Collier’s Weekly, May 22, 1920

The Story—Jill Mariner, engaged to Sir Derek Underhill, is warned by Freddie Rooke of the need of making a good impression on the formidable Lady Underhill, Derek’s mother. The dinner party at which Jill meets Lady Underhill is a failure, and at the theatre afterward Jill incurs the displeasure of Derek by talking to a stranger, who proves to be Wally Mason, the playwright, a childhood friend of Jill’s. The theatre burns down, and during the panic Wally Mason devotes himself to Jill. At the Savoy Hotel, where the two go for supper, Jill suddenly sees Derek and his mother at a near-by table.

IV—Continued

JILL looked at Wally Mason anxiously. Recent events had caused her completely to forget the existence of Lady Underhill. She was always so intensely interested in what she happened to be doing at the moment that she often suffered these temporary lapses of memory. It occurred to her now—too late, as usual—that the Savoy Hotel was the last place in London where she should have come to supper with Wally. It was the hotel where Lady Underhill was staying. She frowned. Life had suddenly ceased to be careless and happy, and had become a thing full of misunderstandings.

“What shall I do?”

Wally Mason started at the sound of her voice. He appeared to be deep in thoughts of his own. “I beg your pardon?”

“What shall I do?”

“I shouldn’t be worried.”

“Derek will be awfully cross.”

Wally’s good-humored mouth tightened almost imperceptibly. “Why?” he said. “There’s nothing wrong in your having supper with an old friend.”

“N—no,” said Jill doubtfully. “But—”

“Derek Underhill,” said Wally reflectively. “Is that Sir Derek Underhill, whose name one’s always seeing in the papers?”

“Derek is in the papers a lot. He’s an M. P. and all sorts of things.”

“Good-looking fellow. Ah, here’s the coffee.”

“I don’t want any, thanks.”

“Nonsense. Why spoil your meal because of this? Do you smoke?”

“No, thanks.”

“Given it up, eh? Dare say you’re wise. Stunts the growth and increases the expenses.”

“Given it up?”

“Don’t you remember sharing one of your father’s cigars with me behind the haystack in the meadow? We cut it in half. I finished my half, but about three puffs were enough for you. Those were happy days!”

“That one wasn’t! Of course I remember it now. I don’t suppose I shall ever forget it.”

“The thing was my fault, as usual. I recollect I dared you.”

“Yes. I always took a dare.”

“Do you still?”

“What do you mean?”

Wally knocked the ash off his cigarette. “Well,” he said slowly, “suppose I were to dare you to get up and walk over to that table and look your fiancé in the eye and say: ‘Stop scowling at my back hair! I’ve a perfect right to be supping with an old friend!’—would you do it?”

“Is he?” said Jill, startled.

“Scowling? Can’t you feel it on the back of your head?” He drew thoughtfully at his cigarette. “If I were you, I should stop that sort of thing at the source. It’s a habit that can’t be discouraged in a husband too early. Scowling is the civilized man’s substitute for wife beating.”

JILL moved uncomfortably in her chair. Her quick temper resented his tone. There was a hostility, a hardly veiled contempt, in his voice which stung her. Derek was sacred. Whoever criticized him presumed. Wally, a few minutes before a friend and an agreeable companion, seemed to her to have changed. He was once more the boy whom she had disliked in the old days. There was a gleam in her eyes which should have warned him, but he went on:

“I should imagine that this Derek of yours is not one of our leading sunbeams. Well, I suppose he could hardly be if that’s his mother, and there is anything in heredity.”

“Please don’t criticize Derek,” said Jill.

“I was only saying—”

“Never mind. I don’t like it.”

A flush crept over Wally’s face. He made no reply, and there fell between them a silence that was like a shadow. Jill sipped her coffee miserably. She was regretting that little spurt of temper. She wished she could have recalled the words. Not that it was the actual words that had torn asunder this gossamer thing, the friendship which they had begun to weave like some fragile web: it was her manner, the manner of the princess rebuking an underling. She knew that, if she had struck him, she could not have offended Wally more deeply. There are some men whose ebullient natures enable them to rise unscathed from the worst snub. Wally, her intuition told her, was not that kind of man.

There was only one way of mending the matter. In these clashes of human temperaments, these sudden storms that spring up out of a clear sky, it is possible sometimes to repair the damage if the psychological moment is resolutely seized by talking rapidly and with detachment on neutral topics. Words have made the rift, and words alone can bridge it. But neither Jill nor her companion could find words, and the silence lengthened grimly. When Wally spoke, it was in the level tones of a polite stranger: “Your friends have gone.”

His voice was the voice in which, when she went on railway journeys, fellow travelers in the carriage inquired of Jill if she would prefer the window up or down. It had the effect of killing her regrets and feeding her resentment. She was a girl who never refused a challenge, and she set herself to be as frigidly polite and aloof as he.

“Really?” she said. “When did they leave?”

“A moment ago.”

The lights gave the warning flicker that announces the arrival of the hour of closing. In the momentary darkness they both rose. Wally scrawled his name across the check which the waiter had insinuated upon his attention. “I suppose we had better be moving?”

They crossed the room in silence. Everybody was moving in the same direction. The broad stairway leading to the lobby was crowded with chattering supper parties. The lights had gone up again.

At the cloak room Wally stopped. “I see Underhill waiting up there,” he said casually. “To take you home, I suppose. Shall we say good night?”

Jill glanced toward the head of the stairs. Derek was there. He was alone. Lady Underhill presumably had gone up to her room in the elevator.

