not going to sweat downstairs for the benefit of the senior day-room.”

“I say,” said Linton, “Stanning’s there.”

“What!”

“He’s a witness,” said Linton, grinning.

Sheen got up.

“Come on,” he said.

Linton came on.

Down in the senior day-room the court was patiently awaiting the prisoner. Eager anticipation was stamped on its expressive features.

“Beastly time he is,” said Clayton. Clayton was acting as president.

“We shall have to buck up,” said Stanning. “Hullo, here he is at last. Come in, Linton.”

“I was going to,” said Linton, “but thanks all the same. Come along, Sheen.”

“Shut that door, Linton,” said Stanning from his seat on the table.

“All right, Stanning,” said Linton. “Anything to oblige. Shall I bring up a chair for you to rest your feet on?”

“Forge ahead, Clayton,” said Stanning to the president.

The president opened the court-martial in unofficial phraseology.

“Look here, Sheen,” he said, “we’ve come to the conclusion that this has got a bit too thick.”

“You mustn’t talk in that chatty way, Clayton,” interrupted Linton. “ ‘Prisoner at the bar’s’ the right expression to use. Why don’t you let somebody else have a look in? You’re the rottenest president of a court-martial I ever saw.”

“Don’t rag, Linton,” said Clayton, with an austere frown. “This is serious.”

“Glad you told me,” said Linton. “Go on.”

“Can’t you sit down, Linton!” said Stanning.

“I was only waiting for leave. Thanks. You were saying something, Clayton. It sounded pretty average rot, but you’d better unburden your soul.”

The president resumed.

“We want to know if you’ve anything to say——”

“You don’t give him a chance,” said Linton. “You bag the conversation so.”

“—about disgracing the house.”

“By getting the Gotford, you know, Sheen,” explained Linton. “Clayton thinks that work’s a bad habit, and ought to be discouraged.”

Clayton glared, and looked at Stanning. He was not equal to the task of tackling Linton himself.

Stanning interposed.

“Don’t rot, Linton. We haven’t much time as it is.”

“Sorry,” said Linton.

“You’ve let the house down awfully,” said Clayton.

“Yes?” said Sheen.

Linton took the paper out of his pocket, and smoothed it out.

“Seen the Sporter?” he asked casually.

His neighbour grabbed at it.

“I thought it hadn’t come,” he said.

“Good account of Aldershot,” said Linton.

He leaned back in his chair as two or three of the senior day-room collected round the Sportsman.

“Hullo! We won the gym.!”

“Rot! Let’s have a look!”

This tremendous announcement quite eclipsed the court-martial as an object of popular interest. The senior day-room surged round the holder of the paper.

“Give us a chance,” he protested.

“We can’t have. Where is it? Biddle and Smith are simply hopeless. How the dickens can they have got the shield?”

“What a goat you are!” said a voice reproachfully to the possessor of the paper. “Look at this. It says Cheltenham got it. And here we are—seventeenth. Fat lot of shield we’ve won.”

“Then what the deuce does this mean? ‘Honours for St. Paul’s, Harrow, and Wrykyn.’ ”

“Perhaps it refers to the boxing,” suggested Linton.

“But we didn’t send any one up. Look here. Harrow won the Heavies. St. Paul’s got the Middles. Hullo!”

“Great Scott!” said the senior day-room.

There was a blank silence. Linton whistled softly to himself.

The gaze of the senior day-room was concentrated on that ridge of purple beneath Sheen’s left eye.

Clayton was the first to speak. For some time he had been waiting for sufficient silence to enable him to proceed with his presidential duties. He addressed himself to Sheen.

“Look here, Sheen,” he said, “we want to know what you’ve got to say for yourself. You go disgracing the house——”

The stunned senior day-room were roused to speech.

“Oh, chuck it, Clayton.”

“Don’t be a fool, Clayton.”

“Silly idiot!”

Clayton looked round in pained surprise at this sudden withdrawal of popular support.

“You’d better be polite to Sheen,” said Linton; “he won the light-weights at Aldershot yesterday.”

The silence once more became strained.

“Well,” said Sheen, “weren’t you going to court-martial me, or something? Clayton, weren’t you saying something?”

Clayton started. He had not yet grasped the situation entirely; but he realised dimly that by some miracle Sheen had turned in an instant into a most formidable person.

“Er—no,” he said. “No, nothing.”

“The thing seems to have fallen through, Sheen,” said Linton. “Great pity. Started so well, too. Clayton always makes a mess of things.”

“Then I’d just like to say one thing,” said Sheen.

Respectful attention from the senior day-room.

“I only want to know why you can’t manage things of this sort by yourselves, without dragging in men from other houses.”

“Especially men like Stanning,” said Linton. “The same thing occurred to me. It’s lucky Drummond wasn’t here. Remember the last time, you chaps?”

