The Saturday Evening Mail: New York, December 14, 1912.

THE PRINCEandBETTY

By Pelhan G. Wodehouse

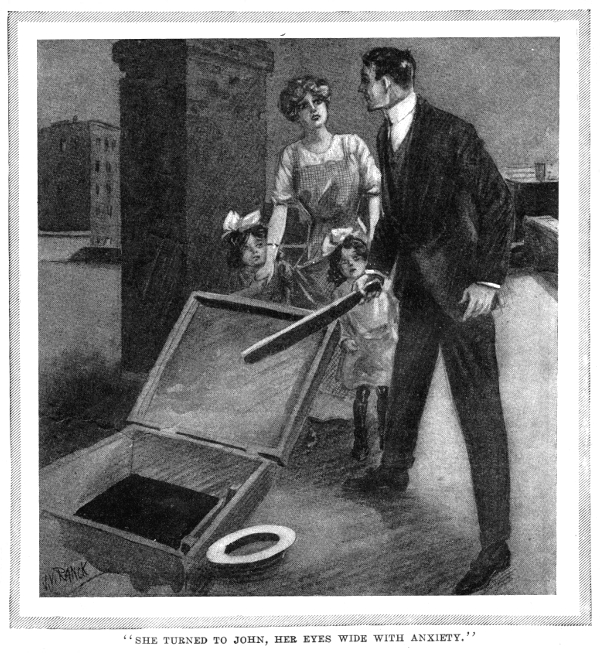

ILLUSTRATED BY JOHN V. RANCK

CHAPTER XXVI.

JOURNEY’S END.

JOHN stood thinking. His mind was working rapidly. Suddenly he smiled. “It’s all right, Pugsy,” he said. “It looks bad, but I see a way out. I’m going up that ladder there and through the trapdoor on to the roof. I shall be all right there. If they find me, they can only get at me one at a time. And, while I’m there, here’s what I want you to do.”

“Shall I go for de cops, boss?”

“No, not the cops. Do you know where Dude Dawson lives?”

The light of intelligence began to shine in Master Maloney’s face. His eye glistened with approval. This was strategy of the right sort.

“I can ask around,” he said. “I’ll soon find him all right.”

“Do, and as quick as you can. And when you’ve found him tell him that his old chum, Spider Reilly, is here, with the rest of his crowd. And now I’d better be getting up on to my perch. Off you go, Pugsy, my son, and don’t take a week about it. Good-by.”

Pugsy vanished, and John, going to the ladder, climbed out on to the roof with his big stick. He looked about him. The examination was satisfactory. The trapdoor appeared to be the only means of access to the roof, and between this roof and that of the next building there was a broad gulf. The position was practically impregnable. Only one thing could undo him, and that was, if the enemy should mount to the next roof and shoot from there. And even then he would have cover in the shape of the chimney. It was a pity that the trap opened downward, for he had no means of securing it and was obliged to allow it to hang open. But, except for that, his position could hardly have been stronger.

As yet there was no sound of the enemy’s approach. Evidently, as Pugsy had said, they were conducting the search, room by room, in a thorough and leisurely way. He listened with his ear close to the open trapdoor, but could hear nothing.

A startled exclamation directly behind him brought him to his feet in a flash, every muscle tense. He whirled his stick above his head as he turned, ready to strike, then let it fall with a clatter. For there, a bare yard away, stood Betty.

THE capacity of the human brain for surprise, like that of the human body for pain, is limited. For a single instant a sense of utter unreality struck John like a physical blow. The world flickered before his eyes, and the air seemed full of strange noises. Then, quite suddenly, these things passed, and he found himself looking at her with a total absence of astonishment, mildly amused in some remote corner of his brain at his own calm. It was absurd, he told himself, that he should be feeling as if he had known of her presence there all the time. Yet it was so. If this were a dream, he could not be taking the miracle more as a matter of course. Joy at the sight of her he felt, keen and almost painful, but no surprise. The shock had stunned his sense of wonder.