Wally was holding out his hand. His face was stolid, and his eyes avoided hers. “Good-by,” he said.

“Good-by,” said Jill.

She felt curiously embarrassed. At this last moment hostility had weakened, and she was conscious of a desire to make amends. She and this man had been through much together that night, much that was perilous, and much that was pleasant. A sudden feeling of remorse came over her.

“You’ll come and see us, won’t you?” she said a little wistfully. “I’m sure my uncle would like to meet you again.”

“It’s very good of you,” said Wally, “but I’m afraid I shall be going back to America at any moment now.”

Pique, that ally of the devil, regained its slipping grip upon Jill. “Oh, I’m sorry,” she said indifferently. “Well, good-by, then.”

“Good-by.”

“I hope you have a pleasant voyage.”

“Thanks.”

He turned into the cloak room, and Jill went up the stairs to join Derek. She felt angry and depressed, full of a sense of the futility of things. People flashed into one’s life and out again. Where was the sense of it?

DEREK had been scowling, and Derek still scowled. His eyebrows were formidable and his mouth smiled no welcome at Jill as she approached him. The evening, portions of which Jill had found so enjoyable, had contained no pleasant portions for Derek. Looking back over a lifetime whose events had been almost uniformly agreeable, he told himself that he could not recall another day which had gone so completely awry. It had started with the fog. He hated fog. Then had come that meeting with his mother at Charing Cross, which had been enough to upset him by itself. After that, rising to a crescendo of unpleasantness, the day had provided that appalling situation at the Albany, the recollection of which still made him tingle; and there had followed the silent dinner, the boredom of the early part of the play, the fire at the theatre, the undignified scramble for the exits, and now this discovery of the girl whom he was engaged to marry supping at the Savoy with a fellow he didn’t remember ever having seen in his life. All these things combined to induce in Derek a mood bordering on ferocity. His birth and income, combining to make him one of the spoiled children of the world, had fitted him ill for such a series of catastrophes.

Breeding counts. Had he belonged to a lower order of society, Derek would probably have seized Jill by the throat and started to choke her. Being what he was, he merely received her with frozen silence and led her out to the waiting taxicab. It was only when the cab had started on its journey that he found relief in speech.

“Well,” he said, mastering with difficulty an inclination to raise his voice to a shout, “perhaps you will kindly explain?”

Jill had sunk back against the cushions of the cab. The touch of his body against hers always gave her a thrill, half pleasurable, half frightening. She had never met anybody who affected her in this way as Derek did. She moved a little closer, and felt for his hand. But, as she touched it, it retreated—coldly. Her heart sank. It was like being cut in public by somebody very dignified.

“Derek, darling!” Her lips trembled. Others had seen this side of Derek Underhill frequently, for he was a man who believed in keeping the world in its place, but she never. To her he had always been the perfect gracious knight. A little too perfect, perhaps, a trifle too gracious, possibly, but she had been too deeply in love to notice that. “Don’t be cross!”

The English language is the richest in the world, and yet somehow, in moments when words count most, we generally choose the wrong ones. The adjective “cross,” as a description of the Jovelike wrath that consumed his whole being, jarred upon Derek profoundly. It was as though Prometheus, with the vultures tearing his liver, had been asked if he were piqued.

“Cross!”

THE cab rolled on. Lights from lamp-posts flashed in at the windows. It was a pale, anxious little face that they lit up when they shone upon Jill.

“I can’t understand you,” said Derek at last.

Jill noticed that he had not yet addressed her by her name. He was speaking straight out in front of him, as if he were soliloquizing.

“I simply cannot understand you. After what happened before dinner to-night, for you to cap everything by going off alone to supper at a restaurant, where half the people in the room must have known you, with a man—”

“You don’t understand!”

“Exactly! I said I did not understand.” The feeling of having scored a point made Derek feel a little better. “I admit it. Your behavior is incomprehensible. Where did you meet this fellow?”

“I met him at the theatre. He was the author of the play.”

“The man you told me you had been talking to? The fellow who scraped acquaintance with you between the acts?”

“But I found out he was an old friend. I mean, I knew him when I was a child.”

“You didn’t tell me that.”

“I only found it out later.”

“After he had invited you to supper! It’s maddening!” cried Derek, the sense of his wrongs surging back over him. “What do you suppose my mother thought? She asked me who the man with you was. I had to say I didn’t know! What do you suppose she thought?”

It is to be doubted whether anything else in the world could have restored the fighting spirit to Jill’s cowering soul at that moment, but the reference to Lady Underhill achieved this miracle. That deep mutual antipathy which is so much more common than love at first sight had sprung up between the two women at the instant of their meeting. The circumstances of that meeting had caused it to take root and grow. To Jill Derek’s mother was by this time not so much a fellow human being whom she disliked as a something, a sort of force, that made for her unhappiness. She was a menace and a loathing.

“If your mother had asked me that question,” she retorted with spirit, “I should have told her that he was the man who got me safely out of the theatre after you—” She checked herself. She did not want to say the unforgivable thing. “You see,” she said more quietly, “you had disappeared.”

“My mother is an old woman,” said Derek stiffly. “Naturally I had to look after her. I called to you to follow.”

“Oh, I understand. I’m simply trying to explain what happened. I was there all alone, and Wally Mason—”

“Wally!” Derek uttered a short laugh, almost a bark. “It got to Christian names, eh?”

Jill set her teeth. “I told you I knew him as a child. I always called him Wally then.”

“I beg your pardon. I had forgotten.”

“He got me out through the pass door on to the stage and through the stage door.”

