Cosmopolitan Magazine, April 1930

“ WHAT ho, Jeeves!” I said, entering the room where he waded knee-deep in suitcases and shirts and winter suitings, like a sea beast among rocks. “Packing?”

“Yes, sir,” replied the honest fellow, for there are no secrets between us.

“Pack on!” I said approvingly. “Pack, Jeeves, pack with care. Pack in the presence of the passenjare.” And I rather fancy I added the words “Tra-la!” for I was in merry mood.

Every year, starting about the middle of November, there is a good deal of anxiety and apprehension among owners of the better class of country house throughout England as to who will get Bertram Wooster’s patronage for the Christmas holidays. It may be one, or it may be another. As my aunt Dahlia says, you never know where the blow will fall.

This year, however, I had decided early. It couldn’t have been later than November tenth when a sigh of relief went up from a dozen stately homes as it became known that the short straw had been drawn by Sir Reginald Witherspoon, Bart., of Bleaching Court, Upper Bleaching, Hants.

In coming to the decision to give this Witherspoon my custom, I had been actuated by several reasons, not counting the fact that, having married Aunt Dahlia’s husband’s younger sister Katherine, he is by way of being a sort of uncle of mine. In the first place the Bart. does one extraordinarily well, both browsing and sluicing being above criticism. Then, again, his stables always contain something worth riding, which is a consideration. And thirdly, there is no danger of getting lugged into a party of amateur waits and having to tramp the countryside in the rain singing: “When Shepherds Watched Their Flocks by Night.” Or, for the matter of that: “Noël! Noël!”

All these things counted with me, but what really drew me to Bleaching Court like a magnet was the knowledge that young Tuppy Glossop would be among those present.

I feel sure I have told you before about this black-hearted bird, but I will give you the strength of it once again, just to keep the records straight. He was the fellow, if you remember, who, ignoring a lifelong friendship, bet me one night at the Drones’ that I wouldn’t swing myself across the swimming bath by the ropes and rings and then, with almost inconceivable treachery, went and looped back the last ring, causing me to drop into the fluid and ruin one of the nattiest suits of dress clothes in London.

To execute a fitting vengeance on this bloke had been the ruling passion of my life ever since.

“You are bearing in mind, Jeeves,” I said, “the fact that Mr. Glossop will be at Bleaching?”

“Yes, sir.”

“And consequently, are not forgetting to put in the Giant Squirt?”

“No, sir.”

“Nor the Luminous Rabbit?”

“No, sir.”

“Good! I am rather pinning my faith on the Luminous Rabbit, Jeeves. I hear excellent reports of it on all sides. You wind it up and put it in somebody’s room in the night watches, and it shines in the dark and jumps about, making odd, squeaking noises. The whole performance being, I should imagine, well calculated to scare young Tuppy into a decline.”

“Very possibly, sir.”

“Should that fail, there is always the Giant Squirt. We must leave no stone unturned to put it across the man somehow,” I said. “The Wooster honor is at stake.”

I would have spoken further on this subject, but just then the front doorbell buzzed.

“I’ll answer it,” I said. “I expect it’s Aunt Dahlia. She phoned that she would be calling this morning.”

It was not Aunt Dahlia. It was a telegraph boy with telegram. I opened it, read it and carried it back to the bedroom, the brow a bit knitted.

“Jeeves,” I said, “a rummy communication has arrived. From Mr. Glossop.”

“Indeed, sir?”

“I will read it to you. Handed in at Upper Bleaching.

“Message runs as follows: ‘When you come tomorrow, bring my football boots. Also, if humanly possible, Irish water spaniel. Urgent. Regards. Tuppy.’ What do you make of that, Jeeves?”

“As I interpret the document, sir, Mr. Glossop wishes you, when you come tomorrow, to bring his football boots. Also, if humanly possible, an Irish water spaniel. He hints that the matter is urgent, and sends his regards.”

“Yes, that’s how I read it, too. But why football boots?”

“Perhaps Mr. Glossop wishes to play football, sir.”

I considered this.

“Yes,” I said. “That may be the solution. But why would a man, staying peacefully at a country house, suddenly develop a craving to play football?”

“I could not say, sir.”

“And why an Irish water spaniel?”

“There again I fear I can hazard no conjecture, sir.”

“What is an Irish water spaniel?”

“A water spaniel of a variety bred in Ireland, sir.”

“You think so?”

“Yes, sir.”

“Well, perhaps you’re right. But why should I toil about the place collecting dogs—of whatever nationality—for young Tuppy? Does he think I’m Santa Claus? Is he under the impression that my feelings towards him, after that Drones’ Club incident, are those of kindly benevolence? Irish water spaniels, indeed! Pshaw!”

“Sir?”

“Pshaw, Jeeves.”

“Very good, sir.”

The front doorbell buzzed again.

“Our busy morning, Jeeves.”

“Yes, sir.”

“All right. I’ll go.”

This time it was Aunt Dahlia. She charged in with the air of a woman with something on her mind, giving tongue, in fact, while actually on the very doormat.

“Bertie,” she boomed, in that ringing voice of hers which cracks windowpanes and upsets vases, “I’ve come about that young hound, Glossop.”

“It’s quite all right, Aunt Dahlia,” I replied soothingly. “I have the situation well in hand. The Giant Squirt and the Luminous Rabbit are being packed.”