She was wearing a calico apron over her dress, an apron that had evidently been designed for a large woman. Swathed in its folds, she suggested a child playing at being grown up. Her sleeves were rolled back to the elbow, and her slim arms dripped with water. Strands of brown hair were blowing loose in the evening breeze. To John she had never seemed so bewitchingly pretty. He stared at her till the pallor of her face gave way to a warm red glow.

As they stood there, speechless, there came from the other side of the chimney, softly at first, then swelling, the sound of a child’s voice, raised in a tentative wail. Betty started violently. The next moment she was gone, and from the unseen parts beyond the chimney came the noise of splashing water.

And at the same instant, through the trap, came a trampling of feet and the sound of whispering. The enemy had reached the top floor.

John was conscious of a remarkable exhilaration. He felt insanely light hearted. He laughed aloud at the thought that until then he had completely forgotten the very existence of these earnest seekers after his downfall. He threw back his head and shouted. There was something so ridiculous in their assumption that they mattered to a man who had found Betty again.

HE thrust his head down through the trap, to see what was going on. The dark passage was full of indistinct forms, gathered together in puzzled groups. The mystery of the vanished object of their pursuit was being discussed in hoarse whispers.

Suddenly there was an excited shout, then a rush of feet. John drew back his head, and waited, gripping his stick.

Voices called to each other in the passage below.

“De roof!”

“On top de roof!”

“He’s beaten it for de roof!”

Feet shuffled on the stone floor. The voices ceased abruptly. And then, like a jack-in-the-box, there popped through the trap a head and shoulders.

The new arrival was a young man with a shock of red hair, a broken nose, and a mouth from which force or the passage of time had removed three front teeth. He held on to the edge of the trap, and stared up at John.

John beamed down at him, and shifted his grip on the stick.

“Who’s here?” he cried. “Historic picture. ‘Old Dr. Cook discovers the North Pole.’ ”

The red-headed young man blinked. The strong light of the open air was trying to his eyes.

“Youse had best come down,” he observed coldly. “We’ve got youse.”

“And,” continued John, unmoved, “is instantly handed a gum-drop by his faithful Eskimo.”

As he spoke, he brought the stick down on the knuckles which disfigured the edges of the trap. The intruder uttered a howl and dropped out of sight. In the passage below there were whisperings and mutterings, growing gradually louder till something resembling coherent conversation came to John’s ears, as he knelt by the trap making meditative billiard shots with the stick at a small pebble.

“Aw g’wan! Don’t be a quitter.”

“Who’s a quitter?”

“Youse a quitter. Get on top de roof. He can’t hoit youse.”

“De guy’s gotten a big stick.”

John nodded appreciatively.

“I and Theodore,” he murmured.

A somewhat baffled silence on the part of the attacking force was followed by further conversation.

“Gee! Some guy’s got to go up.”

Murmur of assent from the audience.

A voice, in inspired tones: “Let Sam do it.”

The suggestion made a hit. There was no doubt about that. It was a success from the start. Quite a little chorus of voices expressed sincere approval of the very happy solution to what had seemed an insoluble problem. John, listening from above, failed to detect in the choir of glad voices one that might belong to Sam himself. Probably gratification had rendered the chosen one dumb.

“Yes, let Sam do it,” cried the unseen chorus. The first speaker, unnecessarily, perhaps—for the motion had been carried almost unanimously—but possibly with the idea of convincing the one member of the party in whose bosom doubts might conceivably be harbored, went on to adduce reasons.

“Sam bein’ a coon,” he argued, “ain’t goin’ to git hoit by no stick. Youse can’t hoit a coon by soakin’ him on de coco, can you, Sam?”

John waited with some interest for the reply, but it did not come. Possibly Sam did not wish to generalize on insufficient experience.

“We can but try,” said John softly, turning the stick round in his fingers.

A REPORT like a cannon sounded in the passage below. It was merely a revolver shot, but in the confined space it was deafening. The bullet sang up into the sky.

