The Saturday Evening Mail: New York, September 28, 1912.

THE PRINCE

AND BETTY

———————————————————

By Pelhan G. Wodehouse

ILLUSTRATED BY JOHN V. RANCK

SYNOPSIS

===========

BENJAMIN SCOBELL, a wealthy promoter, buys the gambling privilege of the island republic of Mervo, in the Mediterranean, and establishes a second Monte Carlo. But the venture does not prosper, and the American decides that he must have some unique method of advertising it. He finds that a descendant of the last Prince of Mervo, who was turned out by the republicans, is living in the United States. He realizes that the presence of a real-for-sure prince would be just the touch needed to make the resort popular with wealthy society. He finds the “prince” in the person of John Maude, of New York, who has recently left college and started a business career in the office of his uncle. Scobell sends his secretary to America to search for John Maude, and cables for his niece Betty to come at once to Mervo. In the meantime Maude has lost his position with his uncle for cutting work to go to a baseball game. Crump, the secretary, informs him that he is a prince by right and explains his ancestry. Maude decides that a job as prince is as good as any other job, and accepts. He arrives at Mervo, where the republicans have made way for a return of royal rule for a consideration from Scobell.

CHAPTER V.

CONTINUED.

DURING the early portion of the ride Mr. Scobell was silent and thoughtful. John’s speech had impressed him neither as oratory nor as an index to his frame of mind. He had not interrupted him, because he knew that none of those present could understand what was being said, and that Mr. Crump was to be relied on as an editor. But he had not enjoyed it. He did not take the people of Mervo seriously himself, but in the prince such an attitude struck him as unbecoming. Then he cheered up. After all, John had given evidence of having a certain amount of what he would have called “get-up” in him. For the purposes for which he needed him, a tendency to make light of things was not amiss. It was essentially as a performing prince that he had engaged John. He wanted him to do unusual things, which would make people talk—aeroplaning was one that occurred to him. Perhaps a prince who took a serious view of his position would try to raise the people’s minds and start reforms and generally be a nuisance. John could, at any rate, be relied upon not to do that.

His face cleared.

“Have a good cigar, prince?” he said, cordially, inserting two fingers in his vest pocket.

“Sure, Mike,” said his highness affably.

Breakfast over, Mr. Scobell replaced the remains of his cigar between his lips and turned to business.

“Eh, prince?” he said.

“Yes!”

“I want you, prince,” said Mr. Scobell, “to help boom this place. That’s where you come in.”

“Sure,” said John.

“As to ruling and all that,” continued Mr. Scobell, “there isn’t any to do. The place runs itself. Some guy gave it a shove a thousand years ago, and it’s been rolling along ever since. What I want you to do is the picturesque stunts. Get a yacht and catch rare fishes. Whoop it up. Entertain swell guys when they come here. Have a court—see what I mean?—same as over in England. Go around in aeroplanes and that style of thing. Don’t worry about money. That’ll be all right. You draw your steady hundred thousand a year, and a good chunk more besides, when we begin to get a move on, so the dough proposition doesn’t need to scare you any.”

“Do I, by George!” said John. “It seems to me that I’ve fallen into a pretty soft thing here. There’ll be a joker in the deck somewhere, I guess. There always is in these good things. But I don’t see it yet. You can count me in all right.”

“Good boy,” said Mr. Scobell. “And now you’ll be wanting to get to the palace. I’ll have them bring the automobile round.” The council of state broke up.

HAVING seen John off in the car, the financier proceeded to his sister’s sitting room. Miss Scobell had breakfasted apart that morning, by request, her brother giving her to understand that matters of state, unsuited to the ear of a third party, must be discussed at the meal. She was reading her New York Herald.

“Well,” said Mr. Scobell, “he’s come.”

“Yes, dear?”

“And just the sort I want. Saw the idea of the thing right away, and is ready to go the limit. No nonsense about him.”

“Is he nice looking, Bennie?”

“Sure. All these Mervo princes have been good lookers, I hear, and this one must be near the top of the list. You’ll like him, Marion. All the girls will be crazy about him in a week.”

Miss Scobell turned a page.

“Is he married?” Her brother started.

“Married? I never thought of that. But no, I guess he’s not. He’d have mentioned it. He’s not the sort to hush up a thing like that. I——”

He stopped short. His green eyes gleamed excitedly.

