Chapter 15

Where is the Blue Stone?

THE fight on the floor ceased abruptly. As if by mutual consent the two men loosed their hold of each other, and sprang to their feet. The next moment Sam’s antagonist, leaping through the window, had vanished into the night; and Sam followed his example just as the others dashed into the room. Mr. Spinder, entering first, was just in time to see Sam’s back as he dropped over the sill. Bartlett, the porter, was for following him, but Mr. Spinder held him back.

“It is useless, Bartlett,” he said. “They have gone.”

“I might ’ave caught one of ’em, sir,” said Bartlett.

“No, no. There is no need to run risks of that kind. Close the window, Bartlett, will you? Thank you. Have you a match? Thank you. I will just light the gas, and have a look round to see if the scoundrels have taken anything.”

There was the splutter of a match, and the light of the gas flooded the room, making the two boys behind the piano blink as the glare struck their eyes.

“Lord, sir,” came Bartlett’s voice. “They ’aven’t ’arf played old Harry with the furniture!”

Tommy and Jimmy could hear him moving about the room, picking up the various tables and chairs which Sam and the other man had upset in their struggles. When he had completed this task, Mr. Spinder spoke:

“That will do excellently, Bartlett. Thank you. I don’t think those fellows have taken anything. I don’t think there is any need to keep you any longer from your bed. Perhaps you would like a little——”

“Thank you, sir,” said Bartlett’s voice, in what seemed to the two boys rather relieved accents.

There followed the splashing of liquid into a glass, and a murmured “Best of ’ealth, sir,” from Bartlett.

“Good-night, Bartlett,” said Mr. Spinder.

“Good-night, sir.”

“Oh—and, Bartlett.”

“Yes, sir.”

“I think there will be no need of gossip, you understand, about this affair. I would prefer that you said nothing to anybody on the subject.”

“Said nothing to nobody, sir!” Bartlett seemed taken aback by the idea. He had plainly been counting on the episode to furnish him with interesting conversation for weeks to come in the servants’ hall.

“Not a word. There is no need to do so, and it would only make a great deal of fuss and trouble. Nothing has been taken. No harm has been done. So let us allow the matter to drop.”

“Yes, sir,” said Bartlett gloomily.

“Very well. Then good-night, Bartlett.”

“Good-night, sir.”

They heard the porter’s steps retreating down the passage.

When he had gone, Mr. Spinder stayed so still for a while that, if Tommy and Jimmy had not known that he was there, they might well have thought that the room was empty.

At the end, however, of what seemed an age, they heard him move towards the door. He closed it, and walked slowly back to the centre of the room. Here he paused again; finally moving to the big bookshelf that stood against the wall.

He was completely hidden from Jimmy; but Tommy, who was crouching against the same wall as that at which the bookshelf was placed, could follow his movements, which were curious. After standing for some time apparently buried in thought, the master took from the shelf a large book in the second row.

Tommy, who was following his every movement intently, saw that it was either the fifth or sixth book from the end of the shelf. That he had not taken it out with any idea of reading it was soon apparent, for he laid it on a chair at his side, and thrust his hand into the gap between the books. He felt about for a moment, and then withdrew his hand. He looked at some small object in it with satisfaction, and replaced it. Then, having put back the book, he turned out the gas, and left the room.

“Phew!” said Tommy, as the door closed. “I like excitement, but one can have too much of a good thing. This business has been altogether too hot for your uncle. After all, one’s handicapped at school when one tries to work the detective act. Sherlock Holmes wasn’t wondering the whole time that he was hunting for clues whether he would get expelled. That’s what does one in. It hampers one.”

“Is it safe to get up?” asked Jimmy. “Anyhow, I’m going to. I’ve got cramp.”

“Get up as much as you like. Only don’t make too much row about it. Spinder’s just the snaky sort of brute who might be hanging about outside the door. By Jove, what a turn-up those two chaps had! I wish we could have seen it.”

“I wonder that brute didn’t kill Sam, considering that Sam had only one arm to fight with.”

“Are you certain it was Sam?”

“Positive. I knew his voice in a second.”

“Rum thing. One second.”

Tommy wriggled out of his hiding-place, turned on the electric-torch, and went to the bookshelf. He took out the sixth book from the end of the second row, and thrust his hand into the opening, as Mr. Spinder had done. But, beyond getting his fingers very dusty, he accomplished nothing.

“Rum thing,” he said. “I could have sworn I saw him put it back.”

“What’s up?” asked Jimmy.

“Nothing. Look here, we’d better be getting back to bed. I don’t suppose that sheet of ours will be spotted, but it might be, and then the whole game would be up. Come on.”

