Cosmopolitan, August 1920

IT was Parker, Mr. Brewster’s English valet, who first directed Archie’s attention to the hidden merits of Pongo. Archie had visited his father-in-law’s suite one morning—not absolutely with the definite purpose of making a touch, but rather with the nebulous notion of getting into his relative’s ribs for a few dollars if the latter seemed to be sufficiently cheery and full of the milk of human kindness—and he had found the sitting-room occupied only by the valet, who was dusting the furniture and bric-à-brac. After a courteous exchange of greetings, Archie sat down and lighted a cigarette. Parker went on dusting.

“The guv’nor,” said Parker, breaking the silence, “ ’as some nice little objay d’ar, sir.”

“Little what?”

“Objay d’ar, sir.”

“Of course, yes.” Light dawned upon Archie. “French for junk. I know what you mean now. Dare say you’re right, old friend. Don’t know much about these things myself.”

Parker gave an appreciative flick at a vase on the mantelpiece. His encomium had been quite justified. One of the things which made the Hotel Cosmopolis different from other New York hotels was the fact that its proprietor had an educated taste in matters of art. Archie’s taste in art was not precious, and he found a difficulty in looking civilly at most of his father-in-law’s belongings.

Parker had picked up a small china figure. It was of very delicate workmanship, and represented a warrior of pre-khaki days advancing with a spear upon some adversary who, judging from the contented expression on the warrior’s face, was smaller than himself. Parker regarded this figure with a look of affectionate admiration which seemed to Archie absolutely uncalled-for.

“Very valuable, some of the gov’nor’s things,” said Parker. “This one, now. Worth a lot of money. Oh, a lot of money!”

“Very valuable, some of the gov’nor’s things,” said Parker. “This one, now. Worth a lot of money. Oh, a lot of money!”

“What—Pongo?” said Archie incredulously.

“Sir?”

“I always call that rummy-looking little what-not ‘Pongo.’ Don’t know what else you could call him—what?”

The valet seemed to disapprove of this levity. He shook his head and replaced the figure on the mantelpiece.

“Worth a lot of money,” he repeated. “Not by itself, no.”

“Oh, not by itself?”

“No, sir. Things like this come in pairs. Somewhere or other there’s the companion-piece to this ’ere, and if the gov’nor could get ’old of it, he’d ’ave something worth ’aving. But one’s no good without the other. You ’ave to ’ave both, if you understand my meaning, sir.”

“I see. Like filling a straight flush—what?”

“Precisely, sir.”

Archie gazed at Pongo again, with the dim hope of discovering virtues not immediately apparent to the casual observer. But without success. Pongo left him cold—even chilly. He would not have taken Pongo as a gift to oblige a dying friend.

“How much would the pair be worth?” he asked. “Ten dollars?”

Parker smiled a gravely superior smile.

“A leetle more than that, sir. Several thousand dollars, more like it.”

“Do you mean to say,” said Archie, with honest amazement, “that there are chumps going about loose—absolutely loose—who would pay that for a weird little object like Pongo?”

“Undoubtedly, sir. These antique china figures are in great demand among collectors.”

Archie looked at Pongo once more and shook his head.

“Well, well, well! It takes all sorts to make a world—what?”

What might be called the revival of Pongo, the restoration of Pongo to the ranks of the things that matter, took place several weeks later, when Archie was making holiday at the house which his father-in-law had taken for the summer at Brookport on the south shore of Long Island. The curtain of the second act may be said to rise on Archie strolling back from the golf-links in the cool of an August evening.

It was, to coin a phrase, the end of a perfect day. The setting sun fell pleasantly on the waters of the Great South Bay. A gentle breeze was blowing in off Fire Island. Crickets chirped unceasingly in the meadows, and birds sang their evening hymn in the trees. The peace of it all had induced in Archie a mood of tranquil happiness which nothing could disturb. From time to time he sang lightly, and wondered idly if Lucille, his wife, would put the finishing touch upon the all-rightness of everything by coming to meet him and sharing his homeward walk.

She came in view at this moment, a trim little figure in a white skirt and a pale-blue sweater. She waved to Archie, and Archie, as always at the sight of her, was conscious of that jumpy, fluttering sensation about the heart which, translated into words, would have formed the question: “What on earth could have made a girl like that fall in love with a chump like me?” It was a question which he was continually asking himself, and one which was perpetually in the mind also of Mr. Brewster, his father-in-law. The matter of Archie’s unworthiness to be the husband of Lucille was practically the only one on which the two men saw eye to eye.

“Hullo-ullo-ullo!” said Archie. “Here we are—what? I was just hoping you would drift over the horizon.”

Lucille kissed him.