“I don’t know what you’re talking about, and I don’t for a moment suppose you do, either,” said the relative, somewhat brusquely, “but if you’ll kindly stop gibbering for a moment I’ll tell you what I mean. I have had a most disturbing letter from Katherine. About this reptile. Of course, I haven’t breathed a word to Angela. She’d hit the ceiling.”

This Angela is Aunt Dahlia’s daughter. She and young Tuppy are generally supposed to be more or less engaged, though nothing definitely Morning Post-ed yet.

“Why?” I said.

“Why what?”

“Why would Angela hit the ceiling?”

“Well, wouldn’t you, if you were practically engaged to a fiend in human shape and somebody told you he had gone off to the country and was flirting with a dog-girl?”

“With a—what was that once again?”

“A dog-girl. One of these dashed open-air flappers in thick boots and tailor-made tweeds who infest the rural districts and go about the place followed by packs of assorted dogs. I used to be one of them myself in my younger days, so I know how dangerous they are. Her name is Dalgleish. Old Colonel Dalgleish’s daughter. They live near Bleaching.”

I saw a gleam of daylight.

“Then that must be what his telegram was about. He’s just wired, asking me to bring down an Irish water spaniel. A Christmas present for this girl, no doubt.”

“Probably. Katherine tells me he seems to be infatuated with her. She says he follows her about like one of her dogs, looking like a tame cat and bleating like a sheep.”

“Quite the private zoo, what?”

“Bertie,” said Aunt Dahlia, and I could see her generous nature was stirred to its depths, “one more crack like that out of you, and I shall forget that I am an aunt and hand you one.”

I became soothing. I gave her the old oil.

“I shouldn’t worry,” I said. “There’s probably nothing in it. Whole thing no doubt much exaggerated.”

“You think so, eh? Well, you know what he’s like. You remember the trouble we had when he ran after that singing woman.”

I recollected the case. You will find it elsewhere in the archives. Cora Bellinger was the female’s name. She was studying for opera, and young Tuppy thought highly of her. Fortunately, however, she punched him in the eye during Beefy Bingham’s clean, bright entertainment in Bermondsey East, and love died.

“Besides,” said Aunt Dahlia, “there’s something I haven’t told you. Just before he went to Bleaching, he and Angela quarreled.”

“They did?”

“Yes. I got it out of Angela this morning. She was crying her eyes out, poor angel. It was something about her last hat. As far as I could gather, he told her it made her look like a Pekingese, and she told him she never wanted to see him again in this world or the next. And he said ‘Right ho!’ and breezed off.

“I can see what has happened. This dog-girl has caught him on the rebound, and unless something is done quick, anything may happen. So place the facts before Jeeves, and tell him to take action the moment you get down there.”

I am always a little piqued, if you know what I mean, at this assumption on the relative’s part that Jeeves is so dashed essential on these occasions. My manner, therefore, as I replied, was a bit on the crisp side.

“Jeeves’ services will not be required,” I said. “I can handle this business. The program which I have laid out will be quite sufficient to take young Tuppy’s mind off love-making. It is my intention to insert the Luminous Rabbit in his room at the first opportunity that presents itself.

“The Luminous Rabbit shines in the dark and jumps about, making odd, squeaking noises. It will sound to young Tuppy like the Voice of Conscience, and I anticipate that a single treatment will make him retire into a nursing home for a couple of weeks or so. At the end of which period, he will have forgotten the bally girl.”

“Bertie,” said Aunt Dahlia, with a sort of frozen calm, “you are the Abysmal Chump. Listen to me. It’s simply because I am fond of you and have influence with the lunacy commissioners that you weren’t put in a padded cell years ago. Bungle this business, and I withdraw my protection. Can’t you understand that this thing is far too serious for any fooling about? Angela’s whole happiness is at stake. Do as I tell you, and put it up to Jeeves.”

“Just as you say, Aunt Dahlia,” I said stiffly.

“All right, then. Do it now.”

I went back to the bedroom.

“Jeeves,” I said, and I did not trouble to conceal my chagrin, “you need not pack the Luminous Rabbit.”

“Very good, sir.”

“Nor the Giant Squirt.”

“Very good, sir.”

“They have been subjected to destructive criticism, and the zest has gone. Oh, and Jeeves. Mrs. Travers wishes you, on arriving at Bleaching Court, to disentangle Mr. Glossop from a dog-girl.”

“Very good, sir. I will attend to the matter and will do my best to give satisfaction.”

That Aunt Dahlia had not exaggerated the perilous nature of the situation was made clear to me on the following afternoon. Jeeves and I drove down to Bleaching in the two-seater, and we were tooling along about halfway between the village and the Court when suddenly there appeared ahead of us a sea of dogs and in the middle of it young Tuppy frisking round one of those largish, corn-fed girls.

He was bending toward her in a devout sort of way, and even at a considerable distance I could see that his ears were pink. His attitude, in short, was unmistakably that of a man endeavoring to push a good thing along: and when I came closer and noted that the girl wore tailor-made tweeds and thick boots, I had no further doubts.

“You observe, Jeeves?” I said in a low, significant voice.

“You observe, Jeeves?” I said in a low, significant voice.

“Yes, sir.”

“The girl, what?”

“Yes, sir.”

I tootled amiably on the horn and yodeled a bit. They turned—Tuppy, I fancied, not any too pleased.

“Oh, hullo, Bertie,” he said.

“Hullo,” I said.

“My friend Bertie Wooster,” said Tuppy to the girl, in what seemed rather an apologetic manner. You know—as if he would have preferred to hush me up.

“Hullo,” said the girl.

“Hullo,” I said.