Derek was feeling cheated. He had the uncomfortable sensation that comes to men who grandly contemplate mountains and see them dwindle to molehills.

He seized upon the single point in Jill’s behavior that still constituted a grievance.

“There was no need for you to go to supper with the man!” Jovelike wrath had ebbed away to something deplorably like a querulous grumble. “You should have gone straight home. You must have known how anxious I would be about you.”

“Well, really, Derek, dear! You didn’t seem so very anxious! You were having supper yourself quite cozily.”

THE human mind is curiously constituted. It is worthy of record that, despite his mother’s obvious disapproval of his engagement, despite all the occurrences of this dreadful day, it was not till she made this remark that Derek first admitted to himself that, intoxicate his senses as she might, there was a possibility that Jill Mariner was not the ideal wife for him. The idea came and went more quickly than breath upon a mirror. It passed, but it had been. There are men who fear repartee in a wife more keenly than a sword. Derek was one of these. Like most men of single outlook, whose dignity is their most precious possession, he winced from an edged tongue.

“My mother was greatly upset,” he replied coldly. “I thought a cup of soup would do her good. And as for being anxious about you, I telephoned to your house to ask if you had come in.”

“And when,” thought Jill, “they told you I hadn’t you went off to supper!”

She did not speak the words. If she had an edged tongue, she had also the control of it. She had no wish to wound Derek. Whole-hearted in everything she did, she loved him with her whole heart. There might be specks upon her idol—that its feet might be clay she could never believe—but they mattered nothing. She loved him.

“I’m so sorry, dear,” she said. “So awfully sorry! I’ve been a bad girl, haven’t I!”

She felt for his hand again; this time he allowed it to remain stiffly in her grasp. It was like being grudgingly recognized by somebody very dignified who had his doubts about you, but reserved judgment.

The cab drew up at the door of the house in Ovington Square which Jill’s uncle Christopher had settled upon as a suitable address for a gentleman of his standing. (“In a sense, my dear child, I admit, it is Brompton Road, but it opens into Lennox Gardens, which makes it to all intents and purposes Sloane Street.”)

Jill put up her face to be kissed, like a penitent child.

“I’ll never be naughty again!”

For a flickering instant Derek hesitated.

The drive, long as it was, had been too short to restore wholly his equanimity. Then the sense of her nearness, her sweetness, the faint perfume of her hair, and her eyes, shining softly in the darkness so close to his own, overcame him. He crushed her to him.

Jill disappeared into the house with a happy laugh. It had been a terrible day, but it had ended well.

“The Albany,” said Derek to the cabman.

He leaned back against the cushions. His senses were in a whirl. The cab rolled on.

Presently his exalted mood vanished as quickly as it had come. Jill absent always affected him differently from Jill present. He was not a man of strong imagination, and the stimulus of her waned when she was not with him. Long before the cab reached the Albany the frown was back on his face.

Arriving at the Albany, he found Freddie Rooke lying on his spine in a deep armchair. His slippered feet were on the mantelpiece, and he was restoring his wasted tissues with a strong whisky and soda. One of the cigars which Parker, the valet, had stamped with the seal of his approval, was in the corner of his mouth. The “Sporting Times,” with a perusal of which he had been soothing his fluttered nerves, had fallen on the floor beside the chair. He had finished reading, and was now gazing peacefully at the ceiling, his mind a perfect blank.

There was nothing the matter with Freddie.

“Hullo, old thing,” he observed, as Derek entered. “So, you buzzed out of the fiery furnace all right? I was wondering how you had got along. How are you feeling? I’m not the man I was! These things get the old system all stirred up! I’ll do anything in reason to oblige and help things along and all that, but to be called on at a moment’s notice to play Shadrach, Meshach, and Abednego rolled into one, without rehearsal or make-up, is a bit too thick! No, young feller-me-lad! If theatre fires are going to be the fashion this season, the Last of the Rookes will sit quietly at home and play solitaire. Mix yourself a drink of something, old man, or something of that kind. By the way, your jolly old mater— All right? Not even singed? Fine! Make a long arm and gather in a cigar.”

And Freddie, having exerted himself to play the host in a suitable manner, wedged himself more firmly into his chair and blew a cloud of smoke.

Derek sat down. He lit a cigar, and stared silently at the floor. From the mantelpiece Jill’s photograph smiled down, but he did not look at it. Presently his attitude began to weigh upon Freddie.

Freddie Rooke had had a trying evening.

What he wanted just now was merry prattle, and his friend did not seem disposed to contribute his share. He removed his feet from the mantelpiece, and wriggled himself sideways, so that he could see Derek’s face. Its gloom touched him. Apart from his admiration for Derek, he was a warm-hearted young man, and sympathized with affliction when it presented itself to his notice.

“Something on your mind, old bean?” he inquired delicately.

Derek did not answer for a moment.

Then he reflected that, little as he esteemed the other’s mentality, he and Freddie had known each other a long time, and that it would be a relief to confide in some one. And Freddie, moreover, was an old friend of Jill’s and the man who had introduced him to her.

“Yes,” he said.

“I’m listening, old top,” said Freddie. “Release the film.”

Derek drew at his cigar, and watched the smoke as it curled upward to the ceiling.

“It’s about Jill.”

Freddie signified his interest by wriggling still further sideways.

“Jill, eh?”

“Freddie, she’s so dashed impulsive!”

FREDDIE nearly rolled out of his chair. This, he took it, was what writing chappies called a coincidence.