“You’re a darling,” she said. “And where is father? Why didn’t he come back with you?”

“Well, as a matter of fact, he didn’t seem any too keen on my company. I left him in the locker-room, chewing a cigar. Gave me the impression of having something on his mind.”

“Oh, Archie, you didn’t beat him again?”

Archie looked uncomfortable.

“Well, as a matter of fact, old thing, to be absolutely frank, I, as it were, did.”

“Not badly?”

“Well, yes. I rather fancy I put it across him with some vim and not a little emphasis. I tooled him in nine down.”

“But you promised me you would let him beat you to-day. You know how pleased it would have made him.”

“I know. But, light of my soul, have you any idea how dashed difficult it is to be beaten by your festive parent at golf?”

“Oh, well”—Lucille sighed—“it can’t be helped, I suppose. But I do wish we could think of some way of making father fonder of you.”

“So do I. But what’s one to do? I smile winsomely at him and what-not, but he doesn’t respond.”

“Well, we shall have to try to think of something. I want him to realize what an angel you are.” Lucille felt in the pocket of her sweater. “Oh, there’s a letter for you. I’ve just been to fetch the mail. I don’t know who it can be from.”

Archie inspected the envelop. It provided no solution.

“That’s rummy! Who could be writing to me?”

“Open it and see.”

“Dashed bright scheme! I will. Herbert Parker. Who the deuce is Herbert Parker?”

“Parker? Father’s valet’s name was Parker.”

“And still is, no doubt—what? Do you mean the long, thin bird—the one he fired just before we came down here?”

“Yes. Father found he was wearing his shirts. But read the letter. I expect he wants you to use your influence with father to have him taken back.”

“My influence? With your father? Well, I’m dashed! Sanguine sort of johnny, if he does! Well, here’s what he says:

“Dear Sir:

“It is some time since the undersigned had the honor of conversing with you, but I am respectfully trusting that you may recall me to mind when I mention that until recently I served Mr. Brewster, your father-in-law, in the capacity of valet. Owing to an unfortunate misunderstanding, I was dismissed from that position and am now temporarily out of a job. ‘How art thou fallen from heaven, O Lucifer, son of the morning!’ (Isaiah, xiv. 12)——

“You know,” said Archie admiringly, “this bird is hot stuff. I mean to say he writes dashed well.”

“I always thought Parker was a very clever man. Father used to say he knew as much about antiques and things as he did himself.”

“ ‘Antiques!’ I knew there was something at the back of the old bean. All along I’ve been trying to remember just how and when it was that friend Parker and I became the good old college chums he seems to think we are. We had a long and animated conversation one morning in your father’s suite. He told me something dashed interesting, I recollect. I can’t recall what it was, but I know it struck me as dashed interesting. Well, let’s get on with it.

“It is not, however, with my own affairs that I desire to trouble you, dear sir. I have little doubt that all will be well with me and that I shall not fall like a sparrow to the ground. ‘I have been young, and now am old; yet have I not seen the righteous forsaken, nor his seed begging bread.’ (Psalms, xxxvii. 25.) My object in writing to you is as follows: You may recall that I had the pleasure of meeting you one morning in Mr. Brewster’s suite, when we had an interesting talk on the subject of Mr. B.’s objets d’art. You may recall being particularly interested in a small china figure. I informed you, if you remember, that, could the accompanying figure be secured, the pair would be extremely valuable.

“I am glad to say, dear sir, that this has now transpired, and is on view at Beale’s Art Galleries on West Forty-fifth Street, where it will be sold to-morrow at auction, the sale commencing at two-thirty sharp. If Mr. Brewster cares to attend, he will, I fancy, have little trouble in securing it at a reasonable price. I confess that I had thought of refraining from apprizing my late employer of this matter, but more Christian feelings have prevailed. ‘If thine enemy hunger, feed him; if he thirst, give him drink; for in so doing thou shalt heap coals of fire on his head.’ (Romans, xii. 20.) Nor, I must confess, am I altogether uninfluenced by the thought that my action in this matter may conceivably lead to Mr. B. consenting to forget the past and to reinstate me in my former position. However, I am confident that I can leave this to his good feeling. I remain,

“Respectfully yours,

“Herbert Parker.”

Lucille clapped her hands.

“How splendid! Father will be pleased!”

“Yes. Friend Parker has certainly found a way to make the old lad fond of him. Wish I could!”

“But you can, silly! He’ll be delighted when you show him that letter.”

“Yes, with Parker. Old Herb Parker’s is the neck he’ll fall on—not mine.”

Lucille reflected.

“Oh, Archie darling, I’ve got an idea!”

“Decant it.”