“Marion!” he cried. “Marion!”

“Well, dear?”

“Listen. Gee, this thing is going to be the biggest ever. I gotta new idea. It just came to me. Your saying that put it into my head. Do you know what I’m going to do? I’m going to cable over to Betty to come right along here, and I’m going to have her marry this prince guy. Yes, sir!”

For once Miss Scobell showed signs that her brother’s conversation really interested her. She laid down her paper and stared at him.

“Betty!”

“Sure, Betty. Why not? She’s a pretty girl. Clever, too. The prince’ll be lucky to get such a wife, for all his darned ancestors away back to the flood.”

“But suppose Betty does not like him?”

“Like him? She’s gotta like him. Say, can’t you make your mind soar, or won’t you? Can’t you see that a thing like this has gotta be fixed different from a marriage between—between a ribbon-counter clerk and the girl who takes the money at a twenty-five-cent hash restaurant in Flatbush? This is a royal alliance. Do you suppose that when a European princess is introduced to the prince she’s going to marry, they let her say: ‘Nothing doing. I don’t like the shape of his nose’?”

HE gave a spirited imitation of a European princess objecting to the shape of her selected husband’s nose.

“It isn’t very romantic, Bennie,” sighed Miss Scobell. She was a confirmed reader of the more sentimental class of fiction, and this businesslike treatment of love’s young dream jarred upon her.

“It’s founding a dynasty. Isn’t that romantic enough for you? You make me tired, Marion.”

Miss Scobell sighed again.

“Very well, dear. I suppose you know best. But perhaps the prince won’t like Betty.”

Mr. Scobell gave a snort of disgust.

“Marion,” he said, “you’ve got a mind like a chunk of wet dough. Can’t you understand that the prince is just as much in my employment as the man who scrubs the Casino steps? I’m hiring him to be Prince of Mervo, and his first job as Prince of Mervo will be to marry Betty. I’d like to see him kick!”

He began to pace the room. “By Heck, it’s going to make this place boom to beat the band. It’ll be the biggest kind of advertisement. Restoration of royalty at Mervo. That’ll make them take notice by itself. Then, biff! right on top of that, Royal Romance—Prince Weds American Girl—Love at First Sight—Picturesque Wedding! Gee, we’ll wipe Monte Carlo clean off the map. We’ll have ’em licked to a splinter. We— It’s the greatest scheme on earth.”

“I have no doubt you are right, Bennie,” said Miss Scobell, “but—” her voice became dreamy again—“it’s not very romantic.”

“Oh, shucks!” said the schemer. “Here, where’s a cable form?”

CHAPTER VI.

YOUNG ADAM CUPID.

ON a red sandstone rock at the edge of the water, where the island curved sharply out into the sea, Prince John of Mervo sat and brooded on first causes. For nearly an hour and a half he had been engaged in an earnest attempt to trace to its source the acute fit of depression which had come—apparently from nowhere—to poison his existence that morning.

It was his seventh day on the island, and he could remember every incident of his brief reign. The only thing that eluded him was the recollection of the exact point when the shadow of discontent had begun to spread itself over his mind. Looking back, it seemed to him that he had done nothing during that week but enjoy each new aspect of his position as it was introduced to his notice. Yet here he was, sitting on a lonely rock, consumed with an unquenchable restlessness, a kind of trapped sensation. Exactly when and exactly how Fate, that king of gold-brick men, had cheated him he could not say; but he knew, with a certainty that defied argument, that there had been sharp practice, and that in an unguarded moment he had been induced to part with something of infinite value in exchange for a gilded fraud.

The mystery baffled him. He sent his mind back to the first definite entry of Mervo into the foreground of his life. He had come up from his stateroom on to the deck of the little steamer, and there in the pearl-gray of the morning was the island, gradually taking definite shape as the pink mists shredded away before the rays of the rising sun. As the ship rounded the point where the lighthouse still flashed a needless warning from its cluster of jagged rocks, he had had his first view of the town, nestling at the foot of the hill, gleaming white against the green, with the gold-domed Casino towering in its midst. In all southern Europe there was no view to match it for quiet beauty. For all his thews and sinews there was poetry in John, and the sight had stirred him like wine.

It was not then that depression had begun, nor was it during the reception at the quay.