They opened the door cautiously, and crept down the passage.

“Better put this torch-thing back,” said Tommy. “If Bellamy missed it to-morrow there might be a row.”

They went to the common-room, and restored the electric torch to its locker. Then they crept upstairs.

The sheet was still in its place. Tommy pulled it through the bars, and climbed over the railing. Jimmy followed his example, unhooking the improvised rope when he had reached the top.

“Well,” said Tommy thankfully, as they got into bed, “we’re well out of that. If that’s a sample of a night in this house now that Spinder’s in command, I shall jolly well chuck going about after lights-out. It isn’t good enough. Now I’m going to try and get a bit of sleep. Goodness knows what the time is. It’s not worth while striking a light and looking. It must be about three. I’m aching all over from squatting behind that beastly piano. Good-night.”

“Good-night,” said Jimmy. But he did not go to sleep. Tommy’s breathing soon became heavy and regular. Tommy was the sort of person who could get to sleep in five minutes whenever he wanted to; but Jimmy’s mind was in a whirl. The events of the night had left him utterly perplexed. Who was the man with whom Sam had grappled? Was it the man who had travelled down with Tommy and himself in the train? If so, what had brought him to Mr. Spinder’s room? How did he know that the stone was in the master’s possession?

Sam’s movements were more easily to be accounted for. Jimmy had shown him which was Mr. Spinder’s room; and it was not to be wondered at that Sam had conceived the idea of making an attempt to recover the blue stone for himself.

But what of his antagonist? That problem kept Jimmy perplexed. The fact that Sam had attacked him, added to his words as he grappled with him, showed that Sam had taken him for one of the gang who had been tracking him. But why was he in Mr. Spinder’s room?

A possible solution of the mystery occurred to him after much thought. Mr. Spinder’s was the only window on the ground floor of the building which was not heavily barred. It was, in fact, the only way in for a burglar. Probably the man had intended to use it simply as a means of entrance, before proceeding to search the house. His, Jimmy’s, room must have been his ultimate goal.

Mr. Spinder’s part in the affair had now become doubly sinister. It was now evident that he not only realised the value of the blue stone, but was prepared to keep it in his possession at any cost. His manner had almost suggested that he had expected some such attempt. His instructions, also, to Bartlett to say nothing of the matter showed this plainly. It was clear that it was now war to the knife, a triangular contest with the blue stone as the prize. The atmosphere was charged with veiled hints of danger.

Having arrived at these conclusions, Jimmy fell asleep, and did not wake till Bartlett, as was his custom, opened the iron railing and walked up and down the corridor ringing the getting-up bell.

Chapter 16

When the Black Cat Jumped

THE majority of people, having gone through what Tommy Armstrong had endured in the way of adventure over-night, would probably have chosen to lie low on the following day, thinking that they had had enough excitement for the time being. Tommy’s appetite, however, was accustomed to grow by what it fed on. A little episode like crouching for an hour or so behind a piano, while two burglars entered the housemaster’s study, fought on the floor, and were eventually surprised and routed by the housemaster in person, simply gave Tommy the pleasing feeling that he was living his life as it should be lived. So far from being tired of excitement, he looked about him for the means of manufacturing a further supply.

The instrument was ready to his hand, in the shape of Simpson’s rabbit, Blib. The success of his previous experiment in letting this animal loose in the class-room encouraged him to try the experiment again. Not with Mr. Spinder, who had been present during Blib’s previous visit to the class-room—for Tommy never liked to overdo a thing—but with Herr Steingruber. Piquancy would be added to the situation by the fact that the Herr hated rabbits.

The scheme was, however, wrecked by the unsympathetic attitude of Simpson. Tommy approached him after breakfast.

“I say, Simpson,” he said. “You know, those rabbits of yours don’t get nearly enough exercise.”

“You’ve raced them in the passage pretty well every night since the beginning of term. I don’t know what more you want.”

“Yes, that’s all right as far as it goes, but it doesn’t go nearly far enough. A few sprints up and down a passage aren’t half enough for a healthy rabbit. What they want is a run in the daytime.”

“If you mean——” began Simpson suspiciously.

“I was thinking,” said Tommy airily, “that if you could lend me Blib for the German lesson——”

“I’m blowed if I do. You got the poor brute confiscated last time, and it was only by a fluke that I got him back at all. I’m not going to risk it again.”

“Oh, I say, Simpson, don’t be a cad.”

“I’m hanged if you shall have my rabbit. If you want to bring anything into the class-room, why don’t you borrow Blackie?”