“Never hit me,” said John cheerfully.

The noise was succeeded by a shuffling of feet. John grasped his stick more firmly. This was evidently the real attack. The revolver shot had been a mere demonstration of artillery to cover the infantry’s advance.

Sure enough, the next moment a woolly head popped through the opening, and a pair of rolling eyes gleamed up at him.

“Why, Sam!” he said cordially, “this is great. Now for our interesting experiment. My idea is that you can hurt a coon’s head with a stick if you hit it hard enough. Keep quite still. Now. What, are you coming up? Sam, I hate to do it, but——”

A yell rang out. John’s theory had been tested and proved correct.

By this time the affair had begun to attract spectators. The noise of the revolver had proved a fine advertisement. The roof of the house next door began to fill up. Only a few of the occupants could get a clear view of the proceedings, for the chimney intervened. There was considerable speculation as to what was passing in the Three Points’ camp. John was the popular favorite. The early comers had seen his interview with Sam, and were relating it with gusto to their friends. Their attitude toward John was that of a group of men watching a dog at a rat hole. They looked to him to provide entertainment for them but they realized that the first move must be with the attackers. They were fair minded men, and they did not expect John to make any aggressive move.

Their indignation, when the proceedings began to grow slow, was directed entirely at the dilatory Three Pointers. They hooted the Three Pointers. They urged them to go home and tuck themselves up in bed. The spectators were mostly Irishmen, and it offended them to see what should have been a spirited fight so grossly bungled.

“G’wan away home, ye quitters!” roared one.

A second member of the audience alluded to them as “stiffs.”

It was evident that the besieging army was beginning to grow a little unpopular. More action was needed if they were to retain the esteem of Broster street.

Suddenly there came another and a longer explosion from below, and more bullets wasted themselves on air. John sighed.

“You make me tired,” he said.

The Irish neighbors expressed the same sentiment in different and more forcible words. There was no doubt about it—as warriors, the Three Pointers were failing to give satisfaction.

A voice from the passage called to John.

“Say!”

“Well?” said John.

“Are youse comin’ down off out of dat roof?”

“Would you mind repeating that remark?”

“Are youse goin’ to quit off out of dat roof?”

“Go away and learn some grammar,” said John severely.

“Hey!”

“Well?”

“Are youse——?”

“No, my son,” said John, “since you ask it, I am not. I like being up here. How is Sam?”

THERE was silence below. The time began to pass slowly. The Irishmen on the other roof, now definitely abandoning hope of further entertainment, proceeded with hoots of derision to climb down one by one into the recesses of their own house.

And then from the street far below there came a fusillade of shots and a babel of shouts and counter shots. The roof of the house next door filled again with a magical swiftness, and the low wall facing the street became black with the backs of those craning over. There appeared to be great doings in the street.

John smiled comfortably.

In the army of the corridor confusion had arisen. A scout, clattering upstairs, had brought the news of the Table Hillites’ advent, and there was doubt as to the proper course to pursue. Certain voices urged going down to help the main body. Others pointed out that this would mean abandoning the siege of the roof. The scout who had brought the news was eloquent in favor of the first course.

“Gee!” he cried, “don’t I keep tellin’ youse dat de Table Hills is here? Sure, dere’s a whole bunch of dem, and unless youse come on down dey’ll bite de hull head off of us lot. Leave dat stiff on de roof. Let Sam wait here wit’ his canister, and den he can’t get down, ’cos Sam’ll pump him full of lead while he’s beatin’ it t’roo de trapdoor. Sure!”

John nodded reflectively.

“There is certainly something in that,” he murmured. “I guess the grand rescue scene in the third act has sprung a leak. This will want thinking over.”

In the street the disturbance had now become terrible. Both sides were hard at it, and the Irishmen on the roof, rewarded at last for their long vigil, were yelling encouragement promiscuously and whooping with the unfettered ecstasy of men who are getting the treat of their lives without having paid a penny for it.