THE days that had followed had been peaceful and amusing. He could not detect in any one of them a sign of the approaching shadow. They had been lazy days. His duties had been much more simple than he had anticipated. He had not known, before he tried it, that it was possible to be a prince with so small an expenditure of mental energy. As Mr. Scobell had hinted, to all intents and purposes he was a mere ornament. His work began at eleven in the morning, and finished as a rule at about a quarter after. At the hour named a report of the happenings of the previous day was brought to him. When he had read it the state asked no more of him until the next morning.

The report was made up of such items as “A fisherman named Lesieur called Carbineer Ferrier a fool in the market place at eleven minutes after two this afternoon; he has not been arrested, but is being watched,” and generally gave John a few minutes of mild enjoyment. Certainly he could not recollect that it had ever depressed him.

No, it had been something else that had worked the mischief and in another moment the thing stood revealed, beyond all question of doubt. What had unsettled him was that unexpected meeting with Betty Silver last night at the Casino.

He had been sitting at the Dutch table. He generally visited the Casino after dinner. The light and movement of the place interested him. As a rule, he merely strolled through the rooms, watching the play; but last night he had slipped into a vacant seat. He had only just settled himself when he was aware of a girl standing beside him. He got up.

“Would you care—?” he had begun, and then he saw her face.

It had all happened in an instant. Some chord in him, numbed till then, had begun to throb. It was as if he had awakened from a dream, or returned to consciousness after being stunned. There was something in the sight of her, standing there so cool and neat and composed, so typically American, a sort of goddess of America, in the heat and stir of the Casino, that struck him like a blow.

HOW long was it since he had seen her last? Not more than a couple of years. It seemed centuries. It all came back to him. It was during his last winter at Harvard that they had met. A college friend of hers had been the sister of a college friend of his. They had met several times, but he could not recollect having taken any particular notice of her then, beyond recognizing that she was certainly pretty. The world had been full of pretty American girls then. But now——

He looked at her. And, as he looked, he heard America calling to him. Mervo, by the appeal of its novelty, had caused him to forget. But now, quite suddenly, he knew that he was homesick—and it astonished him, the readiness with which he had permitted Mr. Crump to lead him away into bondage. It seemed incredible that he had not foreseen what must happen.

Love comes to some gently, imperceptibly, creeping in as the tide, through unsuspected creeks and inlets, creeps on a sleeping man, until he wakes to find himself surrounded. But to others it comes as a wave, breaking on them, beating them down, whirling them away.

It was so with John. In that instant when their eyes met the miracle must have happened. It seemed to him, as he recalled the scene now, that he had loved her before he had had time to frame his first remark. It amazed him that he could ever have been blind to the fact that he loved her, she was so obviously the only girl in the world.

“You—you don’t remember me,” he stammered. She was flushing a little under his stare, but her eyes were shining.

“I remember you very well, Mr. Maude,” she said with a smile. “I thought I knew your shoulders before you turned round. What are you doing here?”

“I——”

THERE was a hush. The croupier had set the ball rolling. A wizened little man and two ladies of determined aspect were looking up disapprovingly. John realized that he was the only person in the room not silent. It was impossible to tell her the story of the change in his fortunes in the middle of this crowd. He stopped, and the moment passed.

The ball dropped with a rattle. The tension relaxed.

“Won’t you take this seat?” said John.

“No, thank you. I’m not playing. I only just stopped to look on. My aunt is in one of the rooms, and I want to make her come home. I’m tired.”

“Have you——?” He caught the eye of the wizened man, and stopped again.

“Have you been in Mervo long?” he said, as the ball fell.

“I only arrived this morning. It seems lovely. I must explore to-morrow.”

She was beginning to move off.

“Er——” John coughed to remove what seemed to him a deposit of sawdust and unshelled nuts in his throat. “Er—may I—will you let me show you—” prolonged struggle with the nuts and sawdust; then rapidly—“some of the places to-morrow?”

HE had hardly spoken the words when it was borne in upon him that he was a vulgar, pushing bounder, presuming on a dead and buried acquaintanceship to force his company on a girl who naturally did not want it, and who would now proceed to snub him as he deserved. He quailed. Though he had not had time to collect and examine and label his feelings, he was sufficiently in touch with them to know that a snub from her would be the most terrible thing that could possibly happen to him.