The chaps did. Stanning became an object of critical interest. After all, who was Stanning? What right had he to come and sit on tables in Seymour’s and interfere with the affairs of the house?

The allusion to “last time” was lost upon Sheen, but he saw that it had not improved Stanning’s position with the spectators.

He opened the door.

“Good-bye, Stanning,” he said.

“If I hadn’t hurt my wrist—” Stanning began.

“Hurt your wrist!” said Sheen. “You got a bad attack of Peteiro. That was what was the matter with you.”

“You think that every one’s a funk like yourself,” said Stanning.

“Pity they aren’t,” said Linton; “we should do rather well down at Aldershot. And he wasn’t such a terror after all, Sheen, was he? You beat him in two and a half rounds, didn’t you? Think what Stanning might have done if only he hadn’t sprained his poor wrist just in time.”

“Look here, Linton——”

“Some are born with sprained wrists,” continued the speaker, “some achieve sprained wrists—like Stanning——”

Stanning took a step towards him.

“Don’t forget you’ve a sprained wrist,” said Linton.

“Come on, Stanning,” said Sheen, who was still holding the door open, “you’ll be much more comfortable in your own house. I’ll show you out.”

“I suppose,” said Stanning in the passage, “you think you’ve scored off me.”

“That’s rather the idea,” said Sheen, pleasantly. “You know your way out, don’t you? Good-bye.”

CHAPTER XXIV.

bruce explains.

R. SPENCE was a master with a great deal of sympathy and a highly developed

sense of duty. It was the combination of these two qualities which made it so

difficult for him to determine on a suitable course of action in relation to

Sheen’s out-of-bounds exploits. As a private individual he had nothing but

admiration for the sporting way in which Sheen had fought his up-hill fight. He

felt that he himself in similar circumstances would have broken any number of

school rules. But, as a master, it was his duty, he considered, to report him.

If a master ignored a breach of rules in one case, with which he happened to

sympathise, he would in common fairness be compelled to overlook a similar

breach of rules in other cases, even if he did not sympathise with them. In

which event he would be of small use as a master.

R. SPENCE was a master with a great deal of sympathy and a highly developed

sense of duty. It was the combination of these two qualities which made it so

difficult for him to determine on a suitable course of action in relation to

Sheen’s out-of-bounds exploits. As a private individual he had nothing but

admiration for the sporting way in which Sheen had fought his up-hill fight. He

felt that he himself in similar circumstances would have broken any number of

school rules. But, as a master, it was his duty, he considered, to report him.

If a master ignored a breach of rules in one case, with which he happened to

sympathise, he would in common fairness be compelled to overlook a similar

breach of rules in other cases, even if he did not sympathise with them. In

which event he would be of small use as a master.

On the other hand, Sheen’s case was so exceptional that he might very well compromise to a certain extent between the claims of sympathy and those of duty. If he were to go to the headmaster and state baldly that Sheen had been in the habit for the last half-term of visiting an up-river public-house, the headmaster would get an entirely wrong idea of the matter, and suspect all sorts of things which had no existence in fact. When a boy is accused of frequenting a public-house, the head-magisterial mind leaps naturally to Stale Fumes and the Drunken Stagger.

So Mr. Spence decided on a compromise. He sent for Sheen, and having congratulated him warmly on his victory in the light-weights, proceeded as follows:

“You have given me to understand, Sheen, that you were taught boxing by Bevan?”

“Yes, sir.”

“At the ‘Blue Boar’?”

“Yes, sir.”

“This puts me in a rather difficult position, Sheen. Much as I dislike doing it, I am afraid I shall have to report this matter to the headmaster.”

Sheen said he supposed so. He saw Mr. Spence’s point.

“But I shall not mention the ‘Blue Boar.’ If I did, the headmaster might get quite the wrong impression. He would not understand all the circumstances. So I shall simply mention that you broke bounds by going up the river. I shall tell him the whole story, you understand, and it’s quite possible that you will hear no more of the affair. I’m sure I hope so. But you understand my position?”

“Yes, sir.”

“That’s all, then, Sheen. Oh, by the way, you wouldn’t care for a game of fives before breakfast to-morrow, I suppose?”

“I should like it, sir.”

“Not too stiff?”

“No, sir.”

“Very well, then. I’ll be there by a quarter-past seven.”

Jack Bruce was waiting to see the headmaster in his study at the end of afternoon school.

“Well, Bruce,” said the headmaster, coming into the room and laying down some books on the table, “do you want to speak to me? Will you give your father my congratulations on his victory. I shall be writing to him to-night. I see from the paper that the polling was very even. Apparently one or two voters arrived at the last moment and turned the scale.”

“Yes, sir.”

“It is a most gratifying result. I am sure that, apart from our political views, we should all have been disappointed if your father had not won. Please congratulate him sincerely.”

“Yes, sir.”