“Why don’t you slip up to New York to-morrow and buy the thing and give it to father as a surprise?”

Archie patted her hand kindly. He hated to spoil her girlish day-dreams.

“Yes,” he said. “But reflect, queen of my heart! I have at the moment of going to press just two dollars twenty-five in specie, which I took off your father this afternoon. We were playing a quarter a hole. He coughed it up without enthusiasm; but I’ve got it. And that’s all I have got.”

“That’s all right. You can pawn that ring and that bracelet of mine.”

“Oh, I say—what? Hock the family jewels?”

“Only for a day or two. Of course, once you’ve got the thing, father will pay us back. He would give you all the money we asked him for, if he knew what it was for. But I want to surprise him. And if you were to go to him and ask him for a thousand dollars without telling him what it was for, he might refuse.”

“He might,” said Archie. “He might.”

“It all works out splendidly. To-morrow’s the Invitation Handicap, and father’d hate to have to go up to town himself and not play in it. But you can slip up and slip back without his knowing anything about it.”

“It sounds a ripe scheme,” Archie pondered. “Yes; it has all the earmarks of a somewhat fruity wheeze. By Jove, it is a fruity wheeze! It’s an egg!”

“ ‘An egg?’ ”

“Good egg, you know— Hullo, here’s a postscript. I didn’t see it.

“P. S. I should be glad if you would convey my most cordial respects to Mrs. Moffam. Will you also inform her that I chanced to meet Mr. William this morning on Broadway, just off the boat? He desired me to send his regards and to say that he would be joining you at Brookport in the course of a day or so. Mr. B. will be pleased to have him back. ‘A wise son maketh a glad father.’ (Proverbs, x. 1.)”

“Who’s Mr. William?” asked Archie.

“My brother Bill, of course. I’ve told you all about him.”

“Oh, yes, of course. Your brother Bill. Rummy to think I’ve got a brother-in-law I’ve never seen.”

“You see, we married so suddenly. When we married, Bill was in Yale. Then he went over to Europe for a trip to broaden his mind. You must look him up to-morrow when you get back to New York. He’s sure to be at his club.”

“I’ll make a point of it. Well, vote of thanks to jolly old Parker! This really does begin to look like the point in my career where I start to have your forbidding old parent eating out of my hand.”

“Yes; it’s an egg, isn’t it?”

“It’s an omelet!” said Archie enthusiastically.

The business negotiations in connection with the bracelet and the ring occupied Archie on his arrival in New York to an extent which made it impossible for him to call on brother Bill before lunch, and the fact that his friend Reggie van Tuyl happened to join him at the table prolonged lunch till a few minutes before the time scheduled for the opening of the sale. Archie decided to postpone the affecting meeting of brothers-in-law to a more convenient season.

“I say, Reggie, old top,” he said, confiding in his friend, “do you know anything about sales?”

“ ‘Sales?’ ”

“Auction sales, don’t you know.”

Reginald considered.

“Well, they’re sales, you know. Auction sales, you understand.”

Archie sought further enlightenment.

“Yes; but what’s the jolly old procedure? I mean, what do I do? I’ve got to buy something at Beale’s this afternoon. How do I set about it?”

“Well,” said Reggie drowsily, “there are several ways of bidding, you know. You can shout, or you can nod, or you can twiddle your fingers—I’ll tell you what. I’ve nothing to do this afternoon. I’ll come with you and show you.”

When he entered the art galleries a few minutes later, Archie was glad of the moral support of even such a wobbly reed as Reggie van Tuyl. There is something about an auction-room which weighs heavily upon the novice. The hushed interior was bathed in a dim, religious light, and the congregation, seated on small wooden chairs, gazed in reverent silence at the pulpit, where a gentleman of commanding presence and sparkling pince-nez was delivering a species of chant. Behind a gold curtain at the end of the room, mysterious forms flitted to and fro. Archie found the atmosphere oppressively ecclesiastical. He sat down and looked about him. The presiding priest went on with his chant:

“Sixteen-sixteen-sixteen-sixteen-sixteen—worth three hundred—sixteen-sixteen-sixteen-sixteen-sixteen—ought to bring five hundred—sixteen-sixteen-seventeen-seventeen-eighteen-eighteen-nineteen-nineteen-nineteen.” He stopped and eyed the worshipers with a glittering and reproachful eye. They had, it seemed, disappointed him. His lips curled, and he waved a hand toward a grimly uncomfortable-looking chair with insecure legs and a good deal of gold paint about it. “Gentlemen! Ladies and gentlemen! You are not here to waste my time; I am not here to waste yours. Am I seriously offered nineteen dollars for this eighteenth-century chair, acknowledged to be the finest piece sold in New York for months and months? Am I—twenty? I thank you. Twenty-twenty-twenty-twenty. Your opportunity! Priceless! Very few extant. Twenty-five-five-five-thirty-thirty-thirty. Just what you are looking for. The only one in the city of New York. Thirty-five-five-five-five. Forty-forty-forty-forty-forty. Look at those legs! Back it into the light, Willie. Let the light fall on those legs!”