“Hullo, Jeeves,” said Tuppy.

“Good afternoon, sir,” said Jeeves.

There was a somewhat constrained silence.

“Well, good-by, Bertie,” said young Tuppy. “You’ll be wanting to push along, I expect.”

We Woosters can take a hint as well as the next man.

“See you later,” I said.

“Oh, rather,” said Tuppy.

I set the machinery in motion again, and we rolled off.

“Sinister, Jeeves,” I said. “You noticed that the subject was looking like a stuffed frog?”

“Yes, sir.”

“And gave no indication of wanting us to stop and join the party?”

“No, sir.”

“I think Aunt Dahlia’s fears are justified. The thing seems serious.”

“Yes, sir.”

“Well, strain the brain, Jeeves.”

“Very good, sir.”

It wasn’t till I was dressing for dinner that night that I saw young Tuppy again. He trickled in just as I was arranging the tie.

“Hullo!” I said.

“Hullo!” said Tuppy.

“Who was the girl?” I asked, in that casual, snaky way of mine. Offhand, I mean.

“A Miss Dalgleish,” said Tuppy, and I noticed that he blushed a spot.

“Staying here?”

“No. She lives in that house just before you come to this place. Did you bring my football boots?”

“Yes. Jeeves has got them somewhere.”

“And the water spaniel?”

“Sorry. No water spaniel.”

“Dashed nuisance. She’s set her heart on an Irish water spaniel.”

“Well, what do you care?”

“I wanted to give her one.”

“Why?”

Tuppy became a trifle haughty. Frigid. The rebuking eye.

“Colonel and Mrs. Dalgleish,” he said, “have been very kind to me since I got here. They have entertained me. I naturally wish to make some return for their hospitality. I don’t want them to look upon me as one of those ill-mannered modern young men you read about in the papers, who grab everything they can lay their hooks on and never buy back. If people ask you to lunch and tea and what not, they appreciate it if you make them some little present in return.”

“Well, give them your football boots. In passing, why did you want the bally things?”

“I’m playing in a match next Thursday.”

“Down here?”

“Yes. Upper Bleaching versus Hockley-cum-Meston. Apparently it’s the big game of the year.”

“How did you get roped in?”

“I happened to mention in the course of conversation the other day that, when in London, I generally turn out on Saturdays for the Old Austinians, and Miss Dalgleish seemed rather keen that I should help the village.”

“Which village?”

“Upper Bleaching, of course.”

“Ah, then you’re going to play for Hockley?”

“You needn’t be funny, Bertie. You may not know it, but I’m pretty hot stuff on the football field. Oh, Jeeves.”

“Sir?” said Jeeves, entering right center.

“Mr. Wooster tells me you have my football boots.”

“Yes, sir. I have placed them in your room.”

“Thanks. Jeeves, do you want to make a bit of money?”

“Yes, sir.”

“Then put a trifle on Upper Bleaching for the annual encounter with Hockley-cum-Meston next Thursday,” said Tuppy, exiting with swelling bosom.

“Mr. Glossop is going to play on Thursday,” I explained, as the door closed.

“So I was informed in the Servants’ Hall, sir.”

“Oh? And what’s the general feeling there about it?”

“The impression I gathered, sir, was that the Servants’ Hall considers Mr. Glossop ill-advised.”

“Why’s that?”

“I am informed by Mr. Mulready, Sir Reginald’s butler, sir, that this contest differs in some respects from the ordinary football game. Owing to the fact that there has existed for many years considerable animus between the two villages, the struggle is conducted, it appears, on somewhat looser and more primitive lines than is usually the case when two teams meet in friendly rivalry. The primary object of the players, I am given to understand, is not so much to score points as to inflict violence.”

“Good Lord, Jeeves!”

“Such appears to be the case, sir. The game is one that would have a great interest for the antiquarian. It was played first in the reign of King Henry the Eighth, when it lasted from noon till sundown over an area covering several square miles. Seven deaths resulted on that occasion.”

“Seven!”

“Not inclusive of two of the spectators, sir. In recent years, however, the casualties appear to have been confined to broken limbs and other minor injuries. The opinion of the Servants’ Hall is that it would be more judicious on Mr. Glossop’s part were he to refrain from mixing himself up in the affair.”

I was more or less aghast. I mean to say, while I had made it my mission in life to get back at young Tuppy for that business at the Drones’, there still remained certain faint vestiges, if vestiges is the word I want, of the old esteem.

Besides, there are limits to one’s thirst for vengeance. Deep as my resentment was for the ghastly outrage he had perpetrated on me, I had no wish to see him toddle unsuspiciously into the arena and get all chewed up by wild villagers.

A Tuppy scared stiff by a Luminous Rabbit—yes. Excellent business. The happy ending, in fact. But a Tuppy carried off on a stretcher in half a dozen pieces—no. Quite a different matter. All wrong. Not to be considered for a moment.

Obviously, then, a kindly word of warning while there was yet time was indicated. I buzzed off to his room forthwith, and found him toying dreamily with the football boots.

I put him in possession of the facts.

“What you had better do—and the Servants’ Hall thinks the same,” I said—“is fake a sprained ankle on the eve of the match.”

He looked at me in an odd sort of way. “You suggest that, when Miss Dalgleish is trusting me, relying on me, looking forward with eager, girlish enthusiasm to seeing me help her village on to victory, I should let her down with a thud?”

I was pleased with his ready intelligence. “That’s the idea,” I said.

“Faugh!” said Tuppy—the only time I’ve ever heard the word.