“Well, Bruce, and what was it that you wished to see me about?”

Bruce was about to reply when the door opened, and Mr. Spence came in.

“One moment, Bruce,” said the headmaster. “Yes, Spence?”

Mr. Spence made his report clearly and concisely. Bruce listened with interest. He thought it hardly playing the game for the gymnasium master to hand Sheen over to be executed at the very moment when the school was shaking hands with itself over the one decent thing that had been done for it in the course of the athletic year; but he told himself philosophically that he supposed masters had to do these things. Then he noticed with some surprise that Mr. Spence was putting the matter in a very favourable light for the accused. He was avoiding with some care any mention of the “Blue Boar.” When he had occasion to refer to the scene of Sheen’s training, he mentioned it vaguely as a house.

“This man Bevan, who is an excellent fellow and a personal friend of my own, has a house some way up the river.”

Of course a public-house is a house.

“Up the river,” said the headmaster meditatively.

It seemed that that was all that was wrong. The prosecution centred round that point, and no other. Jack Bruce, as he listened, saw his way of coping with the situation.

“Thank you, Spence,” said the headmaster at the conclusion of the narrative. “I quite understand that Sheen’s conduct was very excusable. But— I distinctly said— I placed the upper river out of bounds. . . . Well, I will see Sheen, and speak to him. I will speak to him.”

Mr. Spence left the room.

“Please, sir—” said Jack Bruce.

“Ah, Bruce. I am afraid I have kept you some little time. Yes?

“I couldn’t help hearing what Mr. Spence was saying to you about Sheen, sir. I don’t think he knows quite what really happened.”

“You mean——?”

“Sheen went there by road. I used to take him in my motor.”

“Your—! What did you say, Bruce?”

“My motor-car, sir. That’s to say, my father’s. We used to go together every day.”

“I am glad to hear it. I am glad. Then I need say nothing to Sheen after all. I am glad. . . . But—er—Bruce,” proceeded the headmaster after a pause.

“Yes, sir?”

“Do you—are you in the habit of driving a motor-car frequently?”

“Every day, sir. You see, I am going to take up motors when I leave school, so it’s all education.”

The headmaster was silent. To him the word “Education” meant Classics. There was a Modern side at Wrykyn, and an Engineering side, and also a Science side; but in his heart he recognised but one Education—the Classics. Nothing that he had heard, nothing that he had read in the papers and the monthly reviews had brought home to him the spirit of the age and the fact that Things were not as they used to be so clearly as this one remark of Jack Bruce’s. For here was Bruce admitting that in his spare time he drove motors. And, stranger still, that he did it not as a wild frolic but seriously, with a view to his future career.

“The old order changeth,” thought the headmaster a little sadly.

Then he brought himself back from his mental plunge into the future.

“Well, well, Bruce,” he said, “we need not discuss the merits and demerits of driving motor-cars, need we? What did you wish to see me about?”

“I came to ask if I might get off morning school to-morrow, sir. Those voters who got to the poll just in time and settled the election—I brought them down in the car. And the policeman—he’s a Radical, and voted for Pedder—Mr. Pedder—has sworn—says I was exceeding the speed-limit.”

The headmaster pressed a hand to his forehead, and his mind swam into the future.

“Well, Bruce?” he said at length, in the voice of one whom nothing can surprise now.

“He says I was going twenty-eight miles an hour. And if I can get to the Court to-morrow morning I can prove that I wasn’t. I brought them to the poll in the little runabout.”

“And the—er—little runabout,” said the headmaster, “does not travel at twenty-eight miles an hour?”

“No, sir. It can’t go more than twelve at the outside.”

“Very well, Bruce, you need not come to school to-morrow morning.”

“Thank you, sir.”

The headmaster stood thinking. . . . The new order. . . .

“Bruce,” he said.

“Yes, sir?”

“Tell me, do I look very old?”

Bruce stared.

“Do I look three hundred years old?”

“No, sir,” said Bruce, with the stolid wariness of the boy who fears that a master is subtly chaffing him.

“I feel more, Bruce,” said the headmaster, with a smile. “I feel more. You will remember to congratulate your father for me, won’t you?”

Outside the door Jack Bruce paused in deep reflection.

“Rum!” he said to himself. “Jolly rum!”

. . . . .

On the senior gravel he met Sheen.

“Hullo, Sheen,” he said, “what are you going to do?”

“Drummond wants me to tea with him in the infirmary.”

“It’s all right, then?”

“Yes. I got a note from him during afternoon school. You coming?”

“All right. I say, Sheen, the Old Man’s rather rum sometimes, isn’t he?”

“What’s he been doing now?”

“Oh—nothing. How do you feel after Aldershot? Tell us all about it. I’ve not heard a word yet.”

the end.

Madame Eulalie’s Rare Plums

Madame Eulalie’s Rare Plums