Willie, a sort of acolyte, maneuvered the chair as directed. Reggie van Tuyl showed his first flicker of interest.

“Willie,” he observed, eying that youth more with pity than reproach, “has a face like Jo-Jo, the dog-faced boy—don’t you think so?”

Archie nodded briefly.

“Forty-five-five-five-five-five,” chanted the high priest. “Once forty-five. Twice forty-five. Third and last call, forty-five. Sold at forty-five. Gentleman in the fifth row.”

Archie looked up and down the row with a keen eye. He was anxious to see who had been chump enough to give forty-five dollars for such a frightful object. He became aware of the dog-faced Willie leaning toward him.

“Name, please?” said the canine one.

“Eh, what?” said Archie. “Oh, my name’s Moffam, don’t you know.” The eyes of the multitude made him feel a little nervous. “Er—glad to meet you and all that sort of rot.”

“Ten dollars deposit, please,” said Willie.

“I don’t absolutely follow you, old bean. What is the big thought at the back of all this?”

“Ten dollars deposit on the chair.”

“What chair?”

“You bid forty-five dollars for the chair.”

“Me?”

“You nodded,” said Willie accusingly. “If,” he went on, reasoning closely, “you didn’t want to bid, why did you nod?”

Archie was embarrassed. He could, of course, have pointed out that he had merely nodded in adhesion to the statement that the other had a face like Jo-Jo, the dog-faced boy; but something seemed to tell him that a purist might consider the excuse deficient in tact. He hesitated a moment, then handed over a ten-dollar bill, the price of Willie’s feelings. Willie withdrew like a tiger slinking from the body of its victim.

“I say, old thing,” said Archie to Reggie, “this is a bit thick, you know. No purse will stand this strain.”

Reggie considered the matter. His face seemed drawn under the mental strain.

“Don’t nod again,” he advised. “If you aren’t careful, you get into the habit of it. When you want to bid, just twiddle your fingers. Yes; that’s the thing—twiddle.”

He sighed drowsily. The atmosphere of the auction-room was close; you weren’t allowed to smoke, and altogether he was beginning to regret that he had come. The service continued. Objects of varying unattractiveness came and went, eulogized by the officiating priest but coldly received by the congregation.

“If your thing—your whatever-it-is doesn’t come up soon, Archie,” said Reggie, fighting off with an effort the mists of sleep, “I rather think I shall be toddling along. What was it you came to get?”

“It’s rather difficult to describe. It’s a rummy-looking sort of what-not, made of china or something. I call it ‘Pongo’. At least, this one isn’t Pongo, don’t you know—it’s his little brother, but presumably equally foul in every respect. It’s all rather complicated, I know, but— Hullo!” He pointed excitedly. “By Jove! We’re off! There it is! Look! Willie’s unleashing it now.”

Willie, who had disappeared through the gold curtain, had now returned, and was placing on a pedestal a small china figure of delicate workmanship. It was the figure of a warrior in a suit of armor, advancing with raised spear upon an adversary. A thrill permeated Archie’s frame. Parker had not been mistaken. This was undoubtedly the companion-figure to the redoubtable Pongo.

The high priest regarded the figure with a gloating enthusiasm wholly unshared by the congregation, who were plainly looking upon Pongo’s little brother as just another of those things.

“This,” he said, with a shake in his voice, “is something very special. China figure, said to date back to the Ming Dynasty. Unique. Nothing like it on either side of the Atlantic. If I were selling this at Christie’s, in London, where people,” he said nastily, “have an educated appreciation of the beautiful, the rare, and the exquisite, I should start the bidding at a thousand dollars. This afternoon’s experience has taught me that that might possibly be too high. Will anyone offer me a dollar for this unique figure?”

“Leap at it, old top!” said Reggie van Tuyl. “Twiddle, dear boy; twiddle! A dollar’s reasonable.”

Archie twiddled.