“How do you mean, ‘Faugh’?” I asked.

“Bertie,” said Tuppy, “what you tell me merely makes me all the keener for the fray. A warm game is what I want. I welcome this sporting spirit on the part of the opposition. I shall enjoy a spot of roughness. It will enable me to give of my best.

“Do you realize,” said young Tuppy, vermilion to the gills, “that she will be looking on? And do you know how that will make me feel? It will make me feel like some knight of old jousting under the eyes of his lady. Do you suppose that Sir Lancelot or Sir Galahad, when there was a tourney scheduled for the following Thursday, pretended they had sprained their ankles just because the thing was likely to be a bit rough?”

“Don’t forget that in the reign of King Henry the Eighth——”

“Never mind about the reign of King Henry the Eighth. All I care about is that it’s Upper Bleaching’s turn this year to play in colors, so I shall be able to wear my Old Austinian shirt. Light blue, Bertie, with broad orange stripes. I shall look like something, I tell you.”

“But what?”

“Bertie,” said Tuppy, now becoming purely gaga, “I may as well tell you that I’m in love at last. This is the real thing. I have found my mate. All my life I have dreamed of meeting some sweet open-air girl with all the glory of the English countryside in her eyes, and I have found her.

“How different she is, Bertie, from these hothouse, artificial London girls! Would they stand in the mud on a winter afternoon, watching a football match? Would they know what to give an Alsatian for fits? Would they tramp ten miles a day across the fields and come back as fresh as paint? No!”

“Well, why should they?”

“Bertie, I’m staking everything on this game on Thursday. At the moment, I have an idea that she looks on me as something of a weakling, simply because I got a blister on my foot the other afternoon and had to take the bus back from Hockley. But when she sees me going through the rustic opposition like a devouring flame, will that make her think a bit? Will that open her eyes? What?”

“What?”

“I said ‘What?’ ”

“So did I.”

“I meant, Won’t it?”

“Oh, rather.”

Here the dinner gong sounded, not before I was ready for it.

Judicious inquiries during the next couple of days convinced me that the Servants’ Hall at Bleaching Court, in advancing the suggestion that young Tuppy, born and bred in the gentler atmosphere of the metropolis, would do well to keep out of local disputes and avoid the football field on which these were to be settled, had not spoken idly. It had weighed its words and said the sensible thing. Feeling between the two villages undoubtedly ran high, as they say.

You know how it is in these remote rural districts. Life tends at times to get a bit slow. There’s nothing much to do in the long winter evenings but listen to the radio and brood on what a tick your neighbor is. You find yourself remembering how Farmer Giles did you down over the sale of your pig, and Farmer Giles finds himself remembering that it was your son, Ernest, who bunged the half-brick at his horse on the second Sunday before Septuagesima. And so on and so forth.

How this particular feud had started, I don’t know, but the season of peace and good will found it in full blast. The only topic of conversation in Upper Bleaching was Thursday’s game, and the citizenry seemed to be looking forward to it in a spirit that can only be described as ghoulish. And it was the same in Hockley-cum-Meston.

I paid a visit to Hockley-cum-Meston on the Wednesday, being rather anxious to take a look at the inhabitants and see how formidable they were. I was shocked to observe that practically every second male might have been the Village Blacksmith’s big brother. The muscles on their brawny arms were obviously strong as iron bands, and the way the company at the Green Pig, where I looked in incognito for a spot of beer, talked about the forthcoming sporting contest was enough to chill the blood of anyone who had a pal who proposed to fling himself into the fray. It sounded rather like Attila and a few of his Huns sketching out their next campaign.

I went back to Jeeves with my mind made up.

“Jeeves,” I said, “you, who had the job of drying and pressing those dress clothes of mine, are aware that I have suffered much at young Tuppy Glossop’s hands. By rights, I suppose, I ought to be welcoming the fact that the Wrath of Heaven is now hovering over him in this fearful manner.

“But the view I take of it is that Heaven looks like overdoing it. Heaven’s idea of a fitting retribution is not mine. In my most unrestrained moments I never wanted the poor blighter assassinated. And the idea in Hockley-cum-Meston seems to be that a good opportunity has arisen of making it a bumper Christmas for the local undertaker.

“There was a fellow with red hair at the Green Pig this afternoon who might have been the undertaker’s partner, the way he talked. We must act, and speedily, Jeeves. We must put a bit of a jerk in it and save young Tuppy in spite of himself.”

“What course would you advocate, sir?”

“I’ll tell you. He refuses to do the sensible thing and slide out, because the girl will be watching the game and he imagines, poor lizard, that he is going to shine and impress her. So we must employ guile. You must go up to London today, Jeeves, and tomorrow morning you will send a telegram, signed ‘Angela,’ which will run as follows. Jot it down. Ready?”

“Yes, sir.”

“ ‘So sorry——’ ” I pondered. “What would a girl say, Jeeves, who, having had a row with the bird she was practically engaged to, because he told her she looked like a Pekingese in her new hat, wanted to extend the olive branch?”

“ ‘So sorry I was cross,’ sir, would, I fancy, be the expression.”

“Strong enough, do you think?”

“Possibly the addition of the word ‘darling’ would give the necessary verisimilitude, sir.”

“Right. Resume the jotting. ‘So sorry I was cross, darling.’ No; wait, Jeeves. Scratch that out. I see where we have gone off the rails. I see where we are missing a chance to make this the real Tabasco. Sign the telegram not ‘Angela’ but ‘Travers.’ ”

“Very good, sir.”