“Rummy, you should say that,” he ejaculated. “I was telling her exactly the same thing myself, only this evening.” He hesitated. “I fancy I can see what you’re driving at, old thing. The watchword is ‘What ho, the mater!’ Yes, no? You’ve begun to get a sort of idea that if Jill doesn’t watch her step, she’s apt to sink pretty low in the betting, what? I know exactly what you mean! You and I know all right that Jill’s a topper. But one can see that to your mater she might seem a bit different. I mean to say, your jolly old mater only, judging by first impressions, and the meeting not having come off quite as scheduled. . . . I say, old man,” he broke off. “Fearfully sorry and all that about that business. You know what I mean! Wouldn’t have had it happen for the world. I take it the mater was a trifle peeved? Not to say perturbed and chagrined? I seemed to notice at dinner.”

“She was furious, of course. She did not refer to the matter when we were alone together, but I knew what she was thinking.”

Derek threw away his cigar. Freddie noted with concern this evidence of an overwrought soul—the thing was only a quarter smoked, and it was a dashed good brand, mark you.

“The whole thing,” he conceded, “was a bit unfortunate.”

Derek began to pace the room.

“Freddie.”

“On the spot, old man!”

“Something’s got to be done!”

“Absolutely!” Freddie nodded solemnly. He had taken this matter greatly to heart. Derek was his best friend, and he had always been extremely fond of Jill. It hurt him to see things going wrong. “I’ll tell you what, old bean. Let me handle this binge for you.”

“You?”

“Me! The Final Rooke!” He jumped up, and leaned against the mantelpiece. “I’m the lad to do it. I’ve known Jill for years. She’ll listen to me. I’ll talk to her like a Dutch uncle and make her understand the general scheme of things. I’ll take her out to tea to-morrow and slang her in no uncertain voice! Leave the whole thing to me, laddie!”

Derek considered.

“It might do some good,” he said.

“Good?” said Freddie. “It’s It, dear boy! It’s a wheeze! You toddle off to bed and have a good sleep. I’ll fix the whole thing for you!”

V

THERE are streets in London into which the sun seems never to penetrate. The majority of them are in the mean neighborhoods of the great railway terminals. They are lean, furtive streets, gray as the January sky, with a sort of arrested decay. They smell of cabbage and are much prowled over by vagrant cats. You will find these streets by the score if you leave the main thoroughfares and take a short cut on your way to Euston, to Paddington, or to Waterloo. But the dingiest and deadliest and most depressing lie round about Victoria. And Daubeny Street, Pimlico, is one of the worst of them all.

On the afternoon following the events recorded, a girl was dressing in the ground-floor room of No. 9, Daubeny Street. A tray bearing the remains of a late breakfast stood on the rickety table beside a bowl of wax flowers. From beneath the table peeped the green cover of a copy of “Variety.” A gray parrot, in a cage by the window, cracked seed and looked out into the room with a satirical eye. He had seen all this so many times before: Nelly Bryant arraying herself in her smartest clothes, to go out and besiege agents in their offices off the Strand. It happened every day. In an hour or two she would come back as usual, say “Oh, Gee!” in a tired sort of voice and then Bill the Parrot’s day proper would begin. He was a bird who liked the sound of his own voice, and he never got the chance of a really sustained conversation till Nelly returned in the evening. “Who cares?” said Bill, and cracked another seed.

If rooms are an indication of the character of their occupants, Nelly Bryant came well out of the test of her surroundings. Nothing can make a London furnished room much less horrible than it intends to be, but Nelly had done her best. The furniture, what there was of it, was of that lodging-house kind which resembles nothing else in the world. But a few little touches here and there, a few instinctively tasteful alterations in the general scheme of things, had given the room almost a cozy air. Later on, with the gas lit, it would achieve something approaching hominess. Nelly, like many another nomad, had taught herself to accomplish a good deal with poor material. On the road in America, she had sometimes made even a bedroom in a small hotel tolerably comfortable, than which there is no greater achievement. Oddly, considering her life, she had a genius for domesticity.

TO-DAY, not for the first time, Nelly was feeling unhappy. Her face that looked back at her out of the mirror was only a moderately pretty face, but loneliness and underfeeding had given it a wistful expression that had charm. Unfortunately, it was not the sort of charm which made a great appeal to the stout, whisky-nourished men who sat behind paper-littered tables, smoking cigars, in the rooms marked “Private” in the offices of theatrical agents. Nelly had been out of a “shop” now for many weeks—ever since, in fact, “Follow the Girl” had finished its long run at the Regal Theatre.

“Follow the Girl,” an American musical comedy, had come over from New York with an American company, of which Nelly had been a humble unit, and, after playing a year in London and some weeks in the number one towns, had returned to New York. It did not cheer Nelly up in the long evenings in Daubeny Street to reflect that, if she had wished, she could have gone home with the rest of the company. A mad impulse had seized her to try her luck in London, and here she was now, marooned.

She picked up her gloves.

“Good-by, boy!” said the parrot, clinging to the bars.

Nelly thrust a finger into the cage and scratched his head.

“Anxious to get rid of me, aren’t you? Well, so long.”

“Good-by, boy!”

“All right, I’m going. Be good!”

“Woof-woof-woof!” barked Bill, not committing himself to any promises.

For some moments after Nelly had gone he remained hunched on his perch, contemplating the infinite. Then he sauntered along to the seed box and took some more light nourishment. He always liked to spread his meals out, to make them last longer. A drink of water to wash the food down, and he returned to the middle of the cage, where he proceeded to conduct a few intimate researches with his beak under his left wing. After which he mewed like a cat, and relapsed into silent meditation once more. He closed his eyes and pondered on his favorite problem—why was he a parrot? This was always good for an hour or so, and it was three o’clock before he had come to his customary decision that he didn’t know. Then, exhausted by brain work and feeling a trifle hipped by the silence of the room, he looked about him for some way of jazzing existence up a little. It occurred to him that if he barked again it might help.