“One dollar I am offered,” said the high priest bitterly. “One gentleman here is not afraid to take a chance. One gentleman here knows a good thing when he sees one.” He abandoned the gently sarcastic manner for one of crisp and direct reproach. “Come, come, gentlemen; we are not here to waste time. Will anyone offer me one hundred dollars for this superb piece of—” He broke off, stared at some one in one of the seats in front of Archie. “Thank you,” he said, with a sort of gulp. “One hundred dollars I am offered. One hundred-one hundred-one hundred——”

Archie was startled. This sudden, tremendous jump, this wholly unforseen boom in Pongos, if one might so describe it, was more than a little disturbing. He could not see who his rival was, but it was evident that at least one among those present did not intend to allow Pongo’s brother to slip by without a fight. He looked helplessly at Reggie for counsel, but Reggie had now definitely given up the struggle. He was leaning back with closed eyes, breathing softly through his nose. Thrown on his own resources, Archie could think of no better course than to twiddle his fingers again. He did so, and the high priest’s chant took on a note of positive exuberance.

“Two hundred I am offered. Much better! Turn the pedestal round, Willie, and let them look at it. Slowly. Slowly. You aren’t spinning a roulette-wheel. Two hundred. Two-two-two-two-two.”

Archie’s concern increased. He seemed to be twiddling at this voluble man across seas of misunderstanding. Nothing is harder to interpret to a nicety than a twiddle, and Archie’s idea of the language of twiddles and the high priest’s idea did not coincide by a mile. The high priest appeared to consider that, when Archie twiddled, it was his intention to bid in hundreds, whereas, in fact Archie had meant to signify that he raised the previous bid by just one dollar. Archie felt that, if given time, he could make this clear to the high priest, but the latter gave him no time.

“Two hundred-two hundred-two-three-thank you, sir-three-three-three-four-four-five-five-six-six-seven-seven-seven——”

Archie sat limply in his wooden chair. One fact was clear to him: he must secure the prize. Lucille had sent him to New York expressly to do so. She had sacrificed her jewelry for the cause. She relied on him. The enterprise had become for Archie something almost sacred.

He twiddled again. The ring and the bracelet had fetched nearly twelve hundred dollars. Up to that figure, his hat was in the ring.

“Eight hundred I am offered. Eight hundred. Eight-eight-eight-eight——”

A voice spoke from somewhere at the back of the room. A quiet, cold, nasty, determined voice.

“Nine.”

Archie rose from his seat and spun round. This mean attack from the rear stung his fighting spirit. As he rose, a young man sitting immediately in front of him rose, too, and stared likewise. He was a square-built, resolute-looking young man, who reminded Archie vaguely of somebody he had seen before. But Archie was too busy trying to locate the man at the back to pay much attention to him. He detected him at last, owing to the fact that the eyes of everybody in that part of the room were fixed upon him. He was a small man of middle-age, with tortoise-shell-rimmed spectacles. He might have been a professor or something of the kind. Whatever he was, he was obviously a man to be reckoned with. He had a rich sort of look, and his demeanor was the demeanor of a man who is prepared to fight it out on these lines if it takes all summer.

“Nine hundred I am offered. Nine-nine-nine-nine——”

Archie glared defiantly at the spectacled man.

“A thousand!” he cried.

The irruption of high finance into the placid course of the afternoon’s proceedings had stirred the congregation out of its lethargy. There were excited murmurs. Necks were craned. Feet shuffled. As for the high priest, his cheerfulness was now more than restored, and his faith in his fellow man had soared from the depths to a very lofty altitude. He beamed with approval. Despite the warmth of his praise, he would have been quite satisfied to see Pongo’s little brother go at twenty dollars, and the reflection that the bidding had already reached one thousand and that his commission was twenty per cent. had engendered a mood of sunny happiness.

“One thousand is bid,” he caroled. “Now, gentlemen, I don’t want to hurry you over this. You are all connoisseurs here, and you don’t want to see a priceless china figure of the Ming Dynasty get away from you at a sacrifice price. Perhaps you can’t all see the figure where it is. Willie, take it round and show it to ’em. We’ll take a little intermission while you look carefully at this wonderful figure. Get a move on, Willie!”

Archie, sitting dazedly, was aware that Reggie van Tuyl had finished his beauty-sleep and was addressing the young man in the seat in front.

“Why, hullo!” said Reggie. “I didn’t know you were back. You remember me, don’t you? Reggie van Tuyl. I know your sister very well. Archie, old man, I want you to meet my friend, Bill Brewster. Why, dash it”—he chuckled sleepily—“I was forgetting. Of course! He’s your——”

“How are you?” said the young man. “Talking of my sister,” he said to Reggie, “I suppose you haven’t met her husband by any chance? I suppose you know she married some awful chump?”

“Me,” said Archie.

“How’s that?”

“I married your sister. My name’s Moffam.”

The young man seemed a trifle taken aback.

“Sorry,” he said.

“Not at all,” said Archie.

“I was only going by what my father said in his letters,” he explained in extenuation.