“Or, rather, ‘Dahlia Travers.’ And this is the body of the communication. ‘Please return at once.’ ”

“ ‘Immediately’ would be more economical, sir. Only one word. And it has a stronger ring.”

“True. Jot on, then. ‘Please return immediately. Angela in a hell of a state.’ ”

“I would suggest ‘Seriously ill,’ sir.”

“All right. ‘Seriously ill.’ ‘Angela seriously ill. Keeps calling for you and says you were quite right about hat.’ ”

“If I might suggest, sir——?”

“Well, go ahead.”

“I fancy the following would meet the case. ‘Please return immediately. Angela seriously ill. High fever and delirium. Keeps calling your name piteously and saying something about a hat and that you were quite right. Please catch earliest possible train. Dahlia Travers.’ ”

“That sounds all right.”

“Yes, sir.”

“You like that ‘piteously’? You don’t think ‘incessantly’?”

“No, sir. ‘Piteously’ is the mot juste.”

“All right. You know. Well, send it off in time to get here at two-thirty.”

“Yes, sir.”

“Two-thirty, Jeeves; you see the devilish cunning?”

“No, sir.”

“I will tell you. If the telegram arrived earlier, he would get it before the game. By two-thirty, however, he will have started for the ground. I shall hand it to him the moment there is a lull in the battle. By that time he will have begun to get some idea of what a football match between Upper Bleaching and Hockley-cum-Meston is like, and the thing ought to work like magic. I can’t imagine anyone who has been sporting awhile with those thugs I saw yesterday not welcoming any excuse to call it a day. You follow me?”

“Yes, sir.”

“Very good, Jeeves.”

“Very good, sir.”

You can always rely on Jeeves. Two-thirty I had said, and two-thirty it was. The telegram arrived almost on the minute.

I was going to my room to change into something warmer at the moment, and I took it up with me. Then into the heavy tweeds and off in the car to the field of play. I got there just as the two teams were lining up, and half a minute later, the whistle blew and the war was on.

What with one thing and another—having been at a school where they didn’t play it and so forth—Rugby football is a game I can’t claim absolutely to understand in all its niceties, if you know what I mean. I can follow the broad, general principles, of course.

I mean to say, I know that the main scheme is to work the ball down the field somehow and deposit it over the line at the other end, and that, in order to squelch this program, each side is allowed to put in a certain amount of assault and battery and do things to its fellow man which, if done elsewhere, would result in fourteen days without the option, coupled with some strong remarks from the Bench. But there I stop. What you might call the science of the thing is to Bertram Wooster a sealed book. However, I am informed by experts that on this occasion there was not enough science for anyone to notice.

There had been a good deal of rain in the last few days, and the going appeared to be a bit sticky. In fact, I have seen swamps that were drier than this particular bit of ground. The red-haired bloke whom I had encountered in the pub paddled up and kicked off amidst cheers from the populace, and the ball went straight to where Tuppy was standing, a pretty color scheme in light blue and orange. Tuppy caught it neatly and hoofed it back, and it was at this point that I understood that an Upper Bleaching versus Hockley-cum-Meston game had certain features not usually seen on the football field.

For Tuppy, having done his bit, was just standing there looking modest, when there was a thunder of large feet and the red-haired bird, galloping up, seized him by the neck, hurled him to earth and fell on him. I had a glimpse of Tuppy’s face, as it registered horror, dismay and a general suggestion of stunned dissatisfaction with the scheme of things, and then he disappeared.

By the time he had come to the surface, a sort of mob warfare was going on at the other side of the field. Two assortments of sons-of-the-soil had got their heads down and were shoving earnestly against each other, with the ball somewhere in the middle.

Tuppy wiped a fair portion of Hampshire out of his eye, peered round him in a dazed kind of way, saw the mass meeting and ran towards it, arriving just in time for a couple of heavyweights to gather him in and give him the mud-treatment again. This placed him in an admirable position for a third heavyweight to kick him in the ribs with a boot like a violin case. The red-haired man then fell on him. It was all good, brisk play, and looked fine from my side of the ropes.

I saw now where Tuppy had made his mistake. He was too dressy. On occasions such as this it is safest not to be conspicuous, and that blue-and-orange shirt rather caught the eye. A sober beige, blending with the color of the ground, was what his best friends would have recommended.

And in addition to the fact that his costume attracted attention, I rather think that the men of Hockley-cum-Meston resented his being on the field at all. They felt that, as a non-local, he had butted in on a private fight and had no business there.

At any rate, it certainly appeared to me that they were giving him preferential treatment. After each of those shoving-bees to which I have alluded, when the edifice caved in and tons of humanity wallowed in a tangled mass in the juice, the last soul to be excavated always seemed to be Tuppy. And on the rare occasions when he actually managed to stand upright for a moment, somebody—generally the red-haired man—invariably sprang to the congenial task of spilling him again.