“Woof-woof-woof!”

Good as far as it went, but it did not go far enough. It was not real excitement. Something rather more dashing seemed to him to be indicated. He hammered for a moment or two on the floor of his cage, ate a mouthful of the newspaper there, and stood with his head on one side, chewing thoughtfully. It didn’t taste as good as usual. He suspected Nelly of having changed his “Daily Mail” for the “Daily Express,” or something. He swallowed the piece of paper, and was struck by the thought that a little climbing exercise might be what his soul demanded. (You hang on by your beak and claws and work your way up to the roof. It sounds tame, but it’s something to do.) He tried it. And, as he gripped the door of the cage, it swung open. Bill, the parrot, now perceived that this was going to be one of those days. He had not had a bit of luck like this for months.

For a while he sat regarding the open door. Then, proceeding cautiously, he passed out into the room. He had been out there before, but always chaperoned by Nelly. This was something quite different. It was an adventure. He hopped on to the windowsill, and perceived suddenly that the world was larger than he had supposed. Apparently there was a lot of it outside the room. How long this had been going on, he did not know, but obviously it was a thing to be investigated. The window was open at the bottom, and just outside the window were what he took to be the bars of another and larger cage. As a matter of fact they were railings which ran the length of the house, and were much used by small boys as a means of rattling sticks. One of these stick-rattlers passed as Bill stood there looking down. The noise startled him for a moment. Then he seemed to come to the conclusion that this sort of thing was to be expected if you went out into the great world and that a parrot who intended to see life must not allow himself to be deterred by trifles. He crooned a little, and finally, stepping in a stately way over the windowsill with his toes turned in at right angles, caught at the top of the railing with his beak, and proceeded to lower himself. Arrived at the level of the street, he stood looking out.

A dog trotted up, spied him, and came up to sniff.

“Good-by, boy!” said Bill chattily.

The dog was taken aback. Hitherto, in his limited experience, birds had been birds and men men. Here was a blend of the two. What was to be done about it? He barked tentatively; then, finding that nothing disastrous ensued, pushed his nose between two of the bars and barked again. Anyone who knew Bill could have told him that he was asking for it, and he got it. Bill leaned forward and nipped his nose. The dog started back with a howl of agony. He was learning something new every minute.

“Woof-woof-woof!” said Bill sardonically.

He perceived trousered legs, four of them, and, cocking his eye upward, saw that two men stood before him. They were gazing down at him in the stolid manner peculiar to the proletariat of London in the presence of the unusual. For some minutes they stood drinking him in, then one of them gave judgment.

“It’s a parrot!” He removed a pipe from his mouth and pointed with the stem. “A perishin’ parrot, that is, Erb.”

“Ah!” said Erb, a man of few words.

“A parrot,” proceeded the other. He was seeing clearer into the matter every moment. “That’s a parrot, that is, Erb. My brother Joe’s wife’s sister ’ad one of ’em. Come from abroad, they do. My brother Joe’s wife’s sister ’ad one of ’em. Red-’aired gal she was. She ’ad one of ’em. Parrots they’re called.”

He bent down for a closer inspection, and inserted a finger through the railings. Erb abandoned his customary taciturnity and spoke words of warning.

“Tike care, ’e don’t sting yer, ’Enry!”

Henry seemed wounded.

“Woddyer mean, sting me? I know all abart parrots, I do. My brother Joe’s wife’s sister ’ad one of ’em. They don’t ’urt yer, not if you’re kind to ’em. You know yer pals when you see ’em, don’t yer, mate?” he went on, addressing Bill, who was contemplating the finger with one half-closed eye.

“Good-by, boy,” said the parrot, evading the point.

“J’ear that?” cried Henry delightedly. “ ‘Goo’-by, boy!’ ’Uman, they are!”

“ ’E’ll ’ave a piece out of yer finger,” warned Erb, the suspicious.

“Wot, ’im!” Henry’s voice was indignant. He seemed to think that his reputation as an expert on parrots had been challenged. “ ’E wouldn’t ’ave no piece out of my finger.”

“Bet yer a narf-pint ’e would ’ave a piece out of yer finger,” persisted the skeptic.

“No blinkin’ parrot’s goin’ to ’ave no piece out of no finger of mine! My brother Joe’s wife’s sister’s parrot never ’ad no piece out of no finger of mine!” He extended the finger further and waggled it enticingly beneath Bill’s beak. “Cheerio, matey!” he said winningly. “Polly want a nut?”

Whether it was mere indolence, or whether the advertised docility of that other parrot belonging to Henry’s brother’s wife’s sister had caused him to realize that there was a certain standard of good conduct for his species, one cannot say; but for a while Bill merely contemplated temptation with a detached eye.

“See!” said Henry.

“Woof-woof-woof!” said Bill.

“Wow-wow-wow!” yapped the dog, suddenly returning to the scene and going on with the argument at the point where he had left off.

The effect on Bill was catastrophic. His nerves were shocked, and, as always under such conditions, his impulse was to bite blindly. He bit, and Henry (one feels sorry for Henry; he was a well-meaning man) leaped back with a loud howl.

“That’ll be ’arf a pint,” said Erb, always the business man.

Henry removed his finger from his mouth. “Lend me the loan of that stick of yours, Erb!” he said tensely.