Archie nodded.

“I’m afraid your jolly old father doesn’t appreciate me. But I’m hoping for the best. If I can rope in that rummy-looking little china thing that Jo-Jo, the dog-faced boy, is showing the customers, he will be all over me. I mean to say, you know, he’s got another like it, and if he can get a full house, as it were, I’m given to understand he’ll be bucked, cheered, and even braced.”

The young man started.

“Are you the fellow who’s been bidding against me?”

“Eh, what? Were you bidding against me?”

“I wanted to buy the thing for my father. I’ve a special reason for wanting to get in right with him just now. Are you buying it for him, too?”

“Absolutely. As a surprise. It was Lucille’s idea. His valet, a chappie named Parker, tipped us off that the thing was to be sold.”

“ ‘Parker?’ Great Scott! It was Parker who tipped me off. I met him on Broadway, and he told me about it.”

“Rummy he never mentioned it in his letter to me. Why, dash it, we could have got the thing for about two dollars if we had pooled our bids.”

“Well, we’d better pool them now, and extinguish that pill at the back there. I can’t go above eleven hundred. That’s all I’ve got.”

“I can’t go above eleven hundred myself.”

“There’s just one thing: I wish you’d let me be the one to hand the thing over to father. I’ve a special reason for wanting to make a hit with him.”

“Absolutely!” said Archie magnanimously. “It’s all the same to me. I only wanted to get him generally braced, as it were, if you know what I mean.”

“That’s awfully good of you.”

“Not a bit, laddie, no, no—and far from it. Only too glad.”

Willie had returned from his rambles among the connoisseurs, and Pongo’s brother was back on his pedestal. The high priest cleared his throat and resumed his discourse.

“Now that you have all seen this superb figure, unique in the civilized world, we will—I was offered one thousand. One thousand-one-one-one-one. Eleven hundred? Thank you, sir. Eleven hundred I am offered.”

The high priest was now exuberant. You could see him doing figures in his head.

“You do the bidding,” said brother Bill.

“Right-o!” said Archie.

He waved a defiant hand.

“Thirteen,” said the man at the back.

“Fourteen, dash it!”

“Fifteen!”

“Sixteen!”

“Seventeen!”

“Eighteen!”

“Nineteen!”

“Two thousand!”

The high priest did everything but sing. He radiated goodwill and bonhomie.

“Two thousand I am offered. Is there any advance on two thousand? Come, gentlemen; I don’t want to give this superb figure away. Twenty-one hundred. Twenty-one-one-one-one. This is more the sort of thing I have been accustomed to. Twenty-two-two-two-two-two. Three-three-three. Twenty-three-three-three. Twenty-three hundred dollars I am offered.”

He gazed expectantly at Archie, as a man gazes at some favorite dog whom he calls upon to perform a trick. But Archie had reached the end of his tether. The hand that had twiddled so often and so bravely lay inert beside his trouser leg, twitching feebly. Archie was through.

“Twenty-three hundred,” said the high priest ingratiatingly.

Archie made no movement. There was a tense pause. The high priest gave a little sigh, like one waking from a beautiful dream.

“Twenty-three hundred,” he said. “Once twenty-three. Twice twenty-three. Third, last, and final call, twenty-three. Sold at twenty-three hundred. I congratulate you, sir, on a genuine bargain.”

Reggie van Tuyl had dozed off again. Archie tapped his brother-in-law on the shoulder.

“May as well be popping—what?”

They threaded their way sadly together through the crowd and made for the street. They passed into Fifth Avenue without breaking the silence.

“Bally nuisance!” said Archie at last.

“Rotten!”

“Wonder who that chappie was.”

“Some collector probably.”

“Well, it can’t be helped,” said Archie.

Brother Bill attached himself to Archie’s arm and became communicative.

“I didn’t want to mention it in front of van Tuyl,” he said, “because he’s such a talking machine. But you’re one of the family, and you can keep a secret.”

“Absolutely! Silent tomb and what-not.”

“The reason I wanted that darned thing was because I’ve just got engaged to a girl over in England, and I thought that, if I could hand my father that china-figure thing with one hand and break the news with the other, it might help a bit. She’s the most wonderful girl!”

“I’ll bet she is!” said Archie cordially.

“The trouble is she’s in the chorus of one of the revues over there, and father is apt to kick. So I thought— Oh, well, it’s no good worrying now. Come along, and I’ll tell you all about her.”

“That’ll be jolly!” said Archie.