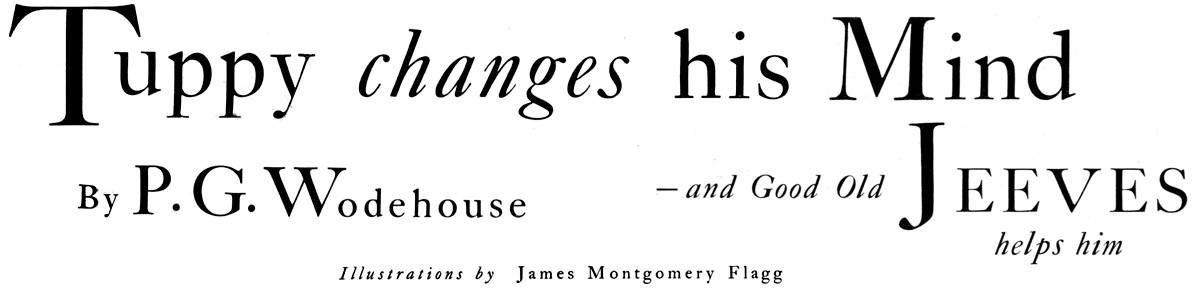

In fact, it was beginning to look as though that telegram would come too late to save a human life, when an interruption occurred. Play had worked round close to where I was standing, and there had been the customary collapse of all concerned, with Tuppy at the bottom of the basket, as usual. But this time, when they got up and started to count the survivors, a sizable cove in what had once been a white shirt remained on the ground. And a hearty cheer went up from a hundred patriotic throats as the news spread that Upper Bleaching had drawn first blood.

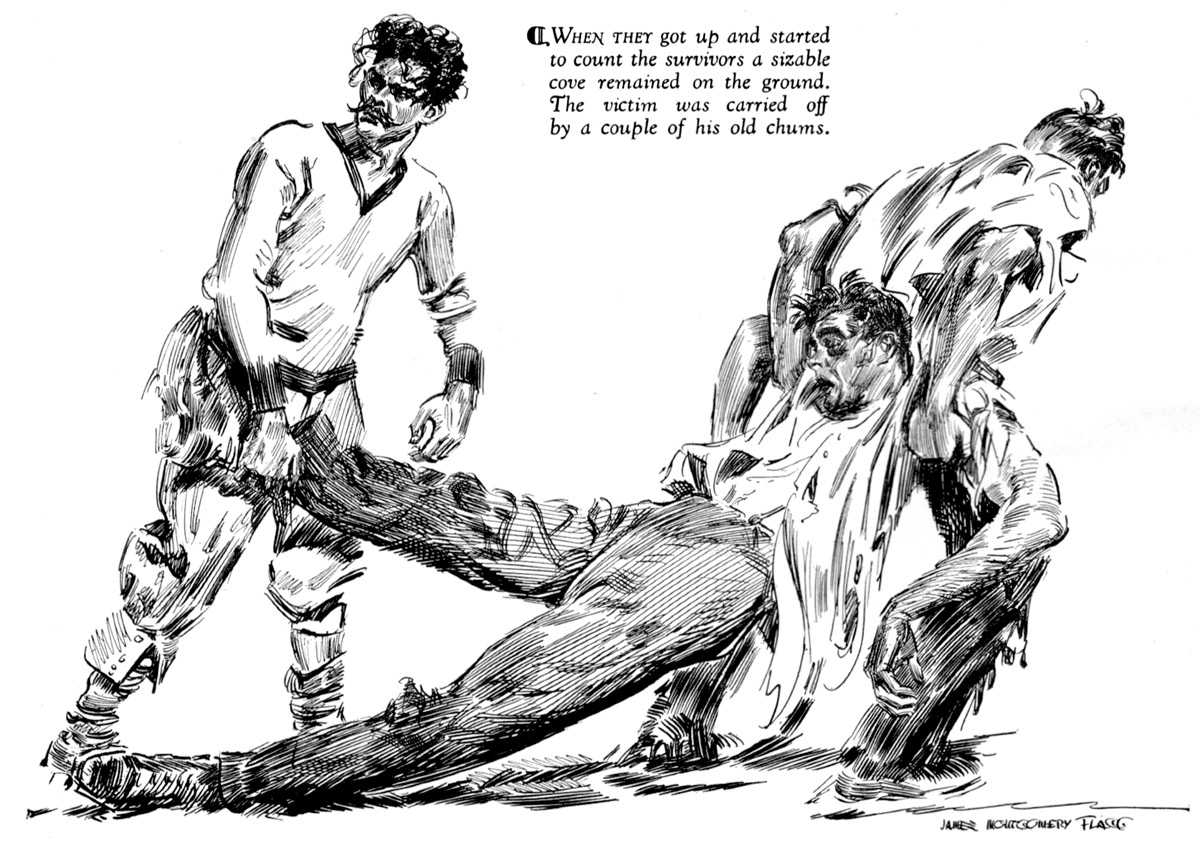

The victim was carried off by a couple of his old chums, and the rest of the players sat down and pulled their stockings up and thought of life for a bit. The moment had come, it seemed to me, to remove Tuppy from the abattoir, and I hopped over the ropes and toddled to where he sat scraping mud from his wishbone.

His air was that of a man who has been passed through a wringer, and his eyes, what you could see of them, had a strange, smoldering gleam. He was so crusted with alluvial deposits that one realized how little a mere bath would ever be able to effect. To fit him to take his place once more in polite society, he would certainly have to be sent to the cleaner’s. Indeed, it was a moot point whether it wouldn’t be simpler just to throw him away.

“Tuppy, old man,” I said.

“Eh?” said Tuppy.

“A telegram for you.”

“Eh?”

“I’ve got a wire here that came after you left the house.”

“Eh?” said Tuppy.

I stirred him up a trifle with the ferrule of my stick, and he seemed to come to life.

“Be careful what you’re doing, you silly ass,” he said, in part. “I’m one solid bruise. What are you gibbering about?”

“A telegram has come for you. I think it may be important.”