Erb silently yielded up the stout stick which was his inseparable companion. Henry, a vastly different man from the genial saunterer of a moment ago, poked wildly through the railings. Bill, panic-stricken now and wishing for nothing better than to be back in his cozy cage, shrieked loudly for help. And Freddie Rooke, rounding the corner with Jill, stopped dead and turned pale.

“Good God!” said Freddie.

§2

IN pursuance of his overnight promise to Derek, Freddie Rooke had telephoned to Jill immediately after breakfast, and had arranged to call at Ovington Square in the afternoon. Arrived there, he found Jill with a telegram in her hand. Her uncle Christopher, who had been enjoying a breath of sea air down at Brighton, was returning by an afternoon train, and Jill had suggested that Freddie should accompany her to Victoria, pick up Uncle Chris, and escort him home. Freddie, whose idea had been a tête-à-tête involving a brotherly lecture on impetuosity, had demurred but had given way in the end: and they had set out to walk to Victoria together. Their way had lain through Daubeny Street, and they turned the corner just as the brutal onslaught on the innocent Henry had occurred. Bill’s shrieks, which were of an appalling timbre, brought them to a halt.

“What is it?” cried Jill.

“It sounds like a murder!”

“Nonsense!”

“I don’t know, you know—this is the sort of street chappies are murdering people in all the time.”

They caught sight of the group in front of them, and were reassured. Nobody could possibly be looking so aloof and distrait as Erb, if there were a murder going on.

“It’s a bird!”

“It’s a jolly old parrot. See it? Just inside the railings.”

A red-hot wave of rage swept over Jill. Whatever her defects—and already this story has shown her far from perfect—she had the excellent quality of loving animals and blazing into fury when she saw them ill treated. At least three draymen were going about London with burning ears as the result of what she had said to them on discovering them abusing their patient horses. Zoologically Bill, the parrot, was not an animal, but he counted as one with Jill, and she sped down Daubeny Street. Freddie, spatted and hatted and trousered as became the man of fashion, followed disconsolately, ruefully aware that he did not look his best sprinting like that. But Jill was cutting out a warm pace, and he held his hat on with one neatly gloved hand and did what he could to keep up.

Jill reached the scene of battle, and, stopping, eyed Henry with a baleful glare. We, who have seen Henry in his calmer moments and know him for the good fellow he was, are aware that he was more sinned against than sinning. If there is any spirit of justice in us, we are pro-Henry. In his encounter with Bill, the parrot, Henry undoubtedly had right on his side. His friendly overtures, made in the best spirit of kindliness, had been repulsed. He had been severely bitten. And he had lost half a pint of beer to Erb. As impartial judges we have no other course before us than to wish Henry luck and bid him go to it. But Jill, who had not seen the opening stages of the affair, thought far otherwise. She merely saw in Henry a great brute of a man poking at a defenseless bird with a stick.

She turned to Freddie, who had come up at a gallop and was wondering why the deuce this sort of thing happened to him out of a city of six millions.

“Make him stop, Freddie!”

“Oh, I say!”

“Can’t you see he’s hurting the poor thing? Make him leave off! Brute!” she added to Henry (for whom one’s heart bleeds) as he jabbed once again at his adversary.

Freddie stepped reluctantly up to Henry, and tapped him on the shoulder. Freddie was one of those men who have a rooted idea that a conversation of this sort can only be begun by a tap on the shoulder.

“Look here, you know, you can’t do this sort of thing, you know!” said Freddie.

Henry raised a scarlet face.

“ ’Oo are you?” he demanded.

This attack from the rear, coming on top of his other troubles, tried his restraint sorely.

“Well—” Freddie hesitated. It seemed silly to offer the fellow one of his cards. “Well, as a matter of fact, my name’s Rooke—”

“And who,” pursued Henry, “arsked you to come shoving your ugly mug in ’ere?”

“Well, if you put it that way—”

“ ’E comes messing about,” said Henry complainingly, addressing the universe, “and interfering in what don’t concern ’im and mucking around and interfering and messing about— Why,” he broke off in a sudden burst of eloquence, “I could eat two of you for a relish wiv me tea, even if you ’ave got white spats!”

HERE Erb, who had contributed nothing to the conversation, remarked “Ah!” and expectorated on the sidewalk. The point, one gathers, seemed to Erb well taken. A neat thrust, was Erb’s verdict.

“Just because you’ve got white spats,” proceeded Henry, on whose sensitive mind these adjuncts of the costume of the well-dressed man about town seemed to have made a deep and unfavorable impression, “you think you can come mucking around and messing abart and interfering and mucking around! This bird’s bit me in the finger, and ’ere’s the finger, if you don’t believe me, and I’m going to twist ’is neck, if all the perishers with white spats in London come messing abart and mucking around, so you take them white spats of yours ’ome and give ’em to the old woman to cook for your Sunday dinner!”

And Henry, having cleansed his stuff’d bosom of that perilous stuff which weighs upon the heart, shoved the stick energetically once more through the railings.