Tommy paused. It was not a bad suggestion. Blackie, the house cat, was a stately animal, whose mission in life was supposed to be the catching of mice. He spent most of his time, however, asleep in the kitchen. Whether he worked while others slept, and made a great slaughter of mice in the small hours of the night, nobody knew. But he could be counted on to have no engagements during the day.

“I will,” said Tommy.

By good luck he chanced to meet Blackie patrolling the passage near the dining-room directly after breakfast. He proceeded to commandeer him.

When Herr Steingruber entered the class-room, Blackie, soothed by a saucer of milk, was asleep in Tommy’s desk.

The German master was in his most jovial mood.

“Ach, my liddle vriendts,” he said, “zo we are again for der ztudying of der Sherman language med dogedder. Led us now broceed our acguaindance with der verbs and deir gurious irregularities do resume. Jutwell, my vriendt, will you der——”

He stopped abruptly, and “pointed” like a dog.

“Ach,” he said, “dell me, is dere in der room a gat?”

It so happened that Herr Steingruber, like Lord Roberts and other famous men, had a constitutional loathing for cats. This curious weakness which attacks some people has never been properly explained, but it undoubtedly exists. Something tells these men when there is a cat in the room, even though they cannot see it.

“A gat, sir?” asked Chutwell.

“Jah. A mitz. A—you know—a gat. I am zure by der gurious veeling in my inzides dot dere was a gat in der room.”

The German master’s moustache was bristling. His eyes gleamed in an agitated way behind his spectacles. Suddenly a well-known sound came from the interior of Tommy’s desk. The Herr started like a war-horse that has heard the trumpet.

“Dere! Did you nod id hear?”

“Hear, sir? What, sir?”

“Der gat-like mewing zound.”

“It might have been a desk squeaking, sir,” suggested Tommy. “Sometimes the nuts get loose, and——”

“No, no, it vos not der desg, it vos der gat-like mewing, dot id vos do mistake imbossible. Ach! Again! Did you nod thad dime id hear?”

This time it was out of the question to deny it. Blackie, having finished his sleep, and finding to his consternation that he was in a sort of wooden box, far too small to give him room to move with any comfort, was now expressing his disgust and disapproval in no uncertain voice. Though muffled by the lid of the desk, the yowls were more than plainly audible.

The class decided on a compromise.

“It does sound like a cat, sir,” agreed Browning. “It’s probably outside in the road.”

“I’m not sure it’s not a sort of bird, sir,” said Tommy, unwilling to concede even as much as Browning. “There are birds which make a noise just like that.”

“No, no, you are nod right, neither of you, my liddle vellows,” said the German master excitedly. “Id vos der gat, nod der bird; und id vos in der room, nod in der road outside. Ach!” He turned towards Tommy. “Armstrong, der gat-like mewing from der direction of you zeems do gome.”

“Me, sir!” said Tommy.

The Herr dashed towards him like a hound that has struck the trail, and stopped in a listening attitude. Tommy leaned heavily on his desk.

“Armstrong,” said the Herr, “berhabs der gat behind der gupboard door is goncealed. Go und loog, my Armsdrong.”

There was a small cupboard against the wall, in which exercise-books, chalk, and other things were kept.

“I don’t think it can be in there, sir.”

“But berhabs id is. Examine der gupboard, my boy.”

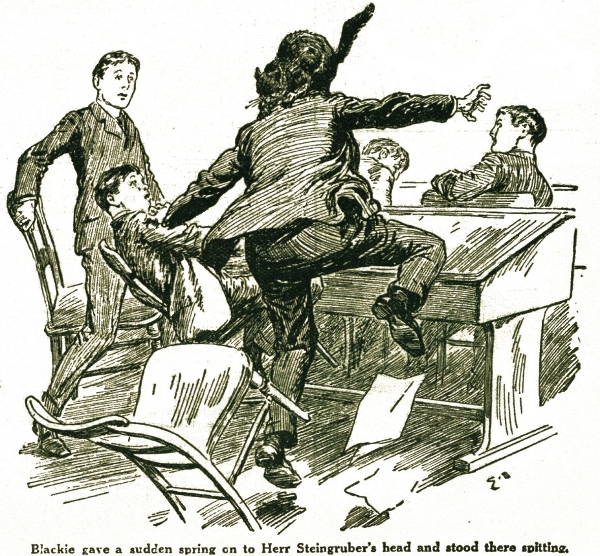

Tommy rose from his seat, and by so doing gave Blackie his chance. The lid, released from the pressure of his arm, rose slowly. The cries increased in volume. For a moment Herr Steingruber did not notice what was happening to the desk. Then it caught his eye, and, as he would have put it himself, he crouched and sprang. He seized the lid of the desk, and flung it open.