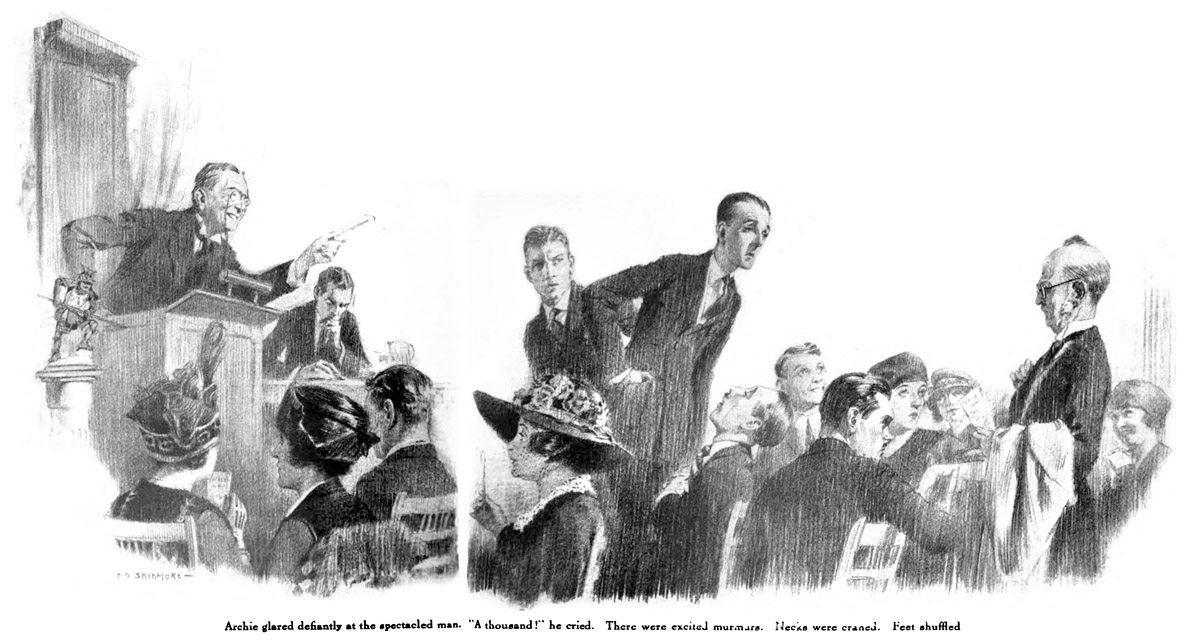

Archie reclaimed the family jewelry from its temporary home next morning. Then, feeling ripe for luncheon, he sauntered back to the Cosmopolis. On entering the lobby, he was surprised to see his father-in-law. More surprising still, Mr. Brewster seemed to be in jovial mood and even tolerably pleased to see his son-in-law.

“Hullo-ullo!” said Archie. “I thought you were at Brookport.”

“I came up this morning, to meet a friend of mine, Professor Binstead.”

“Don’t think I know him—what?”

“Very interesting man,” said Mr. Brewster, still with the same uncanny amiability. “He’s a dabbler in a good many things—science, phrenology, antiques. I asked him to bid for me at a sale yesterday. There was a little china figure——”

Archie’s jaw fell.

“ ‘China figure?’ ”

“Yes. The companion to one you may have noticed on my mantelpiece. I have been trying to get the pair of them for years. I should never have heard of this one if it had not been for that valet of mine, Parker. Very good of him to let me know of it, considering I had fired him. Ah, here is Binstead!” He moved to greet the small middle-aged man with the tortoise-shell-rimmed spectacles who was bustling across the lobby. “Well, Binstead—so you got it?”

“Yes.”

“I suppose the price wasn’t particularly stiff?”

“Twenty-three hundred.”

“ ‘Twenty-three hundred!’ ” Mr. Brewster seemed to reel in his tracks. “ ‘Twenty-three hundred!’ ”

“You gave me carte blanche.”

“Yes—but twenty-three hundred!”

“I could have got it for a few dollars, but unfortunately I was a little late, and, when I arrived, some young fool had bid it up to a thousand, and he stuck to me till I finally shook him off at twenty-three hundred— Why, this is the very man! Is he a friend of yours?”

Archie coughed.

“More a relation than a friend—what? Son-in-law, don’t you know.”

Mr. Brewster’s amiability had vanished.

“What foolery have you been up to now?” he demanded. “Why the devil did you bid?”

“We thought it would be rather a fruity scheme. We talked it over and came to the conclusion that it was an egg. Wanted to get hold of the rummy little object, don’t you know, and surprise you.”

“Who’s ‘we?’ ”

“Lucille and I.”

“But how did you hear of it at all?”

“Parker, the valet chappie, you know, wrote me a letter about it.”

“ ‘Parker!’ Didn’t he tell you that he had told me the figure was to be sold?”