He snorted in a bitter sort of way. “Do you suppose I’ve time to read telegrams now?”

“But this one may be frightfully urgent,” I said. “Here it is.”

But, if you understand me, it wasn’t. How I had happened to do it, I don’t know, but apparently, in changing the upholstery, I had left it in my other coat.

“Oh, my gosh,” I said. “I’ve left it behind.”

“It doesn’t matter.”

“But it does. It’s probably something you ought to read at once. Immediately, if you know what I mean. If I were you, I’d just say a few words of farewell to the murder squad and come back to the house right away.”

He raised his eyebrows. At least, I think he must have done so, because the mud on his forehead stirred a little, as if something was going on underneath it.

“Do you imagine,” he said, “that I would slink away under her very eyes? Good Lord! Besides,” he went on, in a quiet, meditative voice, “there is no power on earth that could get me off this field until I’ve thoroughly disemboweled that red-haired bounder. Have you noticed how he keeps tackling me when I haven’t got the ball?”

“Isn’t that right?”

“Of course it’s not right. Never mind! A bitter retribution awaits that bird. I’ve had enough of it. From now on I assert my personality.”

“I’m a bit foggy as to the rules of this pastime,” I said. “Are you allowed to bite him?”

“I’ll try and see what happens,” said Tuppy, struck with the idea and brightening a little.

At this point, the pallbearers returned and fighting became general again all along the Front.

There’s nothing like a spot of rest and what you might call folding of the hands for freshening up the shop-soiled athlete. The dirty work, resumed after this brief breather, started off with an added vim which it did one good to see. And the life and soul of the party was Tuppy.

You know, only meeting a fellow at luncheon or at the races or loafing round country houses and so forth, you don’t get on to his hidden depths, if you know what I mean. Until this moment, if asked, I would have said that Tuppy Glossop was, on the whole, essentially a pacific sort of bloke, with little or nothing of the tiger of the jungle in him. Yet here he was, running to and fro with fire streaming from his nostrils, a positive danger to traffic.

Yes, absolutely. Encouraged by the fact that the referee either was filled with the spirit of Live and Let Live or else had got his whistle choked up with mud, the result being that he appeared to regard the game with a sort of calm detachment, Tuppy was putting in some very impressive work. Even to me, knowing nothing of the finesse of the thing, it was plain that if Hockley-cum-Meston wanted the happy ending they must eliminate young Tuppy at the earliest possible moment.

And I will say for them that they did their best, the red-haired man being particularly assiduous. But Tuppy was made of durable material. Every time the opposition talent ground him into the mire and sat on his head, he rose on stepping-stones of his dead self, if you follow me, to higher things. And in the end it was the red-haired bloke who did the dust-biting.

I couldn’t tell you exactly how it happened, for by this time the shades of night were drawing in a bit and there was a dollop of mist rising, but one moment the fellow was hare-ing along, apparently without a care in the world, and then suddenly Tuppy had appeared from nowhere and was sailing through the air at his neck. They connected with a crash and a slither, and a little later the red-haired bird was hopping off, supported by a brace of friends.

After that, there was nothing to it. Upper Bleaching, thoroughly bucked, became busier than ever. There was a lot of earnest work in a sort of inland sea down at the Hockley end of the field, and then a kind of tidal wave poured over the line, and when the bodies had been removed and the tumult and the shouting had died, there was young Tuppy lying on the ball.

And that, with exception of a few spots of mayhem in the last five minutes, concluded the proceedings.

I drove back to the Court in rather what you might term a pensive frame of mind. Things having happened as they had happened, there seemed to me a goodish bit of hard thinking to be done.

There was a servitor of sorts in the hall, when I arrived, and I asked him to send up a whisky-and-soda, strongish, to my room. The old brain, I felt, needed stimulating. And about ten minutes later there was a knock at the door, and in came Jeeves, bearing tray and materials.

“Hullo, Jeeves,” I said, surprised. “Are you back?”

“Yes, sir.”

“When did you get here?”

“Some little while ago, sir. Was it an enjoyable game, sir?”

“In a sense, Jeeves,” I said, “yes. Replete with interest and all that, if you know what I mean. But I fear that, owing to a touch of carelessness on my part, the worst has happened. I left the telegram in my other coat, so young Tuppy remained in action throughout.”

“Was he injured, sir?”

“Worse than that, Jeeves. He was the star of the game. Toasts, I should imagine, are now being drunk to him at every pub in the village. So spectacularly did he play—in fact, so heartily did he joust—that I can’t see the girl not being all over him. Unless I am greatly mistaken, the moment they meet, she will exclaim, ‘My hero!’ and fall into his bally arms.”

“Indeed, sir?”

I didn’t like the man’s manner. Too calm. Unimpressed. A little leaping about with fallen jaw was what I had expected my words to produce, and I was on the point of saying as much when the door opened again and Tuppy limped in.

He was wearing an ulster over his football things, and I wondered why he had come to pay a social call on me instead of proceeding straight to the bathroom. He eyed my glass in a wolfish sort of way.

“Whisky?” he said, in a hushed voice.

“And soda.”

“Bring me one, Jeeves,” said young Tuppy. “A large one.”

“Very good, sir.”

Tuppy wandered to the window and looked out into the gathering darkness, and for the first time I perceived that he had a grouch of some description. You can generally tell by a fellow’s back. Humped. Bent. Bowed down with weight of woe, if you follow me.

“What’s the matter?” I asked.

Tuppy emitted a mirthless.