She did not snub him. Indeed, if he had been in a state of mind coherent enough to allow him to observe, he might have detected in her eyes and her voice signs of pleasure.

“I should like it very much,” she said.

John made his big effort. He attacked the nuts and sawdust which had come back and settled down again in company with a large lump of some unidentified material, as if he were bucking center. They broke before him as, long ago, the Yale line had done, and his voice rang out as if through a megaphone, to the unconcealed disgust of the neighboring gamesters.

“If you go along the path at the foot of the hill,” he bellowed rapidly, “and follow it down to the sea, you get a little bay full of red sandstone rocks—you can’t miss it—and there’s a fine view of the island from there. I’d like awfully well to show that to you. It’s great.”

She nodded.

“Then shall we meet there?” she said. “When?”

John was in no mood to postpone the event.

“As early as ever you like,” he roared.

“At about ten, then. Good night, Mr. Maude.”

JOHN had reached the bay at half-past eight, and had been on guard there ever since. It was now past ten, but still there were no signs of Betty. His depression increased. He told himself that she had forgotten. Then, that she had remembered, but had changed her mind. Then, that she had never meant to come at all. He could not decide which of the three theories was the most distressing.

His mood became morbidly introspective. He was weighed down by a sense of his own unworthiness. He submitted himself to a thorough examination, and the conclusion to which he came was that, as an aspirant to the regard of a girl like Betty he did not score a single point. No wonder she had ignored the appointment.

A cold sweat broke out on him. This was the snub! She had not administered it in the Casino simply in order that, by being delayed, its force might be the more overwhelming.

He looked at his watch again, and the world grew black. It was twelve minutes after ten.

JOHN, in his time, had thought and read a good deal about love. Ever since he had grown up, he had wanted to fall in love. He had imagined love as a perpetual exhilaration, something that flooded life with a golden glow as if by the pressing of a button or the pulling of a switch, and automatically removed from it everything mean and hard and uncomfortable; a something that made a man feel grand and god-like, looking down (benevolently, of course) on his fellow men as from some lofty mountain.

That it should make him feel a worm-like humility had not entered his calculations. He was beginning to see something of the possibilities of love. His tentative excursions into the unknown emotion, while at college, had never really deceived him; even at the time a sort of second self had looked on and sneered at the poor imitation.

This was different. This had nothing to do with moonlight and soft music. It was raw and hard. It hurt. It was a thing sharp and jagged, tearing at the roots of his soul.

He turned his head, and looked up the path for the hundredth time, and this time he sprang to his feet. Between the pines on the hillside his eye had caught the flutter of a white dress.

CHAPTER VII.

MR. SCOBELL IS FRANK.

MUCH may happen in these rapid times in the course of an hour and a half. While John was keeping his vigil on the sandstone rock, Betty was having an interview with Mr. Scobell which was to produce far-reaching results, and which, incidentally, was to leave her angrier and more at war with the whole of her world than she could remember to have been in the entire course of her life.

The interview began shortly after breakfast in a gentle and tactful manner, with Aunt Marion at the helm. But Mr. Scobell was not the man to stand by silently while persons were being tactful. At the end of the second minute he had plunged through his sister’s mild monologue like a rhinoceros through a cobweb, and had stated definitely, with an economy of words, the exact part which Betty was to play in Mervian affairs.

“You say you want to know why you were cabled for. I’ll tell you. There’s no use talking for half a day before you get to the point. I guess you’ve heard that there’s a prince here instead of a republic now? Well, that’s where you come in.”

“Do you mean——?” she hesitated.

“Yes, I do,” said Mr. Scobell. There was a touch of doggedness in his voice. He was not going to stand any nonsense, by Heck, but there was no doubt that Betty’s wide-open eyes were not very easy to meet. He went on rapidly. “Cut out any fool notions about romance.” Miss Scobell, who was knitting a sock, checked her needles for a moment in order to sigh. Her brother eyed her morosely, then resumed his remarks. “This is a matter of state. That’s it. You gotta cut out fool notions and act for good of state. You gotta look at it in the proper spirit. Great honor—see what I mean? Princess and all that. Chance of a lifetime—dynasty—you gotta look at it that way.”

Miss Scobell heaved another sigh, and dropped a stitch.

“For the love of Mike,” said her brother, irritably, “don’t snort like that, Marion.”