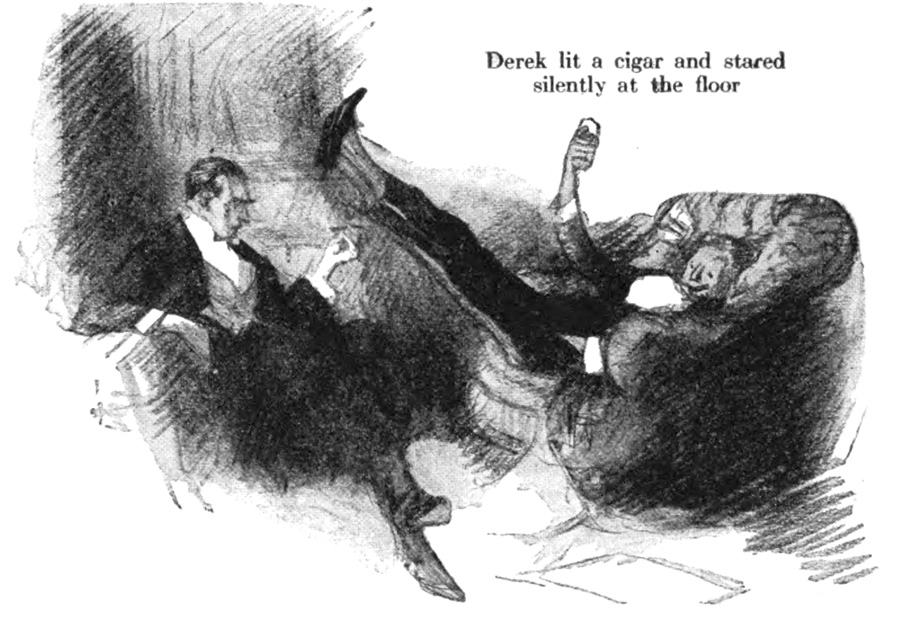

Jill darted forward. Always a girl who believed that if you want a thing well done you must do it yourself, she had applied to Freddie for assistance merely as a matter of form. All the time she had felt that Freddie was a broken reed, and such he had proved himself. Freddie’s policy in this affair was obviously to rely on the magic of speech, and any magic his speech might have had was manifestly offset by the fact that he was wearing white spats. Jill seized the stick and wrenched it out of Henry’s hand.

“Woof-woof-woof!” said the parrot.

No dispassionate auditor could have failed to detect the nasty ring of sarcasm. It stung Henry. He was not normally a man who believed in violence to the gentler sex outside a clump on the head of his missus when the occasion seemed to demand it; but now he threw away the guiding principles of a lifetime and turned on Jill like a tiger.

“Gimme that stick!”

“Get back!”

“Here, I say, you know!” said Freddie.

HENRY, now thoroughly overwrought, made a lunge at Jill; and Jill, who had a straight eye, hit him accurately on the side of the head.

“Goo!” said Henry, and sat down.

And then from behind Jill a voice spoke: “What’s all this?”

A stout policeman had manifested himself from empty space.

“This won’t do!” said the policeman.

Erb, who had been a silent spectator of the fray, burst into speech.

“She ’it ’im!”

The policeman looked at Jill. “Your name, please, and address, miss?” he said.

A girl in blue with a big hat had come up, and was standing staring open-mouthed at the group. At the sight of her, Bill the parrot uttered a shriek of welcome. Nelly Bryant had returned, and everything would now be all right again.

“Mariner,” said Jill, pale and bright-eyed. “I live at No. 22, Ovington Square.”

“And yours, sir?”

“Mine? Oh, ah, yes. I see what you mean. Rooke, you know. F. L. Rooke. I live at the Albany, and all that sort of thing.”

The policeman made an entry in his notebook.

“Officer,” cried Jill, “this man was trying to kill that parrot and I stopped him—”

“Can’t help that, miss. You ’adn’t no right to ’it a man with a stick. You’ll ’ave to come along.”

“But, I say, you know!” Freddie was appalled. This sort of thing had happened to him before, but only on Boat-Race Night at the Empire, where it was expected of a chappie. “I mean to say!”

“And you too, sir. You’re both in it.”

“But—”

“Oh, come along, Freddie,” said Jill quietly. “It’s perfectly absurd, but it’s no use making a fuss.”

“That,” said the policeman cordially, “is the right spirit!”

§3

LADY UNDERHILL paused for breath. She and Derek were sitting in Freddie Rooke’s apartment at the Albany, and the subject of her monologue was Jill. Derek had been expecting the attack, and had wondered why it had not come before. All through supper on the previous night, even after the discovery that Jill was supping at a near-by table with a man who was a stranger to her son, Lady Underhill had preserved a grim reticence with regard to her future daughter-in-law. But to-day she had spoken her mind with all the energy which comes of suppression. She had relieved herself with a flow of words of all the pent-up hostility that had been growing within her since that first meeting in this same room. She had talked rapidly, for she was talking against time. The Town Council of the principal city in Derek’s constituency had decided on to-morrow morning for laying the foundation stone of their new Town Hall, and Derek was to preside at the celebrations. Already Parker had been dispatched to telephone for a cab to take him to the station, and at any moment their conversation might be interrupted. So Lady Underhill made the most of what little time she had.

Derek had listened gloomily, scarcely rousing himself to reply. His mother would have been gratified could she have known how powerfully her arguments were working upon him. That little imp of doubt which had vexed him in the cab as he drove home from Ovington Square had not died in the night. It had grown and waxed more formidable. And now, aided by this ally from without, it had become a colossus, straddling his soul. Derek looked frequently at the clock and cursed the unknown cabman whose delay was prolonging the scene. Something told him that only flight could serve him now. He never had been able to withstand his mother in one of her militant moods. She seemed to numb his faculties. Other members of his family had also noted this quality in her.

LADY UNDERHILL, having said all she had to say, recovered her breath and began to say it again.