The behavior of the New York policeman in affairs of this kind is based on principles of the soundest practical wisdom. The unthinking man would rush in and attempt to crush the combat in its earliest and fiercest stages. The New York policeman, knowing the importance of his safety, and the insignificance of the gangman’s, permits the opposing forces to hammer each other into a certain distaste for battle, and then, when both sides have begun to have enough of it, rushes in himself and clubs everything in sight. It is an admirable process in its results, but it is sure rather than swift.

PROCEEDINGS in the affair below had not yet reached the police-interference stage. The noise, what with the shots and yells from the street and the ear-piercing approval of the roof audience, was just working up to a climax.

John rose. He was tired of kneeling by the trap, and there was no likelihood of Sam making another attempt to climb through. He got up and stretched himself.

And then he saw that Betty was standing beside him, holding with each hand a small and—by Broster street standards—uncannily clean child. The children were scared and whimpering, and she stooped to soothe them. Then she turned to John, her eyes wide with anxiety.

“Are you hurt?” she cried. “What has been happening? Are you hurt?”

John’s heart leaped at the anxious break in her voice.

“It’s all right,” he said soothingly. “It’s absolutely all right. Everything’s over.”

As if to give him the lie, the noise in the street swelled to a crescendo of yells and shots.

“What’s that?” cried Betty, starting.

“I fancy,” said John, “the police must be taking a hand. It’s all right. There’s a little trouble down below there between two of the gangs. It won’t last long now.”

“Who were those men?”

“My friends in the passage?” he said lightly. “Those were some of the Three Points gang. We were holding the concluding exercise of a rather lively campaign that’s been——”

Betty leaned weakly against the chimney. There was silence now in the street. Only the distant rumble of an elevated train broke the stillness. She drew her hands from the children’s grasp, and covered her face. As she lowered them again, John saw that the blood had left her cheeks. She was white and shaking. He moved forward impulsively.

“Betty!”

She tottered, reaching blindly for the chimney for support, and without further words he gathered her into his arms as if she had been the child she looked, and held her there, clutching her to him fiercely, kissing the brown hair that brushed against his face, and soothing her with vague murmurings.

Her breath came in broken gasps. She laughed hysterically. “I thought they were killing you—killing you—and I couldn’t leave my babies—they were so frightened, poor little mites—I thought they were killing you.”

“Betty!”

HER arms about his neck tightened their grip convulsively, forcing his head down until his face rested against hers. And so they stood, rigid, while the two children stared with round eyes and whimpered unheeded.

Her grip relaxed. Her hands dropped slowly to her side. She leaned back against the circle of his arms and looked up at him—a strange look, full of a sweet humility.

“I thought I was strong,” she said quietly. “I’m weak—but I don’t care.”

He looked at her with glowing eyes, not understanding, but content that the journey was ended, that she was there, in his arms, speaking to him.

“I always loved you, dear,” she went on. “You knew that, didn’t you? But I thought I was strong enough to give you up for—for a principle—but I was wrong. I can’t do without you—I knew it just now when I saw——” She stopped, and shuddered. “I can’t do without you,” she repeated.

She felt the muscles of his arms quiver, and pressed more closely against them. They were strong arms, protecting arms, restful to lean against at the journey’s end.

CHAPTER XXVII.

A LEMON.

THAT bulwark of Peaceful Moments, Pugsy Maloney, was rather the man of action than the man of tact. Otherwise, when, a moment later, he thrust his head up through the trap, he would have withdrawn delicately, and not split the silence with a raucous “Hey!” which acted on John and Betty like an electric shock.

John glowered at him. Betty was pink, but composed. Pugsy climbed leisurely on to the roof, and surveyed the group.

“Why, hello!” he said, as he saw Betty more closely.

“Well, Pugsy,” said Betty. “How are you?”

John turned in surprise.

“Do you know Pugsy?”

Betty looked at him, puzzled.

“Why, of course I do.”

“Sure,” said Pugsy. “Miss Brown was stenographer on de poiper till she beat it.”