“Absolutely not!” A sudden suspicion came to Archie. He was normally a guileless young man, but even to him the extreme fishiness of the part played by Herbert Parker had became apparent. “I say, you know, it looks to me as if friend Parker had been having us all on a bit—what? I mean to say it was jolly old Herb who tipped your son off—Bill, you know—to go and bid for the thing.”

“ ‘Bill!’ Was Bill there?”

“Absolutely in person! We were bidding against each other like the dickens till we managed to get together and get acquainted. And then this bird—this gentleman—sailed in and started to slip it across us.”

Professor Binstead chuckled—the carefree chuckle of a man who sees all those around him smitten in the pocket while he himself remains untouched.

“A very ingenious rogue, this Parker of yours, Brewster. His method seems to have been simple but masterly. I have no doubt that either he or a confederate obtained the figure and placed it with the auctioneer, and then he insured a good price for it by getting us all to bid against each other—very ingenious!”

Mr. Brewster struggled with his feelings. Then he seemed to overcome them and to force himself to look on the bright side.

“Well, anyway,” he said, “I’ve got the pair of figures, and that’s what I wanted. Is that it in that parcel?”

“This is it. I wouldn’t trust an express company to deliver it. Suppose we go up to your room and see how the two look side by side.”

They crossed the lobby to the elevator. The cloud was still on Mr. Brewster’s brow as they stepped out and made their way to his suite. Like most men who have risen from poverty to wealth by their own exertions, he objected to parting with his money unnecessarily.

Mr. Brewster unlocked the door and crossed the room. Then, suddenly, he halted, stared, and stared again. He sprang to the bell and pressed it, then stood gurgling wordlessly.

“Anything wrong, old bean?” queried Archie solicitously.

“ ‘Wrong!’ ‘Wrong!’ It’s gone!”

“ ‘Gone?’ ”

“The figure!”

The floor-waiter had manifested himself silently in answer to the bell.

“Simmons”—Mr. Brewster turned to him wildly—“has anyone been in this suite since I went away?”

“No, sir.”

“Nobody?”

“Nobody except your valet, sir—Parker. He said he had come to fetch some things away. I supposed he had come from you, sir, with instructions.”

“Get out!”

Professor Binstead had unwrapped his parcel and had placed Pongo on the table. There was a weighty silence. Archie picked up the little china figure and balanced it on the palm of his hand. It was a small thing, he reflected philosophically, but it had made quite a stir in the world.

Mr. Brewster fermented for a while without speaking.

“So,” he said at last, in a voice trembling with self-pity, “I have been to all this trouble——”

“And expense,” put in Professor Binstead gently.

“Merely to buy back something which had been stolen from me. And, owing to your damned officiousness,” he cried, turning on Archie, “I have had to pay twenty-three hundred dollars for it! I don’t know why they make such a fuss about Job. Job never had anything like you around.”

“Of course,” argued Archie, “he had one or two boils.”

“ ‘Boils!’ What are boils——”

“Dashed sorry,” murmured Archie. “Acted for the best. Meant well. And all that sort of rot.”

Professor Binstead’s mind seemed occupied, to the exclusion of all other aspects of the affair, with the ingenuity of the absent Parker.

“A cunning scheme,” he said; “a very cunning scheme. This man Parker must have a brain of no low order. I should like to feel his bumps.”

“I should like to give him some,” said the stricken Mr. Brewster. He breathed a deep breath. “Oh, well,” he said, “situated as I am, with a crook valet and an imbecile son-in-law, I suppose I ought to be thankful that I’ve still got my own property, even if I have had to pay twenty-three hundred dollars for the privilege of keeping it.” He rounded on Archie, who was in a reverie. The thought of the unfortunate Bill had just crossed Archie’s mind. It would be many moons, many weary moons, before Mr. Brewster would be in a suitable mood to listen sympathetically to the story of Love’s young dream. “Give me that figure!”

Archie continued to toy absently with Pongo. He was wondering now how best to break this sad occurrence to Lucille. It would be a disappointment for the poor girl.

“Give me that figure!”

Archie started violently. There was an instant in which Pongo seemed to hang suspended, like Mohammed’s coffin, between heaven and earth; then the force of gravity asserted itself. Pongo fell with a sharp crack and disintegrated.

“Well,” said Professor Binstead cheerfully, breaking the grim silence, “if you will give me your check, Brewster, I think I will be going. Two thousand three hundred dollars. Make it open, if you will, and then I can run round the corner and cash it before lunch. That will be capital.”

The next escapade of Archie in America will appear in September Cosmopolitan.

Madame Eulalie’s Rare Plums

Madame Eulalie’s Rare Plums