“You must be mad, Derek, to dream of handicapping yourself at this vital stage of your career with a wife who not only will not be a help to you, but must actually be a ruinous handicap. I am not blaming you for imagining yourself in love in the first place, though I really should have thought that a man of your strength and character would— However, as I say, I am not blaming you for that. Superficially, no doubt, this girl might be called attractive. I do not admire the type myself, but I suppose she has that quality—in my time we should have called it boldness—which seems to appeal to the young men of to-day. I could imagine her fascinating a weak-minded imbecile like your friend Mr. Rooke. But that you— Still, there is no need to go into that. What I am trying to point out is that in your position, with a career like yours in front of you, it’s quite certain that in a year or two you will be offered some really big and responsible position; you would be insane to tie yourself to a girl who seems to have been allowed to run perfectly wild, whose uncle is a swindler. . . .”

“She can’t be blamed for her uncle.”

“. . . Who sups alone with strange men in public restaurants . . .”

“I explained that.”

“You may have explained it. You certainly did not excuse it or make it a whit less outrageous. You cannot pretend that you really imagine that an engaged girl is behaving with perfect correctness when she allows a man she has only just met to take her to supper at the Savoy, even if she did know him slightly years and years ago. It is very idyllic to suppose that a childhood acquaintance excuses every breach of decorum; but I was brought up to believe otherwise. I don’t wish to be vulgar, but what it amounts to is that this girl was having supper—supper! in my days girls were in bed at supper time—with a strange man who picked her up at a theatre!”

Derek shifted uneasily. There was a part of his mind which called upon him to rise up and challenge the outrageous phrase and demand that it be taken back. But he remained silent. The imp colossus was too strong for him. She is quite right, said the imp—that is an unpleasant but accurate description of what happened. He looked at the clock again and wished for the hundredth time that the cab would come. Jill’s photograph smiled at him from beside the clock. He looked away, for, when he found his eyes upon it, he had an odd sensation of baseness, as if he were playing some one false who loved and trusted him.

A gleam came into Lady Underhill’s black eyes. All her life she had been a fighter, and experience had taught her to perceive when she was winning. She blessed the dilatory cabman.

“Well, I am not going to say any more,” she said, getting up and buttoning her glove. “I will leave you to think it over. All I will say is that, though I only met her yesterday, I can assure you that I am quite confident that this girl is just the sort of harum-scarum, so-called ‘modern’ girl who is sure some day to involve herself in a really serious scandal. I don’t want her to be in a position to drag you into it as well. Yes, Parker, what is it? Is Sir Derek’s cab here?”

THE lantern-jawed Parker had entered softly and was standing deferentially in the doorway. There was no emotion on his face beyond the vague sadness which a sense of what was correct made him always wear like a sort of mask when in the presence of those of superior station.

“The cab will be at the door very shortly, m’lady. If you please, Sir Derek, a policeman has come with a message, and I understand from him that Mr. Rooke and Miss Mariner have been arrested.”

“Arrested! What are you talking about?”

“Mr. Rooke desired the officer to ask you to be good enough to step round and bail them out!”

The gleam in Lady Underhill’s eye became a flame, but she controlled her voice. “Why were Miss Mariner and Mr. Rooke arrested, Parker?”

“As far as I can gather, m’lady, Miss Mariner struck a man in the street with a stick, and they took both her and Mr. Rooke to the Chelsea Police Station.”

Lady Underhill glanced at Derek, who was looking into the fire.

“This is a little awkward, Derek,” she said suavely. “If you go to the police station, you will miss your train.”

“I fancy, m’lady, it would be sufficient if Sir Derek were to dispatch me with a check for ten pounds.”

“Very well. Tell the policeman to wait a moment.”

“Very good, m’lady.”

Derek roused himself with an effort. His face was drawn and gloomy. He sat down at the writing table and took out his check book. There was silence for a moment, broken only by the scratching of the pen. Parker took the check and left the room.

“Now, perhaps,” said Lady Underhill, “you will admit that I was right!” She spoke in almost an awed voice, for this occurrence at just this moment seemed to her very like a direct answer to prayer. “You can’t hesitate now! You must free yourself from this detestable entanglement!”

Derek rose without speaking. He took his coat and hat.

“Derek! You will! Say you will!”

Derek put on his coat.

“Derek!”

“For Heaven’s sake, leave me alone, mother. I want to think.”

“Very well. I will leave you to think it over, then.” Lady Underhill moved to the door. At the door she paused for a moment, and seemed about to speak again, but her mouth closed resolutely. She was a shrewd woman, and knew that the art of life is to know when to stop talking.

“Good-by.”

“Good-by, mother.”

“I’ll see you when you get back?”

“Yes. No. I don’t know. I’m not certain when I shall return. I may go away for a bit.”

The door closed behind Lady Underhill. Derek sat down again at the writing table. He wrote a few words on a sheet of paper, then tore it up. His eye traveled to the mantelpiece. Jill’s photograph smiled happily down at him. He turned back to the writing table, took out a fresh piece of paper, thought for a few moments, and began to write again.

The door opened softly. “The cab is at the door, Sir Derek,” said Parker.

Derek addressed an envelope and got up. “All right. Thanks. Oh, Parker, stop at a district messenger office on your way to the police station and have this sent off at once.”

“Very good, Sir Derek,” said Parker.

Derek’s eyes turned once more to the mantelpiece. He stood looking for an instant, then walked quickly out of the room.

Editor’s note:

Printer’s errors corrected above:

Magazine had “Gimme me that stick!” in §2 of ch. V; extraneous “me” removed.

Magazine had ? after “must actually be a ruinous handicap” in §3 of ch. V; corrected to full stop as in both book versions.

Madame Eulalie’s Rare Plums

Madame Eulalie’s Rare Plums