“Miss Brown!”

There was utter bewilderment in John’s face.

“I changed my name when I went to Peaceful Moments.”

“Then are you—did you——?”

“Yes, I wrote those articles. That’s how I happen to be here now. I come down every day and help look after the babies. Poor little souls, there seems to be nobody else here who has time to do it. It’s dreadful. Some of them—you wouldn’t believe—I don’t think they could ever have had a real bath in their lives.”

“Baths is foolishness,” commented Master Maloney austerely, eying the scoured infants with a touch of disfavor.

John was reminded of a second mystery that needed solution.

“How on earth did you get up here, Pugsy?” he asked. “How did you get past Sam?”

“Sam? I didn’t see no Sam. Who’s Sam?”

“One of those fellows. A coon. They left him on guard with a gun, so that I shouldn’t get down.”

“Ah, I met a coon beating it down de stairs. I guess dat was him. I guess he got cold feet.”

“Then there’s nothing to stop us from getting down.”

“Nope. Dat’s right. Dere ain’t a T’ree Pointer wit’in a mile. De cops have been loadin’ dem into de patrol wagon by de dozen.”

John turned to Betty.

“We’ll go and have dinner somewhere. You haven’t begun to explain things yet.”

Betty shook her head with a smile.

“I haven’t got time to go out to dinners,” she said. “I’m a working girl. I’m cashier at Fontelli’s Italian Restaurant. I shall be on duty in another half hour.”

John was aghast.

“You!”

“It’s a very good situation,” said Betty demurely. “Six dollars a week and what I steal. I haven’t stolen anything yet, and I think Mr. Jarvis is a little disappointed in me. But of course I haven’t settled down properly.”

“Jarvis? Bat Jarvis?”

“Yes. He has been very good to me. He got me this place, and has looked after me all the time.”

“I’ll buy him a thousand cats,” said John fervently. “But, Betty, you mustn’t go there any more. You must quit. You——”

“If ‘Peaceful Moments’ would re-engage me?” said Betty.

SHE spoke lightly, but her face was serious. “Dear,” she said quickly, “I can’t be away from you now, while there’s danger. I couldn’t bear it. Will you let me come?” He hesitated.

“You will. You must.” Her manner changed again. “That’s settled, then. Pugsy, I’m coming back to the paper. Are you glad?”

“Sure t’ing,” said Pugsy. “You’re to de good.”

“And now,” she went on, “I must give these babies back to their mothers, and then I’ll come with you.”

She lowered herself through the trap, and John handed the children down to her. Pugsy looked on, smoking a thoughtful cigarette.

John drew a deep breath. Pugsy, removing the cigarette from his mouth, delivered himself of a stately word of praise.

“She’s a boid,” he said.

“Pugsy,” said John, feeling in his pocket and producing a roll of bills, “a dollar a word is our rate for contributions like that.”

JOHN pushed back his chair, slightly stretched out his legs and lighted a cigarette, watching Betty fondly through the smoke. The resources of the Knickerbocker Hotel had proved equal to supplying the staff of “Peaceful Moments” with an excellent dinner, and John had stoutly declined to give or listen to any explanations until the coffee arrived.

“Thousands of promising careers,” he said, “have been ruined by the fatal practice of talking seriously at dinner. But now we might begin.”

Betty looked at him across the table with shining eyes. It was good to be together again.

“My explanations won’t take long,” she said. “I ran away from you. And, when you found me, I ran away again.”

“But I didn’t find you,” objected John. “That was my trouble.”

“But my aunt told you I was at ‘Peaceful Moments!’ ”

“On the contrary, I didn’t even know you had an aunt.”

“Well, she’s not exactly that. She’s my stepfather’s aunt—Mrs. Oakley. I was certain you had gone straight to her, and that she had told you where I was.”

“The Mrs. Oakley? The—er—philanthropist?”

“Don’t laugh at her,” said Betty quickly. “She was so good to me!”