“Ach!” he cried. “Zo! As I zusbegded!”

Then he uttered a howl compared with which those of the imprisoned cat were as nothing; for Blackie, rising slowly from his place, gave a sudden spring on to Herr Steingruber’s head, and stood there spitting.

The Herr sprang back, and began to rush around the room like a madman.

“Dake id off! Dake id my head off!”

The class rose from its place as one man. A dozen willing hands removed the indignant Blackie from his perch, and hustled him out of the door. The German master sank into his seat, gasping.

“How it managed to get in there, sir——” began Tommy.

His voice roused the Herr from his stupor.

“Ach, vile Armsdrong,” he roared. “Sgoundrel! Villain! You will for me von tausand lines write. Ach! Dot vill you deach anudder dime nod to in der desg with gunning and wickedness der gat blace. Sgoundrel boy!”

Tommy knew better than to protest at the time. He had seen the Herr like this before, and he knew how to deal with the situation. He resumed his seat quietly, and for the rest of the lesson could have given a lamb points in meekness and docility.

When the lesson was over, and the room empty, he crept to the German master’s desk.

“Please, sir.”

“Vell, Armsdrong.”

The Herr’s voice was stiff with righteous indignation.

“I came to say how sorry I was for——”

“Ach! Doo lade id is for der zorrow und rebendance. You should of dot have before thought. Von tausand lines you will write.”

“Oh, yes, sir,” said Tommy eagerly. “I didn’t want you to let me off the lines. All I wanted was to tell you how sorry I was.”

“Dot vos der right sbirit, Armsdrong,” said the Herr, slightly softened.

“I don’t know how I came to do it, sir. I found the cat in the passage, and brought him in without thinking.”

“Always should you dthink, my boy,” said Herr Steingruber ponderously. “As your boet says, Moch evil has been wrought by want of dhought. Jah, zo.”

“Yes, sir.”

“There was just one other thing, sir,” added Tommy.

Just then the door opened. Mr. Spinder appeared.

“Ah, the class is over? I thought I should find Stewart here. Armstrong, kindly tell Stewart that a visitor is waiting for him in the drawing-room.”

“Yes, sir.”

Mr. Spinder disappeared. Tommy returned to his subject.

“There was just one thing, sir.”

“Vhot vos dot?”

“It’s like this, sir. We are getting up a concert for—for a charitable object. We are all of us going to do something. Some of us will sing, and some recite, and some conjure, and so on.”

“Jah, zo,” said Herr Steingruber, nodding. “I zee. Der zocial goncert for der goot object. Zo.”

“We’ve got a very strong programme, but we all agreed that it would be simply topping——”

“Dopping?”

“You know, sir—great, splendid.”

“Jah, zo.”

“If you would only come and play us something on your ’cello.”

The Herr’s face lit up. He loved his ’cello, which, it may be mentioned, he played really well. His demeanour relaxed at once. All the righteous indignation vanished. He patted Tommy on the head.

“Ach! Zo you vish me on der violoncello do blay, is id? Ach, but shall I nod—you know—what you would zay zboil der fun? You will be der merry lads zinging and choking. Should I nod be in der way, my liddle man?”

For the first time in his life Tommy became aware that he possessed a conscience. He had intended originally to get the Herr to play at the concert with a view to a tremendous rag. The German master’s words made him alter his mind swiftly and completely.

“Of course you won’t, sir,” he said with sincerity. “We shall all be awfully glad if you would play. And,” he added to himself, “if any of those fools try to rag you, I’ll knock their heads off.”

“I shall with bleasure blay,” said Herr Steingruber.

“Thank you, sir. That’s all I wanted to ask you.”

“Ach, but sdob, Armsdrong, sdob. Berhaps a liddle doo severe I was on der boyish biece of fon. Der tausand lines I do gancel. But anodder dime, my boy, do nod der gat indo der glass-room bring.”

“No, sir. Thank you very much, sir.”

Tommy departed to find Jimmy, whom he discovered in the common-room, and despatched in quest of his visitor.

Jimmy wondered, as he went to the drawing-room, who this visitor could be. There was nobody he knew who was likely to come and see him at school. He arrived at the drawing-room, and opened the door. A man was standing, looking out of the window. As Jimmy came in, he turned round, and advanced with a smile.

Jimmy stood still, staring. It was the man who had travelled down with Tommy and himself in the train.

(Another instalment next week, which tells of Jimmy’s adventure with the man. Don’t miss it on any account. Tell your chums about this splendid school story.)

For a note on Lord Roberts, see “The Man Who Disliked Cats” from the Strand magazine.

Madame Eulalie’s Rare Plums

Madame Eulalie’s Rare Plums