“Very well, dear.”

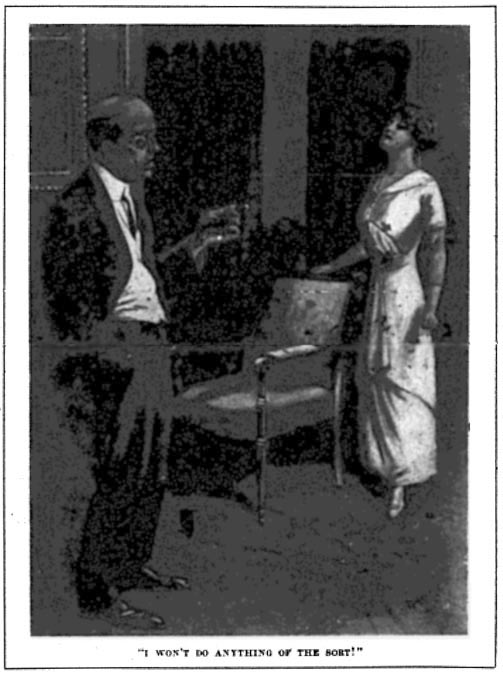

BETTY had not taken her eyes off him from his first word. An unbiased observer would have said that she made a pretty picture, standing there, in her white dress, but in the matter of pictures, still life was evidently what Mr. Scobell preferred, for his gaze never wandered from the cigar stump which he had removed from his mouth in order to knock off the ash.

Betty continued to regard him steadfastly. The shock of his words had to some extent numbed her. At this moment she was merely thinking, quite dispassionately, what a singularly nasty little man he looked, and wondering—not for the first time—what strange quality, invisible to everybody else, it had been in him that had made her mother his adoring slave during the whole of their married life.

Then her mind began to work actively once more. She was a western girl, and an insistence on freedom was the first article in her creed. A great rush of anger filled her, that this man should set himself up to dictate to her.

“Do you mean that you want me to marry this prince?” she said.

“That’s right.”

“I won’t do anything of the sort.”

“Pshaw! Don’t be foolish. You make me tired.”

Betty’s eye shone mutinously. Her cheeks were flushed, and her slim, boyish figure quivered. Her chin, always determined, became a silent Declaration of Independence.

“I won’t,” she said.

AUNT MARION, suspending operations on the sock, went on with tact at the point where her brother’s interruption had forced her to leave off.

“I’m sure he’s a very nice young man. I have not seen him, but everybody says so. You like him, Bennie, don’t you?”

“Sure, I like him. He’s a corker. Wait till you see him, Betty. Nobody’s asking you to marry him before lunch. You’ll have plenty of time to get acquainted. It beats me what you’re kicking at. You give me a pain in the neck. Be reasonable.”

Betty sought for arguments to clinch her refusal.

“It’s ridiculous,” she said. “You talk as if you had just to wave your hand. Why should your prince want to marry a girl he has never seen?”

“He will,” said Mr. Scobell confidently.

“How do you know?”

“Because I know he’s a sensible young skeesicks. That’s how. See here, Betty, you’ve gotten hold of wrong ideas about this place. You don’t understand the position of affairs. Your aunt didn’t till I put her wise.”

“He bit my head off, my dear,” murmured Miss Scobell, knitting placidly.

“You’re thinking that Mervo is an ordinary state, and that the prince is one of those independent, all-wool, off-with-his-darned-head rulers like you read about in the best sellers. Well, you’ve got another guess coming. If you want to know who’s the big noise here, it’s me—me! This prince guy is my hired man. See? Who sent for him? I did. Who put him on the throne? I did. Who pays him his salary? I do, from the profits of the Casino. Now do you understand? He knows his job. He knows which side his bread’s buttered. When I tell him about this marriage, do you know what he’ll say? He’ll say ‘Thank you, sir!’ That’s how things are in this island.”

Betty shuddered. Her face was white with humiliation. She half-raised her hands with an impulsive movement to hide it.

“I won’t. I won’t. I won’t!” she gasped.

Printer’s error corrected above:

In Ch. V, newspaper had the question mark after “shape of his nose” inside both single and double closing quotation marks; corrected to match book edition and the sense of the grammar

Madame Eulalie’s Rare Plums

Madame Eulalie’s Rare Plums