“She passes,” said John decidedly.

“And now,” said Betty, “it’s your turn.”

John lighted another cigarette.

“My story,” he said, “is rather longer. When they threw me out of Mervo——”

“What!”

“I’m afraid you don’t keep abreast of European history,” he said. “Haven’t you heard of the great revolution in Mervo and the overthrow of the dynasty? Bloodless, but invigorating. The populace rose against me as one man—except good old Gen. Poineau. He was for me, and Crump was neutral, but apart from them my subjects were unanimous. There’s a republic again in Mervo now.”

“But why? What had you done?”

“Well, I abolished the gaming table. But, more probably,” he went on quickly, “they saw what a perfect dub I was in every——”

She interrupted him.

“Do you mean to say that, just because of me——?”

“Well,” he said awkwardly, “as a matter of fact what you said did make me think over my position, and, of course, directly I thought over it—oh, well, anyway, I closed down gambling in Mervo, and then——”

“John!”

HE was aware of a small hand creeping round the table under cover of the cloth. He pressed it swiftly, and, looking round, caught the eye of a hovering waiter, who swooped like a respectful hawk.

“Did you want anything, sir?”

“I’ve got it, thanks,” said John.

The waiter moved away.

“Well, directly they had fired me, I came over here. I don’t know what I expected to do. I suppose I thought I might find you by chance. I pretty soon saw how hopeless it was, and it struck me that, if I didn’t get some work to do mighty quick, I shouldn’t be much good to any one except the alienists.”

“Dear!”

The waiter stared, but John’s eyes stopped him in mid-swoop.

“Then I found Smith——”

“Where is Mr. Smith?”

“In prison,” said John with a chuckle.

“In prison!”

“He resisted and assaulted the police. I’ll tell you about it later. Well, Smith told me of the alterations in ‘Peaceful Moments,’ and I saw that it was just the thing for me. And it has occupied my mind quite some. To think of you being the writer of those Broster street articles! You certainly have started something, Betty! Goodness knows where it will end. I hoped to have brought off a coup this afternoon, but the arrival of Sam and his friends just spoiled it.”

“This afternoon? Yes, why were you there? What were you doing?”

“I was interviewing the collector of rents and trying to dig his employer’s name out of him. It was Smith’s idea. Smith’s theory was that the owner of the tenements must have some special private reason for lying low, and that he would employ some special fellow, whom he could trust, as a rent collector. And I’m pretty certain he was right. I cornered the collector, a little, rabbit-faced man named Gooch, and I believe he was on the point of—— What’s the matter?”

Betty’s forehead was wrinkled. Her eyes wore a far-away expression.

“I’m trying to remember something. I seem to know the name, Gooch. And I seem to associate it with a little, rabbit-faced man. And—quick, tell me some more about him. He’s just hovering about on the edge of my memory. Quick! Push him in!”

JOHN threw his mind back to the interview in the dark passage, trying to reconstruct it.

“He’s small,” he said slowly. “His eyes protrude—so do his teeth—He—he—yes, I remember now—he has a curious red mark——”

“On his right cheek,” said Betty triumphantly.

“By Jove!” cried John. “You’ve got him?”

“I remember him perfectly. He was——” She stopped with a little gasp.

“Yes?”

“John, he was one of my stepfather’s secretaries,” she said.

They looked at each other in silence.

“It can’t be,” said John at length.

“It can. It is. He must be. He has scores of interests everywhere. He prides himself on it. It’s the most natural thing.”

John shook his head doubtfully.

“But why all the fuss? Your stepfather isn’t the man to mind public opinion——”

“But don’t you see? It’s as Mr. Smith said. The private reason. It’s as clear as daylight. Naturally he would do anything rather than be found out. Don’t you see? Because of Mrs. Oakley.”

“Because of Mrs. Oakley?”