“Oh, nothing much,” he said. “My faith in woman is dead, that’s all.”

“It is?”

“You jolly well bet it is. Women are a washout. I see no future for the sex, Bertie. Blisters, all of them.”

“Er—even the Dogsbody girl?”

“Her name,” said Tuppy, a little stiffly, “is Dalgleish, if it happens to interest you. And if you want to know something else, she’s the worst of the lot.”

“My dear chap!”

Tuppy turned. Beneath the mud, I could see that his face was drawn and, to put it in a nutshell, wan.

“Do you know what happened, Bertie?”

“What?”

“She wasn’t there.”

“Where?”

“At the match, you silly ass.”

“Not at the match?”

“No.”

“You mean, not among the throng of eager spectators?”

“Of course I mean not among the spectators. Did you think I expected her to be playing?”

“But I thought the whole scheme of the thing——”

“So did I. My gosh!” said Tuppy, laughing another of those hollow ones, “I work myself to the bone for her sake. I allow a mob of homicidal maniacs to kick me in the ribs and stroll about on my face. And then when I have braved a fate worse than death, so to speak, all to please her, I find that she didn’t bother to come and watch the game.

“She got a phone call from London from somebody who said he had located an Irish water spaniel, and up she popped in her car, leaving me flat. I met her just now outside her house, and she told me. And all she could think of was that she was as sore as a sunburnt neck because she had had her trip for nothing. Apparently it wasn’t an Irish water spaniel at all. Just an ordinary English water spaniel.

“And to think I fancied I loved a girl like that. A nice life partner she would make! When pain and anguish wring the brow, a ministering angel thou—I don’t think! Why, if a man married a girl like that and happened to get stricken by some dangerous illness, would she smooth his pillow and press cooling drinks on him? Not a chance! She’d be off somewhere trying to buy Siberian eel-hounds. I’m through with women.”

I saw that the moment had come to put in a word for the old firm.

“My cousin Angela’s not a bad sort, Tuppy,” I said, in a grave, elder-brotherly kind of way. “Not altogether a bad egg, Angela, if you look at her squarely. I had always been hoping that she and you . . . And I know my aunt Dahlia felt the same.”

Tuppy’s bitter sneer cracked the topsoil.

“Angela!” he woofed. “Don’t talk to me about Angela. Angela’s a rag and a bone and a hank of hair and an A 1 scourge, if you want to know. She gave me the push. Yes, she did. Simply because I had the manly courage to speak out candidly on the subject of that ghastly lid she was chump enough to buy.

“It made her look like a Peke, and I told her it made her look like a Peke. And instead of admiring me for my fearless honesty she bunged me out on my ear. Faugh!”

“She did?” I said.

“She jolly well did,” said young Tuppy. “At four-sixteen p.m. on Tuesday the seventeenth.”

“By the way, old man,” I said. “I’ve found that telegram.”

“What telegram?”

“The one I told you about.”

“Oh, that one?”

“Yes, that’s the one.”

“Well, let’s have a look at the beastly thing.”

I handed it over, watching him narrowly. And suddenly, as he read, I saw him wabble. Stirred to the core. Obviously.

“Anything important?” I said.

“Bertie,” said young Tuppy, in a voice that quivered with strong emotion, “my recent remarks re your cousin Angela. Wash them out. Cancel them. Look on them as not spoken. I tell you, Bertie, Angela’s all right. An angel in human shape, and that’s official. Bertie, I’ve got to get up to London. She’s ill.”

“Ill?”

“High fever and delirium. This wire’s from your aunt. She wants me to come up to London at once. Can I borrow your car?”

“Of course.”

“Thanks,” said Tuppy, and dashed out. He had been gone only a second when Jeeves came in with the restorative.

“Mr. Glossop’s gone, Jeeves.”

“Indeed, sir?”

“To London.”

“Yes, sir?”

“In my car. To see my cousin Angela. The sun is once more shining, Jeeves.”

“Extremely gratifying, sir.”

I gave him the eye.

“Was it you, Jeeves, who phoned to Miss What’s-her-bally-name about the alleged water spaniel?”

“Yes, sir.”

“I thought as much.”

“Yes, sir?”

“Yes. Jeeves, the moment Mr. Glossop told me that a Mysterious Voice had phoned on the subject of Irish water spaniels, I thought as much. I recognized your touch. I read your motives like an open book. You knew she would come buzzing up.”

“Yes, sir.”

“And you knew how Tuppy would react. If there’s one thing that gives a jousting knight the pip, it is to have his audience walk out on him.”

“Yes, sir.”

“But there’s just one point. What will Mr. Glossop say when he finds my cousin Angela full of beans and not delirious?”

“The point had not escaped me, sir. I took the liberty of ringing Mrs. Travers up on the telephone and explaining the circumstances. All will be in readiness for Mr. Glossop’s arrival.”

“Jeeves, you think of everything.”

“Thank you, sir. In Mr. Glossop’s absence, would you care to drink this whisky-and-soda?”

I shook the head. “No, Jeeves, there is only one man who must do that. It is you. If ever anyone earned a refreshing snort, you are he. Pour it out, Jeeves, and shove it down.”

“Thank you very much, sir.”

“Cheerio, Jeeves!”

“Cheerio, sir, if I may use the expression.”

Notes:

Annotations to this story as it appeared in Very Good, Jeeves are on this site.

Compare the British magazine version in the Strand magazine.

Madame Eulalie’s Rare Plums

Madame Eulalie’s Rare Plums