“You don’t know her as I do. She is a curious mixture. She’s double-natured. You called her the philanthropist just now. Well, she would be one if—if she could bear to part with money. Yes, I know it sounds ridiculous. But it’s so. She is mean about money, but she honestly hates to hear of anybody treating poor people badly. If my stepfather were really the owner of those tenements, and she should find it out, she would have nothing more to do with him. It’s true. I know her.”

The smile passed away from John’s face.

“By George!” he said. “It certainly begins to hang together.”

“I know I’m right.”

“I think you are.”

HE sat meditating for a moment. “Well?” he said at last.

“What do you mean?”

“I mean what are we to do? Do we go on with this?”

“Go on with it? I don’t understand.”

“I mean—well, it has become rather a family matter, you see. Do you feel as—warlike against Mr. Scobell as you did against an unknown lessee?”

Betty’s eyes sparkled.

“I don’t think I should feel any different if—if it was you,” she said. “I’ve been spending days and days in those houses, John, dear, and I’ve seen such utter squalor and misery, where there needn’t be any at all if only the owner would do his duty, and—and——”

She stopped. Her eyes were misty.

“Thumbs down, in fact,” said John, nodding. “I’m with you.”

As he spoke, two men came down the broad staircase into the grill room. Betty’s back was toward them, but John saw them and stared.

“What are you looking at?” asked Betty.

“Will you count ten before looking round?”

“What is it?”

“Your stepfather has just come in.”

“What!”

“He’s sitting at the other side of the room, directly behind you. Count ten!”

But Betty had twisted round in her chair.

“Where? Where?”

“Just where you’re looking. Don’t let him see you.”

“I don’t— Oh!”

“Got him?”

He leaned back in his chair.

“The plot thickens, eh?” he said. “What is Mr. Scobell doing in New York, I wonder, if he has not come to keep an eye on his interests?”

Betty had whipped round again. Her face was white with excitement.

“It’s true,” she whispered. “I was right. Do you see who that is with him? The man?”

“Do you know him? He’s a stranger to me.”

“It’s Mr. Parker,” said Betty.

John drew in his breath sharply.

“Are you sure?”

“Positive.”

JOHN laughed quietly. He thought for a moment, then beckoned to the hovering waiter.

“What are you going to do?” asked Betty.

“Bring me a small lemon,” said John.

“Lemon squash, sir?”

“Not a lemon squash. A plain lemon. The fruit of that name. The common or garden citron, which is sharp to the taste and not pleasant to have handed to one. Also a piece of note paper, a little tissue paper, and an envelope.

“What are you going to do?” asked Betty again.

John beamed.

“Did you ever read the Sherlock Holmes story entitled ‘The Five Orange Pips’? Well, when a man in that story received a mysterious envelope containing five orange pips, it was a sign that he was due to get his. It was all over, as far as he was concerned, except ’phoning for the undertaker. I propose to treat Mr. Scobell better than that. He shall have a whole lemon.”

The waiter returned. John wrapped up the lemon carefully, wrote on the note paper the words, “To B. Scobell, Esq., Property Owner, Broster Street, from Prince John, of ‘Peaceful Moments,’ this gift,” and inclosed it in the envelope.

“Do you see that gentleman at the table by the pillar?” he said. “Give him these. Just say a gentleman sent them.”

The waiter smiled doubtfully. John added a two-dollar bill to the collection in his hand.

“You needn’t give him that,” he said.

The waiter smiled again, but this time not doubtfully.

“And now,” said John, as the messenger ambled off, “perhaps it would be just as well if we retired.”

Editor’s notes:

In the book, Chapter XXVI begins “The capacity of the human brain for surprise,” at the first section break of this episode of the serialization.

The newspaper consistently changes the book’s spelling of “enquire” to “inquire” and “enclose” to “inclose”.

Printer’s errors corrected above:

In Ch. XXVII, newspaper omitted “him” from “I’ll buy him a thousand cats”.

In Ch. XXVII, newspaper had “trying to construct it”; amended to “reconstruct” as in book edition.

Madame Eulalie’s Rare Plums

Madame Eulalie’s Rare Plums